Sodium Content in Pre-Packaged Foods in China: A Food Label Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

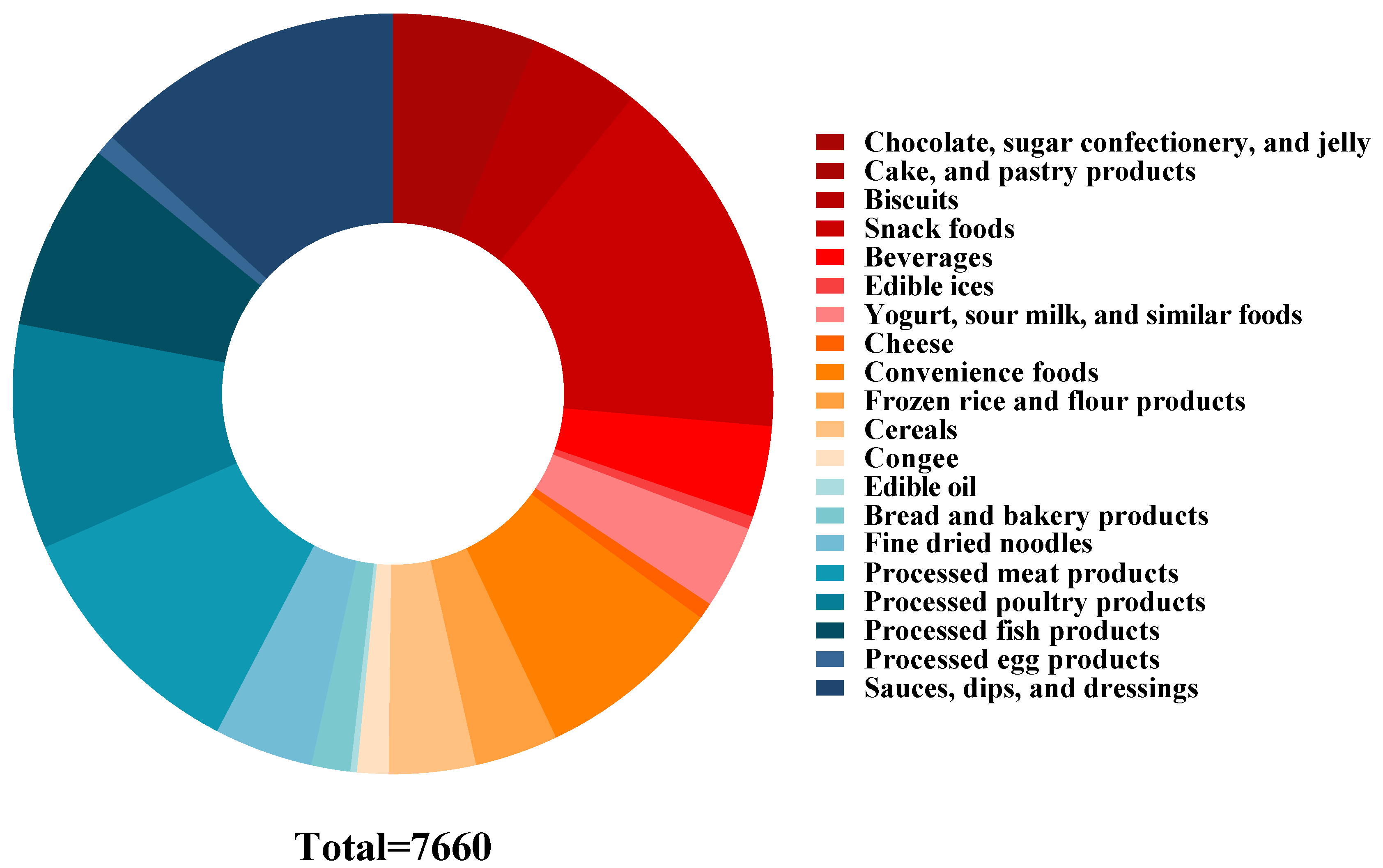

2.1. Data Collection for Chinese Pre-Packaged Foods

2.2. Data Classification

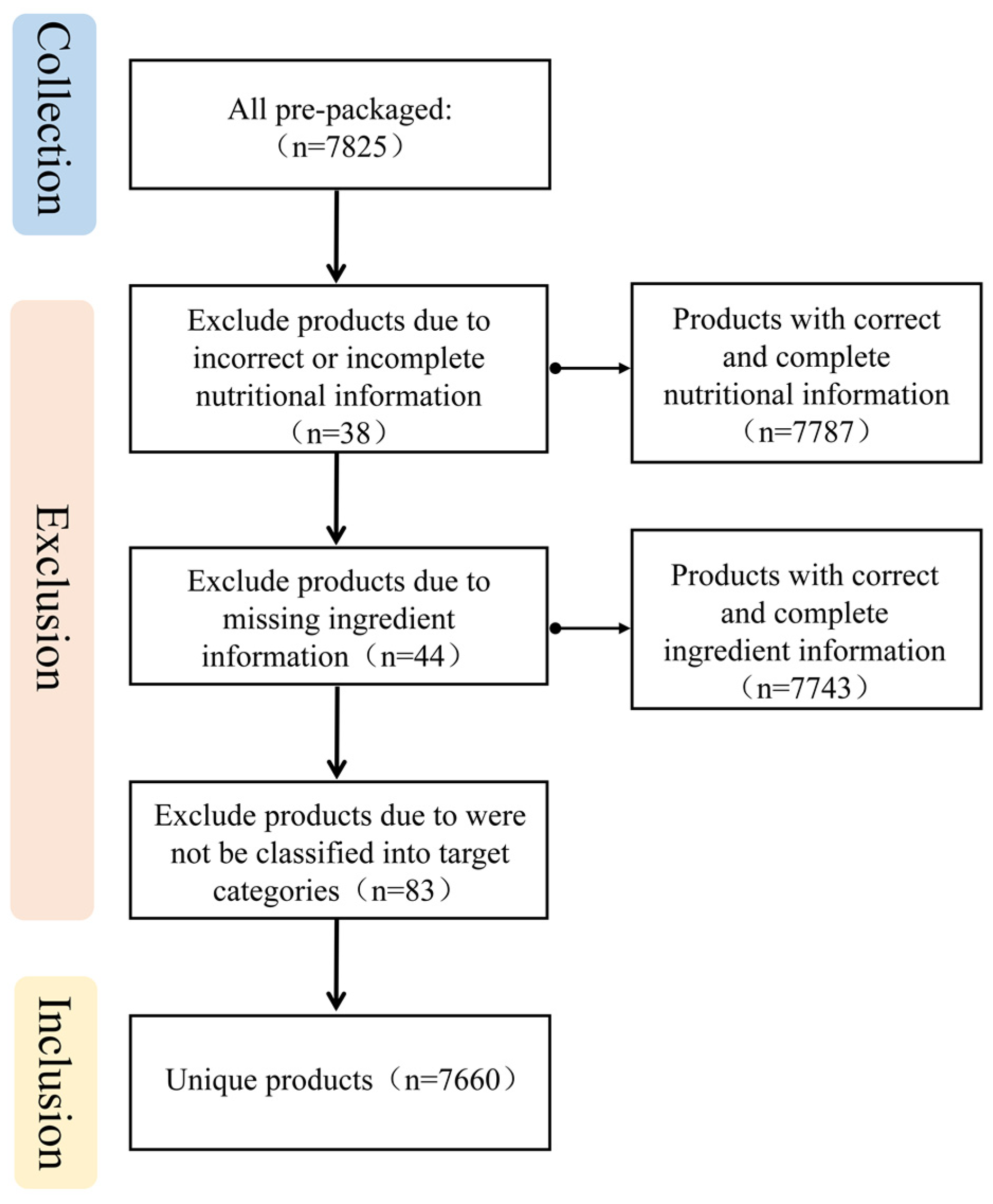

2.3. Data Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Sodium Content for Chinese Pre-Packaged Foods

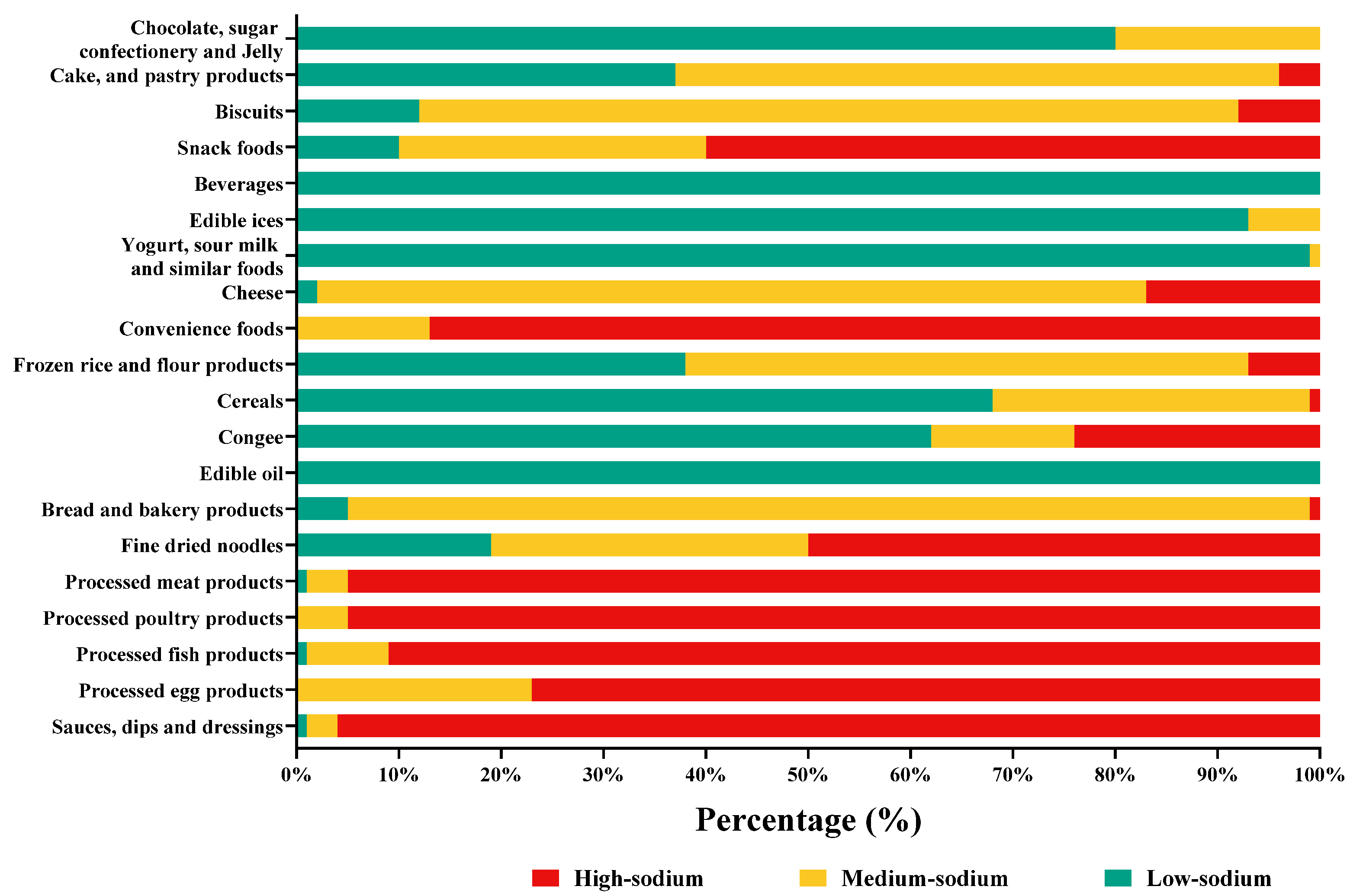

3.2. Proportion of Chinese Pre-Packaged Foods Meeting Low-Sodium, Medium-Sodium, and High-Sodium Content

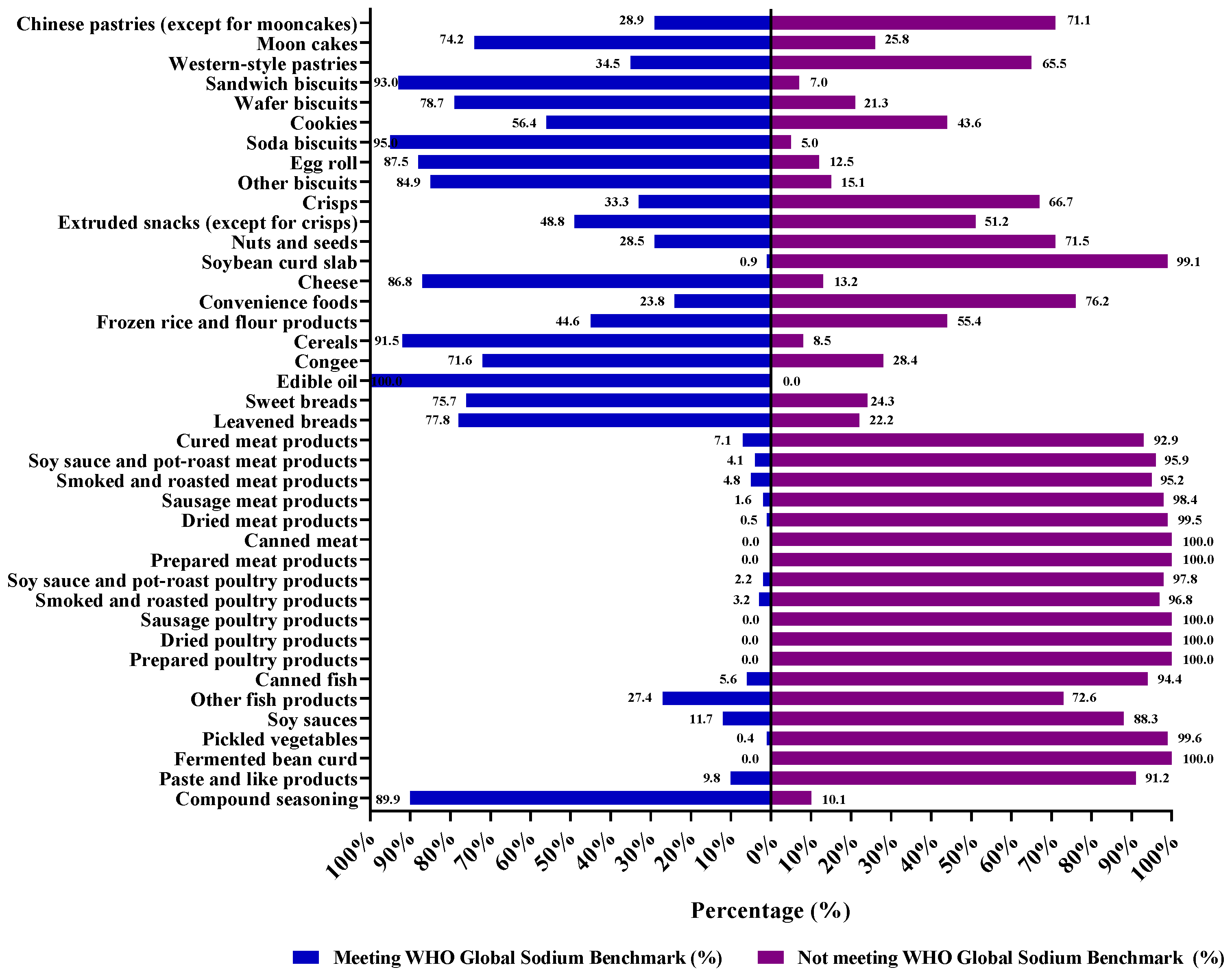

3.3. The Median Sodium Content of Chinese Pre-Packaged Foods Meeting and Not Meeting WHO Global Sodium Benchmarks

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Filippini, T.; Malavolti, M.; Whelton, P.K.; Naska, A.; Orsini, N.; Vinceti, M. Blood Pressure Effects of Sodium Reduction: Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies. Circulation 2021, 143, 1542–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Trieu, K.; Yoshimura, S.; Neal, B.; Woodward, M.; Campbell, N.; Li, Q.; Lackland, D.T.; Leung, A.A.; Anderson, C.; et al. Effect of dose and duration of reduction in dietary sodium on blood pressure levels: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br. Med. J. 2020, 368, m315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Fahimi, S.; Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Engell, R.E.; Lim, S.; Danaei, G.; Ezzati, M.; Powles, J. