Dietary Behavior and Diet Interventions among Structural Firefighters: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

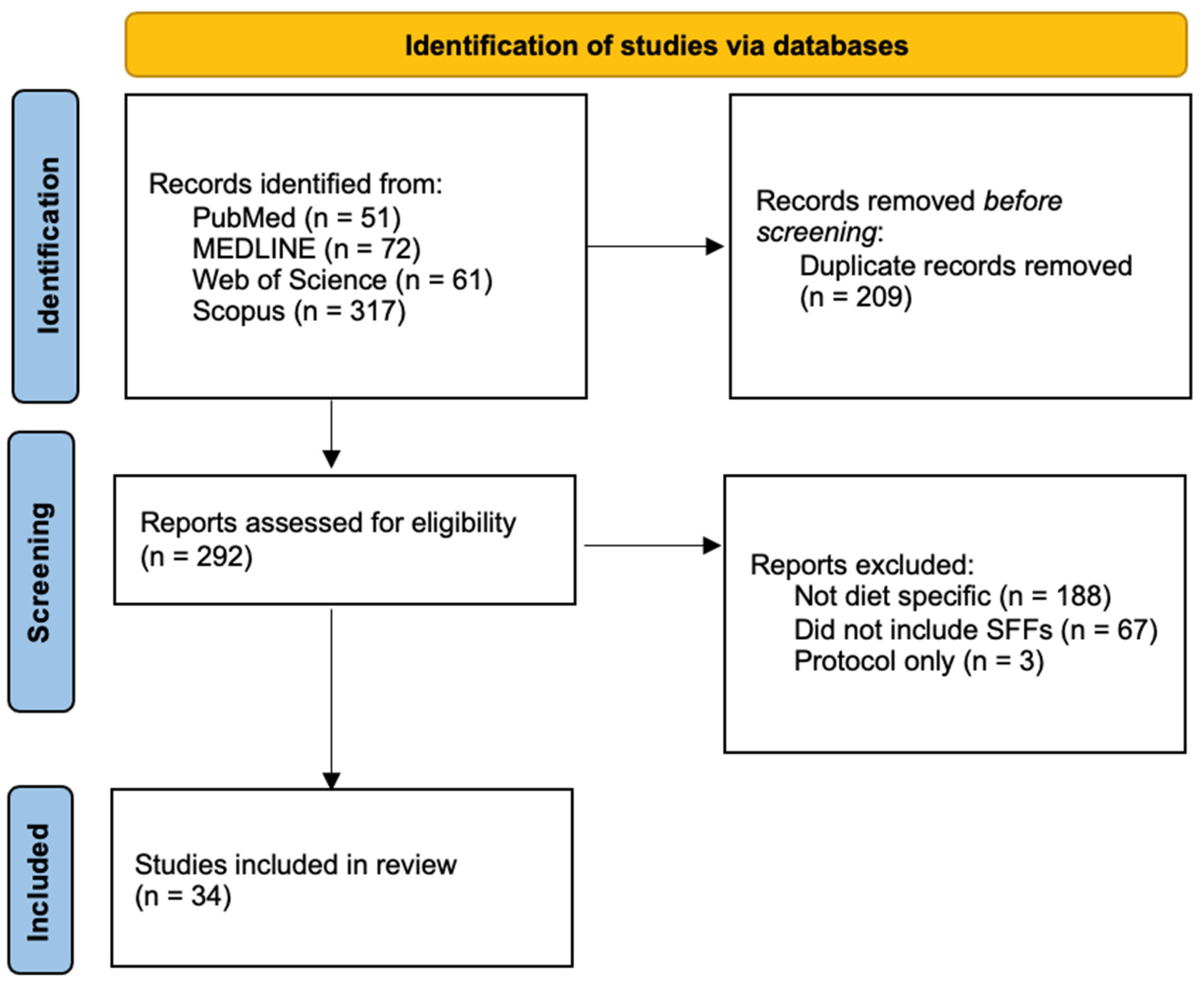

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Elegibility Criteria

2.2. Search and Selection Process

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Observational Studies

3.2. Intervention Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Fire Administration. National Fire Department Registry Quick Facts. 2022. Available online: https://apps.usfa.fema.gov/registry/summary#f (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- FEMA. Glossary. 2007. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/about/glossary (accessed on 12 March 2021).

