The Relationships between Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- (1)

- Study design was cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional study.

- (2)

- Studies that examined the relationships between caregivers’ concern about child weight and their non-responsive feeding practices.

- (3)

- The exposure was caregivers’ concern about child weight, including underweight and overweight.

- (4)

- The outcomes were caregivers’ non-responsive feeding practices.

- (5)

- Included caregivers (e.g., parents and grandparents) who were responsible for the food environment and their children’s eating.

- (6)

- (1)

- Were reviews, editorials, commentaries, letters, or methodological papers.

- (2)

- Were non-English papers.

- (3)

- Did not report the statistics for the relationships between caregivers’ concern about their children’s weight and their non-responsive feeding practices.

- (4)

- Focused on children with diseases that might influence their eating.

2.3. Study Screening and Data Extraction

2.4. Outcomes

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

2.5. Study Quality Assessment

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

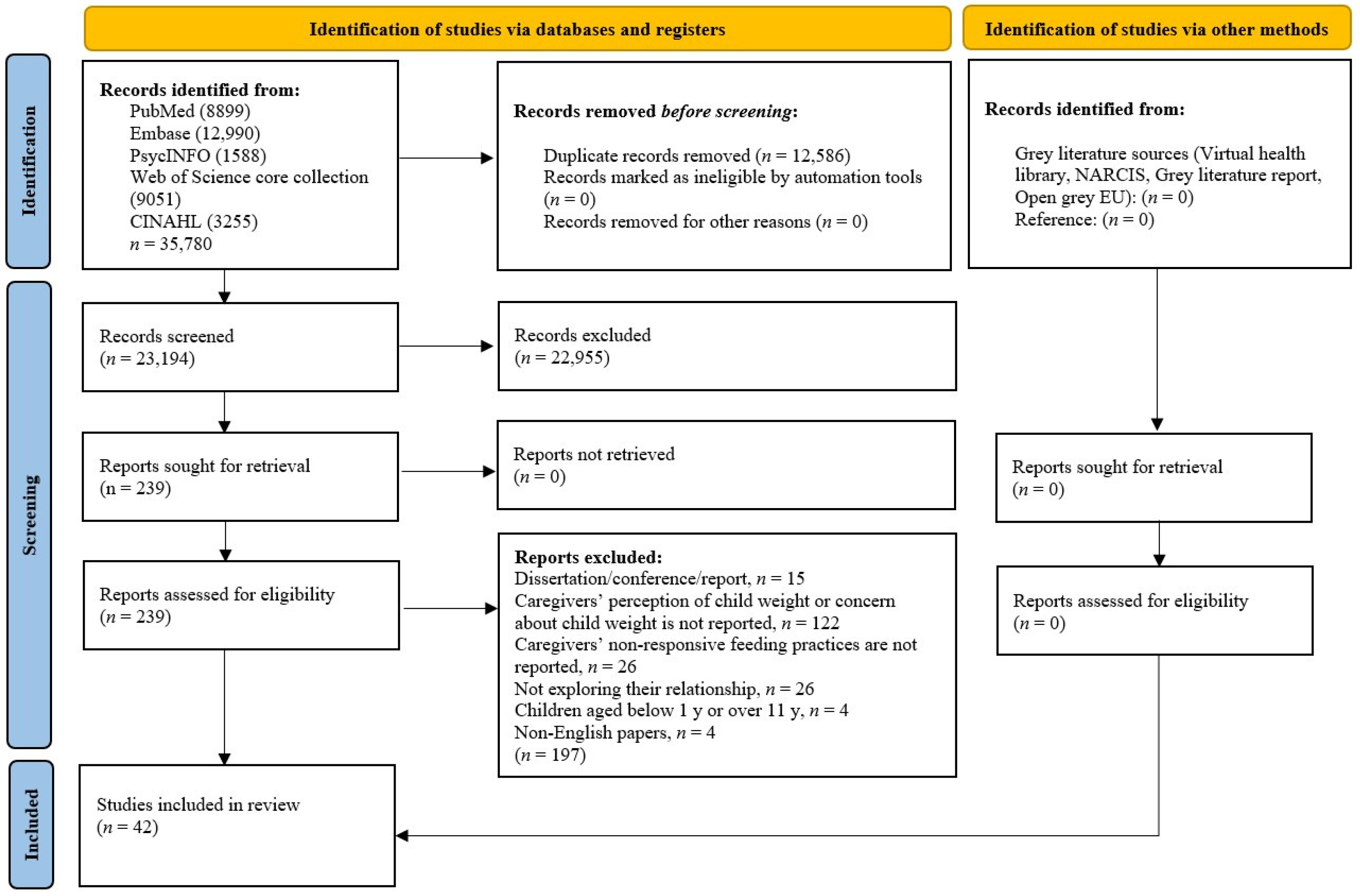

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Characteristics of the Studies

