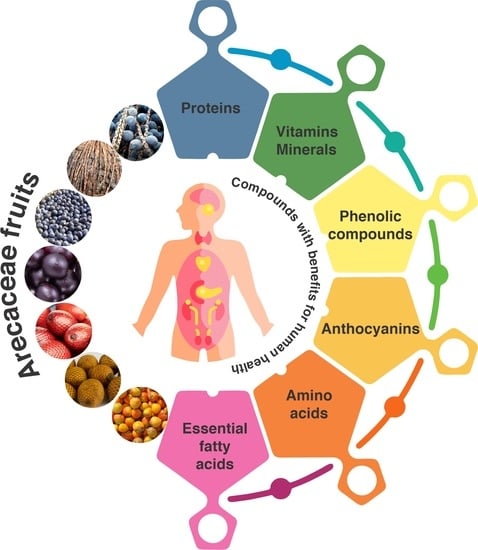

Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Native Brazilian Fruits of the Arecaceae Family and Its Potential Applications for Health Promotion

Abstract

1. Introduction

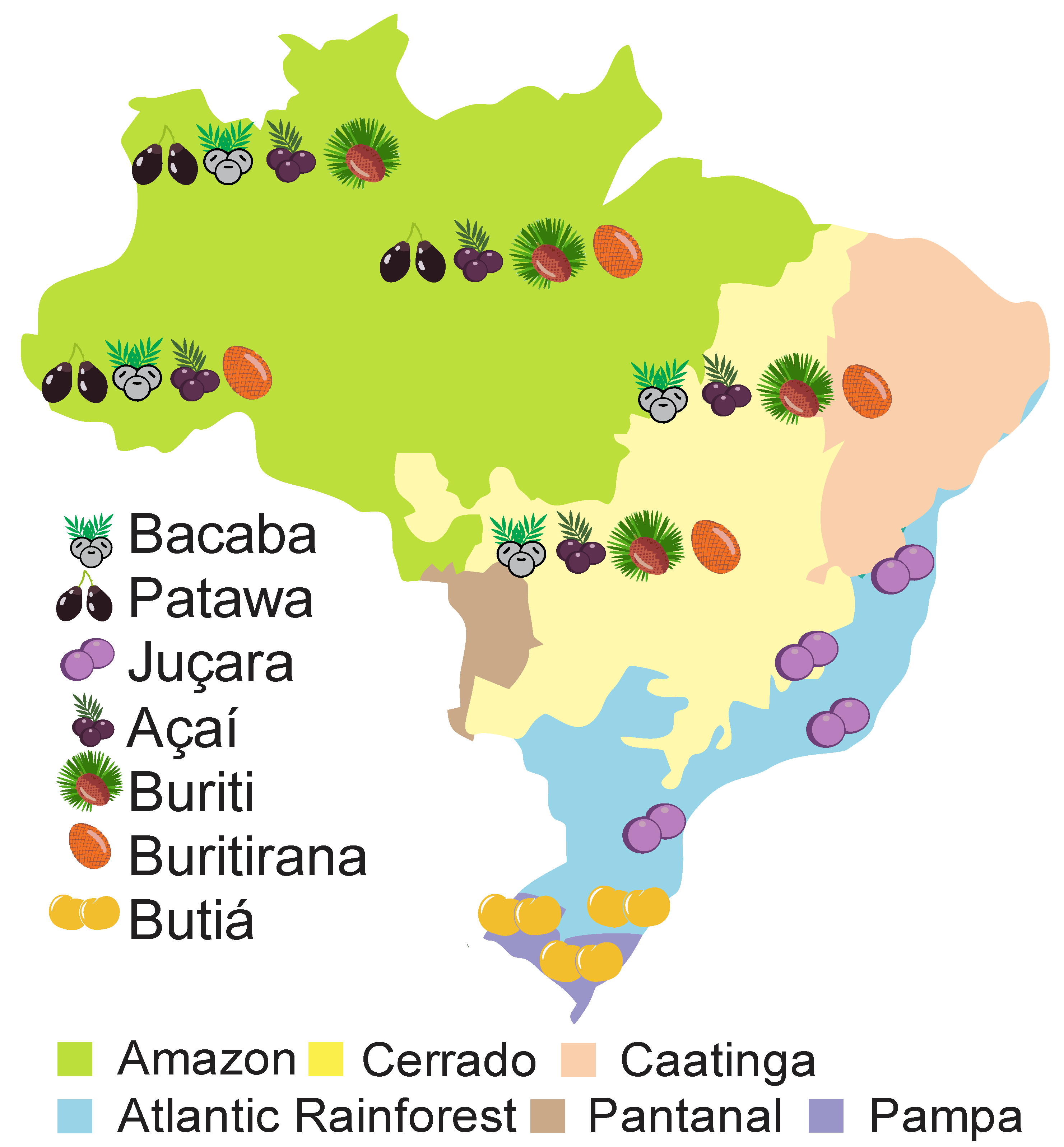

2. Ethnobotanical Characteristics

2.1. Bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba Mart.)

2.2. Patawa (Oenocarpus bataua Mart.)

2.3. Juçara (Euterpe edulis Mart.)

2.4. Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.)

2.5. Buriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.f.)

2.6. Buritirana (Mauritiella armata Mart.)

2.7. Butiá (Butia odorata (Barb. Rodr.) Noblick)

3. Macro and Micronutrients

3.1. Lipid Profile

3.2. Amino Acids

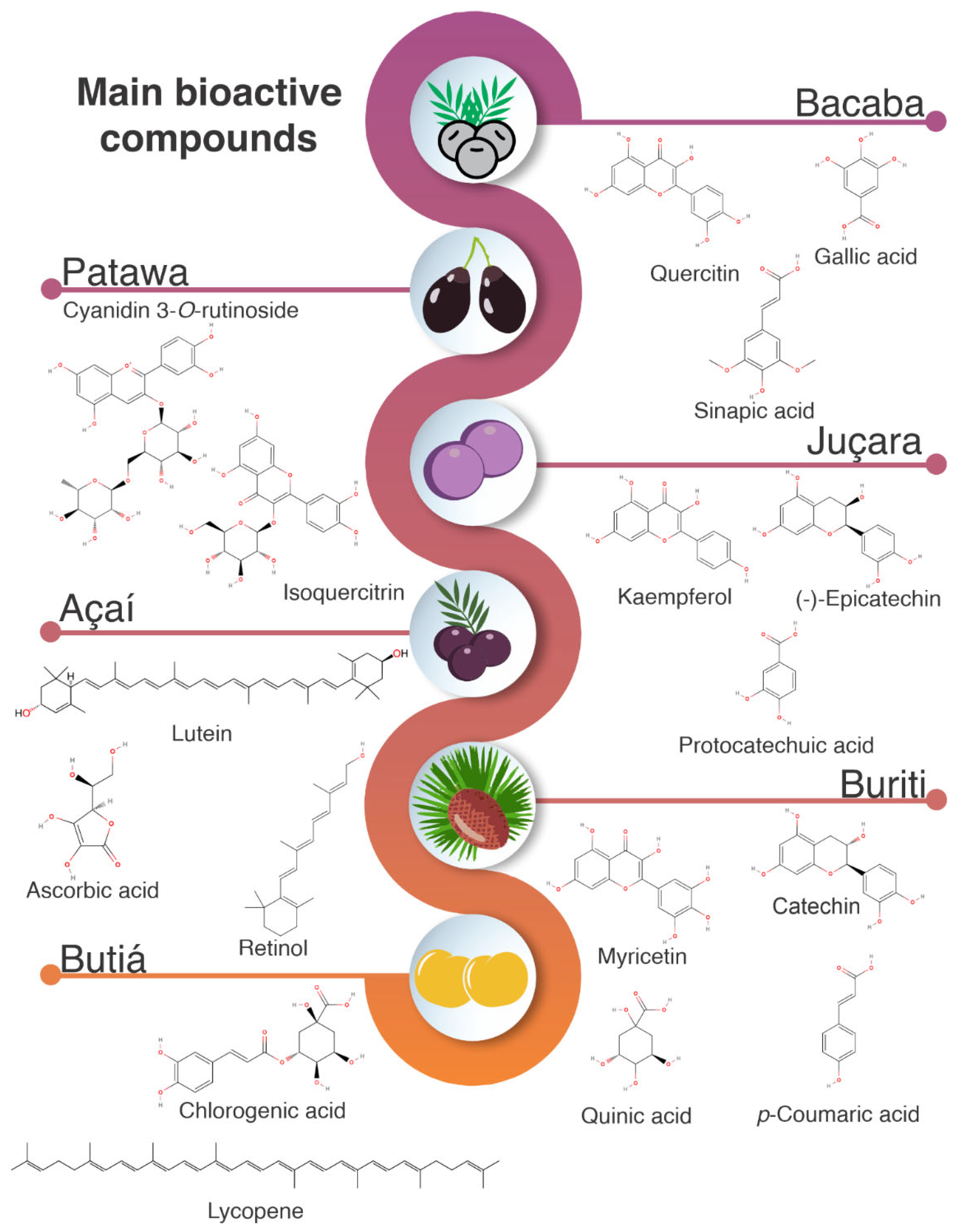

4. Bioactive Compounds

4.1. Phenolic Compounds

4.2. Anthocyanins

4.3. Carotenoids and Vitamin C

5. Biological Effects and Potential Health Benefits of Phenolic Compounds

5.1. Antioxidant Activity

5.2. Antimicrobial Effects

5.3. Anti-Inflammatory and Hypocholesterolemic Effect

5.4. Antitumoral/Antiproliferative Activity and Other Effects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Valli, M.; Russo, H.M.; Bolzani, V.S. The potential contribution of natural products from Brazilian biodiversity to the bioeconomy. Ann. Braz. Acad. Sci. 2018, 90, 763–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, D.C.D.; Oliveira Filho, J.G.D.; Sousa, T.L.D.; Ribeiro, C.B.; Egea, M.B. Ameliorating effects of metabolic syndrome with the consumption of rich-bioactive compounds fruits from Brazilian Cerrado: A narrative review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1, 7632–7649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBIF. Global Biodiversity Information Facility Secretariat. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/species/7681 (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- Teixeira, G.L.; Ibañez, E.; Block, J.M. Emerging Lipids from Arecaceae Palm Fruits in Brazil. Molecules 2022, 27, 4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, O.V.; Langley, A.C.D.C.P.; Lima, A.J.M.; Moraes, V.S.V.; Soares, S.D.; Teixeira-Costa, B.E. Nutraceutical potential of Amazonian oilseeds in modulating the immune system against COVID-19–A narrative review. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 1, 105123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.G.; Araújo, F.F.; Paulo Farias, D.; Zanotto, A.W.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Pastore, G.M. Brazilian fruits of Arecaceae family: An overview of some representatives with promising food, therapeutic and industrial applications. Food Res. Int. 2020, 1, 109690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speranza, P.; Alves, J.; Macedo, A. Amazonian Buriti oil: Chemical characterization and antioxidant potential. Grasas Y Aceites 2016, 67, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A.L.; Liz, S.; Rieger, D.K.; Farah, A.C.A.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Assis, M.A.A.; Di Pietro, P.F. An update on the biological activities of Euterpe edulis (Juçara). Planta Med. 2018, 50, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, B.M.; Baldissera, L.; Barbosa, F.R.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Andrighetti, C.R.; Silva Agostini, J.; Sousa Valladao, D.M. Centesimal and mineral composition and antioxidant activity of the bacaba fruit peel. Biosci. J. 2019, 35, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, V.D.Y.; Solas, S.Á.; Peñuela, M.C. The palm Mauritia flexuosa, a keystone plant resource on multiple fronts. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.R.; Júnior, R.N.C. Food sustainability trends-How to value the açaí production chain for the development of food inputs from its main bioactive ingredients? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 1, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CONAB. Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento; Boletim da Sociobiodiversidade/Companhia Nacional de Abastecimento: Brasília, Brazil, 2020; Volume 1, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, L.A.O.P.; Souza, R.G. Palmeira Juçara: Patrimônio Natural da Mata Atlântica no Espírito Santo; INCAPER: Vitória, Brazil, 2017; Volume 1, ISBN 978-85-89274-27-2. [Google Scholar]

