Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Indications/Items Reviewed on the Labels

2.2.1. Mandatory Food Information

- -

- The name of the food. The name of the food should be its legal name. In the absence of a legal name, the name of the food should be its customary name, and in the absence of such a name, a descriptive name should be used. The name of the food may not be replaced by the brand name.

- -

- The list of ingredients. The ingredients list should be headed by the word “Ingredients”. It should list all the ingredients of the food, in descending order of weight, as incorporated at the time of their use in the manufacture of the food, except for ingredients constituting less than 2%, which may appear after the other ingredients in a different order. These can be simple or compound ingredients, or additives, as regulated by Regulation 1333/2008 [31], and/or aromas, Regulation 1334/2008 [32].

- -

- The quantity of certain ingredients or categories of ingredients. The quantity should be expressed as a percentage and should appear on or adjacent to the sales description. If an ingredient appears in or is associated with the sales name, it should be prominently displayed on the labeling, either in words, pictures or graphic representations, as it is essential to distinguish the food from other foodstuffs or other foods. Substances that cause allergies/intolerances must be detailed in this list and should be highlighted. If vitamins and/or minerals appear in the list of ingredients, they are considered to be added and must follow the legislation that regulates them [33].

- -

- The net quantity of the food. It must be expressed in units of volume (liters, centiliters or milliliters) for liquid products or in units of weight (kilograms or grams) for other products. Where a package consists of one or more individual packages containing the same quantity of the same product, the net quantity should be given by indicating the net quantity of the individual package and the total number of packages.

- -

- The date of minimum durability or shelf life. If the date of minimum durability includes the indication of the day, it must be indicated with “best before…”; otherwise, it should be preceded by “best before the end of…”. The above indications must be accompanied by the date itself or a reference to the place where the date is indicated on the label. The indication of the date must be clear and in the following order: month and, where appropriate, year. If the duration of the food is less than three months, it is only necessary to indicate the day and the month; if the duration is more than three months but less than 18 months, it is sufficient to indicate the month and the year.

- -

- Special storage and/or use conditions. They must be indicated so that the consumer can store or use the food correctly, guaranteeing its minimum durability date.

- -

- The business’ name and address. The food business operator responsible for the food information should be the operator under whose name or business name the food is placed on the market or, if not established in the European Union, the importer of the food into the EU market.

- -

- The country of origin or place of provenance. The indication of the country of origin or provenance place should be mandatory where its omission is likely to mislead the consumer or where the information accompanying the food or the label as a whole may suggest that the food has a different country of origin.

- -

- Instructions for use, where necessary. Instructions for the use of a food should be provided where the absence of such instructions would hinder the correct use of the food by the consumer.

- -

- Nutritional claims. The mandatory nutritional information must include: energy values, amounts of fat, saturated fatty acids, carbohydrates, sugars, protein, and salt. Nutritional information should be expressed per 100 g or 100 mL. Vitamins and minerals should, in addition, be expressed as a percentage of the reference intakes. Where they appear, the statement “Reference intake for an average adult (8400 kJ/2000 kcal)” should be included adjacent to them. The portion or unit used should be indicated next to the nutritional information. The nutritional value and the nutrients mentioned should appear in the same field of view and should be presented together in a clear format and the prescribed order. If there is sufficient space, this information should be presented in a table format with the data in columns; if there is insufficient space, it should be presented in a linear format. It must appear in the main field of vision and a legible font size.

- -

- Modified atmosphere packaging. Where the shelf life of a food has been extended by packaging gases, it must contain this indication.

2.2.2. Voluntary Food Information

- -

- Nutritional and health claims [34]. A “nutritional claim” is any claim that states, suggests or implies that a food has specific beneficial nutritional properties due to: the energy (calorific value) it provides, whether reduced, increased, or not provided; or the nutrients or other substances it contains in reduced, increased or not provided proportions. Their function is to make consumers perceive that these foods have nutritional, physiological or other health benefits, and thus to trigger the decision to consume these products rather than others. A “health claim” is any claim that states, suggests, or implies that a relationship exists between a food category, a food or one of its constituents and health.

- -

- Lot [35]. A “lot” is defined as a set of sales units of a foodstuff produced, manufactured, or packaged under virtually identical circumstances. It should be determined by the producer, manufacturer, or packer of the product, or by the first seller established in the EU. The lot should be indicated by the letter “L”, except where it is clearly distinguishable from other indications on the label. The batch indication may be omitted if the date of minimum durability or the “use by” date contains at least the day and month.

