Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

Urban Indigenous Food Environments

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Community Context

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks and Study Design

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

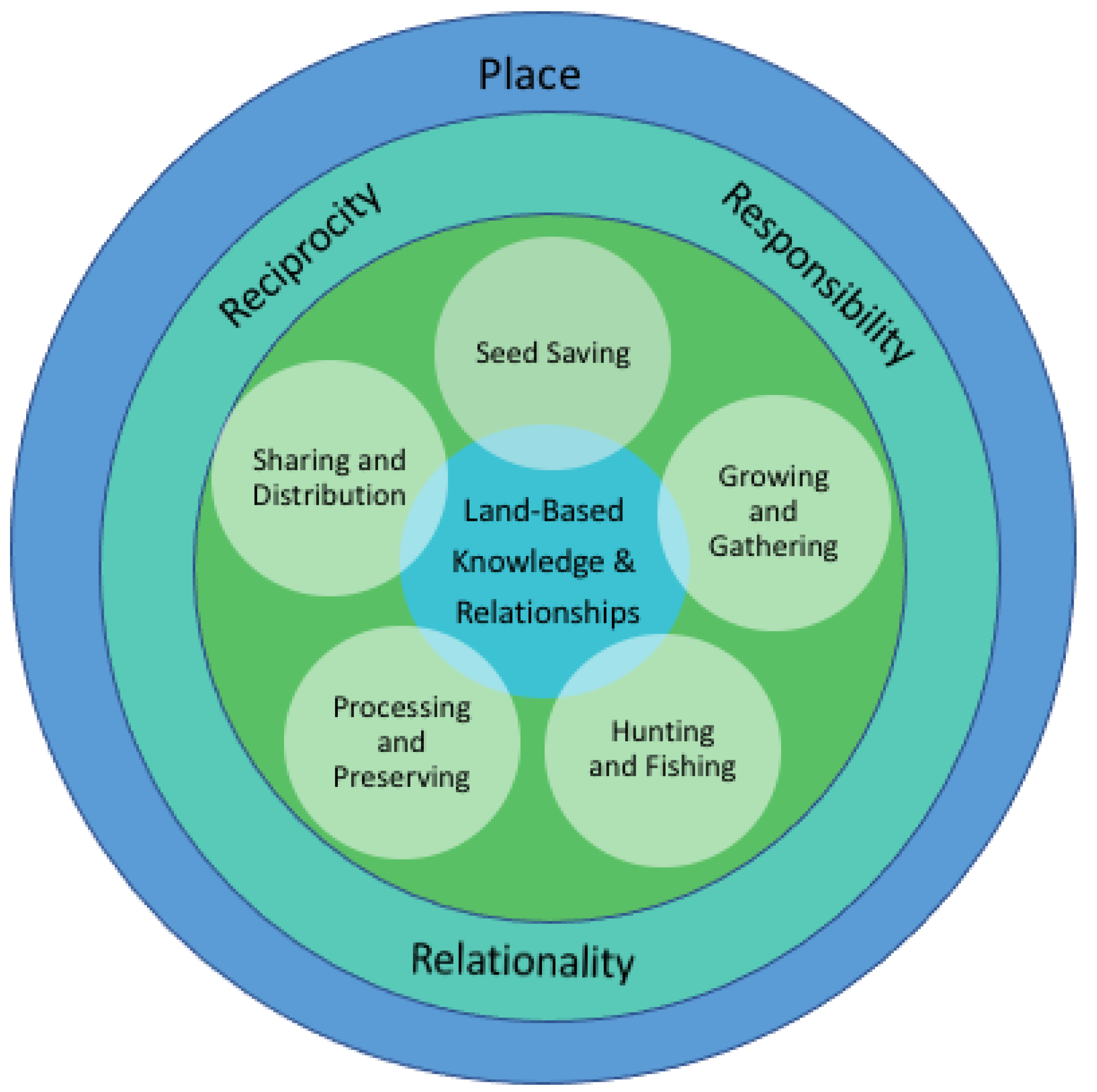

3.1. Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity

Creation ensured that all created holds a part of Creation/Spirit. It might be said that this “holding of Spirit” was the first commitment/responsibility/treaty between Creator and that Created…This responsibility honours the reciprocity, how we give back to Creation’s Garden, Mother Earth.

