Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Metabolic Rate and Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Quality Appraisal Strategy

3. Results

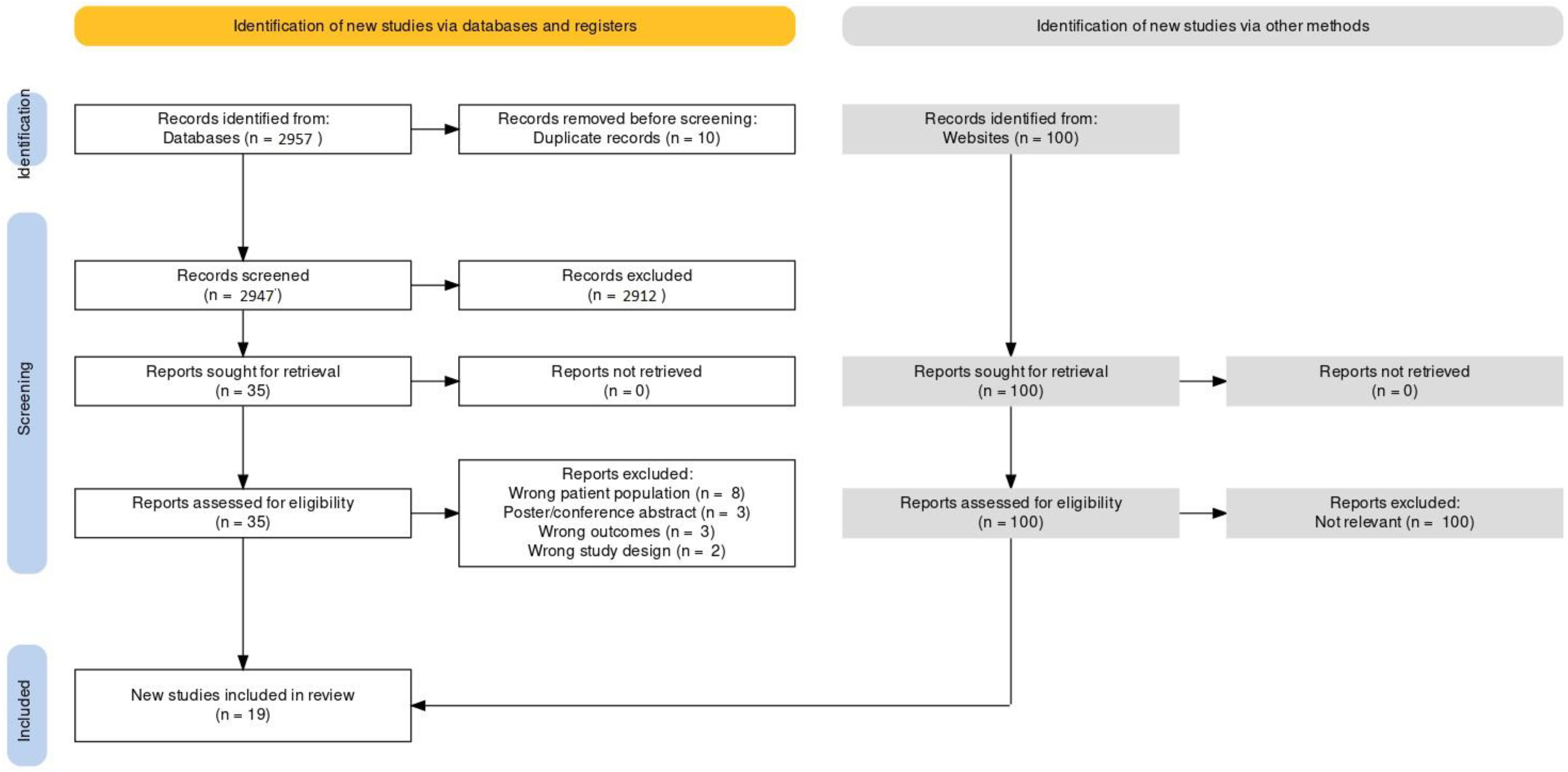

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Quality Appraisal Results

3.3. Characteristics and Findings of Included Studies

3.3.1. Resting Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric versus Control Participants

3.3.2. Predictive Equations versus Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Energy Expenditure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Risk Factor Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Stu. Lancet 2018, 392, 1923–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, R.B.; Brietzke, E.; McIntyre, R.S. Is there a “metabolic-mood syndrome”? A review of the relationship between obesity and mood disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 52, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; Mitchell, A.J.; De Hert, M.; Wampers, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Correll, C.U. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2015, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.K.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.; Ceban, F.; Vinberg, M.; Kessing, L.V.; Ho, R.C.; Rhee, T.G.; Gill, H.; Cao, B.; et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, impaired fasting glucose, general obesity, and abdominal obesity in patients with bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 300, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra e Silva, N.D.M.; Lam, M.P.; Soares, C.N.; Munoz, D.P.; Milev, R.; de Felice, F.G. Insulin resistance as a shared pathogenic mechanism between depression and type 2 diabetes. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.B. Contribution of anaerobic energy expenditure to whole body thermogenesis. Nutr. Metab. 2005, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.D.; Ramachandran, R.; Venkatesan, P.; Anoop, S.; Joseph, M.; Thomas, N. Indirect calorimetry: From bench to bedside. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 21, 594–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães-Ferreira, L. Role of the phosphocreatine system on energetic homeostasis in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Einstein 2014, 12, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrannini, E. The Theoretical Bases of Indirect Calorimetry: A Review. Metabolism 1988, 37, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Hall, M.E. Energetics and Metabolic Rate. In Guytan and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeller, D.A. Energy expenditure from doubly labeled water: Some fundamental considerations in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1983, 38, 999–1005. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/38/6/999/4691119 (accessed on 18 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeller, D.A.; Ravussin, E.; Schutz, Y.; Acheson, K.J.; Baertschi, P.; Jequier, E. Energy expenditure by doubly labelled water: Validation in humans and proposed calculation. Am. J. Physiol. 1986, 250, 823–830. [Google Scholar]

- Ainslie, P.N.; Reilly, T.; Westerterp, K.R. Estimating Human Energy Expenditure: A Review of Techniques with Particular Reference to Doubly Labelled Water. Sport. Med. 2003, 33, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péronnet, F.; Massicotte, D. Table of nonprotein respiratory quotient: An update. Can. J. Sport Sci. 1991, 16, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, J.B.V. New methods for calculating metabolic rate with special reference to protein metabolism. J. Physiol. 1949, 109, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, H.; Helle, S.; Heck, H. The Validity of the Telemetric System CORTEX X I in the Ventilatory and Gas Exchange Measurement during Exercise. Int. J. Sport. Med. 1997, 18, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.; Georg, T.; Becker, C.; Kindermann, W. Reliability of gas exchange measurements from two different spiroergometry systems. Int. J. Sport. Med. 2001, 22, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Lange, S.M.M. Metabolic syndrome in psychiatric patients: Overview, mechanisms, and implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 20, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Non-Randomized Studies in Meta-Analysis. Ottawa Hosp. 2004. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2019, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliyurt, O.; Altiay, G. Resting energy expenditure in manic episode. Bipolar. Disord. 2009, 11, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Anderson, E.J.; Copeland, P.M.; Borba, C.P.; Nguyen, D.D.; Freudenreich, O.; Goff, D.C.; Henderson, D.C. Higher fasting serum insulin is associated with increased resting energy expenditure in nondiabetic schizophrenia patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 60, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet-Michaliszyn, S.B.; Soreca, I.; Otto, A.D.; Jakicic, J.M.; Fagiolini, A.; Kupfer, D.J.; Goodpaster, B.H. A Prospective Observational Study of Obesity, Body Composition, and Insulin Resistance in 18 Women With Bipolar Disorder and 17 Matched Control Subjects. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 69, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaist, P.A.; Obarzanek, E.; Skwerer, R.G.; Duncan, C.C.; Shultz, P.M.; Rosenthal, N.E. Effects of bright light on resting metabolic rate in patients with seasonal affective disorder and control subjects. Biol. Psychiatry 1990, 28, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, K.A.; Perkins, D.O.; Edwards, L.J.; Barrier, R.C.; Lieberman, J.A.; Harp, J.B. Effect of olanzapine on body composition and energy expenditure in adults with first-episode psychosis. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gewirtz, G.R.; Malaspina, D.; Hatterer, J.A.; Feureisen, S.; Klein, D.; Gorman, J.M. Occult thyroid dysfunction in patients with refractory depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 1988, 145, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassapidou, M.; Papadimitriou, K.; Athanasiadou, N.; Tokmakidou, V.; Pagkalos, I.; Vlahavas, G.; Tsofliou, F. Changes in body weight, body composition and cardiovascular risk factors after long-term nutritional intervention in patients with severe mental illness: An observational study. BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, R.; Obarzanek, E.; Mikalauskas, K.M.; Post, R.M.; Jimerson, D.C. The effects of carbamazepine on resting metabolic rate and thyroid function in depressed patients. Biol. Psychiatry 1991, 29, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miniati, M.; Calugi, S.; Simoncini, M.; Ciberti, A.; Girogio Mariani, M.; Mauri, M.; Dell’Osso, L. Resting energy expenditure in a cohort of female patients with bipolar disorder: Indirect calorimetry vs. Harris-Benedict, Mifflin-St. Jeor, LARN Equations. J. Psychopathol. 2015, 21, 119–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, B.M.; Forslund, A.H.; Olsson, R.M.; Hambraeus, L.; Wiesel, F. Differences in resting energy expenditure and body composition between patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 114, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Yi, K.K.; Kim, M.S.; Hong, J.P. Effects of ziprasidone and olanzapine on body composition and metabolic parameters: An open-label comparative pilot study. Behav. Brain Funct. 2013, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, J.K.; Stedman, T.J.; Byrne, N.M.; Wishart, C.; Hills, A.P. Energy expenditure and physical activity in clozapine use: Implications for weight management. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, J.K.; Byrne, N.M.; Stedman, T.J.; Hills, A.P. Resting energy expenditure is lower than predicted in people taking atypical antipsychotic medication. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharpe, J.K.; Stedman, T.J.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P. Low-fat oxidation may be a factor in obesity among men with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2009, 119, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skouroliakou, M.; Giannopoulou, I.; Kostara, C.; Vasilopoulou, M. Comparison of predictive equations for resting metabolic rate in obese psychiatric patients taking olanzapine. Nutrition 2009, 25, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soreca, I.; Mauri, M.; Castrogiovanni, S.; Simoncini, M.; Cassano, G.B. Measured and expected resting energy expenditure in patients with bipolar disorder on maintenance treatment. Bipolar. Disord. 2007, 9, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugawara, N.; Yasui-Furukori, N.; Tomita, T.; Furukori, H.; Kubo, K.; Nakagami, T.; Kaneko, S. Comparison of predictive equations for resting energy expenditure among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, M.; Rissanen, A.; Franssila-Kallunki, A.; Tiihonen, J. Low non-oxidative glucose metabolism and violent offending: An 8-year prospective follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 168, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virkkunen, M.; Rissanen, A.; Naukkarinen, H.; Franssila-Kallunki, A.; Linnoila, M.; Tiihonen, J. Energy substrate metabolism among habitually violent alcoholic offenders having antisocial personality disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 150, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, F.; Riglin, L.; Lomax, T.; Souter, E.; Potter, R.; Smith, D.J.; Thapar, A.K.; Thapar, A. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 243, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansur, R.B.; Lee, Y.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Cha, D.S.; Brietzke, E.; McIntyre, R.S. Parsing metabolic heterogeneity in mood disorders: A hypothesis-driven cluster analysis of glucose and insulin abnormalities. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 22, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millan, M.J. Serotonin 5-HT2C Receptors as a Target for the Treatment of Depressive and Anxious States: Focus on Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Therapies 2005, 60, 441–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, G.P.; Kirk, S.L. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic drug treatment–pharmacological mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 125, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Case-Control Studies | |||||||||

