Improving Engagement in Antenatal Health Behavior Programs—Experiences of Women Who Did Not Attend a Healthy Lifestyle Telephone Coaching Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

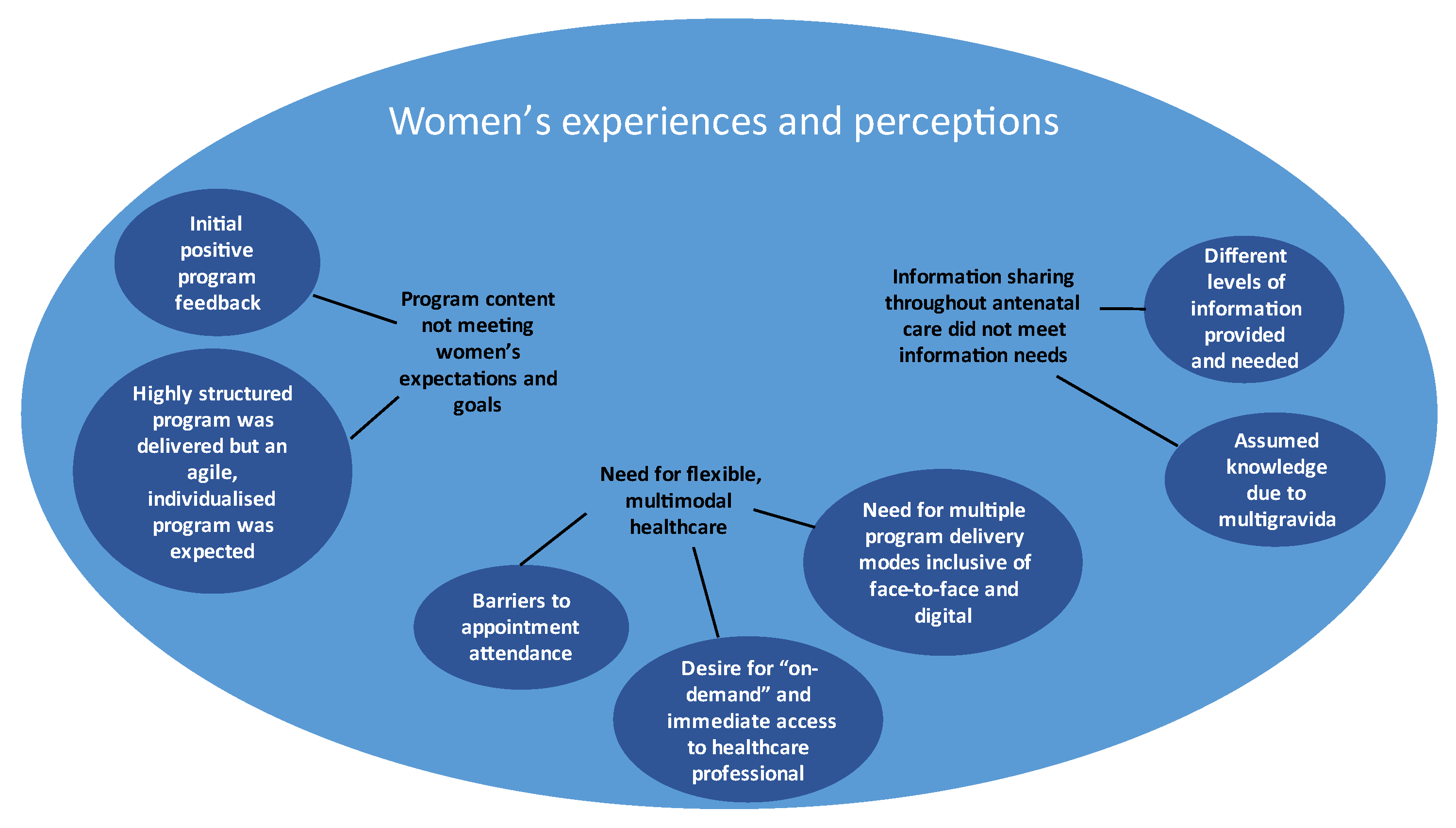

3.1. Part 1: Thematic Analysis

3.1.1. Theme 1: Program Content Not Meeting Women’s Expectations and Goals

- Initial positive program perceptions

“…will help a lot of mums…that like put on weight fast and don’t know why they are…a lot of first-time mums want to know about everything, they want to like search everything up so it’ll be good that they can talk to people… [that] specialize it more than Google”—Participant 6 (Age 22, one appointment attended)

