National Nutrition Surveys Applying Dietary Records or 24-h Dietary Recalls with Questionnaires: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

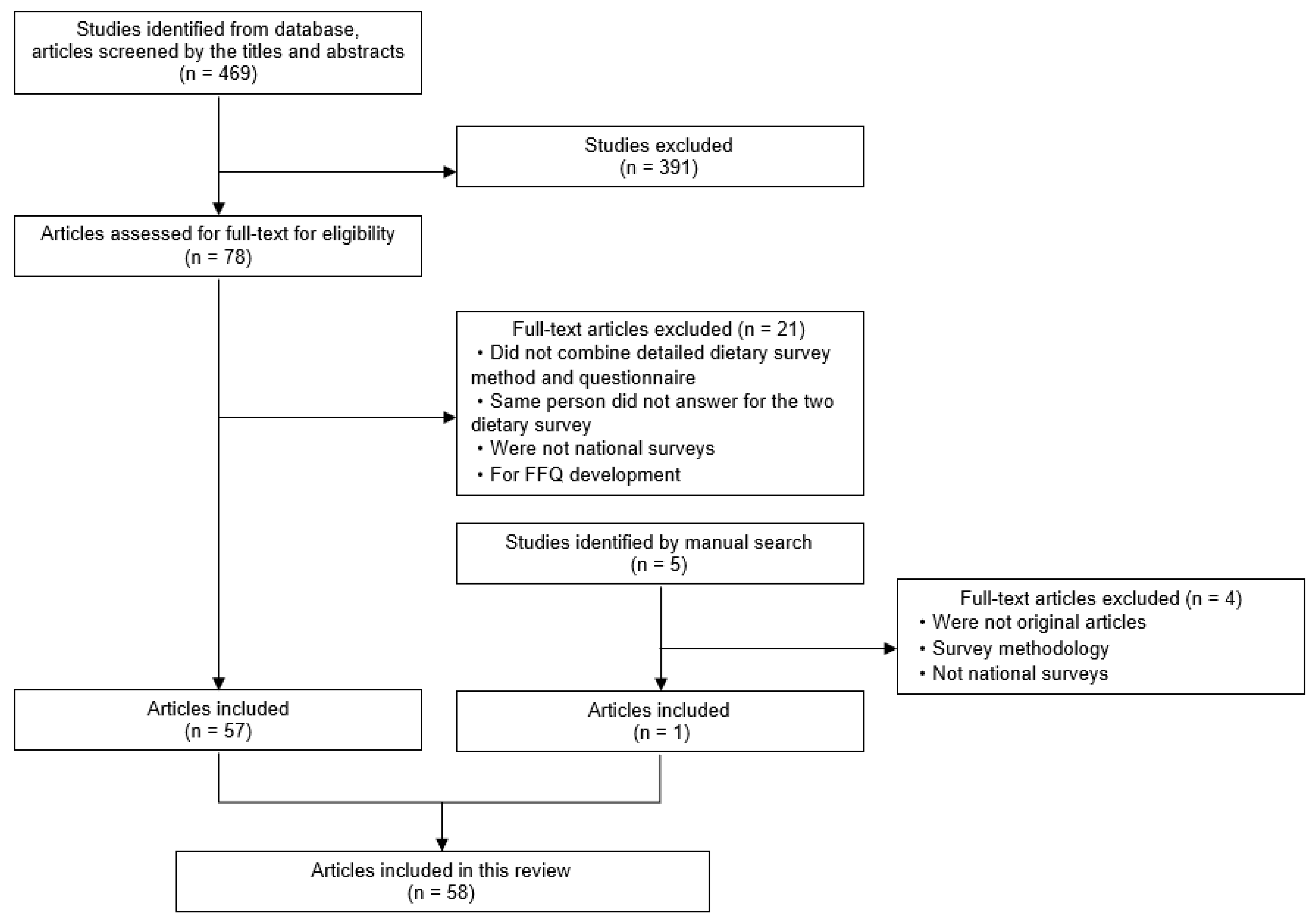

2.3. Selection of Articles

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

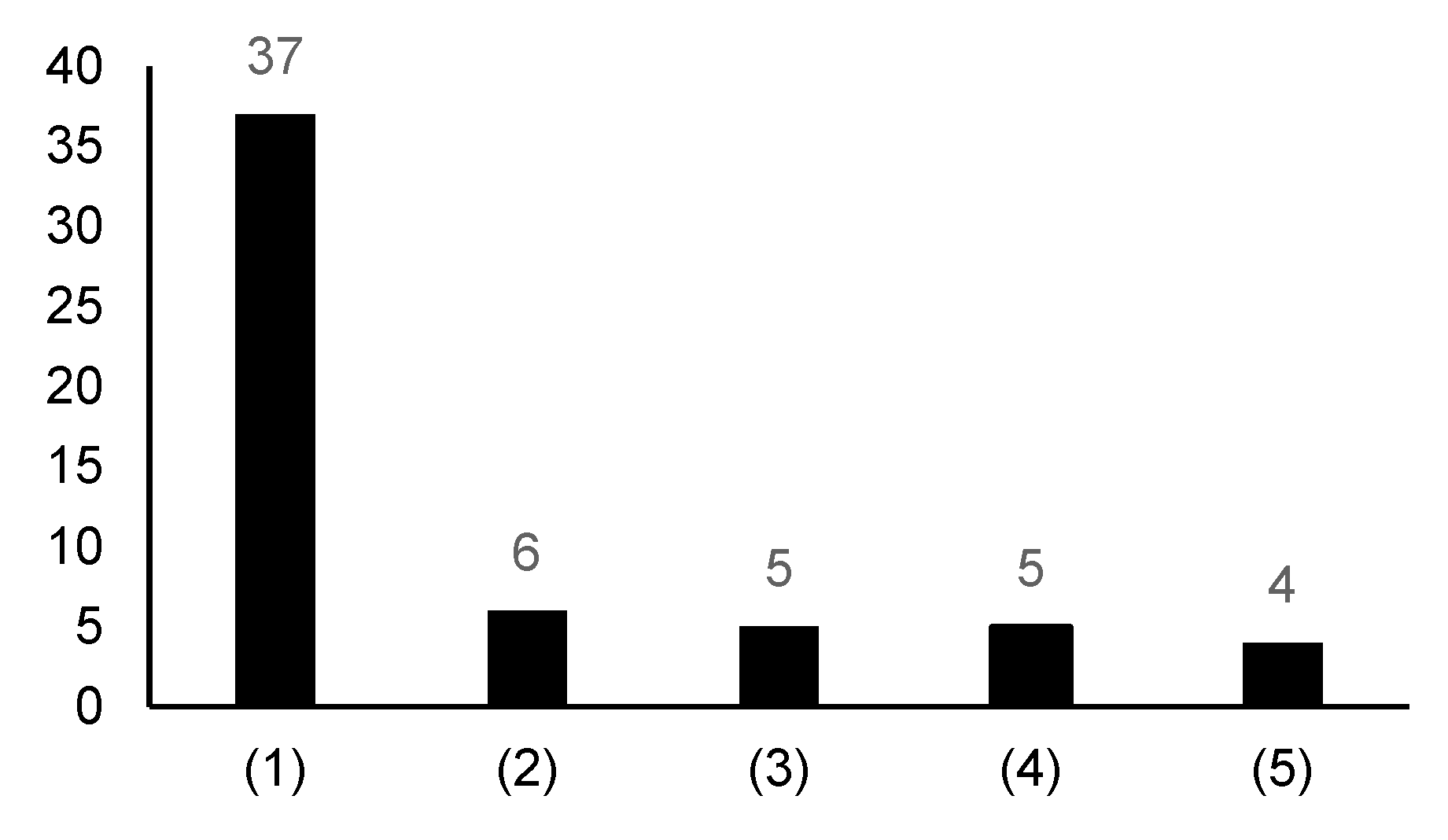

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Limitations of Dietary Survey Methods