It’s understanding I have much more than I need, and I have the capacity to share with others, so I need to do that in order to satisfy my responsibility to the Land and others around me…I see it as connecting to our sense of responsibility that is linked to reciprocity. Inherently, we have a responsibility to the Land and that is to first and foremost harvest in a respectful way. But then I think that responsibility extends to the way we share the food.

As Creator knows me, I act on my original instructions. I walk this red path in the physical realm, to observe, listen and learn from seeds, plants and all those other Relations, our Kin. We are all interconnected. One of the ways I honour with humility and gratitude, this Earth our Mother and All Ancestors, is by being a seed keeper of a number of plants/roots/barks/flowers/seeds specific to my Clan. I do this in Ceremony, with Community to produce, gather, prepare, feast and for healing. I do this for now and for the generations of All Our Relations whose faces we have yet to see.

3.2. Land- and Food-Based Practices

It starts with seeds, right? Every person having seeds in their hand and those seeds growing food for themselves, their families, their community, but also being able to put some aside for seeds again. [There’s] that cycle of provision; giving and preparation. Provision for your family, for your neighbour, giving of seeds back to community for others who don’t have what they need yet.

Planting and saving seeds and planting again are these beautiful ways of really being able to witness the unfolding aspect of life. So, I was always really intrigued by that and really excited to be able to use my hands to co-create with, in relationship with these plants, but also in relationship with the Creator and what the Creator had intended for us to be, right? Cause these relationship beings, when we receive from those plants that we are also, that our responsibility is to save those seeds and keep that plant alive.

Back in Saskatchewan when I was in an urban setting, I had a little bit more access to [wild meat] because I had a network of people. And so, it was still relatively easy to get or to trade for wild meat… but when I got out here, I didn’t have that network and I still don’t really have strong enough ties [here] to access wild meat.

I think that our work has not only been able to nourish bodies in terms of nutrients but also souls and spirits of people. Not everybody that we’ve been giving boxes to are in dire, dire need of food physically. But they may be kind of spiritually deprived because they are stuck at home doing Zoom calls by themselves.

We kind of operate in a circular way, like we’re all equal… and that’s translated to how we share our food… And I think that there’s something refreshing but also beautiful about it because in each exchange between people throughout the process of food growing and food giving there’s a reciprocal thing going on that builds relationship…because the entire process has to do with community really, and relationship with others. Not only do we rely on volunteers, and the combined collective work of all of us, but we also rely on the Earth and the Land to teach us and help us through the process.

