Which Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Is Better? The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Type on Consumers’ Healthy Food Purchase Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Hypotheses Development

2.2.1. Nutrition Label Type

2.2.2. Moderating Role of Spokesperson Type

3. Methodology

3.1. Study 1: Differences between Evaluative and Objective Nutrition Labels

3.1.1. Method

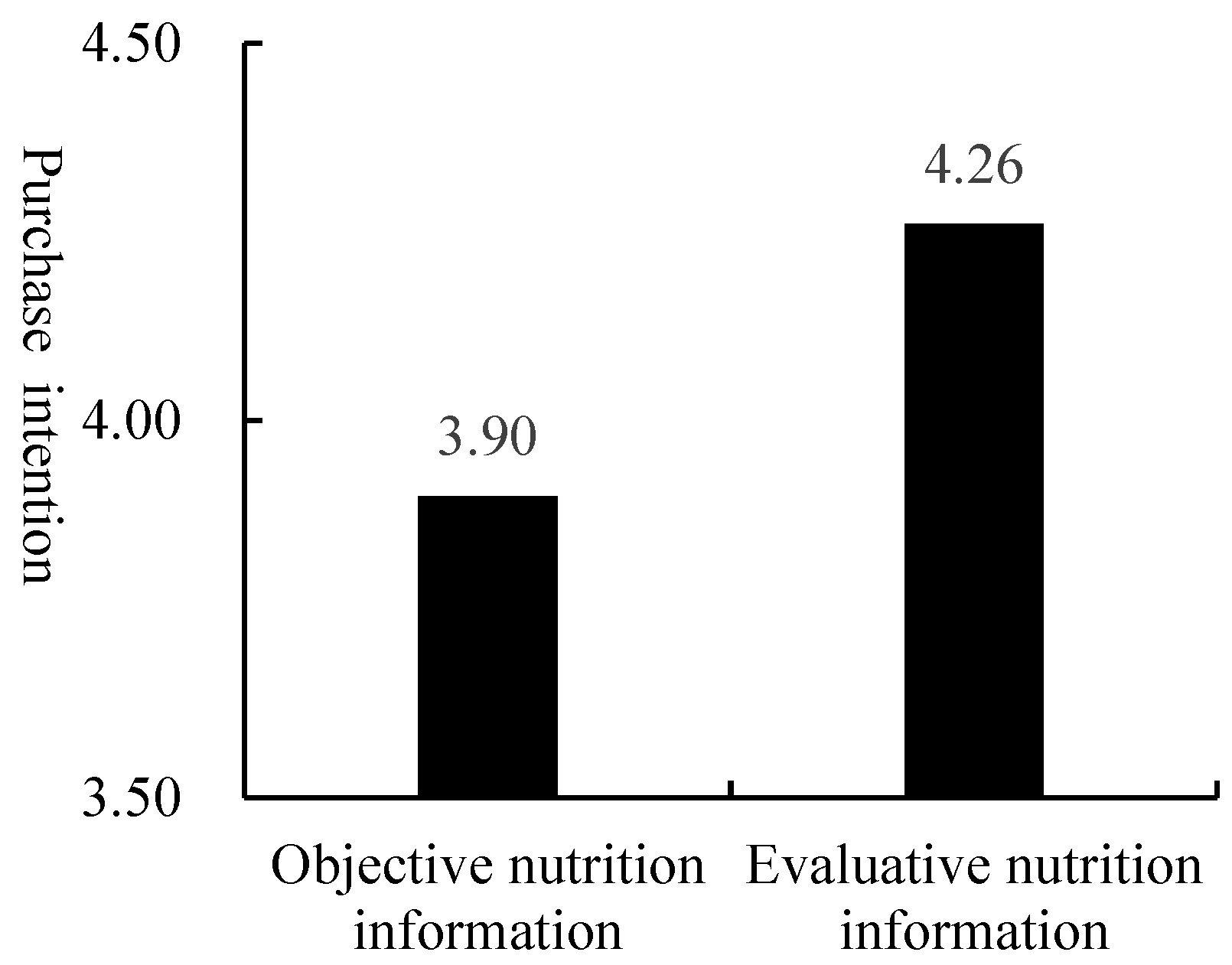

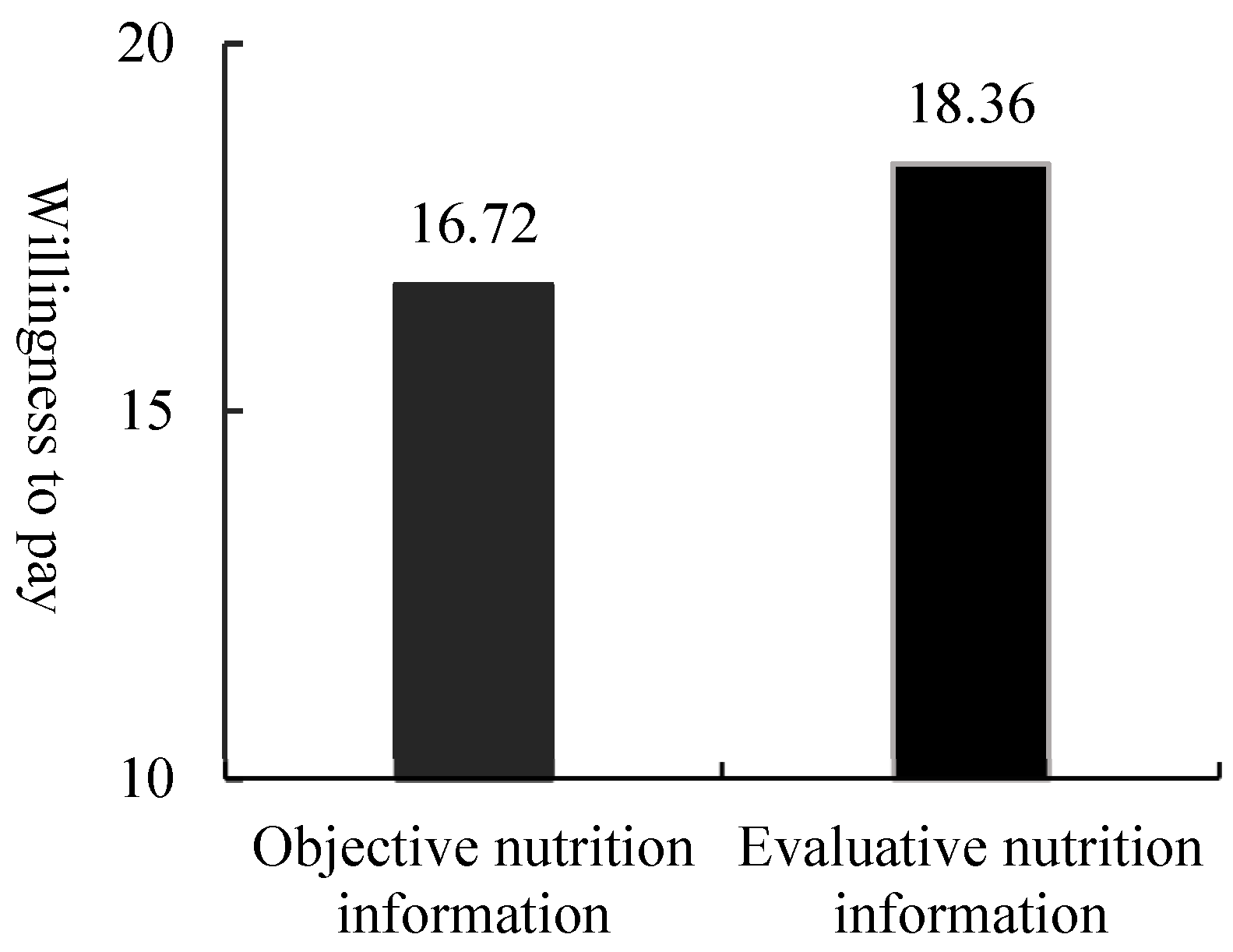

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Study 2: The Influence of FOP Nutrition Label Type on Consumer Purchase Behavior