3.4. Purpose of Combined Detailed Dietary Survey of Dietary Record or 24-h Dietary Recall and Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rippin, H.L.; Hutchinson, J.; Evans, C.E.L.; Jewell, J.; Breda, J.J.; Cade, J.E. National nutrition surveys in Europe: A review on the current status in the 53 countries of the WHO European region. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 62, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Song, W.O. National nutrition surveys in Asian countries: Surveillance and monitoring efforts to improve global health. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 23, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Health Japan 21 (the Second Term). 2012. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/0000047330.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (2020). 2019. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000862500.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Magriplis, E.; Dimakopoulos, I.; Karageorgou, D.; Mitsopoulou, A.V.; Bakogianni, I.; Micha, R.; Michas, G.; Ntouroupi, T.; Tsaniklidou, S.M.; Argyri, K.; et al. Aims, design and preliminary findings of the Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS). BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. National FinHealth Study. Available online: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-development/research-and-projects/national-finhealth-study (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. Nutrient Recommendations and Databases. Available online: https://ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/nutrientrecommendations.aspx (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Willett, W.C. Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Oxford University: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia, N.; Dwyer, J.; Terry, A.; Moshfegh, A.; Johnson, C. Update on NHANES dietary data: Focus on collection, release, analytical considerations, and uses to inform public policy. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Delfar, N.; Zaletel, M.; Lavtar, D.; Koroušić, S.B.; Golja, P.; Zdešar, K.K.; Pravst, I.; et al. Slovenian national food consumption survey in adolescents, adults and elderly. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. Support. Publ. 2019, 16, EN-172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.Y.; Oh, J.K.; Bae, K.H. Is yogurt intake associated with periodontitis due to calcium? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P.V.; Zhou, Y.; Brooks, B.; McDuffie, C.; Agarwal, K.; Chao, A.M. Relationships among alcohol drinking patterns, macronutrient composition, and caloric intake: National health and nutrition examination survey 2017–2018. Alcohol Alcohol. 2022, 57, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agogo, G.O.; Muoka, A.K. A three-part regression calibration to handle excess zeroes, skewness and heteroscedasticity in adjusting for measurement error in dietary intake data. J. Appl. Stat. 2022, 49, 884–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftfield, E.; Freedman, N.D.; Dodd, K.W.; Vogtmann, E.; Xiao, Q.; Sinha, R.; Graubard, B.I. Coffee drinking is widespread in the United States, but usual intake varies by key demographic and lifestyle factors. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 1762–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Lieberman, H.R. Assessing alcohol intake & its dose-dependent effects on liver enzymes by 24-h recall and questionnaire using NHANES 2001–2010 data. Nutr. J. 2016, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Hollis, J.H.; Jacques, P.F. The associations between yogurt consumption, diet quality, and metabolic profiles in children in the USA. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Thevenet-Morrison, K.; van Wijngaarden, E. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake through fish consumption and prostate specific antigen level: Results from the 2003 to 2010 National Health and Examination Survey. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2014, 91, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappeler, R.; Eichholzer, M.; Rohrmann, S. Meat consumption and diet quality and mortality in NHANES III. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmire, C.A.; Block, R.C.; Thevenet-Morrison, K.; van Wijngaarden, E. Associations between omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids from fish consumption and severity of depressive symptoms: An analysis of the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2012, 86, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, A.R.; Arroyo, C.; Tedders, S.H.; Li, Y.; Dai, Q.; Zhang, J. Dietary protein and protein-rich food in relation to severely depressed mood: A 10 year follow-up of a national cohort. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 35, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, N.L.; Barraj, L.M.; Murphy, M.M.; Bi, X. Dietary acrylamide exposure and hemoglobin adducts—National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2003–04). Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 3098–3108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, R.L.; Dodd, K.W.; Gahche, J.J.; Dwyer, J.T.; McDowell, M.A.; Yetley, E.A.; Sempos, C.A.; Burt, V.L.; Radimer, K.L.; Picciano, M.F. Total folate and folic acid intake from foods and dietary supplements in the United States: 2003–2006. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.J.; Webster, T.F.; McClean, M.D. Diet contributes significantly to the body burden of PBDEs in the general U.S. population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2009, 117, 1520–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, I.H.; Rue, T.C.; Kestenbaum, B. Serum phosphorus concentrations in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laroche, H.H.; Hofer, T.P.; Davis, M.M. Adult fat intake associated with the presence of children in households: Findings from Nhanes III. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2007, 20, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, K.M.; Reiber, G.; Boyko, E.J. Diet and exercise among adults with type 2 diabetes: Findings from the third national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES III). Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1722–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, K.E.; Burt, B.A.; Eklund, S.A. Sugared soda consumption and dental caries in the United States. J. Dent. Res. 2001, 80, 1949–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, E.; Crespo, C.J. Dietary intake and nutritional status of US adult marijuana users: Results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.O.; Kerver, J.M. Nutritional contribution of eggs to American diets. J. Am Coll Nutr. 2000, 19, 556S–562S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doidge, J.C.; Segal, L. Most Australians do not meet recommendations for dairy consumption: Findings of a new technique to analyse nutrition surveys. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2012, 36, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle-Stone, R.; Brown, K.H. Comparison of a Household Consumption and Expenditures Survey with Nationally Representative Food Frequency Questionnaire and 24-hour Dietary Recall Data for Assessing Consumption of Fortifiable Foods by Women and Young Children in Cameroon. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Park, S.; Kim, J.Y. Comparison of dietary share of ultra-processed foods assessed with a FFQ against a 24-h dietary recall in adults: Results from KNHANES 2016. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1166–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.E.; Seo, Y.G. Relationship between egg consumption and body composition as well as serum cholesterol level: Korea national health and nutrition examination survey 2008–2011. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 5918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, E. Association between soft-drink intake and obesity, depression, and subjective health status of male and female adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, A.; Ha, K.; Joung, H.; Song, Y. Frequency of consumption of whole fruit, not fruit juice, is associated with reduced prevalence of obesity in Korean adults. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2019, 119, 1842–1851.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, N.S.; Lee, B.K.; Park, S. Carbohydrate intake exhibited a positive association with the risk of metabolic syndrome in both semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires and 24-hour recall in women. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.K.; Bae, Y.J. Vegetable intake is associated with lower Frammingham risk scores in Korean men: Korea National Health and Nutrition survey 2007–2009. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2016, 10, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, H.J.; Oh, K. Household food insecurity and dietary intake in Korea: Results from the 2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Ha, K.