Vitamin E Intake and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

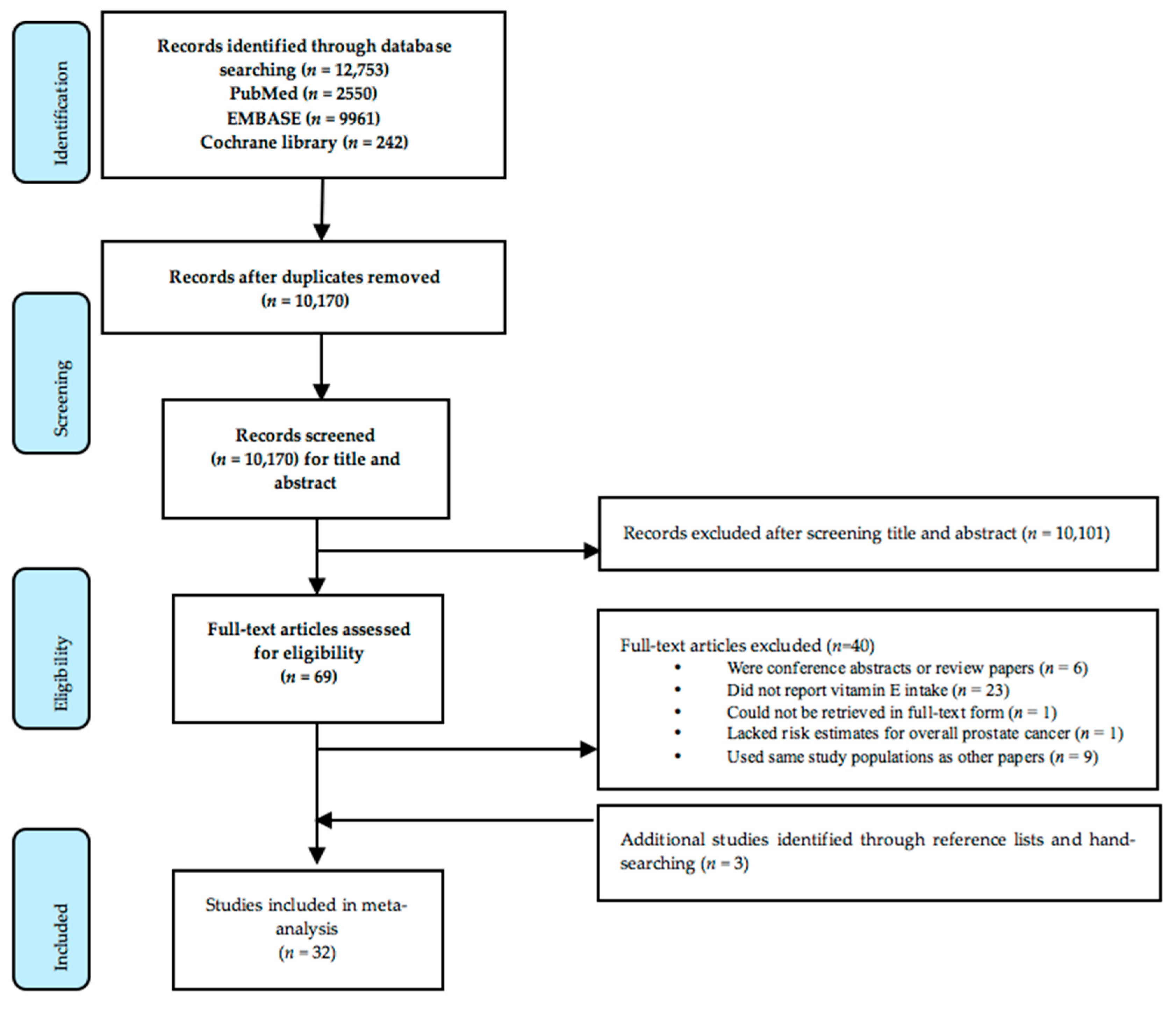

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

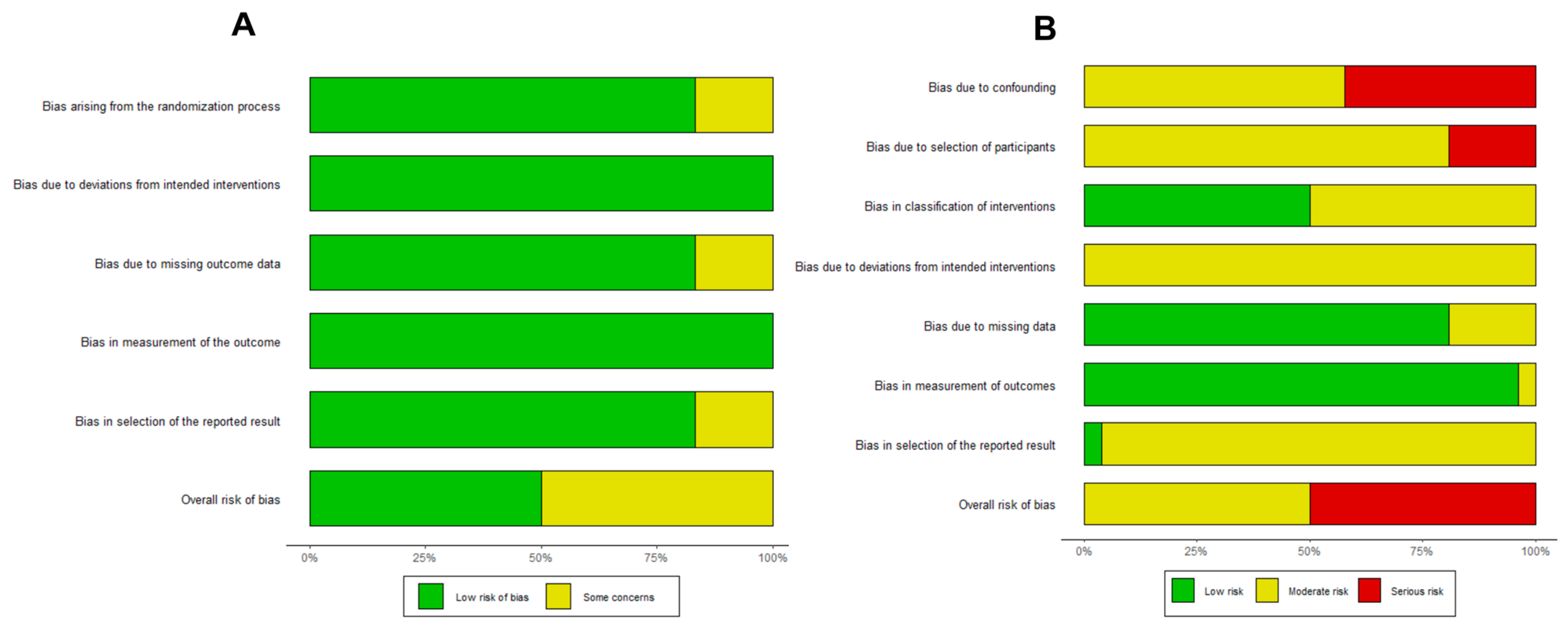

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Studies Selected

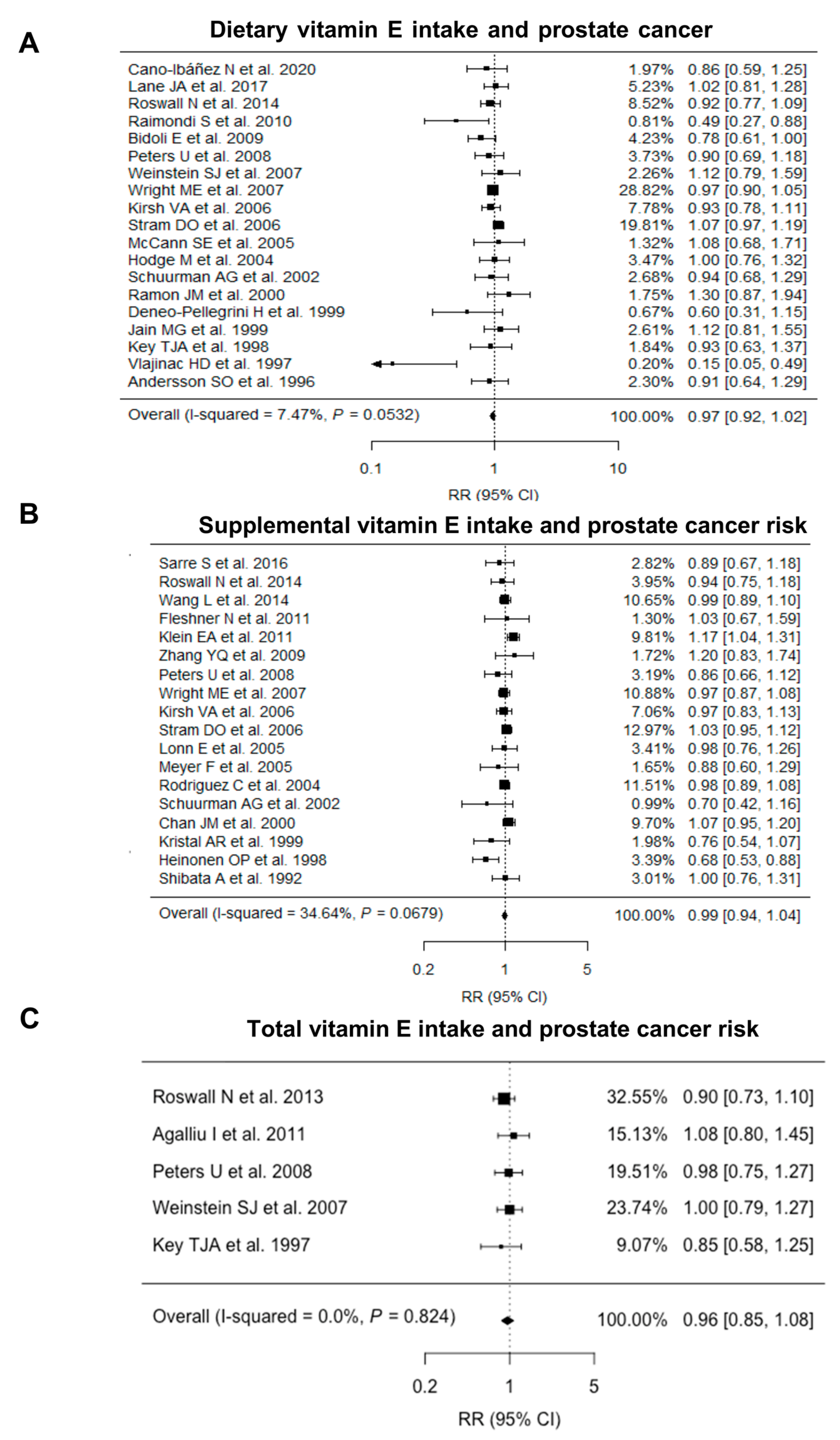

3.2. Overall Analysis of Vitamin E Intake and Prostate Cancer

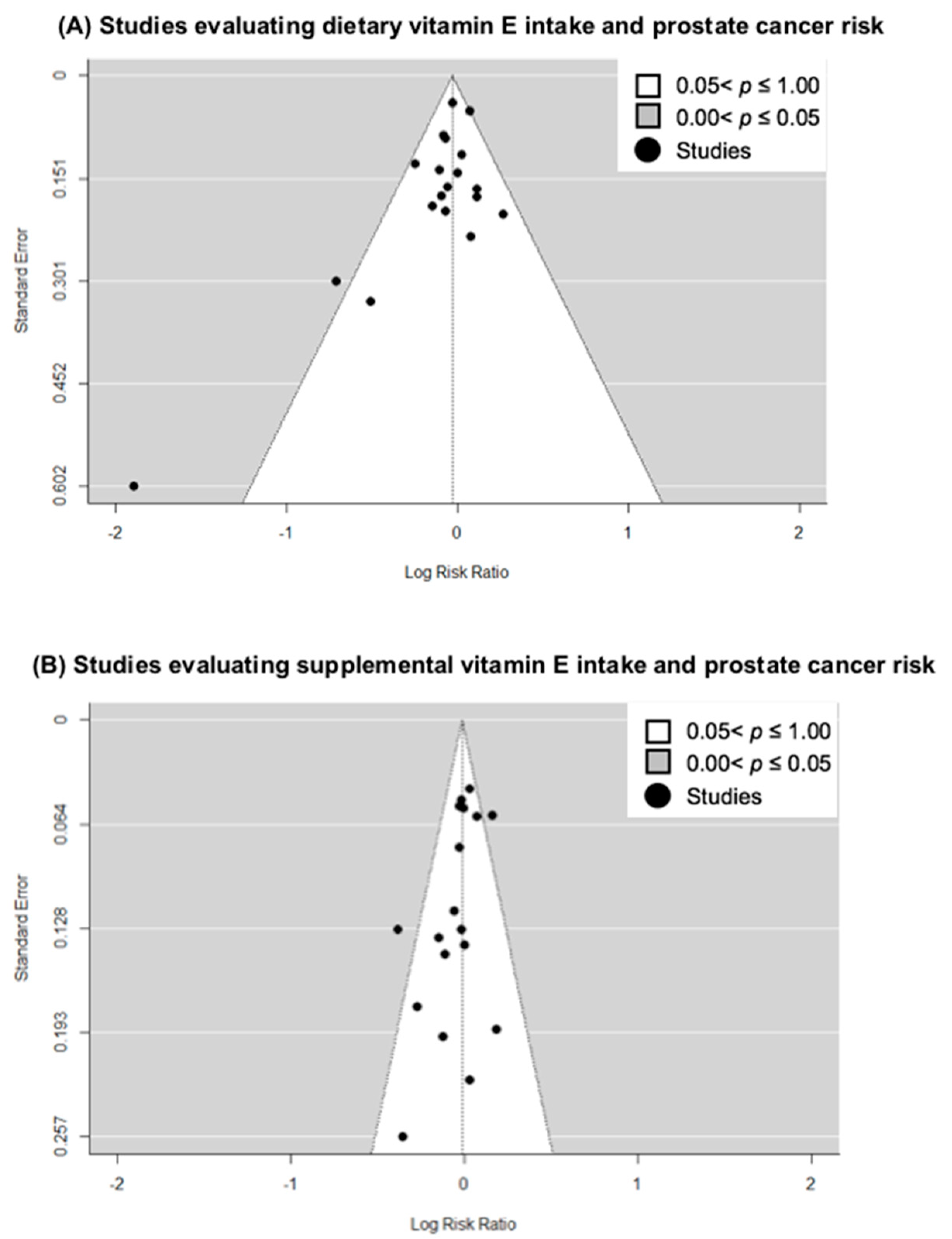

3.3. Small-Study Effects and Quality Analysis

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

3.5. Subgroup Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grozescu, T.; Popa, F. Prostate cancer between prognosis and adequate/proper therapy. J. Med. Life 2017, 10, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Pinaffi-Langley, A.C.C.; Fuentes, J.; Speisky, H.; de Camargo, A.C. Vitamin E as an essential micronutrient for human health: Common, novel, and unexplored dietary sources. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 176, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonovas, S.; Tsantes, A.; Drosos, T.; Sitaras, N.M. Cancer Chemoprevention: A Summary of the Current Evidence. Anticancer. Res. 2008, 28, 1857–1966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, C.; Kaneko, J.; Sato, A.; Virgona, N.; Namiki, K.; Yano, T. Combination Effect of d-Tocotrienol and g-Tocopherol on Prostate Cancer Cell Growth. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2017, 63, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; He, Y.; Cui, X.X.; Goodin, S.; Wang, H.; Du, Z.Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, K.; Tony Kong, A.N.; DiPaola, R.S.; et al. Potent inhibitory effect of delta-tocopherol on prostate cancer cells cultured in vitro and grown as xenograft tumors in vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 10752–10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinonen, O.P.; Albanes, D.; Virtamo, J.; Taylor, P.R.; Huttunen, J.K.; Hartman, A.M.; Haapakoski, J.; Malila, N.; Rautalahti, M.; Ripatti, S.; et al. Prostate Cancer and Supplementation With α-Tocopherol and β-Carotene: Incidence and Mortality in a Controlled Trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998, 90, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; Galan, P.; Douville, P.; Bairati, I.; Kegle, P.; Bertrais, S.; Estaquio, C.; Hercberg, S. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplementation and prostate cancer prevention in the SU.VI.MAX trial. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 116, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sesso, H.D.; Glynn, R.J.; Christen, W.G.; Bubes, V.