Emerging Role of Nicotinamide Riboside in Health and Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

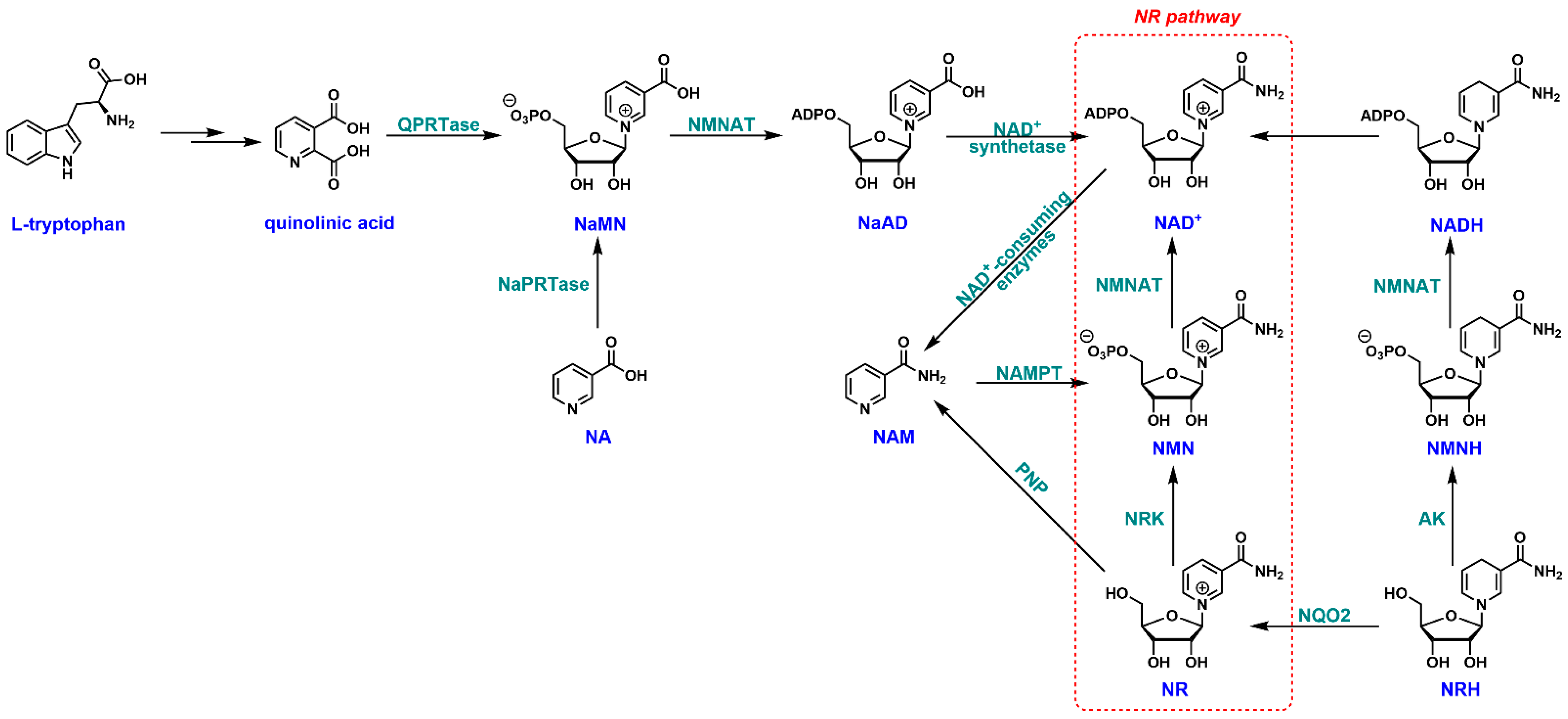

2. NR and NAD+ Biosynthesis

3. Synthesis of NR

3.1. Biosynthesis of NR

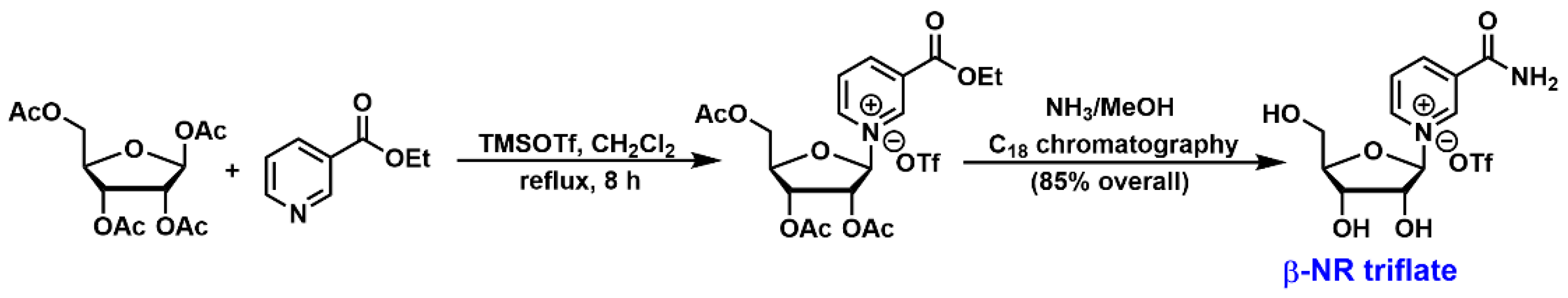

3.2. Chemical Synthesis of NR

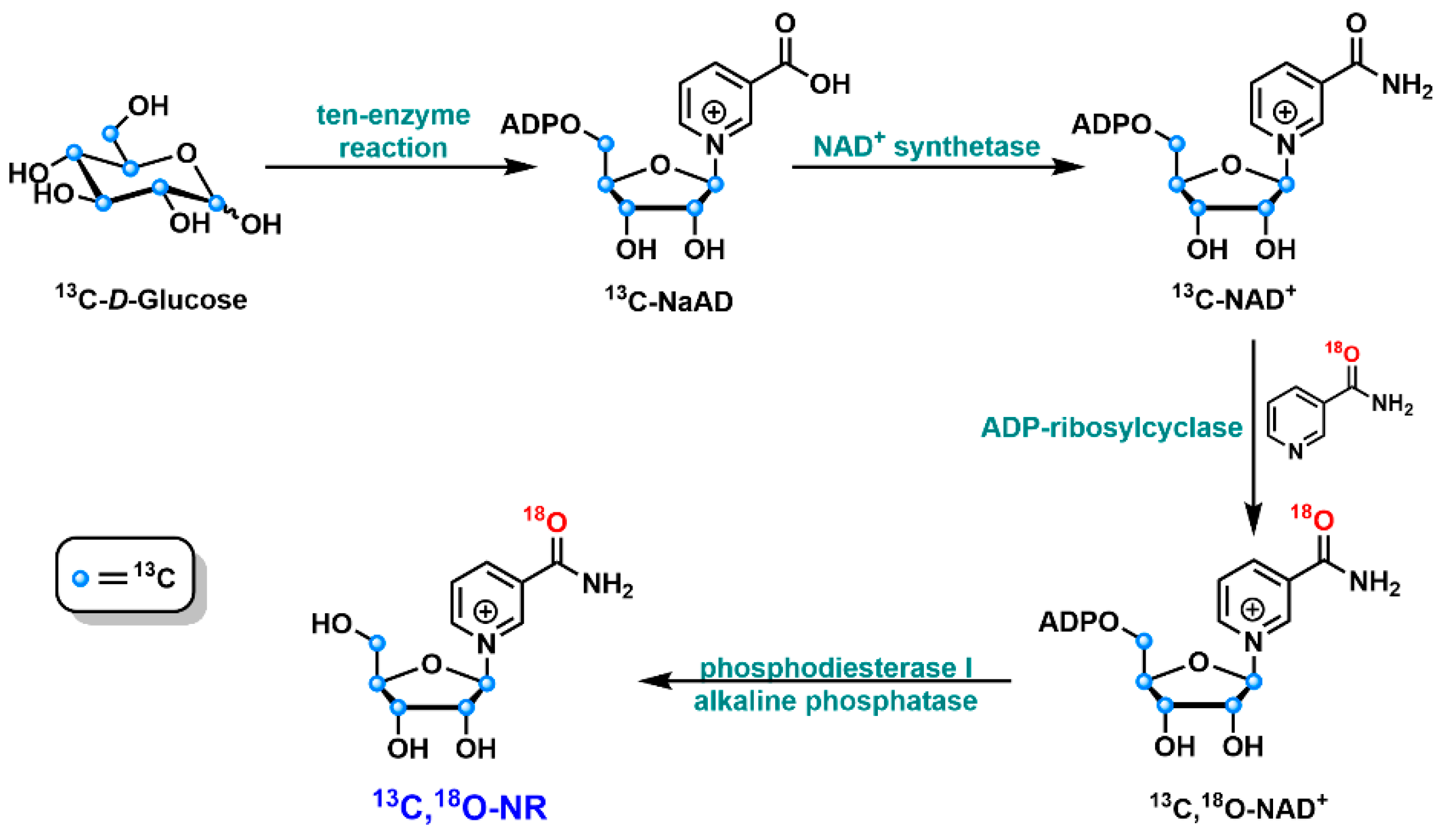

3.3. Chemo-Enzymatic Synthesis of NR

4. NR in Health and Diseases

4.1. Neuroinflammation

4.2. Fibrosis

4.3. Aging

5. NR and COVID-19

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Azzini, E.; Raguzzini, A.; Polito, A. A Brief Review on Vitamin B12 Deficiency Looking at Some Case Study Reports in Adults. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, T.J.; Johnson, C.R.; Koshy, R.; Hess, S.Y.; Qureshi, U.A.; Mynak, M.L.; Fischer, P.R. Thiamine deficiency disorders: A clinical perspective. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1498, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holubiec, P.; Leonczyk, M.; Staszewski, F.; Lazarczyk, A.; Jaworek, A.K.; Rojas-Pelc, A. Pathophysiology and clinical management of pellagra—A review. Folia Med. Cracov. 2021, 61, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Trapani, S.; Rubino, C.; Indolfi, G.; Lionetti, P. A Narrative Review on Pediatric Scurvy: The Last Twenty Years. Nutrients 2022, 14, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewett, D.; Lam-Kamath, K.; Poupault, C.; Khurana, H.; Rister, J. Mechanisms of vitamin A metabolism and deficiency in the mammalian and fly visual system. Dev. Biol. 2021, 476, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenka, P.; Macakova, K.; Kujovska Krcmova, L.; Javorska, L.; Mrstna, K.; Carazo, A.; Protti, M.; Remiao, F.; Novakova, L. OEMONOM Researchers and Collaborators, Vitamin K—Sources, physiological role, kinetics, deficiency, detection, therapeutic use, and toxicity. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souganidis, E. Nobel laureates in the history of the vitamins. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Nicholson, W.K.; Cabana, M.; Chelmow, D.; Coker, T.R.; Davis, E.M.; Donahue, K.E.; Doubeni, C.A.; et al. Vitamin, Mineral, and Multivitamin Supplementation to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2022, 327, 2326–2333. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan, M.; Treiman, K.A.; Kish-Doto, J.; Middleton, J.C.; Coker-Schwimmer, E.J.; Nicholson, W.K. Folic Acid Supplementation for the Prevention of Neural Tube Defects: An Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2017, 317, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annweiler, C.; Dursun, E.; Feron, F.; Gezen-Ak, D.; Kalueff, A.V.; Littlejohns, T.; Llewellyn, D.J.; Millet, P.; Scott, T.; Tucker, K.L.; et al. ‘Vitamin D and cognition in older adults’: Updated international recommendations. J. Intern. Med. 2015, 277, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Carocho, M.; Barros, L.; Zabetakis, I.; Mocan, A.; Tsoupras, A.; Cruz, A.G.; Pimentel, T.C. Implementation of Sustainable Development Goals in the dairy sector: Perspectives on the use of agro-industrial side-streams to design functional foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, R.; Rando, H.M.; Consortium, C.-R.; Greene, C.S. Dietary Supplements and Nutraceuticals under Investigation for COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment. Msystems 2021, 6, e00122-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, R. Dietary supplements and nutraceuticals market growth during the coronavirus pandemic—Implications for consumers and regulatory oversight. PharmaNutrition 2021, 18, 100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belenky, P.; Racette, F.G.; Bogan, K.L.; McClure, J.M.; Smith, J.S.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+. Cell 2007, 129, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogan, K.L.; Brenner, C. Nicotinic acid, nicotinamide, and nicotinamide riboside: A molecular evaluation of NAD+ precursor vitamins in human nutrition. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2008, 28, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trammell, S.A.; Schmidt, M.S.; Weidemann, B.J.; Redpath, P.; Jaksch, F.; Dellinger, R.W.; Li, Z.; Abel, E.D.; Migaud, M.E.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canto, C.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Youn, D.Y.