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, C.I.; Joung, H.; Paik, H.Y.; Song, Y. Soft drink consumption is positively associated with metabolic syndrome risk factors only in Korean women: Data from the 2007–2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Metabolism 2015, 64, 1477–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ham, J.O.; Lee, B.K. Effects of total vitamin A, vitamin C, and fruit intake on risk for metabolic syndrome in Korean women and men. Nutrition 2015, 31, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, Y.J. Plain water intake of Korean adults according to life style, anthropometric and dietary characteristic: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 2008–2010. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2014, 8, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Cho, S.; Jacobs, D.R., Jr.; Park, K. Instant coffee consumption may be associated with higher risk of metabolic syndrome in Korean adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 106, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Cho, J.I.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, C.I.; Cho, E. Intakes of dairy products and calcium and obesity in Korean adults: Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES) 2007–2009. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J.; Kim, J. Factors in relation to bone mineral density in Korean middle-aged and older men: 2008–2010 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 64, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.I.; Song, Y.; Kim, W.Y.; Lee, J.E. Association of adherence to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee guidelines with hypertension in Korean men and women. Nutr. Res. 2013, 33, 789–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellou, A.; Papatesta, E.M.; Martimianaki, G.; Peppa, E.; Stratou, M.; Trichopoulou, A. Dietary supplement use in Greece: Methodology and findings from the National Health and Nutrition Survey—HYDRIA (2013–2014). Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 129, 2174–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martimianaki, G.; Peppa, E.; Valanou, E.; Papatesta, E.M.; Klinaki, E.; Trichopoulou, A. Today’s Mediterranean diet in Greece: Findings from the national health and nutrition survey-HYDRIA (2013–2014). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smiliotopoulos, T.; Magriplis, E.; Zampelas, A. Validation of a food propensity questionnaire for the Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS) and results on this population’s adherence to key food-group nutritional guidelines. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjermo, H.; Sand, S.; Nälsén, C.; Lundh, T.; Enghardt Barbieri, H.; Pearson, M.; Lindroos, A.K.; Jönsson, B.A.; Barregård, L.; Darnerud, P.O. Lead, mercury, and cadmium in blood and their relation to diet among Swedish adults. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 57, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjermo, H.; Darnerud, P.O.; Lignell, S.; Pearson, M.; Rantakokko, P.; Nälsén, C.; Enghardt Barbieri, H.; Kiviranta, H.; Lindroos, A.K.; Glynn, A. Fish intake and breastfeeding time are associated with serum concentrations of organochlorines in a Swedish population. Environ. Int. 2013, 51, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorič, M.; Hristov, H.; Blaznik, U.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Delfar, N.; Pravst, I. Dietary intakes of Slovenian adults and elderly: Design and results of the national dietary study SI.Menu 2017/18. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hribar, M.; Hristov, H.; Lavriša, Ž.; Koroušić Seljak, B.; Gregorič, M.; Blaznik, U.; Žmitek, K.; Pravst, I. Vitamin D intake in Slovenian adolescents, adults, and the elderly population. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayasari, N.R.; Bai, C.H.; Hu, T.Y.; Chao, J.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Huang, Y.L.; Wang, F.F.; Tinkov, A.A.; Skalny, A.V.; Chang, J.S. Associations of food and nutrient intake with serum hepcidin and the risk of gestational iron-deficiency anemia among pregnant women: A population-based study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Huang, Y.C.; Su, H.H.; Lee, M.Z.; Wahlqvist, M.L. A simple food quality index predicts mortality in elderly Taiwanese. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2011, 15, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Huang, Y.C.; Wahlqvist, M.L. Chewing ability in conjunction with food intake and energy status in later life affects survival in Taiwanese with the metabolic syndrome. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2010, 58, 1072–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, K.H.; See, L.C.; Huang, Y.C.; Yang, C.H.; Sun, J.H. Dietary factors associated with hyperuricemia in adults. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 37, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, N.; Diouf, F.; Golsong, N.; Höpfner, T.; Lindtner, O. KiESEL—The Children’s Nutrition Survey to Record Food Consumption for the youngest in Germany. BMC Nutr. 2022, 8, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisinger-Watzl, M.; Straßburg, A.; Ramünke, J.; Krems, C.; Heuer, T.; Hoffmann, I. Comparison of two dietary assessment methods by food consumption: Results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haftenberger, M.; Heuer, T.; Heidemann, C.; Kube, F.; Krems, C.; Mensink, G.B. Relative validation of a food frequency questionnaire for national health and nutrition monitoring. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parackal, S.M.; Smith, C.; Parnell, W.R. A profile of New Zealand “Asian” participants of the 2008/9 Adult National Nutrition Survey: Focus on dietary habits, nutrient intakes and health outcomes. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, L.F.; Lande, B.; Arsky, G.H.; Trygg, K. Validation of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire used among 12-month-old Norwegian infants. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, C.; Castetbon, K.; Desbouys, L.; Rouche, M.; Vandevijvere, S. The cost of diets according to nutritional quality and sociodemographic characteristics: A population-based assessment in Belgium. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2021, 121, 2187–2200.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bel, S.; De Ridder, K.A.A.; Lebacq, T.; Ost, C.; Teppers, E.; Cuypers, K.; Tafforeau, J. Habitual food consumption of the Belgian population in 2014–2015 and adherence to food-based dietary guidelines. Arch Public Health 2019, 77, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temme, E.; Huybrechts, I.; Vandevijvere, S.; De Henauw, S.; Leveque, A.; Kornitzer, M.; De Backer, G.; Van Oyen, H. Energy and macronutrient intakes in Belgium: Results from the first National Food Consumption Survey. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1823–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vandevijvere, S.; De Vriese, S.; Huybrechts, I.; Moreau, M.; Temme, E.; De Henauw, S.; De Backer, G.; Kornitzer, M.; Leveque, A.; Van Oyen, H. The Gap between food-based dietary guidelines and usual food consumption in Belgium, 2004. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labadarios, D.; Steyn, N.P.; Maunder, E.; MacIntryre, U.; Gericke, G.; Swart, R.; Huskisson, J.; Dannhauser, A.; Vorster, H.H.; Nesmvuni, A.E.; et al. The National Food Consumption Survey (NFCS): South Africa, 1999. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo-Solís, C.I.; Monterrubio-Flores, E.A.; Cediel, G.; Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Barquera, S. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire to estimate dietary intake according to the NOVA classification in Mexican children and adolescents. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E.; Ramírez-Silva, I.; Rodríguez-Ramírez, S.; Jiménez-Aguilar, A.; Shamah-Levy, T.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Validity of a food frequency questionnaire to assess food intake in Mexican adolescent and adult population. Salud Publica Mex. 2016, 58, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, M.K.; Adamson, A.J.; Poliakov, I.; Bradley, J.; Simpson, E.; Olivier, P.; Foster, E. Field testing of the use of Intake24—An online 24-hour dietary recall system. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.K.; Park, J.Y.; Nicolas, G.; Paik, H.Y.; Kim, J.; Slimani, N. Adapting a standardised international 24 h dietary recall methodology (GloboDiet software) for research and dietary surveillance in Korea. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1810–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J.K.; English, D.R.; Fahey, M.T.; Forbes, A.B.; Gurrin, L.C.; Simpson, J.A.; Brinkman, M.T.; Giles, G.G.; Hodge, A.M. Validity and calibration of the FFQ used in the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2357–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and Operations, 1999–2010. 2013. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_01/sr01_056.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Kweon, S.; Kim, Y.; Jang, M.J.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Khang, Y.H.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. FinHealth 2017 Study—Methods. 2019. Available online: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/139084/URN_ISBN_978-952-343-449-3.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 9 October 2023).