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Gaziano, J.M. Vitamin E and C supplementation and risk of cancer in men: Posttrial follow-up in the Physicians’ Health Study II randomized trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.A.; Thompson, I.M., Jr.; Tangen, C.M.; Crowley, J.J.; Lucia, M.S.; Goodman, P.J.; Minasian, L.M.; Ford, L.G.; Parnes, H.L.; Gaziano, J.M.; et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA 2011, 306, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleshner, N.E.; Kapusta, L.; Donnelly, B.; Tanguay, S.; Chin, J.; Hersey, K.; Farley, A.; Jansz, K.; Siemens, D.R.; Trpkov, K.; et al. Progression from high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia to cancer: A randomized trial of combination vitamin-E, soy, and selenium. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2386–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonn, E.; Bosch, J.; Yusuf, S.; Sheridan, P.; Pogue, J.; Arnold, J.M.O.; Ross, C.; Arnold, A.; Sleight, P.; Probstfield, J.; et al. Effects of Long-term Vitamin E Supplementation on Cardiovascular Events and Cancer. JAMA 2005, 293, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stratton, J.; Godwin, M. The effect of supplemental vitamins and minerals on the development of prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam. Pract. 2011, 28, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhenizan, A.; Hafez, K. The role of vitamin E in the prevention of cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann. Saudi. Med. 2007, 27, 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zaaboul, F.; Liu, Y. Vitamin E in foodstuff: Nutritional, analytical, and food technology aspects. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 964–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skeie, G.; Braaten, T.; Hjartaker, A.; Lentjes, M.; Amiano, P.; Jakszyn, P.; Pala, V.; Palanca, A.; Niekerk, E.M.; Verhagen, H.; et al. Use of dietary supplements in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition calibration study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63 (Suppl. S4), S226–S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, E.S.; Ajani, U.A.; Mokdad, A.H. Brief Communication: The Prevalence of High Intake of Vitamin E. from the Use of Supplements among U.S. Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; Group, P.-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernan, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savovic, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, A.; Discacciati, A.; Bottai, M.; Spiegelman, D.; Orsini, N. One-stage dose-response meta-analysis for aggregated data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 1579–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, A.; Orsini, N. Multivariate Dose-Response Meta-Analysis: ThedosresmetaRPackage. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 72, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.R.; Lee, J. Dose-response meta-analysis: Application and practice using the R software. Epidemiol Health 2019, 41, e2019006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. Conducting Meta-Analyses in R with the metafor Package. J. Stat. Softw. 