- -

- Nominal quantity [36]. The nominal quantity is the mass (kilogram or gram) or volume (liter, centiliter, or milliliter) of the product marked on the container labeling, i.e., the quantity of product estimated to be contained in the package. These quantities must be easily legible, visible, and indelible. Where two or more packages form a multipack, the nominal quantities also apply to each individual package. The CE marking should be placed in the same field of vision as the indication of the nominal mass or volume, and it is represented by the symbol “℮”. The ℮-mark shows that a product complies with EU rules on the indication of the volume or weight and with the measuring methods to be used by the seller of packaged products.

3. Results

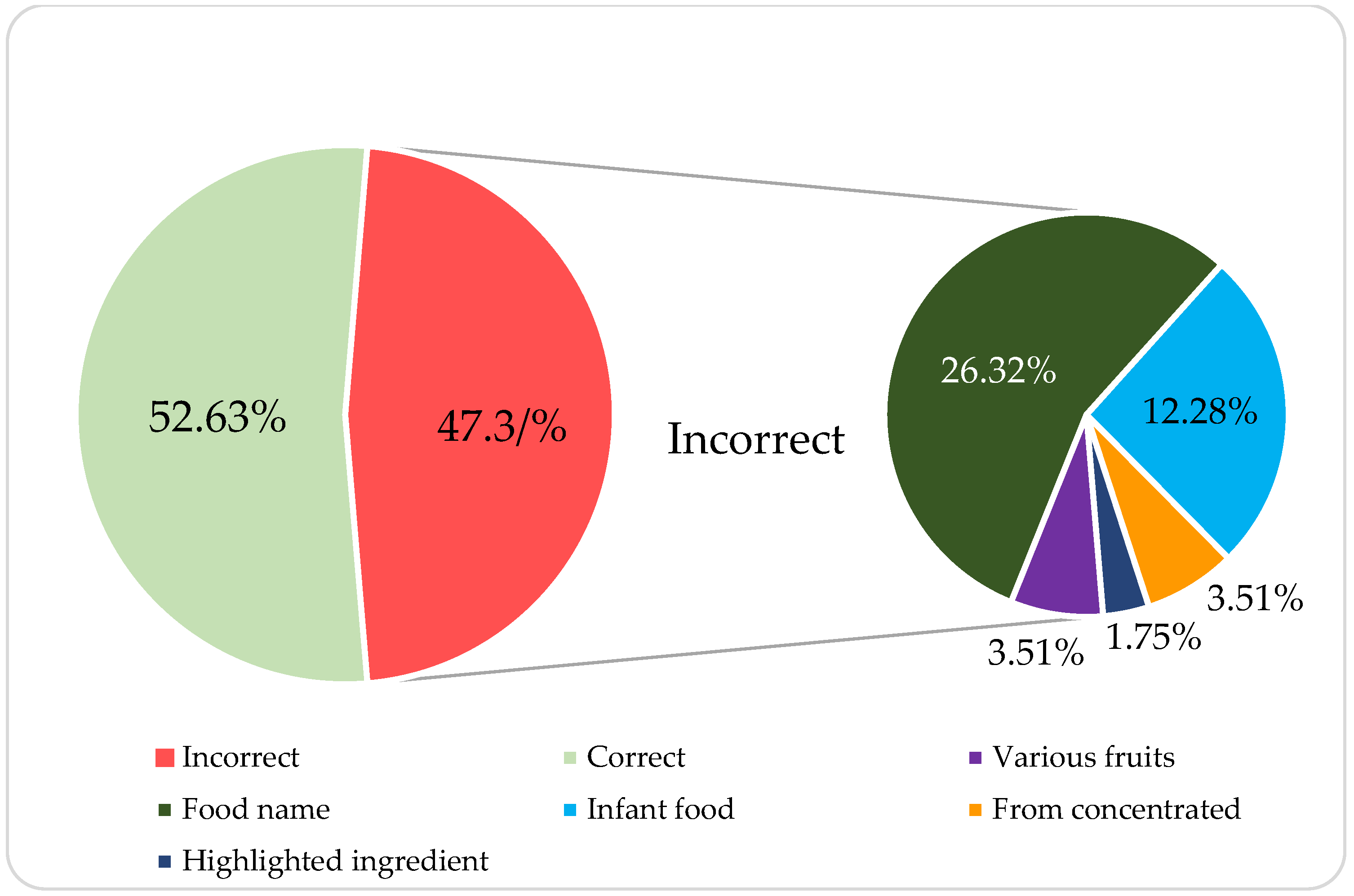

3.1. Mandatory Food Information Compliance

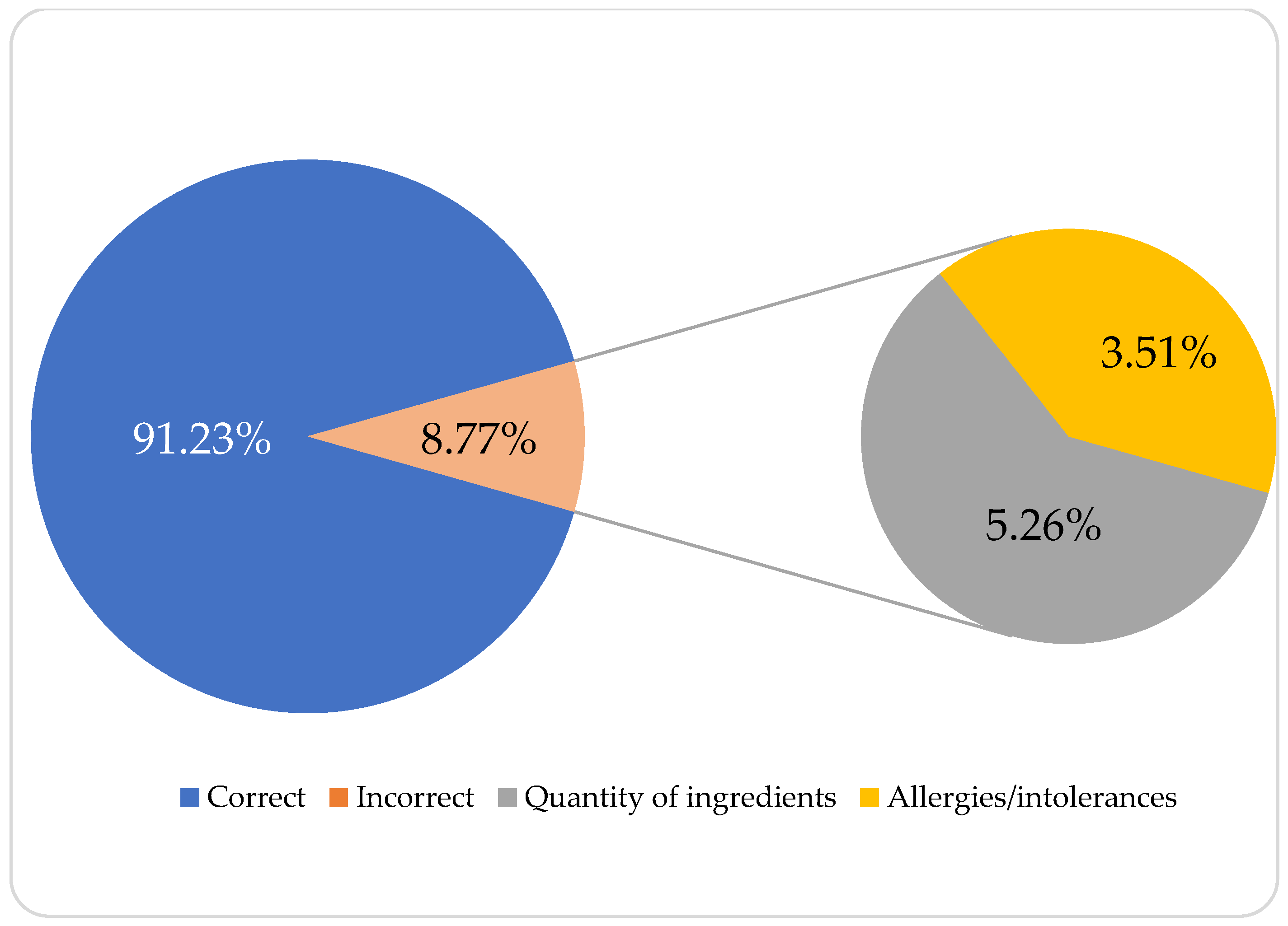

3.2. Voluntary Food Information Adequacy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tiwari, U. Production of fruit-based smoothies. In Fruit Juices. Extraction, Composition, Quality and Analysis; Rajauria, G., Tiwari, B.K., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cagno, R.; Minervini, G.; Rizzello, C.G.; de Angelis, M.; Gobbetti, M. Effect of lactic acid fermentation on antioxidant, texture, color and sensory properties of red and green smoothies. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FNS. FNS Document # SP40 CACFP17 SFSP17-2019, 23 September 2019. Smoothies Offered in Child Nutrition Programs. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/cn/smoothies-offered-child-nutrition-programs (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Pasvanka, K.; Varzakas, T.; Proestos, C. Minimally processed fresh green beverage industry (Smoothies, Shakes, Frappes, Pop Ups). In Minimally Processed Refrigerated Fruits and Vegetables. Food Engineering Series; Yildiz, F., Wiley, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassani, L.; Fiszman, S.; Álvarez, M.V.; Moreira, M.R.; Laguna, L.; Tarrega, A. Emotional response evoked when looking at and trying a new food product, measure throught images and works. A case-study with novel fruit and vegetables smoothies. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JA2020-0068; Japan Health Foods Market Overview. USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Ankara, Turkey, 2020.

