Free School Meal Improves Educational Health and the Learning Environment in a Small Municipality in Norway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Presence

3.1.1. Attendance

“We have virtually no leave down to the center now, as opposed to what we had before we started with the free school meal.”Informant D.

“We have stopped the traffic to the local store, as that was the lunch place (laughter). Yes, many went there before, now they rarely go.”Informant R.

“I think that presence at school creates a better school environment. Being together when you have a break is important, and this can’t be accomplished if someone leaves.”Informant R.

“They went down to the store at lunchbreak and arrived late for the next lesson, or maybe not coming back at all, this happened particularly at the lower secondary school.”Informant M.

“Some students were absent and there were more factors that influenced them in everyday school life than desired. The fact that they often hung out in the store, and maybe someone could have negative experiences around the police because of…. yes…. shoplifting and so on. If you take this away and the students are present at the school, then at least the opportunity to influence them in a positive direction is considerably greater.”Informant V.

3.1.2. Structure

“The teachers get a different relationship with the students when they sit and eat together. Because then, in a way, you are not the teacher and do not stand and lead the class but sit and eat together and talk about topics from everyday life. So yes, I think it influences the relationship. Positive influence.”Informant W.

“One can make friendships across age groups. I think this is important for the social environment and the feeling of fellowship with others.”Informant B.

3.1.3. Social Relationships

“The fact that they are social during the school meal influences their well-being. It shows that they can talk to whom they want around the table, and you can see that they thrive together. I also believe that the way we organize the school meal helps prevent bullying because all the students are together during the school meal and get to know each other.”Informant P.

3.2. Equality

3.2.1. Shared School Meal

“It is a different calmness, because I think that for this age group it is important to be equal to their peers, and this is what they want to be. When they are offered the same food, they can relax, they do not have to think, oh, what do you bring and what do I bring in the lunch box, and then it is easier to calm down. They can enjoy themselves. They smile and laugh, and they chat with each other, and it seems like they are having a great time around the tables.”Informant L.

3.2.2. Social Equalization

“The school meal with packed lunch is partly exclusionary. When it is a quarter to eleven, and the teacher asks everyone to bring out the packed lunch, and then you realize that you do not have a packed lunch! With the free school meal, this is equalized. Then you have the social factor of eating in groups, which is organized differently than before. In the past, the students sat in the classroom with only the classmates and ate, while now they like to mix classes.”Informant M.

“The biggest difference is the social equalization you get with everyone getting the same food. That’s number one. Number two is the learning effect of sitting around a table and having a conversation with a classmate, or a friend.”Informant V.

“It’s a value they will carry on for the rest of their lives, eating healthy, nutritious food together with others. I think it has even more significance in the future than just for the time being.”Informant W.

“The money the municipality spends on the school meal is money they might save in the long run, because in the future these students, as adults, can function better, be healthier, work more. We will not know the total effect of the free school meal until some years have passed.”Informant I.

“I think it’s good for physical health too because we have healthy and predictable meals. They get food, it’s healthy, and I think that’s good for them. Also, in the future, of course, they get healthy eating habits, they can concentrate on schoolwork, and learn more. In a way, they lay the foundation for a good life.”Informant I.

“You get social equalization that is unique considering backgrounds. You have those who come from low social status together with those from high social status around the same table and have the same opportunities for eating food and having a good time together. We see that this has an effect also with companionship, school well-being, and in relation to the learning environment.”Informant V.

3.3. Peacefulness

3.3.1. Peaceful Lunchtime

“When you enter the canteen, it is a peacefulness, it is such a pleasant atmosphere.”Informant V.

“And then students sit very calmly and quietly and talk together around a table and eat their food in a very nice way.”Informant V.

3.3.2. Peacefulness for Learning

“It is more peaceful in the classroom. It is hard to describe it, because it is like a…, yes there is a completely different calmness around the lessons than it was previously. Completely different calmness.”Informant E.

“The free school meal is very important for the learning environment because it evens out these differences we have had here before. It creates peace for all the students, and those who were perhaps a little restless and who used to go outside the school area in the lunch break, they’ve been in school in recess and enter the classroom together with the others, so it creates a different calmness also when we start the lesson.”Informant E.