4. Discussion

Recommendations for Future Research

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morrison, D. Indigenous food sovereignty: A model for social learning. In Food Sovereignty in Canada: Creating Just and Sustainable Food Systems; Desmarais, A., Wiebe, N., Eds.; Fernwood Publishing: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2011; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Settee, P.; Shukla, S. Introduction. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, D. Reflections and realities: Expression of food sovereignty in the fourth world. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Delormier, T.; Horn-Miller, K.; McComber, A.M.; Marquis, K. Reclaiming food security in the Mohawk community of Kahnawà:ke through Haudenosaunee responsibilities. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigle, M. Tracing the terrain of Indigenous food sovereignties. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 46, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Receveur, O. Dietary change and traditional food systems of Indigenous Peoples. Annu. Rev. 1996, 16, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willows, N.D. Determinants of health eating in Aboriginal Peoples in Canada: The current state of knowledge and research gaps. Can. J. Public Health 2005, 96, S32–S36. [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin, E.M.; Hayes, M. A collection of voices: Land-based leadership, community wellness and food knowledge revitalization of the Tsartlip First Nation garden Project. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, T. Our Hands at Work: Indigenous Food Sovereignty in Western Canada. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.G.; Linklater, R.; Thompson, S.; Dipple, J.; Ithinto Mechisowin Committee. A recipe for change: Reclamation of Indigenous food sovereignty in O-Pipon-Na-Piwin Cree Nation for decolonization, resource sharing, and cultural restoration. Globalizations 2015, 12, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidro, J.; Adekunle, B.; Peters, E.; Martens, T. Beyond food security: Understanding access to cultural food for urban Indigenous people in Winnipeg as Indigenous food sovereignty. Can. J. Urban Res. 2015, 24, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Big-Canoe, K.; Richmond, C.A. Anishinaabe youth perceptions about community health: Towards environmental repossession. Health Place 2014, 26, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michnik, K.; Thompson, S.; Beardy, B. Moving your body, soul and heart to share and harvest food. Can. Food Studies. 2021, 8, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delormier, T.; Marquis, K. Building Healthy Community Relationships Through Food Security and Food Sovereignty. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, K.; Lickers Xavier, A.; Tait-Neufeld, H. Healthy Roots: Building capacity through shared stories rooted in Haudenosaunee knowledge to promote Indigenous foodways and well-being. Can. Food Stud. 2018, 5, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundel, E.; Chapman, G.E. A decolonizing approach to health promotion in Canada: The case of the Urban Aboriginal Community Kitchen Garden Project. Health Promot. Int. 2010, 25, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peach, L.; Richmond, C.A.; Brunette-Debassige, C. “You can’t just take a piece of Land from the university and build a garden on it”: Exploring Indigenizing space and place in a settler Canadian university context. Geoforum 2020, 114, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, H.; Richmond, C. Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre. Impacts of place and social spaces on traditional food systems in Southwestern Ontario. Int. J. Indig. Health 2017, 12, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, H.; Richmond, C. Exploring First Nation Elder women’s relationships with food from social, ecological, and historical perspectives. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: An Assessment of the State of Knowledge. Available online: https://cca-reports.ca/reports/aboriginal-food-security-in-northern-canada-an-assessment-of-the-state-of-knowledge/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Wendimu, M.; Desmarais, A.; Martens, T. Access and affordability of “healthy” foods in northern Manitoba? The need for Indigenous food sovereignty. Can. Food Stud. 2018, 5, 44–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neufeld, H.T. Socio-Historical Influences and Impacts on Indigenous Food Systems in Southwestern Ontario: The Experiences of Elder Women living on-and off-reserve. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, C.; Steckley, M.; Neufeld, H.; Kerr, R.B.; Wilson, K.; Dokis, B. First Nations food environments: Exploring the role of place, income, and social connection. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, K.; Pratley, E.; Burnett, K. Eating in the city: A review of the literature on food urban spaces. Societies 2016, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, C.; Kerr, R.B.; Neufeld, H.; Steckley, M.; Wilson, K.; Dokis, B. Supporting food security for Indigenous families through the restoration of Indigenous foodways. Can. Geogr. 2021, 65, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, B.; Jayatilaka, D.; Brown, C.; Varley, L.; Corbett, K. “We are not being heard”: Aboriginal perspectives on traditional foods access and food security. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouri, L.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Thomson, T.; Wood, M. Food justice in the innter city: Reflection from a program of public health nutrition research in Saskatchewan. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- 2016 Census Topic: Aboriginal Peoples. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/rt-td/ap-pa-eng.cfm (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- The Urban Indigenous Action Plan. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/uiap_full_report_en.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Urban Aboriginal Peoples Study. Available online: https://www.uaps.ca/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/UAPS-Main-Report_Dec.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- COVID-19 Did not Cause Food Insecurity in Indigenous Communities but it Will Make it Worse. Available online: https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/04/29/covid19-food-insecurity/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Seed Sowing: Indigenous Relationship-Building as Processes of Environmental Action. Available online: https://climatechoices.ca/publications/seed-sowing-indigenous-relationship-building/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Ojibiikaan. Available online: https://ojibiikaan.com/about-us/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Nelson, S.E.; Wilson, K. Indigenous health organizations, Indigenous community resurgence, and the reclamation of place in urban areas. Can. Geogr. 2021, 65, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltenburg, E. “Where Creator has my Feet, There I Will Be Responsible”: Impacts of Place on Urban Indigenous Food Sovereignty Initiatives across Grand River Territory. Master’s Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, GO, Canada, April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Our Watershed, Grand River Conservation Authority. Available online: https://www.grandriver.ca/en/our-watershed/Our-Watershed (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Population Estimates, July 1, by Census Metropolitan Area and Census Agglomeration, 2016 Boundaries. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710013501 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Indigenous Engagement, Wellington Waterloo Local Health Integration Network. Available online: http://www.waterloowellingtonlhin.on.ca/communityengagement/IndigenousEngagement.aspx#:~:text=The%20Waterloo%20Wellington%20Local%20Health,health%20planning%20and%20decision%20making.&text=The%20WWLHIN%20is%20home%20to,480%20Inuit%20and%204585%20Metis (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Census Profile, 2016, Census. Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=3523008&Geo2=CD&Code2=3523&Data=Count&SearchText=guelph&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=All&TABID=1 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Wisahkotewinowak. Available online: https://www.wisahk.ca/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Indigenous Food Sovereignty Collective Waterloo Region. Available online: https://indigenousfoodsovereigntycollectivewaterlooregion.community/#:~:text=We%20help%20to%20facilitate%20meals,seeds%20for%20the%20next%20generations (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Ceremonial Fire Grounds. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/stpauls/waterloo-indigenous-student-centre/ceremonial-fire-grounds-0 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Absolon, K.; Willett, C. Putting ourselves forward: Location in Aboriginal research. In Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-Oppressive Approaches; Strega, S., Brown, L., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005; pp. 97–126. [Google Scholar]