- Dickinson, K.M.; Watson, M.S.; Prichard, I. Are clean eating blogs a source of healthy recipes? A comparative study of the nutrient composition of foods with and without clean eating claims. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, A.; Popa, M.E. Experimental research on active compounds and nutrients in new fruit smoothie products. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2019, 63, 51–59. Available online: http://horticulturejournal.usamv.ro/pdf/2019/issue_1/Art7.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Jaeger, S.R.; Giacalone, D. Barriers to consumption of plant-based beverages: A comparison of product users and non-users on emotional, conceptual, situational, conative and psychographic variables. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, M.A.; Costa, A.S.G.; Barreira, J.C.M.; Vinha, A.F.; Alves, R.C.; Rocha, A.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. How functional foods endure throughout the shelf storage? Effects of packing materials and formulation on the quality parameters and bioactivity of smoothies. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 65, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIJN (European Fruit Juice Association). Report 2018. Liquid Fruit Market Report. Available online: https://aijn.eu/files/attachments/.598/2018_Liquid_Fruit_Market_Report.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Derbyshire, E. Where are we with smoothies? A review of the latest guidelines, nutritional gaps and evidence. J. Nutr. Food. Sci. 2017, 7, 1000632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frestedt, J.L.; Young, L.R.; Bell, M. Meal replacement beverage twice a day in overweight and obese adults (MDRC2012-001). Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2012, 8, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cano-Lamadrid, M.; Tkacz, K.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Clemente-Villalba, J.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, L.; Lipan, L.; García-Garcá, E.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A.; Wojdylo, A. How a Spanish group of millennial generation perceives the commercial novel smoothies? Foods 2020, 9, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Guidance Fruit Juice, 1st ed.; British Soft Drinks Association: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.britishsoftdrinks.com/write/MediaUploads/Publications/BSDA_-_FRUIT_JUICE_GUIDANCE_May_2016.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Directive 2012/12/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 April 2012 amending Council Directive 2001/112/EC relating to fruit juices and certain similar products intended for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Union 2012, L 115, 1–11.