4. Discussion

4.1. Presence

4.2. Social Equalization

4.3. Peacefulness

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

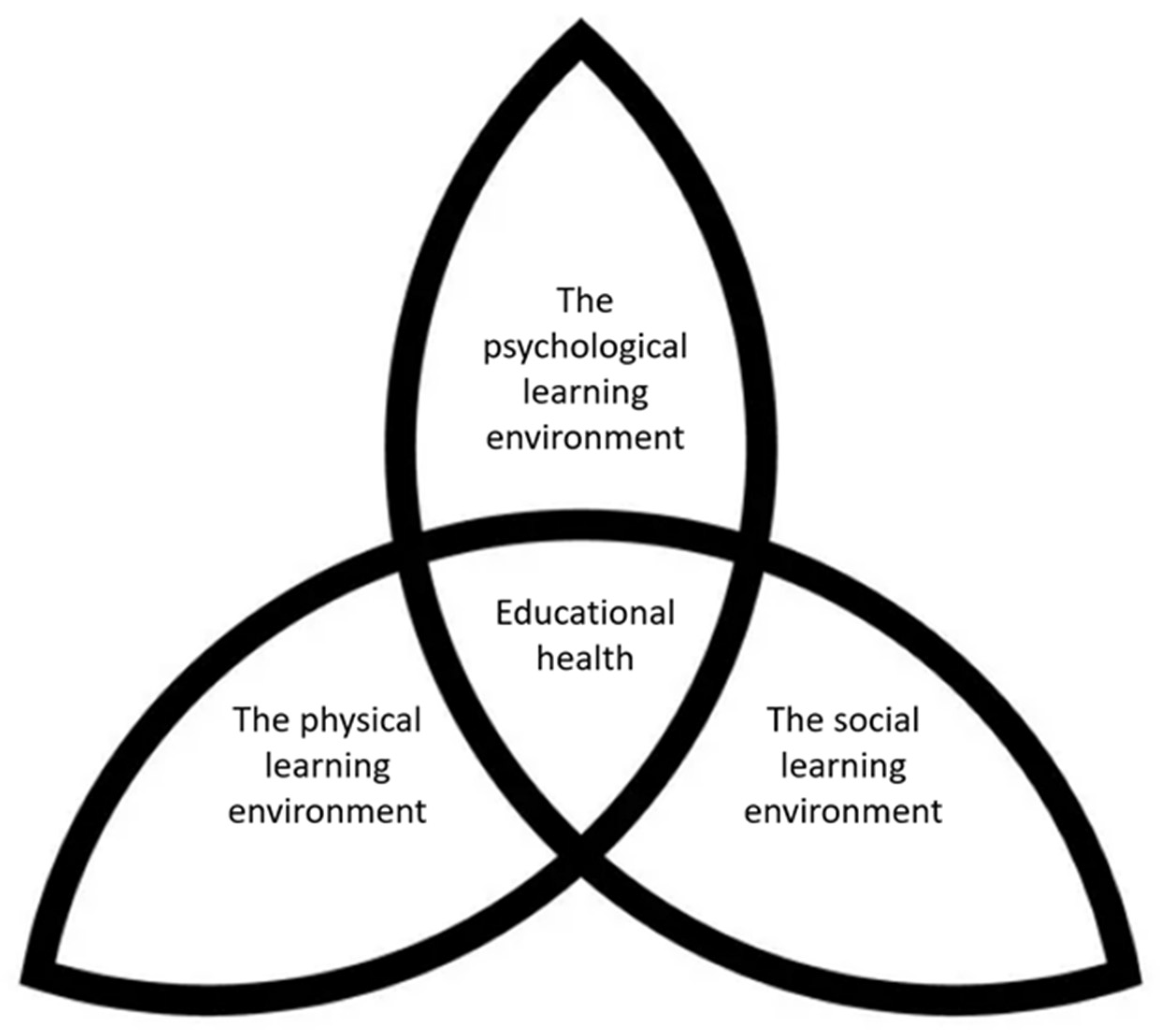

4.5. Educational Health

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Item | Guide Questions/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Research team and reflexivity | ||

| Personal Characteristics | ||

| 1. | Interviewer/facilitator: Greta Heim and Ruth Olaug Thuestad conducted the interviews. | Which author/s conducted the interview or focus group? |

| 2. | Credentials: Both were Master students in Public Health Nutrition at OsloMet University. | What were the researcher’s credentials? e.g., PhD, MD |

