A Pilot Goal-Oriented Episodic Future Thinking Weight Loss Intervention for Low-Income Overweight or Obese Young Mothers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

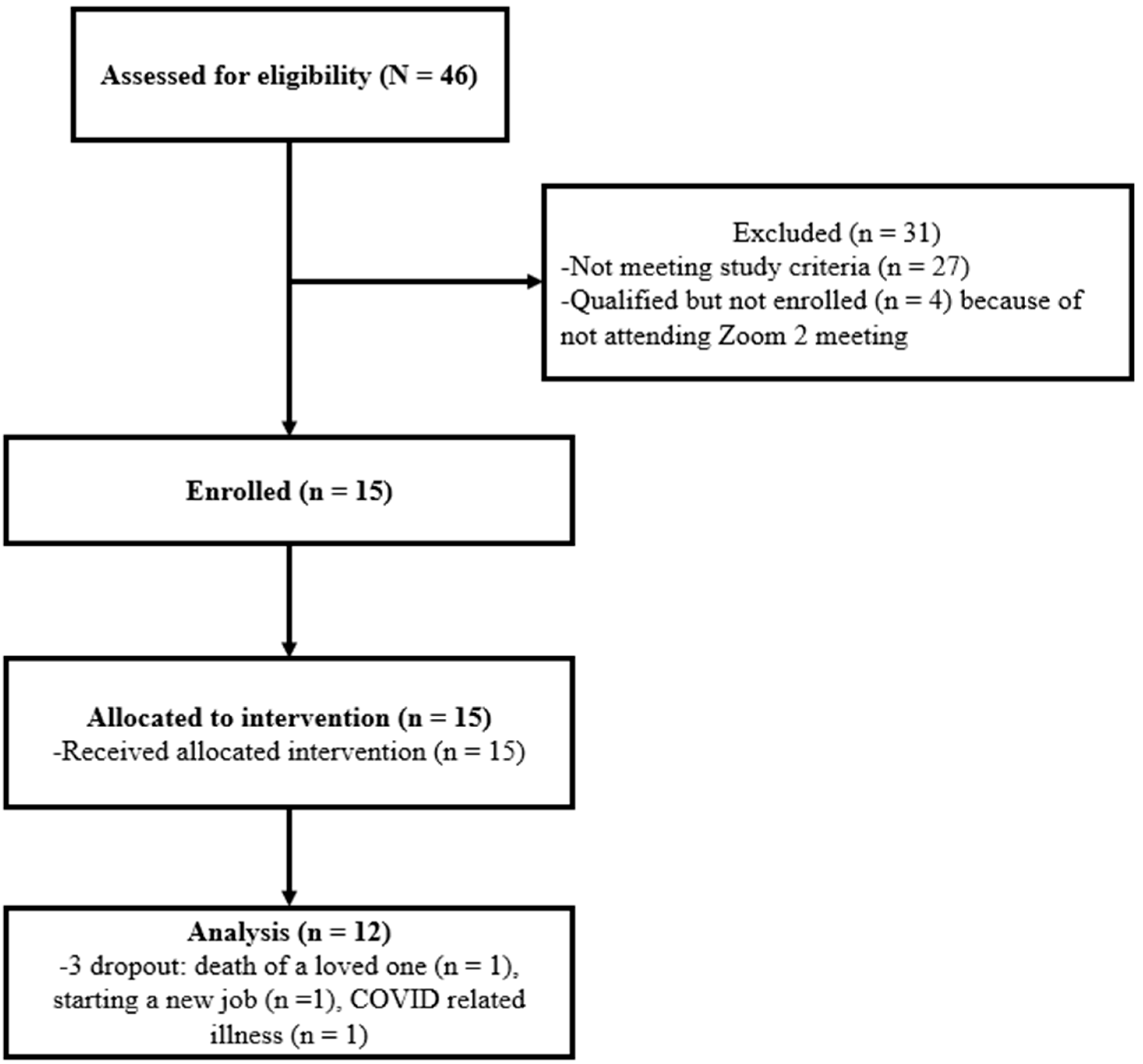

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Intervention: Web-Based Intervention and Online Health Coaching