- Copetti, C.L.K.; Orssatto, L.B.; Diefenthaeler, F.; Silveira, T.T.; Silva, E.L.; Liz, S.; Di Pietro, P.F. Acute effect of juçara juice (Euterpe edulis Martius) on oxidative stress biomarkers and fatigue in a high-intensity interval training session: A single-blind cross-over randomized study. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 67, 103835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, J.S.; Barizão, É.O.; Rotta, E.M.; Volpato, H.; Nakamura, C.V.; Maldaner, L.; Visentainer, J.V. Phenolic compounds from Butia odorata (Barb. Rodr.) noblick fruit and its antioxidant and antitumor activities. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.M.M.A.; Passos, T.S.; Cruz Nascimento, S.S.; Medeiros, I.; Araújo, N.K.; Maciel, B.L.L.; Assis, C.F. Gelatin nanoparticles enable water dispersibility and potentialize the antimicrobial activity of Buriti (Mauritia flexuosa) oil. BMC Biotechnol. 2020, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakmal, K.; Yasawardene, P.; Jayarajah, U.; Seneviratne, S.L. Nutritional and medicinal properties of Star fruit (Averrhoa carambola): A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 1810–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonato, C.D.F.A.; Leite, D.O.D.; Pereira, R.C.; Boligon, A.A.; Ribeiro-Filho, J.; Rodrigues, F.F.G.; Costa, J.G.M. Chemical analysis and evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fruit fractions of Mauritia flexuosa L. f. (Arecaceae). PeerJ 2018, 6, e5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoda, H.; Takeda, S.; Takarada, T.; Kato, Y.; Shimizu, N.; Toda, K.; Matsuda, H. Hydroxypterocarpans with estrogenic activity in Aguaje, the fruit of Mauritia flexuosa (Peruvian moriche palm). Bioact. Compd. Health Dis. 2019, 2, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N.; Melo, J.C.; Batista, L.F.; Paula-Souza, J.; Fronza, P.; Brandao, M.G. Edible fruits from Brazilian biodiversity: A review on their sensorial characteristics versus bioactivity as tool to select research. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, F.F.; Neri-Numa, I.A.; Paulo Farias, D.; Cunha, G.R.M.C.; Pastore, G.M. Wild Brazilian species of Eugenia genera (Myrtaceae) as an innovation hotspot for food and pharmacological purposes. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, E.; Soares-Filho, B.; Souza, F.; Rajão, R.; Merry, F.; Ribeiro, S.C. Mapping the socio-ecology of Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFP) extraction in the Brazilian Amazon: The case of açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart) in Acre. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 188, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, P.B. Frutas Comestíveis na Amazonia, 7th ed.; CNPq/Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi: Belém, Brazil, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 1–279. [Google Scholar]

- Lauvai, J.; Schumacher, M.; Finco, F.D.B.A.; Graeve, L. Bacaba phenolic extract attenuates adipogenesis by down-regulating PPARγ and C/EBPα in 3T3-L1 cells. NFS J. 2017, 9, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, F.A. Health Enhancing Traditional Foods in Brazil: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Food and Nutritional Security; Informations-und Medienzentrum der Universität Hohenheim: Hohenheim, Alemanha, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cól, C.D.; Tischer, B.; Flôres, S.H.; Rech, R. Foam-mat drying of bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba): Process characterization, physicochemical properties, and antioxidant activity. Food Bioprod. Process. 2021, 126, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.A.D.; Andrade, E.L.; Santana, E.B.; Ribeiro, N.F.D.P.; Costa, C.M.L.; Faria, L.J.G.D. Bacaba powder produced in spouted bed: An alternative source of bioactive compounds and energy food product. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22, e2018229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, C.R.D.; Oliveira, M.N.D.; Souza Filho, M.F.D.; Silva, R.A.D.; Zucchi, R.A. First record of Anastrepha parishi Stone (Diptera, Tephritidae) and its host in Brazil. Rev. Bras. De Entomol. 2008, 52, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, F.R.F.; Sesquim, E.A.R.; Raasch, G.S.; Cíntra, D.E. Característica físico-química e perfil lipídico da bacaba proveniente da Amazônia ocidental. Braz. J. Food Res. 2016, 7, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seixas, F.R.F.; Vieira, T.S.; Cintra, D.E.C. Caracterização físico-química e da fração lipídica do patauá proveniente da aldeia baixa verde no município de Alto Alegre dos Parecis-RO. Rev. Científica Da Unesc. 2016, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, A.; Galeano, G.; Bernal, R. Field Guide to the Palms of the Americas; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, P.S.; Rita de Cássia, S.N.; Nunomura, S.M. Plantas oleaginosas amazônicas: Química e atividade antioxidante de patauá (Oenocarpus bataua Mart.). Rev. Virtual De Química 2016, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogez, H. Açaí: Preparo, Composição e Melhoramento da Conservação; EDUPA: Belém, Brazil, 2000; Volume 1, p. 360. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M.; Borges, G.D.S.C.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Juçara fruit (Euterpe edulis Mart.): Sustainable exploitation of a source of bioactive compounds. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, H.; Noblick, L.; Kahn, F.; Ferreira, E. Flora Brasileira—Arecaceae (Palmeiras); Plantarum: Nova Odessa, Brazil, 2010; Volume 1, p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, G.D.S.C.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Copetti, C.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Zambiazi, R.C.; Mancini Filho, J.; Fett, R. Chemical characterization, bioactive compounds, and antioxidant capacity of jussara (Euterpe edulis) fruit from the Atlantic Forest in southern Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2128–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicudo, M.O.P.; Ribani, R.H. Anthocyanins and Antioxidant Properties of Juçara Fruits (Euterpe edulis M.) Along the On-tree Ripening Process. Blucher Biochem. Proc. 2015, 1, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bicudo, M.O.P.; Ribani, R.H.; Beta, T. Anthocyanins, phenolic acids and antioxidant properties of juçara fruits (Euterpe edulis M.) along the on-tree ripening process. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2014, 69, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmann, G.; Reis, T.; Goudel, F.; Miller, P.R.M.; Silva, E.; Block, J.M. Frutos da palmeira-juçara: Alimento de qualidade para os catarinenses. Agropecuária Catarin 2013, 26, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M.; Seraglio, S.K.T.; Brugnerotto, P.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Costa, A.C.O.; Fett, R. Composition and potential health effects of dark-colored underutilized Brazilian fruits–A review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.K.L.; Pereira, L.F.R.; Lamarão, C.V.; Lima, E.S.; Veiga-Junior, V.F. Amazon açaí: Chemistry and biological activities: A review. Food Chem. 2015, 179, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strudwick, J.; Sobel, G. Uses of Euterpe oleracea Mart. in the Amazon Estuary, Brazil. Adv. Econ. Bot. 1988, 6, 225–253. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43927532 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Torma, P.D.C.M.R.; Brasil, A.V.S.; Carvalho, A.V.; Jablonski, A.; Rabelo, T.K.; Moreira, J.C.F.; Oliveira Rios, A. Hydroethanolic extracts from different genotypes of açaí (Euterpe oleracea) presented antioxidant potential and protected human neuron-like cells (SH-SY5Y). Food Chem. 2017, 222, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.P.; Cunha, V.M.B.; Sousa, S.H.B.; Menezes, E.G.O.; Bezerra, P.N.; Neto, J.T.F.; Junior, R.N.C. Supercritical CO2 extraction of lyophilized Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp oil from three municipalities in the state of Pará, Brazil. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 31, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichara, C.M.G.; Rogez, H. Açai (Euterpe oleracea Martius). In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.D.S.P.; Neto, J.T.F.; Pena, R.S. Açaí: Técnicas de cultivo e processamento. CEP 2007, 60, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Jesus, A.L.T.; Cristianini, M.; Santos, N.M.; Júnior, M.R.M. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on the microbial inactivation and extraction of bioactive compounds from açaí (Euterpe oleracea Martius) pulp. Food Res. Int. 2020, 130, 108856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, A.L.T.; Leite, T.S.; Cristianini, M. High isostatic pressure and thermal processing of açaí fruit (Euterpe oleracea Martius): Effect on pulp color and inactivation of peroxidase and polyphenol oxidase. Food Res. Int. 2018, 105, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.N.; Claro, P.I.; Freitas, R.R.; Martins, M.A.; Souza, T.M.; Silva, B.M.; Bufalino, L. Enhancement of the Amazonian Açaí Waste Fibers through Variations of Alkali Pretreatment Parameters. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16, e1900275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Tabela 5457—Área Plantada ou Destinada à Colheita, área Colhida, Quantidade Produzida, Rendimento Médio e Valor da Produção das Lavouras Temporárias e Permanentes. In Sist. IBGE Recuper. 2021. Available online: https://sidra.ibge.gov.br/tabela/5457 (accessed on 5 July 2022).