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Lu, X.; Li, J. Different Changing Patterns for Stroke Subtype Mortality Attributable to High Sodium Intake in China During 1990 to 2019. Stroke 2023, 54, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund International; American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Stomach Cancer; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Messerli, F.H.; Hofstetter, L.; Syrogiannouli, L.; Rexhaj, E.; Siontis, G.; Seiler, C.; Bangalore, S. Sodium intake, life expectancy, and all-cause mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2103–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Sodium Intake Reduction; Report No.: 9789240069985 (Electronic Version); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sodium Intake for Adults and Children; Report No.: 9789241504836; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Nutrition Society. Dietary Guidelines for Chinese (2022); People’s Medical Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Du, S.; Su, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H.; Popkin, B.M. The food retail revolution in China and its association with diet and health. Food Policy 2015, 55, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Du, W.; Huang, F.; Jiang, H.; Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Twenty-Five-Year Trends in Dietary Patterns among Chinese Adults from 1991 to 2015. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Tackling NCDs: ‘Best Buys’ and Other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. The SHAKE Technical Package for Salt Reduction; Report No.: 9789241511346; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.A.; Tekle, D.; Rosewarne, E.; Flexner, N.; Cobb, L.; Al-Jawaldeh, A.; Kim, W.J.; Breda, J.; Whiting, S.; Campbell, N.; et al. A Systematic Review of Salt Reduction Initiatives Around the World: A Midterm Evaluation of Progress Towards the 2025 Global Non-Communicable Diseases Salt Reduction Target. Adv. Nutr. 2021, 12, 1768–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; Brinsden, H.C.