| Author (Year) | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | ||||||

| Caliyurt (2009) [24] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 0/3 | ||||||

| Nilsson (2006) [33] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| Virkkunen (2007) [42] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| Soreca (2007) [39] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| Fleet-Michaliszyn (2008) [26] | 3/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| Sharpe (2009) [37] | 4/4 | 2/2 | 2/3 | ||||||

| Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies—Interventional | |||||||||

| Author (Year) | Confounding Bias | Selection Bias | Classification Bias | Deviation Bias | Missing Data Bias | Measurement Bias | Reporting Bias | Overall Bias | |

| Hassapidou (2011) [30] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Virkkunen (2009) [41] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | |

| Gaist (1990) [27] | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Moderate | |

| Gewirtz (1988) [29] | Serious | Low | Low | Low | Low | Moderate | Low | Serious | |

| Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies | |||||||||

| Author (Year) | Domain 1 | Domain 2 | Domain 3 | Domain 4 | Domain 5 | Domain 6 | Domain 7 | Domain 8 | Overall Appraisal |

| Fan (2006) [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Graham (2005) [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Miniati (2015) [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Sharpe (2005) [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Sharpe (2006) [35] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Skouroliakou (2009) [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Sugawara (2014) [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Herman (1991) [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Include |

| Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2) | |||||||||

| Author (year) | Randomization Process | Deviations from Intended Interventions | Missing Outcome Data | Measurement of the Outcome | Selection of the Reported Result | Overall Bias | |||

| Park (2013) [34] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | |||

| Author (year) | Country | Type of Study/ Design | N | Mean Age in Years (SD) | Population | Intervention (Formulation, Dose, Regimen) | Concomitant Medications (N) | Neuropsychiatric Assessments | Calorimetry Method Used | Main Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caliyurt (2009) [24] | Turkey | Observational/case control | 69 (42 BD-I; 27 HC) | 36.45 (11.23) | BD-I and HCs | No intervention | BD group only: Lithium (24), Chlorpromazine (17), Olanzapine (16), Valproic acid (13), Clonazepam (4), Quetiapine (4), Risperidone (3), Clozapine (1), Carbamazepine (1), Sulpiride (1), Oxcarbazepine (1) | BRMAS | REE was measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Subjects rested in the supine position for 30 min before a 20 min measurement was taken. ‘Steady state’ was determined by device software as 5 min where average O2 changed by less than 10% and RER changed by less than 5%. REE was determined based on an abbreviated Weir equation. | REE was higher in the BD-I group vs. controls. Controls showed significant correlations between BMI and REE that were not replicated in the BD-I group. There was also no relation between BRMAS scores and REE values in BD-I patients. |