- Evarts, B.; Stein, G.P. US Fire Department Profile 2018 Key Findings Background and Objectives; National Fire Protection Association: Quincy, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke, S.A.; Poston, W.S.; Jitnarin, N.; Haddock, C.K. Health concerns of the U.S. fire service: Perspectives from the firehouse. Am. J. Health Promot. AJHP 2012, 27, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIOSH. Firefighter Resources—Job Hazards. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/firefighters/hazard.html (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Eastlake, A.C.; Knipper, B.S.; He, X.; Alexander, B.M.; Davis, K.G. Lifestyle and safety practices of firefighters and their relation to cardiovascular risk factors. Work 2015, 50, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Cash, S.B.; Christophi, C.A.; Folta, S.; Moffatt, S.; Muegge, C.; Korre, M.; Mozaffarian, D.; Kales, S.N. Rationale and design of feeding America’s bravest: Mediterranean diet-based intervention to change firefighters’ eating habits and improve cardiovascular risk profiles. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2017, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NIOSH. Firefighter Resources, Cancer, and Other Illnesses. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/firefighters/health.html (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Daniels, R.D.; Kubale, T.L.; Yiin, J.H.; Dahm, M.M.; Hales, T.R.; Baris, D.; Zahm, S.H.; Beaumont, J.J.; Waters, K.M.; Pinkerton, L.E. Mortality and cancer incidence in a pooled cohort of US firefighters from San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia (1950–2009). Occup. Environ. Med. 2014, 71, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkerton, L.; Bertke, S.J.; Yiin, J.; Dahm, M.; Kubale, T.; Hales, T.; Purdue, M.; Beaumont, J.J.; Daniels, R. Mortality in a cohort of US firefighters from San Francisco, Chicago and Philadelphia: An update. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.L.; Franke, W.D. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in volunteer firefighters. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009, 51, 958–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ras, J.; Leach, L. Prevalence of coronary artery disease risk factors in firefighters in the city of Cape Town fire and rescue service—A descriptive study. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.L.; Fehling, P.C.; Frisch, A.; Haller, J.M.; Winke, M.; Dailey, M.W. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and obesity in firefighters. J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 908267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. NIOSH Alert—Preventing Fire Fighter Fatalities Due to Heart Attacks and Other Sudden Cardiovascular Events—NIOSH Publication Number 2007-133. 2007. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2007-133/pdfs/2007-133.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Soteriades, E.S.; Smith, D.L.; Tsismenakis, A.J.; Baur, D.M.; Kales, S.N. Cardiovascular disease in US firefighters: A systematic review. Cardiol. Rev. 2011, 19, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEMA. National Fire Department Registry Summary 2020: Fire Departments by Region. 2020. Available online: https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/firefighter-fatalities-2019.pdf?utm_source=website&utm_medium=pubsapp&utm_content=Firefighter%20Fatalities%20in%20the%20United%20States%20in%202019&utm_campaign=R3D (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Yang, J.; Farioli, A.; Korre, M.; Kales, S.N. Dietary Preferences and Nutritional Information Needs among Career Firefighters in the United States. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2015, 4, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Jin, Q.; Rainey, D.; Coyle, M.; Kales, S.N. Barriers and solutions to improving nutrition among fire academy recruits: A qualitative assessment. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddock, C.K.; Day, R.S.; Poston, W.S.; Jahnke, S.A.; Jitnarin, N. Alcohol use and caloric intake from alcohol in a national cohort of U.S. career firefighters. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2015, 76, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Farioli, A.; Korre, M.; Kales, S.N. Modified Mediterranean diet score and cardiovascular risk in a North American working population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.A.; Harrison, T.R.; Yang, F.; Wendorf Muhamad, J.; Morgan, S.E. Firefighter perceptions of cancer risk: Results of a qualitative study. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2017, 60, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Kontogeorgos, A.; Loizou, E. Behind the image: An investigation of Greek firefighter’s body mass index. Pakistan J. Nutr. 2017, 16, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robertson, A.H.; Larivière, C.; Leduc, C.R.; McGillis, Z.; Eger, T.; Godwin, A.; Larivière, M.; Dorman, S.C. Novel Tools in Determining the Physiological Demands and Nutritional Practices of Ontario FireRangers during Fire Deployments. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friel, J.K.; Gabriel, A.; Stones, M. Nutritional status of firefighters. Can. J. Public Health = Rev. Can. De Sante Publique 1988, 79, 275–276. [Google Scholar]