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: A successful experiment in public health. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2014, 28, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musicus, A.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Bleich, S.N. Policy Progress in Reducing Sodium in the American Diet, 2010–2019. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2020, 40, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.T.; Hack, S.; Jessri, M.; Arcand, J.; McLaren, L.; L’Abbé, M.R.; Anderson, L.N.; Hobin, E.; Hammond, D.; Manson, H.; et al. The Equity and Effectiveness of Achieving Canada’s Voluntary Sodium Reduction Guidance Targets: A Modelling Study Using the 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition. Nutrients 2021, 13, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndanuko, R.N.; Shahid, M.; Jones, A.; Harris, T.; Maboreke, J.; Walker, A.; Raubenheimer, D.; Simpson, S.J.; Neal, B.; Wu, J.H.; et al. Projected effects on salt purchases following implementation of a national salt reduction policy in South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4614–4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund; Pan American Health Organization. Etiquetado Nutricional en la Parte Frontal del Envase en América Latina y el Caribe; Nota Orientadora; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Mapping Dietary Salt/Sodium Reduction Policies and Initiatives in the Region of the Americas; Report No.: 978-92-75-12324-9 (Print); PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GB 28050-2011; General Rules for Nutrition Labeling of Prepackaged Foods. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Yang, Y.X.; Gao, C.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.Y.; Lai, J.Q.; Ding, G.G. Introduction to Guidelines for Salt Reduction in Chinese Food Industry. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2019, 53, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- GB 2760-2014; National Food Safety Standard Standard for Uses of Food Additives. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2014.

- WS/T 464-2015; Regulation of Food Composition Data Expression. China Standard Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Sodium Benchmarks for Different Food Categories; Report No.: 9789240025097 (Electronic Version); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Yin, P.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 394, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Murray, C. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Hemler, E.C.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; He, L.; et al. The dietary transition and its association with cardiometabolic mortality among Chinese adults, 1982–2012: A cross-sectional population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019, 7, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcand, J.; Blanco-Metzler, A.; Benavides, A.K.; L’Abbe, M.R.; Legetic, B. Sodium Levels in Packaged Foods Sold in 14 Latin American and Caribbean Countries: A Food Label Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, K.; Rådholm, K.; Dunford, E.; Wu, J.; Neal, B.; Sundström, J. Sodium content in processed