2010, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ibanez, N.; Barrios-Rodriguez, R.; Lozano-Lorca, M.; Vazquez-Alonso, F.; Arrabal-Martin, M.; Trivino-Juarez, J.M.; Salcedo-Bellido, I.; Jimenez-Moleon, J.J.; Olmedo-Requena, R. Dietary Diversity and Prostate Cancer in a Spanish Adult Population: CAPLIFE Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.A.; Oliver, S.E.; Appleby, P.N.; Lentjes, M.A.; Emmett, P.; Kuh, D.; Stephen, A.; Brunner, E.J.; Shipley, M.J.; Hamdy, F.C.; et al. Prostate cancer risk related to foods, food groups, macronutrients and micronutrients derived from the UK Dietary Cohort Consortium food diaries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 71, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarre, S.; Maattanen, L.; Tammela, T.L.; Auvinen, A.; Murtola, T.J. Postscreening follow-up of the Finnish Prostate Cancer Screening Trial on putative prostate cancer risk factors: Vitamin and mineral use, male pattern baldness, pubertal development and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Scand J. Urol. 2016, 50, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roswall, N.; Larsen, S.B.; Friis, S.; Outzen, M.; Olsen, A.; Christensen, J.; Dragsted, L.O.; Tjonneland, A. Micronutrient intake and risk of prostate cancer in a cohort of middle-aged, Danish men. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 1129–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agalliu, I.; Kirsh, V.A.; Kreiger, N.; Soskolne, C.L.; Rohan, T.E. Oxidative balance score and risk of prostate cancer: Results from a case-cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011, 35, 353–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondi, S.; Mabrouk, J.B.; Shatenstein, B.; Maisonneuve, P.; Ghadirian, P. Diet and prostate cancer risk with specific focus on dairy products and dietary calcium: A case-control study. Prostate 2010, 70, 1054–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidoli, E.; Talamini, R.; Zucchetto, A.; Bosetti, C.; Negri, E.; Lenardon, O.; Maso, L.D.; Polesel, J.; Montella, M.; Franceschi, S.; et al. Dietary vitamins E and C and prostate cancer risk. Acta Oncol. 2009, 48, 890–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, U.; Littman, A.J.; Kristal, A.R.; Patterson, R.E.; Potter, J.D.; White, E. Vitamin E and selenium supplementation and risk of prostate cancer in the Vitamins and lifestyle (VITAL) study cohort. Cancer Causes Control 2008, 19, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Coogan, P.; Palmer, J.R.; Strom, B.L.; Rosenberg, L. Vitamin and mineral use and risk of prostate cancer: The case-control surveillance study. Cancer Causes Control 2009, 20, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, S.J.; Wright, M.E.; Lawson, K.A.; Snyder, K.; Mannisto, S.; Taylor, P.R.; Virtamo, J.; Albanes, D. Serum and dietary vitamin E in relation to prostate cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.E.; Weinstein, S.J.; Lawson, K.A.; Albanes, D.; Subar, A.F.; Dixon, L.B.; Mouw, T.; Schatzkin, A.; Leitzmann, M.F. Supplemental and dietary vitamin E