- Romanidou, M.; Tripsianis, G.; Hershey, M.S.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Christophi, C.; Moffatt, S.; Constantinidis, T.C.; Kales, S.N. Association of the Modified Mediterranean Diet Score (mMDS) with Anthropometric and Biochemical Indices in US Career Firefighters. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Mayer, J.M. Evaluating Nutrient Intake of Career Firefighters Compared to Military Dietary Reference Intakes. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatandoost, A.; Azadbakht, L.; Morvaridi, M.; Kabir, A.; Mohammadi Farsani, G. Association between Dietary Inflammatory Index and Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases among Firefighters. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershey, M.S.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Cassidy, A.; Moffatt, S.; Kales, S.N. Anthocyanin Intake and Physical Activity: Associations with the Lipid Profile of a US Working Population. Molecules 2020, 25, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnell, E.K.; Huggins, C.E.; Huggins, C.T.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Palermo, C.; Bonham, M.P. Influences on Dietary Choices during Day versus Night Shift in Shift Workers: A Mixed Methods Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, C.C.; Ferguson, S.A.; Aisbett, B.; Dominiak, M.; Chappel, S.E.; Sprajcer, M.; Fullagar, H.; Khalesi, S.; Guy, J.H.; Vincent, G.E. Hot, Tired and Hungry: The Snacking Behaviour and Food Cravings of Firefighters during Multi-Day Simulated Wildfire Suppression. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiwar, P.; Shah, N.; Black, T.; Caban-Martinez, A.J.; Steinberg, M.; Black, K.; Sackey, J.; Graber, J. Dietary Intake among Members of a Volunteer Fire Department Compared with US Daily Dietary Recommendations. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, H.S.; Smith, J.W.; Lamberth, J.; Fountain, B.J.; McAllister, M.J. A 28-Day Carbohydrate-Restricted Diet Improves Markers of Cardiometabolic Health and Performance in Professional Firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 3284–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranby, K.W.; MacKinnon, D.P.; Fairchild, A.J.; Elliot, D.L.; Kuehl, K.S.; Goldberg, L. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects) firefighter study: Testing mediating mechanisms. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliot, D.L.; Goldberg, L.; Kuehl, K.S.; Moe, E.L.; Breger, R.K.; Pickering, M.A. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects) firefighter study: Outcomes of two models of behavior change. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2007, 49, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.; Superko, H.R.; McCarthy, M.M.; Jack, K.; Jones, B.; Ghosh, D.; Richards, S.; Gleason, J.A.; Williams, P.T.; Dansinger, M. Cardiovascular Risk Factor Reduction in First Responders Resulting from an Individualized Lifestyle and Blood Test Program: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, R.C.; Vieira, A.; Marin, D.P.; Otton, R. Effects of chronic resveratrol supplementation in military firefighters undergo a physical fitness test--a placebo-controlled, double blind study. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2015, 227, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, S.L.; Phillips, J.S.; Twilbeck, T.J. Determining Best Practices to Reduce Occupational Health Risks in Firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2015, 29, 2041–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirlott, A.G.; Kisbu-Sakarya, Y.; Defrancesco, C.A.; Elliot, D.L.; Mackinnon, D.P. Mechanisms of motivational interviewing in health promotion: A Bayesian mediation analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goheer, A.; Bailey, M.; Gittelsohn, J.; Pollack, K.M. Fighting fires and fat: An intervention to address obesity in the fire service. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Elliot, D.L.; Thoemmes, F.; Kuehl, K.S.; Moe, E.L.; Goldberg, L.; Burrell, G.L.; Ranby, K.W. Long-term effects of a worksite health promotion program for firefighters. Am. J. Health Behav. 2010, 34, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, R.S.; Jahnke, S.A.; Haddock, C.K.; Kaipust, C.M.; Jitnarin, N.; Poston WS, C. Occupationally Tailored, Web-Based, Nutrition and Physical Activity Program for Firefighters: Cluster Randomized Trial and Weight Outcome. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Christophi, C.; Black, A.; Furtado, J.D.; Song, Y.; Magiatis, P.; Papakonstantinou, A.; Melliou, E.; Moffatt, S.; Kales, S.N. Assessing Validity of Self-Reported Dietary Intake within a Mediterranean Diet Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial among US Firefighters. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Song, Y.; Christophi, C.; Mofatt, S.; Rodriguez-Artalejo, F.; Kales, S.N. The Effects of a Mediterranean Diet Intervention on Targeted Plasma Metabolic Biomarkers among US Firefighters: A Pilot Cluster-Randomized Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.; Wong, A.; Cheung, K. A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial Feasibility Study of a WhatsApp-Delivered Intervention to Promote Healthy Eating Habits in Male Firefighters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.A.; Reeve, E.H.; Dickinson, R.L.; Carty, M.; Gilpin, J.; Feairheller, D.L. Civilians Have Higher Adherence and More Improvements in Health with a Mediterranean Diet and Circuit Training Program Compared to Firefighters. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2022, 64, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher Della Torre, S.; Wild, P.; Dorribo, V.; Amati, F.; Danuser, B. Eating Habits of Professional Firefighters: Comparison with National Guidelines and Impact Healthy Eating Promotion Program. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 61, e183–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman, H.S.; Smith, J.W.; Lamberth, J.; Fountain, B.J.; Bloomer, R.J.; Butawan, M.B.; McAllister, M.J. A 28-Day Carbohydrate-Restricted Diet Improves Markers of Cardiovascular Disease in Professional Firefighters. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2785–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Painting, firefighting, and shiftwork. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2010; Volume 98, pp. 9–764. [Google Scholar]

- Hershey, M.S.; Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ruiz-Canela, M.; Christophi, C.A.; Moffatt, S.; Martínez-González M, Á.; Kales, S.N. The Mediterranean lifestyle (MEDLIFE) index and metabolic syndrome in a non-Mediterranean working population. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2494–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Excessive Alcohol Use. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/alcohol.htm (accessed on 17 July 2021).

- Kniffin, K.M.; Wansink, B.; Devine, C.M.; Sobal, J. Eating Together at the Firehouse: How Workplace Commensality Relates to the Performance of Firefighters. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batch, J.T.; Lamsal, S.P.; Adkins, M.; Sultan, S.; Ramirez, M.N. Advantages and Disadvantages of the Ketogenic Diet: A Review Article. Cureus 2020, 12, e9639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snopek, L.; Mlcek, J.; Sochorova, L.; Baron, M.; Hlavacova, I.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Contribution of red wine consumption to human health protection. Molecules 2018, 23, 1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.K. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year | Study Design, Study Location | Study Objective | Study Population [Sample Size, Source Population, Age, Career Length, Sex, Race/Ethnicity] | Diet Pattern Assessment Tool | Key Results | Qualitative Narrative Assessment of Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang J et al., 2015 [17] | Cross-over; United States | To determine diet practice and diet preferences | n = 3127 (out of n = 3657); IAFF (professional) FF members; 42 ± 10 years; 92.6% male, 7.4% female; Race/ethnicity unspecified | 19-question questionnaire about type of diet—18 diets listed | 71% practiced no diet pattern, 9% Paleo, 8% low carbohydrate, 4% low fat, <2% commercial, 1% Mediterranean; 20.4% assessed self-knowledge of diet sufficient—dependent on and increasing with BMI; most (77.6%) disagreed with assertion that Fire Service provided sufficient diet education; Mediterranean diet is most preferred | Selection bias (self-selection, convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Non-response bias; Non-differential misclassification |