| Fan (2006) [25] | United States | Observational/cross sectional | 71 | 42.2 (10.5) | Outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, without diabetes or other significant medical illnesses | No intervention | Clozapine (24), olanzapine (22), risperidone (16), quetiapine (4), ziprasidone (2), medication free (3) | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Subjects were rested with a canopy placed over their head for the collection of expiratory gases. REE was calculated using a standard equation involving the measured RER. | REE measured using the metabolic cart significantly correlated with REE predictions derived from all four equations that were analyzed (Harris–Benedict adjusted and current body weights, Schofield, and Mifflin–St. Jeor) (p < 0.001). The Mifflin–St. Jeor equation correlated most strongly with the metabolic cart measurements, whereas the Harris–Benedict current body weight and Schofield equations significantly overestimated REE (p < 0.001) in SMI patients taking olanzapine. |

| Fleet-Michaliszyn (2008) [26] | United States | Observational/case control | 35 (18 BD-I; 17 HCs) | BD-I = 41.4 (2.1); HCs = 40.9 (2.3) | Women with BD-I, euthymic and treated with ≤3 medications, who never received olanzapine and/or clozapine; and HCs | No intervention | Antipsychotic medications (12; aripiprazole, ziprasidone, haloperidol, quetiapine, or perphenazine), lithium and anticonvulsant medications (17; valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, gabapentin, or topiramate), SSRIs (5; escitalopram, fluoxetine, or sertraline), SNRI (2; venlafaxine), and benzodiazepines (3; lorazepam or clonazepam). Two control subjects (1 obese and 1 normal weight) were treated with antihypertensive agents. | None | REE and substrate oxidation were measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Subjects were rested with an open canopy system placed over their head for the collection of respiratory gases. Measurements were collected for 35 min with the first 5 min of data discarded. Data were obtained at 30 s intervals. Substrate oxidation was determined using a standard equation and TEE and AEE were estimated using an armband that was worn for 5 days. | BD-I patients and healthy controls had comparable insulin resistances (mean ± SEM HOMA-IR = 2.7 ± 0.7 vs. 2.5 ± 0.7, for patients and controls, respectively; p = 0.79). BD-I patients had 13% lower fat oxidation at rest than HCs, but resting metabolic rates were comparable. Activity monitors revealed that neither mean total daily energy expenditure, nor energy expenditure during PA was different between patients and controls. There were also no differences in mean time spent in sedentary, moderate, or vigorous activity. |

| Gaist (1990) [27] | United States | Interventional/Non-randomized experimental study | 19 (10 SAD, 9 HCs) | SAD = 39.1 (5.8); HCs = 38.9 (8.9) | Patients meeting the lifetime criteria for seasonal affective disorder who were drug free for at least a month and scored at least 14 on the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Normal controls were recruited through an advertisement in the Washington Post who were screened and evaluated via a telephone questionnaire, clinical interview, physical examination, and routine laboratory tests. | Bright light exposure therapy | Drug-free for at least 1 month | HAMD | REE was measured via gas-exchange IC after an overnight fast. Patients rested for 2 h with lights either dimmed in the off-light condition or on in the on-light condition. IC measurements were conducted in recumbent position and expired gases were collected for 20 min on a breath-by-breath basis. Data were averaged over 60 s intervals and EE was determined by the Weir equation. REE values were expressed using the DuBois formula to enable comparisons based on body size. | Note: the study was conducted between December and March. SAD patients had significantly higher REE in off-light conditions compared to HCs (mean ± SD = 35.7 ± 3.7 and 30.6 ± 4.9 kcal/m2/h, respectively; p < 0.02, df = 17); After light treatment, REE was significantly reduced in SAD patients (35.7 ± 3.7 versus 32.4 ± 6.3 kcal/m2/h; p < 0.05, df = 9), but not HCs (30.6 ± 4.9 and 29.9 ± 3.12 kcal/m2/h off-light and on-light treatment, respectively). Also, patients’ mood improved in the on-light condition, as indicated by the HAMD (19.5 ± 5.4 versus 5.4 ± 3.3; p < 0.001). |

| Gewirtz (1988) [29] | United States | Interventional/Case series | 15 | Range = 24–59 | Women aged 24–59 with depression refractory to outpatient medication | Thyroxine, liothyronine; various doses; daily | Tranylcypromine (Patient 1 only) | Not reported | Metabolic rate was assessed using gas-exchange IC. Subjects were fasted with a canopy placed over their head for the collection of respiratory gases. Patients were monitored for 30 min and measurements were taken once a steady state was achieved. Heat production per day was inferred based on O2 consumption and CO2 production data. | There was 6 out of the 15 patients with evidence of occult hypothyroidism, all of whom responded to thyroid hormone medication and achieved a normal metabolic rate and/or thyroid hormones, with a reduction in depression, except for one who was lost to follow up. The remaining 9 participants were euthyroid, and/or eumetabolic or hypermetabolic and thus thyroid hormone interventions were not initiated. |