intakes and risk of prostate cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2007, 16, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsh, V.A.; Hayes, R.B.; Mayne, S.T.; Chatterjee, N.; Subar, A.F.; Dixon, L.B.; Albanes, D.; Andriole, G.L.; Urban, D.A.; Peters, U.; et al. Supplemental and dietary vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C intakes and prostate cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stram, D.O.; Hankin, J.H.; Wilkens, L.R.; Park, S.; Henderson, B.E.; Nomura, A.M.; Pike, M.C.; Kolonel, L.N. Prostate cancer incidence and intake of fruits, vegetables and related micronutrients: The multiethnic cohort study* (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2006, 17, 1193–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, S.E.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Moysich, K.B.; Brasure, J.; Marshall, J.R.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Wilkinson, G.S.; Graham, S. Intakes of selected nutrients, foods, and phytochemicals and prostate cancer risk in western New York. Nutr. Cancer 2005, 53, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodge, A.M.; English, D.R.; McCredie, M.R.E.; Severi, G.; Boyle, P.; Hopper, J.L.; Giles, G.G. Foods, nutrients and prostate cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2004, 15, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.; Jacobs, E.J.; Mondul, A.M.; Calle, E.E.; McCullough, M.L.; Thun, M.J. Vitamin E Supplements and Risk of Prostate Cancer in U.S. Men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, A.G.; Goldbohm, A.; Brants, H.A.M.; van den Brandt, P.A. A prospective cohort study on intake of retinol, vitamins C and E, and carotenoids and prostate cancer risk (Netherlands). Cancer Causes Cotnrol 2002, 13, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramon, J.M.; Bou, R.; Romea, S.; Alkiza, M.E.; Jacas, M. Dietary fat intake and prostate cancer risk: A case-control study in Spain. Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 679–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.M.; Pitinen, P.; Virtanen, M.; Malila, N.; Tangrea, J.; Albanes, D.; Virtamo, J. Diet and prostate cancer risk in a cohort of smokers, with a specific focus on calcium and phosphorus (Finland). Cancer Causes Control 2000, 11, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Stefani, E.D.; Ronco, A.; Medilaharsu, M. Foods, nutrients and prostate cancer: A caseÐcontrol study in Uruguay. Br. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.G.; Hislop, G.T.; Howe, G.R.; Ghadirian, P. Plant foods, antioxidants, and prostate cancer risk: Findings from case-control studies in Canada. Nutr. Cancer 1999, 34, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristal, A.R.; Stanford, J.L.; Cohen, J.H.; Wicklund, K.; Patterson, R.E. Vitamin and Mineral Supplement Use Is Associated with Reduced Risk of Prostate Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1999, 8, 887–892. [Google Scholar]