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Cen, Y.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Yamamoto, H.; Andreux, P.A.; Cettour-Rose, P.; et al. The NAD(+) precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaur, P.; Brugg, B.; Mericskay, M.; Li, Z.; Schmidt, M.S.; Vivien, D.; Orset, C.; Jacotot, E.; Brenner, C.; Duplus, E. Nicotinamide riboside, a form of vitamin B3, protects against excitotoxicity-induced axonal degeneration. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 5440–5452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roboon, J.; Hattori, T.; Ishii, H.; Takarada-Iemata, M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Heer, C.D.; O’Meally, D.; Brenner, C.; Yamamoto, Y.; Okamoto, H.; et al. Inhibition of CD38 and supplementation of nicotinamide riboside ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial and astrocytic neuroinflammation by increasing NAD. J. Neurochem. 2021, 158, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trammell, S.A.; Weidemann, B.J.; Chadda, A.; Yorek, M.S.; Holmes, A.; Coppey, L.J.; Obrosov, A.; Kardon, R.H.; Yorek, M.A.; Brenner, C. Nicotinamide Riboside Opposes Type 2 Diabetes and Neuropathy in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollerup, O.L.; Christensen, B.; Svart, M.; Schmidt, M.S.; Sulek, K.; Ringgaard, S.; Stodkilde-Jorgensen, H.; Moller, N.; Brenner, C.; Treebak, J.T.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of nicotinamide riboside in obese men: Safety, insulin-sensitivity, and lipid-mobilizing effects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, D.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Jiang, N.; Altamirano, F.; Szweda, P.A.; Elnwasany, A.; Lee, D.I.; Yoo, H.; Kass, D.A.; Szweda, L.I.; et al. NAD(+) Repletion Reverses Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1629–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heer, C.D.; Sanderson, D.J.; Voth, L.S.; Alhammad, Y.M.O.; Schmidt, M.S.; Trammell, S.A.J.; Perlman, S.; Cohen, M.S.; Fehr, A.R.; Brenner, C. Coronavirus infection and PARP expression dysregulate the NAD metabolome: An actionable component of innate immunity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17986–17996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunewald, M.E.; Chen, Y.; Kuny, C.; Maejima, T.; Lease, R.; Ferraris, D.; Aikawa, M.; Sullivan, C.S.; Perlman, S.; Fehr, A.R. The coronavirus macrodomain is required to prevent PARP-mediated inhibition of virus replication and enhancement of IFN expression. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, S.; Baregzay, B.; Spicer, D.; Singal, P.K.; Khaper, N. Redox-inflammatory synergy in the metabolic syndrome. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, S.; Nisar, S.; Bhat, A.A.; Shah, A.R.; Frenneaux, M.P.; Fakhro, K.; Haris, M.; Reddy, R.; Patay, Z.; Baur, J.; et al. Role of NAD(+) in regulating cellular and metabolic signaling pathways. Mol. Metab. 2021, 49, 101195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtin, N.; Banyai, K.; Thaventhiran, J.; Le Quesne, J.; Helyes, Z.; Bai, P. Repositioning PARP inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 infection(COVID-19); a new multi-pronged therapy for acute respiratory distress syndrome? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 3635–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Schultz, M.B.; Sinclair, D.A. NAD(+) in COVID-19 and viral infections. Trends Immunol. 2022, 43, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, A.; White, D.; Cen, Y. Small Molecule Regulators Targeting NAD(+) Biosynthetic Enzymes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2022, 29, 1718–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, G.; Sauve, A.A. NRH salvage and conversion to NAD(+) requires NRH kinase activity by adenosine kinase. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnasov, O.; Goral, V.; Colabroy, K.; Gerdes, S.; Anantha, S.; Osterman, A.; Begley, T.P. NAD biosynthesis: Identification of the tryptophan to quinolinate pathway in bacteria. Chem. Biol. 2003, 10, 1195–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide: Beyond a redox coenzyme. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2541–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Pereira, J.; Tarrago, M.G.; Chini, C.C.S.; Nin, V.; Escande, C.; Warner, G.M.; Puranik, A.S.; Schoon, R.A.; Reid, J.M.; Galina, A.; et al. CD38 Dictates Age-Related NAD Decline and Mitochondrial Dysfunction through an SIRT3-Dependent Mechanism. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, L.S.; Fuller, L.; Yero, I.L.; Martinez, L. Nicotinamide mononucleotide pyrophosphorylase activity in animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1966, 241, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiss, J.; Handler, P. Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. I. Identification of intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieganowski, P.; Brenner, C. Discoveries of nicotinamide riboside as a nutrient and conserved NRK genes establish a Preiss-Handler independent route to NAD+ in fungi and humans. Cell 2004, 117, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempel, W.; Rabeh, W.M.; Bogan, K.L.; Belenky, P.; Wojcik, M.; Seidle, H.F.; Nedyalkova, L.; Yang, T.; Sauve, A.A.; Park, H.W.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside kinase structures reveal new pathways to NAD+. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.S.; Ratajczak, J.; Doig, C.L.; Oakey, L.A.; Callingham, R.; Da Silva Xavier, G.; Garten, A.; Elhassan, Y.S.; Redpath, P.; Migaud, M.E.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside kinases display redundancy in mediating nicotinamide mononucleotide and nicotinamide riboside metabolism in skeletal muscle cells. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chan, N.Y.; Sauve, A.A. Syntheses of nicotinamide riboside and derivatives: Effective agents for increasing nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide concentrations in mammalian cells. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 6458–6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.; Zhang, H.; Ropelle, E.R.; Sorrentino, V.; Mazala, D.A.; Mouchiroud, L.; Marshall, P.L.; Campbell, M.D.; Ali, A.S.; Knowels, G.M.; et al. NAD+ repletion improves muscle function in muscular dystrophy and counters global PARylation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 361ra139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonkowski, M.S.; Sinclair, D.A. Slowing ageing by design: The rise of NAD(+) and sirtuin-activating compounds. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2016, 17, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.E.; Sinclair, D.A. Restoring stem cells—All you need is NAD(.). Cell Res. 2016, 26, 971–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canto, C.; Auwerx, J. Targeting sirtuin 1 to improve metabolism: All you need is NAD(+)? Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 166–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shats, I.; Williams, J.G.; Liu, J.; Makarov, M.V.; Wu, X.; Lih, F.B.; Deterding, L.J.; Lim, C.; Xu, X.; Randall, T.A.; et al. Bacteria Boost Mammalian Host NAD Metabolism by Engaging the Deamidated Biosynthesis Pathway. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 564–579.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmel, M.; Jovanović, N.; Spitz, U. Nicotinamide Riboside—The Current State of Research and Therapeutic Uses. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud-Gerbetant, J.; Joffraud, M.; Giner, M.P.; Cercillieux, A.; Bartova, S.; Makarov, M.V.; Zapata-Perez, R.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.L.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Migaud, M.E.; et al. A reduced form of nicotinamide riboside defines a new path for NAD(+) biosynthesis and acts as an orally bioavailable NAD(+) precursor. Mol. Metab. 2019, 30, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, D.J., 2nd; Jaiswal, A.K. NRH: Quinone oxidoreductase2 (NQO2). Chem. Biol. Interact. 2000, 129, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.P.; Lin, S.J. Phosphate-responsive signaling pathway is a novel component of NAD+ metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 14271–14281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenky, P.; Stebbins, R.; Bogan, K.L.; Evans, C.R.; Brenner, C. Nrt1 and Tna1-independent export of NAD+ precursor vitamins promotes NAD+ homeostasis and allows engineering of vitamin production. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19710. [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova, V.; Shabalin, K.; Nerinovski, K.; Dolle, C.; Niere, M.; Yakimov, A.; Redpath, P.; Khodorkovskiy, M.; Migaud, M.E.; Ziegler, M.; et al. Generation, Release, and Uptake of the NAD Precursor Nicotinic Acid Riboside by Human Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 27124–27137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, L.J.; Hughes, N.A.; Kenner, G.W.; Todd, A. Codehydrogenases. 2. A Synthesis of Nicotinamide Nucleotide. J. Chem. Soc. 1957, 3727–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeck, R.; Woenckhaus, C. Simple methods for preparing nicotinamide mononucleotide and related analogs. Methods Enzymol. 1980, 66, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tanimori, S.; Ohta, T.; Kirihata, M. An efficient chemical synthesis of nicotinamide riboside (NAR) and analogues. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002, 12, 1135–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchetti, P.; Pasqualini, M.; Petrelli, R.; Ricciutelli, M.; Vita, P.; Cappellacci, L. Stereoselective synthesis of nicotinamide beta-riboside and nucleoside analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004, 14, 4655–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Sauve, A.A. Synthesis of beta-Nicotinamide Riboside Using an Efficient Two-Step Methodology. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2017, 71, 14.14.1–14.14.9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, B.; KOPPETSCH, K.; Perni, R.B. Preparation and Use of Crystalline Beta-d-Nicotinamide Riboside. Google Patents PCT/IB2015/054181, 10 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Makarov, M.V.; Migaud, M.E. Syntheses and chemical properties of beta-nicotinamide riboside and its analogues and derivatives. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 401–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.; Yokose, R.; Cen, Y. Chemo-enzymatic synthesis of isotopically labeled nicotinamide riboside. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 3662–3671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cercillieux, A.; Ciarlo, E.; Canto, C. Balancing NAD(+) deficits with nicotinamide riboside: Therapeutic possibilities and limitations. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiten, O.K.; Wilvang, M.A.; Mitchell, S.J.; Hu, Z.; Fang, E.F. Preclinical and clinical evidence of NAD(+) precursors in health, disease, and ageing. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 199, 111567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ryu, D.; Wu, Y.; Gariani, K.; Wang, X.; Luan, P.; D’Amico, D.; Ropelle, E.R.; Lutolf, M.P.; Aebersold, R.; et al. NAD(+) repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science 2016, 352, 1436–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Pan, Y.; Vempati, P.; Zhao, W.; Knable, L.; Ho, L.; Wang, J.; Sastre, M.; Ono, K.; Sauve, A.A.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside restores cognition through an upregulation of proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1alpha regulated beta-secretase 1 degradation and mitochondrial gene expression in Alzheimer’s mouse models. Neurobiol. Aging 2013, 34, 1581–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Kassahun, H.; Croteau, D.L.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Marosi, K.; Lu, H.; Shamanna, R.A.; Kalyanasundaram, S.; Bollineni, R.C.; Wilson, M.A.; et al. NAD(+) Replenishment Improves Lifespan and Healthspan in Ataxia Telangiectasia Models via Mitophagy and DNA Repair. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E.L.; Newton, R.P.; Axford, A.T. Plasma purine nucleoside phosphorylase in cancer patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 2004, 344, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Wei, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Yang, B.; Wang, Y.; Cordonnier, S.; Mattson, M.P.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. NAD(+) supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and cell senescence in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via cGAS-STING. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2011226118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Lautrup, S.; Cordonnier, S.; Wang, Y.; Croteau, D.L.; Zavala, E.; Zhang, Y.; Moritoh, K.; O’Connell, J.F.; Baptiste, B.A.; et al. NAD(+) supplementation normalizes key Alzheimer’s features and DNA damage responses in a new AD mouse model with introduced DNA repair deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1876–E1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, U.; Evans, J.E.; Pearson, A.; Saltiel, N.; Cseresznye, A.; Darcey, T.; Ojo, J.; Keegan, A.P.; Oberlin, S.; Mouzon, B.; et al. Targeting sirtuin activity with nicotinamide riboside reduces neuroinflammation in a GWI mouse model. Neurotoxicology 2020, 79, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlan, B.A.; Killoy, K.M.; Pehar, M.; Liu, L.; Auwerx, J.; Vargas, M.R. Evaluation of the NAD(+) biosynthetic pathway in ALS patients and effect of modulating NAD(+) levels in hSOD1-linked ALS mouse models. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 327, 113219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obrador, E.; Salvador, R.; Marchio, P.; Lopez-Blanch, R.; Jihad-Jebbar, A.; Rivera, P.; Valles, S.L.; Banacloche, S.; Alcacer, J.; Colomer, N.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside and Pterostilbene Cooperatively Delay Motor Neuron Failure in ALS SOD1(G93A) Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 58, 1345–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Yang, S.J. Supplementation with Nicotinamide Riboside Reduces Brain Inflammation and Improves Cognitive Function in Diabetic Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, J.M.; Stein, D.J.; Medeiros, H.R.; de Oliveira, C.; Torres, I.L.S. Nicotinamide Riboside Neutralizes Hypothalamic Inflammation and Increases Weight Loss without Altering Muscle Mass in Obese Rats under Calorie Restriction: A Preliminary Investigation. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 648893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.C.; Chen, W.X.; Wang, J.; Xia, M.; Jia, Z.C.; Guo, C.; Tang, X.Q.; Li, M.X.; Yin, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside rescues angiotensin II-induced cerebral small vessel disease in mice. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2020, 26, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateuszuk, L.; Campagna, R.; Kutryb-Zajac, B.; Kus, K.; Slominska, E.M.; Smolenski, R.T.; Chlopicki, S. Reversal of endothelial dysfunction by nicotinamide mononucleotide via extracellular conversion to nicotinamide riboside. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 114019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, S.; Pang, N.; Huang, Y.; Ye, M.; Wan, T.; Qiu, Y.; Pei, L.; Jiang, X.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside protects against liver fibrosis induced by CCl4 via regulating the acetylation of Smads signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2019, 225, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Yang, S.J. Nicotinamide riboside regulates inflammation and mitochondrial markers in AML12 hepatocytes. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.X.; Bae, M.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, Y.; Hu, S.; Kang, H.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Nicotinamide riboside, an NAD+ precursor, attenuates the development of liver fibrosis in a diet-induced mouse model of liver fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2451–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Wang, D.D.; Qiu, Y.; Airhart, S.; Liu, Y.; Stempien-Otero, A.; O’Brien, K.D.; Tian, R. Boosting NAD level suppresses inflammatory activation of PBMCs in heart failure. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6054–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Weng, H.; Zheng, J. NAD(+) repletion inhibits the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition induced by TGF-beta in endothelial cells through improving mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2019, 117, 105635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhassan, Y.S.; Kluckova, K.; Fletcher, R.S.; Schmidt, M.S.; Garten, A.; Doig, C.L.; Cartwright, D.M.; Oakey, L.; Burley, C.V.; Jenkinson, N.; et al. Nicotinamide Riboside Augments the Aged Human Skeletal Muscle NAD(+) Metabolome and Induces Transcriptomic and Anti-inflammatory Signatures. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1717–1728.