- Koshida, E.; Tajima, R.; Matsumoto, M.; Takimoto, H. Global Comparison of Nutrient Reference Values, Current Intakes, and Intake Assessment Methods for Sodium among the Adult Population. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2023, 69, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Z.; Huo, J.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; He, L.; Sun, J.; et al. Data resource profile: China national nutrition surveys. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 368–368f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- French Agency on Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (ANSES); Dubuisson, C.; Carrillo, S.; Dufour, A.; Havard, S.; Pinard, P.; Volatier, J.L. The French dietary survey on the general population (INCA3). Eur. Food Saf. Auth. Support. Publ. 2017, 14, EN-1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Publication Year | Country | Survey Name | Study Year | Study Population and Sample Sizes | Study Aims | Detailed Dietary Survey Method of Dietary Record or 24-h Dietary Recall | Dietary Survey Method Using Questionnaire | How to Use the Dietary Survey Results from Dietary Record or 24-h Dietary Recall and Questionnaire | Limitations of the Dietary Survey Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kanellou et al., 2022 [49] | Greece | National Health and Nutrition Survey (HYDRIA) | 2013–2014 | 4011 adults aged ≥18 years (1873 males and 2138 females) | To examine the relationship between dietary supplement intake and lifestyle, health status, and eating habits | Two 24-h dietary recalls | The FPQ and supplement use questionnaire | 24-h dietary recall: estimate dietary supplement use (frequency and quantity) FPQ: evaluate dietary supplement use (frequency and quantity) Questionnaire: evaluate dietary supplement use (frequency and quantity) | NA |

| Joseph et al., 2022 [15] | US | NHANES | 2017–2018 | 2320 adults aged ≥18 years | To examine the association between alcohol consumption thresholds and macronutrient composition, energy intake, and anthropometric measures | Two 24-h dietary recalls | Alcohol use questionnaire | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake Questionnaire: evaluate frequency and amount of alcohol consumption | There is a lack of specific data on macronutrient composition in alcoholic and non-alcoholic diets and the exact energy intake from different types of alcohol. |

| Gregorič et al., 2022 [54] | Slovenia | SI.Menu 2017/18 | 2017–2018 | 364 adults aged 18–64 years (173 males and 191 females) and 416 older adults aged 65–74 years (213 males and 203 females) | To assess Slovenian adults and older adults’ dietary habits regarding food consumption and energy and macronutrient intakes | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FPQ | Both 24-h recalls and FPQs were used to estimate usual food and nutrient intakes. 24-h dietary recall: estimate usual daily dietary intake of foods and nutrients FPQ: evaluate usual daily dietary intake of foods and nutrients | The 24-h recall method is susceptible to reporting bias. Slow processing speed of upgraded OPEN software for SI.Menu projects may affect food matching and accuracy. Open-ended food selection and web-based recalls may lead to variations of the results. Recipes from the same country may differ due to diverse methods and ingredients. |

| Nowak et al., 2022 [60] | Germany | The Children’s Nutrition Survey to Record Food Consumption (KiESEL) | 2014–2017 | 1104 children aged 6 months to 5 years (560 boys and 544 girls) | To update German children’s consumption data for use in exposure (e.g., contaminants, pesticides or microbial risks) assessment | Three consecutive days and an unrelated fourth day of dietary records | FPQ | FPQ: evaluate frequency of consumption of foods that were rarely eaten, including offal of various animals or foods, and various teas and herbal infusions | NA |

| Oviedo-Solís et al., 2022 [70] | Mexico | Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey (Ensanut 2012) | 2011–2012 | 217 children aged 5–11 years and 165 adolescents aged 12–19 years | To evaluate the relative validity of a semi-quantitative FFQ compared with two 24-h dietary recalls for estimating dietary intake in each NOVA food group in Mexican children and adolescents | Two 24-h dietary recalls | Semi-quantitative FFQ | Evaluation of agreement of energy and nutrient intakes estimated by the FFQ and the 24-h recall method 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy and nutrient intakes FFQ: estimate energy and nutrient intakes | Since not all cooking methods were covered, it is likely that some foods were misclassified among the NOVA groups. In some cases, it was unclear whether the food was prepared at home or commercially available. |

| Martimianaki et al., 2022 [50] | Greece | National Health and Nutrition Survey (HYDRIA) | 2013–2014 | 4011 adults aged 18–94 years (1873 males and 2138 females) | To assess the level of adherence to the traditional Greek Mediterranean diet by examining the food and macronutrient intake of the Greek population | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Non-quantitative FFQ | The frequency of foods from the FFQ was incorporated into the model to supplement the food intakes from the 24-h dietary recalls. 24-h dietary recall: estimate food intakes and the usual distribution intake of food groups and subgroups FFQ: evaluate frequency of foods | It was not possible to differentiate between refined grains and whole grains in the cereal and products food groups. |

| Jung et al., 2022 [35] | Korea | KNHANES | 2016 | 3189 adults aged 19–64 years (1215 males and 1974 females) | To evaluate the performance of the FFQ to estimate the contribution of NOVA groups in an individual’s diet compared to a single 24-h dietary recall, with a particular focus on ultra-processed foods | One 24-h dietary recall | Dish-based semiquantitative FFQ | Four NOVA groups were categorized and mean differences, correlation coefficients, and co-classifications between FFQ and 24-h recall for energy and nutrient intakes in each group were calculated. 24-h dietary recall: estimate all food and beverage intakes FFQ: evaluate all food and beverage intakes | Misclassification of NOVA groups, including UPF, was possible because the FFQ was not designed for the NOVA system. Findings may not apply to the food-based FFQ, and neither the single 24-h recall nor the FFQ was the gold standard for dietary intake. |