- Reis, A.F.; Schmiele, M. Características e potencialidades dos frutos do Cerrado na indústria de alimentos. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2019, 22, e2017150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.S.; Ribeiro, L.M.; Mercadante-Simões, M.O.; Nunes, Y.R.F.; Lopes, P.S.N. Seed structure and germination in buriti (Mauritia flexuosa), the Swamp palm. Flora-Morphol. Distrib. Funct. Ecol. Plants 2014, 209, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, T.B.; Mello Carneiro, J.G. Frutos e polpa desidratada buriti, Mauritia flexuosa L.: Aspectos físicos, químicos e tecnológicos. Rev. Verde De Agroecol. E Desenvolv. Sustentável 2011, 6, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, I.R.; Oliveira, J.S.; Santos, K.P.; Silva, G.O.; Vieira, F.J.; Barros, R.F. A contingent valuation study of buriti (Mauritia flexuosa Lf) in the main region of production in Brazil: Is environmental conservation a collective responsibility? Acta Bot. Bras. 2016, 30, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.C.; Filgueiras, T.D.S.; Albuquerque, U.P. Use and diversity of palm (Arecaceae) resources in central western Brazil. Sci. World J. 2014, 1, e94204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, D.D.O.; Xisto, A.L.R.P.; Rodrigues, E.C.; Morais, E.C.D.; Barros, W.M.D. Antioxidant activity and physicochemical characteristics of buriti pulp (Mauritia flexuosa) collected in the city of Diamantino–MTS. Rev. Bras. De Frutic. 2017, 39, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhães, L.; Menezes, E.; Marques, A.; Sabaa Srur, A. Flavored buriti oil (Mauritia flexuosa, Mart.) for culinary usage: Innovation, production and nutrition value. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolen, H.H.; Silva, F.M.; Silva, V.S.; Paz, W.H.; Bataglion, G.A. Buriti fruit—Mauritia flexuosa. In Exotic Fruits; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Palms and People in the Amazon; Springer International Publishing: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Anunciação, P.C.; Giuffrida, D.; Murador, D.C.; Filho, G.X.P.; Dugo, G.; Pinheiro-Sant’Ana, H.M. Identification and quantification of the native carotenoid composition in fruits from the Brazilian Amazon by HPLC–DAD–APCI/MS. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2019, 83, 103296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, F.G.; Araújo, F.F.; Orlando, E.A.; Rodrigues, F.M.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Pallone, J.A.L.; Pastore, G.M. Characterization of Buritirana (Mauritiella armata) Fruits from the Brazilian Cerrado: Biometric and Physicochemical Attributes, Chemical Composition and Antioxidant and Antibacterial Potential. Foods 2022, 11, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitz, R. Flora ilustrada catarinense. Plantas Fascic Calyceraceas 1988, 18, 1–128. [Google Scholar]

- Geymonat, G.; Rocha, N. M´botia, Ecosistema Único en el Mundo; Casa Ambiental: Castillos, Uruguay, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 1–405. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, R.C.D.; Lopes, P.S.N.; Junior, D.D.S.B.; Gomes, J.G.; Pereira, M.B. Fruit and seed biometry of Butia odorata (Mart.) Beccari (Arecaceae), in the natural vegetation of the North of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Biota Neotrop. 2010, 10, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.; Jaurena, M.; Gutiérrez, L.; Barbieri, R.L. Diversidade vegetal do campo natural de Butia odorata (Barb. Rodr.) Noblick no Uruguai. Agrociencia Urug. 2014, 18, 14–27. [Google Scholar]

- Marchi, M.M.; Barbieri, R.L.; Sallés, J.M.; Costa, F.A.D. Flora herbácea e subarbustiva associada a um ecossistema de butiazal no Bioma Pampa. Rodriguésia 2018, 69, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, H.; Souza, H.M.; Costa, J.T.M.; Cerqueira, L.S.C.; Ferreira, E. Palmeiras brasileiras e exóticas cultivadas. Nova Odessa Inst. Plant. 2004, 1, 1–416. [Google Scholar]

- Má, C.; Dunshea, F.R.; Suleria, H.A. Lc-esi-qtof/ms characterization of phenolic compounds in palm fruits (jelly and fishtail palm) and their potential antioxidant activities. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, L.; Castellani, T.T.; Reis, A. Reproductive biology of Butia capitata (Martius) Beccari var. odorata in coastal sandy shrub vegetation in Laguna, SC. Rev. Bras. De Botânica 1998, 21, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, E.; Fachinello, J.C.; Barbieri, R.L.; Silva, J.B.D. Avaliação de populações de Butia capitata de Santa Vitória do Palmar. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura. Rev. Bras. De Frutic. 2010, 32, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.F.; Zandoná, G.P.; Santos, P.S.; Dallmann, C.M.; Madruga, F.B.; Rombaldi, C.V.; Chaves, F.C. Stability of bioactive compounds in butiá (Butia odorata) fruit pulp and nectar. Food Chem. 2017, 237, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Tejada-Ortigoza, V.; Heredia-Olea, E.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Welti-Chanes, J. Differences in the dietary fiber content of fruits and their by-products quantified by conventional and integrated AOAC official methodologies. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2018, 67, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, A.M.; Champ, M.M.J.; Cloran, S.J.; Fleith, M.; Lieshout, L.V.; Mejborn, H.; Burley, V.J. Dietary fibre in Europe: Current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes and relationships to health. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 149–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnet, S.H.; Silva, L.H.M.D.; Rodrigues, A.M.D.C.; Lins, R.T. Nutritional composition, fatty acid and tocopherol contents of buriti (Mauritia flexuosa) and patawa (Oenocarpus bataua) fruit pulp from the Amazon region. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 31, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, H.L.; Campbell, B.J. Dietary fibre—Microbiota interactions. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damasceno, N.R.T.; Vila, A.S.; Cofán, M.; Heras, A.M.P.; Fitó, M.; Gutiérrez, V.R.; Ros, E. Mediterranean diet supplemented with nuts reduces waist circumference and shifts lipoprotein subfractions to a less atherogenic pattern in subjects at high cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 2013, 230, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Biofortification of crops with seven mineral elements often lacking in human diets–iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, selenium and iodine. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. World Health Organization. Guideline: Potassium Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka, L.; Allison, S.; Stanga, Z. Basics in clinical nutrition: Water and electrolytes in health and disease. e-SPEN Eur. E-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 6, e259–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesta, M.C.M.; Perles, R.D.; Moreno, D.A.; Muries, B.; López, C.A.; Bastías, E.; Carvajal, M. Minerals in plant food: Effect of agricultural practices and role in human health. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 30, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, J.P.L.; Amaral Souza, F.D.C. Bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba): A new wet tropics nutritional source. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 13, 803–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravia, S.A.M.; Montero, I.F.; Linhares, B.M.; Santos, R.A.; Marcia, J.A.F. Mineralogical Composition and Bioactive Molecules in the Pulp and Seed of Patauá (Oenocarpus bataua Mart.): A Palm from the Amazon. Int. J. Plant Soil Sci. 2020, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, L.O.; Mendes, M.F.; Pereira, C.D.S.S. Avaliação da composição centesimal, mineral e teor de antocianinas da polpa de juçaí (Euterpe edulis Martius). Rev. Eletrônica TECCEN 2011, 4, 05–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, K.O.P.; Oliveira, A.A.; Revorêdo, T.B.; Martins, A.B.N.; Lacerda, E.C.Q.; Freire, A.S.; Monteiro, M.C. Screening of the chemical composition and occurring antioxidants in jabuticaba (Myrciaria jaboticaba) and jussara (Euterpe edulis) fruits and their fractions. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A.; Cruz, A.P.G.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Freitas, S.C.; Taxi, C.M.A.D.; Donangelo, C.M.; Marx, F. Chemical characterization and evaluation of antioxidant properties of Açaí fruits (Euterpe oleraceae Mart.) during ripening. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.A.; Rodrigues, E.; Mercadante, A.Z.; Rosso, V.V. Phenolic Compounds and Carotenoids from Four Fruits Native from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 5072–5084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.S.; Gomes, A.L.; Silva, M.G.; Alves, A.B.; Angol, W.H.D.; Ferrari, R.A.; Pacheco, M.T.B. Antioxidant capacity and chemical characterization of açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) fruit fractions. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 4, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhães, L.R.T.; Sabaa-Srur, A.U.O. Centesimal composition and bioactive compounds in fruits of buriti collected in Pará. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 31, 856–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, T.L.N.; Silva, M.R. Comparison of the physicochemical profiles of buriti from the Brazilian Cerrado and the Amazon region. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 37, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiassi, M.C.E.V.; Souza, V.R.; Lago, A.M.T.; Campos, L.G.; Queiroz, F. Fruits from the Brazilian Cerrado region: Physico-chemical characterization, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activities, and sensory evaluation. Food Chem. 2018, 245, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.P.; Almeida, F.; Silva, L.C.R.D.; Vieira, R.F.; Agostini-Costa, T.D.S. Caracterização da polpa do coquinho-azedo (Butia). Rev. Bras. De Frutic. 2008, 30, 827–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, T.S.; Ferreira, D.F.; Flores, D.W.; Bernardi, G.; Link, D.; Barin, J.S.; Wagner, R. Evaluation of composition and quality parameters of jelly palm (Butia odorata) fruits from different regions of Southern Brazil. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.C.; Boschetti, W.; Rampazzo, R.; Celso, P.G.; Hertz, P.F.; Rios, A.D.O.; Flores, S.H. Mineral characterization of native fruits from the southern region of Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 34, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bergman, C.; Gray-Scott, D.; Chen, J.J.; Meacham, S. What is next for the dietary reference intakes for bone metabolism related nutrients beyond calcium: Phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and fluoride? Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 49, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenkin, A. Basics in clinical nutrition: Physiological function and deficiency states of trace elements. e-SPEN Eur. E J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 6, e255–e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, V.L.; Gropper, S.S. Effect of chromium nicotinic acid supplementation on selected cardiovascular disease risk factors. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1996, 55, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, G.F. Status of selenium in prostate cancer prevention. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montúfar, R.; Laffargue, A.; Pintaud, J.C.; Hamon, S.; Avallone, S.; Dussert, S. Oenocarpus bataua Mart. (Arecaceae): Rediscovering a source of high oleic vegetable oil from Amazonia. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.S.M.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.; Arranz, S.; Alves, R.E.; Brito, E.S.; Oliveira, M.S.; Saura-Calixto, F. Açaí (Euterpe oleraceae) ‘BRS Pará’: A tropical fruit source of antioxidant dietary fiber and high antioxidant capacity oil. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2100–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portinho, J.A.; Zimmermann, L.M.; Bruck, M.R. Efeitos benéficos do açaí. Int. J. Nutrol. 2012, 5, 015–020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rezaire, A.; Robinson, J.C.; Bereau, D.; Verbaere, A.; Sommerer, N.; Khan, M.K.; Fils-Lycaon, B. Amazonian palm Oenocarpus bataua (“patawa”): Chemical and biological antioxidant activity—Phytochemical composition. Food Chem. 2014, 149, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.M.M.; Pereira, F.T.; Pereira, E.C.; Mendonça, C.J.S. Óleo de buriti: Índice de qualidade nutricional e efeito antioxidante e antidiabético. Rev. Virtual De Quím. 2020, 12, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauss, D.J. Oral lipid-based formulations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2007, 59, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, O.M.; Crum, M.F.; McEvoy, C.L.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Williams, H.D.; Pouton, C.W.; Porter, C.J. 50 years of oral lipid-based formulations: Provenance, progress and future perspectives. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 101, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.F.G.; Alves, R.E.; Méndez, M.V.R. Minor components in oils obtained from Amazonian palm fruits. Grasas Y Aceites 2013, 64, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.F.G.; Marmesat, S.; Brito, E.S.; Alves, R.E.; Dobarganes, M.C. Major components in oils obtained from Amazonian palm fruits. Grasas Y Aceites 2013, 64, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, N.P.B.; Fregapane, G.; Moya, M.D.S. Bioactive compounds, volatiles and antioxidant activity of virgin Seje oils (Jessenia bataua) from the Amazonas. J. Food Lipids 2009, 16, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, M.; Akram, S.; Hasany, S.M. Seje (Oenocarpus/Jessenia bataua) Palm Oil. In Fruit Oils: Chemistry and Functionality; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 883–898. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, A.G.; Silva, K.A.; Silva, L.O.; Costa, A.M.; Akil, E.; Coelho, M.A.; Torres, A.G. Jussara berry (Euterpe edulis M.) oil-in-water emulsions are highly stable: The role of natural antioxidants in the fruit oil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, C.E. Factors Influencing the Stability and Marketability of a Novel, Phytochemical-Rich Oil from the Açai Palm Fruit (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). Ph.D. Thesis, Texas University, Texas, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, D.D.S.; Klauck, V.; Campigotto, G.; Alba, D.F.; Reis, J.H.; Gebert, R.R.; Silva, A.S. Benefits of the inclusion of açai oil in the diet of dairy sheep in heat stress on health and milk production and quality. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 84, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.M.; Sampaio, K.A.; Taham, T.; Rocco, S.A.; Ceriani, R.; Meirelles, A.J. Characterization of oil extracted from buriti fruit (Mauritia flexuosa) grown in the Brazilian Amazon region. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.L.; Rodrigues, A.M.C.; Freitas, R.A.; Meirelles, A.J.A.; Darnet, S.H.; Silva, L.H.M. Alternative sources of oils and fats from Amazonian plants: Fatty acids, methyl tocols, total carotenoids and chemical composition. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.B.; Oliveira, W.S.; Araújo, R.L.; França, A.C.H.; Pertuzatti, P.B. Buriti (Mauritia flexuosa L.) pulp oil as an immunomodulator against enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 149, 112330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, J.D.A.; Oliveira, T.T.D.S.; Santos, J.G.D.S.D.; Gaspar, M.R.G.R.D.C.; Vieira, V.D.A.; Rodrigues, E.C.; Faria, R.A.P.G.D. Fatty acid profile and physicochemical characterization of buriti oil during storage. Ciência Rural 2020, 50, e20190997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiglo, A.G.; Sikorska, E.; Khmelinskii, I.; Sikorski, M. Tocopherol content in edible plant oils. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2007, 57, 157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Firestone, D. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Oils, Fats, and Waxes; AOCS Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Azzi, A. Tocopherols, tocotrienols and tocomonoenols: Many similar molecules but only one vitamin E. Redox Biol. 2019, 26, 101259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaedi, E.; Foshati, S.; Ziaei, R.; Beigrezaei, S.; Varkaneh, H.K.; Ghavami, A.; Miraghajani, M. Effects of phytosterols supplementation on blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 39, 2702–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, S.A.; Sichieri, R.; Moreira, A.S.B.; Souza, D.O.; Cabral, C.T.F.; Gianinni, D.T.; Cunha, D.B. Phytosterol-enriched milk lowers LDL-cholesterol levels in Brazilian children and adolescents: Double-blind, cross-over trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 27, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumolt, J.H.; Rideout, T.C. The lipid-lowering effects and associated mechanisms of dietary phytosterol supplementation. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 5077–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.; Shamloo, M.; MacKay, D.S.; Rideout, T.C.; Myrie, S.B.; Plat, J.; Weingärtner, O. Progress and perspectives in plant sterol and plant stanol research. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 725–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.B.; Lu, Q.Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Aqueous enzymatic extraction of oil and protein hydrolysates from roasted peanut seeds. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, U.; Bronte, V. Control of immune response by amino acid metabolism. Immunol. Rev. 2010, 236, 243–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindseth, G.; Helland, B.; Caspers, J. The effects of dietary tryptophan on affective disorders. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 29, 02–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Protein and Amino Acid Requirements in Human Nutrition; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Volume 935. [Google Scholar]