- A highly structured program was delivered but an agile, individualized program was expected

“…I’ll make my goal…to do with exercise like maintaining, say, three sessions a week or something and then she [dietitian] said oh no this week is meant to be about the healthy eating chapter…”—Participant 8 (Age 31, one appointment attended)

“…Going more in depth with concepts for people with higher health literacy…”—Participant 3 (Age 35, one appointment attended)

3.1.2. Theme 2: Need for Flexible, Multimodal Healthcare

- Barriers to appointment attendance

“…it’s really hard to work around…I struggled with work, trying to take time off”—Participant 1 (Age 29, one appointment attended)

“The timetable [for LWdP] doesn’t suit me…it’s quite far for me to come, especially when I got extra three kids with me”—Participant 9 (Age 35, no appointments attended)

- Desire for “on-demand” and immediate access to healthcare professionals

“…[I don’t think] you need to be constantly checked in with every week but you know you can … request appointments or you can have that option of having recurring appointments”—Participant 2 (Age 31, two appointments attended)

“…midwifery program…send a text message … don’t have to wait a week or two weeks to ask a really simple question”—Participant 2 (Age 31, two appointments attended)

- Need for multiple program delivery modes inclusive of face-to-face and digital

“Apps could definitely assist…you can kind of put in your circumstances and it could…come up with…information or areas of concern for you”—Participant 2 (Age 31, two appointments attended)

“…diary entries of what you are eating…it would be a bit easier having it on the phone ‘cause you have your phone on you all the time”—Participant 2 (Age 31, two appointments attended)

3.1.3. Theme 3: Information Sharing throughout Antenatal Care Did Not Meet Information Needs

- Different levels of information provided and needed

“They [midwives] asked me to do just like healthy living style…I put [on] a little bit of weight like during the end of the pregnancy and they said that’s normal, but you can just go on the diet—they give me the booklet and I just eat few of the veggies and…healthy foods…”—Participant 9 (Age 35, no appointments attended)

“I think this booklet have all the information that everyone needed.”—Participant 7 (Age 31, one appointment attended)

“I haven’t really [talked to anyone about healthy eating, exercise or GWG in pregnancy], unless I sought the information out myself…had a look on the internet or I do have a friend who’s a dietitian…”—Participant 8 (Age 31, one appointment attended)

“They [midwives] didn’t tell me much about it [LWdP] because they give me the booklet and they say you can go and refer [to] that”—Participant 9 (Age 35, no appointments attended)

- Assumed knowledge due to multigravida

“I think because this is my second pregnancy, that might like influence the doctor and things”—Participant 8 (Age 31, one appointment attended)

“Not really [needing additional information or support], because this not my first pregnancy…”—Participant 5 (Age 32, one appointment attended)

