Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

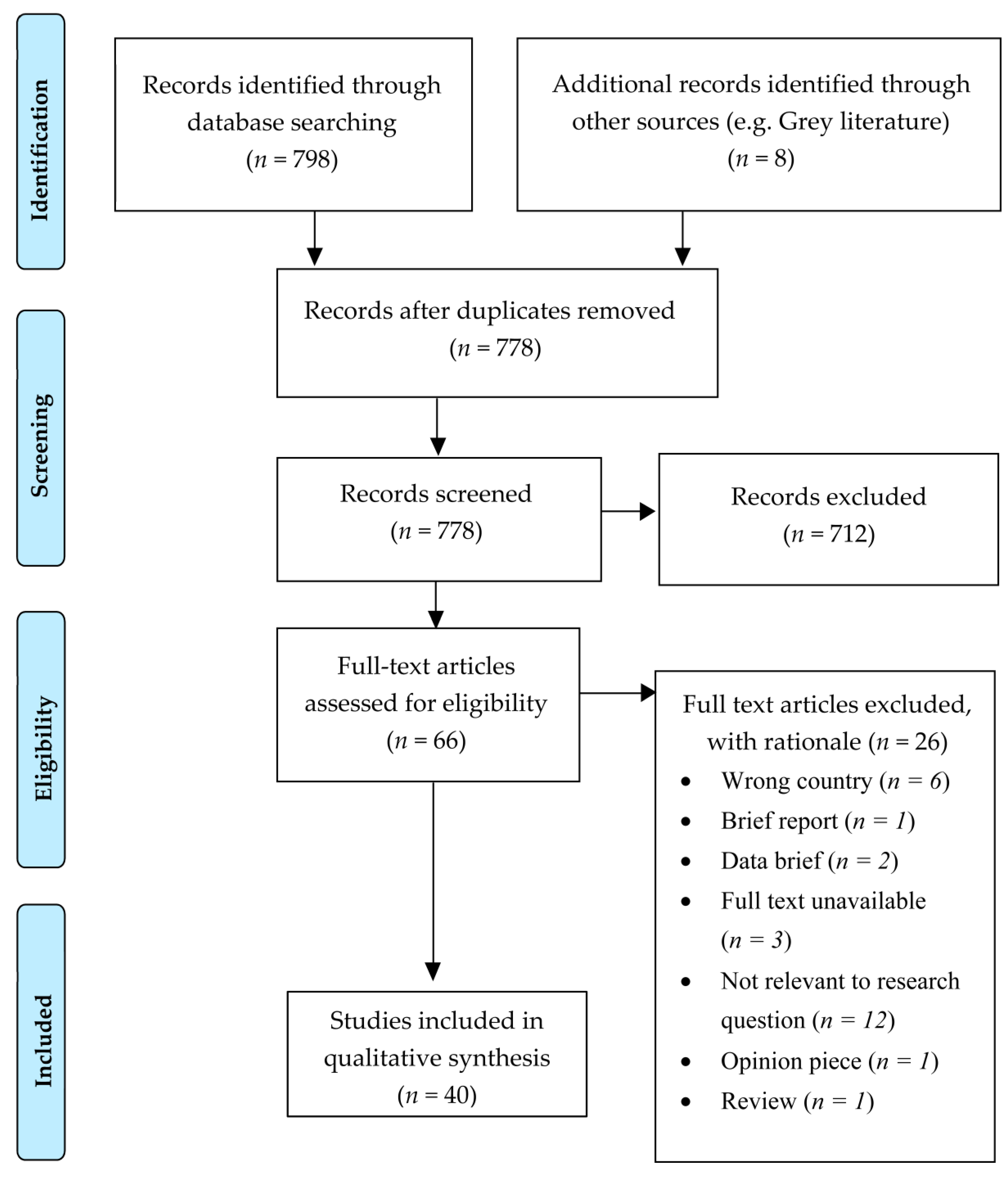

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Countries

3.3. Study Design

3.4. Observations

3.5. Interventions

3.5.1. Educational

3.5.2. Labelling

3.5.3. Financial

3.5.4. Choice Architecture

3.5.5. Implementing Standards and Guidelines

3.5.6. Multi-Component Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Scopus Search Criteria

Appendix A.2. Embase, Medline and APA PsycInfo Controlled Vocabulary Search

Appendix B

| Citation, Country | Study Design, Duration | Aim of Study | Participants/ Hospitals | Intervention | Outcome Measures | Results | Risk of Bias Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abel et al. (2015) [16], USA | RCT, 4 weeks | Assess knowledge of government reference values among the public and assess the impact of email/text interventions on calorie reference value knowledge. | n = 246 hospital employees and students | Assess knowledge of reference values, deliver weekly text or email prompts regarding calorie intake, then administer a follow-up test to assess impact of intervention. | Knowledge of government reference values and impact of intervention on self-reported calorie consumption. | At baseline, 42.2% of participants knew the 2000 calorie reference value. Following text intervention, participants 2x as likely to know the reference value as the control group (p = 0.047, odds ratio = 2.2, 95% confidence interval [1.01, 4.73]). No significant difference between text and email conditions. 52% of participants would use the information when making future food decisions. 32% stated that the intervention led to lower calorie intake than if the information was available on menus and posters—no statistically significant change in self-reported calorie consumption or portion size. | + |

| Allan and Powell (2020) [31], UK | RCT, 6 months | Reduce purchase of unhealthy single-serve snacks. | n = 30 hospital food outlets | Implement tailored point-of-purchase signs displaying calorific values of the items for sale. | Average energy, fat and sugar content of purchases per day, average cost of each purchase and total number of purchases per day. | Purchases significantly lower in calories (95% CI: −0.83, −2.85, p < 0.001), sugar content and cost (95% CI: −0.46, −1.32, p < 0.001) post-intervention compared to pre-intervention. This was also true for calories (p = 0.049) and cost (p = 0.03) comparing intervention to the control site. No significant differences in fat content (p = 0.07), sugar content (p = 0.48) or number of purchases (p = 0.64) between intervention and control sites. | + |

| Bak et al. (2020) [17], UK | Observational, 2 h (per focus group) | Investigate beliefs of student nurses about causes of nurses’ health-related behaviours, plus strategies to improve these behaviours. | n = 20 undergraduate nursing students | Ask student nurses about underlying factors for health-related behaviours, reasoning behind these behaviours and identifying stakeholders responsible for implementing solutions. | Student views regarding the underlying causes of health-related behaviours among nurses and how these could be improved. | Four key causes of negative health-related behaviours identified: Knowledge, shift-work, culture and stress. Several students reported snacking was common during night-shifts and few healthy food options were available within hospitals. They also suggested that high stress triggers a desire to eat “comfort foods”, which are often high in fat. The idea of subsidising healthy food options for staff was raised as a possible strategy to improve food-related behaviours. | ∅ |