- Market Data Forecast. Europe Smoothie Market. 2023. Available online: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/europe-smoothies-market (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Oakes, M.E.; Slotterback, C.S. What’s in a name? A comparison of men’s and women’s judgements about food names and their nutrient contents. Appetite 2001, 36, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleton, K.M.; Pidgeon, H.J. 5-a-day fruit and vegetable food product labels: Reduced fruit and vegetable consumption following an exaggerated compared to a modest label. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiloglu, S. Authenticity and traceability in beverages. Food Chem. 2019, 277, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, C.; Johnson, H.; Curll, J. Consumer power to change the food system: A critical reading of food labels as governance spaces: The case of acai berry superfoods. J. Food Law Policy 2019, 15, 1. Available online: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp/vol15/iss1/1 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Gabriels, G.; Lambert, M. Nutritional supplement products: Does the label information influence purchasing decisions for the physically active? Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiaga, I.; Lamarca, M.; Jiménez, P.; Echevarria, G.; Leighton, F. Assessment of the reliability of food labeling in Chile. Rev. Med. Chile 2014, 142, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobstein, T.; Davies, S. Defining and labeling ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ food. Pub. Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Ferrarezi, A.; Olbrich dos Santos, K.; Monteiro, M. Critical assessment of the Brazilian regulations on fruit juices, with emphasis on ready-to-drink fruit juice. Rev. Nutr. 2010, 23, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, P.; Rueda-Robles, A.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, L.; Blanca-Herrera, R.M.; Quirantes-Piné, R.M.; Borrás-Linares, I.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Lozano-Sánchez, J. Analysis and Screening of Commercialized Protein Supplements for Sports Practice. Foods 2022, 11, 3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliza, R.; Macfie, H.; Hedderley, D. Use of computer-generated images and conjoint analysis to investigate sensory expectations. J. Sens. Stud. 2003, 18, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers. Off. J. Eur. Union 2011, L 304, 18–63.