- Key, T.J.A.; Silcocks, P.B.; Davey, G.K.; Appleby, P.N.; Bishop, D.T. A case-control study of diet and prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 1997, 76, 678–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlajinac, H.D.; Marinkovic, J.M.; Ilic, M.D.; Kocev, N.I. Diet and Prostate Cancer: A Case-Control Study. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.O.; Wolk, A.; Giovannucci, E.; Bergström, R.; Lindgren, C.; Baron, J.A.; Adami, H.O. Energy, Nutrient intake and Prostate Cancer Risk: A population-Based Case-Control STudy in Sweden. Int. J. Cancer 1996, 68, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, A.; Paganini-Hill, A.; Ross, R.K.; Henderson, B.E. Intake of vegetables, fruits, beta-carotene, vitamin C and vitamin supplements and cancer incidence among the elderly: A prospective study. Br. J. Cancer 1992, 66, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marianna, S.; Katarina, F.-S.; Eva, T.; Miroslava, K. Vitamin E: Recommended Intake. In Vitamin E in Health and Disease; Pınar, E., Júlia Scherer, S., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Allen, N.E.; Travis, R.C.; Roddam, A.W.; Jenab, M.; Egevad, L.; Tjønneland, A.; Johnsen, N.F.; Overvad, K.; et al. Plasma carotenoids, retinol, and tocopherols and the risk of prostate cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 86, 672–681. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R.; Liu, Z.Q.; Xu, Q. Blood alpha-tocopherol, gamma-tocopherol levels and risk of prostate cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 2014, 9, e93044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, H.; Preziosi, P.; Roussel, A.M.; Bertrais, S.; Galan, P.; Hercberg, S.; Favier, A. Factors influencing blood concentration of retinol, alpha-tocopherol, vitamin C, and beta-carotene in the French participants of the SU.VI.MAX trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuhouser, M.L.; Rock, C.L.; Eldridge, A.L.; Kristal, A.R.; Patterson, R.E.; Cooper, D.A.; Neumark-Sztainer, D.; Cheskin, J.L.; Thornquist, M.D. Serum Concentrations of Retinol, Alpha-Tocopherol and the Carotenoids Are Influenced by Diet, Race and Obesity in a Sample of Healthy Adolescents. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 2184–2191. [Google Scholar]

- Borel, P.; Desmarchelier, C. Genetic Variations Involved in Vitamin E Status. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waniek, S.; di Giuseppe, R.; Esatbeyoglu, T.; Plachta-Danielzik, S.; Ratjen, I.; Jacobs, G.; Nothlings, U.; Koch, M.; Schlesinger, S.; Rimbach, G.; et al. Vitamin E (alpha- and gamma-Tocopherol) Levels in the Community: Distribution, Clinical and Biochemical Correlates, and Association with Dietary Patterns. Nutrients 2017, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Kelly, F.J.; Salonen, J.T.; Neuzil, J.; Zingg, J.-M.; Azzi, A. The European perspective on vitamin E: Current knowledge and future research. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 703–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.M.; Yu, K.; Weinstein, S.J.; Berndt, S.I.; Hyland, P.L.; Yeager, M.; Chanock, S.; Albanes, D. Genetic variants reflecting higher vitamin e status in men are associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Wei, J.; Citronberg, J.; Hartman, T.; Fedirko, V.; Goodman, M. Relation of Vitamin E and Selenium Exposure to Prostate Cancer Risk by Smoking Status: A Review and Meta-Analysis. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 4983–4996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for vitamin E as α-tocopherol. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilo, E.C.; Costa, P.N.; Gurgel, C.S.S.; Beserra, A.F.d.L.; Almeida, F.N.d.S.; Dimenstein, R. Alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol concentration in vegetable oils. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, K.H.; Kamal-Eldin, A.; Elmadfa, I. Gamma-tocopherol--an underestimated vitamin? Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2004, 48, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traber, M.G. Vitamin E inadequacy in humans: Causes and consequences. Adv. Nutr. 2014, 5, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Christen, S.; Shigenaga, M.K.; Ames, B.N. y-Tocopherol, the major form of vitamin E in the US diet, deserves more attention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.; Kristal, A.R.; Shikany, J.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Chen, C.; Mares-Perlman, J.A.; Masaki, K.H.; Caan, B.J. Correlates of Serum alpha- and gamma-Tocopherol in the Women’s Health Initiative. Ann. Epidemiol. 2001, 11, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.N.; Cho, Y.O. Vitamin E status of 20- to 59-year-old adults living in the Seoul metropolitan area of South Korea. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2015, 9, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Appel, L.J. Supplementation of diets with alpha-tocopherol reduces serum concentrations of gamma- and delta-tocopherol in humans. J. Nutr. 2003, 133, 3137–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, H.; Kono, N. alpha-Tocopherol transfer protein (alpha-TTP). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 176, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgoni, V.L., 3rd; Keast, D.R.; Bailey, R.L.; Dwyer, J. Foods, fortificants, and supplements: Where do Americans get their nutrients? J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1847–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.S.; Luo, P.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, H.; Malafa, M.; Suh, N. Vitamin E and cancer prevention: Studies with different forms of tocopherols and tocotrienols. Mol. Carcinog. 2020, 59, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q. Natural forms of vitamin E: Metabolism, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities and their role in disease prevention and therapy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014, 72, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trujillo, M.; Kharbanda, A.; Corley, C.; Simmons, P.; Allen, A.R. Tocotrienols as an Anti-Breast Cancer Agent. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.D.; Liu, J.; Russell, P.J.; Clements, J.A.; Ling, M.T. Gamma-Tocotrienol Induces Apoptosis in Prostate Cancer Cells by Targeting the Ang-1/Tie-2 Signalling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author (Year) | Location | Study Name | Design | Study Population | Participants | Cases | Age, yrs | Study Duration | Years of Follow Up | Type of Vitamin E Intake | Intake Assessment Method | Vitamin E Cut-Offs | Adjustments for Covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cano-Ibáñez N (2020) [27] | Spain | CAPLIFE | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer at two main university hospitals Controls: Population-based controls | 704 | 402 | Mean: 66.7 Range: 40–80 | 2017–2019 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Adequate intake (8.6 mg/d to 300 mg/d) vs. inadequate intake | Age, smoking habits, physical activity level, educational level, alcohol intake, and first-degree family history of prostate cancer. |