| Block et al. (2010) [53], USA | RCT, 6 weeks | Assess the impact of increasing the prices of sugar-sweetened soft drinks and educational interventions on beverage sales. | n = 1 hospital food outlet and n = 154 survey respondents | 5 phase intervention involving 35% price increase on soft drinks, an educational campaign (posters and flyers) and combined price increase and educational campaign. | Number and category of drinks purchased per day and total number of beverage sales. | Sales of regular, sugar-sweetened soft drinks significantly decreased during intervention, while sales of diet soft drinks increased. Regular soft drink sales decreased by 26% during price increase (95% CI = 39.0, 14.0) and 36% (95% CI = 49.0, 23.0)in the combination phase (education and price increase). Education alone did not significantly impact sales of regular soft drinks, despite a 9% sales increase (95% CI = −4.0, 22.0). 44% of survey participants noticed an intervention, with 82% being aware of the educational phase and 18% being aware of the price increase. | + |

| Derrick et al. (2015) [32], USA | Observational, short duration | Describe nutrition environments in hospitals that participate in the One Health Care System and investigate the impact of the LiVe Well Plate initiative. | n = 21 hospital food outlets | Assess food environment using the Hospital Nutrition Environment Scan, including signage, menu information and pricing strategies. Implement the LiVe Well Plate in low-scoring hospitals based on menu factors. | Nutrition composite scores of cafeterias and nutrition scores based on barriers and facilitators, grab-and-go items, menu offering and point-of-purchase options. | Mean nutrition composite score was 49.2 ± 8.1 in hospitals which adhered to the LiVe Well Plate and 29.7 ± 11.3 in hospitals which did not. Those adhering to the initiative had significantly higher scores for facilitators and barriers (p < 0.001) and point-of-purchase options (p = 0.013) than the other group and two locations promoted healthy food choices via pricing. No significant differences between groups for grab-and-go (p = 0.178) or menu options (p = 0.172). | ∅ |

| Elbel et al. (2013) [33], USA | RCT, 6 months | Investigate the impact of taxation and food labelling interventions on healthy produce purchases. | n = 1 hospital food outlet | 5 phase intervention involving product labelling, a 30% taxation on less healthy items, a combined intervention and a combined intervention with taxation rationale stated on products. | Number and nutritional quality of purchases. | At baseline, 47.2% of purchases were healthy (95% CI = 43%, 52%). This rose to 54% in the labelling condition (95% CI = 49%, 58%) and 59% under the taxation conditions (95% CI = 56%, 61%; not shown). Taxation conditions did not significantly differ (p on Wald test = 0.82); all increased probability of healthy purchase by 10–12% (p < 0.001). Taxation associated with fewer unhealthy food choices (AME = −9.41%, 95% CI = −13.80%, −5.03%, p < 0.001) and more healthy beverage purchases (AME = 5.87%, 95% CI = 2.36%, 9.38%, p = 0.001). Unclear if taxation had a greater impact than labelling. | ∅ |

| Goldstein et al. (2014) [18], USA | Observational, short duration | Investigate physician perspectives on hospital support available to promote healthy hospital environments. | n = 1485 physicians | Physicians were asked to rate their place of work based on support offered for achievement and maintenance of a healthy food environment and physical activity. | Physician rating of hospital support | Health-promoting environments were mostly rated ‘good’, with 70% of respondents suggesting that nutrition environments were supportive. Responses varied according to socioeconomic status of the average patient (higher ratings were given by physicians seeing lower middle class [OR: 1.74 (1.27–2.39)], upper middle class [2.23 (1.61–3.09)] to affluent patients [2.91 (95% CI: 1.49–5.66)] compared to physicians seeing very poor to lower/middle-class patients). 40% of respondents stated that their facilities supported healthy nutrition. | + |

| Griffiths et al. (2020) [34], UK | RCT, 24 weeks | Assess health benefits and cost-effectiveness of replacing regular snacks with healthy options. | n = 2 hospital food outlets | Vending machines in 2 locations were exposed to alternating “healthy” or “unhealthy” conditions, with all products costing the same amount. | Sales volume, profit and calories sold. Compensatory behaviours (sales data from nearby shop), number of items purchased by each customer and time taken to complete each purchase | The healthy condition was associated with a 61% decrease in calories purchased, which was significant (SE = 579.23; t = −3.868; p < 0.0001) and a GBP 1116 decrease in profits. There was no significant impact on number of sales and no significant association between calorie content and sales volume. No significant difference in sales from a local shop (SE = 0.848; t = 0.249; p = 0.81), suggesting no compensatory behaviours. No significant difference in the likelihood of single versus multiple item purchases between conditions (χ2 (1) = 2.20, p = 0.14). | ∅ |

| Grivois-Shah et al. (2018) [43], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 6 months | Assess the impact of increasing the proportion of healthy options in vending machines on calorie, fat, sugar and salt purchase, plus sales revenue. | n = 23 hospitals | Proportion of healthy “Right Choice” items in vending machines was increased from 20% to 80%. | Percentage of healthy options vended and total number of items vended. Mean revenue, calorific value, fat content and sodium content per site, per month. | The intervention increased average number of “Right Choice” items purchased from vending machines from 9.9% to 35%. Percentage change in average monthly revenue was not significantly different between baseline and post-intervention (95% CI = −12.6 to 7.8, p = 0.5766). On average, the intervention reduced average fat content by 27.4% per month (95% CI = −37.4 to −15.9, p < 0.0001), sugar content by 11.8% per month (95% CI = −22.0 to −0.3, p = 0.0447), sodium content by 25.9% per month (95% CI = −33.9 to 17.0, p < 0.0001) and calorie content by 16.7% per month (95% CI = −25.5 to −6.8, p = 0.0016). Beverage profit declined by 11.1% (95% CI = −19.9 to −1.3, p = 0.0274) while number sold increased by 16.2% (95% CI = 3.7 to 30.2, p = 0.0100). | ∅ |