| 3. | Occupation: Teacher (G.H.) and inspector for the Norwegian Food Safety Authority (R.O.T.) | What was their occupation at the time of the study? |

| 4. | Gender: Both researchers were female. | Was the researcher male or female? |

| 5. | Experience and training: Both were Master students in Public Health Nutrition at OsloMet University. | What experience or training did the researcher have? |

| Relationship with participants | ||

| 6. | Relationship established: The relationship was established when they began the Master study in Public Health Nutrition, 1-year prior to the study commencement. | Was a relationship established prior to study commencement? |

| 7. | Participant knowledge of the interviewer: The participants knew that the researchers were Master students in Public Health Nutrition. | What did the participants know about the researcher? e.g., personal goals, reasons for doing the research |

| 8. | Interviewer characteristics: The interviewers wanted to examine the school meals’ influence on the learning environment. | What characteristics were reported about the interviewer/facilitator? e.g., bias, assumptions, reasons, and interests in the research topic |

| Domain 2: study design | ||

| Theoretical framework | ||

| 9. | Methodological orientation and Theory: An inductive method with individual semi-structured in-depth interviews was used. | What methodological orientation was stated to underpin the study? e.g., grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, phenomenology, content analysis |

| Participant selection | ||

| 10. | Sampling: A strategic selection of the participants was conducted, as the criteria was that they had experience from working in the school system both before and after the introduction of the free school meal. | How were participants selected? e.g., purposive, convenience, consecutive, snowball |

| 11. | Method of approach: In-depth interviews face-to-face. | How were participants approached? e.g., face-to-face, telephone, mail, email |

| 12. | Sample size: 17 participants. | How many participants were in the study? |

| 13. | Non-participation: One participant could not meet for the interview because of a funeral, but we were able to recruit a substitute in short notice, and we got the number of interviews as planned. | How many people refused to participate or dropped out? Reasons? |

| Setting | ||

| 14. | Setting of data collection: All interviews were collected at the participants workplace. | Where was the data collected? e.g., home, clinic, workplace |

| 15. | Presence of non-participants: Only participant and researcher were present at the interviews. | Was anyone else present besides the participants and researchers? |

| 16. | Description of sample: The participants were teachers, school administrators and school owners. | What are the important characteristics of the sample? e.g., demographic data, date |

| Data collection | ||

| 17. | Interview guide: The interview guide was developed by the authors and tasted at a different school. | Were questions, prompts, guides provided by the authors? Was it pilot tested? |

| 18. | Repeat interviews: Repeat interviews were not carried out. | Were repeat interviews carried out? If yes, how many? |

| 19. | Audio/visual recording: Audio recording was used to collect the data. | Did the research use audio or visual recording to collect the data? |

| 20. | Field notes: Field notes were made after each interview. | Were field notes made during and/or after the interview or focus group? |

| 21. | Duration: The duration of the interviews was 25 min in average. | What was the duration of the interviews or focus group? |

| 22. | Data saturation: Data saturation was not discussed. | Was data saturation discussed? |

| 23. | Transcripts returned: Transcripts were not returned to participants for comments or corrections. | Were transcripts returned to participants for comment and/or correction? |

| Domain 3: analysis and findings: | ||

| Data analysis | ||

| 24. | Number of data coders: The two interviewers coded the data. | How many data coders coded the data? |

| 25. | Description of the coding tree: The authors did provide a description of the coding tree. | Did authors provide a description of the coding tree? |

| 26. | Derivation of themes: Themes were derived from the data. | Were themes identified in advance or derived from the data? |

| 27. | Software: NVivo was used to manage the data. | What software, if applicable, was used to manage the data? |

| 28. | Participant checking: The participants did not provide feedback on the findings. | Did participants provide feedback on the findings? |

| Reporting | ||

| 29. | Quotations presented: Participant quotations were presented to illustrate the findings and each quotation was identified with random letters representing each participant. | Were participant quotations presented to illustrate the themes/findings? Was each quotation identified? e.g., participant number |

| 30. | Data and findings consistent: There was consistency between the data presented and the findings. | Was there consistency between the data presented and the findings? |

| 31. | Clarity of major themes: The major themes were clearly presented in the findings. | Were major themes clearly presented in the findings? |

| 32. | Clarity of minor themes: There is a description of diverse cases as well as a discussion of minor themes. | Is there a description of diverse cases or discussion of minor themes? |