3.2. Part 2. Deductive Mapping to the TDF, COM-B Model, and BCW

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rasmussen, K.M.; Yaktine, A.L. (Eds.) Institute of Medicine, Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kominiarek, M.A.; Saade, G.; Mele, L.; Bailit, J.; Reddy, U.M.; Wapner, R.J.; Varner, M.W.; Thorp, J.M., Jr.; Caritis, S.N.; Prasad, M.; et al. Association between gestational weight gain and perinatal outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 132, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedderson, M.M.; Gunderson, E.P.; Ferrara, A. Gestational weight gain and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 115, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, R.F.; Abell, S.K.; Ranasinha, S.; Misso, M.L.; Boyle, J.A.; Harrison, C.L.; Black, M.H.; Li, N.; Hu, G.; Corrado, F.; et al. Gestational weight gain across continents and ethnicity: Systematic review and meta-analysis of maternal and infant outcomes in more than one million women. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queensland Health. Queensland Clinical Guidelines, Obesity and Pregnancy (Including Post Bariatric Surgery). 2021. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/142309/g-obesity.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Department of Health, Australian Government, Canberra. Department of Health, Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care. 2020. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/pregnancy-care-guidelines (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gyaenocologists. Management of Obesity in Pregnancy. 2022. Available online: https://ranzcog.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Management-of-Obesity-in-Pregnancy.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Denison, F.C.; Aedla, N.R.; Keag, O.; Hor, K.; Reynolds, R.M.; Milne, A.; Diamond, A. Care of Women with Obesity in Pregnancy. Green-top Guideline No. 72. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 126, e62–e113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.; Pratt, M.; Hutton, B.; Skidmore, B.; Fakhraei, R.; Rybak, N.; Corsi, D.J.; Walker, M.; Velez, M.P.; Smith, G.N.; et al. Guidelines for the management of pregnant women with obesity: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12972. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Weight Management before, during and after Pregnancy (PH27). 2010. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph27 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Wolff, S.; Legarth, J.; Vangsgaard, K.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A. A randomized trial of the effects of dietary counselling on gestational weight gain and glucose metabolism in obese pregnant women. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, A.K.S.; Dietz, P.M.; Galavotti, C.; England, L.J. Weight-management interventions for pregnant or postpartum women. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.A.; Donaldson, E.; Willcox, J. Nutrition and maternal health: A mapping of Australian dietetic services. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.A.; Tolcher, D. Nutrition and maternal health: What women want and can we provide it? Nutr. Diet. 2010, 67, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, J.C.; Campbell, K.J.; van der Pligt, P.; Hoban, E.; Pidd, D.; Wilkinson, S. Excess gestational weight gain: An exploration of midwives’ views and practice. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012, 12, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Pligt, P.; Campbell, K.; Willcox, J.; Opie, J.; Denney-Wilson, E. Opportunities for primary and secondary prevention of excess gestational weight gain: General Practitioners’ perspectives. BMC Fam. Pract. 2011, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, C.; Jimmieson, H.; Ward, N.; Young, A.; de Jersey, S. Poor attendance at group-based interventions for pregnancy weight management-does location and timing matter? Poster 2017, 74, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Jimmieson, H.; Byrne, C.; Ward, N.; Young, A.; de Jersey, S. Poor referral and completion of new dietary intervention targeting high maternal weight and excessive weight gain in pregnancy, does weight play a role? Poster 2017, 74, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Karpavicius, J.; Gasparini, E.; Forster, D. Implementing a diet and exercise program for limiting maternal weight gain in obese pregnant women: A pilot study. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012, 52, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteous, H.; de Jersey, S.; Palmer, M. Attendance rates and characteristics of women with obesity referred to the dietitian for individual weight management advice during pregnancy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 60, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farzandipour, M.; Nabovati, E.; Anvari, S.; Vahedpoor, Z.; Sharif, R. Phone-based interventions to control gestational weight gain: A systematic review on features and effects. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2020, 45, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdijkink, S.B.; Velu, A.V.; Rosman, A.N.; van Beukering, M.D.; Kok, M.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P. The usability and effectiveness of mobile health technology-based lifestyle and medical intervention apps supporting health care during pregnancy: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Smith, P.; Yee, L.M. Mobile phone-based behavioral interventions in pregnancy to promote maternal and fetal health in high-income countries: Systematic review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e15111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, L.; Braeken, M.; Bogaerts, A. Effect of lifestyle coaching including telemonitoring and telecoaching on gestational weight gain and postnatal weight loss: A systematic review. Telemed. J. Ehealth 2019, 25, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherifali, D.; Nerenberg, K.A.; Wilson, S.; Semeniuk, K.; Ali, M.U.; Redman, L.M.; Adamo, K.B. The effectiveness of eHealth technologies on weight management in pregnant and postpartum women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, A.; Smith, A.D.; Chadwick, P.; Croker, H.; Llewellyn, C.H. Exclusively digital health interventions targeting diet, physical