Abstract

Since anthropometric measurements are not always feasible in large surveys, self-reported values are an alternative. Our objective was to assess the reliability of self-reported weight and height values compared to measured values in children with (1) a cross-sectional study in Switzerland and (2) a comprehensive review with a meta-analysis. We conducted a secondary analysis of data from a school-based study in Switzerland of 2616 children and a review of 63 published studies including 122,629 children. In the cross-sectional study, self-reported and measured values were highly correlated (weight: r = 0.96; height: r = 0.92; body mass index (BMI) r = 0.88), although self-reported values tended to underestimate measured values (weight: −1.4 kg; height: −0.9 cm; BMI: −0.4 kg/m2). Prevalence of underweight was overestimated and prevalence of overweight was underestimated using self-reported values. In the meta-analysis, high correlations were found between self-reported and measured values (weight: r = 0.94; height: r = 0.87; BMI: r = 0.88). Weight (−1.4 kg) and BMI (−0.7 kg/m2) were underestimated, and height was slightly overestimated (+0.1 cm) with self-reported values. Self-reported values tended to be more reliable in children above 11 years old. Self-reported weight and height in children can be a reliable alternative to measurements, but should be used with caution to estimate over- or underweight prevalence.

1. Introduction

Weight and height are key indicators of growth and health in children, especially in a context of rising obesity [1]. In large surveys, the measurement of weight and height is often not feasible due to financial, logistic, and human resources limitations and self-reported values are used as an alternative. Easy to collect, self-reported values are prone to misreporting [2,3]. In adults, weight tends to be underestimated and height tends to be overestimated [4,5]. As a result, body mass index (BMI) is underestimated which leads to underestimation in the prevalence of overweight and obesity [5] and to biased estimates of the risk of obesity-related health outcomes [6,7].

To evaluate how reliable self-reported weight and height values are, it is necessary to compare self-reported and measured values in the population of interest because evidence suggest that reporting bias can differ between populations depending on cultural norms [8,9,10]. Estimating the degree of reporting bias is necessary to use self-reported instead of measured values. In Switzerland, bias in the self-report of weight and height has been well documented in adults [5], but not in children and adolescents.

Our objective was therefore to assess the reliability of self-reported weight and height in a large school-based sample of children in Switzerland and to compare our findings with other studies that have assessed the reliability of self-reported weight and height in children.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. School-Based Cross-Sectional Study

2.1.1. Data Collection

We conducted a secondary analysis of a school-based cross-sectional study, that took place in the canton of Vaud, in Switzerland between September 2005 and May 2006 [11,12]. All children from sixth grade in public schools in Vaud, Switzerland were invited to participate in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Canton of Vaud (approval number 91/05). Consent was sought from the directors of the schools. Signed informed consent of the child and one parent were obtained.

The children were asked their height and weight, and were then measured with fixed stadiometers (at 0.1 cm) and with precision electronic scales (at 0.1 kg) [13]. Children were in light clothes and without shoes and measurement were made by trained clinical assistants. Basic information of the participants’ socio-economic and lifestyle characteristics (i.e., sex, physical activity, TV viewing, parental education, and parental BMI) were collected by questionnaire. The questionnaires are provided in Supplementary Table S1 of the Supplementary Material.

2.1.2. Data Analysis

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilogram (kg) divided by the squared height in meter (m). BMI z-scores were calculated based on the age- and gender-specific reference values from the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [14] and were classified into underweight (BMI z-score <−2), normal weight (BMI z-score −2 to 1) and overweight/obese (BMI z-score >1) categories. The Shapiro–Wilk test confirmed that the hypothesis that the data of the variables under study came from the normal distribution. Mean differences were calculated by subtracting measured values to self-reported values. Pearson’s r correlations were computed to estimate the correlation between self-reported and measured values. Intra-class correlations were calculated to estimate agreement between self-reported and measured values. Kappa statistics were computed to estimate the agreement between BMI categories (underweight, normal weight, and overweight). Distributions were plotted in histograms. The agreement between measures were plotted with Bland–Altman plots [15]. Differences between groups were assessed with t tests. The statistical analyses were conducted with R (version 3.6.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in the graphical user interface RAnalyticFlow (version 3.1.8, Ef-prime, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

2.2. Review

2.2.1. Data Collection

We conducted a comprehensive non-systematic review to identify other studies having assessed the reliability of self-reported weight and height in children for comparison with the results of our school-based study. Studies which assessed the reliability of self-reported weight and height in children by parents were not included. We searched for published studies comparing self-reported and measured weight and height in children in Medline using the keywords “child”, “height”, “weight”, “self-reported”, and “measured”. We completed our search by screening the reference lists of the studies included and reviews on related subjects [15,16,17,18]. Cross-sectional and cohort studies comparing self-reported and measured weight, height and BMI in apparently healthy children up to 18 years of age (mean age) were included.