- Balick, M.J.; Gershoff, S.N. Nutritional evaluation of the Jessenia bataua palm: Source of high-quality protein and oil from tropical America. Econ. Bot. 1981, 35, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauss, A.G. Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.): A macro and nutrient rich palm fruit from the Amazon rain forest with demonstrated bioactivities in vitro and in vivo. In Bioactive Foods in Promoting Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCusker, S.; Buff, P.R.; Yu, Z.; Fascetti, A.J. Amino acid content of selected plant, algae and insect species: A search for alternative protein sources for use in pet foods. J. Nutr. Sci. 2014, 3, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, A.V.; Rocha, J.A.; Santos, K.T.; Freitas, J.F.L.; Almeida, C.A.; Ribeiro, B.; Júnior, A.F.M. Comparative Studies Between Mauritia flexuosa and Mauritiella Armata. Pharmacogn. J. 2019, 11, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, G.A.B.; Xavier, A.A.O.; Neves, L.C.; Benassi, M.D.T. Caracterização físico-química de polpas de frutos da Amazônia e sua correlação com a atividade anti-radical livre. Rev. Bras. De Frutic. 2010, 32, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.V.; Fernandes, C.C.; Lopes, L.M.; Sousa, A.H. Use of plant oils from the southwestern Amazon for the control of maize weevil. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2015, 63, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.V.; Silveira, T.F.; Sousa, S.H.B.; Moraes, M.R.; Godoy, H.T. Phenolic composition and antioxidant capacity of bacaba genotypes. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 54, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, S.H.B.; Mattietto, R.A.; Chisté, R.C.; Carvalho, A.V. Phenolic compounds are highly correlated to the antioxidant capacity of genotypes of Oenocarpus bacaba Mart. fruits. Food Res. Int. 2018, 108, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauchen, J.; Bortl, L.; Huml, L.; Miksatkova, P.; Doskocil, I.; Marsik, P.; Kokoska, L. Phenolic composition, antioxidant and anti-proliferative activities of edible and medicinal plants from the Peruvian Amazon. Rev. Bras. De Farmacogn. 2016, 26, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.S.A. Bioactive compounds and health benefits of some palm species traditionally used in Africa and the Americas—A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 224, 202–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rufino, M.S.M.; Alves, R.E.; Brito, E.S.; Jiménez, J.P.; Calixto, F.S.; Filho, J.M. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacities of 18 non-traditional tropical fruits from Brazil. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.G.S.; Machado, M.T.C.; Silva, V.M.; Sartoratto, A.; Rodrigues, R.A.F.; Hubinger, M.D. Physical properties and morphology of spray dried microparticles containing anthocyanins of jussara (Euterpe edulis Martius) extract. Powder Technol. 2016, 294, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, D.V.; Fraga, S.; Antelo, F. Thermal degradation kinetics of anthocyanins extracted from juçara (Euterpe edulis Martius) and “Italia” grapes (Vitis vinifera L.), and the effect of heating on the antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 836–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vieira, G.S.; Marques, A.S.; Machado, M.T.; Silva, V.M.; Hubinger, M.D. Determination of anthocyanins and non-anthocyanin polyphenols by ultra-performance liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (UPLC/ESI–MS) in jussara (Euterpe edulis) extracts. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2135–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, M.; Gonzaga, L.V.; Souza, V.; Farina, M.; Vitali, L.; Micke, G.A.; Fett, R. Neuroprotective effect of juçara (Euterpe edulis Martius) fruits extracts against glutamate-induced oxytosis in HT22 hippocampal cells. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agawa, S.; Sakakibara, H.; Iwata, R.; Shimoi, K.; Hergesheimer, A.; Kumazawa, S. Anthocyanins in mesocarp/epicarp and endocarp of fresh açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) and their antioxidant activities and bioavailability. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2011, 17, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Thakali, K.M.; Xie, C.; Kondo, M.; Tong, Y.; Ou, B.; Wu, X. Bioactivities of açaí (Euterpe precatoria Mart.) fruit pulp, superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties to Euterpe oleracea Mart. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataglion, G.A.; Silva, F.M.; Eberlin, M.N.; Koolen, H.H. Determination of the phenolic composition from Brazilian tropical fruits by UHPLC—MS/MS. Food Chem. 2015, 180, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.T.B.C.; Campos, D.C.D.S.; Mendes, J.K.S.; Urnhani, C.O.; Araújo, K.G. Qualidade de frutos processados artesanalmente de açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) e bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba Mart.). Rev. Bras. De Frutic. 2015, 37, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvalho, A.V.; Silveira, T.F.; Mattietto, R.D.A.; Oliveira, M.D.S.P.; Godoy, H.T. Chemical composition and antioxidant capacity of açaí (Euterpe oleracea) genotypes and commercial pulps. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, G.A.; Cuenca, C.E.N.; Vincken, J.P.; Gruppen, H. Polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) from Colombia. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, M.F.; Romualdo, G.R.; Vanderveer, L.A.; Barraza, J.F.; Cukierman, E.; Clapper, M.L.; Barbisan, L.F. Lyophilized açaí pulp (Euterpe oleracea Mart) attenuates colitis-associated colon carcinogenesis while its main anthocyanin has the potential to affect the motility of colon cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minighin, E.C.; Souza, K.F.; Valenzuela, V.D.C.T.; Silva, N.D.O.C.; Anastácio, L.R.; Labanca, R.A. Effect of in vitro gastrointestinal digestion on the mineral content, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant capacity of commercial pulps of purple and white açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, V.V.; Mercadante, A.Z. Identification and quantification of carotenoids, by HPLC-PDA-MS/MS, from Amazonian fruits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 5062–5072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.A.; Ballus, C.A.; Filho, J.T.; Godoy, H.T. Phytosterols and tocopherols content of pulps and nuts of Brazilian fruits. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1603–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataglion, G.A.; Silva, F.M.; Eberlin, M.N.; Koolen, H.H. Simultaneous quantification of phenolic compounds in buriti fruit (Mauritia flexuosa Lf) by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2014, 66, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, T.L.N.; Silva, M.R.; Agostini-Costa, T.S. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of buriti (Mauritia flexuosa Lf) from the Cerrado and Amazon biomes. Food Chem. 2015, 177, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamacek, F.R.; Lucia, C.M.D.; Silva, B.P.D.; Moreira, A.V.B.; Sant’Ana, H.M.P. Buriti of the cerrado of Minas Gerais, Brazil: Physical and chemical characterization and content of carotenoids and vitamins. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 38, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskow, G.T.; Hoffmann, J.F.; Teixeira, A.M.; Fachinello, J.C.; Chaves, F.C.; Rombaldi, C.V. Bioactive and yield potential of jelly palms (Butia Odorata Barb. Rodr.). Food Chem. 2015, 172, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.F.; Barbieri, R.L.; Rombaldi, C.V.; Chaves, F.C. Butia spp. (Arecaceae): An overview. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 179, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdo, G.R.; Fragoso, M.F.; Borguini, R.G.; Santiago, M.C.P.A.; Fernandes, A.A.H.; Barbisan, L.F. Protective effects of spray-dried açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart) fruit pulp against initiation step of colon carcinogenesis. Food Res. Int. 2015, 77, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Insfran, D.; Brenes, C.H.; Talcott, S.T. Phytochemical composition and pigment stability of Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rejaie, S.S.; Aleisa, A.M.; Sayed-Ahmed, M.M.; Hafez, M.M. Protective effect of rutin on the antioxidant genes expression in hypercholestrolemic male Westar rat. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, C.S.; Canteli, V.C.D.; Hirota, B.C.K.; Campos, R.; Oliveira, V.B.; Kalegari, M.; Miguel, M.D. Potencial antioxidante in vitro das folhas da Bauhinia ungulata L. Rev. De Ciências Farm. Básica E Apl. 2014, 35, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Assessment of the provitamin A contents of foods: The Brazilian experience. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1996, 9, 196–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuong, L.; Franke, A.; Custer, L.; Murphy, S. Momordica cochinchinensis Spreng. (gac) carotenoids de fruits reevaluates. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2006, 19, 664–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.L.D.S.; Lima, K.D.S.C.; Coelho, M.J.; Silva, J.M.; Godoy, R.L.D.O.; Pacheco, S. Avaliação dos efeitos da radiação gama nos teores de carotenoides, ácido ascórbico e açúcares do futo buriti do brejo (Mauritia flexuosa L.). Acta Amaz. 2009, 39, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamano, P.S.; Mercadante, A.Z. Composition of carotenoids from commercial products of caja (Spondias lutea). J. Food Compos. Anal. 2001, 14, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, A.Z.; Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Effects of ripening, cultivar differences, and processing on the carotenoid composition of mango. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1998, 46, 128–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niizu, P.Y.; Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Flowers and leaves of Tropaeolum majus L. as rich sources of lutein. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, S605–S609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caba, Z.T. The concept of superfoods in diet. In Role Altern. Innov. Food Ingred. Prod. Consum. Wellness 2019, 1, 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mditshwa, A.; Magwaza, L.S.; Tesfay, S.Z.; Opara, U.L. Postharvest factors affecting vitamin C content of citrus fruits: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 218, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, M.A.L.; Canniatti-Brazaca, S.G. Quantification of vitamin C and antioxidant capacity of citrus varieties. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 30, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.Y.; Motechin, R.A.; Wiesenfeld, M.Y.; Holz, M.K. The therapeutic potential of resveratrol: A review of clinical trials. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2017, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, A.L.; Pietro, P.F.; Vieira, F.G.K.; Boaventura, B.C.B.; Liz, S.; Borges, G.D.S.C.; Silva, E.L. Acute consumption of juçara juice (Euterpe edulis) and antioxidant activity in healthy individuals. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 17, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeno, A.; Biju, V.; Yoshida, Y. In vivo ROS production and use of oxidative stress-derived biomarkers to detect the onset of diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and diabetes. Free Radic. Res. 2017, 51, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudonne, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutiere, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leba, L.J.; Brunschwig, C.; Saout, M.; Martial, K.; Bereau, D.; Robinson, J.C. Oenocarpus bacaba and Oenocarpus bataua leaflets and roots: A new source of antioxidant compounds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, G.I.; Almajano, M.P. Red fruits: Extraction of antioxidants, phenolic content, and radical scavenging determination: A review. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicácio, A.E.; Rotta, E.M.; Boeing, J.S.; Barizão, É.O.; Kimura, E.; Visentainer, J.V.; Maldaner, L. Antioxidant activity and determination of phenolic compounds from Eugenia involucrata DC. Fruits by UHPLC-MS/MS. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 10, 2718–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, J.A.P.; Oliveira, G.L.D.S.; Lima, L.K.F.; Ramos, C.L.S.; Medeiros, S.R.A.; Lima, A.C.S.D.; Ferreira, P.M.P. In vitro and ex vivo chemopreventive action of Mauritia flexuosa products. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 1, e2051279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, F.D.B.A.; Kloss, L.; Graeve, L. Bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba) phenolic extract induces apoptosis in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line via the mitochondria-dependent pathway. NFS J. 2016, 5, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finco, F.D.A.; Böser, S.; Graeve, L. Antiproliferative activity of Bacaba (Oenocarpus bacaba) and Jenipapo (Genipa americana L.) phenolic extracts: A comparison of assays. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013, 2, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.B.; Novaes, R.D.; Gonçalves, R.V.; Mendonça, B.G.; Santos, E.C.; Ribeiro, A.Q.; Leite, J.P.V. Euterpe edulis extract but not oil enhances antioxidant defenses and protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease induced by a high-fat diet in rats. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 8173876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.P.; Miranda, D.A.; Carnier, M.; Maza, P.K.; Boldarine, V.T.; Rischiteli, A.S.; Oyama, L.M. Low dose of Juçara pulp (Euterpe edulis Mart.) minimizes the colon inflammatory milieu promoted by hypercaloric and hyperlipidic diet in mice. J. Funct. Foods 2021, 77, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udani, J.K.; Singh, B.B.; Singh, V.J.; Barrett, M.L. Effects of Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) berry preparation on metabolic parameters in a healthy overweight population: A pilot study. Nutr. J. 2011, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, H.S.D.; Dias, M.M.S.; Noratto, G.; Talcott, S.; Talcott, S.U.M. Anti-lipidaemic and anti-inflammatory effect of açai (Euterpe oleracea Martius) polyphenols on 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 23, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Kang, J.; Li, Z.; Schauss, A.G.; Badger, T.M.; Nagarajan, S.; Wu, X. The açaí flavonoid velutin is a potent anti-inflammatory agent: Blockade of LPS-mediated TNF-α and IL-6 production through inhibiting NF-κB activation and MAPK pathway. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1184–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobim, M.L.; Barbisan, F.; Fortuna, M.; Teixeira, C.F.; Boligon, A.A.; Ribeiro, E.E.; Cruz, I.B.M. Açai (Euterpe oleracea, Mart.), an Amazonian fruit has antitumor effects on prostate cancer cells. Arch. Biosci. Health 2019, 1, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.V.; Muehlmann, L.A.; Longo, J.P.F.; Silva, J.R.; Fascineli, M.L.; Souza, P.; Azevedo, R.B. Photodynamic therapy mediated by acai oil (Euterpe oleracea Martius) in nanoemulsion: A potential treatment for melanoma. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2017, 166, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinholes, J.; Lemos, G.; Barbieri, R.L.; Franzon, R.C.; Vizzotto, M. In vitro assessment of the antihyperglycemic and antioxidant properties of araçá, butiá and pitanga. Food Biosci. 2017, 19, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubert, L.; Zehetmeyr, M.L.; Pereira, Y.M.N.; Kroning, I.S.; Maia, D.S.V.; Sehn, C.P.; Silva, W.P. Tolerance to benzalkonium chloride and antimicrobial activity of Butia odorata Barb. Rodr. extract in Salmonella spp. isolates from food and food environments. Food Res. Int. 2019, 116, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, D.S.V.; Haubert, L.; Soares, K.S.; Würfel, S.D.F.R.; Silva, W.P. Butia odorata Barb. Rodr. extract inhibiting the growth of Escherichia coli in sliced mozzarella cheese. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 1663–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, D.; Aranha, B.; Chaves, F.; Silva, W. Antibacterial activity of Butiá odorata extracts against pathogenic bacteria. Trends Phytochem. Res. 2017, 1, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros, M.C.; Aquino, J.S.; Soares, J.; Figueiroa, E.B.; Mesquita, H.M.; Pessoa, D.C.; Stamford, T.M. Buriti oil (Mauritia flexuosa L.) negatively impacts somatic growth and reflex maturation and increases retinol deposition in young rats. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2015, 46, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Cai, Y.Z.; Brooks, J.D.; Corke, H. The in vitro antibacterial activity of dietary spice and medicinal herb extracts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 117, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, G.J.; Funke, B.R.; Case, C.L. Microbiologia; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012; Volume 10, pp. 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Polovková, M.; Šimko, P. Determination and occurrence of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde in white and brown sugar by high performance liquid chromatography. Food Control 2017, 78, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leão, K.M.M.; Reis, L.V.C.; Speranza, P.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Ribeiro, A.P.B.; Macedo, J.A.; Macedo, G.A. Physicochemical characterization and antimicrobial activity in novel systems containing buriti oil and structured lipids nanoemulsions. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 24, e00365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.J.; Crespo, J.F.; Cabanillas, B. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids. Food Chem. 2019, 299, 125124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baliga, M.S.; Baliga, B.R.V.; Kandathil, S.M.; Bhat, H.P.; Vayalil, P.K. A review of the chemistry and pharmacology of the date fruits (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1812–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.D.L.; López, N.L.; Grijalva, E.P.G.; Heredia, J.B. Phenolic compounds: Natural alternative in inflammation treatment. A Review. Cogent Food Agric. 2016, 2, 1131412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Virgous, C.; Si, H. Synergistic anti-inflammatory effects and mechanisms of combined phytochemicals. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 69, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Naura, A.S. Potential of phytochemicals as immune-regulatory compounds in atopic diseases: A review. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 173, 113790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon De La Lastra, C.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argentato, P.P.; Morais, C.A.; Santamarina, A.B.; de Cássia César, H.; Estadella, D.; de Rosso, V.V.; Pisani, L.P. Jussara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) supplementation during pregnancy and lactation modulates UCP-1 and inflammation biomarkers induced by trans-fatty acids in the brown adipose tissue of offspring. Clin. Nutr. Exp. 2017, 12, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, A.C.; Oyama, L.M.; Oliveira, J.L.D.; Garcia, M.C.; Rosso, V.V.D.; Amigo, L.S.M.; Pisani, L.P. Jussara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) supplementation during pregnancy and lactation modulates the gene and protein expression of inflammation biomarkers induced by trans-fatty acids in the colon of offspring. Mediat. Inflamm. 2014, 1, 987927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougee, S.; Sanders, A.; Faber, J.; Graus, Y.M.; Van den Berg, W.B.; Garssen, J.; Hoijer, M.A. Decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine production by LPS-stimulated PBMC upon in vitro incubation with the flavonoids apigenin, luteolin or chrysin, due to selective elimination of monocytes/macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 69, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmugam, K.; Holmquist, L.; Steele, M.; Stuchbury, G.; Berbaum, K.; Schulz, O.; Münch, G. Plant-derived polyphenols attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced nitric oxide and tumour necrosis factor production in murine microglia and macrophages. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykouras, L.; Michopoulos, J. Transtornos de ansiedade e obesidade. Psychiatriki 2011, 22, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Pervanidou, P.; Chrousos, G.P. Stress and obesity/metabolic syndrome in childhood and adolescence. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, 21–28. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/17477166.2011.615996 (accessed on 4 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Schrempf, J. A social connection approach to corporate responsibility: The case of the fast-food industry and obesity. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 300–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solinas, G. Molecular pathways linking metabolic inflammation and thermogenesis. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, T.; Sedjo, R.L. Body fatness as a cause of cancer: Epidemiologic clues to biologic mechanisms. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2015, 22, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuutila, A.M.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Aarni, M.; Oksman-Caldentey, K.M. Comparison of antioxidant activities of onion and garlic extracts by inhibition of lipid peroxidation and radical scavenging activity. Food Chem. 2013, 81, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Upadhyay, A.K.; Prasad, K.; Bahadur, A.; Rai, M. Variability of carotenes, vitamin C, E and phenolics in Brassica vegetables. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2007, 20, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Moussa, N.M.; Chen, L.; Mo, H.; Shastri, A.; Su, R.; Shen, C.L. Novel insights of dietary polyphenols and obesity. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyama, L.M.; Silva, F.P.D.; Carnier, J.; Miranda, D.A.; Santamarina, A.B.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Rosso, V.V. Juçara pulp supplementation improves glucose tolerance in mice. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2016, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamarina, A.B.; Jamar, G.; Mennitti, L.V.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Cardoso, C.M.; Rosso, V.V.; Pisani, L.P. Polyphenols-rich fruit (Euterpe edulis Mart.) prevents peripheral inflammatory pathway activation by the short-term high-fat diet. Molecules 2019, 24, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamar, G.; Santamarina, A.B.; Mennitti, L.V.; Cesar, H.C.; Oyama, L.M.; Rosso, V.V.; Pisani, L.P. Bifidobacterium spp. reshaping in the gut microbiota by low dose of juçara supplementation and hypothalamic insulin resistance in Wistar rats. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IARC. All Cancers-International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2020. Available online: https://www.iarc.who.int/faq/latest-global-cancer-data-2020-qa/ (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Marmot, M.; Atinmo, T.; Byers, T.; Chen, J.; Hirohata, T.; Jackson, A.; James, W.; Kolonel, L.; Kumanyika, S.; Leitzmann, C.; et al. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kushi, L.H.; Doyle, C.; McCullough, M.; Rock, C.L.; Wahnefried, W.D.; Bandera, E.V.; American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. American Cancer Society Guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention: Reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 30–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, P.S.; Thompson, R.L.; Wiseman, M.J. Recent evidence for colorectal cancer prevention through healthy food, nutrition, and physical activity: Implications for recommendations. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2012, 1, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.J.A.; Domínguez, F.; Carrancá, A.G. Rutin exerts antitumor effects on nude mice bearing SW480 tumor. Arch. Med. Res. 2013, 4, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.; Silva, L. Health benefits of nongallated and gallated flavan-3-ols: A prospectus. In Recent Advances in Gallate Research; Kinsey, A.L., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1–191. [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The pharmacological potential of rutin. Saudi Pharm. J. 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition (g 100 g−1) (Fresh Weigh) | Bacaba (O. bacaba) | Patawa (O. bataua) | Juçara (E. edulis) | Açaí (E. oleracea) | Buriti (M. flexuosa) | Buritirana (M. armata) | Butiá (B. odorata) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 30.36 | 33.50 | 88.90 | 37.17 | 79.35 | 54.78 | 84.39 |

