Equally Good Neurological, Growth, and Health Outcomes up to 6 Years of Age in Moderately Preterm Infants Who Received Exclusive vs. Fortified Breast Milk—A Longitudinal Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

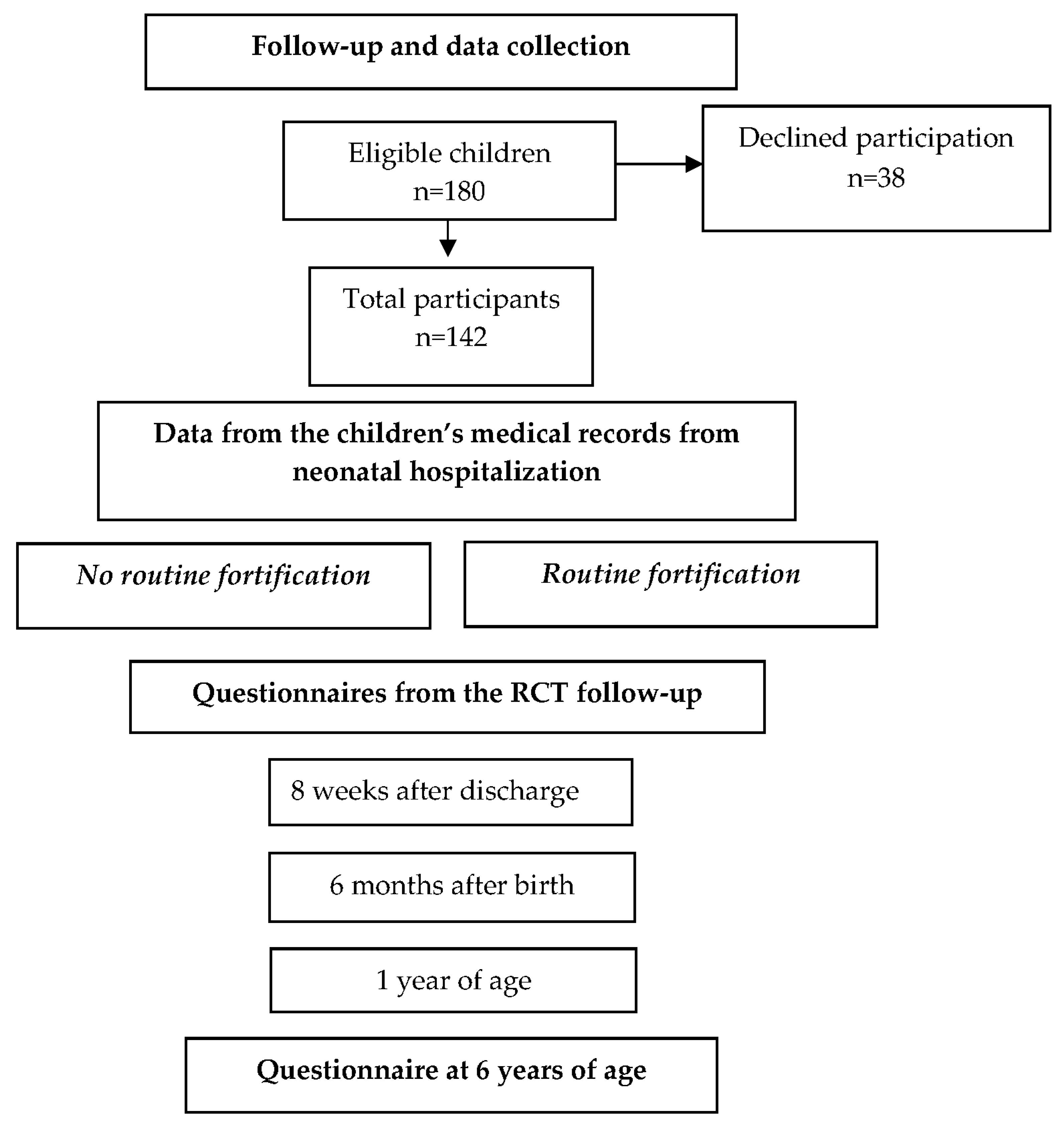

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes

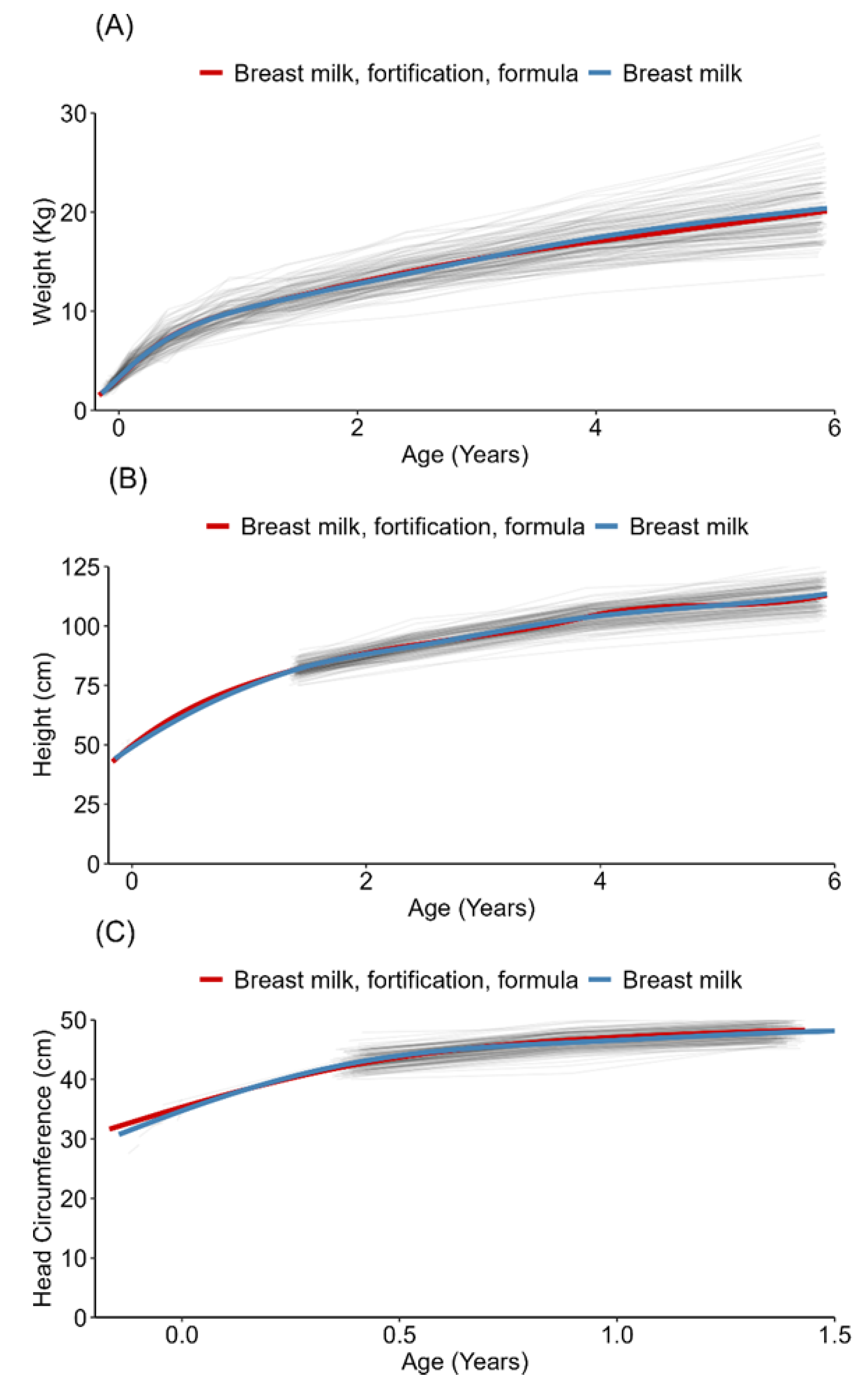

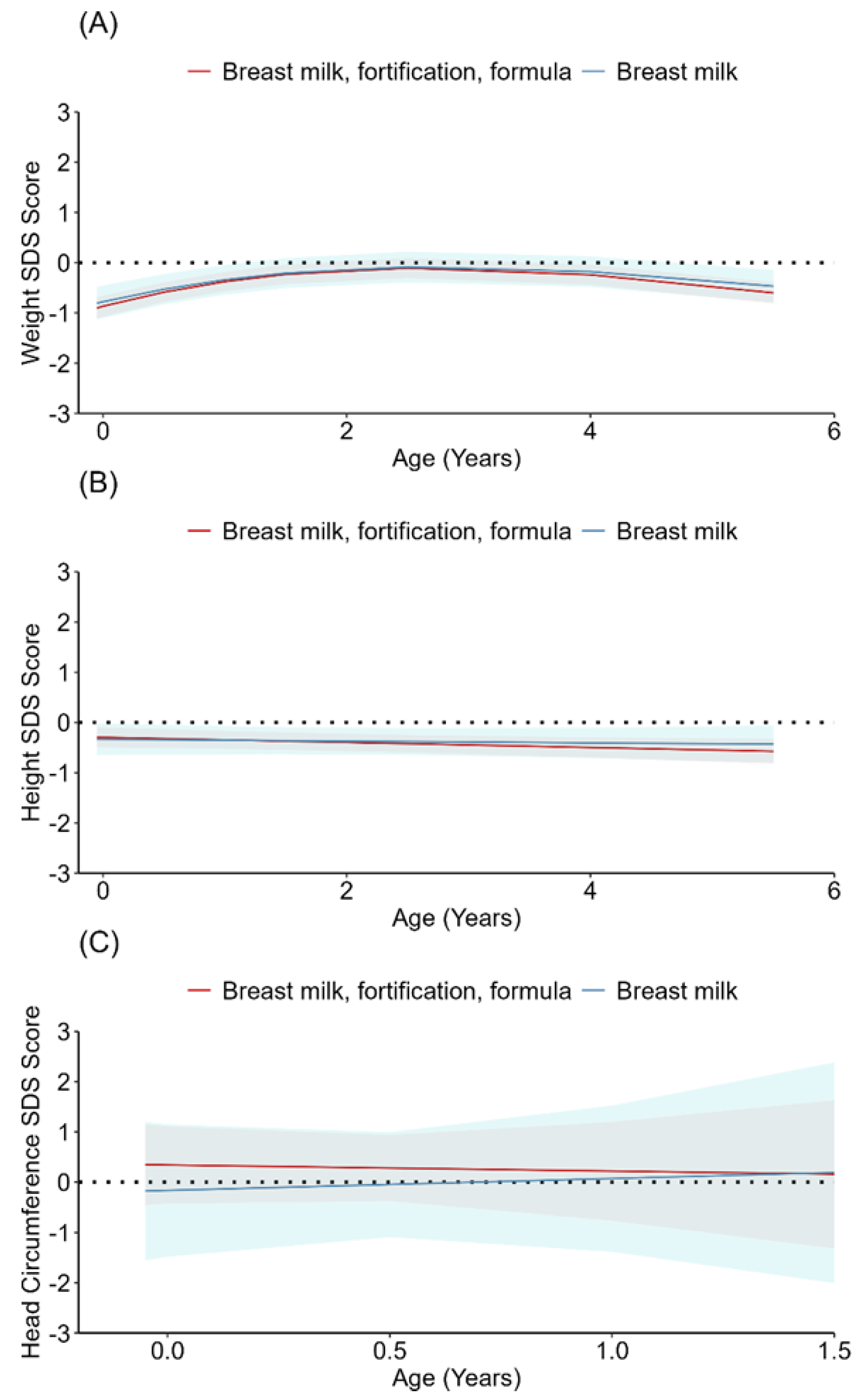

3.2. Growth

3.3. Health

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Gamarra-Oca, L.F.; Ojeda, N.; Gómez-Gastiasoro, A.; Peña, J.; Ibarretxe-Bilbao, N.; García-Guerrero, M.A.; Loureiro, B.; Zubiaurre-Elorza, L. Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcomes after Moderate and Late Preterm Birth: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. 2021, 237, 168–176.e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for Care of the Preterm or Low-Birth-Weight Infant. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240058262 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Lechner, B.E.; Vohr, B.R. Neurodevelopmental Outcomes of Preterm Infants Fed Human Milk: A Systematic Review. Clin. Perinatol. 2017, 44, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victora, C.G.; Bahl, R.; Barros, A.J.D.; França, G.V.A.; Horton, S.; Krasevec, J.; Murch, S.; Sankar, M.J.; Walker, N.; Rollins, N.C. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet 2016, 387, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horta, B.L.; de Sousa, B.A.; de Mola, C.L. Breastfeeding and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horta, B.L.; Loret de Mola, C.; Victora, C.G. Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, R.; Eidelman, A.I. Direct and indirect effects of breast milk on the neurobehavioral and cognitive development of premature infants. Devl. Psychobiol. 2003, 43, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, M.; Elliott, M.J.; Abraham, J.H. Decreased cost and improved feeding tolerance in VLBW infants fed an exclusive human milk diet. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, M.S.; Kakuma, R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; p. Cd003517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapillonne, A.; Bronsky, J.; Campoy, C.; Embleton, N.; Fewtrell, M.; Fidler Mis, N.; Gerasimidis, K.; Hojsak, I.; Hulst, J.; Indrio, F.; et al. Feeding the Late and Moderately Preterm Infant: A Position Paper of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 69, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochow, N.; Raja, P.; Liu, K.; Fenton, T.; Landau-Crangle, E.; Göttler, S.; Jahn, A.; Lee, S.; Seigel, S.; Campbell, D.; et al. Physiological adjustment to postnatal growth trajectories in healthy preterm infants. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N.E.; Pang, N.; Cooke, R.J. Postnatal malnutrition and growth retardation: An inevitable consequence of current recommendations in preterm infants? Pediatrics 2001, 107, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.J.; Ainsworth, S.B.; Fenton, A.C. Postnatal growth retardation: A universal problem in preterm infants. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 2004, 89, F428–F430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leppanen, M.; Lapinleimu, H.; Lind, A.; Matomaki, J.; Lehtonen, L.; Haataja, L.; Rautava, P. Antenatal and postnatal growth and 5-year cognitive outcome in very preterm infants. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, I.; Sticker, E.J.; Lentze, M.J. Catch-up growth of head circumference of very low birth weight, small for gestational age preterm infants and mental development to adulthood. J. Pediatr. 2003, 142, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas, R.; Sanz, M.P.; Fernandez-Calle, P.; Alcaide, M.J.; Montes, M.T.; Pastrana, N.; Segovia, C.; Omenaca, F.; Saenz de Pipaon, M. Experimental study showed that adding fortifier and extra-hydrolysed proteins to preterm infant mothers’ milk increased osmolality. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 105, e555–e560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panczuk, J.K.; Unger, S.; Francis, J.; Bando, N.; Kiss, A.; O’Connor, D.L. Introduction of Bovine-Based Nutrient Fortifier and Gastrointestinal Inflammation in Very Low Birth Weight Infants as Measured by Fecal Calprotectin. Breastfeed. Med. 2016, 11, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl-Jones, W.; Archibald, A.; Gordon, J.W.; Mughal, W.; Hossain, Z.; Friel, J.K. Human Milk Fortification Increases Bnip3 Expression Associated With Intestinal Cell Death In Vitro. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 61, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, A.M.; Finken, M.J.; Keijzer-Veen, M.G.; Hille, E.T.; Wit, J.M.; Dekker, F.W. Associations between prenatal and infancy weight gain and BMI, fat mass, and fat distribution in young adulthood: A prospective cohort study in males and females born very preterm. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, A.M.; de Wit, C.C.; Finken, M.J.; Rijken, M.; Wit, J.M. Growth of preterm born children. Horm. Res. 2008, 70, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N.D. Early nutrition and later outcomes in preterm infants. World Rev. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 106, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Evans, T.A.; Draper, E.S.; Field, D.J.; Manktelow, B.N.; Marlow, N.; Matthews, R.; Petrou, S.; Seaton, S.E.; Smith, L.K.; et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes following late and moderate prematurity: A population-based cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal. Ed. 2015, 100, F301–F308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.; Hamilton, M.; Johnson, T.J.; Greene, M.; Dabrowski, E.; Meier, P.P.; Patel, A.L. NICU Human Milk Dose and 20-Month Neurodevelopmental Outcome in Very Low Birth Weight Infants. Neonatology 2017, 112, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansson, J.; Fellman, V.; Stjernqvist, K. The ESG: Extremely preterm birth affects boys more and socio-economic and neonatal variables pose sex-specific risks. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roze, J.C.; Darmaun, D.; Boquien, C.Y.; Flamant, C.; Picaud, J.C.; Savagner, C.; Claris, O.; Lapillonne, A.; Mitanchez, D.; Branger, B.; et al. The apparent breastfeeding paradox in very preterm infants: Relationship between breast feeding, early weight gain and neurodevelopment based on results from two cohorts, EPIPAGE and LIFT. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e000834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutrium. Available online: www.nutrium.se (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Ericson, J.; Eriksson, M.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Hoddinott, P.; Flacking, R. Proactive telephone support provided to breastfeeding mothers of preterm infants after discharge: A randomised controlled trial. Acta Pediatr. 2018, 107, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadesjö, B.; Janols, L.O.; Korkman, M.; Mickelsson, K.; Strand, G.; Trillingsgaard, A.; Gillberg, C. The FTF (Five to Fifteen): The development of a parent questionnaire for the assessment of ADHD and comorbid conditions. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 13 (Suppl. S3), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklasson, A.; Albertsson-Wikland, K. Continuous growth reference from 24th week of gestation to 24 months by gender. BMC Pediatr. 2008, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericson, J.; Eriksson, M.; Hoddinott, P.; Hellstrom-Westas, L.; Flacking, R. Breastfeeding and risk for ceasing in mothers of preterm infants-Long-term follow-up. Matern. Child. Nutr. 2018, 14, e12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.V.; Lin, L.; Embleton, N.D.; Harding, J.E.; McGuire, W. Multi-nutrient fortification of human milk for preterm infants. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Volume 6, p. Cd000343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochow, N.; Raja, P.; Straube, S.; Voigt, M. Misclassification of newborns due to systematic error in plotting birth weight percentile values. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e347–e351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koletzko, B.; von Kries, R.; Closa, R.; Escribano, J.; Scaglioni, S.; Giovannini, M.; Beyer, J.; Demmelmair, H.; Gruszfeld, D.; Dobrzanska, A.; et al. Lower protein in infant formula is associated with lower weight up to age 2 y: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1836–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | Routine Fortification | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Neonatal unit 1 | 35 (25) | 10 (29) | 25 (71) | Yes |