| James et al. (2017) [35], UK | Observational, 2 weeks | Assess adherence to NICE quality statements 1–3 of quality standard 94 at two NHS hospitals. | n = 30 hospital food outlets | Food environments were assessed using the Consumer Nutrition Environment Tool. Adherence to quality statements was measured. Statement 1 regarding healthy options in vending machines, statement 2 about nutritional information on menus and statement 3 regarding prominent display of healthy options. | Proportion of healthy and less healthy options in vending machines, clarity of nutrition information on menus and prominence of healthy food and beverages displayed. | 10% of food products and 53% of drinks in vending machines were considered healthy, making adherence to quality statement 1 poor. Food items were given a C-NET score of 18.3. Nutritional information was not available on menus at either facility, so adherence to quality statement 2 was also poor. Adherence to quality statement 3 was inconsistent, as both healthy and less healthy products were prominently displayed in cafeterias. 25% of cafeteria options were healthy. | ∅ |

| Jaworowska et al. (2018) [44], UK | Observational, 2 months | Describe nutritional quality of hot lunches in NHS hospital staff canteens. | n = 8 hospitals | Nutritional composition of canteen meals was assessed using meal samples from each canteen. | Energy, protein, total fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, fibre and sodium content of meals. | Meals containing meat had a higher energy density than vegetarian meals and were also higher in salt content (0.61 vs. 0.49 g; p < 0.05) and protein per 100g (9.8 vs. 4.8 g; p < 0.05). Significant variation in nutritional composition between different meals. According to standard cafeteria portion sizes, 67% of meat-based and 80% of vegetarian meals were high in saturated fat, while 69% of meat-based and 43% of vegetarian dishes were high in salt (red light according to the traffic light labelling system). Meals varied significantly between hospitals, especially per portion. | ∅ |

| Jilcott Pitts et al. (2016) [19], USA | Observational, short duration | Describe barriers and facilitators to the implementation of healthy service guidelines and strategies for health promotion. | n = 9 food service managers and operators | Information about hospital size, types of food available and current nutrition initiatives was gathered via a quantitative survey and more in-depth information was obtained from qualitative interviews. | Difficulty or ease of guideline implementation, price outcomes, barriers and facilitators to implementation and potential behavioural design strategies to promote healthy eating. | Challenges raised regarding implementation of guidelines including profit implications, customer dissatisfaction and difficulties with changing obligations to food strategies. Suggested strategies to encourage healthier choices included signage and icons on healthier items, positioning of healthy options and marketing techniques. Additional training costs were anticipated to arise from altering the food environment. | ∅ |

| Kibblewhite et al. (2010) [45], UK | Observational, short duration | Describe products available in vending machines close to paediatric wards and outpatient clinics. | n = 13 hospitals | Percentages of healthy and unhealthy vending machine items accessible to children were calculated. | Number of healthy and unhealthy items in vending machines and advertising for unhealthy brands. | In paediatric clinics, 13% of the drinks-only machines contained over 50% healthy options, while none of the food-only machines reached this target. The mixed food and drink machine met the target for drinks, but not food. In other areas of the hospital which were accessible to children, 9% of drinks machines contained over 50% healthy options compared to 27% for food machines. Mixed machines contained 50% healthy drinks but not food. 55% of machines in paediatric clinics and 72% in other areas displayed commercial logos, mostly associated with unhealthy products. | ∅ |

| LaCaille et al. (2016) [20], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 12 months | Assess the efficacy of Go!, an obesity-prevention programme. | n = 900 hospital and primary care clinic employees | A multi-component intervention was implemented, including traffic light labelling, choice architecture, pedometer usage and signage was launched. | Weight, BMI, waist circumference, physical activity levels and dietary behaviour after 6 months and 1 year | No significant change in weight (95% CI = −1.13, 1.56, p = 0.76) or BMI between groups (95% CI = −0.17, 2.39, p = 0.09) or in weight (95% CI = −0.36, 0.89, p = 0.40) or BMI (95% CI = −0.27, 0.95, p = 0.27) over time. The control group had a significantly greater decrease in waist circumference than the intervention group at 6 months (95% CI = 1.28 to 4.72, p = 0.001) but not at 12 months (95% CI = −1.06, 2.16, p = 0.51). There was a significant decrease in fruit and vegetable intake over 12 months in the intervention group (95% CI = −13.13, −2.23, p = 0.007), but consumption of foods high sugar and fat, like cookies, cakes and brownies, also significantly decreased (95% CI = −0.12, −0.01, p = 0.02). The intervention caused employees to view their employer as more committed to improving health and wellbeing (95% CI = 0.06, 0.23, p = 0.002) and 86% wanted the intervention to continue. | ∅ |

| Lawrence et al. (2009) [46], USA | Observational, short duration | Describe the range of healthy and unhealthy vending machine options and healthcare settings. | n = 19 healthcare facilities | Numbers of healthy and unhealthy products in vending machines were recorded and the quality and quantity of food products were compared between 3 types of environment. | Percentage of healthy options in vending machines, advertising and implementation of standards. | In hospitals and clinics, carbonated beverages were the most prevalent drink, accounting for 30% of drinks in hospitals and 38% in clinics). 81% of food across all sites did not adhere to standards, 75% of vending machines displayed advertisements for carbonated beverages and 60% of facilities with vending machines were in the process of adopting nutritional standards for the machines. | ∅ |

| Lederer et al. (2014) [21], USA | Observational, short duration | Describe the nutritional knowledge, practices and attitudes of hospital cafeteria managers in hospitals following the Healthy Hospitals Food Initiative (HHFI). | n = 17 cafeteria managers | A 22 question survey was delivered to participants who approved menus, had influence over food purchases and monitored food preparation. | Nutritional practices, standards and policies. | 4 of 17 participants said that their cafeteria followed hospital nutrition standards. 13 claimed to think about nutrition when planning menus, but most respondents ranked consumer preferences and cost as the 2 main considerations. 14 participants reported reducing sodium content of meals by cooking from scratch, buying products with lower sodium content and decreasing the salt content of recipes. 16 respondents cited consumer-related factors as limitations to healthy food implementation, such as lack of demand, customer satisfaction and lack of consumer education around healthy eating. Environmental factors were also a concern for 6 participants, such as an inability to move cafeteria fixtures to make healthy options more prominent. | ∅ |

| Lesser et al. (2012) [47], USA | Observational, short duration | Describe the quality of the food environments in outlets at a children’s hospital | n = 14 hospitals | The Nutrition Environment Measures Study in Restaurants was adapted for use in cafeterias. Items in hospital cafeterias were scored according to healthy or unhealthy status. | Nutritional quality of food in hospital cafeterias and healthy eating prompts. | Majority of venues offered healthy options, like low-fat milk, fresh fruit and a salad bar. Around 50% of cafeterias displayed point-of-purchase nutritional information, while less than 33% displayed signage promoting healthy menu choices. High-calorie options were available near point-of-purchase in 81% of venues, 50% offered discounts for multiple purchases, 38% displayed signage promoting unhealthy eating and 50% had no healthy hot meals. NEMS-C scores ranged from 13 to 30, with a mean of 19.1. | ∅ |