| Ash | 1.53 | 1.10 | 0.38 | 1.64 | 1.01 | 1.58 | 0.72 |

| Lipids | 21.02 | 14.40 | 4.36 | 8.06 | 7.72 | 21.01 | 2.18 |

| Proteins | 4.61 | 4.90 | 0.90 | 5.30 | 1.43 | 5.96 | 0.60 |

| Total Fiber | - | 29.70 | 27.10 | - | 6.02 | 65.46 | 1.31 |

| * Carbohydrates | 42.48 | 46.10 | 5.46 | 47.83 | 10.49 | 16.67 | 12.11 |

| pH | 5.83 | - | 4.47 | 5.23 | 4.05 | - | 3.17 |

| ** Total Acidity | 0.22 | - | 0.48 | 1.20 | 0.47 | - | 2.17 |

| Soluble Solids (°Brix) | - | - | 3.03 | 6.46 | 4.33 | - | 15.50 |

| Energy Value (kcal 100 g−1) | 377.54 | 333.60 | 64.68 | 285.06 | 117.16 | 368.78 | 70.46 |

| Minerals (mg 100 g−1) | |||||||

| Calcium (Ca) | 3.80 | 2.35 | 76.40 | 462.00 | 80.49 | 65.19 | 16.80 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 7.80 | 41.23 | 47.4 | 317.00 | 40.34 | 49.12 | 12.50 |

| Potassium (K) | 173.35 | 2.17 | 419.10 | 930.00 | 218 | 672.65 | 462.4 |

| Sodium (Na) | 1.90 | 71.21 | 19.30 | 6.80 | 11.25 | - | Trace |

| Phosphorus (P) | Trace | 41.23 | 41.20 | 186.00 | 6.90 | - | Trace |

| Nickel (Ni) | - | n.d. | 1.00 | - | 0.06 | - | Trace |

| Manganese (Mn) | 0.67 | 0.61 | 3.10 | 45.00 | 1.79 | 3.55 | 0.03 |

| Iron (Fe) | 0.28 | 1.84 | 46.60 | 17.80 | 1.77 | 2.88 | 0.01 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 0.35 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 3.70 | 0.60 | 2.15 | 0.03 |

| Cupper (Cu) | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.50 | 2.11 | 0.15 | 0.44 | 0.01 |

| Selenium (Se) | - | Trace | 0.50 | Trace | 0.05 | - | - |

| Chromium (Cr) | - | - | - | - | 0.12 | - | Trace |

| References | [29,81] | [74,82] | [36,83,84] | [6,85,86,87] | [88,89,90] | [61] | [91,92,93] |

| Fatty Acids (%) | Bacaba (O. bacaba) | Patawa (O. bataua) | Juçara (E. edulis) | Açaí (E. oleracea) | Buriti (M. flexuosa) | Butiá (B. odorata) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caproic (C6:0) | - | 0.40 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.01 | 0.16 |

| Caprylic (C8:0) | - | 7.80 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Capric (C10:0) | - | 8.00 | 0.06 | n.d. | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Lauric (C12:0) | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.39 |

| Myristic (C14:0) | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.12 | 1.60 |

| Pentadecanoic (C15:0) | 0.63 | 0.27 | n.d. | 0.07 | 0.07 | n.d. |

| Palmitic (C16:0) | 32.27 | 18.12 | 25.01 | 28.48 | 22.18 | 31.72 |

| Margaric (C17:0) | n.d. | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.38 |

| Stearic (C18:0) | 4.70 | 1.74 | 3.51 | 4.46 | 2.51 | 4.43 |

| Arachidic (C20:0) | 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.79 |

| Behenic (C22:0) | 0.13 | n.d. | 0.08 | - | 0.02 | 1.57 |

| Lignoceric (C24:0) | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 0.09 | 4.37 |

| ∑Saturated | 38.98 | 36.65 | 29.14 | 30.23 | 27.76 | 45.59 |

| Palmitoleic (C16:1 cis 9) | 1.10 | 0.99 | 1.41 | 5.40 | 0.30 | 2.38 |

| Oleic (C18:1 cis 9) | 46.22 | 72.69 | 50.25 | 52.10 | 75.70 | 41.05 |

| Gondoic (C20:1 cis 11) | n.d. | 0.04 | 0.24 | n.d. | 0.58 | 0.46 |

| ∑Monounsaturated | 47.32 | 73.72 | 51.90 | 57.50 | 76.58 | 43.89 |

| Linoleic (C18:2 cis 9,12) | 20.00 | 1.93 | 25.36 | 44.60 | 4,90 | 24.45 |

| Linolenic (C18:3 cis 9,12,15) | 1.93 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 4.39 | 8.20 | 8.35 |

| ∑Polyunsaturated | 21.93 | 2.72 | 26.10 | 48.05 | 13.10 | 32.80 |

| Tocopherols (mg kg−1) | ||||||

| α-Tocopherol | 148.41 | 56.50 | 571.00 | 645.00 | 614.00 | - |

| β-Tocopherol | trace | 7.80 | 472.00 | - | 761.87 | - |

| γ-Tocopherol | trace | trace | 150.00 | - | 56.71 | - |

| δ-Tocopherol | - | 7.70 | trace | - | 136.00 | - |

| α-tocotrienol | - | n.d. | - | - | 90.00 | - |

| γ-tocotrienol | - | 269.00 | - | - | 12.00 | - |

| δ-tocotrienol | - | - | - | - | 18.00 | - |

| ∑Tocopherols | 148.41 | 341.00 | 1193.00 | 645.00 | 1688.58 | - |

| Phytosterols (mg kg−1) | ||||||

| β-Sitosterol + sitostanol | 76.40 | 479.20 | - | - | 76.60 | - |

| Campesterol | 11.00 | 89.10 | - | - | 6.60 | - |

| Campestanol | 6.00 | trace | - | - | - | - |

| Stigmasterol | 12.60 | 166.10 | - | - | 16.80 | - |

| Δ5-Avenasterol + Δ7-stigmasterol | trace | 434.70 | - | - | trace | - |

| Δ7-Avenasterol | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 106.00 | 1169.10 | - | - | 100.00 | - |