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Intervention Adherence

3.2. Acceptability of Intervention

3.3. Intervention Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014, 311, 806–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.P.; Gavard, J.A.; Rice, J.J.; Catanzaro, R.B.; Artal, R.; Hopkins, S.A. The impact of interpregnancy weight change on birthweight in obese women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 208, 205.e1–205.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Villamor, E.; Altman, M.; Bonamy, A.K.; Granath, F.; Cnattingius, S. Maternal overweight and obesity in early pregnancy and risk of infant mortality: A population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ 2014, 349, g6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.F.; Abell, S.K.; Ranasinha, S.; Misso, M.; Boyle, J.A.; Black, M.H.; Li, N.; Hu, G.; Corrado, F.; Rode, L.; et al. Association of Gestational Weight Gain with Maternal and Infant Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2017, 317, 2207–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshberg, A.; Srinivas, S.K. Epidemiology of maternal morbidity and mortality. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, J.; Berg, M.; Dencker, A.; Olander, E.K.; Begley, C. Risks associated with obesity in pregnancy, for the mother and baby: A systematic review of reviews. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 621–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Voerman, E.; Amiano, P.; Barros, H.; Beilin, L.J.; Bergström, A.; Charles, M.A.; Chatzi, L.; Chevrier, C.; Chrousos, G.P.; et al. Impact of maternal body mass index and gestational weight gain on pregnancy complications: An individual participant data meta-analysis of European, North American and Australian cohorts. BJOG 2019, 126, 984–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, L.K.; Straub, H.; McKinney, C.; Plunkett, B.; Minkovitz, C.S.; Schetter, C.D.; Ramey, S.; Wang, C.; Hobel, C.; Raju, T.; et al. Postpartum weight retention risk factors and relationship to obesity at 1 year. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 125, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkley, A.J.; Bodicoat, D.H.; Greaves, C.J.; Russell, C.; Yates, T.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K. Diabetes prevention in the real world: Effectiveness of pragmatic lifestyle interventions for the prevention of type 2 diabetes and of the impact of adherence to guideline recommendations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi-Sunyer, X.; Blackburn, G.; Brancati, F.L.; Bray, G.A.; Bright, R.; Clark, J.M.; Curtis, J.M.; Espeland, M.A.; Foreyt, J.P.; Graves, K.; et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: One-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 2007, 30, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettens, K.M.; Gorin, A.A. Executive function in weight loss and weight loss maintenance: A conceptual review and novel neuropsychological model of weight control. J. Behav. Med. 2017, 40, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alick, C.L.; Samuel-Hodge, C.; Ammerman, A.; Ellis, K.R.; Rini, C.; Tate, D.F. Motivating Weight Loss Among Black Adults in Relationships: Recommendations for Weight Loss Interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2023, 50, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, S.A.; Lange, K.; Ramos, A.; Thamotharan, S.; Rassu, F. The relationship between stress and delay discounting: A meta-analytic review. Behav. Pharmacol. 2014, 25, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraven, M.; Baumeister, R.F. Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle? Psychol. Bull. 2000, 126, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izard, C. The Many Meanings/Aspects of Emotion: Definitions, Functions, Activation, and Regulation. Emot. Rev. 2010, 2, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.N.; Markland, D.; Carraca, E.V.; Vieira, P.N.; Coutinho, S.R.; Minderico, C.S.; Matos, M.G.; Sardinha, L.B.; Teixeira, P.J. Exercise autonomous motivation predicts 3-yr weight loss in women. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2011, 43, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.; Mata, J.; Silva, M.N.; Sardinha, L.B.; Teixeira, P.J. Predicting long-term weight loss maintenance in previously overweight women: A signal detection approach. Obesity 2015, 23, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraca, E.V.; Marques, M.M.; Rutter, H.; Oppert, J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Lakerveld, J.; Brug, J. Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: A systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Silva, M.N.; Mata, J.; Palmeira, A.L.; Markland, D. Motivation, self-determination, and long-term weight control. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, S.; Norman, P.; Breeze, P.; Brennan, A.; Ahern, A.L. Mechanisms of Action in a Behavioral Weight-Management Program: Latent Growth Curve Analysis. Ann. Behav. Med. 2022, 56, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.; Daniel, T.O.; Epstein, L.H. Does goal relevant episodic future thinking amplify the effect on delay discounting? Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 51, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, T.O.; Stanton, C.M.; Epstein, L.H. The future is now: Comparing the effect of episodic future thinking on impulsivity in lean and obese individuals. Appetite 2013, 71, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dassen, F.C.; Jansen, A.; Nederkoorn, C.; Houben, K. Focus on the future: Episodic future thinking reduces discount rate and snacking. Appetite 2016, 96, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, L.R.; Chen, W.H.; Reily, N.M.; Castel, A.D. The parallel impact of episodic memory and episodic future thinking on food intake. Appetite 2016, 101, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sze, Y.Y.; Daniel, T.O.; Kilanowski, C.K.; Collins, R.L.; Epstein, L.H. Web-Based and Mobile Delivery of an Episodic Future Thinking Intervention for Overweight and Obese Families: A Feasibility Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015, 3, e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, R.G.; Gilbert, S.J.; Burgess, P.W. A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6771–6779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atance, C.M.; O’Neill, D.K. Episodic future thinking. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2001, 5, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, D.; Kay, M.; Burroughs, J.; Svetkey, L.P.; Bennett, G.G. The Effect of a Digital Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention on Adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Dietary Pattern in Medically Vulnerable Primary Care Patients: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calugi, S.; Marchesini, G.; El Ghoch, M.; Gavasso, I.; Dalle Grave, R. The association between weight maintenance and session-by-session diet adherence, weight loss and weight-loss satisfaction. Eat. Weight. Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2020, 25, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, D.L.; Addis, D.R.; Buckner, R.L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: The prospective brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, D.; D’Argembeau, A. Neural correlates of personal goal processing during episodic future thinking and mind-wandering: An ALE meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36, 2928–2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, R.G.; Schacter, D.L. Specifying the core network supporting episodic simulation and episodic memory by activation likelihood estimation. Neuropsychologia 2015, 75, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, H.; Taki, Y.; Sassa, Y.; Hashizume, H.; Sekiguchi, A.; Fukushima, A.; Kawashima, R. Brain structures associated with executive functions during everyday events in a non-clinical sample. Brain Struct. Funct. 2013, 218, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, D.L.; Benoit, R.G.; Szpunar, K.K. Episodic Future Thinking: Mechanisms and Functions. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 17, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palombo, D.J.; Hayes, S.M.; Peterson, K.M.; Keane, M.M.; Verfaellie, M. Medial Temporal Lobe Contributions to Episodic Future Thinking: Scene Construction or Future Projection? Cereb. Cortex 2018, 28, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Buchel, C. Episodic future thinking reduces reward delay discounting through an enhancement of prefrontal-mediotemporal interactions. Neuron 2010, 66, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Tan, A.; Schaffir, J.; Wegener, T.D.; Worly, B.; Strafford, K.; Soma, L.; Sampsell, C.; Rosen, M. A Pilot Lifestyle Behavior Intervention for Overweight or Obese Pregnant Women: Results and Process Evaluation. J. Pediatr. Perinatol. Child Health 2023, 7, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Brown, R.; Nitzke, S. Results and lessons learned from a prevention of weight gain program for low-income overweight and obese young mothers: Mothers In Motion. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Brown, R.; Nitzke, S. A Community-Based Intervention Program’s Effects on Dietary Intake Behaviors. Obesity 2017, 25, 2055–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Pek, J.; Wegener, D.T.; Sherman, J.P. Lifestyle Behavior Intervention Effect on Physical Activity in Low-Income Overweight or Obese Mothers of Young Children. J. Pediatr. Perinatol. Child Health 2022, 6, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.W.; Nitzke, S.; Brown, R. Mothers In Motion intervention effect on psychosocial health in young, low-income women with overweight or obesity. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.; Rennie, L.; Uskul, A.K.; Appleton, K.M. Visualising future behaviour: Effects for snacking on biscuit bars, but no effects for snacking on fruit. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percent Energy from Fat Screener. Available online: http://riskfactors.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fat (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Percentage Energy from Fat Screener: Scoring Procedures. Available online: https://epi.grants.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fat/scoring.html#recen (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Protocol—Sugar Intake (Added). Available online: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/51001 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Protocol—Fruits and Vegetables Intake. Available online: https://www.phenxtoolkit.org/protocols/view/50701?origin=domain (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, L.G.; Tuson, K.M.; Haddad, N.K. Client Motivation for Therapy Scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. J. Pers. Assess. 1997, 68, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Nitzke, S.; Brown, R.; Baumann, L.; Oakley, L. Development and validation of a self-efficacy measure for fat intake behaviors of low-income women. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2003, 35, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Brown, R.; Nitzke, S. Scale development: Factors affecting diet, exercise, and stress management (FADESM). BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studies. J. Psychol. 2005, 139, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, A.J.; Witkowsky, P. Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview. In Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Qualitative Data Analysis; Vanover, C., Mihas, P., Saldaña, J., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- D’Argembeau, A.; Stawarczyk, D.; Majerus, S.; Collette, F.; Van der Linden, M.; Feyers, D.; Maquet, P.; Salmon, E. The neural basis of personal goal processing when envisioning future events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010, 22, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Wegener, D.; Tan, A.; Schaffir, J.; Worly, B.; Strafford, K.; Soma, L.; Sampsell, C. Pilot Lifestyle Intervention Effect on Lifestyle Behaviors, Psychosocial Factors, and Affect. J. Pediatr. Perinatol. Child Health 2023, 7, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, M.D.; Barr, M.L.; Charlier, C.M.; Famodu, O.A.; Zhou, W.; Mathews, A.E.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Colby, S.E. Self-Reported vs. Measured Height, Weight, and BMI in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, S.E.; Lagerros, Y.T.; Bälter, K. How valid are Web-based self-reports of weight? J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beleigoli, A.; Andrade, A.; Diniz, M.; Alvares, R.; Ferreira, M.; Silva, L.; Rodrigues, M.; Jacomassi, L.; Cerqueira, A.; Ribeiro, A. Validation of Anthropometric Measures Self-Reported in a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Based Platform for Weight Loss. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2019, 266, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenténius, E.; Andersson-Assarsson, J.C.; Carlsson, L.M.S.; Svensson, P.A.; Larsson, I. Self-Reported Weight-Loss Methods and Weight Change: Ten-Year Analysis in the Swedish Obese Subjects Study Control Group. Obesity 2018, 26, 1137–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklas, J.M.; Huskey, K.W.; Davis, R.B.; Wee, C.C. Successful weight loss among obese U.S. adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobile Facat Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