activity, and weight gain in pregnant women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2020, 8, e18255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jersey, S.; Meloncelli, N.; Guthrie, T.; Powlesland, H.; Callaway, L.; Chang, A.T.; Wilkinson, S.; Comans, T.; Eakin, E. Implementation of the Living Well During Pregnancy telecoaching program for women at high risk of excessive gestational weight gain: Protocol for an effectiveness-implementation hybrid study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2021, 10, e27196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eakin, E.G.; Hayes, S.C.; Haas, M.R.; Reeves, M.M.; Vardy, J.L.; Boyle, F.; Hiller, J.E.; Mishra, G.D.; Goode, A.D.; Jefford, M.; et al. Healthy Living after Cancer: A dissemination and implementation study evaluating a telephone-delivered healthy lifestyle program for cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra. 2013. Available online: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/files/the_guidelines/n55_australian_dietary_guidelines.pdf: (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Brown, W.J.; Hayman, M.; Haakstad, L.A.H.; Mielke, G.I.; Mena, G.P.; Lamerton, T.; Green, A.; Keating, S.E.; Gomes, G.A.O.; Coombes, J.S. Evidence-Based Physical Activity Guidelines for Pregnant Women; Report for the Australian Government Department of Health; Australian Government Department of Health: Canberra, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Jersey, S.; Meloncelli, N.; Guthrie, T.; Powlesland, H.; Callaway, L.; Chang, A.T.; Wilkinson, S.; Comans, T.; Eakin, E. Outcomes from a hybrid implementation-effectiveness study of the living well during pregnancy Tele-coaching program for women at high risk of excessive gestational weight gain. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiCicco-Bloom, B.; Crabtree, B.F. The qualitative research interview. Med. Educ. 2006, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, K.M.; McDermott, F.; Meadows, G.N. Being pragmatic about healthcare complexity: Our experiences applying complexity theory and pragmatism to health services research. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelan, S. Pregnancy: A “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 202, 135.e1–135.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, C.W.; Leow, S.H.; Ong, L.S.; Erwin, C.; Ong, I.; Ng, X.W.; Tan, J.J.X.; Yap, F.; Chan, J.K.Y.; Loy, S.L. Developing a lifestyle intervention program for overweight or obese preconception, pregnant and postpartum women using qualitative methods. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olander, E.K.; Atkinson, L.; Edmunds, J.K.; French, D.P. Promoting healthy eating in pregnancy: What kind of support services do women say they want? Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2012, 13, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, L.; Olander, E.K.; French, D.P. Why don’t many obese pregnant and post-natal women engage with a weight management service? J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2013, 31, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffery, C.; Lebow-Skelley, E.; Haardoerfer, R.; Boing, E.; Udelson, H.; Wood, R.; Hartman, M.; Fernandez, M.E.; Mullen, P.D. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.K.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Bernhardt, J.M. Mobile text messaging for health: A systematic review of reviews. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2015, 36, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Abraham, C.; Greaves, C.; Yates, T. Self-directed interventions to promote weight loss: A systematic review of reviews. J. Med. Internet Res. 2014, 16, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; D’Agostino, M.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Alkmim, M.B.M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. The impact of mHealth interventions: Systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, M.; Saunders, R.P.; Lattimore, D. The tug-of-war: Fidelity versus adaptation throughout the health promotion program life cycle. J. Prim. Prev. 2013, 34, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Small, S.; Cooney, S.M. Program Fidelity and Adaptation: Meeting Local Needs without Compromising Program Effectiveness. In What Works Wisconsin–Research to Practice Series; University of Wisconsin-Madison/Extension: Madison, WI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ. Behav. 2004, 31, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khomami, M.B.; Walker, R.; Kilpatrick, M.; de Jersey, S.; Skouteris, H.; Moran, L.J. The role of midwives and obstetrical nurses in the promotion of healthy lifestyle during pregnancy. Ther. Adv. Reprod. Health 2021, 15, 26334941211031866. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, C.; Atkinson, L.; Olander, E.K. An exploration of obese pregnant women’s views of being referred by their midwife to a weight management service. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2013, 4, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arden, M.A.; Duxbury, A.M.S.; Soltani, H. Responses to gestational weight management guidance: A thematic analysis of comments made by women in online parenting forums. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, L.; Bould, K.; Aspin-Wood, B.; Sinclair, L.; Ikramullah, Z.; Abayomi, J. The lived experiences of women exploring a healthy lifestyle, gestational weight gain and physical activity throughout pregnancy. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadouch, R.; Hall, C.; Mont, J.D.; D’Souza, R. Obesity in pregnancy–Patient-reported outcomes in qualitative research: A systematic review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2022, 42, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abayomi, J.; Charnley, M.; McCann, M.; Cassidy, L.; Newson, L. The importance of patient and public involvement (PPI) in the design and delivery of maternal weight management advice. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willcox, J.C.; Campbell, K.J.; McCarthy, E.A.; Lappas, M.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Shub, A.; Wilkinson, S.A. Gestational weight gain information: Seeking and sources among pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.D.; Patel, M.S. Designing nudges for success in health care. AMA J. Ethics 2020, 22, E796–E801. [Google Scholar]