| Lane JA (2017) [28] | UK | - | Nested case-control study | Cases: Men in the Dietary Cohort Consortium Studies diagnosed with prostate cancer Controls: Cohort controls | 5245 | 1717 | Mean: 62.8 Range: 50–60 | 1991–2009 | Mean: 6.6–13.3 years | Dietary | Food diary | Quintiles: 7.1 mg/d, 9.0 mg/d, 11.1 mg/d, 14.1 mg/d | Age, BMI, socioeconomic, smoking, and marital status, diabetes, and energy intake. |

| Sarre S (2016) [29] | Finland | FinsRPC | Prospective cohort study | Men participating in the third round of the FrRSPC without previous diagnosis of prostate cancer | 11,795 | 757 | Median: 66.0 | 2004–2013 | Median: 6.6 years | Supplemental | Self-reported use of supplements | Use vs. no use | Age. |

| Roswall N (2013) [30] | Netherlands | - | Prospective cohort study | Male residents in Denmark | 26,865 | 1571 | Median: 56.0 Range: 50–64 | 1993–2010 | Median: 14.3 years | Dietary, Supplemental, Total | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quartiles for dietary: 7.3 mg/d, 9.5 mg/d, 12.0 mg/d; Supplements: 0 mg/d, 4.4 mg/d, 10 mg/d; Total: 8.6 mg/d, 12.0 mg/d, 17.7 mg/d | Intake of the three other micronutrients as well as dietary intake or supplemental intake of vitamin E. |

| Wang L (2014) [11] | United States | PHS II | RCT | Male physicians aged 50 yrs and above | 13,980 | 1373 | Mean: 64.3 | 1997–2011 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 400 IU vs. no use every other day | Age, PHS cohort and randomised assignment |

| Agalliu I (2011) [31] | Canada | CSDLH | Case-cohort study | Male participants in the CSDLH study recruited from universities in Canada | 2525 | 661 | Mean: 68.4 | 1992–2003 | Mean: 4.3 years | Total | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quintile (median value reported): 6.3 mg/d, 8.3 mg/d, 14.6 mg/d, 264.4 mg/d, 462.0 mg/d | Age, race, BMI, exercise activity, and education. Adjusted for energy intake using residual method. |

| Fleshner N (2011) [13] | Canada | - | RCT | Men with high-grade prostatic interepithelial neoplasia diagnosed within 18 months of random assignment | 303 | 80 | Median: 62.8 | 1999–2004 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 400 IU/d vs. no use | - |

| Klein EA (2011) [12] | United States, Canada, Puerto Rico | SELECT | RCT | Men with prostate- specific antigen concentrations of <4.0 ng/mL | 17,433 | 1149 | Median: 62.5 | 2004–2011 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 400 IU/d vs. no use | - |

| Raimondi S (2010) [32] | Montreal, Canada | - | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer at major teaching hospitals Controls: Population-based controls identified by random-digit dialing | 394 | 197 | Range: 35–84 | 1989–1993 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartiles: 5.9 mg/d; 7.4 mg/d; 9.2 mg/d | Family history of prostate cancer, age group, total energy intake, and calcium intake. |

| Bidoli E (2009) [33] | Italy | - | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer at teaching and general hospitals Controls: Hospital-based controls | 2745 | 1294 | Median: 66 Range: 46–74 | 1992–2002 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Tertiles: 12.3 mg/d, 16.7 mg/d | Age, study center, period of interview, education, body mass index, alcohol intake, smoking habits, family history of prostate cancer and total energy intake. |

| Peters U (2008) [34] | United States | VITAL | Prospective cohort study | Men living in western Washington State covered by the Surveilance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer registry | 35,242 | 830 | Range: 50–76 | 2000–2004 | Not reported | Dietary, Supplemental, Total | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quartiles for dietary: 8.6 mg/d, 12.2 mg/d, 17.1 mg/d. For supplemental: None, 0–30 IU/d, >30–< 400 IU/d, ≥ 400 IU/d. Categories for total: <14.3 mg/d, 14.3–29.3 mg/d, 29.4–98.0 mg/d, ≥98.1 mg/d | Age, family history of prostate cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia, income, multivitamin use, and stratified on PSA screening in the 2 years before baseline (yes/no), energy intake. |

| Zhang YQ (2009) [35] | United States | - | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer at participating hospitals Controls: Hospital-based controls | 4110 | 1706 | Mean: 60.1 Range: 40–79 | 1976–2006 | - | Supplemental | Self-reported use of supplements | Duration of use: 10+ years, 5–9 years, 1–4 years, Never or <1 yr use | Age, years of education, body mass index, current alcohol drinking, current smoking, family history of prostate cancer and use of other vitamin/mineral supplements. |

| Weinstein SJ (2007) [36] | United States | ATBC | Prospective cohort study within trial | Male smoker residents | 29,133 | 1732 | Mean: 57.2 Range: 50–69 | 1985–2004 | Up to 19 years | Dietary, Total | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quintiles for total: 7.06 mg/d. 8.36 mg/d, 10.32 mg/d, 14.72 mg/d; Quintiles for dietary: 6.96 mg/d, 8.13 mg/d, 9.65 mg/d, 13.01 mg/d | Age, trial arm, weight, urban residence, education, intakes of total energy, fat, polyunsaturated fatty acids, vitamin C and lycopene. |