| Shim et al., 2021 [36] | Korea | KNHANES | 2008–2011 | FFQ: 13,132 adults (5407 males and 7725 females), 24-h dietary recall: 13,366 adults (5522 males and 7844 females) aged ≥19 years | To analyze the relationship between egg consumption, body composition, and serum cholesterol levels | One 24-h dietary recall | Non-quantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: assess egg intake (not consumed or consumed) FFQ: evaluate frequency of egg consumption | Questionnaire-based data may have recall bias. |

| Pedroni et al., 2021 [65] | Belgium | Belgian National Food Consumption Survey (BNFCS—2014) | 2014–2015 | 1158 adults aged 18–64 years | To estimate differences in costs per diet quality and identify sociodemographic characteristics associated with cost differences in adult diets | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: calculate the traditional Mediterranean Diet Score, Healthy Diet Indicator, and average daily dietary costs FFQ: calculate the traditional Mediterranean Diet Score | The food group definitions may be outdated, lacking differentiation between whole and refined grains and not accounting for ultra-processed foods. |

| Hribar et al., 2021 [55] | Slovenia | SI.Menu 2017/18 | 2017–2018 | 1248 participants (468 adolescents (238 males and 230 females) aged 10–17 years, 364 adults (173 males and 191 females) aged 18–64 years, 416 older adults (213 males and 203 females) aged 65–74 years) | To estimate vitamin D intake, identify food groups that contribute significantly to vitamin D intake, and predict the impact of a hypothetical milk fortification mandate | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FPQ | Vitamin D intake was estimated using data from the 24-h recalls and FPQ. 24-h dietary recall: estimate vitamin D intake and vitamin D food intakes of usual diet using the Multiple Source Method FPQ: evaluate vitamin D intake and vitamin D food intakes of usual diet using the Multiple Source Method | The FPQ data did not include eating frequency for some important vitamin D sources, like eggs. Vitamin D content was estimated from a food composition database, not laboratory analysis. Only dietary vitamin D intake was considered, excluding pharmaceuticals and dietary supplements. |

| Mayasari et al., 2021 [56] | Taiwan | Pregnant NAHSIT | 2017–2019 | 1430 pregnant women aged ≥15 years | To investigate the relationship between food and nutrient intake and serum hepcidin levels for iron status on a population scale | One 24-h dietary recall | Interviewer-administrated nonquantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake FFQ: evaluate food intake frequency | A single 24-h recall dataset was utilized. Self-reported dietary data may lead to recall bias and underreporting of energy intake, particularly among overweight or obese individuals in late pregnancy. Pregnant women might overreport dietary intake in the FFQ. |

| Kim et al., 2021 [37] | Korea | KNHANES | 2016 | 3086 adults aged 18–64 years (1186 males and 1900 females) | To explore the association between soft-drink consumption and obesity, depression, and subjective health status | One 24-h dietary recall | Quantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate total energy and nutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate soft drink intake frequency, serving size, and daily intake | Although various sweetened beverages were provided for sugar intake, the relevance of sugar intake was limited to soft-drink intake alone. |

| Agogo et al., 2020 [16] | US | NHANES | 2003–2004 | 1605 women aged 12–49 years | To propose three-part regression calibration models to handle excess zeroes, skewness, and heteroscedasticity in adjusting for measurement error in dietary intake data | 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | To account for exposure measurement error, several methods were compared: the FFQ method, 24-h recall method, 2-part RC method, and 3-part RC-het-prob method. | NA |

| Smiliotopoulos et al., 2020 [51] | Greece | Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey (HNNHS) | 2013–2015 | 3796 participants aged ≥6 months (1543 males and 2253 females) | To examine the validity of the qualitative FPQ developed to assess the dietary habits of the general population and assess the intake of specific food groups regarding guidelines | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FPQ | Comparison of dietary intake from FPQ with 24-h dietary recall and evaluation of agreement of two methods | This FPQ is a qualitative assessment tool and cannot be used alone for quantitative measurements of energy and macronutrient intakes. |

| Choi et al., 2019 [38] | Korea | KNHANES | 2012–2015 | 10,460 adults aged 19–64 years (4082 males and 6378 females) | To examine the associations of frequency of consumption of whole fruit and fruit juice with obesity and metabolic syndrome | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy and macronutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate frequency of whole fruit and fruit juice consumption | The study could not assess whether fruit juices were 100% pure. The frequency of whole fruit and juice consumption relied on a single question, potentially leading to misclassification. Misreporting in dietary intake and energy and macronutrient intakes was possible due to the use of a single 24-h recall that may not represent usual intake. |

| Bel et al., 2019 [66] | Belgium | Second National Food Consumption Survey | 2014–2015 | 2154 adolescents and adults aged 10–64 years and 992 children aged 3–9 years | To evaluate the habitual food consumption in the general population and to compare it with food-based dietary guidelines and results of the 2004 Food Consumption Survey | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls (10 to 64 years) and two self-administered non-consecutive one-day food diaries (3 to 9 years) | FFQ | The distribution of habitual food consumption was estimated to combine 24-h recall and FFQ data based on statistical models accounting for within-subject variation. | The difference between habitual consumption and recommendations may be due to under-reporting of food intake. |

| Ahn et al., 2017 [39] | Korea | KNHANES | 2012–2014 | 10,286 adults aged 19–64 years (3996 males and 6290 females) | To compare the usual nutrient intake in both the semi-quantitative FFQ and 24-h recall methods and determine the association between metabolic syndrome risk and nutrient intake calculated by both methods | 24-h dietary recall | Semi-quantitative FFQ | Evaluate the correlation of nutrient intake between 24-h recall and the FFQ and examine the association of metabolic syndrome with nutrient intake from the two methods | The FFQ included meals prepared using different recipes in the same food group; nutrient intakes could be underestimated or overestimated due to variations in seasonings among recipes. |

| Kim et al., 2017 [14] | Korea | KNHANES | 2009 | 6150 adults aged ≥19 years | To determine whether the lower intakes of yogurt, milk, and calcium were associated with periodontitis | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate calcium intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of yogurt and milk intake | Calcium intake in the KNHANES data could only be estimated based on the Korean dietary reference intakes. A single 24-h recall may not accurately reflect habitual calcium intake due to the short survey duration and reliance on individual memory. |