- Shea, S.; DuMouchel, W.; Bahamonde, L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 1996, 3, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexheimer, J.W.; Talbot, T.R.; Sanders, D.L.; Rosenbloom, S.T.; Aronsky, D. Prompting clinicians about preventive care measures: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2008, 15, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.; Schoo, A. Supporting self-management of chronic health conditions: Common approaches. Patient Educ. Couns. 2010, 80, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Median (Range)/Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 31 (22–35) |

| Highest Level of Education Year 12 or equivalent Associate or undergraduate diploma Bachelor’s degree (including honors) or higher | 2 (22) 2 (22) 5 (56) |

| Average Household Income $50,000–99,999 $100,000–149,999 $150,000 and above | 3 (33) 2 (22) 4 (45) |

| Country of Birth Australia Other English-speaking country Other non-English speaking country | 5 (56) 3 (33) 1 (11) |

| Primary Language Spoken at Home Arabic English Hindi Igbo | 1 (11) 6 (67) 1 (11) 1 (11) |

| Gravida 1 2 3 4 | 2 (22) 3 (33) 3 (33) 1 (11) |

| Parity 1 2 3 4 | 5 (56) 1 (11) 2 (22) 1 (11) |

| Program Appointments Attended 0 1 2 | 2 (22) 6 (67) 1 (11) |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) | Source of Behavior (COM-B) | Interventions (BCW) | Behavior-Change Techniques | Potential Changes to LWdP and Wider Antenatal Services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Program content not meeting women’s expectations and goals | 1.1 Initial positive program perceptions | Knowledge (E) | Psychological Capacity | Education | Feedback on the behavior/ outcome(s) of the behavior Biofeedback Self-monitoring of behavior/ outcome of behavior Cue-signaling reward Satiation Prompts/cues Information about antecedents Re-attribution Behavioral experiments Information about social and environmental consequences Information about health consequences Information about emotional consequences Information about others’ approval | Updating LWdP advertising material and welcome letter to include risks of excess GWG and benefits of participating in the LWdP program and having a healthy lifestyle during pregnancy. Expanding the pre-program survey to include: - women’s goals and expectations of the program - current knowledge and skills related to healthy eating, physical activity, and GWG In the first program call: - provide feedback about current eating and exercise behaviors from the pre-program survey and current weight-gain trajectory (if wanted by the patient); - Develop SMART goals based on current behavior feedback, tracking tools, and positive self-talk activities with women; - discuss risks of excess GWG and benefits of healthy lifestyles during pregnancy. Embed self-talk practices into the program. Conduct goal-setting and behavior-change activities with women. Add information about these activities and their benefits to the program manual. Re-visit and collaboratively modify goals if needed with women at the beginning of each phone call. When providing information to women about healthy eating, physical activity, and GWG in pregnancy, always discuss the positives and negatives of their behavior on the pregnancy outcomes and the patient’s and child’s health. Education and training of program dietitians to: - utilize women’s goals, expectations, and existing knowledge and skills to tailor the program progression and information shared; - educate and promote positive self-talk with women. Use social support such as regular peer supervision, including discussing complex cases, use of motivational interviewing, reviewing recorded calls, peer shadowing, etc. |

| Optimism (E) | Reflective motivation | Education Modeling | As above AND Use of opinion leaders Feedback Pros and cons Incentive (outcome) Reward (outcome) Self-talk | |||

| 1.2 Highly structured program was delivered but an agile, individualized program was expected | Knowledge (B/E) | Psychological Capacity | Education | As above | ||

| Skills (cognitive/interpersonal) (B/E) | Training | Instruction on how to perform a behavior Behavioral practice/ rehearsal Graded tasks | ||||

| Beliefs about capabilities (B/E) | Reflective motivation | Enablement | Social support (unspecified) Social support (practical) Social support (emotional) Reduce negative emotions Conserve mental resources Pharmacological support Self-monitoring of behavior/ outcome of behavior Behavior substitution Overcorrection Generalization of a target behavior Graded tasks Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behavior Adding objects to the environment Restructuring the physical environment Restructuring the social environment Distraction Body changes Behavioral experiments Mental rehearsal of successful performance Focus on past success Self-talk Verbal persuasion about capability Self-reward Goal setting (behavior) Goal setting (outcome) Behavioral contract Commitment Action planning Review behavior goal(s) Review outcome goal(s) Discrepancy between current behavior and goal Problem solving Pros and cons Comparative imagining of future outcomes Valued self-identity Framing/reframing Incompatible beliefs Identity associated with changed behavior Identification of self as role model Salience of consequences Monitoring of emotional consequences Anticipated regret Imaginary punishment Imaginary reward Vicarious consequences | |||