2.2.2. Data Analysis

The following information were extracted: country, sample size, sex, age, measurement method, time between self-report and measure, missing data, Pearson’s r correlations, intra-class correlations, mean differences (self-reported—measured), and percentage differences between reported and measured weight, height and BMI. Data transformations and imputations were done according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [19]. When possible, data were merged and pooled reliability was estimated using random effects meta-analyses. Sub-group analyses were conducted to compare results by sex, age (6–11, 12–15, 16–21 years old), region (Asia, Australasia, Europe, Latin America, North America), knowing about subsequent measurement (whether the participants knew that they were going to be measured and weighed after reporting their weight and height), time between reported and measured values (< or ≥7 days), and self-reported data collection method (paper questionnaire, on-line questionnaire, in-person interview, telephone interview). The statistical analyses were conducted with R (version 3.6.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in the graphical user interface RAnalyticFlow (version 3.1.8, Ef-prime, Inc., Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Sectional Study

3.1.1. Participant Characteristics

Out of the 6873 children invited in the study, 5334 (78%) agreed to participate. Out of the 5334 children who participated, 2620 (49%) reported values for weight and height and 5212 (98%) had their weight and height measured. A total of 2616 (49%) children had both reported and measured weight and height values and were included in the analysis. The children who did not report weight or height did not differ to those who did in age and height, but had a higher weight (2.9 kg, 95% CI 2.2, 3.5) and a higher BMI (0.06 kg/m2, 95% CI 0.4, 0.8). The characteristics of the children included in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n = 2616).

3.1.2. Differences between Self-Reported and Measured Values

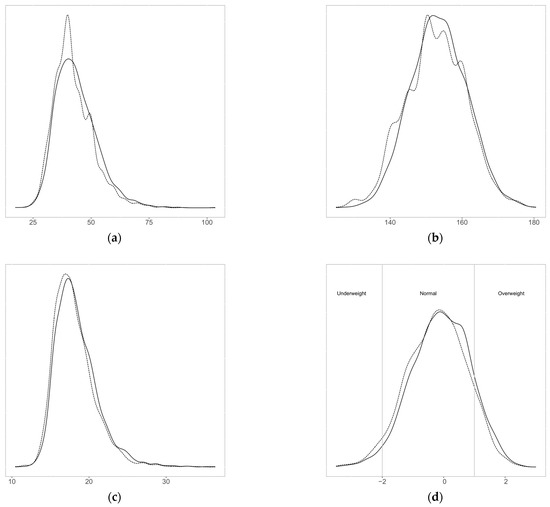

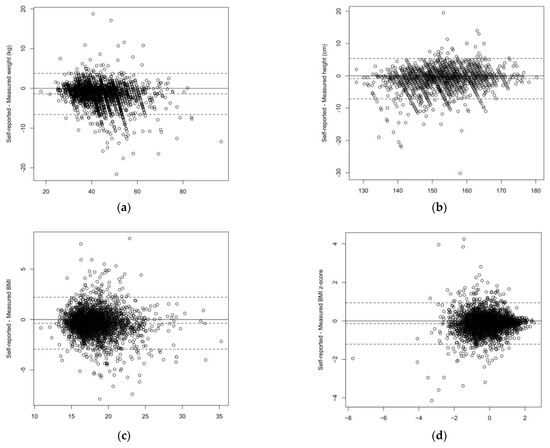

The distributions of the self-reported and measured values are shown in Figure 1 and the differences between these values are presented in Table 2. Mean self-reported weight and height were lower than measured values, by −1.4 kg (95% CI −1.5, −1.3) and −0.9 cm (95% CI −1.0, −0.8), respectively. This translated into a slightly lower mean BMI (−0.36 kg/m2; CI 95% −0.41, −0.31) and mean BMI z-scores (−0.14; 95% CI −0.16, −0.12) based on self-reported data. The Pearson correlations were 0.96 for weight, 0.92 for height, 0.88 for BMI, and 0.84 for BMI z-score. The Bland–Altman plots are shown in Figure 2. The limits of agreement (LOA) were −3.8 and 6.6 kg for weight, −5.4 and 7.1 cm for height, −2.2 and 2.9 kg/m2 for BMI, and −0.93 and 1.21 for BMI z-score.

Figure 1.

Distribution of (a) weight (kg), (b) height (cm), (c) BMI (kg/m2), and (d) BMI z-score (continuous line: measured, dashed line: self-reported).

Table 2.

Self-reported and measured weight, height, BMI and BMI z-scores, mean, mean difference, and correlations.

Figure 2.

Bland–Altman plots for (a) weight (kg), (b) height (cm), (c) BMI (kg/m2), and (d) BMI z-score (dashed lines: Mean difference and 95% confidence interval; each circle represent one individual).