food items in Sweden compared to other countries: A cross-sectional multinational study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1182132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.; Waqa, G.; Pillay, A.; Kama, A.; Tukana, I.N.; McKenzie, B.L.; Webster, J.; Johnson, C. Packaged food supply in Fiji: Nutrient levels, compliance with sodium targets and adherence to labelling regulations. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4358–4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Du, W.; Huang, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B. Dietary Sodium Intake of Adult Residents in 15 Provinces of China. Food Nutr. China 2022, 28, 75–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; He, F.J.; Ding, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; MacGregor, G.A. Salt content of sauces in the UK and China: Cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e25623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, F.; Zhai, F.; Zhang, B. Investigation on the Consumption KAP of Pre-packagedFood Among Urban Residents in China. Food Nutr. China 2015, 21, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, P.; Popkin, B.M.; Coyle, D.H.; Ding, J.; Dong, L.; Zhang, J.; Du, W.; Pettigrew, S. Nutritional Quality of Pre-Packaged Foods in China under Various Nutrient Profile Models. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Tan, M.; He, F.J.; Harris, T.; MacGregor, G.A.; Ding, J.; et al. Cross-sectional comparisons of sodium content in processed meat and fish products among five countries: Potential for feasible targets and reformulation. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e46412. [Google Scholar]