| Neonatal unit 2 | 20 (14) | 0 | 20 (100) | Yes |

| Neonatal unit 3 | 26 (18) | 11 (42) | 15 (58) | No |

| Neonatal unit 4 | 31 (22) | 14 (45) | 17 (55) | No |

| Neonatal unit 5 | 19 (13) | 4 (21) | 15 (79) | Yes |

| Neonatal unit 6 | 11 (8) | 4 (36) | 7 (64) | No |

| Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at infant birth (years) | 31.1 ± 4.6 | 29.8 ± 4.5 | 31.7 ± 4.5 | 0.02 |

| Higher education | 103 (73) | 27 (63) | 76 (77) | 0.07 |

| Primipara | 72 (51) | 26 (63) | 46 (47) | 0.05 |

| Mother born in another country | 10 (7) | 2 (5) | 8 (8) | 0.37 |

| Cesarean section | 60 (42) | 16 (37) | 44 (44) | 0.27 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 34 [2] | 34 [1] | 34 [2] | 0.84 |

| Multiple births | 11 (8) | 0 | 11 (12) | 0.01 |

| Male | 74 (52) | 19 (44) | 55 (56) | 0.14 |

| Small for gestational age | 8 (6) | 2 (5) | 6 (6) | 0.54 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 2445 ± 466 | 2474 ± 428 | 2438 ± 483 | 0.68 |

