Perceptions and Experiences of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants Related to Receiving Food and Nutrition-Related Text Messages Sent Agency-Wide: Findings from Focus Groups in San Diego County, California

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Intervention

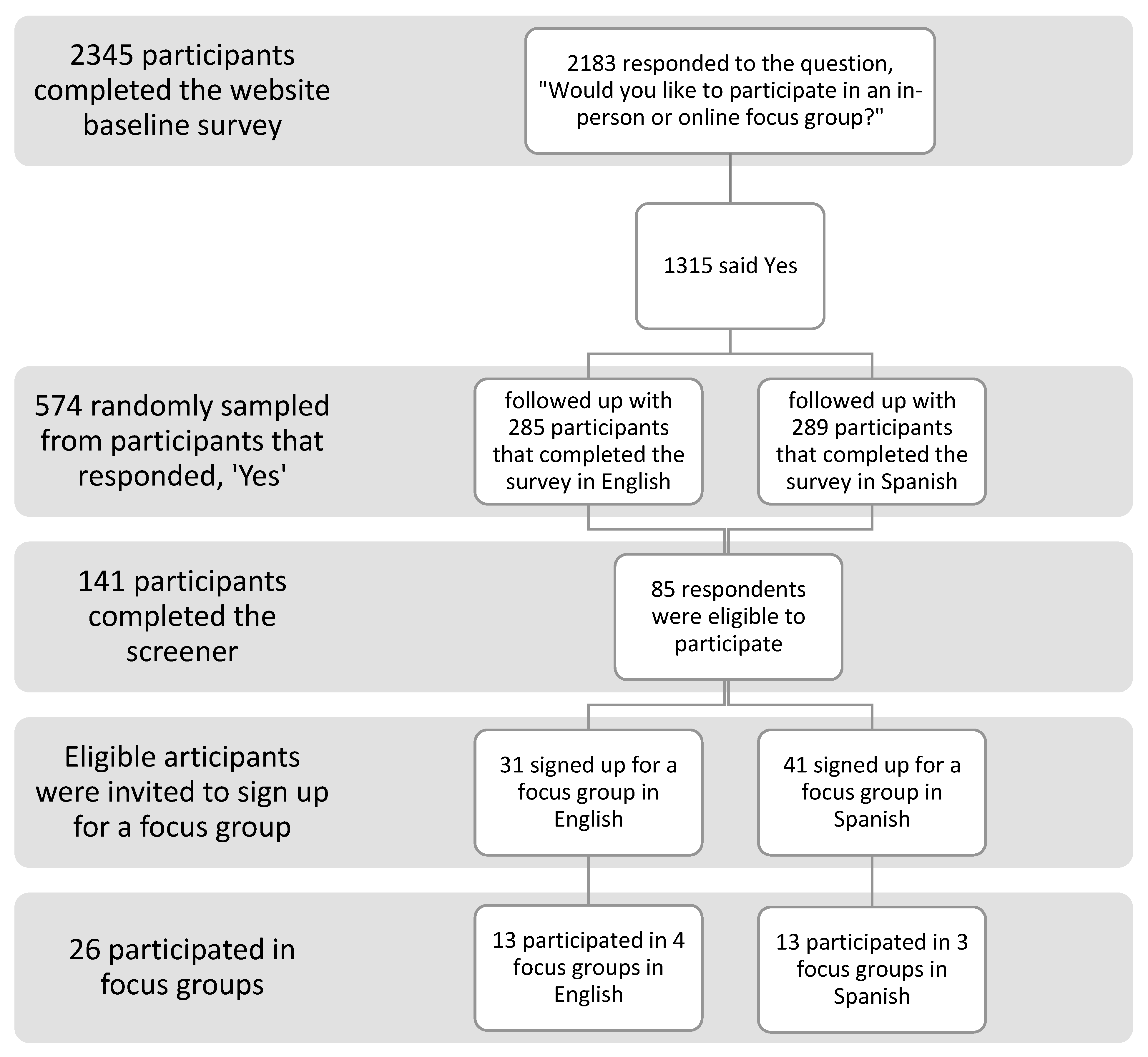

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. Focus Groups

2.4. Analysis

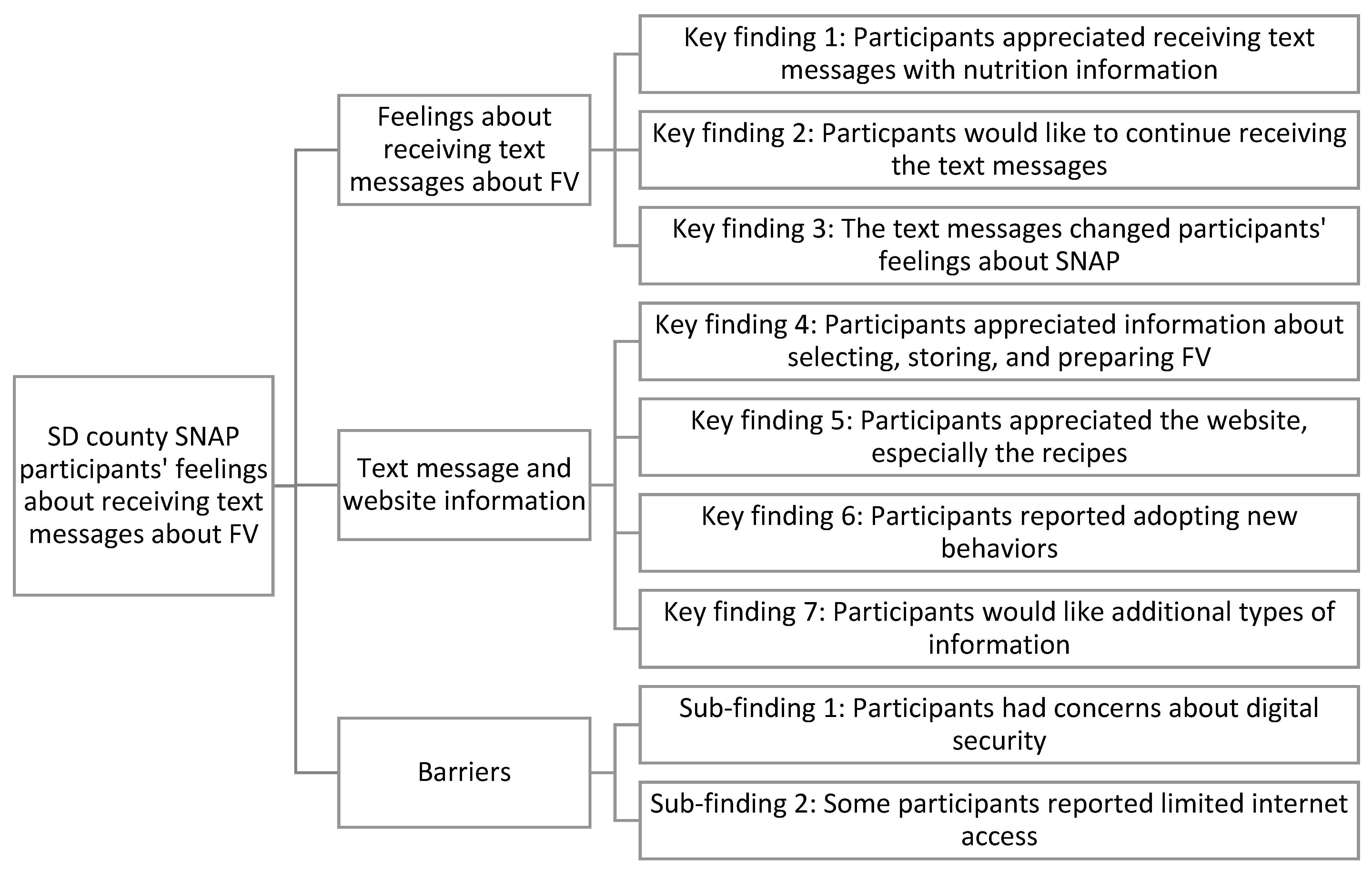

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- American Heart Association News. Cardiovascular Diseases Affect Nearly Half of American Adults, Statistics Show. Available online: https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/01/31/cardiovascular-diseases-affect-nearly-half-of-american-adults-statistics-show (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Wallace, T.C.; Bailey, R.L.; Blumberg, J.B.; Burton-Freeman, B.; Chen, C.-Y.O.; Crowe-White, K.M.; Drewnowski, A.; Hooshmand, S.; Johnson, E.; Lewis, R.; et al. Fruits, vegetables, and health: A comprehensive narrative, umbrella review of the science and recommendations for enhanced public policy to improve intake. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2174–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Only 1 in 10 Adults Get Enough Fruits or Vegetables. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/division-information/media-tools/adults-fruits-vegetables.html (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Jones, J.W.; Toossi, S.; Hodges, L. The Food and Nutrition Assistance Landscape: Fiscal Year 2021 Annual Report; EIB-237; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Puma, J.E.; Young, M.; Foerster, S.; Keller, K.; Bruno, P.; Franck, K.; Naja-Riese, A. The SNAP-Ed evaluation framework: Nationwide uptake and implications for nutrition education practice, policy, and research. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Shang, B.; Liang, W.; Du, G.; Yang, M.; Rhodes, R.E. Effects of eHealth-based multiple health behavior change interventions on physical activity, healthy diet, and weight in people with noncommunicable diseases: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, C.; Courtney, K.L.; Naylor, P.J.; E Rhodes, R. Tailored mobile text messaging interventions targeting type 2 diabetes self-management: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. Digit. Health 2019, 5, 2055207619845279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head, K.J.; Noar, S.M.; Iannarino, N.T.; Harrington, N.G. Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 97, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A.M.; Alley, S.; Schoeppe, S.; Vandelanotte, C. The effectiveness of e-& mHealth interventions to promote physical activity and healthy diets in developing countries: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; D’Agostino, M.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Alkmim, M.B.M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. The impact of mHealth interventions: Systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafson, A.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; McQuerry, K.; Babtunde, O.; Mullins, J. A Mentor-Led Text-Messaging Intervention Increases Intake of Fruits and Vegetables and Goal Setting for Healthier Dietary Consumption among Rural Adolescents in Kentucky and North Carolina, 2017. Nutrients 2019, 11, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, S.; Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Texting your way to healthier eating? Effects of participating in a feedback intervention using text messaging on adolescents’ fruit and vegetable intake. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, K.; Hyun, K.; de Keizer, L.; Thiagalingam, A.; Hillis, G.S.; Chalmers, J.; Redfern, J.; Chow, C.K. The effects of a lifestyle-focused text-messaging intervention on adherence to dietary guideline recommendations in patients with coronary heart disease: An analysis of the TEXT ME study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.M.S.; George, E.S.; Maddison, R. Effectiveness of a mobile phone text messaging intervention on dietary behaviour in patients with type 2 diabetes: A post-hoc analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Mhealth 2021, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, J.M.; Bersamin, A. A