- Real Decreto 2220/2004, 26th November, Regarding Allergies; BOE: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Real Decreto 1245/2008, 18th July, Modifies the Norm Related to Label, Presentation and Marketing of Food Products, Approved by RD 1334/1999; BOE: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Regulation 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L 354, 16–33.

- Regulation 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on flavourings and certain food ingredients with flavouring properties for use in and on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, L 354, 34–50.

- Regulation 1925/2006 on the addition of vitamins and minerals and of certain other substances to foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L 404, 26–38.

- Regulation 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Off. J. Eur. Union 2006, L 404, 9–25.

- Real Decreto 1808/1991, 13th December, Regulating the Indications or Marks Identifying the Lot to Which a Foodstuff Belongs; BOE: Beijing, China, 1991.

- Real Decreto 1801/2008, 3rd November, Laying Down Rules on Nominal Quantities for Prepacked Products and the Monitoring of Their Actual Contents; BOE: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Regulation 848/2018 on organic production and labeling of organic products and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L 150, 1–92.

- Dachner, N.; Mendelson, R.; Sacco, J.; Tarasuk, V. An examination of the nutrient content and on-package marketing of novel beverages. Appl. Phys. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 40, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkins, C.E.; Egan, B.; Peacock, M.; Klepacz, N.; Miklavec, K.; Pravst, I.; Pohar, J.; Garcia, A.; Groeppel-Klein, A.; Rayner, M.; et al. Understanding how consumers categorise health related claims on foods: A consumer-derived typology of health-related claims. Nutrients 2019, 11, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, V.; Green-Petersen, D.; Møgelvang-Hansen, P.; Bojesen Christensen, R.H.; Qvistgaard, F.; Hyldig, G. What’s (in) a real smoothie. A division of linguistic labour in consumers’ acceptance of name-product combinations? Appetite 2013, 63, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rørdam, M.O. EU Law on Food Naming: The Prohibition against Misleading Names in an Internal Market Context. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McCartney, D.; Rattray, M.; Desbrow, B.; Khalesi, S.; Irwin, C. Smoothies: Exploring the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of consumers and non-consumers. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 6, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 781/2013, 11th October, Regarding Fruit Juices to Human Consumption; BOE: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Yarar, N.; Orth, U.R. Consumer lay theories on healthy nutrition: A Q methodology application in Germany. Appetite 2018, 120, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsouri, E.; Zampelas, A.; Drosinos, E.H.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Labeling Assessment of Greek “Quality Label” Prepacked Cheeses as the Basis for a Branded Food Composition Database. Nutrients 2022, 14, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Calls on Countries to Reduce Sugars Intake among Adults and Children. 2015. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2015-who-calls-on-countries-to-reduce-sugars-intake-among-adults-and-children (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- FDA. What Are Added Sugars and How Are They Different from Total Sugars? 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/added-sugars-new-nutrition-facts-label (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- Rippe, J.M.; Sievenpiper, J.L.; Lê, K.A.; White, J.S.; Clemens, R.; Angelopoulos, T.J. What is the appropriate upper limit for added sugars consumption? Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, J.C.Y.; Moshtaghian, H.; Boylan, S.; Flood, V.M.; Rangan, A.M.; Barclay, A.W.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; Gill, T.P. A systematic methodology to estimate added sugar content of foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, M.N.; Braegger, C.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Domellöf, M.; Embleton, N.D.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Indrio, F.; Lapillonne, A.; et al. Sugar in infants, children and adolescents: A position paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, J.T.; L‘Abbé, M.R. Added sugars on nutrition labels: A way to support population health in Canada. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2016, 188, E373–E374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Moore, K.; Walker, D.; Laczniak, R. Attention mediates restrained eaters’ food consumption intentions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.R.B.; Rocha, K.F.; Carneiro, B.R.; Ribeiro, K.D.S.; Morais, I.L.; Breda, J.; Padrao, P.; Moreira, P. Nutritional adequacy of commercial food products targeted at 0-36-month-old children: A study in Brazil and Portugal. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 129, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, B.T.Y.; Irigaray, C.P.; Hillier, S.E.; Clegg, M.E. The sugar content of children’s and lunchbox beverages sold in the UK before and after the soft drink industry levy. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 598–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, J.; Hashem, K.M.; Jenner, K.H.; Lloyd-Willimas, F.; Bromley, H.; Capewell, S. How much sugar is hidden in drinks marketed to children? A survey of fruit juices, juice drinks and smoothies. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, P.; Fiszman, S.M. Exploring consumers’ knowledge and perceptions of hydrocolloids used as food additives and ingredients. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 30, 477–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.; Zasadzinski, L.; Zhu, L.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Assessing consumers’ understanding of the term “Natural” on food labeling. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1891–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrarezi, A.; dos Santos, K.O.; Monteiro, M. Consumer interpretation of ready to drink orange juice and nectar labeling. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 48, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plasek, B.; Lakner, Z.; Temesi, Á. I believe it is healthy—Impact of extrinsic product attributes in demonstrating healthiness of functional food products. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruhn, C.; Feng, Y. Exploring consumer response to labeling a processing aid that enhances food safety. Food Prot. Trends 2021, 41, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skypala, I.J. Can patients with oral allergy syndrome be at risk of anaphylaxis? Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Inmunol. 2020, 20, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, M.J.; Koeberl, M.; Hedges, C.E.; Biros, E.; Ruethers, T.; Clarke, D. Undeclared allergens in imported packaged food for retail in Australia. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal de Sousa, T.; Pinheiro da Silva, J.; Ribeiro Lodete, A.; Silva Lima, D.; Alvez Mesquita, A.; Borges de Almedida, A.; Rocha Placido, G.; Buranelo Egea, M. Vitamin C, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Brazilian baby foods. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 51, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, E.; Weiss, C.C.; Furlong, T.J.; Sicherer, S.H. Impact of ingredient labeling practices on food allergic consumers. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005, 95, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, J.; Langen, N.; Hecht, S.; Hartmann, M. Sustainability as sales argument in the fruit juice industry? An analysis of on-product communication. Int. J. Food Syst. Dynam. 2014, 5, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbroek, M.M. Organic Look, Healthier Product? An Experimental Study on the Influence of Organic Illustrations and Typeface on the Perceived Healthiness, Taste Expectation and Purchase Intention. Master’s Thesis, University of Twente, Enschede, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, C.F.F.; Lopes, M.L.M.; Valente-Mesquita, V.L. Storage impact on the antioxidant activity and ascorbic acid level of mandarin juices and drinks. Rev. Nutr. 2012, 25, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abountiolas, M.; Nunes, C.N. Polyphenols, ascorbic acid and antioxidant capacity of commercial nutritional drinks, fruit juices, smoothies and tea. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanemura, N.; Machii, Y.; Urushihara, H. The first survey of gap between the actual labeling and efficacy information of functional substances in food under the regulatory processes in Japan. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godden, E.; Thornton, L.; Avramova, Y.; Dens, N. High hopes for front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition labels? A conjoint analysis on the trade-offs between a FOP label, nutrition claims, brand and price for different consumer segments. Appetite 2023, 180, 106356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goiana-da-Silva, F.; Cruz-e-Silva, D.; Nobre-da-Costa, C.; Nunes, A.M.; Fialon, M.; Egnell, M.; Galan, P.; Julia, C.; Talati, Z.; Pettigrew, S.; et al. Nutri-Score: The Most Efficient Front-of-Pack Nutrition Label to Inform Portuguese Consumers on the Nutritional Quality of Foods and Help Them Identify Healthier Options in Purchasing Situations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Smoothie Code | Main Ingredients | Number of Samples | Group of Smoothies |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | Fruits | 29 | F1 to F29 |