| Birth length (centimeters) | 45.9 ± 2.8 | 46 ± 2.6 | 45.9 ± 2.6 | 0.87 |

| Birth head circumference (centimeters) | 32.3 ± 1.6 | 32.3 ± 1.4 | 32.2 ± 1.7 | 0.68 |

| Neonatal illness (NEC, ROP, PVL, BPD, congenital malformation) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Antibiotics | 19 (13) | 7 (16) | 12 (12) | 0.34 |

| Hypoglycemia | 49 (36) | 15 (37) | 34 (36) | 0.56 |

| Glucose infusion | 42 (30) | 14 (33) | 28 (29) | 0.37 |

| Partial parental nutrition | 9 (6) | 4 (9) | 5 (5) | 0.28 |

| Donated breast milk | 117 (82) | 42 (98) | 75 (76) | <0.001 |

| Fortification | 33 (23) | 0 | 33 (33) | |

| Number of days with fortification | ||||

| Formula | 74 (52) | 0 | 74 (75) | |

| Exclusive breast milk | 43 (30) | 43 (100) | 0 | |

| First day of free feeding | 17 [12.25] | 15 [8] | 18 [13] | 0.03 |

| Hospital stay (days) | 22 [13] | 20 [11] | 22 [13] | 0.09 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding at discharge | 127 (89) | 42 (98) | 85 (86) | 0.03 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 8 weeks after discharge | 102 (72) | 35 (81) | 67 (68) | 0.07 |

| Exclusive breastfeeding 6 months after birth | 41 (29) | 13 (30) | 28 (28) | 0.57 |

| Breastfeeding at one year of age | 18 (13) | 3 (7) | 15 (15) | 0.14 |

| Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | Logistic Regression Model * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Problem | Problems | No Problem | Problems | No Problem | Problems | OR 95% CI | p Value | |

| Motor skills | 126 (89) | 15 (11) | 39 (91) | 4 (9) | 88 (89) | 11 (11) | 1.20 (0.35–4.15) | 0.77 |

| Executive functioning | 135 (95) | 7 (5) | 40 (93) | 3 (7) | 95 (96) | 4 (4) | 0.64 (0.13–3.23) | 0.59 |

| Perception | 124 (87) | 18 (13) | 39 (93) | 4 (9) | 85 (86) | 14 (14) | 1.89 (0.57–6.34) | 0.30 |

| Memory | 133 (94) | 9 (6) | 41 (95) | 2 (5) | 92 (93) | 7 (7) | 1.48 (0.29–7.64) | 0.64 |

| Language | 122 (86) | 20 (14) | 38 (88) | 5 (12) | 84 (4) | 15 (15) | 1.66 (0.52–5.31) | 0.39 |

| Social skills | 134 (94) | 8 (6) | 42 (98) | 1 (2) | 92 (93) | 7 (7) | 2.81 (0.32–24.6) | 0.35 |

| Emotional/behavioral problems | 129 (91) | 13 (9) | 41 (95) | 2 (5) | 88 (88) | 11 (11) | 2.46 (0.48–12.5) | 0.46 |

| Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Domain | |||

| Motor skills | ref | 1.25 (0.78–1.98) | 0.35 |

| Executive functioning | 1.08 (0.71–1.65) | 0.71 | |

| Perception | 1.17 (0.76–1.80) | 0.49 | |

| Memory | 1.41 (0.85–2.35) | 0.18 | |

| Language | 1.49 (0.93–2.39) | 0.10 | |

| Social skills | 1.10 (0.69–1.78) | 0.69 | |

| Emotional/behavioral problems | 0.92 (0.59–1.44) | 0.72 | |

| Subdomain | |||

| Gross motor skills | 1.32 (0.78–2.30) | 0.33 | |

| Fine motor skills | 1.19 (0.73–1.95) | 0.48 | |

| Attention | 1.11 (0.70–1.76) | 0.65 | |

| Hyperactivity | 0.98 (0.63–1.54) | 0.93 | |

| Hypoactivity | 0.79 (0.42–1.49) | 0.46 | |

| Planning | 1.64(0.86–3.02) | 0.13 | |

| Perception of space | 1.12 (0.58–2.13) | 0.74 | |

| Perception of time | ref | 1.08 (0.69–1.70) | 0.74 |

| Perception of body | 1.62 (0.85–3.09) | 0.14 | |

| Visual body perception | 0.89 (0.39–2.05) | 0.78 | |

| Comprehension | 1.33 (0.73–2.43) | 0.35 | |

| Expressive speech | 1.46 (0.86–2.48) | 0.17 | |

| Communication skills | 1.42 (0.70–2.88) | 0.33 | |

| Internalizing behavior | 0.75 (0.44–1.27) | 0.28 | |

| Externalizing behavior | 0.97 (0.59–1.58) | 0.89 | |

| Obsessive compulsive behavior | 1.74 (0.79–3.82) | 0.17 | |

| Sickness | General Health and Wellbeing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | |||

| n (%) | p Value | Mean ± SD | p Value | |||||

| Eight weeks after discharge (n = 129) | 51 (40) | 15 (36) | 36 (41) | 0.34 | 4.3 ± 0.69 | 4.3 ± 0.63 | 4.3 ± 0.73 | 0.66 |

| Six months after birth (n = 124) | 71 (57) | 21 (54) | 50 (59) | 0.37 | 4.5 ± 0.64 | 4.7 ± 0.58 | 4.5 ± 0.67 | 0.14 |

| One year of age (n = 83) | 70 (84) | 22 (79) | 48 (87) | 0.24 | 4.6 ± 0.51 | 4.8 ± 0.44 | 4.6 ± 0.53 | 0.08 |

| Six years of age (n = 140) | 95 (68) | 29 (67) | 66 (68) | 0.55 | 4.6 ± 0.68 | 4.5 ± 0.70 | 4.6 ± 0.67 | 0.81 |

| Total | Breast Milk (n = 43) | Fortified Breast Milk and/or Formula (n = 99) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Mean ± SD | Number (%) | Mean ± SD | Number (%) | Mean ± SD | p Value for Number of Visits | p Value Visit | |

| Primary health care | 101 (72) | 4.67 ± 6.51 | 28 (65) | 3.39 ± 2.19 | 73 (75) | 5.15 ± 7.49 | 0.27 | 0.18 |

| Hospital care visit | 51 (36) | 2.37 ± 2.24 | 19 (44) | 1.85 ± 0.80 | 32 (33) | 2.68 ± 2.73 | 0.19 | 0.13 |

| Emergency visit | 88 (62) | 2.60 ± 2.56 | 27 (63) | 2.10 ± 1.64 | 61 (62) | 2.79 ± 3.00 | 0.33 | 0.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ericson, J.; Ahlsson, F.; Wackernagel, D.; Wilson, E. Equally Good Neurological, Growth, and Health Outcomes up to 6 Years of Age in Moderately Preterm Infants Who Received Exclusive vs. Fortified Breast Milk—A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102318

Ericson J, Ahlsson F, Wackernagel D, Wilson E. Equally Good Neurological, Growth, and Health Outcomes up to 6 Years of Age in Moderately Preterm Infants Who Received Exclusive vs. Fortified Breast Milk—A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2023; 15(10):2318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102318

Chicago/Turabian StyleEricson, Jenny, Fredrik Ahlsson, Dirk Wackernagel, and Emilija Wilson. 2023. "Equally Good Neurological, Growth, and Health Outcomes up to 6 Years of Age in Moderately Preterm Infants Who Received Exclusive vs. Fortified Breast Milk—A Longitudinal Cohort Study" Nutrients 15, no. 10: 2318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102318

APA StyleEricson, J., Ahlsson, F., Wackernagel, D., & Wilson, E. (2023). Equally Good Neurological, Growth, and Health Outcomes up to 6 Years of Age in Moderately Preterm Infants Who Received Exclusive vs. Fortified Breast Milk—A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Nutrients, 15(10), 2318. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15102318