3.2.1. Method

3.2.2. Results

3.2.3. Discussion

3.3. Study 3: Moderating Effect of Spokesperson Type

3.3.1. Method

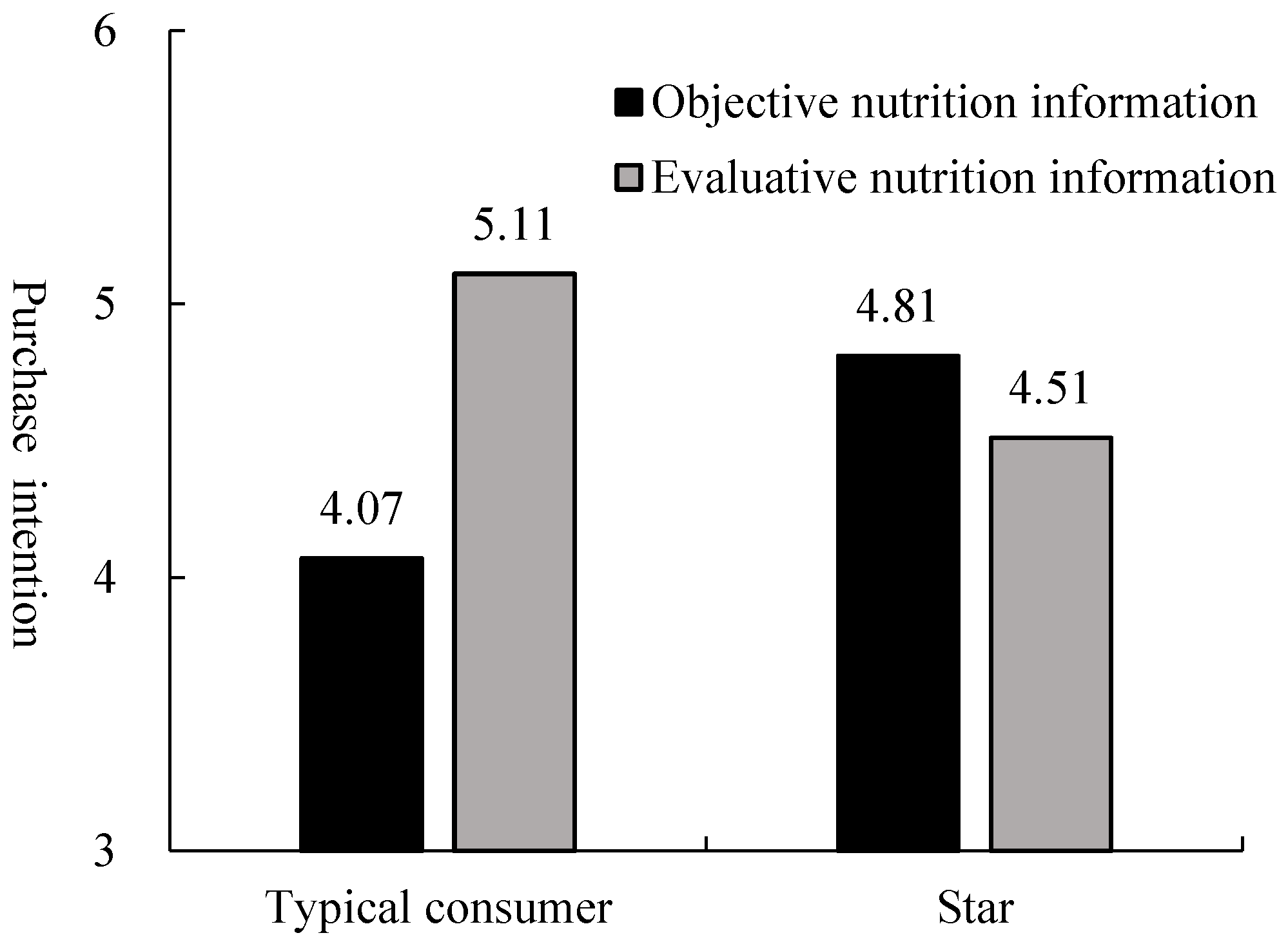

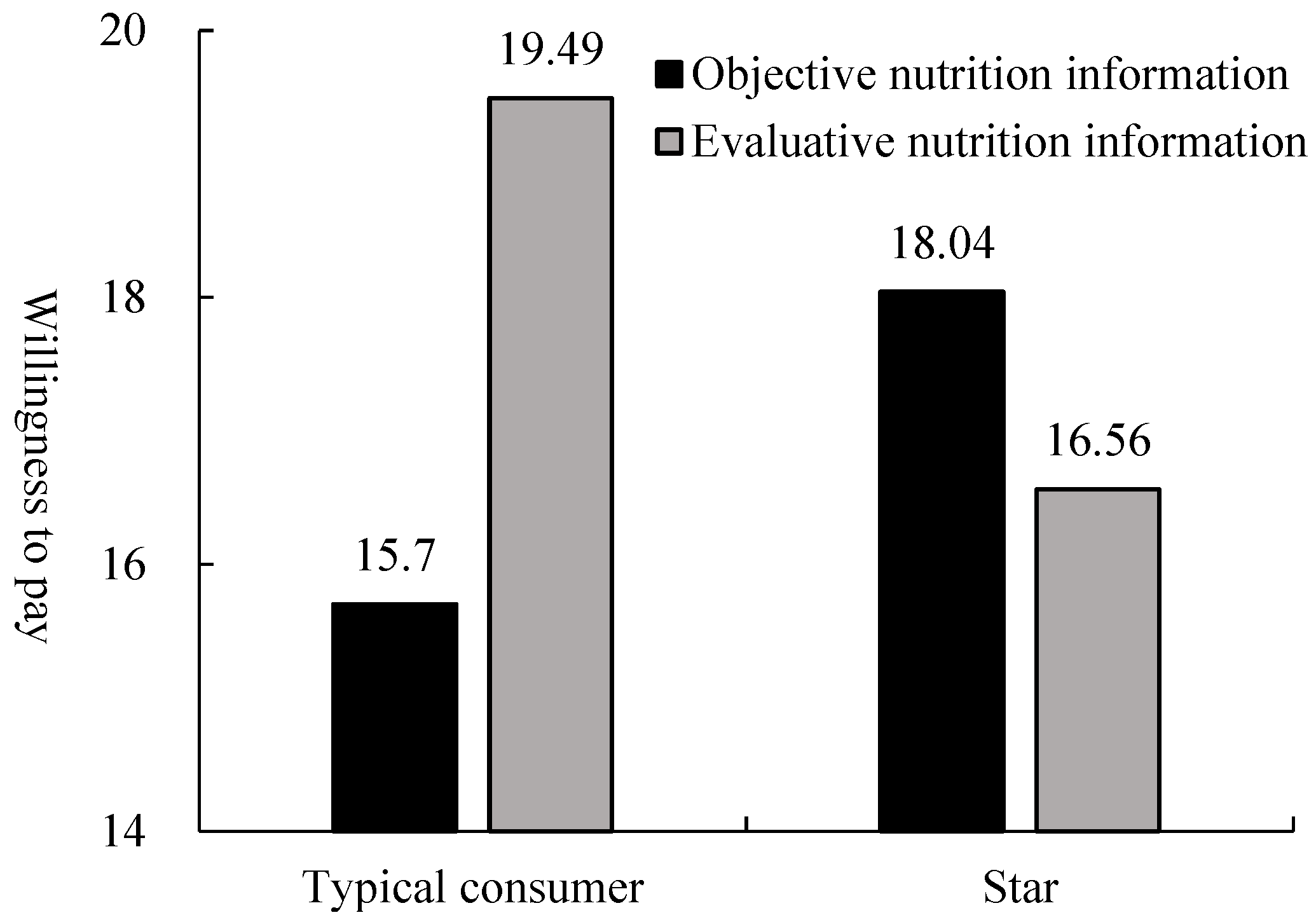

3.3.2. Results

3.3.3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Obesity and Overweight. Key Facts. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Ungar, R. Obesity Now Costs Americans More in Healthcare Spending than Smoking. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rickungar/2012/04/30/obesity-now-costs-americans-more-in-healthcare-costs-than-smoking/#5cfc435653d7 (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Popkin, B.M.; Kim, S.; Rusev, E.R.; Du, S.; Zizza, C. Measuring the Full Economic Costs of Diet, Physical Activity and Obesity-Related Chronic Diseases. Obes. Rev. 2006, 7, 271–293. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.C.; Burton, S.; Cook, L.A. Nutrition Labeling in the United States and the Role of Consumer Processing, Message Structure, and Moderating Conditions; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolova, H.D.; Inman, J.J. Healthy Choice: The Effect of Simplified Point-of-Sale Nutritional Information on Consumer Food Choice Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 817–835. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, M.; Tillack, K.; Jordan Lin, C. Communicating Nutrition Information at the Point of Purchase: An Eye-tracking Study of Shoppers at Two Grocery Stores in the United States. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2018, 42, 557–565. [Google Scholar]

- Ni Mhurchu, C.; Volkova, E.; Jiang, Y.; Eyles, H.; Michie, J.; Neal, B.; Blakely, T.; Swinburn, B.; Rayner, M. Effects of Interpretive Nutrition Labels on Consumer Food Purchases: The Starlight Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 105, 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, C.L.; Howlett, E.; Burton, S. Effects of Objective and Evaluative Front-of-Package Cues on Food Evaluation and Choice: The Moderating Influence of Comparative and Noncomparative Processing Contexts. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 42, 749–766. [Google Scholar]