References

- WHO. Food and Nutrition Policy for Schools: A Tool for the Development of School Nutrition Programmes in the European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020. 2013. Available online: https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/ (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Helsedirektoratet. Nasjonal Faglig Retningslinje for Mat og Måltider i Skolen. 2015. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/mat-og-maltider-i-skolen/dokumenter-mat-og-maltider-i-skolen/mat-og-maltider-barneskole-og-SFO-nfr-bokmal.pdf/_/attachment/inline/fdf3025d-2bd6-4b59-8019-e2c0173e1c56:d0563784793afdfd2982cc4811b49a1bb16dcfc7/mat-og-maltider-barneskole-og-SFO-nfr-bokmal.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Dahl, T.; Jensberg, H. Kost i Skole og Barnehage og Betydningen for Helse og Læring: En Kunnskapsoversikt; Nordisk Ministerråd: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Utdanningsdirektoratet. Hva er et Godt Læringsmiljø? Paragraph 1. 2016. Available online: https://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/skolemiljo/psykososialt-miljo/hva-er-et-godt-laringsmiljo/ (accessed on 28 September 2019).

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. Motivasjon–Mestring–Muligheter (Meld. St. 22 (2010–2011)). 2010. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/0b74cdf7fb4243a39e249bce0742cb95/no/pdfs/stm201020110022000dddpdfs.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Engeset, D.; Torheim, L.E.; Øverby, N.C. Samfunnsernæring; Universitetsforl: Oslo, Norway, 2019; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Dalen, M. Intervju Som Forskningsmetode, 2nd ed.; Universitetsforl: Oslo, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. Customer Hub. 2020. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/support-services/customer-hub (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Malterud, K. Kvalitative Metoder i Medisinsk Forskning: En Innføring, 4th ed.; Universitetsforl: Oslo, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. Skolemåltidet i Grunnskolen: Kunnskapsgrunnlag, Nytt- og Kostnadsvirkninger og Vurderinger av Ulike Skolemåltidsmodeller; Kunnskapsdepartementet: Oslo, Norway, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Høiland, R. Påvirker et Felles Skolemåltid Skolemiljøet? Skolematprosjektet i Aust-Agder. Master’s Thesis, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cueto, S. Breakfast and performance. Public Health Nutr. 2001, 4, 1429–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.F.W.; Hecht, A.A.; McLoughlin, G.M.; Turner, L.; Schwartz, M.B. Universal School Meals and Associations with Student Participation, Attendance, Academic Performance, Diet Quality, Food Security, and Body Mass Index: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OsloMet—Storbyuniversitetet. 2018. Ungdata. Available online: http://www.ungdata.no/ (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- OsloMet—Storbyuniversitet. 2013. Ungdata. Available online: http://www.ungdata.no/ (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Opplæringsloven. Lov om Grunnskolen og den Vidaregåande Opplæringa (LOV-1998-07-17-61). 1998. Available online: https://lovdata.no/lov/1998-07-17-61 (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Helsedirektoratet. Mat og Måltider I Skolen. 2015. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/mat-og-maltider-i-skolen (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Haugset, A.S.; Nossum, G. Prosjekt Skolemåltid i Nord-Trøndelag; Trøndelag Forskning og Utvikling: Steinkjer, Norway, 2013; Volume 13, p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Pellikka, K.; Manninen, M.; Taivalmaa, S. School Meals for All. Finnish National Agency for Education. 2019. Available online: https://www.oph.fi/en/statistics-and-publications/publications/school-meals-all (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Grantham-McGregor, S. Can the provision of breakfast benefit school performance? Food Nutr. Bull. 2005, 26, S144–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordahl, T.; Gjerustad, C. Heldagsskolen, Kunnskapsstatus og Forslag til Videre Forskning, NOVA. 2005. Available online: https://docplayer.me/9381541-Heldagsskolen-kunnskapsstatus-og-forslag-til-videre-forskning.html (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Vik, F.N.; Van Lippevelde, W.; Overby, N.C. Free school meals as an approach to reduce health inequalities among 10–12-year-old Norwegian children. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samdal, O.; Bye, H.H.; Torsheim, T.; Birkeland, M.S.; Diseth, Å.R.; Fismen, A.; Haug, E.; Leversen, I.; Wold, B. Sosial Ulikhet i Helse og Læring Blant Barn og Unge. In Resultater fra den Landsrepresentative Spørreskjemaundersøkelsen “Helsevaner Blant Skoleelever; En WHO-Undersøkelse i Flere Land”; HEMIL-Senteret, Universitetet i Bergen: Bergen, Norway, 2012; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1956/6809 (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Mauer, S.; Torheim, L.E.; Terragni, L. Children’s Participation in Free School Meals: A Qualitative Study among Pupils, Parents, and Teachers. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolve, C.S.; Helleve, A.; Bere, E. Gratis Skolemat i Ungdomsskolen—Nasjonal Kartlegging av Skolematordninger og Utprøving av Enkel Modell med et Varmt Måltid; Folkehelseinstituttet, Område for Psykisk og Fysisk Helse Avdeling for Helse Og Ulikhet, Senter for Evaluering av Folkehelsetiltak: Oslo, Norway, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, S.M.; Cinelli, B. Coordinated school health program and dietetics professionals: Partners in promoting healthful eating. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florence, M.D.; Asbridge, M.; Veugelers, P.J. Diet quality and academic performance. J. Sch. Health 2008, 78, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helse-og Omsorgsdepartementet. Folkehelsemeldinga—Gode liv i eit Trygt Samfunn (Meld. St. 19 (2018–2019)). 2019. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/meld.-st.-19-20182019/id2639770/ (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- Lundborg, P.; Rooth, D.-O.; Alex-Petersen, J. Long-Term Effects of Childhood Nutrition: Evidence from a School Lunch Reform. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2021, 89, 876–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øia, T. Ungdomsskoleelever Motivasjon, Mestring og Resultater; Norsk Institutt for Forskning om Oppvekst, Velferd og Aldring: Oslo, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, A. Prestasjonsforskjeller i Kunnskapsløftets Første år: Kjønn, Minoritetsstatus og Foreldres Utdanning (bd. 9/2010); Norsk Institutt for Forskning om Oppvekst, Velferd og Aldring: Oslo, Norway, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Golley, R.; Baines, E.; Bassett, P.; Wood, L.; Pearce, J.; Nelson, M. School lunch and learning behavior in primary schools: An intervention study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storey, H.; Pearce, J.; Ashfield-Watt, P.; Wood, L.; Baines, E.; Nelson, M. A randomized controlled trial of the effect of school food and dining room modifications on classroom behaviour in secondary school children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bellisle, F. Effects of diet on behaviour and cognition in children. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 92 (Suppl. S2), S227–S232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvale, S.; Brinkmann, S. Det Kvalitative Forskningsintervju, 3rd ed.; Gyldendal Akademisk: Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, J.; Carlsson, M.; Nordin, L.L.; Mortensen, L.H. Giver Skolemad Næring for Læring? Læringsmiljø, Trivsel og Kompetence. Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitetsskole, Aarhus Universitet. 2010. Available online: https://pure.au.dk/ws/files/32896790/skolemad_naering_laering.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2020).

- WHO. (u.å.). Constitution. Available online: https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution (accessed on 9 March 2020).

| Informant | Code |

|---|---|

| Teachers | B, D, E, I, O, P, Q, R, Y |

| Administrators | F, G, H, L, M, U, V, W |

| Main Themes | Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| Presence |

|

| Equality |

|

| Peacefulness |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heim, G.; Thuestad, R.O.; Molin, M.; Brevik, A. Free School Meal Improves Educational Health and the Learning Environment in a Small Municipality in Norway. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142989

Heim G, Thuestad RO, Molin M, Brevik A. Free School Meal Improves Educational Health and the Learning Environment in a Small Municipality in Norway. Nutrients. 2022; 14(14):2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142989

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeim, Greta, Ruth Olaug Thuestad, Marianne Molin, and Asgeir Brevik. 2022. "Free School Meal Improves Educational Health and the Learning Environment in a Small Municipality in Norway" Nutrients 14, no. 14: 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142989

APA StyleHeim, G., Thuestad, R. O., Molin, M., & Brevik, A. (2022). Free School Meal Improves Educational Health and the Learning Environment in a Small Municipality in Norway. Nutrients, 14(14), 2989. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142989