- Farrand, C.; Charlton, K.; Crino, M.; Santos, J.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, R.; Ni, M.C.; Webster, J. Know Your Noodles! Assessing Variations in Sodium Content of Instant Noodles across Countries. Nutrients 2017, 9, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Dong, L.; He, F.J.; Brown, M.; Pettigrew, S.; Webster, J.; Yamamoto, R.; Nishida, C.; et al. Sodium content targets for pre-packaged foods, China: A quantitative study and proposal. Bull. World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunteman, A.N.; McKenzie, E.N.; Yang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Lee, S.Y. Compendium of sodium reduction strategies in foods: A scoping review. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1300–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, D.; Strazzullo, P.; Serafini, M.; Porrini, M.; Pellegrini, N.; Angelino, D. Sodium Content in Cereal-Based Products Sold in Italy: How Far Are We from the Global Benchmarks? Nutrients 2022, 14, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.J.; MacGregor, G.A. A comprehensive review on salt and health and current experience of worldwide salt reduction programmes. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2009, 23, 363–384. [Google Scholar]

- Pietinen, P.; Mannisto, S.; Valsta, L.M.; Sarlio-Lahteenkorva, S. Nutrition policy in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2010, 13, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberio, A.M.; Sumar, N.; Trieu, K.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Tarasuk, V.; Webster, J.; Campbell, N.; McLaren, L. Population-level interventions in government jurisdictions for dietary sodium reduction: A Cochrane Review. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1405–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Meza, J.; Gonzalez-Rocha, A.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Nilson, E.; Basto-Abreu, A.; Barquera, S.; Denova-Gutiérrez, E. Effective and Scalable Interventions to Reduce Sodium Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2023, 12, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyseni, L.; Elliot-Green, A.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; Kypridemos, C.; O’Flaherty, M.; McGill, R.; Orton, L.; Bromley, H.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Capewell, S. Systematic review of dietary salt reduction policies: Evidence for an effectiveness hierarchy? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e177535. [Google Scholar]

| Number | Food Category | n | Sodium Content (mg/100 g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Range | |||