Text Messaging Intervention (Txt4HappyKids) to Promote Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Families With Young Children: Pilot Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2018, 2, e8544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, R.; Whittaker, R.; Jiang, Y.; Maddison, R.; Shepherd, M.; McNamara, C.; Cutfield, R.; Khanolkar, M.; Murphy, R. Effectiveness of text message based, diabetes self management support programme (SMS4BG): Two arm, parallel randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2018, 361, k1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosliner, W.F.C.; Strochlic, R.; Wright, S.; Yates-Berg, A.; Thompson, H.; Tang, H.; Melendrez, B. Feasibility and Response to the San Diego County, California, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Agency Sending Food and Nutrition Text Messages to All Participants: Quasi-Experimental Web-Based Survey Pilot Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, M.; Townsend, M.; Kaiser, L.; Martin, A.; West, E.; Turner, B.; Joy, A. Food behavior checklist effectively evaluates nutrition education. Calif. Agric. 2006, 60, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabli, J. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation is associated with an increase in household food security in a national evaluation. J. Nutr. 2015, 145, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoynes, H.; Schanzenbach, D.W.; Almond, D. Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016, 106, 903–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. SNAP Data Tables—National and/or State Level Monthly and/or Annual Data. Available online: https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/resource-files/34SNAPmonthly-12.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Voorheis, P.; Zhao, A.; Kuluski, K.; Pham, Q.; Scott, T.; Sztur, P.; Khanna, N.; Ibrahim, M.; Petch, J. Integrating Behavioral Science and Design Thinking to Develop Mobile Health Interventions: Systematic Scoping Review. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2022, 10, e35799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Focus Group Guide |