| Graham (2005) [28] | United States | Cohort study | 9 | median age = 21.5 years (range = 20.8–27.3) | Adults with DSM-IV diagnosis of brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder, without other active illnesses and with no history of antipsychotic drug therapy | Olanzapine titrated by the treating physician in 2.5 mg increments, with final doses ranging between 2.5–20 mg/day based on clinical response. | Not reported, but the following medications were allowed: lorazepam, clonazepam, zolpidem, benztropine, and propranolol | None | RER and REE were determined via gas exchange IC 2 h postprandial. After resting supine for 30 min, O2 and CO2 were measured at 30 s intervals for 20 min. REE was determined using the Weir equation. | Median increase in body weight was 4.7 kg after ~12 weeks, a significant increase of 7.3% from first observation. Body fat, measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, increased significantly, with a propensity for central fat deposition. Lean body mass and bone mineral content did not change. Absolute 24 h REE and REE normalized to lean body mass did not change with 12 weeks of olanzapine treatment. Baseline resting energy expenditure was not lower in subjects who gained weight. RER increased significantly with olanzapine treatment (~14%) and was positively correlated with change in weight (r = 0.73). Fasting insulin, C-peptide, and triglyceride levels significantly increased, but there were no changes in glucose levels; total, high-density lipoprotein, or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; or leptin levels. Results suggest decreased fatty acid oxidation and a shift toward carbohydrate oxidation, with possible development of insulin resistance. |

| Hassapidou (2011) [30] | Greece | Interventional/Non-randomized experimental study | Enrolled n = 989; Completed n = 145 | 40 (11.7) | Psychiatric patients with severe mental illness. At baseline, all patients were classified as obese (mean bodyweight = 94.9 ± 21.7 kg; mean BMI of 34.3 ± 6.9 kg/m2). | A dietary regimen designed to produce a weekly caloric deficit of 500 kcal, characterized by moderate consumption of carbohydrates (50–55% of total energy per day) and a high fiber content, 15–20% protein and a fat intake of 30–35% of total energy per day. Patients were advised to consume fruits, vegetables, and whole grains daily and to increase their consumption of olive oil. | Maintained stable regimens throughout the study period: antidepressants (297, 30%); antipsychotics (274, 28%); antipsychotics + antidepressants (230, 23%), antipsychotics + antidepressants + other (188, 19%) | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC. Subjects completed an activity questionnaire and an activity factor of 1.3 to 1.5 was multiplied to REE to determine energy requirements. Description of methodology (i.e., preparations and sampling duration) for IC protocol is absent from manuscript. | Progressive statistically significant reductions in mean weight, fat mass, waist circumference, and BMI throughout the duration of monitoring (p < 0.001). The mean final weight loss was 9.7 kg and BMI decreased to 30.7 kg/m2 (p < 0.001). The mean final fat mass loss was 8.0 kg, and the mean final waist circumference reduction was 10.3 cm (p < 0.001) compared to baseline. Significant and continual reductions were observed in fasting plasma glucose, total cholesterol, and triglycerides concentrations throughout the study (p < 0.001). REE decreased significantly in completers at months 3 and 6 compared to baseline (p < 0.001). |

| Herman (1991) [31] | United States | Observational/cross sectional | 11 (6 Female; 5 Male) | 36 (10.7) | Patients diagnosed with DSM-III major affective disorder, medication free and on a low monoamine diet. | Carbamazepine; 200–1400 mg; daily | Medication free for at least 2 weeks | Bunney–Hamburg Global Rating Scale, HAMD | REE was measured via gas exchange IC using a breath-by breath metabolic cart system. Data were acquired over 20 min with the first 5 min discarded. REE was calculated at 1 min intervals using measured O2 and CO2 and a standardized equation. Predicted REE was calculated using the Harris–Benedict equation. | The mean change in REE for all patients was −0.84 kcal/m2/h, a 2.7% decrease which was not significantly different. The analysis was also performed separately for the two groups of patients with and without multiple measurements of REE. There were no significant differences between REE before and during CBZ treatment when the two groups of patients were considered separately. Mean baseline REEs were not correlated with the Bunney–Hamburg rating the day of REE measurement, the average of 7 days prior, or the baseline Hamilton rating. The change in depression, measured by the Bunney–Hamburg or Hamilton rating, was also not correlated with the change in REE on CBZ. CBZ blood levels, dosages, or duration of CBZ treatment were not correlated with the change in REE. Low baseline REEs were significantly associated with high exposure to TCA/MAOIs, as well as being a woman. Baseline REEs were significantly correlated with the amount of time the patient was on TCA/MAOIs 5 years prior to admission. There was no relationship between the amount of time a patient was off TCA/MAOIs and the baseline REE. There was no correlation between baseline REEs and the number of months depressed 5 years prior to admission. After carbamazepine treatment, T4 decreased significantly (7.53 versus 5.74 mc/dL, p < 0.001), whereas REE did not (31.6 versus 30.7 kcal/m2/h). Body weight significantly and positively correlated with baseline REE in men but not women. |