Based on measured values, 85.2% of the children had a normal weight, 2.5% were underweight, and 12.2% were overweight/obese. Based on self-reported values, 85.9% of the children had a normal weight, 3.8% were underweight and 10.3% were overweight/obese. With self-reported measures, the prevalence of underweight was overestimated (+1.3%) and the prevalence of overweight was underestimated (−1.9%). The percentage of children misclassified to an incorrect BMI category as a result of inaccurate self-reported height or weight was 9.4% (n = 247). Among the children which were underweight (n = 66), 41% were incorrectly classified as normal weight (n = 27). Among the children which were overweight (n = 320), 33% were incorrectly classified as normal weight (n = 105). Among children with normal weight (n = 2230), 5% were incorrectly classified as under- or overweight (n = 115). The Cohen’s kappa for two BMI categories (non-overweight and overweight) was 0.70 and for three BMI categories (underweight, normal weight, and overweight) 0.63, which are both considered moderate agreement.

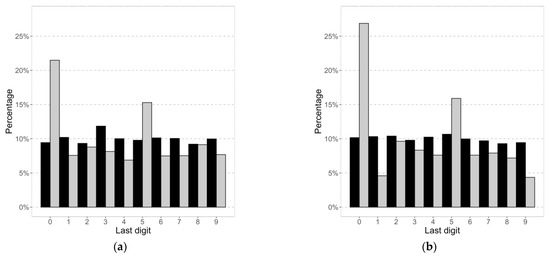

3.1.3. Digit Preferences

The distributions in Figure 1 indicated peaks of self-reported values around the 0 and 5 last digits. The distribution of the last digits is shown in Figure 3. For the measured values, every digit was reported approximately 10% of the time. The last digits 0 and 5 of the self-reported values were reported much more often, i.e., for weight 21% and 15%, respectively, and for height 27% and 16%, respectively. Rounding was done more often towards a lower value weight than towards a higher value.

Figure 3.

Distribution of last digit for (a) weight (kg) and (b) height (cm) for self-reported (white) and measured (black) values.

3.1.4. Factors Associated with Reporting

Some participant characteristics were associated with differences in reporting (Table 3). Differences in reporting were found according to BMI category: overweight/obese children underestimated more their weight in comparison with children with normal weight, and children with underweight tended to overestimate their weight in a larger magnitude. No significant differences were found for height according to BMI category.

Table 3.

Mean differences (95% CI) between self-reported and measured weight and height in difference population groups.

3.2. Review

3.2.1. Study Characteristics

A total of 63 studies (including the current study) comparing self-reported and measured weight and height in children were identified (see Table 4 and Supplementary Table S2).

Table 4.

Review of studies comparing self-reported and measured weight, height and BMI in children.

The studies included 122,629 participants who were between 6 and 21 years of age with a mean of 14 years. The studies were conducted in Europe (n = 26), North America (n = 23), Asia (n = 8), Australasia/Oceania (n = 4), and South America (n = 2).

A total of 37 studies reported percentage of non-response which ranged from 0 to 80%, with an average of approximately 25%. Among the 51 studies which reported the time between the self-reported and measured values were taken, 32 (63%) measured the values on the same day, 10 (20%) between 2 and 7 days, and the remaining (17%) between the day after and up to 6 months after the self-reported values. Among the 27 studies which reported whether the participants knew if they were going to be measured subsequently, in 12 (44%) studies the participants knew and in 15 (56%) they did not know. The self-reported values were collected by paper questionnaires in 46 (73%) studies, online questionnaires in 4 (6%) studies, in-person interview in 11 (17%) studies and phone interview in 2 (3%) studies.

The Pearson’s correlations for weight, height and BMI, respectively were reported in 33, 33 and 31 studies and ranged from 0.72 to 0.99, from 0.32 to 0.99, and from 0.49 to 0.98, respectively. The mean differences between self-reported and measured values for weight, height and BMI, respectively were reported in 45, 48, and 34 studies and ranged from −7 to 0.6 kg, −10 to 8 cm, −6.5 to 2.0 kg/m2. The differences in the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and overweight/obesity, respectively were reported in 20, 22, and 19 studies and ranged from −15% to 3%, −11% to 2%, and −11% to 13% (differences in percentage points).

Three studies included participants from specific ethnicities (i.e., Melanesian [49] and American Indians [53,54]) and showed markedly lower correlations and higher mean differences than the other included studies. A study including solely overweight children [61] also found markedly lower correlations and greater underestimation of weight. One study compared child and parental reports [52] and found that parental reports are slightly more accurate that child reports. The children reported their weight and height while at home in three studies [24,30,35]. Fourteen studies included questions on body weight perception, past weight loss efforts, and confidence in self-reported values [3,25,32,37,39,42,46,49,52,58,60,63,68,73]. Thirteen studies developed a conversion factor or equation to correct the self-reported values [32,37,42,44,49,50,51,55,57,60,63,79].