|---|

| 1. We’re interested in your thoughts on the text messages about fruits and vegetables that you got from CalFresh. How did you feel about getting these text messages? ∙ Probe: Did they feel different from the usual messages you get from CalFresh? What words or feelings come to mind? |

| 2. How did getting those messages make you feel about CalFresh? Was that any different from how you felt before? |

| 3. I’m going to share my screen and show you some of the text messages to refresh your memory [SHARE SCREEN AND DISPLAY MESSAGES]. What other thoughts come up for you on seeing these messages? What suggestions do you have for improving the text messages? Are there other ways you would prefer to get this information? ∙ Probe: content, FV highlighted, length, frequency, delivery (text vs. email), other |

| 4. We’re also interested in your thoughts about the website that the text messages linked to. What do you remember about the website? What did you like about it? What didn’t you like? |

| 5. What other thoughts or feelings come up for you on seeing the website? What do you think of the different sections? What suggestions do you have for improving the website? ∙ Probe: content, visuals, organization, navigation, interactivity/engagingness |

| 6. The text messages and website provided information about how to select, store, and prepare different fruits and vegetables, with recipes and tips for reducing food waste. Which aspects did you find most useful? What additional information would you like? |

| 7. Thinking about the text messages and website, what information was new or especially helpful for you? |

| 8. Can you tell us about any changes you’ve made in selecting, storing, or preparing fruits and vegetables, wasting food, or buying local or seasonal produce because of the text messages or website? |

| 9. CalFresh has been sending these messages for about a year. How would you feel about continuing to get these types of messages? ∙ Probe: How would you feel if you stopped getting them? |

| 10. All the messages so far have been about fruits and vegetables. What additional information would you like to get by text from CalFresh? |

| 11. Those are all the questions I have for you. Is there anything else you’d like to share about the text messages and website? |

| Focus Group # | Month | Time of Day | # of Participants, n = 26 | Language | Gender | Race/Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | November 2021 | Evening | 2 | Spanish | 2 Female | 2 Latino/Latina |

| 2 | November 2021 | Midday | 4 | Spanish | 4 Female | 3 Latino/Latina 1 White |

| 3 | December 2021 | Evening | 7 | Spanish | 6 Female 1 Male | 7 Latino/Latina |

| 4 | November 2021 | Evening | 2 | English | 2 Female | 1 White/Latina 1 White |

| 5 | November 2021 | Midday | 3 | English | 1 Female 2 Male | 1 Asian or Asian American 1 White 1 Latino/Latina |

| 6 | December 2021 | Evening | 5 | English | 3 Female 2 Male | 1 Asian or Asian American 1 Black or African American 1 White 1 Latino/Latina 1 Refused to answer |

| 7 | December 2021 | Evening | 3 | English | 3 Female | 1 Black or African American 2 White |

| Feelings about Receiving Text Messages about FV |

| Key Finding 1: Participants greatly appreciated receiving text messages with nutrition information |

| 1.1 I just really appreciated it, I think it’s really amazing. It’s like something that you sign up for, you know, when you sign up for those things that you see, like on Facebook or something… and they get you these, you know, foods that you should try and recipes that you should try and, you know, let you know what to eat and how much and you know, I just think it’s really important and I’m grateful for it. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 1.2 … it does remind me to think of it as a way to eat healthier. It’s kind of like when I get the messages, it’s like, oh, yeah, you know, I get a little bit extra. And that enables me to buy healthier foods. So, it is a good little reminder. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 1.3 Thank you very much for helping us…making us feel that…we can find options, know more, learn more. Because sometimes you forget that you need to keep up with information. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| Key Finding 2: Participants expressed they would like text messages to continue and many would prefer to receive them more frequently |

| 2.1 Oh, well, yes, of course I would like to keep getting them. Well, more often would be good, too, because that way… you learn more, instead of being forgotten for a month. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 2.2 So I would be really bummed [if the messages stopped] because for me the information is really valuable. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 2.3 I really liked the text messages. I think for a month I did not get them, and I was like, awww [making sad face] because I really liked the nutritional facts. |