| Miniati (2015) [32] | Italy | Observational/cross sectional | 17 | 37.3 (11.4) | Female outpatients with BD-I as per the DSM-IV. One patient also met the criteria for obsessive compulsive disorder. | No intervention | Atypical antipsychotics: olanzapine (11; dose range 2.5–15 mg/day), quetiapine (3; dose range 25–100 mg/day), aripiprazole (3, dose range 2.5–15 mg/day). Mood stabilizers: lithium (7; dose range 300–900 mg/day), valproate (3; dose range 500–1200 mg/day), oxcarbazepine (1; 300 mg/day), carbamazepine (1; 300 mg/day), pregabalin (1; 225 mg/day). | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Patients were seated during measurement. Description of sampling duration for IC is absent from the manuscript. Measured REE was compared with predictive REE regression equations: Harris–Benedict, LARN, and Mifflin–St. Jeor. | There was a significant positive relationship between REE and fasting serum insulin level (r = 0.39, p = 0.001). Higher fat-free mass and higher fasting serum insulin level predicted increased REE, which could mitigate further weight gain in nondiabetic individuals with schizophrenia. |

| Nilsson (2006) [33] | Sweden | Observational/case control | 47 (30 SCZ; 17 HC) | SCZ = 33.0 (8.7); HCs = 32.3 (7.9) | Physically healthy patients who fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder, and age- and gender-matched controls with no personal or familiar history of psychiatric disorder. | No intervention | Clozapine (9), olanzapine (5), risperidone (3), haloperidol (1), zuclopenthixol (1); non-medicated (11) | PANSS, GAF | Gas exchange IC was performed in the fasted state using an open ventilated metabolic cart device for measurement of O2 and CO2. Participants were resting for a measurement time of 45 min. Gas exchange was collected for 60 s intervals and researchers used last 15 min as resting value. REE was determined according to Weir formula and RER determined from IC device. | REE was significantly lower in the patients than in the controls. A decrease was also seen in the non-medicated patients. The patients showed significantly lower percentages of water in FFM and intracellular water |

| Park (2013) [34] | South Korea | Interventional/RCT | 20 (10 ziprasidone, 10 olanzapine; 50% females in each group) | Ziprasidone = 34.50 (interquartile range [IQR] = 26.25–40.25); Olanzapine = 31.50 (IQR = 26.50–41.25); [p > 0.99] | Adults diagnosed with a brief psychotic disorder, schizophrenia, or related disorders according to the DSM-IV and no other active illnesses, free of antipsychotics for at least 3 months. Anxiolytics were permitted. | Ziprasidone or Olanzapine, started at 40 and 10 mg/day, respectively; mean daily doses during the 12-week study period were 109 (range: 65–140) mg/day for ziprasidone and 11.6 (range: 8.2–15.5) mg/day for olanzapine. | Lorazepam, clonazepam, zolpidem, benztropine, or propranolol were the only drugs permitted | DSM-IV Korean Version, PANSS | RER and REE were determined via gas-exchange IC. O2 and CO2 were measured at 30 s intervals over 20 min and REE was calculated using a standardized equation. | After 12 weeks of treatment, the percent changes in body weight (p = 0.016), BMI (p = 0.019), and waist-to-hip ratio (p = 0.004) were significantly greater in patients treated with olanzapine than with ziprasidone. REE and RER were not affected by olanzapine therapy, while ziprasidone significantly increased REE normalized to lean body mass; however, between-groups differences in the percent or absolute changes in EE measures were not significant. |

| Sharpe (2009) [37] | Australia | Observational/case control | 62 (31 SCZ, 31 HCs) | SCZ = 34.2 (10.1); HCs = 34.6 (10.1) | Men diagnosed with schizophrenia per the DSM-IV on atypical antipsychotics for at least 4 months; and HCs matched for age and weight adjusted for height. Participants having medical conditions with the potential to affect REE or body composition were excluded. | No intervention | All participants with schizophrenia had been taking an atypical antipsychotic medication [clozapine (15), olanzapine (6), risperidone (7), quetiapine (1), aripiprazole (2)] for more than 4 months as their primary antipsychotic medication | PANSS | REE was measured via gas-exchange IC using a ventilated hood system. Subjects were assessed in the rested state after an overnight fast in the supine position. REE was measured after a 10 min adaptation period and was continuously monitored for 30 min. A total of 10 min of steady state data were acquired and REE was calculated using the abbreviated Weir equation. | The SCZ group showed a significantly lower mean REE than HCs (t = −2.08, p = 0.046; 95% CI of difference −178 kcal/day to −2 kcal/day and t = 2.91, p = 0.007; 95% CI of difference 0.02 to 0.09). However, after adjusting for FFM, no significant difference between SCZ and HC groups was observed in REE (F = 0.69, p = 0.41; 95% CI of difference—124 to +52 kcal/day). Fasting RER was significantly higher in the SCZ group compared to HCs after adjusting for FFM (F = 6.12, p = 0.004). |