- Feunekes, G.I.J.; Gortemaker, I.A.; Willems, A.A.; Lion, R.; van den Kommer, M. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labelling: Testing Effectiveness of Different Nutrition Labelling Formats Front-of-Pack in Four European Countries. Appetite 2008, 50, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; Juhl, H.J.; Wasowicz-Kirylo, G.; Stysko-Kunkowska, M.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Attention Mediates the Effect of Nutrition Label Information on Consumers’ Choice. Evidence from a Choice Experiment Involving Eye-Tracking. Appetite 2014, 76, 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, H.M.; de Vlieger, N.; Collins, C.; Bucher, T. The Influence of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Information on Consumers’ Portion Size Perceptions. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2017, 28, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Arrúa, A.; Curutchet, M.R.; Rey, N.; Barreto, P.; Golovchenko, N.; Sellanes, A.; Velazco, G.; Winokur, M.; Giménez, A.; Ares, G. Impact of Front-of-Pack Nutrition Information and Label Design on Children’s Choice of Two Snack Foods: Comparison of Warnings and the Traffic-Light System. Appetite 2017, 116, 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Khandpur, N.; Sato, P.D.M.; Mais, L.A.; Martins, A.P.B.; Spinillo, C.G.; Garcia, M.T.; Rojas, C.F.U.; Jaime, P.C. Are Front-of-Package Warning Labels More Effective at Communicating Nutrition Information than Traffic-Light Labels? A Randomized Controlled Experiment in a Brazilian Sample. Nutrients 2018, 10, 688. [Google Scholar]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; van Trijp, H. Standing Out in the Crowd: The Effect of Information Clutter on Consumer Attention for Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels. Food Policy 2013, 41, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J.H.; Rishika, R.; Janakiraman, R.; Kannan, P.K. Competitive Effects of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling Adoption on Nutritional Quality: Evidence from Facts Up Front–Style Labels. J. Mark. 2020, 84, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, B.; Crino, M.; Dunford, E.; Gao, A.; Greenland, R.; Li, N.; Ngai, J.; Ni Mhurchu, C.; Pettigrew, S.; Sacks, G.; et al. Effects of Different Types of Front-of-Pack Labelling Information on the Healthiness of Food Purchases—A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1284. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shium, E.M.K.; Michaelidou, N. The Influence of Nutrition Information on Choice: The Roles of Temptation, Conflict and Self-Control. J. Consum. Aff. 2010, 44, 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Mauri, C.; Grazzini, L.; Ulqinaku, A.; Poletti, E. The Effect of Front-of-Package Nutrition Labels on The Choice of Low Sugar Products. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, H.; Scully, M.; Morley, B.; Wakefield, M. Can Point-of-Sale Nutrition Information Encourage Reduced Preference for Sugary Drinks Among Adolescents? Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4023–4034. [Google Scholar]

- Ducrot, P.; Julia, C.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Touvier, M.; Fezeu, L.K.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. Impact of Different Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels on Consumer Purchasing Intentions: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J. The Effects of Nutrient Ad Disclosures of Fast Food Menu Items on Consumer Selection Behaviors Regarding Subjective Nutrition Knowledge and Body Mass Index. Br. Food J. 2013, 115, 1281–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, G.-X.; Kronrod, A. Is the Devil in the Details? J. Advert. 2012, 41, 103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Tan, C.-H.; Ke, W.; Wei, K.-K. Do we order product review information display? How? Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 883–894. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, J.; Hammond, D. Efficacy and Consumer Preferences for Different Approaches to Calorie Labeling on Menus. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 669–675. [Google Scholar]