3.2.2. Meta-Analysis

The results of the meta-analysis are shown in Table 5. Self-reported weight was highly correlated with measured weight (r = 0.94), with a systematic underestimation (−1.4 kg; 95% CI −1.5, −1.2). Self-reported height showed a slightly lower, although still high, correlation with measured values (r = 0.87). In some studies, height was underestimated, while in others it was overestimated, which resulted on average in a small mean difference (0.1 cm; 95% CI 0.0, 0.1). Based on self-reported values, BMI were highly correlated with measured BMI (r = 0.87) and were on average underestimated (−0.7 kg/m2; 95%CI −1.0, −0.3).

Table 5.

Results of the meta-analyses (mean (95% CI)). p-values are for differences between sub-groups.

There were no substantial differences between boys and girls in how weight was reported, but there were for height, for which boys tended to underestimate height more than girls (−0.3 cm, 95% CI −0.5, −0.2, vs. 0.0 cm, 95% CI −0.1, 0.1). There were differences across age categories. The correlations between self-reported and measured height and BMI increased with age (6–11 years: r = 0.84, 95% CI 0.79, 0.88, and r = 0.86, 95% CI 0.82, 0.90; 12–15 years: r = 0.87, 95% CI 0.85, 0.90, and r = 0.87, 95% CI 0.86, 0.89; 16–21 years: r = 0.92, 95% CI 0.90, 0.94, and r = 0.92, 95% CI 0.90, 0.95). The mean difference between self-reported and measured height increased with age, going from under- to over-estimation (6–11 years: −0.5 cm, 12–15 years: −0.2, 16–21 years: 1.4 cm). The differences between self-reported and measured weights between age groups were not significantly different. The differences between regions were significant, suggesting that in some regions, Europe especially, the self-reported values are more reliable than in other regions.

Using the metric (kg and cm) or the imperial (lb and inch) system was not associated with the degree of bias.

When the participants knew that they were going to be weighed and measured after their self-report, they tended to report more strongly correlated values for both weight (r = 0.96 vs. 0.92) and height (r = 0.93 vs. r = 0.87) and closer values for weight (−1.1 kg vs. −1.9 kg), but not for height. Having self-reported and measured values done close together in time (less than one week vs. one week or more), resulted in smaller mean differences for weight (−1.3 vs. −2.3 kg). There were no differences in correlations between data collection methods, but there were differences in the mean differences for weight, height and BMI where the smallest differences were with in-person interviews (−0.7 kg, −0.3 cm and −0.3 kg/m2).

4. Discussion

In this large sample of children in Switzerland, self-reported weight and height were highly correlated with measured values. Self-reported weight and height tended to be lower than measured values and resulted in lower BMI. Misclassification of children in both extremes of BMI occurred, due to overestimation of weight in underweight children and underestimation in overweight children. There was a tendency to round to 0 and 5 digits. The review showed similar findings, with high correlations, and with underestimated weight and BMI, but not height. Self-reported weight and height in children can be a reliable alternative to in-person measurements but should be used with caution to estimate the prevalence of over- or underweight.

The age of the respondents plays an important role in the reliability of self-reported weight and height. Several studies reported that children 7–11 years old provided less reliable reported values than older children [21,27,29]. In our review, the correlation between the reported and measured BMI was the lowest in the age group 6–11 years. In this age group, the weight was more underestimated than in the older age groups. Height showed an interesting pattern: height under-estimated in the younger 6–11-year-olds, the most accurate in the 12–15-year-olds, and over-estimated in the older 16–21-year-olds. In the 6–11-year-olds, the children could be less capable of reporting height or likely to have undergone a growth spurt since the last time measured. In the 16–21-year-olds, the overestimation of height matches what has been found typically in adults [4,5].

The reliability of self-reported values differed slightly across regions. Hence, the reliability of self-reported values tended to be higher in European regions, and this is consistent with the results of our study in Switzerland. One might also hypothesize that the differences between regions found in the meta-analysis could be explained by differences in body image in different cultures and by the inclusion of some studies in certain regions (i.e., North America and Australasia/Oceania) with especially low reliability due to participants’ characteristics. In fact, in some low-resources populations or in studies including a large share of children of low socio-economic background [49,53,54], participants could have been weighed and measured less often, and therefore less aware of their weight and height. Moreover, in populations with a high prevalence of overweight/obesity and/or underweight, self-reported values could be on average less reliable, because overweight and underweight children are more likely to misreport their weight, as also shown in the current Swiss study and review.

The design of the study also affected the reliability of reporting. In fact, children who knew that they were going to be measured afterwards, reported more accurate values. They perceived that misreporting would be discovered. Children who underwent in-person interviews also reported more accurate values. They probably perceived that the person interviewing could guess by seeing them whether misreporting occurred. In the present Swiss study, the children answered paper questionnaires and knew that they were going to be measured afterwards.

In the present study, conducted in Switzerland, rounding towards the end digits zero and five was found likewise in adults [8]. One study suggested that the effect of rounding could be bigger using the imperial rather than the metric system [58]. However, differences in reporting bias between imperial and the metric system were not found in our review. We hypothesized that rounding towards certain digits could differ between cultures (e.g., 4 and 7), but we have not found any literature on the subject.