- Learning across Indigenous and Western Knowledge Systems and Intersectionality: Reconciling Social Science Research Approaches. Available online: https://www.criaw-icref.ca/images/userfiles/files/Learning%20Across%20Indigenous%20and%20Western%20KnowledgesFINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Dawson, A.; Toombs, E.; Mushquash, C. Indigenous research methods: A systematic review. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2017, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, S. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods; Fernwood Publishing: Black Point, NS, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K.; Cidro, J. Decades of doing: Indigenous women academics reflect on the practices of Community-Based Health Research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2019, 14, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castleden, H.; Morgan, V.S.; Lamb, C. “I spent the first-year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous Peoples. Can. Geogr. 2012, 56, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Nations Principles of OCAP. Available online: https://fnigc.ca/ocap-training/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Schnarch, B. Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) or Self-Determination Applied to Research. J. Aborig. Health 2004, 1, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- USAI Research Framework, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres [OFIFC]. Available online: https://ofifc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/USAI-Research-Framework-Second-Edition.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Planning and designing qualitative research. In Successful Qualitative Research: A practical Guide for Beginners; Carmichael, M., Clogan, A., Eds.; Sage publications: London, UK, 2013; pp. 42–74. [Google Scholar]

- Lavallée, L.F. Practical application of an Indigenous research framework and two qualitative Indigenous research methods: Sharing circles and Anishnaabe symbol-based reflection. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Morgan, V.S.; Neimanis, A. Researchers’ perspectives on collective/community co-authorship in community-based participator Indigenous research. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2010, 5, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, E.M. Conceptualizing food security for Aboriginal people in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2008, 99, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First Nations Food, Nutrition, & Environment Study. Available online: https://www.fnfnes.ca/docs/CRA/FNFNES_draft_technical_report_Nov_2__2019.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Timler, K.; Brown, H. Fostering Food Sovereignty and Social Citizenship for Indigenous People in British Columbia. BC Stud. 2019, 202, 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Timler, K.; Sandy, D.W. Gardening in ashes: The possibilities and limitations of gardening to support indigenous health and well-being in the context of wildfires and colonialism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.; Slater, J. Honouring the grandmothers through (re)membering, (re)learning, and (re)vitilizing Metis traditional foods and protocols. Can. Food Stud. 2019, 6, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L. “Food will be what brings the people together”: Constructing counter-narratives from the perspective of Indigenous foodways. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, R.; Batal, M.; Johnson-Down, L.; Johnson, S.; Louie, C.; Terbasket, E.; Terbasket, P.; Wright, H.; Willows, N. An Indigenous food sovereignty initiative is positively associated with well-being and cultural connectedness in a survey of Syilx Okanagan adults in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coté, C. “Indigenizing” food sovereignty. Revitalizing Indigenous food practices and ecological knowledges in Canada and the United States. Humanities 2016, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska-Mainville, A. Aki Miijim (Land Food) and the Sovereignty of the Asatiwispe Anishinaabeg Boreal Forest Food System. In Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations; Settee, P., Shukla, S., Eds.; Canadian Scholars Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 57–81. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, T.; Cidro, J.; Hart, M.A.; McLachlan, S. Understanding Indigenous food sovereignty through an Indigenous research paradigm. J. Indig. Soc. Dev. 2016, 5, 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Koberinski, J.; Vivero-Pol, J.L.; LeBlanc, J. Reframing food as a commons in Canada: Learning from customary and contemporary indigenous food initiatives. In Critical Food Guidance; Sumner, J., Desjardins, E., Eds.; McGill University Press: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Growing Resilience and Equity: A food Policy Action Plan in the Context of COVID-19. Available online: https://foodsecurecanada.org/sites/foodsecurecanada.org/files/fsc_-_growing_resilience_equity_10_june_2020.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Levkoe, C.; Ray, L.; Mclaughlin, J. The Indigenous food circle: Reconciliation and resurgence through food in Northwestern Ontario. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maracle, S.; Bergier, A.; Anderson, K.; Neepin, R. “The work of a leader is to carry the bones of the people”: Exploring female-led articulation of Indigenous knowledge in an urban setting. AlterNative 2020, 16, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name or Pseudonym | Location | Indigenous Identity | Connection to IFS Initiative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dave | Kitchener | Métis | Wisahkotewinowak |

| Garrison | Kitchener | First Nations | Wisahkotewinowak |

| Sarina | Kitchener | Métis | Wisahkotewinowak |

| Beth | Cambridge | First Nations | Waterloo Region Indigenous Food Sovereignty Collective |

| Rachel | Kitchener | First Nations | Waterloo Region Indigenous Food Sovereignty Collective |

| Lori | Waterloo | Cree-Métis | Waterloo Indigenous Student Centre-Shatitsirótha |

| Nookomis | Guelph | First Nations | North End Harvest Market |

| Beans | Corn | Squash | Medicines | Berries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cherokee Trail of Tears Succotash Red Runner | Lenape Blue Mohawk White | Arikara Lenape Gete Okosomin | Sweetgrass Tobacco Mullein Pearly Everlasting Mountain Sage Prairie Sage | Strawberries Saskatoon |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miltenburg, E.; Neufeld, H.T.; Anderson, K. Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091737

Miltenburg E, Neufeld HT, Anderson K. Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments. Nutrients. 2022; 14(9):1737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091737

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiltenburg, Elisabeth, Hannah Tait Neufeld, and Kim Anderson. 2022. "Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments" Nutrients 14, no. 9: 1737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091737

APA StyleMiltenburg, E., Neufeld, H. T., & Anderson, K. (2022). Relationality, Responsibility and Reciprocity: Cultivating Indigenous Food Sovereignty within Urban Environments. Nutrients, 14(9), 1737. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14091737