3.3. Measurements for Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices

3.4. Semi-Quantitative Results

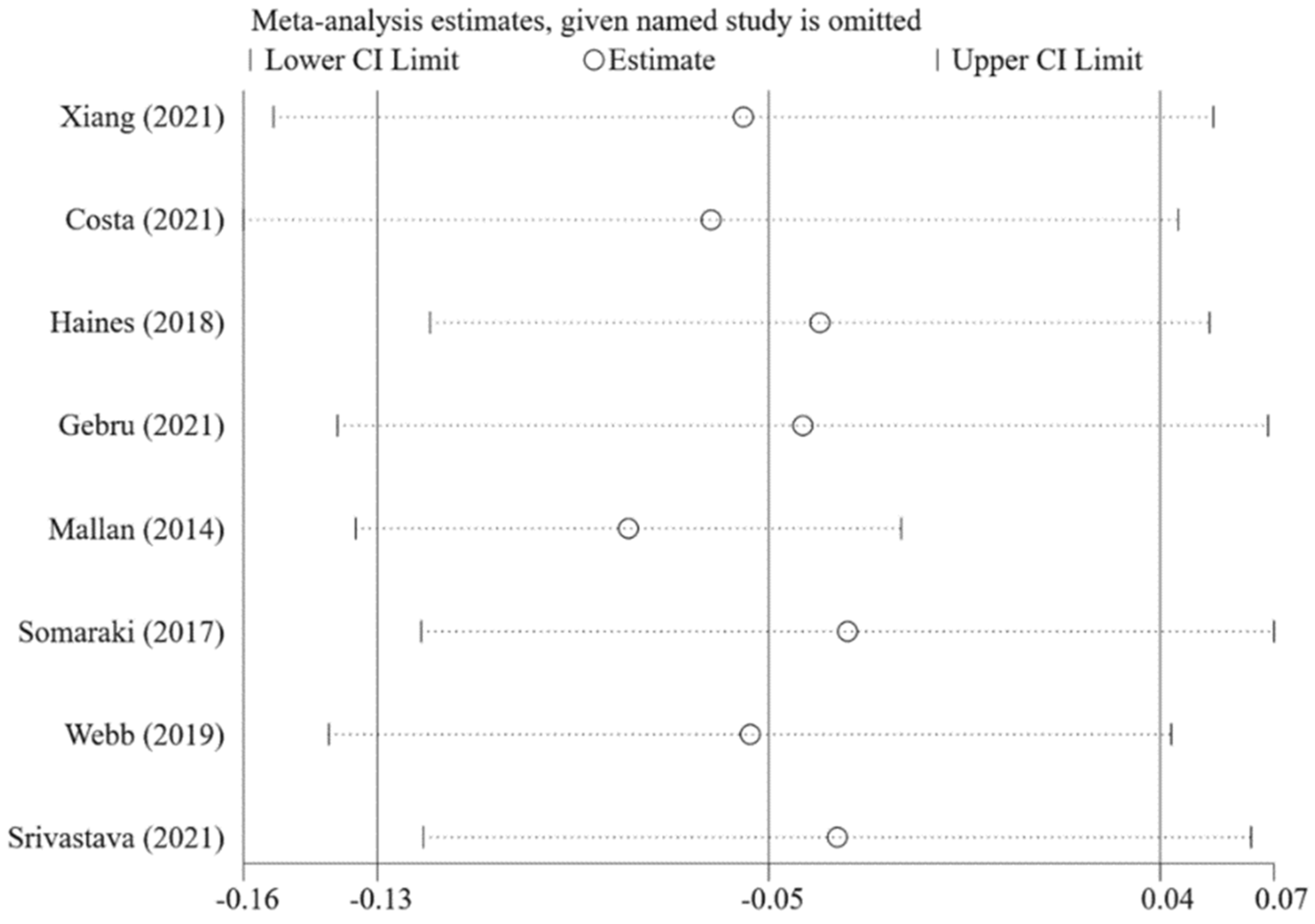