| Eastlake A et al., 2015 [6] | Cross-sectional; Hamilton County, Ohio, United States | Determine baseline for prevention on cardiovascular disease and the relation to multiple risk factors | n = 157 (out of n = 1431); Hamilton County, OH FF members; average age 40.8 (range 19–72 years old); career length unspecified; 100% male; 90.5% White, 7.6% Black/African American, 0.6% Alaskan Native/American Indian, 1.3% Other | 15-question questionnaire targeting occupational risk factors, lifestyle risk factors, and demographic characteristics. | 83% of participants consumed red meat 1–5 times/week; 90% ate fast food 1–3 times/week; 57% ate fish <1/week; 73% ate vegetables 1–5/week; 92% ate grains 1–7/week; reduced risk for high cholesterol associated with increase alcohol consumption; consumption of whole grains is major variable in predicting reduced chance of CVD. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Sotos-Prieto M et al., 2019 [18] | Cross-sectional; United States | Identify hindrances, challenges, and cost vs. time vs. social relation to food | Interviews: n = 12; source population all U.S.; mean age 49.2 ± 8.0 years; 19.4 ± 11.6 years career length; 91.7% male; 91.7% White, 8.3% Hispanic/Latino Focus Groups: n = 5; source population all U.S; mean age 50.8 ± 6.1 years; 19.4 ± 11.4 years career length; 100% male; 100% White | ~30 min. interviews about current food environment, barriers, and solutions to improve diet and lifestyle habits; ~1 h focus group meetings to talk about themes from one-on-one interviews | Fire academies and firehouses had different food environments. Most interviewees commented positively to use of Mediterranean diet. Financial resources and knowledge, as well as no supportive culture from senior staff are barriers to improving nutrition. Nutrition education, incentives, and training to promote cohesive culture of health eating were supported by interviewees. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting) |

| Haddock et al., 2015 [19] | Cross-sectional; United States | To present information on the patterns of alcohol consumption among firefighters. | n = 954 on patterns of p30 day alcohol use; n = 246 on off-duty alcohol intake from 24 hr recall; FF departments across U.S. region; 39.1 ± 8.8 years old; 14.2 ± 8.6 years career, 100% male; 76.4% White | Questionnaire modelled after common substance use questions on surveys such as the national Household Survey on Drug Abuse and on surveys of military members. | Rank was related to OR of excessive drinking and episodic heavy drinking (FF > chief); Excessive and sporadic heavy drinking are commonly related to years of service (fewest > most); years of service inversely related to # of drinks and prevalence of episodic heavy drinking on selected off-duty day. | Selection bias (voluntary participation); Information bias (recall); Differential misclassification; Non-differential misclassification |

| Yang et al., 2014 [20] | Cross-sectional; United States | Investigate effects of adherence to the Mediterranean diet and relations to CVD biomarkers, metabolic syndrome, and physical body characteristics. | n = 780; two midwestern U.S. states; 35.6 ± 10 y.o. normal weight, 372.2 ± 8.4 y.o. overweight, 38.9 ± 8 y.o. obese class I, 38.6 ± 8.1 y.o. obese class II/III; career length unspecified, 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Lifestyle questionnaire with a modified Mediterranean diet score (mMDS) on a scale of 0 (no conformity) to 42 (maximal conformity) | Obese subjects had lower mMDS; greater mMDS inversely related to risk of weight gain over past five years and presence of metabolic syndrom components; higher HDL-c and lower LDL-c in participants correlated with higher mMDS. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (recall, reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Anderson et al., 2017 [21] | Cross-sectional; United States | To determine firefighters’ perception of cancer risk | n = 100 (observation over 150 hrs), n = 17 (focus group); age in observation unspecified; focus groups age 29–58 y.o. w/average age of 51; ≥3 years career; Gender unspecified; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Interview with comment and informal questions; observations for attitude and behavior, environment, barriers, and chances for change; emerging themes used to discuss in focus groups | How healthy a meal is determined by the influence of who is cooking; constraints of occupation can play a role in diet and level of healthiness. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Observer bias |

| Chatzitheodoridis et al., 2017 [22] | Cross-sectional; Greece | To examine BMI and obesity rates among Greek firefighters and observe nutrition habits and risk factors related to obesity. | n = 190 (n = 59 normal bmi, n = 95 overweight bmi, n = 36 obese bmi); Central and Western Macedonia; 37.83 ± 6.018 y.o. normal, 39.51 ± 7.419 y.o. overweight, 43.03 ± 6.056 y.o. obese; Career length unspecified; 94.2% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | 28 questions regarding diet, exercise, and work. Questions on a 5 or 7-point Likert type scale. | Consensus that there is need for exercise/nutrition program for SFFs. Economic crisis in country has affected how grocery purchase decisions are made. | Selection bias (voluntary participation); Information bias (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Robertson et al., 2017 [23] | Cross-sectional; Canada | To assess the physiological demands and dietary habits of Canadian firefighters during operations. | n = 21 (out of n = 72 potential); northern Ontario Fire Base; 29.8 ± 8.5 y.o.; career length unspecified; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Food logs | Sufficient kilocalories for deployment not met; SFFs exceed fat intake and failed to meet recommended carbohydrate intake. Protein intake acceptable. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting) |