| -Asian Female (English) |

| 2.4 For these, I wouldn’t have minded getting them like once a week, that would have been fine with me. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| Key Finding 3: Participants explained that the text messages about FV changed their feelings about SNAP, making them feel cared about and connected |

| 3.1 It’s more human… it implies that there’s some care about the person behind the…institution. When you’re in the welfare system in any way, even if the only part you’re getting is food stamps—I’ve gotten the full gamut throughout my life at different periods. It’s very dehumanizing. And you often feel a lot of negative emotions or feelings about it, embarrassment, shame, and just frustration that you’re just a number and things like that. I guess there’s a sense that when you get a text message, that’s cheerful and yeah, it’s information, there’s a little bit of a feeling that it’s more than that, that it’s caring about your health and your well-being. And I guess even though I know that it’s kind of coming from an institution also, it just has a different feeling about it for me. I think it’s, it shows that things are moving maybe in a more positive direction when it comes to public programs. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 3.2 I felt important. I felt that I was important to somebody, my, my eating habits, right? And, basically for my son’s eating habits. It feels good to have someone close by, helping you with tips. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 3.3 Oh my goodness. It just made me feel like, they care so much. You know, it was like, it made it personal for me… So, like, more intimate for me to have a relationship with, with CalFresh. |

| -Latina Female (English) |

| Feelings about the information |

| Key Finding 4: Participants expressed their appreciation for information regarding selecting, storing, and preparing FV |

| 4.1 Okay, it tells us in the link, it tells us how we can, um, select green beans. Choose fresh green beans that are thin. A lot of times we don’t know about the, um, vegetables, we don’t know which ones are the best that are in the best condition, or that are tender, that have the best texture for buying and, um, eating. So this tells us how they should look, including bright green color… Then how we should store them. I would like you to keep telling us about all this because sometimes we don’t know. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 4.2 I thought it was very interesting… for example, eat what’s in season because it’s cheaper, because they have more vitamins… it made me look for more information, so… it piqued my curiosity. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 4.3 … that’s one of my favorite parts because you, they give you tips, like I said before, on how to prepare a food or something you have at home. And well, obviously, well, you adjust it, whether to your budget or to your preferences, well, in this case, my kids are what I struggle with the most, to get them to eat fruits and vegetables. I adjust it to what they like, too, and I try to make changes. For me, that part is perfect. I loved it. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 4.4 Well, it’s knowing the quality of each fruit, what it contributes, to health, especially what time of year can you buy it, because that also helps you save. And yes, I have known that when there’s fruit in season, you need to buy it and use it and eat it because it really is cheaper than when it’s not in season, so I’m very interested in all this information, and I follow it and try to do it. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| Key Finding 5: Participants expressed their appreciation for the website, especially because of the recipes |

| 5.1 For me, it was the recipes for the most part, you know, looking at different, different ideas that maybe I hadn’t thought of… that part was very helpful. |

| -White Male (English) |

| 5.2 I’ve even taken recipes to places when I’m, you know, going to maybe like a small gathering of friends. I’ll take a recipe. I took a recipe of vegetable and rice that you guys had given out. And I took that with me and my friend said, ’Oh, honey, this is delicious.’ I was like I got it from food stamps. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 5.3 One of the essential tools that they tell us and that by nature is, besides what the doctor tells us, is eating food in a healthier way. Like for example, boiled green beans instead of fried, put them in the blender when they’re warm just boiled, eat them in soup. All those kinds of situations are going to help us to at least be a little healthier so we can counteract disease, and at the same time feel good, actually with ourselves and our family. All the products you’ve given us and the, and the recipes that you’ve also given us, I’ve made them here. The last time I made a recipe that I liked, that was a salad of all vegetables. |

| -Latino Male (Spanish) |

| Key Finding 6: Participants reported adopting new behaviors related to FV purchase, storage, preparation, and consumption as a result of receiving the messages and/or using the website |

| 6.1 Like, I look up, and now I go to a farmers’ market. And I try to buy local now, I never, never even thought about that. I hate to say that, but it was something I never thought about until you guys sent me that. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 6.2 Can I tell you, I had never had persimmons. So after I read all the nutritional value of persimmons, I went and got, like three. I’ve never had one…They’re delicious… I had persimmons and kiwi and…I am eating bell peppers now. I never really ate bell peppers. |