| Liebert et al. (2013) [22], USA | Mixed Methods, 2 years | Research and plan the Better Bites intervention programme to improve food choices of hospital employees. | n = 100 hospital employees | Employees were interviewed using the Nutrition Environment Measures Study in Restaurants and other surveys. Best practices were identified for planning and developing the Better Bites intervention. | Barriers and facilitators to healthy eating, perceptions of healthy food availability and likelihood of behaviour modification following interventions. | Majority of respondents supported the intervention but concerns were raised about profits, resources and ability to change eating behaviours. 82% of respondents were concerned about eating well and 83% reported being more likely to buy healthy items if cheaper than unhealthy items. 73% in favour of reducing healthy option prices and increasing unhealthy option prices. | ∅ |

| Mazza et al. (2017) [36], USA | Quasi-Experimental, short duration (around 15 days per intervention) | Comparing the impacts of a range of interventions, combined with traffic light labelling, on beverage and crisp (potato chip) sales. | n = 1 hospital food outlet | Interventions, such as price increases, health messaging, social norm messaging and grouping items into nutritional categories, were assessed for efficacy alongside a traffic light labelling intervention. | Daily number of healthy (green-labelled) purchases. | Traffic light labelling increased healthy beverage purchases by 2.9% compared to a price increase alone (p < 0.0001). When labelling and price changes were combined with subsequent interventions, colour grouping, social norm feedback and oppositional pairing reduced healthy beverage purchases by 2% (p < 0.0001), 1.7% (p < 0.01) and 6.9% (p = 0.01), respectively. For crisps, traffic light labelling increased percentage of healthy crisps sold by 5.4% (p = 0.001), compared to a sugar sweetened beverage price increase. When water price decreased, healthy crisp sales decreased by 5.9% (p = 0.003). Health messaging increased healthy crisp sales by 6% compared to control conditions (p = 0.004). | ∅ |

| McSweeney et al. (2018) [23], UK | Observational, short duration | Assess parental perspectives of food available in a children’s hospital and the barriers and facilitators to healthy eating. | n = 18 parents | Parents were interviewed regarding ease of healthy eating in the hospitals until no new themes were raised. | Themes centred around food accessibility and nutritional quality of food in hospitals. | Purchases were influenced by cost and speed. Parents described the food choice as restrictive, especially for children, vegetarians and those trying to eat healthier. Quality of food was said to vary between outlets and concerns about freshness, presentation and location of unhealthy options were raised. Maintenance of a healthy diet was considered difficult, as food available contradicted healthy eating messages shown on signs. A discount or loyalty card was proposed to make healthy food cheaper to repeat visitors. | ∅ |

| Mohindra et al. (2021) [37], UK | Observational, 2 weeks | Describe nutritional quality of products available in a dental hospital, along with the price and positioning of high fat, salt and sugar products. | n = 1 hospital food outlet | An audit of coffee shop food and beverage options was carried out using Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) indicator 1b targets for 2018/19 | Nutritional content of packaged food and drinks and fresh food, total sugar content in products and the price, quantity and variety of each product category. | A variety of pre-packaged sandwiches, wraps and salads was available, compared to just 1 packaged vegetable product, 3 packaged fruit products and 3 fresh fruit products. 42% of packaged sandwiches, wraps and salads contained less than 400 kcal and below 5 g saturated fat per 100 g. 50% of cakes and 66% of biscuits adhered to the CQUIN guideline of containing less than 250 kcal per portion and 12% of cakes contained more sugar per portion than the daily recommended sugar intake from SACN. All crisps and popcorn met targets for saturated fat, while 73% contained less than the PHE salt target. All cold drinks met the CQUIN targets per 100 mL, but portion sizes varied widely and, as such, so did sugar content per portion. All hot drinks met the CQUIN targets. Unhealthy foods were displayed prominently compared to fresh fruit and packaged fruit was more expensive than packaged biscuits. Low-fat sandwiches were also more expensive than high-fat sandwiches. | ∅ |

| Moran et al. (2016) [48], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 3 years | Implement the Healthy Hospitals Food Initiative (HHFI) in public and private hospitals to establish nutrition standards and assess outcomes. | n = 40 hospitals | HHFI implementation was supported by dieticians, promotional materials and monthly progress reports to identify achievements and next steps. | Degree of HHFI implementation and nutritional quality of food options. | At baseline, all public hospitals (n = 16) had implemented standards for patient meals and vending machines, but none had implemented cafeteria standards. No hospital met the criteria for sodium or whole grains, and none offered an affordable healthy meal. Following intervention, 12 public hospitals met cafeteria standards, while 71% of private hospitals had implemented standards for patient meals, 58% for beverage vending machines, 50% for food vending machines and 67% for cafeterias. 21% of hospitals achieved sodium standards, 61% achieved standards for whole grains and 68% offered a healthy, affordable meal. | + |

| Mulder et al. (2020) [49], USA | Observational, 11 months | Describe national prevalence of workplace policies, practices and interventions to support employee health. | n = 338 hospitals | Senior hospital employees responded to the Workplace Health in America survey. | Hospital size and worksite health-promotion factors. | 81.7% of hospitals provided health promotion or wellness programmes in the previous year and likelihood of implementation varied based on hospital size (p < 0.01) and type (p < 0.05). Of those which offered programmes, 53.7% provided healthy diet advice (95% CI, 47.6–59.8%) and 59.9% had programmes to tackle obesity (95% CI, 53.9–65.9%). Of the hospitals which had wellness programmes and contained food outlets, 48.6% displayed nutritional information about calories, sodium or fat (95% CI, 42.3–54.8%), 54.7% used symbols to identify healthy choices (95% CI, 48.4–61.0%) and 19.2% subsidised healthy foods and beverages (95% CI, 14.2–24.1%). | + |