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, M.; Sorrentino, V.; Oh, C.M.; Li, H.; de Lima, T.I.; Zhang, H.; Shong, M.; Auwerx, J. NAD(+) boosting reduces age-associated amyloidosis and restores mitochondrial homeostasis in muscle. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, M.; Miura, M.; Williams, E.; Jaksch, F.; Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T.; Guarente, L. NAD(+) supplementation rejuvenates aged gut adult stem cells. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Dan, X.; Hou, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Wechter, N.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Kimura, R.; Babbar, M.; Demarest, T.; McDevitt, R.; et al. NAD(+) supplementation prevents STING-induced senescence in ataxia telangiectasia by improving mitophagy. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolopikou, C.F.; Kourtzidis, I.A.; Margaritelis, N.V.; Vrabas, I.S.; Koidou, I.; Kyparos, A.; Theodorou, A.A.; Paschalis, V.; Nikolaidis, M.G. Acute nicotinamide riboside supplementation improves redox homeostasis and exercise performance in old individuals: A double-blind cross-over study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Cao, B.; Naval-Sanchez, M.; Pham, T.; Sun, Y.B.Y.; Williams, B.; Heazlewood, S.Y.; Deshpande, N.; Li, J.; Kraus, F.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside attenuates age-associated metabolic and functional changes in hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. Basic mechanisms of neurodegeneration: A critical update. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 457–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.V.; Deng, M.; Ting, J.P. The NLRP3 inflammasome: Molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhao, W. NLRP3 Inflammasome—A Key Player in Antiviral Responses. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.F.; Lautrup, S.; Hou, Y.; Demarest, T.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Mattson, M.P.; Bohr, V.A. NAD(+) in Aging: Molecular Mechanisms and Translational Implications. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 899–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, C.H.; Jung, H.; Kim, E.; Song, H.T.; Lee, J.E. Agmatine ameliorates type 2 diabetes induced-Alzheimer’s disease-like alterations in high-fat diet-fed mice via reactivation of blunted insulin signalling. Neuropharmacology 2017, 113 Pt A, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawson, A.R.; Croft, A.M. Gulf War Illness: Unifying Hypothesis for a Continuing Health Problem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.H.; Al-Chalabi, A. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautrup, S.; Sinclair, D.A.; Mattson, M.P.; Fang, E.F. NAD(+) in Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 630–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Z.; Sun, H.; Xue, T.; Gan, C.; Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ye, T. Liver Fibrosis: Therapeutic Targets and Advances in Drug Therapy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 730176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R.; Flamm, S.L.; Di Bisceglie, A.M.; Bodenheimer, H.C.; Public Policy Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease. Serum activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) as an indicator of health and disease. Hepatology 2008, 47, 1363–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Bao, X.; Lou, Q.; Xie, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, S.; Guo, H.; Jiang, G.; Shi, Q. Nicotinamide riboside exerts protective effect against aging-induced NAFLD-like hepatic dysfunction in mice. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.B.; Pham, T.X.; vanLuling, M.; Kostour, V.; Kang, H.; Corvino, O.; Jang, H.; Odell, W.; Bae, M.; Park, Y.K.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside supplementation exerts an anti-obesity effect and prevents inflammation and fibrosis in white adipose tissue of female diet-induced obesity mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 107, 109058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisberg, E.M.; Tarnavski, O.; Zeisberg, M.; Dorfman, A.L.; McMullen, J.R.; Gustafsson, E.; Chandraker, A.; Yuan, X.; Pu, W.T.; Roberts, A.B.; et al. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 952–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaul, E.; Barron, J. Age-Related Diseases and Clinical and Public Health Implications for the 85 Years Old and over Population. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolchuk, V.I.; Miwa, S.; Carroll, B.; von Zglinicki, T. Mitochondria in Cell Senescence: Is Mitophagy the Weakest Link? EBioMedicine 2017, 21, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.F.; Nghiem, M.; Srinivasan, A. HIV infection decreases intracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NAD]. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 212, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.; Pencina, K.M.; Schultz, M.B.; Li, Z.; Ghattas, C.; Lau, J.; Sinclair, D.A.; Montano, M. Reduced Levels of NAD in Skeletal Muscle and Increased Physiologic Frailty Are Associated with Viral Coinfection in Asymptomatic Middle-Aged Adults. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2022, 89 (Suppl. S1), S15–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, N.; Nie, M.; Pang, H.; Wang, B.; Hu, J.; Meng, X.; Li, K.; Ran, X.; Long, Q.; Deng, H.; et al. Integrated cytokine and metabolite analysis reveals immunometabolic reprogramming in COVID-19 patients with therapeutic implications. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Nilsson-Payant, B.E.; Liu, W.C.; Uhl, S.; Hoagland, D.; Moller, R.; Jordan, T.X.; Oishi, K.; Panis, M.; Sachs, D.; et al. Imbalanced Host Response to SARS-CoV-2 Drives Development of COVID-19. Cell 2020, 181, 1036–1045.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luscher, B.; Verheirstraeten, M.; Krieg, S.; Korn, P. Intracellular mono-ADP-ribosyltransferases at the host-virus interphase. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altay, O.; Arif, M.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; Aydin, M.; Alkurt, G.; Kim, W.; Akyol, D.; Zhang, C.; Dinler-Doganay, G.; et al. Combined Metabolic Activators Accelerates Recovery in Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Kok, K.H.; To, K.K.; Chu, H.; Yang, J.; Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Yip, C.C.; Poon, R.W.; et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020, 395, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yan, L.; Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science 2020, 368, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, H.S.; Kokic, G.; Farnung, L.; Dienemann, C.; Tegunov, D.; Cramer, P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature 2020, 584, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, I.F.; Lung, K.C.; Tso, E.Y.; Liu, R.; Chung, T.W.; Chu, M.Y.; Ng, Y.Y.; Lo, J.; Chan, J.; Tam, A.R.; et al. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir-ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: An open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Parkar, J.; Ansari, A.; Vora, A.; Talwar, D.; Tiwaskar, M.; Patil, S.; Barkate, H. Role of favipiravir in the treatment of COVID-19. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 102, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, U.; Raju, R.; Udwadia, Z.F. Favipiravir: A new and emerging antiviral option in COVID-19. Med. J. Armed. Forces India 2020, 76, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.F.; Stephen, P.; Theriault, J.F.; Wang, R.; Lin, S.X. Novel Coronavirus Polymerase and Nucleotidyl-Transferase Structures: Potential to Target New Outbreaks. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 4430–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esam, Z.; Akhavan, M.; Lotfi, M.; Bekhradnia, A. Molecular docking and dynamics studies of Nicotinamide Riboside as a potential multi-target nutraceutical against SARS-CoV-2 entry, replication, and transcription: A new insight. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1247, 131394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M.K.; Grover, P.; Asdaq, S.M.B.; Mehta, L.; Tomar, R.; Imran, M.; Pathak, A.; Jangra, A.; Sahoo, J.; Alamri, A.S.; et al. Potential role of nicotinamide analogues against SARS-COV-2 target proteins. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 7567–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Route of Administration | Mechanism of Action | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroinflammation | Intracerebro ventricular | suppresses CD38-mediated neuroinflammation by increasing NAD+ levels and suppressing NF-κB in mice | [19] |