| -White Female (English) |

| 6.3 I received the message about persimmons. I already knew about them. I had never tasted them, but thanks to the link…we went and bought some and loved them. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 6.4 I do remember getting the kiwi one as well. And I’m not a real big kiwi fan, but I did go out and buy some and, and try them out. And I mix those in smoothies as well, which I thought was quite interesting. |

| -Latino Male (English) |

| 6.5 Well, I felt very privileged to get those because every time there was a text message, and there was a fruit suggested that we try with the…details and all that. If I wasn’t trying it already, I went out and I bought it and tried it. And now it’s a part of my regular diet. |

| -White Female (English) |

| Key Finding 7: Participants would like to receive many other types of information |

| 7.1 I like how you’re talking about the composting and about that, like, if we get a text message about that, maybe it’ll encourage more people to do it, like, see it not waste as much food. Those are good ideas too. |

| -Asian Female (English) |

| 7.2 I still would like to know something about drinks. You know, I’m trying to move away from soda completely to incorporate more water, but it just we be missing alternatives to just water, healthy drinks. Not sugary, sugar laced, you know, calorie concentrated. Like what, I don’t, yeah, you don’t know what else to drink besides water. |

| -Didn’t wish to answer Female (English) |

| 7.3 Yeah. Anti-inflammatory, anti-sugar. You know, I mean, I mean, I know that’s really asking a lot that you know, just once in a while like to get a sugar-free, flour-free sweet. |

| -White Female (English) |

| Barriers |

| Sub-Finding 1: Participants expressed concerns about clicking on the link, but noted that the SNAP agency is a trusted source |

| 8.1 At first, my response was to not pay too much attention, but um, since I saw it came from, from CalFresh, right? From the county, then I felt sure, sure it was real because, well, we’ve been warned not to fall for the trap of people who aren’t who they say they are. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 8.2 Nowadays it’s mainly, because of the situation, whether it’s phone calls, if it’s fraud scams. So, I would think along those lines about not trusting. Or you click on it and…maybe it already sent you to another link, or they want to steal your information. I would think along those lines about not trusting, thinking it might be spam or something like that, or someone wants to go in and steal your information from the beginning. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| Sub-Finding 2: Participants explained that limited internet access was a barrier to visiting the website |

| 9.1 Supposedly I have unlimited Internet, supposedly. I pay, but it’s not true. You use like five gigs and there’s no more. So the, the five few gigabytes I have for the whole month, I try to save them however I can, right? Not watching or looking at too many things that use up my Internet if I’m away from home. |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

| 9.2 The truth is, I like texts better because I’m more, like, I don’t have much Internet on the phone, and text messages, I can get them. So I imagine that, like me, there’s a lot of people, right? |

| -Latina Female (Spanish) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Felix, C.; Strochlic, R.; Melendrez, B.; Tang, H.; Wright, S.; Gosliner, W. Perceptions and Experiences of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants Related to Receiving Food and Nutrition-Related Text Messages Sent Agency-Wide: Findings from Focus Groups in San Diego County, California. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122684

Felix C, Strochlic R, Melendrez B, Tang H, Wright S, Gosliner W. Perceptions and Experiences of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants Related to Receiving Food and Nutrition-Related Text Messages Sent Agency-Wide: Findings from Focus Groups in San Diego County, California. Nutrients. 2023; 15(12):2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122684

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelix, Celeste, Ron Strochlic, Blanca Melendrez, Hao Tang, Shana Wright, and Wendi Gosliner. 2023. "Perceptions and Experiences of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants Related to Receiving Food and Nutrition-Related Text Messages Sent Agency-Wide: Findings from Focus Groups in San Diego County, California" Nutrients 15, no. 12: 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122684

APA StyleFelix, C., Strochlic, R., Melendrez, B., Tang, H., Wright, S., & Gosliner, W. (2023). Perceptions and Experiences of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participants Related to Receiving Food and Nutrition-Related Text Messages Sent Agency-Wide: Findings from Focus Groups in San Diego County, California. Nutrients, 15(12), 2684. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15122684