| Patsch et al. (2016) [24], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 1 year | Assess the impact of subsidisation of healthy food and taxation of unhealthy food on sales and financial outcomes. | n = 2800 hospital visitors and employees | Three food items were paired with healthier ‘Better Bites’ alternatives at two hospitals (PH and SFMC). Products were labelled as such and signage was added to canteens. Healthy product cost decreased by 35%, while unhealthy product cost increased by 35%. | Average weekly healthy (Better Bites) and less healthy sales, change in the proportion of healthy and less healthy products sold at each facility and financial outcomes. | At PH, relative traditional burger sale decreased by 47.9% (z = ± 35.85, p < 0.001) while the Better Bites option experienced a relative increase of 600% (z = ± 35.85, p < 0.001). Better Bites salad sales demonstrated a relative increase of 2.6% (z = ± 1.18, p = 0.238). At SFMC, proportion of traditional burger sales experienced a relative decrease of 20.4% (z = ± 14.87, p < 0.001) and the Better Bites burger demonstrated a relative increase of 371.2% (z = ± 14.87, p < 0.001), but sales remained lower than those of traditional burgers. At this site, Better Bites salad sales showed a relative increase of 71.1% (z = ± 5.32, p < 0.001). | ∅ |

| Pechey et al. (2019) [38], UK | RCT, 28 weeks | Assess the impact of altering the absolute and relative availability of healthier and less healthy vending machine products. | n = 10 hospital food outlets | Vending machines were subjected to five conditions and 20% of items were changed in each condition. Proportion of healthier and less healthy items available was altered each time. | Energy purchased from each vending machine under every condition and number of products vended each week. | Altering the proportion of healthy and unhealthy options did not significantly alter energy purchased from food (decrease less healthy: p = 0.407, increase healthier: p = 0.103, decrease healthier: p = 0.350, increase less healthy: p = 0.180). When the number of unhealthy beverages decreased, energy purchased from beverages decreased by 53% (p = 0.001). Total sales did not decrease. | + |

| Public Health England (2018) [39], UK | Quasi-Experimental, 9 months | Assess the impact of nutrition standard implementation and choice architecture on the nutritional quality of vending machine products. | n = 17 food outlets | In phase 1, vending machine content was altered to adhere to best practice Government Buying Standards for Food and Catering but healthy items were displayed less prominently. In phase 2, standards were upheld and healthier items were displayed more prominently. | Number of items sold, mean energy content per product and mean sugar content per product. | In drinks machines, total sales increased by 2.5% as fewer sugar-sweetened beverages and more ‘diet’ beverages were sold. Energy per item sold decreased (−36.2%), along with total sugar content (−36.4%). In food machines, overall sales decreased throughout the intervention (−3.2% in phase 1, −11.8% between phase 1 and 2), mainly due to reduced purchase of crisps (−29.1% in phase 1, −23.1% between phase 1 and 2). Confectionary and dried fruit and nuts sales increased in phase 1 (+14.2% and +23.2%) and decreased slightly (but remained above baseline) in phase 2 (−8.2% and −0.8%) and total energy from food decreased in phase 1 (−10.5%) and phase 2 (−9.5%). | ∅ |

| Sato et al. (2013) [54], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 12 weeks | Assess the impact of food labelling on the purchase of healthier entrees in cafeterias and on financial outcomes. | n = 1 hospital food outlet and n = 131 participants surveyed | Following baseline data collection from receipts, labels were added to entrees, displaying information on calorie, fat and sodium content. Customers were surveyed on their usage of these labels. | Change in the nutritional content of purchases pre- and post-intervention and customer preferences on labelling and views regarding the influence of labelling. | Mean percentage of healthier options sold increased by 0.7% while regular menu sales decreased by 0.7% (p = 0.837). Overall, total entrée sales decreased by around 8% (p < 0.0001) and average price increased by 50 cents. 77% of customers who purchased entrees claimed to have noticed the labels and at least 71% of these respondents expressed positive feelings towards the labels. 50% of those who noticed labels and purchased an entrée claimed that labels influenced their purchase, persuading them to select healthier options. | ∅ |

| Sharma et al. (2016) [50], USA | Observational, 2 months | Describe current policies and practices associated with nutrition and physical activity environments in hospitals and compare them between facilities. | n = 5 hospitals | The Environmental Assessment Tool was used to assess healthy food availability in six cafeterias and six vending machines. Mean score was calculated at each healthcare facility. | Environmental Assessment Tool factors, such as physical activity and nutrition support. | All hospitals offered nutrition education classes and provided healthy vending machines and cafeteria options. Healthy food availability scores ranged from 62–75% and varied within hospitals. Healthy food availability in vending machines scored 13–36%, while healthy drink availability scored between 0–40%. | ∅ |

| Simpson et al. (2018) [40], UK | Quasi-Experimental, 6 months | Assess the feasibility of increasing proportion of healthy options in a hospital shop and the impact on financial outcomes and consumer acceptability. | n = 1 hospital food outlet | Portion sizes, promotions, prices, positioning and healthy option availability were adjusted to diminish barriers and implement facilitators to healthy eating. Intervention results were assessed soon after implementation and at a later date. | Relative sales of healthy food products, change in sales within food categories and change in profits. | Adding fruit to the meal deal increased units of fruit sold from 40 to over 900 per week. Total sales increased by 11% but no significant change in relative proportion of healthy food sales. In follow-up, sales increased by 27% but change in relative proportion of healthy food sales remained unchanged. Sales of sweets and chocolate decreased, but sales of other unhealthy products did not. 35% of respondents said the shop sold a good range of healthy options pre-intervention, compared to 60% post-intervention. | ∅ |

| Sonnenberg et al. (2013) [25], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 3 months | Assess the impact of product labelling on consumer awareness of healthy purchases. | n = 204 (baseline) n = 253 (following intervention) hospital employees and visitors | Traffic light labelling and signage were introduced. A dietician was present in the first two weeks of intervention and nutritional information flyers were made available. Consumers were surveyed following purchase of items. | Public perspectives on important factors when purchasing food and beverages, nutritional value of products and the influence of traffic light labelling on purchases. | At baseline, 46% of respondents stated health and nutrition were important factors when making food choices, increasing to 61% following intervention (p = 0.004). Taste (p = 0.04) and price (p = 0.02) also became more important, while convenience became slightly less important (p = 0.06). Increased participants reporting usage of nutritional information when making choices (15% to 33%, p < 0.001). Those who noticed and were influenced by labels bought more green-labelled items and fewer red-labelled items compared to those who did not (p < 0.001). | ∅ |

| Stead et al. (2020) [41], UK | Mixed Methods, 18 months (short reassessment 1 year later) | Describe the process of Healthcare Retail Standard implementation and how the standards impact healthy product promotion. | n = 17 hospital food outlets | Data on chocolate and fresh fruit was gathered following implementation of the Healthcare Retail Standards (HRS) and interviews were conducted with managers to understand awareness and attitudes regarding the standards. | Number of relevant products on display and number of promotions for relevant products. | 12 of 13 shops achieved compliance with the HRS. Mean number of fruit products available did not change, while mean number of chocolate products decreased from an average of 60 to 29. Chocolate promotions in shops decreased from 166 to 38. Managers raised concerns about reduced uptake of meal deals. Allowing introduction of baked crisps into the meal deal slightly increased sales, but not to pre-intervention levels. | ∅ |