| Friel et al., 1988 [24] | Cross-sectional; United States | To observe if diets of FF would predispose them to risk of heart disease. | n = 35; St. John’s Fire Department; Age, career length, sex, and race/ethnicity unspecified | Food log and dietary data base | FFs on shift appear to consume more fat, cholesterol, protein, sodium, and potassium than is recommended or than they do at home; average FF in sample was classified as overweight or obese. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting) |

| Romanidou et al., 2020 [25] | Cross-sectional; United States | To examine if and what associations exist between a modified Mediterranean Diet Score and anthropometric indices, blood pressure, and biochemical parameters | n = 460; 44 Indianapolis fire stations and 6 Fishers, Indiana fire stations enrolled in Feeding America’s Bravest; 46.7 ± 8.3 y.o.; career length unspecified; 94.4% male; 85.5% White, 12.5% African American, 1.9% Other | 131-item semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire and modified Mediterranean Diet Score (a validated instrument for measuring adherence to the Mediterranean diet) | Increased adherence to the Mediterranean diet was associated with markers of lower cardiometabolic risk. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Non-response bias; Non-differential misclassification |

| Johnson & Mayer 2020 [26] | Cross-sectional; United States | To determine whether firefighters are meeting recommended guidelines of the Military Dietary Reference Intakes (MDRI) | n = 150; 13 career fire departments in Southern California enrolled in the Regional Firefighter Wellness Initiative; 37.35 ± 8.44 y.o.; career length unspecified; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Three-day food record and lifestyle questionnaire | Compared to MDRI reference values, firefighters consumed an inadequate amount of total calories, linolenic and alpha-linolenic fatty acid, fiber, vitamins D, E, and K, potassium, magnesium, zinc, and carbohydrates. Vitamin D, magnesium, and potassium had the greatest shortcomings | Selection bias (convenient sample, voluntary participation); Information bias (recall, reporting); Differential misclassification |

| Vatandoost et al., 2020 [27] | Cross-sectional; Iran | To investigate the association between dietary inflammatory index (DII) and risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD) among firefighters in Tehran | n = 273; Tehran fire stations; 33.99 ± 6.34 y.o.; career length unspecified; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | 168-item semiquantitative questionnaire | Participants with higher DII scores tend to ingest more fat, saturated fat, and less PUFA, MUFA, EPA, and DHA. Several vitamins and minerals (including A, E, K, B1, B2, B3, B6, B9, C, magnesium, zinc, and calcium) were also found to be decreased in those with higher DII scores. | Information bias (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Hershey et al., 2020 [28] | Cross-sectional; United States | To determine if there is an association between anthocyanin intake and physical activity on lipid profile measures | n = 249; Feeding America’s Bravest trial; 47.2 ± 7.4 y.o.; career length unspecified; 95% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | 131-item semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire | Anthocyanins were inversely associated with total cholesterol:high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Bonnell et al., 2017 [29] | Fixed mixed method; Australia | To explore factors influencing food choice and dietary intake in shift workers | Focus group n = 41, Dietary recall n = 19; Melbourne fire stations; 36 y.o.; career length unspecified; Focus group 97.6% male, Dietary recall 94.7% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Focus groups were conducted using semi-structured open questions and 24 hr dietary recalls via telephone interviews | Unhealthy dietary behaviors were identified among shift workers, specifically night shift that include an increase of discretionary foods and lack of availability of healthy food choices at night | Selection bias (convenient sample, voluntary participation); Information bias (recall, reporting); Differential misclassification |

| Gupta et al., 2020 [26] | Case-control; Australia | To investigate the impact of heat and sleep restriction on snacking behavior and food cravings | n = 66; Southern Australian fire stations; Control 39 ± 16 y.o., Sleep Restricted 39 ± 15 y.o., Hot 36 ± 13 y.o., Hot & Sleep Restricted 41 ± 17 y.o.; Career length unspecified; 84.8% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Food records and hunger/cravings questionnaire | Sleep restriction and heat did not impact feelings of hunger and fullness across the day and did not lead to greater cravings for snacks. These findings suggest that under various simulated firefighting conditions, it is not the amount of food that differs but the timing of food intake. | Selection bias (controls selection); Information (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Hershey et al., 2021 [30] | Cross-sectional; United States | To assess the association between the Mediterranean lifestyle and metabolic syndrome | n = 249; Feeding America’s Bravest trial; Age (1st Tertile 46.92 ± 6.98 y.o., 2nd Tertile 46.66 ± 7.57 y.o., 3rd Tertile 46.56 ± 8.08 y.o.); Career length unspecified; Sex (1st Tertile 97.8% male, 2nd Tertile 92.9% male, 3rd Tertile 93.3% male); Race/ethnicity unspecified | 131- item semi-quantitative 2007 grid Harvard food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ), also known as the Willett FFQ | Higher adherence to traditional Mediterranean lifestyle habits, as measured by a comprehensive MEDLIFE index, was associated with a lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome and a more favorable cardiometabolic profile. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (recall, reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Kadiwar et al., 2021 [31] | Cross-sectional; United States | To characterize the diet of volunteer firefighters compared with the United States recommended dietary intake | n = 122; New Jersey Firefighter Cancer Assessment and Prevention Study (CAPS); Age (17.9% < 30 y.o., 29.5% 30–39.9 y.o., 24.1% 40–49.9 y.o., 28.6% ≥ 50 y.o.); Career length (25% < 10 yeas., 25.9% 10–≤25 yeas, 26.8% 25–≤40 yeas., 22.3% ≥ 40 yeas.); 100% male; 96.4% non-Hispanic white | Dietary Screener Questionnaire | Participants had lower mean intakes of fruit and vegetables, whole grains, and dietary fiber, and a higher mean intake of added sugars compared with the U.S. recommended dietary intake. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Non-differential misclassification |