| 2. Need for flexible, multimodal healthcare | 2.1 Barriers to appointment attendance | Social Influences (B) | Social Opportunity | Environmental restructuring | Cue-signaling reward Remove access to the reward Remove aversive stimulus Satiation Exposure Associative learning Reduce prompt/cue Prompts/cue Adding objects to the environment Restructuring the physical environment Restructuring the social environment | Expand the use of digital health to improve program accessibility, e.g., telehealth, email, text messages. Primary points of contact = telephone, telehealth, email. Multiple modes used across a single program. Use digital resources, e.g., videos, websites, downloadable content, digital intake, and weight trackers. Update the promotion of the program to include the multiple available delivery modes and on-demand services. Modify the program and content to be delivered via multiple modes. Train program staff to use alternative program delivery modes, including on-demand services. Modify clinical workloads to allow for the provision of on-demand access to health professionals through email and/or text messages. Use of change champions and social support to upskill, assist, model, and troubleshoot the use of digital technology. Problem solving such as developing “how to” resources for the use of digital technology |

| 2.2 Desire for “on-demand” and immediate access to healthcare professionals | Environmental context and resources (B/E) | Physical Opportunity | Environmental restructuring Training Enablement | As above | ||

| Social/professional role and identity | Reflective motivation | Education Modeling Persuasion | As above AND Feedback on the behavior Feedback on the outcome(s) of the behavior Biofeedback Re-attribution Focus on past success Verbal persuasion about capability Persuasive source Framing/reframing Identity associated with changed behavior Identification of self as role model Information about social and environmental consequences Information about health consequences Information about emotional consequences Salience of consequences Information about others’ approval Social comparison | |||

| Beliefs about capabilities (B/E) | ||||||

| 2.3 Need for multiple program delivery modes inclusive of face-to-face and digital | Environmental context and resources (B/E) | Physical Opportunity | Environmental restructuring Training | As above | ||

| Social Influences (B) | Social Opportunity | Environmental restructuring | As above | |||

| Beliefs about capabilities (B/E) | Reflective motivation | Education Enablement | As above | |||

| 3. Information sharing throughout antenatal care did not meet information needs | 3.1 Different levels of information provided and needed | Knowledge (B/E) | Psychological Capacity | Education | As above | Ongoing support, education, and training of all HCPs involved in antenatal care to support: - conversations with all patients about healthy eating, exercise, and GWG during pregnancy; - asking patients what information they want about healthy eating, exercise, and GWG during pregnancy; - where and how additional support can be accessed with dedicated resources (physical and digital); Advertisements and information leaflets in maternity clinic rooms and waiting areas that encourage: - discussions about healthy eating, exercise, and GWG in pregnancy; - visual modeling of healthy eating and exercise behaviors in pregnancy; - (self)referral to additional programs and support if needed; - Dietitians and program staff modeling and having discussions with women about healthy eating, exercise, and GWG during pregnancy. |

| Environmental context and resources (B) | Physical Opportunity | Training Environmental restructuring Enablement | As above | |||

| Social/professional role and identity (B/E) | Reflective motivation | Education Training Modeling | As above | |||

| Beliefs about consequences (E) | Persuasion Modeling | As above | ||||

| 3.2 Assumed knowledge due to multigravida | Knowledge (B/E) | Psychological Capacity | Education | As above | ||

| Social/professional role and identity (B/E) | Reflective motivation | Education Training Modeling | As above | |||

| Beliefs about consequences (E) | Persuasion Modeling | As above |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fry, J.; Wilkinson, S.A.; Willcox, J.; Henny, M.; McGuire, L.; Guthrie, T.M.; Meloncelli, N.; de Jersey, S. Improving Engagement in Antenatal Health Behavior Programs—Experiences of Women Who Did Not Attend a Healthy Lifestyle Telephone Coaching Program. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081860

Fry J, Wilkinson SA, Willcox J, Henny M, McGuire L, Guthrie TM, Meloncelli N, de Jersey S. Improving Engagement in Antenatal Health Behavior Programs—Experiences of Women Who Did Not Attend a Healthy Lifestyle Telephone Coaching Program. Nutrients. 2023; 15(8):1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081860

Chicago/Turabian StyleFry, Jessica, Shelley A. Wilkinson, Jane Willcox, Michaela Henny, Lisa McGuire, Taylor M. Guthrie, Nina Meloncelli, and Susan de Jersey. 2023. "Improving Engagement in Antenatal Health Behavior Programs—Experiences of Women Who Did Not Attend a Healthy Lifestyle Telephone Coaching Program" Nutrients 15, no. 8: 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081860

APA StyleFry, J., Wilkinson, S. A., Willcox, J., Henny, M., McGuire, L., Guthrie, T. M., Meloncelli, N., & de Jersey, S. (2023). Improving Engagement in Antenatal Health Behavior Programs—Experiences of Women Who Did Not Attend a Healthy Lifestyle Telephone Coaching Program. Nutrients, 15(8), 1860. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15081860