| 1 | Chocolate, sugar confectionery, and jelly | 154 | 53 | 23–102 | 0–600 |

| 2 | Cake and pastry products | 316 | 179 | 60–280 | 0–851 |

| 2a | Chinese pastries (except for moon cakes) | 135 | 203 | 101–307 | 0–851 |

| 2b | Moon cakes | 97 | 47 | 25–121 | 0–744 |

| 2c | Western-style pastries | 84 | 238 | 187–321 | 53–545 |

| 3 | Biscuits | 359 | 280 | 185–414 | 0–956 |

| 3a | Sandwich biscuits | 71 | 337 | 220–400 | 27–810 |

| 3b | Wafer biscuits | 47 | 155 | 80–240 | 6–492 |

| 3c | Cookies | 39 | 260 | 192–324 | 103–497 |

| 3d | Soda biscuits | 20 | 480 | 417–495 | 278–660 |

| 3e | Egg roll | 16 | 107 | 69–188 | 8–451 |

| 3f | Other biscuits | 166 | 300 | 233–464 | 0–956 |

| 4 | Snack foods | 1191 | 750 | 386–1346 | 0–6120 |

| 4a | Crisps | 99 | 572 | 400–727 | 107–1104 |

| 4b | Extruded snacks (except for crisps) | 283 | 530 | 270–798 | 0–4826 |

| 4c | Nuts and seeds | 256 | 456 | 232–756 | 0–3912 |

| 4d | Extruded flavouring noodles | 223 | 2590 | 2221–2748 | 776–3698 |

| 4e | Preserves | 68 | 345 | 20–1368 | 0–6120 |

| 4f | Dried fruit | 46 | 59 | 16–163 | 0–933 |

| 4g | Soybean curd slab | 216 | 1004 | 827–1325 | 117–2608 |

| 5 | Beverages | 297 | 24 | 13–43 | 0–110 |

| 6 | Edible ices | 41 | 72 | 54–86 | 6–257 |

| 7 | Yogurt, sour milk, and similar foods | 272 | 60 | 50–69 | 32–190 |

| 8 | Cheese | 53 | 363 | 243–515 | 115–1600 |

| 9 | Convenience foods | 608 | 1578 | 798–2073 | 104–6852 |

| 10 | Frozen rice and flour products | 271 | 310 | 54–435 | 0–866 |

| 11 | Cereals | 283 | 67 | 8–150 | 0–800 |

| 12 | Congee | 102 | 50 | 22–512 | 0–2730 |

| 13 | Edible oil | 21 | 0 | 0–0 | 0–0 |

| 14 | Bread and bakery products | 127 | 250 | 205–320 | 95–606 |

| 14a | Sweet breads | 37 | 249 | 186–313 | 95–546 |

| 14b | Leavened breads | 90 | 251 | 212–325 | 101–606 |

| 15 | Fine dried noodles | 322 | 602 | 250–658 | 0–2100 |

| 16 | Processed meat products | 822 | 1323 | 990–1681 | 64–4718 |

| 16a | Cured meat products | 28 | 1987 | 1478–2432 | 700–4718 |

| 16b | Soy sauce and pot-roast meat products | 241 | 1250 | 973–1589 | 89–3160 |

| 16c | Smoked and roasted meat products | 21 | 1022 | 930–1735 | 494–1967 |

| 16d | Sausage meat products | 61 | 1015 | 873–1200 | 484–1967 |

| 16e | Dried meat products | 398 | 1500 | 1238–1792 | 64–3684 |

| 16f | Canned meat | 51 | 800 | 702–858 | 587–1300 |

| 16g | Prepared meat products | 22 | 458 | 306–687 | 269–1170 |

| 17 | Processed poultry products | 732 | 1240 | 980–1573 | 254–3094 |

| 17a | Soy sauce and pot-roast poultry products | 581 | 1296 | 1046–1620 | 254–3094 |

| 17b | Smoked and roasted poultry products | 62 | 1252 | 894–1528 | 301–2898 |

| 17c | Sausage poultry products | 67 | 985 | 857–1100 | 546–1340 |

| 17d | Dried poultry products | 5 | 1536 | 1245–1580 | 1180–1600 |

| 17e | Prepared poultry products | 17 | 693 | 544–940 | 386–1529 |

| 18 | Processed fish products | 611 | 1470 | 994–1800 | 39–6160 |

| 18a | Cooked fish and seafood products | 477 | 1561 | 1160–1860 | 406–6160 |

| 18b | Canned fish | 72 | 1116 | 787–1410 | 168–4000 |

| 18c | Other fish products | 62 | 701 | 238–884 | 39–1948 |

| 19 | Processed egg products | 66 | 741 | 618–907 | 194–2706 |

| 20 | Sauces, dips, and dressings | 1012 | 3896 | 2059–6523 | 0–23,696 |

| 20a | Soy sauces | 231 | 6600 | 5907–7333 | 3140–10,120 |

| 20b | Fermented bean curd | 69 | 3525 | 2975–3932 | 2080–5859 |

| 20c | Pickled vegetables | 255 | 2000 | 1655–2360 | 520–12,646 |

| 20d | Paste and like products | 82 | 6416 | 4045–8007 | 0–12,000 |

| 20e | Compound seasoning | 375 | 3896 | 1690–5447 | 120–23,696 |

| Food Category | Meeting Global Sodium Benchmarks | Not Meeting Global Sodium Benchmarks | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Sodium (mg/100 g) | n | Sodium (mg/100 g) | |||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |||

| Chinese pastries (except for moon cakes) | 39 | 56 | 32–86 | 96 | 280 | 189–464 |

| Moon cakes | 72 | 34 | 19–60 | 25 | 184 | 138–274 |

| Western-style pastries | 29 | 168 | 130–193 | 55 | 300 | 240–354 |

| Sandwich biscuits | 66 | 311 | 218–380 | 5 | 768 | 658–789 |

| Wafer biscuits | 37 | 135 | 66–196 | 10 | 412 | 317–471 |

| Cookies | 22 | 199 | 160–224 | 17 | 325 | 283–373 |

| Soda biscuits | 19 | 480 | 396–480 | 1 | 660 | 660–660 |

| Egg roll | 14 | 102 | 53–168 | 2 | 364 | 320–407 |

| Other biscuits | 141 | 276 | 209–365 | 25 | 699 | 633–747 |

| Crisps | 33 | 360 | 265–408 | 66 | 681 | 572–754 |

| Extruded snacks (except for crisps) | 138 | 267 | 190–409 | 145 | 769 | 645–919 |