Think about the second part about choosing a weekly goal from the list we provided (refer to pre-written goal)

|

| Remember the 5Ws (WHAT, WHY, WHERE, WHEN, WHO) and H (HOW). Tell me three things you liked most about that part of the program (Probe: give me some examples, be more specific, tell me more, and in what way. Why?). |

Tell me three things you liked least about the 5Ws and H. (Probe: give me some examples, be more specific, tell me more, and in what way. Why?).

|

Let’s talk about the self-care booster (refer to goal progress evaluation)

|

| How has joining the program affected other areas of your life? (if needed) For example, have you found yourself making more plans in other areas of your life? (Probe: give me some examples, be more specific, tell me more, and in what why. What has been helpful or not helpful and why?) |

| Common Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Helpfulness of Pre-written goals | “Whoever conducted this research study has really put tremendous thought into each goal. It (the pre-written goal) definitely gave me a boost of confidence afterwards… made me like ‘Okay, these are my goals for the week; this is how I’m going to accomplish it”. “I’ve never had to think about my goal and writing… I would just think about in my head…I think it was more useful to see it and writing it because it made it more concrete more real”. “It was a built-in-accountability tool, so that I couldn’t just think about maybe I want to change this, or maybe I want to meal plan or maybe”. |

| Usefulness of applying 5Ws and HOW to make plans for accomplishing goals | “It (5Ws and How) made me think of an actual plan, not just …like oh I’m going to work out, but instead… okay when, how, who am I going to be with, where, and that was really helpful to visualize how I’m going to do something and then, once I did, that it was easier to actually put into practice”. |

| Helpfulness of example plans | “I liked that they had very concreate examples of how other women have overcome certain challenges that I’m facing specifically related to like positive self-talk and managing stress”. |

| Benefits for engaging in goal progress evaluation | “I thought it was good, because it gave me a chance to think about did I actually do the things I wanted to do and the process of how the week went when I was trying to accomplish those goals”. |

| Increasing motivation to implement plans through GoEFT | “that visualization was really helpful for me” “I like picturing what I wanted and like actually putting it down on paper …this is what I want now, how do I get there, what are the things that I want to do to get there, who like it, it made me think more elaborate about the dream and the things that I want to accomplish in my life” “the most helpful thing …that I’ll definitely carry with me after this (after completing the intervention)”. “I’m picturing the outcomes that I wanted and picturing my family happy and healthy because that’s really the important part”. “mental picture idea that will definitely stick with me and may be useful for a very long time” “I shared the picturing how things go if things went wrong…with my husband and he found it helpful. He was really stressed about something and I like broken down…what the worst things that can happen…what can we do to not make that happen, how we react... that really helped us get through... I found that really helpful”. |

| Positive intervention impact on children, confidence, and mental health | “It (the intervention) made me think more of me versus always being in mommy mode thinking about us (her and her children). …I can focus more on me and my emotions and how to fix things. I don’t get quite as grumpy and upset with my kids as I did for a while, which is good”. Things are more manageable than I was thinking and that just a little bit of positive self-talk really changes, a whole life” “the positive self talk that’s change, which is tremendously helped my mental tremendously once my mental is good and the rest of the day, seems to go smoothly”. “my response to expectations, not being as hard on myself if I don’t meet goals” “Change the way I think about myself… improved my self-esteem,… I am really happy... I’m also like the steps where it’s like happy healthy family thinking of a happy healthy family and then think about like the pros and cons of. If I continue the cons of if I continued being sad, stress, you know, whatever versus just change it and being happy healthy so that has been really awesome I have also taken that to heart and its really changed my outlook on stressful things because instead of like taking it and then just making it bigger and worse and like drowning I can kind of distance myself and say, yes, it’s stressful but its okay I’m still I’m okay”. |

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Cohen’s D | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight (lbs) | ||||||

| T1 | 194.1 | 38.04 | 169.9 | 218.3 | ||

| T2 | 191.2 | 37.70 | 167.2 | 215.1 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | −2.92 | 4.23 | −5.60 | −0.23 | −0.69 | 0.036 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| T1 | 32.14 | 5.23 | 28.81 | 35.46 | ||

| T2 | 31.58 | 5.20 | 28.27 | 34.89 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | −0.56 | 0.73 | −1.02 | −0.10 | −0.77 | 0.022 |

| Percentage Energy from Fat | ||||||

| T1 | 34.59 | 4.93 | 31.46 | 37.72 | ||

| T2 | 31.17 | 5.06 | 27.96 | 34.39 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | −3.42 | 6.72 | −7.69 | 0.85 | −0.51 | 0.106 |

| Added Sugar (tsp) | ||||||

| T1 | 21.07 | 14.88 | 11.61 | 30.53 | ||

| T2 | 12.53 | 8.32 | 7.24 | 17.82 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | −8.54 | 17.88 | −19.9 | 2.82 | −0.48 | 0.126 |

| Fruit/Veg (Cup, Including French Fries) | ||||||

| T1 | 4.87 | 3.42 | 2.57 | 7.16 | ||

| T2 | 5.72 | 3.43 | 3.41 | 8.02 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 0.85 | 1.75 | −0.32 | 2.03 | 0.49 | 0.138 |