| Denova-Gutiérre et al., 2016 [71] | Mexico | Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey (Ensanut 2012) | 2012 | 178 adolescents and 230 adults aged ≥20 years | To assess the validity of a 140-item semiquantitative FFQ | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Semi-quantitative FFQ | Evaluation of agreement of intakes of energy, macro-, and micronutrients from two methods 24-h dietary recall: used as a standard to measure the relative validity of the FFQ | The 24-h dietary recall and FFQ had several sources of error, including reliance on memory and perception of portion size. Reproducibility could not be assessed because the FFQ was not conducted twice. |

| Loftfield et al., 2016 [17] | US | NHANES | 2002–2003, 2005–2006, 2011–2012 | 6219 adults aged ≥20 years | To estimate usual daily coffee intakes from all coffee-containing beverages, including decaffeinated and regular coffee, based on demographic, socioeconomic, and health-related factors | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate coffee intake FFQ: evaluate coffee drinking/not drinking | Self-reported dietary assessment methods tended to introduce measurement error. A single 24-h dietary recalls overestimated the proportion of nondrinkers. Caffeine in coffee was not assessed. |

| Agarwal et al., 2016 [18] | US | NHANES | 2001–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010 | 24,807 adults aged ≥19 years (12,561 males and 12,246 females) | To examine alcohol’s dose-dependent effects on markers of liver function, as well as to compare the different methods of assessing alcohol intake | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Alcohol consumption questionnaire | Alcohol intake was assessed in three ways: (1) using a single 24-h recall, estimating self-reported alcohol consumption on the day of the recall; (2) using two days of 24-h recalls, estimating long-term intake through the NCI method; and (3) using an alcohol intake questionnaire to quantify annual consumption. | Alcohol intake was often underestimated, which can lead to bias in self-reported intakes. |

| Choi et al., 2016 [40] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2009 | 2510 male adults aged 40–64 years | To investigate the daily intake of vegetables on a national level and its effect on the risk of CHD, as determined by the Framingham Risk Score | 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate intakes of carbohydrate, protein, fat, and dietary fiber and dividing into salted and non-salted vegetables FFQ: divide into green and white vegetables | Vegetable intake was only quantitatively evaluated. The 24-h recall method is based on a retrospective method; thus, participant intake may have been difficult to accurately reflect. |

| Kim et al., 2015 [41] | Korea | KNHANES | 2012 | 7118 participants aged ≥1 year | To examine the prevalence of household food insecurity and compare dietary intake by food security status | One 24-h dietary recall | Semi-quantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate intakes of energy and nutrients FFQ: evaluate food and nutrient intakes | The FFQ did not include data on children and older adults. |

| Chung et al., 2015 [42] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2011 | 13,972 adults aged ≥30 years (5432 males and 8540 females) | To examine the association between sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and metabolic syndrome risk factors | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of soft drink intake | Soft drink consumption was defined based on a single question, as the FFQ did not include information on other types of sugar-sweetened beverages. Fruit juices were not included as soft drink consumption. |

| Engle-Stone et al., 2015 [34] | Cameroon | National dietary survey | 2009 | 24-h dietary recall: 912 females aged 15–49 years and 882 children aged 12–59 months FFQ: 901 females aged 15–49 years and 901 children aged 12–59 months | To compare apparent consumption of fortifiable foods estimated from the Third Cameroon Household Survey (ECAM3) conducted in 2007 with the results of a national dietary survey using the food frequency questionnaire and 24-h recall methods | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | Comparison FFQ and 24-h recall data with ECAM3 data24-h dietary recall: estimate amount of four fortifiable foods consumed (refined vegetable oil, wheat flour, sugar, and bouillon cube) FFQ: evaluate frequency of consumption of four fortifiable foods | Total nutrient intakes were not compared. |

| Zhu et al., 2015 [19] | US | NHANES | 2003–2004, 2005–2006 | 5124 children aged 2–18 years | To examine the associations between yogurt consumption, diet quality, and metabolic profiles in children | At least one 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy intake and assessment of diet quality FFQ: evaluate frequency of yogurt consumption | The FFQ was not quantitative and did not differentiate between type of yogurt (plain yogurt, probiotic yogurt, etc.). |

| Parackal et al., 2015 [63] | New Zealand | National Nutrition Survey (NZANS) | 2008–2009 | 2995 adolescent and adults aged ≥15 years (1308 males and 1687 females) | To investigate similarities and differences in dietary habits, nutrient intakes, and health outcomes by ethnic group and examine differences within the Asian subgroups based on duration of residence | At least one 24-h dietary recall | Dietary habits questionnaire | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intakes Dietary habits questionnaire: evaluate frequency of food intake | A single 24-h recall did not capture usual intake and could underreport. |

| Eisinger-Watzl et al., 2015 [61] | Germany | German National Nutrition Survey II | 2005–2007 | 9968 participants aged 14–80 years | To compare the updated version of the diet history method and the 24-h recall method | Two 24-h dietary recalls | Semi-quantitative diet history | Evaluate the agreement of dietary intake of the two methods (24-h recalls and diet history) | NA |

| Park et al., 2015 [43] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2009, 2010–2012 | 27,656 adults aged ≥20 years (1308 males and 1687 females) | To assess whether the intake of vitamin A (including β-carotene), vitamin C, fruits, or vegetables was negatively associated with metabolic syndrome | 24-h dietary recall | Semi-quantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy and nutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate frequency of intake of green vegetables, white vegetables, and fruits | The 24-h recall method is based on memory and may lead to underestimation or overestimation; thus, bias may have occurred in the determination of typical nutrient intakes. The FFQ could have caused misclassification, potentially overestimating fruit and vegetable intake. |

| Kim et al., 2014 [44] | Korea | KNHANES | 2008–2010 | 14,428 adults aged 20–64 years (5917 males and 8511 females) | To provide useful insights into plain water intake based on lifestyle, anthropometric, and dietary characteristics | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate food and nutrient intakes and diet quality FFQ: evaluate frequency of beverage intake, such as coffee and tea | The periods for which the plain water intake and 24-h recall methods were evaluated differed. A single 24-h recall did not provide an accurate estimate of usual intake. |

| Kim et al., 2014 [45] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2011 | 17,953 adults aged 19–65 years | To investigate the relationship between coffee consumption and metabolic syndrome and its components | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate intakes of sugar/syrup, coffee creamer, and milk and classification of coffee drinkers FFQ: classification of coffee drinkers | Using only one 24-h recall may have led to an underestimate of consumption. |

| Patel et al., 2014 [20] | US | NHANES | 2003–2010 | 4525 males ≥40 years | To evaluate prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels with fish consumption (the primary source of n-3 PUFAs) and calculated PUFA intake | Two 24-h dietary recalls | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate EPA and DHA FFQ: evaluate specific types of fish consumed | Both the FFQ and 24-h dietary recall may have limitations because they capture relatively short-term exposure. |