| Oral (supplemented with drinking water) (12 mM) for 5 months | reduces NLRP3 inflammasome expression and proinflammatory cytokines in AD mouse model | [66] | |

| Oral (supplemented with drinking water) (12 mM) for 6 months | suppresses neuroinflammation in AD/Polβ mice by reducing the levels of proinflammatory cytokines IL-α, TNFα, MCP-1, IL-1β, MIP-1α and increasing the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 | [67] | |

| Oral (supplemented with diet; 100 µg/kg daily) for 2 months | reduces inflammation in Gulf War Illness mice by increasing the deacetylation of NF-κB p65 subunit and PGC-1α | [68] | |

| Oral (supplemented with diet at 400 mg/kg); Oral (185 mg/kg) | decreases neuroinflammatory markers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) mice models | [69,70] | |

| Oral, via stomach gavage (400 mg/kg) for 6 weeks | reduces the level of amyloid-β precursor protein and inflammatory markers NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 in AD mice models | [71] | |

| Oral (400 mg/kg) for 4 weeks; Oral (supplemented with food 300 mg/kg) for 28 days | reversed the increased levels of TNFα in the hypothalamus of obese rats and cerebral small vessel disease mice | [72,73] | |

| 100 µM for 24 h | suppressed endothelial inflammation by reducing ICAM1 and von Willebrand factor expression in IL-1β and TNFα-stimulated human aortic endothelial cells | [74] | |

| Liver Fibrosis | Oral, via stomach gavage (400 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | reversed the development of CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in C57BL/6 mice by reducing TGF-β and serum ALT levels | [75] |

| 100 µM to 10 mM for 24 h | reduced the levels of proinflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-6, and upregulated the levels of the anti-inflammatory molecule, adiponectin, in AML12 mouse hepatocytes | [76] | |

| Oral (400 mg/kg daily) for 20 weeks | Inhibits activation of HSCs by reducing the levels of fibrotic markers α-smooth muscle actin, collagen 1α1, and collagen 6α1 | [77] | |

| Heart failure and cardiac fibrosis | Oral (2 × 250–1500 mg daily) for 9 days | reduced the expression of proinflammatory IL-6 in PBMCs of individuals with Stage D heart failure | [78] |

| Oral (400 mg/kg) for 6–8 weeks | improves the expression of prohibitin to suppress the progression of TGF-1β-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cardiac fibrosis | [79] | |

| Oral (supplemented with diet at 400 mg/kg) for 4 weeks | improved mitochondrial function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction mice by repleting NAD+ levels | [22] | |

| Aging | Oral (1 g daily) for 21 days | reduces circulatory levels of inflammatory cytokines IL-2, IL-5, IL-6, TNFα and augments skeletal muscle NAD+ without altering its mitochondrial bioenergetics in humans | [80] |

| Oral (400 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | reduces amyloid aggregation, improves mitochondrial membrane potential and function in mammalian cells | [81] | |

| Oral (supplemented with drinking water at 50 mg/kg) for 6 weeks | rejuvenates intestinal stem cells in aged mice by activating SIRT1 and mTORC1 | [82] | |

| Oral (supplemented with drinking water at 12 mM) for 2 months | restores mitochondrial function and homeostasis in ataxia telangiectasia mice models | [83] | |

| Oral (500 mg) | improved physical performance and decreased oxidative stress in old individuals | [84] | |

| Oral (400 mg/kg) for 8 weeks | induces change in hematopoietic stem cells composition of aged mice towards a more youthful state by regulating the levels of mitophagy-promoting genes’ transcription | [85] |

| Treatment Regimen | Description | Type | Status | Clinical Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 g of NR or placebo orally every morning for 14 days | to investigate whether NR supplementation can attenuate the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections in elderly patients | randomized double-blinded case–control trial | Unknown | NCT04407390 |

| 250 mg NR capsules administered twice daily for 10 days | treatment with NR in COVID-19 patients for renal protection | prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical interventional trial | Active, not recruiting | NCT04818216 |

| 2000 mg NR in the form of capsules daily | to examine recovery in people with persistent cognitive and physical symptoms after COVID-19 illness | Double-blinded, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled design | Recruiting | NCT04809974 |

| hydroxychloroquine (standard therapy) + dietary supplement consisting of serine, L-carnitine tartrate, N-acetylcysteine, and NR | metabolic cofactor supplementation and hydroxychloroquine combination in COVID-19 patients | parallel-group, randomized, and open-label study | Recruiting | NCT04573153 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, C.; Donu, D.; Cen, Y. Emerging Role of Nicotinamide Riboside in Health and Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193889

Sharma C, Donu D, Cen Y. Emerging Role of Nicotinamide Riboside in Health and Diseases. Nutrients. 2022; 14(19):3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193889

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Chiranjeev, Dickson Donu, and Yana Cen. 2022. "Emerging Role of Nicotinamide Riboside in Health and Diseases" Nutrients 14, no. 19: 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193889

APA StyleSharma, C., Donu, D., & Cen, Y. (2022). Emerging Role of Nicotinamide Riboside in Health and Diseases. Nutrients, 14(19), 3889. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193889