3.5. Results of Meta-Analysis

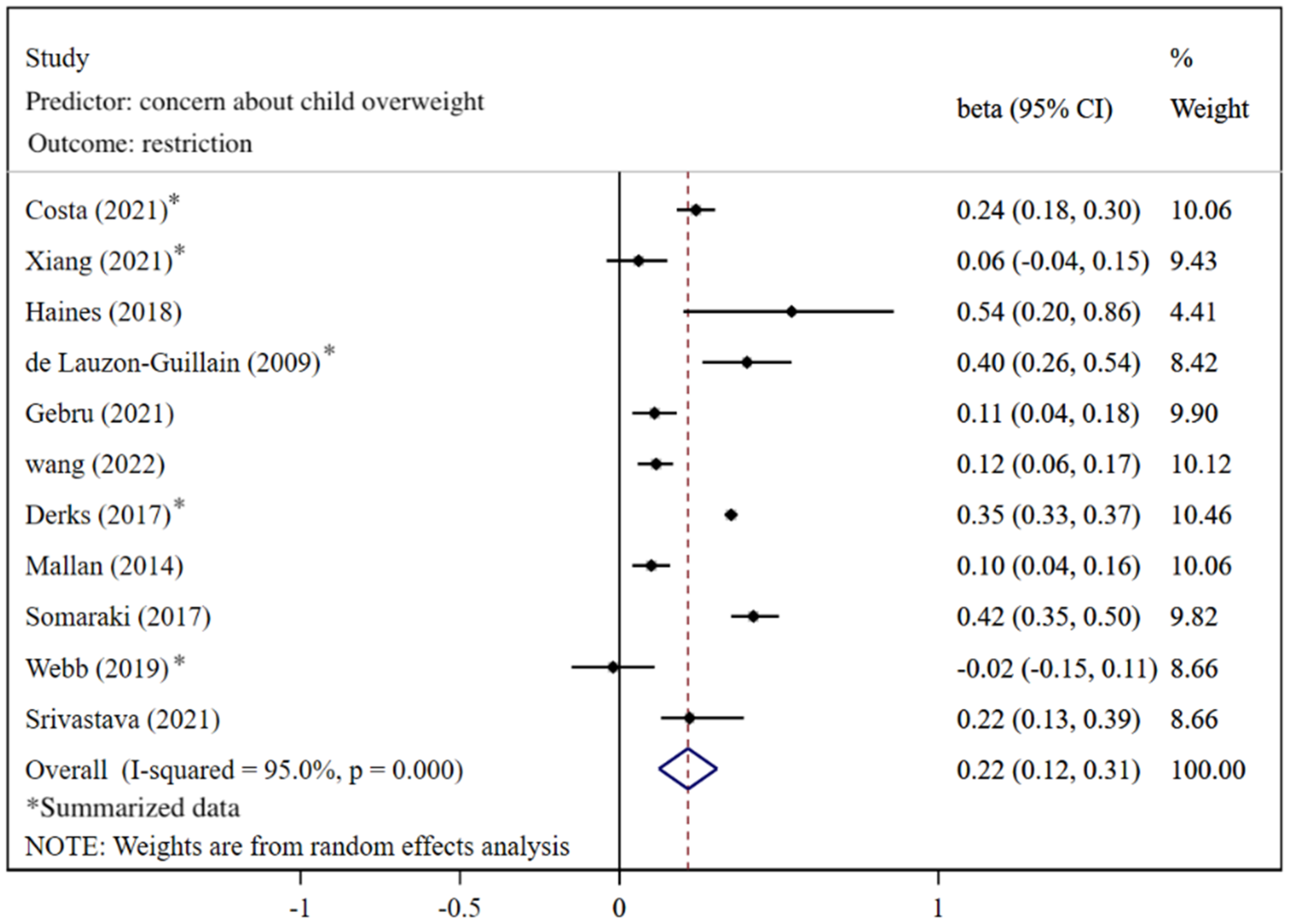