| Author/Year | Study Design, Study Location | Study Objective | Study Population [Sample Size, Age, Career Length, Sex, Race/Ethnicity] | Type and Length of Intervention | Outcome (If Any) | Key Results | Qualitative Narrative Assessment of Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Waldman HS et al., 2019 [32] | Cross-over; United States | Effect of 28-day carbohydrate restricted diet on performance and cardiometabolic markers | n = 15 (from 21 initial persons); 33.5 ± 9.7 years; 7.9 ± 7.4 years; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Carbohydrate restricted; 28 days | Cardiometabolic and performance parameters | Average body weight reduced by 2.7 kg; respiratory exchange rate reduced; SBP and DBP reduced; rating of perceived exertion reduced | Selection bias (convenient sample, small sample); Information bias (reporting); Carryover effects; Differential misclassification |

| Sotos-Prieto et al., 2017 [7] | Cluster-randomized intervention; United States | Change fire departments’ food culture; Compare Mediterranean Diet Nutritional Intervention (MDNI) (group 1) vs. usual care (group 2; control) and its outcomes. | n = 1000 (from 44 fire stations), 18 years old or older, all career firefighters (no length listed), 95% Male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Applied the Mediterranean diet at work and at home for 12 months; In Phase II of the remaining 12 months, group 1 no longer received active MDNI and continued a self-sustained continuation, while group 2 crossed over to receive six months of active MDNI and six months of self-sustained continuation. | None | Increase knowledge; increase self-efficacy; normalized healthy behaviors; navigate barriers to discounted food access | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (recall, reporting); Carryover effects; Noncompliance/Loss to follow-up |

| Ranby et al., 2011 [33] | Balanced randomized trial; United States | Examine the process where PHLAME improved healthy eating and physical activity among firefighters | n = 397 (from 48 stations), mean age of 41 years old, no career length provided, 93% Male; 91% White | Health Promotion Intervention, 12-month intervention with 1 year follow-up | Increase knowledge and self-efficacy about fruit/vegetable consumption and exercise compared to controlled PPTs. | Team participants post-intervention had increased fruit/vegetable consumption; increased knowledge of health benefits from fruit/vegetable consumption; improved dietary environment among coworkers. | Selection bias (convenient sample, control selection, non-independent samples); Information bias (recall, reporting); Loss to follow-up; Exposure misclassification |

| Elliot et al., 2007 [34] | Randomized trial; United States | Assess and compare PHLAME’s (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models’ Effects) two health promotion methods | n = 599; 41 ± 9 years; 16± 9 years; 579 men (97%) and 20 women; 91% White | The PHLAME study compared (1) a team-based curriculum, (2) motivational interviewing that is one-on-one. Used social cognitive theory components as well; 12 months | Fruit and vegetable consumption, daily physical activity, and adequate body weights. | Increased fruit and vegetable consumption among team and MI; increased general well-being; significantly less weight gain. | Selection bias (convenient sample, non-independent samples); Information bias (recall, reporting); Loss to follow-up; Exposure misclassification |

| Gill et al., 2019 [35] | Cluster-randomized controlled clinical trial; United States | Test the feasibility of a lifestyle intervention aimed to improve risks associated with CVD. | n= 96 for treatment, n = 79 for control; treatment 43.02 ± 8.25 years and control 41.77 ± 9.68 years; no career length listed; treatment 89.58% male and control 97.46% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Personalized diet and exercise plan; 12 months | HDL level measurements; physical and biological characteristics of the body, e.g., weight, body fat, circumference of waist/hip, glycemic level, insulin resistance. | Significant reduction of body weight and waist circumference; Increased a1 HDL; Decreased triglyceride and insulin concentrations; Program adherence with weight loss and increases in ⍺1HDL | Selection bias (control selection); Information bias (recall, reporting) |

| Macedo et al., 2015 [36] | Randomized trial (controlled double-blinded); Brazil | Determine the plasma metabolic response and oxidative stress indicators in Brazilian military firefighters | n = 60; Placebo 22.3 ± 1.78 years treatment 21.46 ± 1.77 years; no career length listed; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Resveratrol (RES) supplementation; 90 days | RES supplements did not induce any changes regarding hepatic consequences. | IL-6 and TNF-a levels reduced after three months of RES supplements. Physical fitness test did not challenge antioxidant defense system, so no tangible results. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Exposure misclassification |