| Wright ME (2007) [37] | United States | NIH-AARP | Prospective cohort study | Men enrolled in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health study | 295,344 | 10,241 | Range: 50–71 | 1995–2000 | Up to 5 years | Dietary, Supplemental | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quintile medians for dietary: 4.8 mg/d, 6.5 mg/d, 7.0 mg/d, 8.0 mg/d, 10.0 mg/d; For supplement: 0 IU/d, >0–99 IU/d, 100–199 IU.d, 200–399 IU/d, 400–799 IU/d. ≥800 IU/d | Age, race, smoking status, education, personal history of diabetes, family history of prostate cancer, body mass index, and dietary intakes of red meat, a-linolenic acid, vitamin C, B carotene intake. Dietary tocopherols were adjusted for energy intake using theresidual method. |

| Kirsh VA (2006) [38] | United States | PLCO Cancer Screening Trial | Prospective cohort study | Men in the screening arm of the PLCO trial | 29,361 | 1338 | Mean: 63.3 Range: 55–74 | 1993–2001 | Mean: 4.2 years | Dietary, Supplemental | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quintiles medians for dietary: 8.6 mg/d, 10.2 mg/d, 11.3 mg/d, 12.6 mg/d, 15.8 mg/d; For supplements: 0 IU/d, >0–30 IU/d, >30–400 IU/d, | Age, total energy, race, study center, family history of prostate cancer, BMI, smoking status, physical activity, total fat intake, red meat intake, history of diabetes, aspirin use, number of screening examinations during follow-up period. |

| Stram DO (2006) [39] | United States | MEC | Prospective cohort study | Men from a large population-based multiethnic cohort | 82,486 | 3922 | Range: 45–75 | 1993–2001 | Up to 7 years | Dietary, Supplemental | FFQ | Quintiles for dietary: 3.9 mg/1000 kcal, 4.5 mg/1000 kcal, 5.1 mg/1000 kcal, 6.0 mg/1000 kcal; For supplements: 0–<33.75 mg/d, ≥33.75 mg/d | Age, ethnicity, BMI, education and family history of prostate cancer. Intake of all foods and nutrients were analysed as nutrient densities. |

| Lonn E (2005) [14] | Canada, United States, Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and 14 Western European countries | HOPE and HOPE-TOO | RCT | Male patients at high risk for cardiovascular events | 6996 | 235 | Mean: 66.0 | 1993–1999; 1999–2003 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 400 IU/d vs. 0 IU.d | - |

| McCann SE (2005) [40] | United States | WNYDS | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer from major hospitals Controls: Population-based controls | 971 | 433 | Mean: 69.5 | 1986–1991 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartile range: <7 mg/d. 7–9 mg/d, 9–11 mg/d, >11 mg/d | Age, education, BMI, cigarette smoking status, total energy, vegetable intake. |

| Meyer F (2005) [10] | Canada | SU.VI.MAX | RCT | Healthy male volunteers | 5034 | 103 | Mean: 51.3 Range: 45–60 | 1994–2002 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 30 mg/day vs. no use | - |

| Hodge M (2004) [41] | Australia | - | Case-control study | Cases: Australian male residents with prostate cancer Controls: Population-based controls | 1763 | 858 | Range: < 70 | 1994–1997 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quintile range: <6.9 mg/d, 6.9–8.0 mg/d, 8.1–9.0 mg/d. 9.1–10.3 mg/d, ≥10.4 mg/d | State, age group, year, country of birth, socio-economic group, family history of prostate cancer. Nutrient adjusted for energy intake by residual method. |

| Rodriguez C (2004) [42] | United States | CPS-II | Prospective cohort study | Men selected from the CPS-II Nutrition Cohort | 72,704 | 4281 | Range: 50–74 | 1992–1999 | Not reported | Supplemental | FFQ | None, 1–31 IU/d, 32–≤400 IU/d, ≥400 IU/d | Age, race, smoking status, BMI, education, energy adjusted calcium, total fat, lycopene intake, total calorie intake, family history of prostate cancer, and PSA history. |

| Schuurman (2002) [43] | Netherlands | NLCS | Case-cohort study | Men from the study population in NLCS | 2167 | 642 | Mean: 62.1 Range: 55–69 | 1986–1992 | Up to 6.3 years | Dietary, Supplemental | FFQ, self-reported use of supplements | Quintile medians: 7.1 mg/d, 10.4 mg/d, 13.5 mg/d, 17.3 mg/d, 23.6 mg/d | Age, family history of prostate cancer, socioeconomic status, and alcohol from white or fortified wine. |

| Ramon JM (2000) [44] | Spain | - | Case-control study | Case: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer in hospital records Controls: Hospital and population-based controls | 651 | 217 | - | 1994–1998 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartile medians: 6.1 mg/d, 7.6 mg/d, 9.9 mg/d, 12.8 mg/d | Age, residence, calories, family history and BMI. |

| Chan JM (2000) [45] | United States | HPFS | Prospective cohort study | Male health professionals | 47,780 | 1896 | Mean: 54.6 Range: 40–75 | 1986–1996 | Not reported | Supplemental | FFQ and self-reported use of supplements | 0 IU/d, 0.1–15.0 IU/d, 15.1–99.9 IU/d, ≥100 IU/d | Age, period, family history of prostate cancer, vasectomy, smoking, quintiles of BMI, BMI at age 21, physical activity, quintiles of total calories, calcium, lycopene, fructose, and fat intake per day. |

| Deneo-Pellegrini H (1999) [46] | Uruguay | - | Case-control study | Case: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer admittted to major hospitals Controls: Hospital-based controls | 408 | 175 | Range: 40–89 | 1994–1997 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartile ranges: ≤5.0 mg/d, 5.1–6.0 mg/d, 6.1–7.8 mg/, ≥7.9 mg/d | Age, residence, urban/rural, family history of prostate cancer, BMI, total energy intake. |