| Stites et al. (2015) [26], USA | Mixed Methods, 12–16 weeks | Assess the impact of mindfulness and pre-ordering meals on nutritional quality of purchases by hospital employees. | n = 26 hospital employees | In the full-intervention, mindful eating educational sessions were combined with encouragement to pre-order canteen meals. Vouchers were also issued. In the partial intervention, vouchers were not issued. Mindful Eating Questionnaires were administered at the beginning and end of the study. | Amount of energy and fat in lunches purchased by employees. | Average calorie content of lunches was 601 kcal and fat content was 4.9 g for the intervention group compared to 745.7 kcal (95% CI = −254.0 to −35.1, p = 0.01) and 13.8 g (95% CI = −15.2 to −2.6, p = 0.005) for the delayed treatment group. Calorie (95% CI = −81.3 to −52.6, p < 0.001) and fat content (95% CI = −4.1 to −2.8, p < 0.001) also decreased when the financial incentive was removed. Mindful eating behaviours increased from pre- to post-intervention (p < 0.001), but weight loss was not statistically significant e (p = 0.099). 92% of participants expressed interest in using a pre-ordering system in the future. | + |

| Sustain (2017) [51], UK | Observational, short duration | Describe current availability of healthy food and drinks in hospitals and determine hospital adherence to nutritional standards. | n = 30 hospitals | Surveys were sent to hospitals and assessed fresh food availability, healthy options and access to facilities during breaks. | Information on hospital food standards and types of food available to staff and visitors. | 50% of hospitals adhered to all five standards stated in the NHS contract, while 67% reported meeting or working towards health and wellbeing CQUIN targets. 40% of facilities had 24-h access to healthy foods, 25% met the criteria for having a food and drink strategy and 77% offered fresh food to staff. Two hospitals met all of the criteria for healthy food available to staff and visitors and 23 met the goal of having two portions of vegetables per main meal. Six hospitals had 70% or more products in hospital shops with green or orange traffic light labels. Vending machines selling mostly healthy options (n = 138) were more prevalent than those selling less healthy options (n = 90); 21 hospitals offered meal deals, including healthy options. | ∅ |

| Thorndike et al. (2014) [30], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 2 years | Assess the impact of traffic light labelling and choice architecture on hospital cafeteria sales. | n = 2285 hospital employees | Traffic light labelling was introduced and, after three months, a choice architecture intervention was also introduced. | Proportion of healthy and unhealthy sales every 3 months. | After one year, proportion of red-labelled items sold decreased from 24% to 21% (p < 0.001) and proportion of green-labelled items increased from 41% to 45% (p < 0.001). After two years, proportion of red-labelled items sold remained the same, while proportion of green-labelled items increased to 46% (p < 0.001). Results were statistically similar among all populations and sales were stable for two years. | ∅ |

| Thorndike et al. (2016) [29], USA | RCT, 6 months | Investigate the impact of social norm feedback and financial incentives on nutritional quality of purchases. | n = 2672 hospital employees | Participants were randomised to three groups, feedback (monthly comparison to other employee purchases), feedback and incentive (financial reward for healthy purchases) or control | Proportion of healthy items bought at baseline and at end of intervention. | The feedback incentive condition led to a 2.2% in green-labelled purchases (p = 0.03) compared to 0.1% for the control. The feedback only condition led to a non-signifcant1.8% increase (p = 0.03). There was a significant relationship between health classification at baseline and the impact of interventions on food choices (p < 0.001). | + |

| Thorndike et al. (2019) [27], USA | Observational, 2 years | Investigate the relationship between workplace cafeteria healthy eating programmes and reduced calorie purchases among employees throughout a two year intervention. | n = 5695 hospital employees | Sales data was gathered before and after implementation of traffic light labelling. | Calories sold at baseline and end of intervention, plus weight change of employees. | After one year, mean calorie content per transaction decreased by 19 kcal from baseline (95% CI, −23 to −15 kcal, p < 0.001). After two years, there had been a mean decrease of 35 kcal, with red-labelled item purchases decreasing by 42 kcal per transaction from baseline (95% CI, −45 to −39 kcal, p < 0.001). The dynamic model suggested that frequent users of the hospital cafeteria would lose 1.1 kg in one year and 2 kg in three years as a result of cafeteria interventions, assuming no other changes to eating or exercising behaviour. | + |

| Thorndike et al. (2021) [28], USA | RCT, 2 years | Assess the impact of an automated behavioural intervention on weight status and nutritional intake of hospital employees. | n = 602 hospital employees | Two emails were sent per week, providing feedback on purchasing behaviour and offering personalised advice. 1 letter was also sent per month, comparing participants to peers and offering financial incentives for healthy choices. | Change in weight from baseline to 12 months and 24 months, cafeteria purchases and calories purchased per day. | After 1 year (95% CI, −0.6 to 1.0, p = 0.70) and 2 years (95% CI, −0.3 to 1.4, p = 0.20), there was no significant difference in weight change between the intervention and control groups. Following the first year, purchases of green-labelled items had increased by 7.3% (95% CI, 5.4 to 9.3) and purchases of red-labelled items had decreased by 3.9% compared to baseline (95% CI, −5.0 to −2.7). Number of calories purchased per day decreased by 49.5 kcal compared to the control group (95% CI, −5.0 to −2.7). Differences remained significant after 2 years. After 1 year, 92% of survey respondents in the intervention group stated that at least one of the intervention methods had supported healthy decision-making. | + |

| Webb et al. (2011) [55], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 3 months | Gather views of hospital food outlet users and assess the impact of calorie-labelling on purchasing behaviour. | n = 6 hospital food outlets and n = 554 survey respondents | Cafeterias were subjected to one of three conditions: No labelling, calorie and nutrient labelling on posters and labelling on posters in addition to point-of-purchase menu board labelling. | Attitudes, awareness and usage of calorie information by consumers and the daily number and type of purchases made. | 69% of survey respondents using food outlets with menu boards and posters noticed calorie information compared to 58% using outlets with just posters. 32% of respondents noticed calorie information and a third of these participants indicated that it influenced their purchases. Average number of daily purchases remained the same. Proportion of lower-calorie side dishes purchased increased by 4.8% at the menu-board site and decreased by 4.8% at the no labelling site (p = 0.0007). Proportion of low-calorie snacks purchased increased by 1.3% at the menu board site and decreased by 8.1% at the no labelling site (p < 0.006). Changes to entrée purchases were modest. | ∅ |