- Berning, J.P.; Chouinard, H.H.; McCluskey, J.J. Consumer Preferences for Detailed Versus Summary Formats of Nutrition Information on Grocery Store Shelf Labels. J. Agric. Food. Ind. Organ. 2008, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.C.; Burton, S.; Kees, J. Is Simpler Always Better? Consumer Evaluations of Front-of-Package Nutrition Symbols. J. Public Policy Mark. 2011, 30, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhaker, P.R.; Sauer, P. Hierarchical Heuristics in Evaluation of Competitive Brands Based on Multiple Cues. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- van Herpen, E.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labels. Their Effect on Attention and Choices When Consumers Have Varying Goals and Time Constraints. Appetite 2011, 57, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Friestad, M.; Wright, P. The Persuasion Knowledge Model: How People Cope with Persuasion Attempts. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, A.; Patrick, V.M. Anytime Versus Only: Mind-Sets Moderate the Effect of Expansive Versus Restrictive Frames on Promotion Evaluation. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 462–472. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.M.Y. Codeswitching in Campaigning Discourse: The Case of Taiwanese President Chen Shuibian. Lang. Linguist. 2003, 4, 139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. 2. The measurement of self-esteem. In Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965; pp. 16–36. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaubert, L.; Krukowski, S.; Bodemer, D. Assumptions and Confidence of Others: The Impact of Socio-Cognitive Information on Metacognitive Self-Regulation. Metacogn. Learn. 2021, 16, 855–887. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Brion, S.; Moore, D.A.; Kennedy, J.A. A Status-Enhancement Account of Overconfidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 103, 718–735. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Kilduff, G.J. Why Do Dominant Personalities Attain Influence in Face-to-Face Groups? The Competence-Signaling Effects of Trait Dominance. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, C.L.; Howlett, E.; Burton, S. Shopper Response to Front-of-Package Nutrition Labeling Programs: Potential Consumer and Retail Store Benefits. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, C.; Burton, S.; Howlett, E. The Effects of Voluntary Versus Mandatory Menu Calorie Labeling on Consumers’ Retailer-Related Responses. J. Retail. 2018, 94, 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.L.; Garbinsky, E.N.; Vohs, K.D. Cultivating Admiration in Brands: Warmth, Competence, and Landing in the “Golden Quadrant”. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kervyn, N.; Fiske, S.T.; Malone, C. Brands as Intentional Agents Framework: How Perceived Intentions and Ability Can Map Brand Perception. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, J.; Vohs, K.D.; Mogilner, C. Nonprofits Are Seen as Warm and For-Profits as Competent: Firm Stereotypes Matter. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra, O.; Chan, E.; Hyekyung, P.; Burnstéin, E.; Monin, B.; Stańik, C. Life’s Recurring Challenges and the Fundamental Dimensions: An Integration and Its Implications for Cultural Differences and Similarities. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 38, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Abele, A.E.; Bruckmüller, S. The Bigger One of the ‘Big Two’? Preferential Processing of Communal Information. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 47, 935–948. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, H.H.; Friedman, L. Endorser Effectiveness by Product Type. J. Advert. Res. 1979, 19, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.J.; Sherrell, D.L. Source Effects in Communication and Persuasion Research: A Meta-Analysis of Effect Size. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.; Kim, J.; Sung, Y. AI-Powered Recommendations: The Roles of Perceived Similarity and Psychological Distance on Persuasion. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 1366–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeh, J.K. Travellers’ Acceptance of Consumer-Generated Media: An Integrated Model of Technology Acceptance and Source Credibility Theories. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity Vs. Influencer Endorsements in Advertising: The Role of Identification, Credibility, and Product-Endorser Fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Huang, Y.-H.; Wu, F.; Choy, H.-Y.; Lin, D. At the Crossroads of Inclusion and Distance: Organizational Crisis Communication during Celebrity-Endorsement Crises in China. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Dempsey, M.A. Processing Difficulty Increases Perceived Competence of Brand Acronyms. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2019, 36, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Freddi, S.; Tessier, M.; Lacrampe, R.; Dru, V. Affective Judgement about Information Relating to Competence and Warmth: An Embodied Perspective. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 53, 265–280. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Teng, L.; Liao, Y. Counterfeit Luxuries: Does Moral Reasoning Strategy Influence Consumers’ Pursuit of Counterfeits? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Krishnan, B.; Pullig, C.; Wang, G.; Yagci, M.; Dean, D.; Ricks, J.; Wirth, F. Developing and Validating Measures of Facets of Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liao, F.; Li, H. Which Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Is Better? The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Type on Consumers’ Healthy Food Purchase Behavior. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102326

Liao F, Li H. Which Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Is Better? The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Type on Consumers’ Healthy Food Purchase Behavior. Nutrients. 2023; 15(10):2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102326

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiao, Fen, and Han Li. 2023. "Which Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Is Better? The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Type on Consumers’ Healthy Food Purchase Behavior" Nutrients 15, no. 10: 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102326

APA StyleLiao, F., & Li, H. (2023). Which Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Is Better? The Influence of Front-of-Package Nutrition Label Type on Consumers’ Healthy Food Purchase Behavior. Nutrients, 15(10), 2326. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102326