| McDonough SL et al., 2015 [37] | Cohort intervention; United States | (1) To determine the feasibility of an 8-week wellness program; (2) To test the effect of “FIT Firefighter” intervention on cardiovascular fitness. | n= 29; 38.6 ± 5.5 years; no career length (just said they were all fulltime); Sex and race/ethnicity unspecified | Nutrition education, health coaching, and strength and fitness condition; 8-weeks | Changes in physical characteristics of the body, i.e., BP, resting HR, aerobic fitness, circumference of waist, body weight. | Improved behavior changes regarding health and nutrition. Improvement in physical characteristics. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting); Exposure misclassification |

| Pirlott et al., 2012 [38] | Randomized trial; United States | Report findings to understand the nuances of how an MI counselor speaks during the PHLAME intervention. | n = 202; 41 ± 7.46 years; no career length listed; 98% male; 95% White | Randomized prospective worksite trial; 12 months | Daily fruit and vegetable consumption. | Increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. MI Counselor empathy and consistent behavior indicates better influence on SFF’s increased consumption of fruits and vegetables | Selection bias (convenient sample, non-independent samples); Information bias (recall, reporting); Exposure misclassification |

| Goheer A. et al., 2014 [39] | Cohort Study; United States | Create, introduce, and evaluate nutrition intervention to reduce adverse health risks among firefighters. | n = 90; Age, career length, sex, and race/ethnicity unspecified | Intervention contained education sessions (written and visual) to demonstrate healthier nutrition; 6 months with a 1-year follow up | No outcomes listed | Majority report improved changes in food environment at firehouse and personal home. Education sessions and demonstrations were highest rated for most helpful in the intervention. | Information bias (reporting); Noncompliance |

| MacKinnon DP et al., 2010 [40] | Randomized trial; United States | Describe immediate and sustainable effects of health intervention programs for structural firefighters. | n = 599; MI = 41 ± 8.9 years, TEAM = 39.3 ±8.7 years, and control = 41.3 ± 8.8 years; MI = 16.4 ± 8.5 years, TEAM 14.4 ± 8.7, and control 15.7 ± 8.9; 579 men (97%) and 20 women; 91% White | (a) A team-based, peer-led scripted health promotion curriculum, (b) one-on-one motivational interviewing health coaching, and (c) a testing-and-results-only comparison condition; baseline, 2 intervention years, and 4 follow-up years | Intervention behavioral objectives: (1) minimum consumption of 5 servings of fruits and vegetables, (2) being physically active for minimum 30 min a day, (3) maintaining a healthy body weight | High willingness to try new food and preparation at the firehouse and personal home. Team-based curriculum more effective on nutritional behavior and physical fitness at one year follow-up compared to one-on-one MI. | Selection bias (convenient sample, non-independent samples); Information bias (reporting); Loss to follow-up; Exposure misclassification |

| Day et al., 2019 [41] | Randomized control trial with crossover; United States | Evaluate efficacy of tailored weight loss intervention among volunteer firefighters. | Treatment n = 217; Control n = 178; VFF all over U.S.; treatment age 37.3 ± 12.7, control age 36.9 ± 12.6; career length for treatment 10.5 ± 9.9, control 11.0 ± 10.0; treatment 77.5% male, control 83.6% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | A web-based health and wellness program called “The First Twenty”; contains online nutrition education, recommendations for physical activity, and encourages mental health applications; 12 months | Weight loss | Participants experienced 1.7–2.8 pounds of weight loss after the intervention concluded. There is still a need to improve adherence to program. | Selection bias (control selection); Information bias (reporting); Carryover effects; Exposure misclassification |

| Sotos-Prieto M et al., 2019 [42] | Cohort (nested); United States | To determine the validity of mMDS vs. biomarkers and FFQ for determining Mediterranean diet practice | n = 48; 24 on self-sustained Mediterranean diet after 12-month education intervention; 24 on active education intervention after 12 months of no intervention; Indianapolis FD; 47.52 ± 7.63 years (48.36 ± 8.29 years in parent study); 92.7% male; 82.8% White, 7.2% African American, 3.2% Other | 13-domain Modified Mediterranean Diet Scale (mMDS), FFQ-derived mMDS, FFQ after 12 months | Assessing the concordance between questionnaires and adherence to Mediterranean Diet. | mMDS items (olive oil intake, choice of olive oil as type of fat, overall mMDS score) correlated with omega-3 PUFA; FFQ nutrient intake correlated with DHA and EPA at baseline and at follow-up (r = 0.624–0.775) | Selection bias (convenient sample, non-independent sample); Information bias (recall, reporting); Noncompliance/Loss to follow-up; Exposure misclassification |