| Whitt et al. (2018) [42], USA | Quasi-Experimental, 4 months | Compare the impacts of traffic light labelling and cartoon labelling on food choices in a children’s hospital cafeteria. | n = 1 hospital food outlet | Products were given a traffic light colour sticker for unhealthy, neutral and healthy, or a Spongebob Squarepants sticker for healthy items. | Proportion of daily healthy, neutral and unhealthy purchases. | Traffic light labelling led to the lowest number of unhealthy food purchases, at 30%, which was significantly lower than the 37% value at baseline (p < 0.001). Cartoon labelling increased the number of unhealthy purchases, with a 5% increase from washout (χ2 = 5.73 (p = 0.057)). | ∅ |

| Winston et al. (2013) [52], USA | Observational, 4 months | Assess the impact of socioeconomic status of an area on hospital nutrition composite scores. | n = 39 hospitals | The Hospital Nutrition Environment Scan for Cafeterias, Vending Machines and Gift Shops was used to score the hospital food environment. | Barriers and facilitators for a healthy diet. | Average score was less than 25% of possible points and were higher for vending machines (33%) than for cafeterias or gift shops. There was no significant association between socioeconomic status of the area and the nutrition composite score. Less than half of the shelf space in cafeterias was used for healthier items and 85% of cafeterias displayed unhealthy options near the point-of-purchase. Use of a contracted food service was linked to provision of a healthy combination meal and the availability of nutritional information. | ∅ |

References

- National Health Service. Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet, England. 2020. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/england-2020 (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- CDC/National Center for Health Statistics. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm (accessed on 8 November 2020).

- Pi-Sunyer, F.X. The Obesity Epidemic: Pathophysiology and Consequences of Obesity. Obes. Res. 2002, 10, 97S–104S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. Health Matters: Obesity and the Food Environment. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment--2 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Kim, D.D.; Basu, A. Estimating the Medical Care Costs of Obesity in the United States: Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis and Empirical Analysis. Value Health 2016, 19, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.G.; Wills, J.; Mahoney, C.; Hoyle, L.; Kelly, M.; Atherton, I.M. Obesity prevalence among healthcare professionals in England: A cross-sectional study using the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health England. A Quick Guide to the Government’s Healthy Eating Recommendations; Public Health England: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Available online: http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/ (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Anderson Steeves, E.; Martins, P.A.; Gittelsohn, J. Changing the Food Environment for Obesity Prevention: Key Gaps and Future Directions. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgoine, T.; Forouhi, N.G.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Monsivais, P. Associations between exposure to takeaway food outlets, takeaway food consumption, and body weight in Cambridgeshire, UK: Population based, cross sectional study. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2014, 348, g1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maile, E.K.T.; MacMullen, H.; Mytton, O.; Ruddle, K. ‘Healthy Hospitals’ Initiative is Bearing Fruit. Available online: https://www.hsj.co.uk/leadership/healthy-hospitals-initiative-is-bearing-fruit/5068010.article (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Mourad, O.; Hammady, H.; Zbys, F.; Ahmed, E. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- EndNote X9; Clarivate Analytics: London, UK, 2018.