One major issue with self-reported values in children is the high percentage of non-reporting, with the proportion of non-reporting largely different from one study to the other. We can hypothesize two reasons for non-reporting: not knowing the values or not answering to avoid stigma, especially in underweight and overweight children [3,21,34,37]. Younger children less frequently know their weight and height compared to older children [21,34]. In our study, children with missing self-reported values tended to be more overweight than those with complete values. Some researchers have tried to address this issue by imputing missing values and were able to provide more accurate estimates of the prevalence of overweight [2].

To overcome the previous limitations, several studies have proposed correction equations to improve the reliability of self-reported values [32,37,44,49,50,51,55,57,60,79]. Some included a variable on the body perception (e.g., too thin, just right, too fat) [32,49,60]. A study included two questions (on perceived ability to report weight/height and weighing/measuring history) to identify children with low response capability [3]. As children grow rapidly and undergo growth spurts, if the last time the child was measured or weighed occurred some time ago, the self-reported values could be less reliable. Another study suggested that, if questionnaires are completed at home, children could be advised to weighed themselves and be measured before answering if they are unsure [58,77]. A study suggested that adding the parent’s report on their child’s weight and height could be helpful [52]. Weight loss history is another variable which could be useful [58]. We found one study that corrected for missing values [2], but none that corrected for rounding.

Our school-based cross-sectional study has several strengths. It included many children through a school-based recruitment which covers nearly all children in the region (96% of the children attend school), and self-reported and measured values were collected on the same day. A limitation of this study is that it collected neither information on body image perception, which could have been useful to develop a correction factor for the self-reported values nor on how reliable the participants thought their self-reported values were. Another limitation of this study is that the samples consisted of children from one region in Switzerland, a country with high resources. The results of this study might therefore not be applicable to less affluent regions of the world or in younger children. However, thanks to the accompanying extensive review, we were able to put the results in context of other studies.

The strengths of this review were the inclusion of a number of studies worldwide and the multiple sub-group meta-analysis, allowing the identification of the population and study characteristics that ensure the best reliability of self-reported values. We did not identify any other reviews that also compared the correlations and mean differences between self-reported and measured anthropometrics in children and adolescents worldwide. One review compared these measures among children in studies conducted in the United States [18]. Two other reviews compared measures among children in studies conducted worldwide, but only to estimate how reliable was the prevalence and diagnosis of overweight and obesity [16,17]. Although our review was not systematic, it was comprehensive and included more studies than the previous reviews on related subjects [15,16,17,18].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, self-reported weight and height in children can be a cheap and reliable alternative to in-person measurements. The reliability of self-reported values can be increased using correction equations that include for example time since last weighed/measured, confidence in reported values, perceived body image, parental report, weight loss history. This can be especially useful in specific groups of children (younger, underweight and overweight children) that are known to provide less reliable or more missing self-reported values and for the estimation of the prevalence of over- and underweight.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu15010075/s1, Table S1: Questionnaire; Table S2: Overview of the studies identified and their key results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, M.R.-L. and A.C..; software, analysis, and data curation, M.R.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-L.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and N.O.; visualization, M.R.-L.; supervision, A.C.; project administration, A.C.; funding acquisition, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The cross-sectional study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant number 109999). NO was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant number 204967).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the review are provided in Supplementary Table S2 of the the Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide Trends in Body-Mass Index, Underweight, Overweight, and Obesity from 1975 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 2416 Population-Based Measurement Studies in 128·9 Million Children, Adolescents, and Adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, K.M.; Longacre, M.R.; Dalton, M.A.; Langeloh, G.; Peterson, K.E.; Titus, L.J.; Beach, M.L. Two-Method Measurement for Adolescent Obesity Epidemiology: Reducing the Bias in Self-Report of Height and Weight. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.; Holstein, B.E.; Melkevik, O.; Damsgaard, M.T. Validity of Self-Reported Height and Weight among Adolescents: The Importance of Reporting Capability. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorber, S.C.; Tremblay, M.; Moher, D.; Gorber, B. A Comparison of Direct vs. Self-Report Measures for Assessing Height, Weight and Body Mass Index: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faeh, D.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Chiolero, A.; Bopp, M. Obesity in Switzerland: Do Estimates Depend on How Body Mass Index Has Been Assessed? Swiss Med. Wkly. 2008, 138, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiolero, A.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Paccaud, F. Associations between Obesity and Health Conditions May Be Overestimated If Self-Reported Body Mass Index Is Used. Obes. Rev. 2007, 8, 373–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flegal, K.M.; Kit, B.K.; Graubard, B.I. Bias in Hazard Ratios Arising From Misclassification According to Self-Reported Weight and Height in Observational Studies of Body Mass Index and Mortality. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 187, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bopp, M.; Faeh, D. End-Digits Preference for Self-Reported Height Depends on Language. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkshoorn, H.; Ujcic-Voortman, J.K.; Viet, L.; Verhoeff, A.P.; Uitenbroek, D.G. Ethnic Variation in Validity of the Estimated Obesity Prevalence Using Self-Reported Weight and Height Measurements. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brestoff, J.R.; Perry, I.J.; Van den Broeck, J. Challenging the Role of Social Norms Regarding Body Weight as an Explanation for Weight, Height, and BMI Misreporting Biases: Development and Application of a New Approach to Examining Misreporting and Misclassification Bias in Surveys. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolero, A.; Cachat, F.; Burnier, M.; Paccaud, F.; Bovet, P. Prevalence of Hypertension in Schoolchildren Based on Repeated Measurements and Association with Overweight. J. Hypertens. 2007, 25, 2209–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasserre, A.M.; Chiolero, A.; Cachat, F.; Paccaud, F.; Bovet, P. Overweight in Swiss Children and Associations with Children’s and Parents’ Characteristics. Obesity 2007, 15, 2912–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Expert Committee (Ed.) Physical Status: The Use and Interpretation of Anthropometry: Report of a WHO Expert Committee; WHO Technical Report Series; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995; ISBN 978-92-4-120854-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczmarski, R.J.; Ogden, C.L.; Guo, S.S.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M.; Flegal, K.M.; Mei, Z.; Wei, R.; Curtin, L.R.; Roche, A.F.; Johnson, C.L. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. Vital Health Stat. 11 2002, 1–190. [Google Scholar]