| References | [98,105,106] | [98,107,108] | [36,109] | [45,98,99,110,111] | [7,74,105,112,113,114,115] | [92] |

| Essential Amino Acid (mg g−1 Protein) | DRAMA | Patawa (O. bataua) | Açaí (E. oleracea) | Buriti (M. flexuosa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoleucine | 30.00 | 47.00 | 3.96 | 14.20 |

| Leucine | 59.00 | 78.00 | 7.60 | 23.80 |

| Lysine | 45.00 | 53.00 | 6.45 | 19.00 |

| Methionine | 16.00 | 18.00 | 1.23 | n.d. |

| Cystine | 6.00 | 26.00 | 1.88 | n.d. |

| Phenylalanine + Tyrosine | 38 | 105.00 | 7.79 | n.d. |

| Threonine | 23.00 | 69.00 | 4.89 | 85.50 |

| Valine | 39.00 | 68.00 | 5.27 | 19.00 |

| Tryptophan | 6.00 | 9.00 | 1.54 | 23.80 |

| Histidine | 15.00 | 29.00 | 2.06 | 19.00 |

| Total | 277.00 | 502.00 | 42.67 | 204.30 |

| References | [126] | [127] | [128,129] | [88] |

| Composition and Phenolics Profile (μg g−1) | Bacaba (O. bacaba) | Patawa (O. bataua) | Juçara (E. edulis) | Açaí (E. oleracea) | Buriti (M. flexuosa) | Butiá (B. odorata) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * Total phenolics | 1759.27 b | 306.60 c | 5672.00 c | 3437.40 a | 435.08 c | 1250.30 b |

| ** Total anthocyanins | 34.69 c | 68.04 b | 409.85 b | 110.10 c | 3.10 b | 25.13b |

| (+)-Catechin | 20.21–3.85 c | Trace c | 88.79 a | Trace c | 961.21b | 259.18 c |

| (−)-Epicatechin | 15.50–21.20 b | 8.70 c | 305.60 a | Trace c | 1109.93 b | 211.12 c |

| Quercetin | 1.03–17.65 c | 0.68 c | 239.67 a | 135.66 c | 83.27 b | 360.19 b |

| Myricetin | Trace b | 0.47 c | 660.00 a | n.d. | 145.11 b | Trace b |

| Apigenin | n.d. | 0.05 c | 250.00 a | 12.57 c | 102.48 b | 0.09 c |

| Luteolin | n.d. | 0.03 c | 1020.00 a | 21.61 c | 1060.90 b | 0.44 c |

| Kaempferol | n.d. | 0.08 c | 440.00 a | 5.21 c | 41.54 b | 6.14 b |

| p-Coumaric acid | Trace b | 0.50 c | 20.20 a | 3.08 c | 277.74 b | 0.77 c |

| Caffeic acid | Trace b | 0.50 c | 3.80 c | 2.38 c | 895.53 b | 0.84 b |

| Ferulic acid | 4.77–10.80 b | 0.35 c | 46.00 c | 7.60 c | 184.66 b | 0.33 b |

| Protocatechuic acid | n.d. | n.d. | 66.02 a | 7.17 c | 2175.93 b | Trace b |

| Quinic acid | n.d. | Trace c | Trace c | n.d. | 230.74 b | Trace b |

| Chlorogenic acid | 0.71–64.56 c | 2.32 c | 16.50 a | 9.90 c | 1154.15 b | 290.10 b |

| Gallic acid | 40.45–1.26 c | 0.01 c | 7.50 c | 0.20 a | 0.06 c | 2.34 b |

| Salicylic acid | n.d. | 0.03 c | 2.66 a | n.d. | 0.16 c | n.d. |

| Sinapic acid | 2.15–9.72 b | 0.05 c | 29.90 c | 0.82 c | 0.34 c | 1.47 b |

| Syringic acid | 1.94–3.53 b | 0.70 c | 75.50 c | 19.03 c | 0.4 c | Trace b |

| Vanillic acid | Trace b | 0.98 c | 148.04 a | 46.55 c | 0.11 c | 0.07 b |

| Naringenin | Trace b | 0.02 c | 5.49 a | n.d. | Trace c | 0.24 c |

| Isoquercitrin | n.d. | 2.12 c | 24.77 a | 1.66 c | 5.85 c | n.d. |

| Rutin | 15.20–56.80 b | 0.65 c | 317.20 a | 34.07 c | 1460.00 b | 161.20 c |

| Cyn 3-O-rutinoside | 196.51–96.51 c | 470.00 c | 23.07 a | 1329.00 c | n.d. | Trace b |

| Antioxidant capacity | ||||||

| DPPH (μmol TE g−1) | 601 b | 2292.50 c | 724.92 c | 336.72 c | 1302.00 a | 64.70 c |

| FRAP (μmol FeSO4 g−1) | 65.67 b | 1869.90 c | 1745.33 a | 298.00 c | 8890.00 a | - |

| ABTS (μmol TE g−1) | 57.90 b | 2471.50 c | 64.50 b | 1154.43 c | 70.20 c | - |

| ORAC (μmol TE g−1) | 190.00 b | 1626.70 c | 1266.36 c | 1262.58 c | 2470.00 a | 278.15 c |

| Carotenoids (mg kg−1) | ||||||

| Cis lycopene | - | - | - | 18.70 c | n.d. | Trace b |

| Lycopene | - | - | - | 186.50 c | n.d. | 1.00 b |

| Cis α-carotene | - | - | trace b | n.d. | Trace b | Trace b |

| α-carotene | - | - | 0.60 b | n.d. | 2.35 b | Trace b |

| Cis β-carotene | trace a | - | trace b | trace c | Trace b | 10.20 b |

| β-carotene | 6.47 a | - | 86.12 b | 221.50 c | 52.57 b | 21.70 b |

| Lutein | - | - | 2.97 b | 483.00 c | 226.00 c | 4.70 b |

| Cis lutein | - | - | 0.13 b | trace c | Trace b | Trace b |

| Vitamins | ||||||

| Vitamin A (RE 100 g−1) | - | n.d. | 27.80 b | 300.60 a | 7280.00 b | - |

| Vitamin C (mg 100 g−1) | 30.20 b | n.d. | 186.00 b | 84.00 a | 59.93 b | 503.40 b |

| Ascorbic Acid (mg 100 g−1) | 0.90 b | n.d. | n.d. | 68.50 b | 51.85 b | 63.00 b |

| References | [25,131,132,133,134] | [101,135,136] | [36,38,84,86,137,138,139,140,141] | [6,85,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149] | [6,18,135,150,151,152,153,154] | [15,68,71,155,156] |

| Fruit | Source | Model | Health Effects | Sample Form | Effects | Related Compounds | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacaba | Pulp extract | Cancer cells | Antiadipogenic effect | Lyophilized samples. Phenolic compounds were extracted with a mixture of acetone–water (80:20) (v/v). 140 g/600 mL of solvent/2 h of stirring. | ↓ BPE: inhibits differentiation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. ↓ BPE: Downstabilizes protein expression of PPARγ2 and C/EBPα in a dose-dependent manner. ▪ It was checked that BPE attenuates adipogenesis through downregulation of PPARγ2 and C/EBPα during differentiation’s early to middle stages. | Phenolic compounds (gallic acid) | Lauvai et al. [24] |

| Pulp extract | Cancer cells | Antiproliferative action on breast cancer cells | Lyophilized samples. Phenolic compounds were extracted with a mixture of acetone–water (80:20) (v/v). 20 g/400 mL of solvent/2 h of stirring. | ↓ BPE: It acts in inhibiting cell proliferation mainly through the induction of apoptosis. ▪ The bacaba can be considered a fruit with chemopreventive potential. ▪ Regardless of the dose (p < 0.05), caspases -6, -8, and -9 were activated when correlated to untreated control. | Phenolic compounds (gallic acid) and caspase-activated deoxyribonuclease | Finco et al. [178] | |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro in cells | Antiproliferative effect | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with acetone–water (80:20) (v/v) mixture. 20 g/400 mL of solvent/2 h of stirring. | ↑ BPE demonstrated more significant antiproliferative activity than genipap extract, the target fruit of the same study. ↑ Antiproliferative capacity = IC50 of 649.6 ± 90.3 mg/mL in the MTT test and an IC50 of 1080.97 ± 0.7 mg/mL in the MUH. The MTT assay is more reliable when compared to other tests to assess the antiproliferative action. | Phenolic compounds | Finco et al. [179] | |

| Patawa | Pulp oil | Insects | In vitro insecticidal activity | PPLM | Death of insect (Sitophilus zeamais) after 24 h. | Mono-, sesqui-, and diterpenes, limonoids and meliatoxins, including triterpenes, coumarins, and flavonoids | Santos et al. [132] |

| Juçara | Lyophilized pulp (LEE), the defatted lyophilized pulp (LDEE), and oil (EO) | Rats | Hypocholesterolemic effect in rats and antioxidant | Lyophilized samples (LEE). Oil extraction (18 g of LEE extracted with 600 mL of ethyl ether/12 h) (Soxhlet) (EO). The rest of the freeze-dried extract from the fruit was called LDEE. | ↑ LEE is rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids. ↑ Right after degreasing, LEE and LDEE presented higher levels of anthocyanins and antioxidant capacity in vitro. ↓ The intake of LEE and LDEE, but not EO, attenuated diet-induced NAFLD. ↓ Reducing inflammatory infiltrate, steatosis, and lipid peroxidation in liver tissue. ▪ Only LDEE presented sufficient benefits to treat NAFLD in rats due to the high number of phenols and anthocyanins. | Phenols and anthocyanins | Freitas et al. [180] |

| Juçara juice | Human | Control of fatigue, oxidative stress, and antioxidant | Not reported | JJ ↓ OSI immediately after an HIIT session. JJ ↑ GSH 1 h after an HIIT session. JJ ↑ total phenols and uric acid overtime during an HIIT session. JJ ↓ fatigue following an HIIT session. | Phenols, GSH, and uric acid | Copetti et al. [14] | |

| Juçara juice | Human | Antioxidant | PPLM | ↑ JJ Ingestion promoted an increase in serum antioxidant capacity after one hour. ↑ Significant effects on GPx activity and FRAP results were observed. Interaction effect at time/treatment was observed on lipid peroxidation. | Phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, uric acid, and GSH | Cardoso et al. [171] | |