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Evidence Analysis Manual: Steps in the Academy Evidence Analysis Process. Available online: https://www.andeal.org/vault/2440/web/files/2016_April_EA_Manual.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The, P.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, M.L.; Lee, K.; Loglisci, R.; Righter, A.; Hipper, T.J.; Cheskin, L.J. Consumer Understanding of Calorie Labeling: A Healthy Monday E-Mail and Text Message Intervention. Health Promot. Pract. 2015, 16, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, M.A.R.; Hoyle, L.P.; Mahoney, C.; Kyle, R.G. Strategies to promote nurses’ health: A qualitative study with student nurses. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 48, 102860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.M.; Foltz, J.L.; Onufrak, S.; Belay, B. Health-promoting environments in U.S. medical facilities: Physician perceptions, DocStyles 2012. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Graham, J.; Mojica, A.; Stewart, L.; Walter, M.; Schille, C.; McGinty, J.; Pearsall, M.; Whitt, O.; Mihas, P.; et al. Implementing healthier foodservice guidelines in hospital and federal worksite cafeterias: Barriers, facilitators and keys to success. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaCaille, L.J.; Schultz, J.F.; Goei, R.; LaCaille, R.A.; Dauner, K.N.; de Souza, R.; Nowak, A.V.; Regal, R. Go!: Results from a quasi-experimental obesity prevention trial with hospital employees. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, A.; Toner, C.; Krepp, E.M.; Curtis, C.J. Understanding hospital cafeterias: Results from cafeteria manager interviews. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2014, 20, S50–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebert, M.L.; Patsch, A.J.; Smith, J.H.; Behrens, T.K.; Charles, T.; Bailey, T.R. Planning and development of the Better Bites program: A pricing manipulation strategy to improve healthy eating in a hospital cafeteria. Health Promot. Pract. 2013, 14, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McSweeney, L.; Spence, S.; Anderson, J.; Wrieden, W.; Haighton, C. Parental perceptions of onsite hospital food outlets in a large hospital in the North East of England: A qualitative interview study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patsch, A.J.; Smith, J.H.; Liebert, M.L.; Behrens, T.K.; Charles, T. Improving Healthy Eating and the Bottom Line: Impact of a Price Incentive Program in 2 Hospital Cafeterias. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenberg, L.; Gelsomin, E.; Levy, D.E.; Riis, J.; Barraclough, S.; Thorndike, A.N. A traffic light food labeling intervention increases consumer awareness of health and healthy choices at the point-of-purchase. Prev. Med. 2013, 57, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stites, S.D.; Singletary, S.B.; Menasha, A.; Cooblall, C.; Hantula, D.; Axelrod, S.; Figueredo, V.M.; Phipps, E.J. Pre-ordering lunch at work. Results of the what to eat for lunch study. Appetite 2015, 84, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Gelsomin, E.D.; McCurley, J.L.; Levy, D.E. Calories Purchased by Hospital Employees after Implementation of a Cafeteria Traffic Light–Labeling and Choice Architecture Program. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e196789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; McCurley, J.L.; Gelsomin, E.D.; Anderson, E.; Chang, Y.; Porneala, B.; Johnson, C.; Rimm, E.B.; Levy, D.E. Automated Behavioral Workplace Intervention to Prevent Weight Gain and Improve Diet: The ChooseWell 365 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2112528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Riis, J.; Levy, D.E. Social norms and financial incentives to promote employees’ healthy food choices: A randomized controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2016, 86, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorndike, A.N.; Riis, J.; Sonnenberg, L.M.; Levy, D.E. Traffic-light labels and choice architecture: Promoting healthy food choices. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 46, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, J.L.; Powell, D.J. Prompting consumers to make healthier food choices in hospitals: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrick, J.W.; Bellini, S.G.; Spelman, J. Using the Hospital Nutrition Environment Scan to Evaluate Health Initiative in Hospital Cafeterias. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1855–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbel, B.; Taksler, G.B.; Mijanovich, T.; Abrams, C.B.; Dixon, L.B. Promotion of healthy eating through public policy: A controlled experiment. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 45, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Griffiths, M.L.; Powell, E.; Usher, L.; Boivin, J.; Bott, L. The health benefits and cost-effectiveness of complete healthy vending. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Birch, L.; Fletcher, P.; Pearson, S.; Boyce, C.; Ness, A.R.; Hamilton-Shield, J.P.; Lithander, F.E. Are food and drink retailers within NHS venues adhering to NICE Quality standard 94 guidance on childhood obesity? A cross-sectional study of two large secondary care NHS hospitals in England. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e018214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, M.C.; Dynan, L.; Siegel, R.M.; Tucker, A.L. Nudging Healthier Choices in a Hospital Cafeteria: Results from a Field Study. Health Promot. Pract. 2018, 19, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohindra, A.; Jie, J.G.H.; Lim, L.Y.; Mehta, S.; Davies, J.; Pettigrew, V.A.; Woodhoo, R.; Nehete, S.; Muirhead, V. A student and staff collaborative audit exploring the food and drinks available from a dental teaching hospital outlet. Br. Dent. J. 2021, 230, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechey, R.; Jenkins, H.; Cartwright, E.; Marteau, T.M. Altering the availability of healthier vs. less healthy items in UK hospital vending machines: A multiple treatment reversal design. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Hospital Vending Machines: Helping People Make Healthier Choices. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/726721/Leeds_Vending_v3.4.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Simpson, N.; Bartley, A.; Davies, A.; Perman, S.; Rodger, A.J. Getting the balance right-tackling the obesogenic environment by reducing unhealthy options in a hospital shop without affecting profit. J. Public Health (Oxf.) 2018, 40, e545–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, M.; Eadie, D.; McKell, J.; Sparks, L.; MacGregor, A.; Anderson, A.S. Making hospital shops healthier: Evaluating the implementation of a mandatory standard for limiting food products and promotions in hospital retail outlets. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitt, O.R.; Jilcott Pitts, S.B.; Rafferty, A.P.; Payne, C.R.; Ng, S.W. The effects of traffic light labelling versus cartoon labelling on food and beverage purchases in a children’s hospital setting. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivois-Shah, R.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Khandekar, S.P.; Howerter, A.L.; O’Connor, P.A.; Edwards, B.A. Impact of Healthy Vending Machine Options in a Large Community Health Organization. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworowska, A.; Rotaru, G.; Christides, T. Nutritional Quality of Lunches Served in South East England Hospital Staff Canteens. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibblewhite, S.; Bowker, S.; Jenkins Huw, R. Vending machines in hospitals—Are they healthy? Nutr. Food Sci. 2010, 40, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Boyle, M.; Craypo, L.; Samuels, S. The food and beverage vending environment in health care facilities participating in the healthy eating, active communities program. Pediatrics 2009, 123 (Suppl. 5), S287–S292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesser, L.I.; Hunnes, D.E.; Reyes, P.; Arab, L.; Ryan, G.W.; Brook, R.H.; Cohen, D.A. Assessment of food offerings and marketing strategies in the food-service venues at California Children’s Hospitals. Acad. Pediatr. 2012, 12, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, A.; Krepp, E.M.; Johnson Curtis, C.; Lederer, A. An Intervention to Increase Availability of Healthy Foods and Beverages in New York City Hospitals: The Healthy Hospital Food Initiative, 2010–2014. Prev. Chronic. Dis. 2016, 13, E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mulder, L.; Belay, B.; Mukhtar, Q.; Lang, J.E.; Harris, D.; Onufrak, S. Prevalence of Workplace Health Practices and Policies in Hospitals: Results from the Workplace Health in America Study. Am. J. Health Promot. 2020, 34, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Winston Paolicelli, C.; Jyothi, V.; Baun, W.; Perkison, B.; Phipps, M.; Montgomery, C.; Feltovich, M.; Griffith, J.; Alfaro, V.; et al. Evaluation of worksite policies and practices promoting nutrition and physical activity among hospital workers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2016, 9, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustain. Taking the Pulse of Hospital Food. Available online: https://www.sustainweb.org/publications/taking_the_pulse/ (accessed on 10 November 2020).

- Winston, C.P.; Sallis, J.F.; Swartz, M.D.; Hoelscher, D.M.; Peskin, M.F. Consumer nutrition environments of hospitals: An exploratory analysis using the Hospital Nutrition Environment Scan for Cafeterias, Vending Machines and Gift Shops, 2012. Prev Chronic. Dis. 2013, 10, E110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, J.P.; Chandra, A.; McManus, K.D.; Willett, W.C. Point-of-purchase price and education intervention to reduce consumption of sugary soft drinks. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, J.N.; Wagle, A.; McProud, L.; Lee, L. Food Label Effects on Customer Purchases in a Hospital Cafeteria in Northern California. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2013, 16, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.L.; Solomon, L.S.; Sanders, J.; Akiyama, C.; Crawford, P.B. Menu Labeling Responsive to Consumer Concerns and Shows Promise for Changing Patron Purchases. J. Hunger. Environ. Nutr. 2011, 6, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlouli, J.; Moravejolahkami, A.R.; Ganjali Dashti, M.; Balouch Zehi, Z.; Hojjati Kermani, M.A.; Borzoo-Isfahani, M.; Bahreini-Esfahani, N. COVID-19 and Fast Foods Consumption: A Review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2021, 24, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richardson, S.; McSweeney, L.; Spence, S. Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081566

Richardson S, McSweeney L, Spence S. Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(8):1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081566

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichardson, Sarah, Lorraine McSweeney, and Suzanne Spence. 2022. "Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review" Nutrients 14, no. 8: 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081566

APA StyleRichardson, S., McSweeney, L., & Spence, S. (2022). Availability of Healthy Food and Beverages in Hospital Outlets and Interventions in the UK and USA to Improve the Hospital Food Environment: A Systematic Narrative Literature Review. Nutrients, 14(8), 1566. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14081566