| Jain MG (1999) [47] | Canada | - | Case-control study | Cases: Men recently diagnosed with prostate cancer identified by hospital admission offices or cancer registries Controls: Population-based controls | 1253 | 617 | Mean: 69.9 | 1989–1993 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartile ranges: <17.17 mg/d, 17.17–25.30 mg/d, 25.31 mg/d, 37.25 mg/d, ≥37.25 mg/d | Age, log total energy intake, vasectomy, marital status, ever smoke study area, BMI, education, ever-used multivitamin supplements, area of study, log-amounts for grains, fruits, vegetables, total plants, total carotenoids, folic acid, dietary fibre, conjugated linoleic acid, vitamin E, vitamin C, retinol, total fat, and linolenic acid. |

| Kristal AR (1999) [48] | United States | - | Case-control study | Men diagnosed with prostate cancer, identified from the Seattle-Puget Sound SEER cancer registry Controls: Population-based controls | 1363 | 697 | Range: 40–64 | 1993–1996 | - | Supplemental | Self-reported use of supplements | Frequency of use: 0/week, <1/week, 1–6/week, ≥7/week | Age, race, education, energy, family history of prostate cancer, body mass index, number of PSA tests in previous 5 years, dietary fat intake. |

| Heinonen OP (1998) [9] | Finland | ATBC | RCT | Male smokers residents | 29,133 | 246 | Mean 57.1 Range: 50–69 | 1985–1993 | - | Supplemental | Intervention | 50 mg/d vs. no use | - |

| Key TJA (1997) [49] | UK | - | Case-control study | Cases: Men diagnosed with prostate cancer based on hospital registry records Controls: Patients of the general pracitioners for cases | 656 | 328 | Mean: 68.1 | 1990–1994 | - | Dietary, Total | FFQ | Tertile ranges for dietary: <9.59 mg/d, 9.59–16.33 mg/d, ≥16.34 mg/d; Tertile ranges for total: <9.94 mg/d, 9.94–17.87 mg/d, ≥17.88 mg/d | Energy. |

| Vlajinac HD (1997) [50] | Serbia | - | Case-control study | Cases: Patients diagnosed with prostate cancer Controls: Hospital-based controls | 303 | 101 | Mean: 71.2 | 1990–1994 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Tertiles; no cut-off values reported | Energy, protein, fat-total, saturated fatty acids, carbohydrate, sugar, fibre, retinol, retinol equivalent, folic acid, vitamin B12, sodium, potassium, calcium, phosphorous magnesium and iron. |

| Andersson SO (1996) [51] | Sweden | - | Case-control study | Cases: Male residents in Sweden diagnosed with prostate cancer, identified through hospital records Controls: Population-based controls | 1062 | 526 | Mean: 70.6 | 1989–1994 | - | Dietary | FFQ | Quartiles: 4.5 mg/d, 5.7 mg/d, 7.3 mg/d | Age and energy adjusted, based on nutrient residuals and energy in quartiles. |

| Shibata A (1992) [52] | United States | - | Prospective cohort study | Male residents of a retirement community | 4252 | 207 | Mean: 74.9 | 1981–1989 | Up to 8 years | Supplemental | Self-reported use of supplements | Use vs. no use | Age and smoking habits. |

| Type of Vitamin E Intake | No. of Studies | Sample Size | RR (95% CI) | I2 Value (%) | p Value for Subgroup Differences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary intake | |||||

| Study design | |||||

| Case-control studies | 13 | 18,322 | 0.93 (0.84–1.02) | 28.34 | 0.289 |

| Cohort studies | 6 | 498,431 | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 12.48 | |

| Sample size | |||||

| <1000 | 7 | 4087 | 0.77 (0.54–1.10) | 72.12 | 0.605 |

| >1000 | 12 | 512,666 | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 5.22 | |

| Geographical region | |||||

| North America | 8 | 474,184 | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 12.40 | 0.036 |

| Europe | 9 | 40,398 | 0.92 (0.84–1.01) | 0.02 | |

| Vitamin E intakea | |||||

| ≥15 mg/day | 10 | 189,841 133,729 | 0.94 (0.86–1.02) | 0.00 | |

| Supplemental intake of vitamin E | |||||

| Study type | |||||

| Observational | 12 | 613,469 | 0.99 (0.95–1.04) | 0.04 | 0.133 |

| Interventional | 6 | 72,879 | 0.96 (0.82–1.13) | 72.90 | |

| Study type | |||||

| Case-control studies | 3 | 7640 | 0.88 (0.63–1.22) | 51.49 | 0.451 |

| Cohort studies | 9 | 605,829 | 1.00 (0.95–1.04) | 0.00 | |

| Sample size | |||||

| <20,000 | 10 | 67,433 | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 34.36 | 0.094 |

| >20,000 | 8 | 618,915 | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 11.20 | |

| Geographical region | |||||

| North America | 13 | 609,392 | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | 18.76 | 0.020 |

| Europe | 4 | 69,960 | 0.81 (0.69–0.97) | 33.56 | |

| Dose of supplements used | |||||

| ≥400 IU | 7 | 457,383 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 40.67 | |

| RCTs using dose <400 IU/day | 3 | 48,147 | 0.85 (0.67–1.09) | 69.43 | 0.541 |

| RCTs using dose ≥400 IU/day | 3 | 24,732 | 1.11 (0.97–1.27) | 16.82 | |

| Study population | |||||

| RCTs participants without underlying conditions | 4 | 65,580 | 0.93 (0.74–1.18) | 86.18 | 0.712 |

| RCTs participants with underlying conditions | 2 | 7299 | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 0.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loh, W.Q.; Youn, J.; Seow, W.J. Vitamin E Intake and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15010014

Loh WQ, Youn J, Seow WJ. Vitamin E Intake and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2023; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoh, Wei Qi, Jiyoung Youn, and Wei Jie Seow. 2023. "Vitamin E Intake and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15010014

APA StyleLoh, W. Q., Youn, J., & Seow, W. J. (2023). Vitamin E Intake and Risk of Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15010014