| Fruit/Veg (Cup, Excluding French Fries) | ||||||

| T1 | 4.73 | 3.42 | 2.44 | 7.03 | ||

| T2 | 5.55 | 3.45 | 3.24 | 7.87 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 0.82 | 1.82 | −0.41 | 2.04 | 0.45 | 0.168 |

| Physical Activity (Weekly MET) | ||||||

| T1 | 107.0 | 249.6 | −51.6 | 265.6 | ||

| T2 | 171.5 | 390.0 | −76.4 | 419.3 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 64.46 | 504.1 | −256 | 384.7 | 0.13 | 0.6664 |

| Perceived Stress | ||||||

| T1 | 18.33 | 6.10 | 14.46 | 22.21 | ||

| T2 | 14.67 | 6.64 | 10.45 | 18.88 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | −3.67 | 7.01 | −8.12 | 0.79 | −0.52 | 0.097 |

| Emotion Control (Total Score) | ||||||

| T1 | 38.50 | 8.34 | 33.20 | 43.80 | ||

| T2 | 42.58 | 10.61 | 35.84 | 49.33 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 4.08 | 5.74 | 0.43 | 7.73 | 0.71 | 0.032 |

| Autonomous Motivation: Healthy Eating | ||||||

| T1 | 37.58 | 4.01 | 35.04 | 40.13 | ||

| T2 | 40.25 | 3.22 | 38.20 | 42.30 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 2.67 | 3.58 | 0.39 | 4.94 | 0.75 | 0.025 |

| Autonomous Motivation: Physical Activity | ||||||

| T1 | 36.00 | 5.72 | 32.37 | 39.63 | ||

| T2 | 40.50 | 2.71 | 38.78 | 42.22 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 4.50 | 5.79 | 0.82 | 8.18 | 0.78 | 0.021 |

| Autonomous Motivation: Stress Management | ||||||

| T1 | 36.50 | 4.87 | 33.41 | 39.59 | ||

| T2 | 40.00 | 2.83 | 38.20 | 41.80 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 3.50 | 3.97 | 0.98 | 6.02 | 0.88 | 0.011 |

| Self-Efficacy: Healthy Eating | ||||||

| T1 | 19.83 | 4.90 | 16.72 | 22.94 | ||

| T2 | 22.25 | 4.88 | 19.15 | 25.35 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 2.42 | 3.96 | −0.10 | 4.94 | 0.61 | 0.058 |

| Self-Efficacy: Physical Activity | ||||||

| T1 | 25.33 | 7.18 | 20.77 | 29.89 | ||

| T2 | 29.17 | 7.41 | 24.46 | 33.87 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 3.83 | 8.39 | −1.50 | 9.16 | 0.46 | 0.142 |

| General Self-Efficacy | ||||||

| T1 | 31.42 | 5.18 | 28.13 | 34.71 | ||

| T2 | 34.83 | 4.24 | 32.14 | 37.53 | ||

| T2 vs. T1 | 3.42 | 5.88 | −0.32 | 7.16 | 0.58 | 0.069 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, M.-W.; Tan, A.; Wegener, D.T.; Lee, R.E. A Pilot Goal-Oriented Episodic Future Thinking Weight Loss Intervention for Low-Income Overweight or Obese Young Mothers. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133023

Chang M-W, Tan A, Wegener DT, Lee RE. A Pilot Goal-Oriented Episodic Future Thinking Weight Loss Intervention for Low-Income Overweight or Obese Young Mothers. Nutrients. 2023; 15(13):3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133023

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Mei-Wei, Alai Tan, Duane T. Wegener, and Rebecca E. Lee. 2023. "A Pilot Goal-Oriented Episodic Future Thinking Weight Loss Intervention for Low-Income Overweight or Obese Young Mothers" Nutrients 15, no. 13: 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133023

APA StyleChang, M.-W., Tan, A., Wegener, D. T., & Lee, R. E. (2023). A Pilot Goal-Oriented Episodic Future Thinking Weight Loss Intervention for Low-Income Overweight or Obese Young Mothers. Nutrients, 15(13), 3023. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15133023