| Lee et al., 2014 [46] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2009 | 7173 adults aged 19–64 years (3400 males and 3773 females) | To investigate the association between dairy products and calcium intake and obesity | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate dairy product intake and intakes of total calcium, non-dairy calcium, and dairy calcium FFQ: evaluate frequency of milk and yogurt intake | NA |

| Yang et al., 2014 [47] | Korea | KNHANES | 2008–2010 | 2305 males aged 50–79 years | To investigate general determinants and dietary factors that influenced bone mineral density | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate frequency of food intakes | Nutrient intake was estimated using a single-day 24-h recall. Because KNHANES does not ask about dietary supplement intake, calcium and vitamin D dietary supplement intake was not considered in the overall intake. |

| Kim et al., 2013 [48] | Korea | KNHANES | 2007–2008 | 500 hypertensive (269 males and 231 females) and 4567 normotensive (1749 males and 2818 females) participants aged ≥20 years | To examine the hypothesis that adherence to the JNC-7 guidelines is associated with hypertension | One 24-h dietary recall | Non-quantitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy and nutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate frequency of intake by food (group) | There could have been measurement errors in the 24-h dietary recalls or FFQs. |

| Bjermo et al., 2013 [52] | Sweden | Riksmaten 2010–2011 | 2010–2011 | 273 participants aged 18–80 years (128 males and 145 females) | To examine the bodily burden of lead, mercury, and cadmium in blood and the association between blood levels, diet, and other lifestyle factors | Four-day food records | FFQ; questions regarding less frequency consumed items (e.g., consumption frequency of different classes of fish and meat) | Food records: estimate alcohol, vegetable, and meat intakes FFQ: evaluate less frequently consumed foods (game and fish) | NA |

| Kappeler et al., 2013 [21] | US | NHANES | 1986–2010 | 17,611 participants ≥18 years (8239 males and 9372 females) | To evaluate the association of meat intake and healthy eating index with total mortality, cancer, and cardiovascular disease | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: calculate the healthy eating index score FFQ: evaluate frequency of food intake | NHANES III used an FFQ to assess food consumption, but it could not determine portion sizes. The healthy eating index scores relied on a single 24-h dietary recall. |

| Bjermo et al., 2013 [53] | Sweden | Riksmaten 2010-2011 | 2010–2011 | 246 adults with an average age of 50 (113 males and 133 females) | To investigate the bodily burden of several POPs and their association with diet and other lifestyle factors | Four consecutive days food records | FFQ | Food records: estimate intakes of fat from various animal food groups (i.e., fish, meat, egg, sausage, offal, and poultry) and pollutant concentrations FFQ: evaluate less frequently consumed food items (e.g., fish, meat) | Although the POPs serum concentrations represent long-term exposure prior to blood sampling, dietary patterns were recorded for only four days on one occasion. Intake of less commonly eaten fish may have been underestimated in the food records. |

| Doidge et al., 2012 [33] | Australia | National Nutrition Survey (NNS) | 1995 | 9096 participants aged ≥12 years | To describe the pattern of dietary consumption in Australians and assess the extent to which the population met the national recommendations | At least one 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | Estimate distribution of dairy consumption by age and gender using FFQ and 24-h recall data 24-h dietary recall: estimation of food and nutrient intakes FFQ: evaluate frequency of consumption of foods and supplements | Grouping all dairy foods together assumed that participants consumed milk-, cheese-, and yogurt-based products in the same relative proportions. |

| Hoffmire et al., 2012 [22] | US | NHANES | 2005–2008 | 9276 adults aged ≥20 years | To assess the association between fish consumption and depressive symptoms | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy and nutrient intakes, including EPA + DHA FFQ: determining the intake of different types of fish | Both FFQ and dietary recall captured short-term fish intake and were not suitable for quantifying more chronic (over years) intake. |

| Lee et al., 2011 [57] | Taiwan | Elderly Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT 1999/2000) | 1999–2000 | 1743 older adults aged ≥ 65 years (860 males and 883 females) | To assess the relative predictive ability for mortality of the Overall Dietary Index—Revised (ODI-R) and the Dietary Diversity Score (DDS). | At least one 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | Age- and gender-specific serving sizes for each food group obtained from the 24-h recall were applied to the FFQ. 24-h dietary recall: derive a DDS FFQ: calculate the number of food group servings and nutrient intakes required for the ODI-R score | The dietary information was collected based on food-nutrient categories rather than specific individual foods, and the DDS did not distinguish between soy and animal-derived foods. |

| Wolfe et al., 2011 [23] | US | National Health and Nutrition Evaluation Survey Epidemiologic Follow-up Study (NHEFS) | 1971–1984 (follow-up period: 1982–1984) | 4856 adults aged 25–74 years (1947 males and 2909 females) | To examine the effect of dietary protein and protein-rich food on severely depressed mood | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of consuming high-protein food | Food intake was assessed only once at baseline, potentially introducing measurement error due to self-reporting. Protein sources (animal and vegetable proteins) were not differentiated. |

| Tran et al., 2010 [24] | US | NHANES | 2003–2004 | 5306 participants (1019 children aged 3–12 years, 1201 adolescents aged 13–19 years (561 males and 640 females), 3086 adults aged ≥20 years (1408 males and 1678 females)) | To evaluate the relationship between dietary acrylamide (AA) and hemoglobin adducts | At least one 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | The FFQ data and the quantities of food consumed per eating occasion or day, assessed from the 24-h dietary recall, were combined with AA concentration data to estimate long-term (usual) AA dietary exposure. | A potential limitation of using a self-reporting tool like the FFQ is the possibility of reporting bias, which can affect the accuracy of intake measurements. |

| Haftenberger et al., 2010 [62] | Germany | German National Nutrition Monitoring (NEMONIT) | 2008–2011 | 161 adults aged 18–79 years (82 males and 79 females) | To examine the relative validity of an FFQ developed for use in the German Health Examination Survey for Adults 2008-2011 | Two 24-h dietary recalls (in four consecutive waves) | Semi-quantitative FFQ | Comparison of food intake from FFQ with 24-h dietary recall and ranking evaluation of agreement of food groups from two methods | Both the FFQ and the 24-h dietary recall shared similar error sources, including the reliance on memory and the perception of portion sizes. The FFQ depended on participants’ capability to quantify how much they ate of individual foods and mixed dishes. |

| Lee et al., 2010 [58] | Taiwan | Elderly Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT 1999/2000) | 1999–2000 | 1410 older adults aged ≥65 years (729 males and 681 females) | To examine chewing ability and survival in older adults and consider any interaction with the metabolic syndrome | 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: derive the Dietary Diversity Score FFQ: evaluate frequency of food intake | NA |

| Temme et al., 2010 [67] | Belgium | Belgian National Food Consumption Survey (BNFCS) | 2004 | 3245 participants aged ≥15 years (1623 males and 1622 females) | To evaluate current dietary energy and macronutrient intakes and compare them with the national dietary guidelines and to describe the main food sources of the macronutrients | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FFQ | NA | NA |