| Sharpe (2006) [35] | Australia | Observational/cross sectional | 8 | 28.0 (6.7) | Men with schizophrenia prescribed clozapine for at least 6 months | Clozapine (mean daily dose = 456 ± 143 mg; mean duration = 20.5 ± 12.8 months) | Citalopram (2), amisulpride (1), chlorpromazine (1), diazepam (1), paroxetine (1), risperidone (1), sodium valproate (1) and venlafaxine (1) | None | Free-living TEE was measured via DLW method using oral ingestion of 0.05 g kg−1 [2H2O] and 0.15 g kg−1 [H218O]. Urine samples were collected over 10 days. TEE was calculated using multipoint slope–intercept method, with tracer dilution spaces calculated via back extrapolation. REE was measured using gas exchange IC in fasted state. Participants rested for 10 min adaptation before O2 and CO2 were analyzed for 30 min. Steady state defined as 10 min where coefficient of variation of O2 and CO2 was less than 10%. | The TEE was 2511 ± 606 kcal per day which was significantly lower (by 21%) than WHO recommendations. Physical activity levels confirmed the sedentary nature of people with schizophrenia who take clozapine. |

| Sharpe (2005) [36] | Australia | Observational/cross sectional | 8 | 28.0 (6.7) | Men diagnosed with chronic paranoid schizophrenia taking clozapine for >6 months, without medical conditions known to affect REE | Clozapine: Dose = 456 ± 143 mg/day; mean months taking clozapine 20.5 ± 12.8 | Not reported | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC using a ventilated hood system. Participants were tested immediately upon waking up, in the fasted state. ‘Steady state’ was defined as 10 min where the coefficient of variation in O2 and CO2 was less than 10%. | Harris–Benedict and Schofield equations overestimated resting energy expenditure by ~280 kcal/day for patients taking clozapine. Predictions from the other predictive equations were highly variable and deemed not clinically appropriate for REE estimation. |

| Skouroliakou (2008) [38] | Greece | Observational/cross sectional | 128 | 41.19 (11.22) | DSM-IV mood or psychotic disorder patients | No intervention | Olanzapine (all subjects; stable for at least 6 months) | None | REE measurement was performed via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Participants were in the supine position after resting for 10 min. Measurements were conducted for 20 min with the first 5 min of data discarded. ‘Steady state’ data were defined as the 15 min at which the coefficient of variation in O2 and CO2 was less than 10%. | REE measured using the metabolic cart significantly correlated with REE predictions derived from all four equations that were analyzed (Harris–Benedict adjusted and current body weights, Schofield, and Mifflin–St. Jeor) (p < 0.001). The Mifflin–St. Jeor equation correlated most strongly with the metabolic cart measurements, whereas the Harris–Benedict current body weight and Schofield equations significantly overestimated REE (p < 0.001) in SMI patients taking olanzapine. |

| Soreca (2007) [39] | Italy | Observational/case control | 32 (15 BD-I; 17 HCs) | BD-I = 37.13 (range 21–51 years); HCs = 35.59 (range 21–53 years) | Patients with BD-I recruited from the outpatient and day hospital care services at the University of Pisa, in a maintenance treatment phase, taking olanzapine for >6 months. Patients were free from medical comorbidities known to affect REE and weight. HCs were matched for age and gender, with no personal history of mood disorder, and were not on any medication. | The BD-I group was receiving olanzapine, mean dose = 6 mg/day (range 2.5–15 mg/day) | Lithium 600–900 mg/day (6), valproate 500–1000 mg/day (6), paroxetine 20 mg/day (3), sertraline 50–100 mg/day (3), fluoxetine 20 mg/day (1), fluvoxamine 150 mg/day (1), citalopram 20 mg/day (1), venlafaxine 75 mg/day (1) | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Participants rested for 30 min before breathing through a standard mouthpiece for ~10 min of data collection. Device measured O2 only and assumed an RER of 0.85. Measured REE was compared to predictive REE equations: Harris–Benedict (HB), Schofield (S), LARN, and OUR. | Independent samples t-tests showed no significant difference between patients and controls for age and mean measured REE, but mean BMI was significantly greater in the patient group. Paired t-tests showed significant differences between expected REE (HB), REE (S), REE (LARN), REE (OUR), and REE measured with IC in the bipolar group for all the equations, with mean expected REE higher than measured REE. Expected REE (HB), (S), (LARN), (OUR), and measured REE did not differ significantly in the control group. The aforementioned equations systematically overestimated REE in BD-I subjects maintained on olanzapine. |