- Flegal, K.M.; Graubard, B.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. Use and Reporting of Bland-Altman Analyses in Studies of Self-Reported versus Measured Weight and Height. Int. J. Obes. 2020, 44, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cai, Z.; Fan, X. Accuracy of Using Self-Reported Data to Screen Children and Adolescents for Overweight and Obesity Status: A Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 11, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Cai, Z.; Fan, X. How Accurate Is the Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents Derived from Self-Reported Data? A Meta-Analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, B.; Jefferds, M.E.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Accuracy of Adolescent Self-Report of Height and Weight in Assessing Overweight Status: A Literature Review. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 1154–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aasvee, K.; Rasmussen, M.; Kelly, C.; Kurvinen, E.; Giacchi, M.V.; Ahluwalia, N. Validity of Self-Reported Height and Weight for Estimating Prevalence of Overweight among Estonian Adolescents: The Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children Study. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalkhail, B.A.; Shawky, S.; Soliman, N.K. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Height among Saudi School Children and Adolescents. Saudi Med. J. 2002, 23, 831–837. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, S.; Luscombe, G.; Boyd, C.; Olesen, I. Predictors of the Accuracy of Self-Reported Height and Weight in Adolescent Female School Students. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 36, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosi-Randić, N.; Bulian, A.P. Self-Reported versus Measured Weight and Height by Adolescent Girls: A Croatian Sample. Percept. Mot. Skills 2007, 104, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.F.; Lillegaard, I.T.L.; Øverby, N.; Lytle, L.; Klepp, K.-I.; Johansson, L. Overweight and Obesity among Norwegian Schoolchildren: Changes from 1993 to 2000. Scand. J. Public Health 2005, 33, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.; Joung, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwon, K.N.; Kim, Y.; Park, S.W. Validity of Self-Reported Height, Weight, and Body Mass Index of the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-Based Survey Questionnaire. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2010, 43, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baile, J.I.; González-Calderón, M.J. Accuracy of body mass index derived from self-reported height and weight in a spanish sample of children. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 29, 829–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Schaefer, C.A.; Nace, H.; Steffen, A.D.; Nigg, C.; Brink, L.; Hill, J.O.; Browning, R.C. Accuracy of Self-Reported Height and Weight in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Béghin, L.; Huybrechts, I.; Ortega, F.B.; Coopman, S.; Manios, Y.; Wijnhoven, T.M.A.; Duhamel, A.; Ciarapica, D.; Gilbert, C.C.; Kafatos, A.; et al. Nutritional and Pubertal Status Influences Accuracy of Self-Reported Weight and Height in Adolescents: The HELENA Study. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 62, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, I.M.; Simonsson, B.; Brantefor, B.; Ringqvist, I. Prevalence of Overweight and Obesity in Children and Adolescents in a County in Sweden. Acta Paediatr. 2001, 90, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, M.-C.; Turcotte, O.; Aimé, A.; Côté, M.; Bégin, C. Body Mass Index Accuracy in Preadolescents: Can We Trust Self-Report or Should We Seek Parent Report? J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N.D.; Mcmanus, T.; Galuska, D.A.; Lowry, R.; Wechsler, H. Reliability and Validity of Self-Reported Height and Weight among High School Students. J Adolesc. Health 2003, 32, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brettschneider, A.-K.; Schaffrath Rosario, A.; Wiegand, S.; Kollock, M.; Ellert, U. Development and Validation of Correction Formulas for Self-Reported Height and Weight to Estimate BMI in Adolescents. Results from the KiGGS Study. Obes. Facts 2015, 8, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks-Gunn, J.; Warren, M.P.; Rosso, J.; Gargiulo, J. Validity of Self-Report Measures of Girls’ Pubertal Status. Child Dev. 1987, 58, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttenheim, A.M.; Goldman, N.; Pebley, A.R. Underestimation of Adolescent Obesity. Nurs. Res. 2013, 62, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, N.P.T.; Choi, K.C.; Nelson, E.A.S.; Sung, R.Y.T.; Chan, J.C.N.; Kong, A.P.S. Self-Reported Body Weight and Height: An Assessment Tool for Identifying Children with Overweight/Obesity Status and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors Clustering. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalampos, H.; Michael, T.; Antonia, S.; Savva, S.; Antonis, K. Validity of Self-Reported Height, Weight and Body Mass Index among Cypriot Adolescents: Accuracy in Assessing Overweight Status and Weight Overestimation as Predictor of Disordered Eating Behaviour. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, N.; Chau, K.; Mayet, A.; Baumann, M.; Legleye, S.; Falissard, B. Self-Reporting and Measurement of Body Mass Index in Adolescents: Refusals and Validity, and the Possible Role of Socioeconomic and Health-Related Factors. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.; Sastry, N.; Duffy, D.; Ailshire, J. Accuracy of Self-Reported versus Measured Weight over Adolescence and Young Adulthood: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, 1996–2008. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dalton, W.T.; Wang, L.; Southerland, J.L.; Schetzina, K.E.; Slawson, D.L. Self-Reported Versus Actual Weight and Height Data Contribute to Different Weight Misperception Classifications. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H.; Gergen, P.J. The Weights and Heights of Mexican-American Adolescents: The Accuracy of Self-Reports. Am. J. Public Health 1994, 84, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Vriendt, T.; Huybrechts, I.; Ottevaere, C.; Van Trimpont, I.; De Henauw, S. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Height of Adolescents, Its Impact on Classification into BMI-Categories and the Association with Weighing Behaviour. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2696–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, A.P.; Silva, A.M.; de Matos, M.M.N.G.; Calmeiro, L. Accuracy of Self-Reported Measures of Height and Weight in Children and Adolescents. Rev. Psicol. Criança Adolesc. 2011, 2, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, S.; Kull, I.; Nilsson, S.; Bergström, A. Web-Based Self-Reported Height, Weight, and Body Mass Index among Swedish Adolescents: A Validation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2015, 17, e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgar, F.J.; Roberts, C.; Tudor-Smith, C.; Moore, L. Validity of Self-Reported Height and Weight and Predictors of Bias in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 37, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enes, C.C.; Fernandez, P.M.F.; Voci, S.M.; Toral, N.; Romero, A.; Slater, B. Validity and Reliability of Self-Reported Weight and Height Measures for the Diagnoses of Adolescent’s Nutritional Status. Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2009, 12, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré Rovira, R.; Frasquet Pons, I.; Martínez Martínez, M.I.; Romá Sánchez, R. Self-Reported versus Measured Height, Weight and Body Mass Index in Spanish Mediterranean Teenagers: Effects of Gender, Age and Weight on Perceptual Measures of Body Image. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2002, 46, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, H.; Silva, A.M.; Matos, M.G.; Esteves, I.; Costa, P.; Guerra, A.; Gomes-Pedro, J. Validity of BMI Based on Self-Reported Weight and Height in Adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortenberry, J.D. Reliability of Adolescents’ Reports of Height and Weight. J. Adolesc. Health 1992, 13, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayon, S.; Cavaloc, Y.; Wattelez, G.; Cherrier, S.; Lerrant, Y.; Galy, O. Self-Reported Height and Weight in Oceanian School-Going Adolescents and Factors Associated With Errors. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2017, 29, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh-Dastidar, M.B.; Haas, A.C.; Nicosia, N.; Datar, A. Accuracy of BMI Correction Using Multiple Reports in Children. BMC Obes. 2016, 3, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacchi, M.; Mattei, R.; Rossi, S. Correction of the Self-Reported BMI in a Teenage Population. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1998, 22, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, E.; Hinden, B.R.; Khandelwal, S. Accuracy of Teen and Parental Reports of Obesity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics 2000, 106, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauck, F.R.; White, L.; Cao, G.; Woolf, N.; Strauss, K. Inaccuracy of Self-Reported Weights and Heights among American Indian Adolescents. Ann. Epidemiol. 1995, 5, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himes, J.H.; Story, M. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Stature of American Indian Youth. J. Adolesc. Health 1992, 13, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himes, J.H.; Faricy, A. Validity and Reliability of Self-Reported Stature and Weight of US Adolescents. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2001, 13, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himes, J.H.; Hannan, P.; Wall, M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Factors Associated with Errors in Self-Reports of Stature, Weight, and Body Mass Index in Minnesota Adolescents. Ann. Epidemiol. 2005, 15, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, W.; van de Looij-Jansen, P.M.; Ferreira, I.; de Wilde, E.J.; Brug, J. Differences in Measured and Self-Reported Height and Weight in Dutch Adolescents. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2006, 50, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardene, W.; Lohrmann, D.; YoussefAgha, A. Discrepant Body Mass Index: Behaviors Associated with Height and Weight Misreporting among US Adolescents from the National Youth Physical Activity and Nutrition Study. Child Obes. 2014, 10, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, C.C.; Lim, K.H.; Sumarni, M.G.; Teh, C.H.; Chan, Y.Y.; Nuur Hafizah, M.I.; Cheah, Y.K.; Tee, E.O.; Ahmad Faudzi, Y.; Amal Nasir, M. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Height: A Cross-Sectional Study among Malaysian Adolescents. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2017, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, B.-M.; Ellert, U. Estimated and Measured BMI and Self-Perceived Body Image of Adolescents in Germany: Part 1—General Implications for Correcting Prevalence Estimations of Overweight and Obesity. Obes. Facts 2010, 3, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Valeria, B.; Kochman, C.; Lenders, C.M. Self-Assessment of Height, Weight, and Sexual Maturation: Validity in Overweight Children and Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 39, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Chung, S.-J.; Lee, S.-K.; Yoon, J. Validation of Self-Reported Height and Weight in Fifth-Grade Korean Children. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2013, 7, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Legleye, S.; Beck, F.; Spilka, S.; Chau, N. Correction of Body-Mass Index Using Body-Shape Perception and Socioeconomic Status in Adolescent Self-Report Surveys. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linhart, Y.; Romano-Zelekha, O.; Shohat, T. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Height among 13–14 Year Old Schoolchildren in Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 12, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, S.L.; Whetstone, L.M.; Cummings, D.M.; Owen, L.J. Comparison of Self-Reported and Measured Height and Weight in Eighth-Grade Students. J. Sch. Health 2006, 76, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlmer, R.; Jacobi, C.; Fittig, E. Diagnosing Underweight in Adolescent Girls: Should We Rely on Self-Reported Height and Weight? Eat. Behav. 2012, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, A.; Gabriel, K.P.; Nehme, E.K.; Mandell, D.J.; Hoelscher, D.M. Measuring the Bias, Precision, Accuracy, and Validity of Self-Reported Height and Weight in Assessing Overweight and Obesity Status among Adolescents Using a Surveillance System. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, F.; Eriksson, M.; Nordquist, T. Bias in Height and Weight Reported by Swedish Adolescents and Relations to Body Dissatisfaction: The COMPASS Study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robinson, L.E.; Suminski, R. Accuracy of Self-Reported Height and Weight in Low-Income, Rural African American Children. J. Child Adolesc. Behav. 2014, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.R.M.; Gonçalves-Silva, R.M.V.; Pereira, R.A. Validity of Self-Reported Weight and Stature in Adolescents from Cuiabá, Central-Western Brazil. Rev. Nutr. 2013, 26, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Seghers, J.; Claessens, A.L. Bias in Self-Reported Height and Weight in Preadolescents. J. Pediatr. 2010, 157, 911–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefan, L.; Baić, M.; Pekas, D. Validity of Measured vs. Self-Reported Height, Weight and Body-Mass Index in Urban Croatian Adolescents. Int. J. Sport Stud. Health, 2019; 2, e89627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, R.S. Comparison of Measured and Self-Reported Weight and Height in a Cross-Sectional Sample of Young Adolescents. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1999, 23, 904–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tienboon, P.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Rutishauser, I.H. Self-Reported Weight and Height in Adolescents and Their Parents. J. Adolesc. Health 1992, 13, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokmakidis, S.P.; Christodoulos, A.D.; Mantzouranis, N.I. Validity of Self-Reported Anthropometric Values Used to Assess Body Mass Index and Estimate Obesity in Greek School Children. J. Adolesc. Health 2007, 40, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsigilis, N. Can Secondary School Students’ Self-Reported Measures of Height and Weight Be Trusted? An Effect Size Approach. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Patterson, C.M.; Hills, A.P. A Comparison of Self-Reported and Measured Height, Weight and BMI in Australian Adolescents. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2002, 26, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshitake, N.; Okuda, M.; Sasaki, S.; Kunitsugu, I.; Hobara, T. Validity of Self-Reported Body Mass Index of Japanese Children and Adolescents. Pediatr. Int. 2012, 54, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Dibley, M.J.; Cheng, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Yan, H. Validity of Self-Reported Weight, Height and Resultant Body Mass Index in Chinese Adolescents and Factors Associated with Errors in Self-Reports. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).