| Bailey et al., 2010 [25] | US | NHANES | 2003–2004, 2005–2006 | 11,462 participants aged ≥ 14 years (5910 males and 5552 females) | To combine data on dietary folate and folic acid from dietary supplements with the use of the bias-corrected best power method to adjust for within-person variability | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Dietary supplement questionnaire | 24-h dietary recall: estimate dietary folate intake FFQ: evaluate average daily intake of folic acid derived from supplements | Dietary intake estimates were adjusted for within-individual variation to reflect usual intake. Folate in food estimates and folic acid content in dietary supplements were primarily based on label values. |

| Fraser et al., 2009 [26] | US | NHANES | 2003–2004 | PBDE data: 2040 (994 males and 1046 females), 24-h recall data: 1971 (964 males and 1007 females), FFQ data 1536 (707 males and 829 females) | To evaluate the dietary contribution to PBDE bodily burdens in the United States by linking serum levels to food intake. | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate absolute food and nutrient intakesFFQ: evaluate average intakes of food over a longer period of time | Although 24-h food records aimed for accuracy over a short period, they did not fully represent usual diets and could lead to exposure misclassification when long-term diet was more appropriate. However, the FFQ estimated food consumption over the previous year. |

| de Boer et al., 2009 [27] | US | NHANES | 1988–1994 | 15,513 adults aged ≥20 years | To examine nutritional variables and cardiovascular risk factors regarding circulating serum phosphorus concentrations | 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate intakes of total energy, macronutrients, phosphorus, and alcohol FFQ: evaluate food intakes | Dietary surveys were imprecise. |

| Vandevijvere et al., 2009 [68] | Belgium | Belgian National Food Consumption Survey (BNFCS) | 2004 | 3245 adolescents and adults aged ≥15 years | To evaluate the gap between food-based dietary guidelines and usual food consumption | Two non-consecutive 24-h dietary recalls | FFQ | FFQ data were used to determine the percentage of individuals consuming specific foods daily. 24-h dietary recall: estimate food groups intake FFQ: assess the percentage of persons who consume certain foods on a daily basis | NA |

| Yu et al., 2008 [59] | Taiwan | Nutrition and Health Survey in Taiwan (NAHSIT) | 1993–1996 | 2176 adults aged 19–64 years (987 males and 1189 females) | To clarify the dietary factors associated with hyperuricemia | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ for food groups and FFQ for alcohol consumption | The associations between food intakes derived from each dietary survey and hyperuricemia were examined. 24-h dietary recall: estimate energy, nutrient, and food group intakeFFQ: evaluate food group | The purine content of food was not included in the Nutrient Composition Data Bank for Foods of the Taiwan Area database. |

| Laroche et al., 2007 [28] | US | NHANES | 1988–1994 | 6660 adults aged 17–65 years (52% females) | To compare dietary fat intake between adults with and without minor children in the home | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate intake of total fat, saturated fat, and kilocalories FFQ: evaluate frequency of high-fat foods | Only one 24-h dietary recall was available per individual. Food frequency analysis was restricted to NHANES dataset questions, and some food groups had options with variable fat content. |

| Labadarios et al., 2005 [69] | Republic of South Africa | National Food Consumption Survey (NFCS) | 1999 | 2894 children aged 1–9 years | To determine the nutrient intake and anthropometric status of children and factors that influence their dietary intake | Three separate 24-h dietary recalls | Qualitative FFQ | Comparison of FFQ data with 24-h dietary recall data 24-h dietary recall: evaluate food intake FFQ: estimation of energy, nutrient, and food intakes | NA |

| Andersen et al., 2003 [64] | Norway | NA | 1999 | 64 infants aged 12 months (26 boys and 37 girls) | To assess the validity of a semi-quantitative FFQ used in a large nation-wide dietary survey among 12-month-old Norwegian infants | Seven-day weighed food records | Semi-quantitative FFQ | Evaluate the agreement of the two methods (food records and FFQ) at the category level | The inclusion of overly large portion sizes in the FFQ can be problematic, as infants around 12 months of age may taste a variety of foods without consuming real portions. |

| Nelson et al., 2002 [29] | US | NHANES | 1988–1994 | 1480 adults ≥ 17 years (640 males and 840 females) | To describe diet and exercise practices of U.S. adults with type 2 diabetes | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: calculate percentage of daily calories from total fat and saturated fat FFQ: create a combined variable for daily fruit and vegetable intake | The FFQ and 24-h recall data were self-reported. |

| Heller et al., 2001 [30] | US | NHANES | 1988–1944 | 19,668 participants aged ≥2 years | To investigate the associations between sugared soda consumption and caries | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: evaluate frequency and amount of sugared soda intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of sugared soda (12 years and older only) | The FFQ data relied on participant memory for the previous month’s diet and did not include food quantity information. The 24-h recall recorded only single-day data and there may have been recall bias (e.g., participants may have underestimated sugared soda consumption). |

| Smit et al., 2001 [31] | US | NHANES | 1988–1944 | 10,623 adults aged 20–59 years | To examine dietary intake and nutritional status of marijuana users and non-current marijuana users | One 24-h dietary recall | Qualitative FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of food (group) intake | The 24-h recall did not capture typical or individual intake and excluded supplements. The FFQ lacked quantitative nutrient details. |

| Song et al., 2000 [32] | US | NHANES | 1988–1944 | 27,378 participants ≥ 2 months (13,321 males and 14,057 females) | (1) To assess the nutritional significance of eggs in the American diet (2) To estimate the association between egg consumption and serum cholesterol concentration | One 24-h dietary recall | FFQ | 24-h dietary recall: estimate nutrient intake FFQ: evaluate frequency of egg intake | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okada, E.; Nakade, M.; Hanzawa, F.; Murakami, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Sasaki, S.; Takimoto, H. National Nutrition Surveys Applying Dietary Records or 24-h Dietary Recalls with Questionnaires: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4739. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224739

Okada E, Nakade M, Hanzawa F, Murakami K, Matsumoto M, Sasaki S, Takimoto H. National Nutrition Surveys Applying Dietary Records or 24-h Dietary Recalls with Questionnaires: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2023; 15(22):4739. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224739

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkada, Emiko, Makiko Nakade, Fumiaki Hanzawa, Kentaro Murakami, Mai Matsumoto, Satoshi Sasaki, and Hidemi Takimoto. 2023. "National Nutrition Surveys Applying Dietary Records or 24-h Dietary Recalls with Questionnaires: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 15, no. 22: 4739. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224739

APA StyleOkada, E., Nakade, M., Hanzawa, F., Murakami, K., Matsumoto, M., Sasaki, S., & Takimoto, H. (2023). National Nutrition Surveys Applying Dietary Records or 24-h Dietary Recalls with Questionnaires: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 15(22), 4739. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15224739