| Pulp | Rats | Antilipidemic and anti-inflammatory effects | Freeze-dried pulp for supplementation. | JS ↓ the proinflammatory cytokines in the colon. JS ↓ TLR-4 protein content in the colon. JS ↓ proinflammatory cytokines in EPI. ↓ TNF-α in EPI is independent of the LPS level. | Not specified | Silva et al. [181] | |

| Pulp | HT22 hippocampal cells | Neuroprotective | Lyophilized samples. The extracts were obtained with the following solvents: 1: hexane; 2: dichloromethane; 3: ethyl acetate; 4: butanol. | Dichloromethane extraction presented the ↑ levels of phenolics. Hexane extraction presented the ↓ levels of phenolics. ▪ Hexane and dichloromethane extracts exert a neuroprotective effect. ▪ HT22 neuronal cells were treated with crude extract and fractions of juçara fruits. | Phenolic compounds | Schulz et al. [141] | |

| Açaí | Pulp | Human | Lipid-lowering effect | Pasteurized raw açaí pulp was safely consumed in this study at a dose of 100 g twice a day for one month. | Reduced fasting glucose, insulin, TC, LDL, and TC/HDL ratio and postprandial increase in plasma glucose. | Anthocyanins | Udani et al. [182] |

| Concentrated and frozen juice | In vivo and in vitro tests in cell | PPLM | The compounds of interest were concentrated under vacuum using acidified (0.1% HCl) methanol and water. The methanol was evaporated in a rotary evaporator at <40 °C and redissolved in 60:40 (v/v) dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and water, and stored at −80 °C. | ↓ Expression of proinflammatory cytokines. ↓ Generation of reactive oxygen species. ↓ Cellular adhesion molecule. ↓ C/ebpα, C/ebpβ, Klf5, and Srebp1c. | Phenolic compounds (gallic acid), cyanidin-3-glucoside, and cyanidin-3-rutinoside | Martino et al. [183] | |

| Concentrate juice | In vivo and in vitro tests in cell | Antilipidemic and anti-inflammatory effects | Not related. | ↓ Intracellular lipids by PPARƴ2. ↓ Adipogenic transcription factors, mRNA, proinflammatory cytokines. ↑ Adiponectin expression. ▪ The present study led to the discovery of a robust anti-inflammatory flavone, velutin. | Flavonoids, flavones, and velutin | Xie et al. [184] | |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro tests in cancer cell | Antitumor in vitro | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with an ethanol–water (70:30) (v/v) mixture. | ↑ Antitumoral effect against PCa DU145 cells involving downregulation of Bcl-2 gene. ▪ The synergism between açai and docetaxel is not so effective. ▪ The results suggest that açaí can be used as a dietary supplement to prevent PCa or disease progression. | Orientin and p-coumaric acid | Jobim et al. [185] | |

| Pulp oil | In vivo and in vitro tests in cancer cell | Anticancer | Data on obtaining açaí oil were not released. For the preparation of the nanoemulsion: 9 g of Tween 80® surfactant; 2 g of açaí oil was mixed under stirring for 5 min at room temperature plus 25 mL of nanopure water, heated to 85 ° C. Then, 15 ml of water at 4 ° C was added. Concentration of 50 mg oil/mL. | ↓ 82% reduction of the tumor when compared to control. ↓ Cell death occurred due to apoptosis/late necrosis. ▪ Important discoveries about the photodynamic properties of açaí oil = new photosensitizer. | Polyphenols (anthocyanin, proanthocyanidin, flavonoids, and lignans) | Fuentes et al. [186] | |

| Butiá | Peel and pulp extract | In vitro tests | Antihyperglycemic and antioxidant | The compounds of interest were extracted with an ethanol–water (98:2) (v/v) mixture. 5 g/20 mL of solvent/5 min of stirring. Posteriorly, evaporated under pressure at 40 °C. Reconstituted with 20 ml of ethanol/water (3:1 (v/v)). | ↓ Butiá extracts were not effective when compared to the control. ↑ Among the fruits used in the study, butiá extract was the most effective in reducing DPPH. ↓ Anthocyanins, phenolic compounds, reducing sugars, and carotenoids were responsible for the α-glucosidase inhibition. | Phenolic compounds (quercetin) and α-glucosidase | Vinholes et al. [187] |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro tests in cancer cell | Antitumor and antioxidant | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with 1 g and 10 ml of solvent in the following proportions: 1: methanol; 2: methanol: water (80:20, v/v); 3: ethyl acetate; 4: acetonitrile; 5: acetonitrile: water (80:20, v/v); 6: ethanol; 7: ethanol: water (80:20, v/v). At 30 ° C for 30 min, in an ultrasonic bath. | ↑ Demonstrated antitumor activity against two cervical cancer cell lines, SiHa and C33a, evaluated by the MTT. ↑ High antioxidant activity. ↑ Positive correlation between the content of phenolic compounds and antitumor activity. | (+)-Catechin, (−)-epicatechin, and rutin | Boeing et al. [15] | |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro Deteriorating and pathogenic microorganisms | Antimicrobial | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with methanol; 30 g/300 mL of solvent/2 h of stirring, then in an ultrasound bath (48 A/15 min). | ↑ Butiá odorata extract showed high antimicrobial activity against the studied Salmonella strains. ↑ The zones of inhibition varied between 8 and 14 mm. | 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furfural and piranone | Haubert et al. [188] | |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro Deteriorating and pathogenic microorganisms | Antimicrobial | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with acetone; 30 g/300 mL of solvent/2 h of stirring (190 rpm). | ↑ The extract of Butiá odorata showed antimicrobial activity against all strains of E. coli; ▪ The phytochemical profile of the extract showed as main compounds Z-10-pentadecenol (80.1%) and palmitic acid (19.4%). ↑ Antimicrobial activity against E. coli both in vitro and in situ. | Z-10-pentadecenol and palmitic acid | Maia et al. [189] | |

| Pulp extract | In vivo and in vitro Deteriorating and pathogenic microorganisms | Antimicrobial | Lyophilized samples. The compounds of interest were extracted with methanol or hexane; 30 g/300 mL of methanol or hexane/2 h of stirring, then in an ultrasound bath (48 A/15 min). BHE: Butiá odorata hexane extract. BME: Butiá odorata methanol extract. | ↑ BHE and BME: antibacterial activity against all tested pathogenic bacteria (S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, B. cereus, S. Typhimurium, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa). ↑ BHE and BME ↓. ↑ BHE: contained γ-sitosterol as a significant component. ▪ Good alternative to synthetic preservatives to increase shelf life and food safety. | γ-sitosterol | Maia et al. [190] | |

| Buriti | Pulp oil | In vitro tests | Antioxidant and antimicrobial | The extracts were obtained from 800 g of fruit pulp during 6 to 8 h of extractions with the following reagents: chloroform (FCB), ethyl acetate (FAB), and ethanol (FEB) (Soxhlet). Antioxidant analysis by the ABTS and FRAP method. | ↑↓ (FCB), (FAB), and (FEB) = moderate antioxidant activity. ↑ Antimicrobial activity, antibiotic-enhancing. ↑ High potential in the development of therapeutic alternatives against resistant bacteria. ↓ Failed to modulate antifungal activity. | Phenolic compounds (catechin, caffeic acid, rutin, orientin, luteolin, and others) and flavones; flavanol; flavanonols; catechins | Nonato et al. [18] |

| Pulp, shell, and endocarp | Rats | In vitro and ex vivo chemopreventive action | Samples lyophilized. The compounds of interest were extracted with methanol (1:10; sample/solvent); 1 g/10 mL of solvent/48 h (stored at 4 °C). | ↑ The antioxidant analysis of the parts of M. flexuosa showed promising chemopreventive potential. ↑ More significant results were found for the bark. ▪ None of the extracts induced lysis of rat erythrocytes, being able to protect blood cells. | Phenol, flavonoid, condensed tannin | Freire et al. [177] | |

| Pulp and bark oil | In vivo and in vitro Deteriorating and pathogenic microorganisms | Antimicrobial | PPLM | ↓ Crude oil has low antimicrobial activity. ↑ Nanoencapsulated oil showed a great increase in antimicrobial activity. ↑ Emulsion technique: increased the antimicrobial activity of buriti oil by 59, 62, and 43% against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia, and Staphylococcus aureus, respectively. ↑ Plant-based products are more efficient for Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative bacteria. | Quercetin, eugenol, vanillin and tannins, ellagic acid, and catechin | Castro et al. [16] | |

| Pulp oil | In vivo and in vitro test in cancer cell | Hydroxypterocarpans with estrogenic activity | Dry pulp. The powdered pulp was defatted three times with n-hexane (2 L) at 40 °C, after which the residue was extracted with ethanol (3 L) for 2 hours at 60 °C. Finally, an ethanol extract (124.8 g) (Soxhlet). | ▪ Lespeflorin G8 was identified as a significant estrogenic compound. ▪ Was found to be a receptor estrogen agonist. ▪ 8-HHP was a partial agonist bound to ER. ▪ First study to have found estrogenic compounds in the buriti oil fraction. | Two hydroxypterocarpans = lespeflorin G8 (LF), 8-hydroxy-homo pterocarpan (8-HHP); and 17β-Estradiol | Shimoda et al. [19] | |

| Crude and refined oil | Rats | Hypocholesterolemic effect in rats | The compounds of interest were extracted with chloroform–methanol (2:1) (v/v); 1 g/20 mL of solvent/3 min. | ↓ Total cholesterol. ↓ LDL. ↓ Triglycerides. ↓ AST. Maternal consumption of buriti oil ↓ weight gain and reflex maturation, but ↑ somatic maturation in newborn rats. ↑ Increases the deposition of serum retinol and liver in the offspring. | Serum retinol and liver retinol | Medeiros et al. [191] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morais, R.A.; Teixeira, G.L.; Ferreira, S.R.S.; Cifuentes, A.; Block, J.M. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Native Brazilian Fruits of the Arecaceae Family and Its Potential Applications for Health Promotion. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194009

Morais RA, Teixeira GL, Ferreira SRS, Cifuentes A, Block JM. Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Native Brazilian Fruits of the Arecaceae Family and Its Potential Applications for Health Promotion. Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194009

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorais, Rômulo Alves, Gerson Lopes Teixeira, Sandra Regina Salvador Ferreira, Alejandro Cifuentes, and Jane Mara Block. 2022. "Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Native Brazilian Fruits of the Arecaceae Family and Its Potential Applications for Health Promotion" Nutrients 14, no. 19: 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194009

APA StyleMorais, R. A., Teixeira, G. L., Ferreira, S. R. S., Cifuentes, A., & Block, J. M. (2022). Nutritional Composition and Bioactive Compounds of Native Brazilian Fruits of the Arecaceae Family and Its Potential Applications for Health Promotion. Nutrients, 14(19), 4009. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14194009