| Sotos-Prieto et al., 2020 [43] | Cluster-randomized controlled trial (nested); United States | To investigate the longitudinal effects of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic biomarkers | Group 1 Int. n = 24, Group 1 Cont. n = 24, Group 2 Int. n = 22, Group 2 Cont. n = 22; Feeding America’s Bravest trial; Group 1 Int. 47.5 ± 6.7 y.o., Group 1 Cont. 47.6 ± 8.6 y.o., Group 2 Int. 45.9 ± 6.7 y.o., Group 2 Cont. 49.9 ± 8.4 y.o.; Career length not specified; Group 1 Int. 91.7% male, Group 1 Cont. 95.8% male, Group 2 Int. 84.6% male, Group 2 Cont. 94.1% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Mediterranean Diet Intervention (MedDiet intervention) consisting of educational sessions and videos, leaflet and recommendations, firefighter-tailored Mediterranean, in-site chef cooking demonstration, a firefighters’ food pyramid, Mediterranean food samples and discount coupons to a large supermarket chain for specific Mediterranean Diet-compatible foods. 12 months | Analysis of plasma metabolic biomarkers, assessment of adherence to Mediterranean diet via the Mediterranean Diet Score and PREDIMED score | The MedDiet intervention led to favorable changes in biomarkers related to lipid metabolism, including lower LDL-C, ApoB/ApoA1 ratio, remnant cholesterol, M-VLDL-CE; and higher HDL-C, and better lipoprotein composition. | Selection bias (convenient sample, non-independent sample); Non-differential misclassification; Differential misclassification; Noncompliance/Loss to follow-up |

| Ng et al., 2021 [44] | Cluster randomized controlled trial; Hong Kong | To explore the feasibility of a promotion pamphlet and/or WhatsApp as a suitable mode of delivery to promote healthy eating habits with fruit and vegetables | Int. group n = 20, control group n = 25); 23 fire stations in Hong Kong; Age 35.0 ± 9.6 y.o. (int. group 32.9 ± 9.5 y.o., control group 36.6 ± 9.6 y.o.); Career Experience 11.3 ± 9.9 yeas (Intervention 9.4 ± 9.6 yeas, Control 12.8 ± 10.1 yeas); 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Health promotion pamphlet and teaching materials through WhatsApp; 8 weeks | Assessment of eating habits, specifically fruits and vegetables, as well as retention, practicality, and implementation of the intervention | There were significant improvements in the mean numbers of days consuming fruits and vegetables in the intervention group, and for fruit consumption in the control group. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (recall, reporting); Noncompliance/Loss to follow-up |

| Almeida et al., 2022 [45] | Two-group (Firefighters v. Civilians) diet and exercise pre-post intervention; United States | To examine the relationship between diet adherence and cardiovascular disease risk-reduction between civilians and firefighters with a 6-week Mediterranean diet and tactical training intervention | Firefighters n = 40, Civilians n = 30; Age (Civilians 41.6 ± 15.8 y.o.; Firefighters 39.6 ± 14.7 y.o.); Career length mean 18.8 years; Sex (Civilians 36.7% male, Firefighters 92.5% male); Race/ethnicity unspecified | Training session explaining the modified Mediterranean diet, diet manual, sample tracking sheets, sample recipes, and information on types of foods, access to a study website, and a ‘health coach’. 6 weeks | No outcomes specified | Both groups had improvements in blood pressure and body composition. However, the civilian group overall had better adherence to the diet. | Selection bias (convenient sample); Information bias (reporting) |

| Bucher et al., 2019 [46] | Pre- and post-intervention design; Switzerland | To assess the eating habits of firefighters, compare them with national guidelines, and evaluate the impact of this prevention program | n = 28; Swiss airport firefighters; Age 40.2 ± 6.3 y.o.; Career length 17.0 ± 6.3 y.o.; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | 1 h educational workshop and a cooking class, as well as 1 h of individual coaching from a dietitian; 1 year | Assessment of anthropometric measurements | Intervention did not impact eating habits or anthropometrics at the group level. Main reported barriers for healthy eating were lack of motivation, prioritization, or time. | Selection bias (convenient sample, small sample); Information bias (reporting); Differential misclassification |

| Waldman et al., 2020 [47] | Cross-over; United States | To examine the effects of a 28-day, nonketogenic, carbohydrate-restricted diet on markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and heart disease, using the AHA guidelines for risk stratification in professional firefighters | n = 15; Mean age not specified but age range was 20–45 y.o.; Career length not specified; 100% male; Race/ethnicity unspecified | Intervention was a nonketogenic, carbohydrate-restricted diet. 28 days | Anthropometric measurements; blood analysis; assessment of macronutrient breakdowns | Compared with baseline, the carbohydrate-restricted diet resulted in dramatic improvements to subjects’ cardiometabolic profiles. | Selection bias (convenient sample, small sample); Information bias (reporting); Carryover effects; Differential misclassification |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joe, M.J.; Hatsu, I.E.; Tefft, A.; Mok, S.; Adetona, O. Dietary Behavior and Diet Interventions among Structural Firefighters: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214662

Joe MJ, Hatsu IE, Tefft A, Mok S, Adetona O. Dietary Behavior and Diet Interventions among Structural Firefighters: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2022; 14(21):4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214662

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoe, Margaux J., Irene E. Hatsu, Ally Tefft, Sarah Mok, and Olorunfemi Adetona. 2022. "Dietary Behavior and Diet Interventions among Structural Firefighters: A Narrative Review" Nutrients 14, no. 21: 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214662

APA StyleJoe, M. J., Hatsu, I. E., Tefft, A., Mok, S., & Adetona, O. (2022). Dietary Behavior and Diet Interventions among Structural Firefighters: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 14(21), 4662. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214662