| FV | Fruits and vegetables | 6 | FV1 to FV6 |

| FD | Fruits and dairy products | 4 | FD1 to FD4 |

| FVD | Fruits, vegetables and dairy products | 2 | FVD1 to FVD2 |

| FC | Fruits and cereals | 6 | FC1 to FC6 |

| FVC | Fruits, vegetables and cereals | 2 | FVC1 to FVC2 |

| FCD | Fruits, cereals and dairy products | 5 | FCD1 to FCD5 |

| FVCD | Fruits, vegetables, cereals and dairy products | 3 | FVCD1 to FVCD3 |

| Regulated | Not Regulated/Other Information |

|---|---|

| Nutritional and health claims [34] | Nutritional and health claims |

| Lot [35] | Brand and highlighted ingredients |

| Nominal quantity [36] | Bar code |

| Suitable for vegans [28] | Recycling pictograms |

| Organic production [37] | Presentation images |

| Business/operator contact | |

| Age recommended | |

| Color combinations |

| Indication or Item | Smoothie Types and Number per Type | Total Errors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F 29 | FV 6 | FD 4 | FVD 2 | FC 6 | FVC 2 | FCD 5 | FVCD 3 | |||

| Food name | 13/29 | 4/6 | 1/4 | 2/2 | 3/6 | 1/2 | 1/5 | 2/3 | 27/57 | |

| Ingredients list | Simple ingredients | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 0/54 |

| Additives | 0/7 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 1/15 | |||

| Aromas | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/10 | |||||

| Compound ingredients | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/4 | |||||||

| Quantity of certain ingredients | 2/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 2/57 | |

| Allergens/ intolerances | 1/3 | 1/1 | 0/3 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 2/15 | ||||

| Vitamins/ minerals | 0/18 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/29 | ||

| Net quantity | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 1/3 | 1/57 | |

| Shelf life | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 0/57 | |

| Conservation/use | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/2 | 0/56 | |

| Business name and address | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 0/57 | |

| Origin country * | 0/57 | |||||||||

| Instructions for use | 0/19 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/35 | ||

| Nutritional claims | 16/29 | 3/6 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 4/6 | 2/2 | 0/5 | 1/3 | 26/55 | |

| Modified atmosphere packaging | 0/15 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/28 | |||

| Total error/smoothie type | 31 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 59 | |

| Claim or Item | Smoothie Types and Number per Type | Total Errors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F 29 | FV 6 | FD 4 | FVD 2 | FC 6 | FVC 2 | FCD 5 | FVCD 3 | ||

| Without added sugars or 0% added sugars | 0/21 | 0/4 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/5 | 0/0 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/36 |

| Without preservatives | 0/12 | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/19 | |||

| Without colorants | 0/8 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/14 | ||

| Without artificial aromas | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/2 | ||||||

| 100% natural | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 1/7 | ||||

| % fruit | 0/18 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/26 | |||

| Bio, eco | 0/8 | 0/4 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/21 |

| Source of vitamin C or with vitamin C | 4/11 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/3 | 1/1 | 8/17 | |||

| Source of fiber | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | ||||||

| Rich in calcium, source of calcium or with calcium | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/3 | ||||||

| Without gluten | 0/18 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/35 |

| Without lactose | 0/6 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/11 | |||

| Without milk, powdered milk or added cream | 0/3 | 0/1 | 0/4 | ||||||

| Without palm oil | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/6 | ||||

| Antioxidant, detox, relaxing or energetic | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 4/4 | |||||

| Lot | 0/29 | 0/6 | 0/4 | 0/2 | 0/6 | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/3 | 0/59 |

| Nominal quantity | 0/3 | 0/2 | 0/5 | ||||||

| Total error/smoothie type | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Da Silva-Mojón, L.; Pérez-Lamela, C.; Falqué-López, E. Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation? Nutrients 2023, 15, 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204426

Da Silva-Mojón L, Pérez-Lamela C, Falqué-López E. Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation? Nutrients. 2023; 15(20):4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204426

Chicago/Turabian StyleDa Silva-Mojón, Lorena, Concepción Pérez-Lamela, and Elena Falqué-López. 2023. "Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation?" Nutrients 15, no. 20: 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204426

APA StyleDa Silva-Mojón, L., Pérez-Lamela, C., & Falqué-López, E. (2023). Smoothies Marketed in Spain: Are They Complying with Labeling Legislation? Nutrients, 15(20), 4426. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204426