| Sugawara (2014) [40] | Japan | Observational/cross sectional | 110 | 45.9 (13.2) | DSM-IV schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | No intervention | Antipsychotic combination therapy (73), risperidone (13), aripiprazole (11), olanzapine (6), quetiapine (4), blonanserin (2), perospirone (1) | None | REE was measured via gas exchange IC in the fasted state. Participants rested for 30 min before breathing through a standard mouthpiece for ~10 min of data collection. | Measured and predicted REEs were significantly correlated for all four equations (p < 0.001), with the Harris–Benedict equation demonstrating the strongest correlation in both men and women (r = 0.617, p < 0.001). Bland–Altman analysis revealed that the Harris–Benedict and Mifflin–St Jeor equations did not show a significant bias in the prediction of REE, whereas a significant overestimation error was shown for the FAO/WHO/UNU and Schofield equations. |

| Virkkunen (2009) [41] | Finland | Observational/case control | 89 (49 habitually violent offenders; 40 HC) | Recidivistic offenders: [n = 17; 32.3 (10.7)]; non-recidivistic offenders: [n = 32; 32.9 (9.2)]; HCs: [n = 40; 33.7 (8.7)] | Habitually violent offenders who fulfilled the DSM-III criteria for antisocial personality disorder and alcohol dependence. | No intervention | Drug- and medication-free | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, axes I and II | Gas exchange IC was used to determine glucose oxidation rates in the basal state and after 150 to 180 min of insulin clamp. Participants were in the fasted state and RER was used to infer substrate utilization. No mention in manuscript of sampling window used for IC measurement. | Offenders who committed at least one new violent crime during the 8-year follow-up had a mean NOG of 1.4 standard deviations lower than non-recidivistic offenders. In logistic regression analysis, NOG alone explained 27% of the variation in the recidivistic offending. The recidivistic offenders had higher baseline insulin levels than non-recidivistic offenders and healthy subjects, while IQ scores did not differ between recidivistic and non-recidivistic offenders (F1,44 = 0.93, p = 0.34). |

| Virkkunen (2007) [42] | Finland | Observational/case control | 136 (67 P-APD; 29 F-APD; 40 HC) | P-APD = 33.2 (11.2); F-APD = 39.0 (8.1); HCs = 33.7 (8.7) | Male habitually violent offenders admitted from prison, fulfilling DSM-III-R criteria for persistent antisocial personality disorder (P-APD), in addition to previously incarcerated offenders (F-APD) and healthy male controls matched for age and weight | No intervention | All participants were drug free for at least 7 days prior to calorimetry | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R, axes I and II | Gas exchange IC was used to measure O2 and CO2 in the basal state and at 150 to 180 min of insulin clamp. Participants were in the fasted state and RER was used to infer substrate utilization. No mention in manuscript of sampling window used for IC measurement. | Habitually violent, incarcerated offenders with APD had significantly lower non-oxidative glucose metabolism, basal glucagon, and free fatty acids when compared with normal controls, but glucose oxidation and CSF 5-HIAA did not differ markedly between these groups. The effect sizes for lower non-oxidative glucose metabolism among incarcerated and non-incarcerated APD subjects were 0.73 and 0.51, respectively, when compared with controls, indicating that this finding was not explained by incarceration. Habitually violent offenders with APD have markedly lower glucagon and non-oxidative glucose metabolism when compared with healthy controls, and these findings were more strongly associated with habitual violent offending than low CSF 5-HIAA levels. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Vincenzo, J.D.; O’Brien, L.; Jacobs, I.; Jawad, M.Y.; Ceban, F.; Meshkat, S.; Gill, H.; Tabassum, A.; Phan, L.; Badulescu, S.; et al. Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Metabolic Rate and Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071686

Di Vincenzo JD, O’Brien L, Jacobs I, Jawad MY, Ceban F, Meshkat S, Gill H, Tabassum A, Phan L, Badulescu S, et al. Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Metabolic Rate and Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(7):1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071686

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Vincenzo, Joshua Daniel, Liam O’Brien, Ira Jacobs, Muhammad Youshay Jawad, Felicia Ceban, Shakila Meshkat, Hartej Gill, Aniqa Tabassum, Lee Phan, Sebastian Badulescu, and et al. 2023. "Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Metabolic Rate and Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review" Nutrients 15, no. 7: 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071686

APA StyleDi Vincenzo, J. D., O’Brien, L., Jacobs, I., Jawad, M. Y., Ceban, F., Meshkat, S., Gill, H., Tabassum, A., Phan, L., Badulescu, S., Rosenblat, J. D., McIntyre, R. S., & Mansur, R. B. (2023). Indirect Calorimetry to Measure Metabolic Rate and Energy Expenditure in Psychiatric Populations: A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 15(7), 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15071686