| Nuts and seeds | 73 | 138 | 16–197 | 183 | 600 | 433–836 |

| Soybean curd slab | 2 | 174 | 145–202 | 214 | 1005 | 843–1331 |

| Cheese | 46 | 321 | 239–420 | 7 | 972 | 800–1024 |

| Convenience foods | 145 | 530 | 357–733 | 463 | 1849 | 1383–2188 |

| Frozen rice and flour products | 121 | 48 | 14–89 | 150 | 422 | 377–506 |

| Cereals | 259 | 40 | 7–121 | 24 | 321 | 280–413 |

| Congee | 73 | 34 | 11–54 | 29 | 1243 | 684–1909 |

| Edible oil | 21 | 0 | 0–0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Sweet breads | 28 | 224 | 165–256 | 9 | 400 | 326–499 |

| Leavened breads | 70 | 238 | 204–261 | 20 | 383 | 362–411 |

| Cured meat products | 2 | 742 | 721–762 | 26 | 2032 | 1590–2485 |

| Soy sauce and pot-roast meat products | 10 | 396 | 100–422 | 231 | 1266 | 1010–1594 |

| Smoked and roasted meat products | 1 | 752 | 752–752 | 20 | 1237 | 971–1735 |

| Sausage meat products | 1 | 484 | 484–484 | 60 | 1043 | 882–1200 |

| Dried meat products | 2 | 178 | 121–234 | 396 | 1500 | 1239–1792 |

| Canned meat | NA | NA | NA | 51 | 800 | 702–858 |

| Prepared meat products | NA | NA | NA | 22 | 458 | 306–687 |

| Soy sauce and pot-roast poultry products | 13 | 510 | 471–532 | 568 | 1304 | 1062–1645 |

| Smoked and roasted poultry products | 2 | 414 | 357–470 | 60 | 1254 | 900–1549 |

| Sausage poultry products | NA | NA | NA | 67 | 985 | 857–1100 |

| Dried poultry products | NA | NA | NA | 5 | 1536 | 1245–1580 |

| Prepared poultry products | NA | NA | NA | 17 | 693 | 544–940 |

| Canned fish | 4 | 320 | 206–341 | 68 | 1135 | 793–1479 |

| Other fish products | 17 | 124 | 53–194 | 45 | 796 | 619–1016 |

| Soy sauces | 27 | 4520 | 4520–4793 | 204 | 6754 | 6422–7433 |

| Pickled vegetables | 1 | 520 | 520–520 | 254 | 2000 | 1657–2360 |

| Fermented bean curd | NA | NA | NA | 69 | 3525 | 2975–3932 |

| Paste and like products | 8 | 335 | 0–412 | 74 | 6855 | 4479–8517 |

| Compound seasoning | 337 | 3456 | 1460–4720 | 38 | 19,200 | 17,652–20,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ding, X.; Lv, W.; Liu, Y.; Long, J.; Li, H.; Ma, A.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, C. Sodium Content in Pre-Packaged Foods in China: A Food Label Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234862

Ding X, Lv W, Liu Y, Long J, Li H, Ma A, Yang Y, Wang Z, Gao C. Sodium Content in Pre-Packaged Foods in China: A Food Label Analysis. Nutrients. 2023; 15(23):4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234862

Chicago/Turabian StyleDing, Xin, Wanting Lv, Yang Liu, Jiewei Long, Hanning Li, Aiguo Ma, Yuexin Yang, Zhu Wang, and Chao Gao. 2023. "Sodium Content in Pre-Packaged Foods in China: A Food Label Analysis" Nutrients 15, no. 23: 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234862

APA StyleDing, X., Lv, W., Liu, Y., Long, J., Li, H., Ma, A., Yang, Y., Wang, Z., & Gao, C. (2023). Sodium Content in Pre-Packaged Foods in China: A Food Label Analysis. Nutrients, 15(23), 4862. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15234862