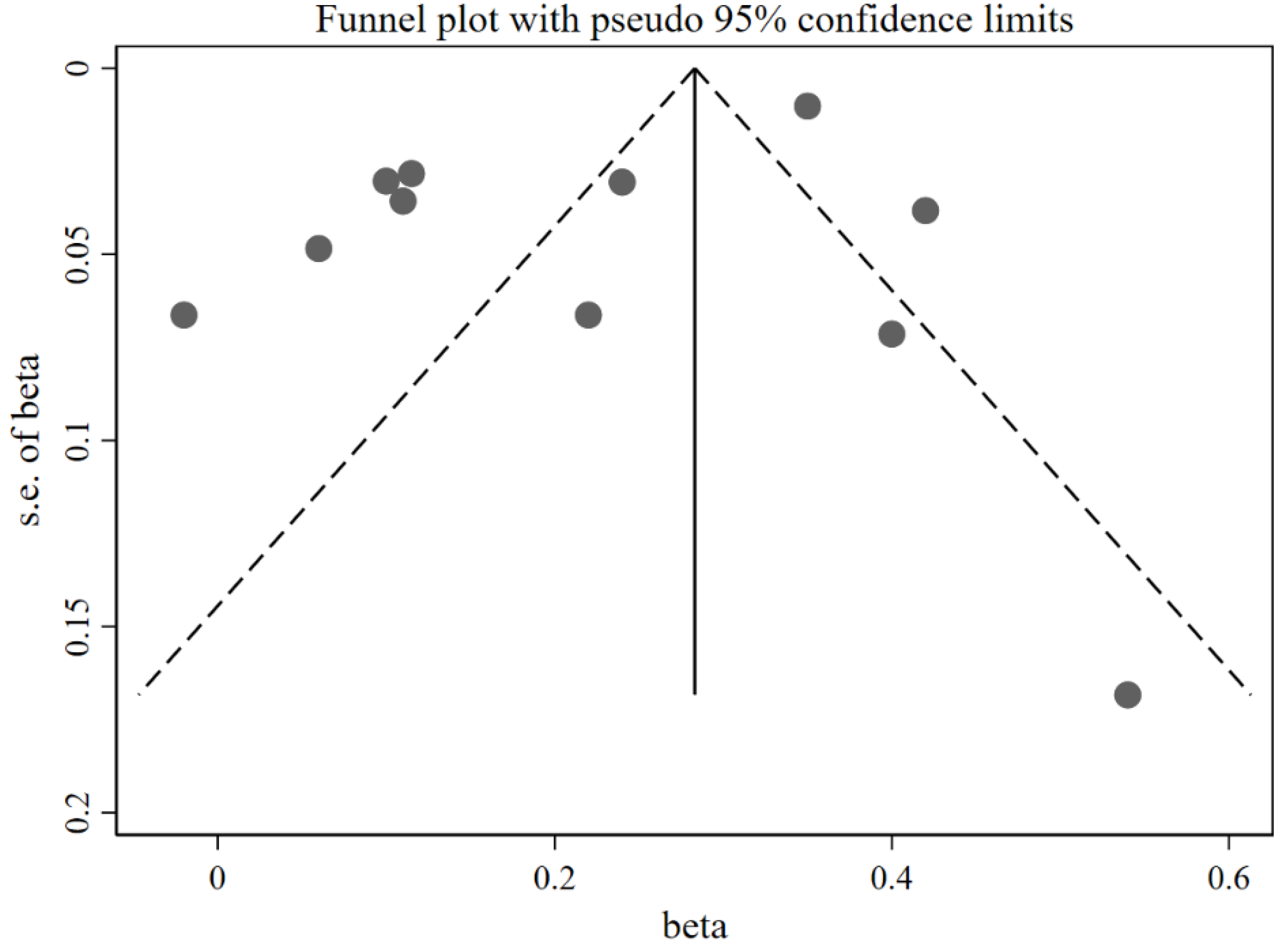

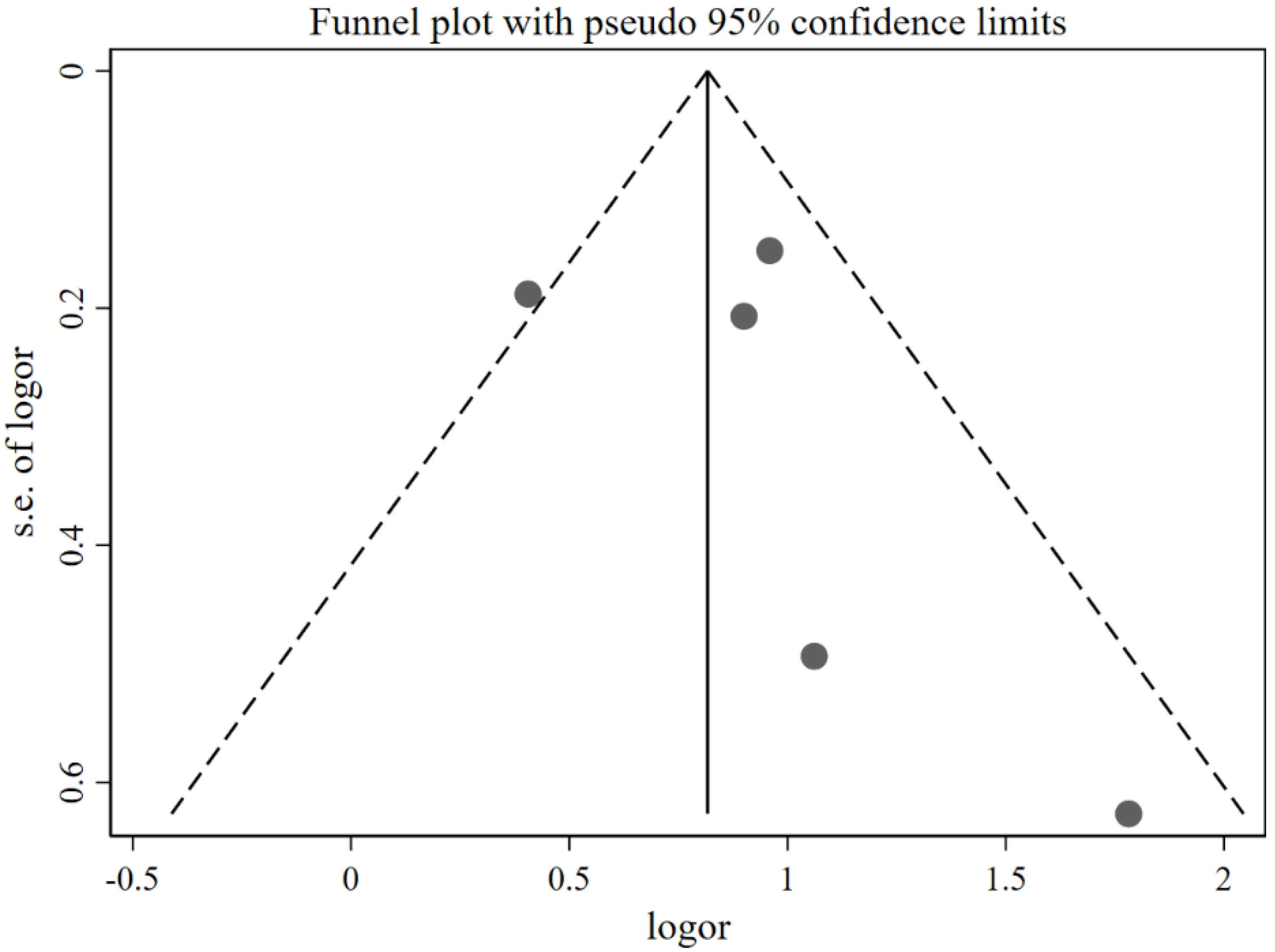

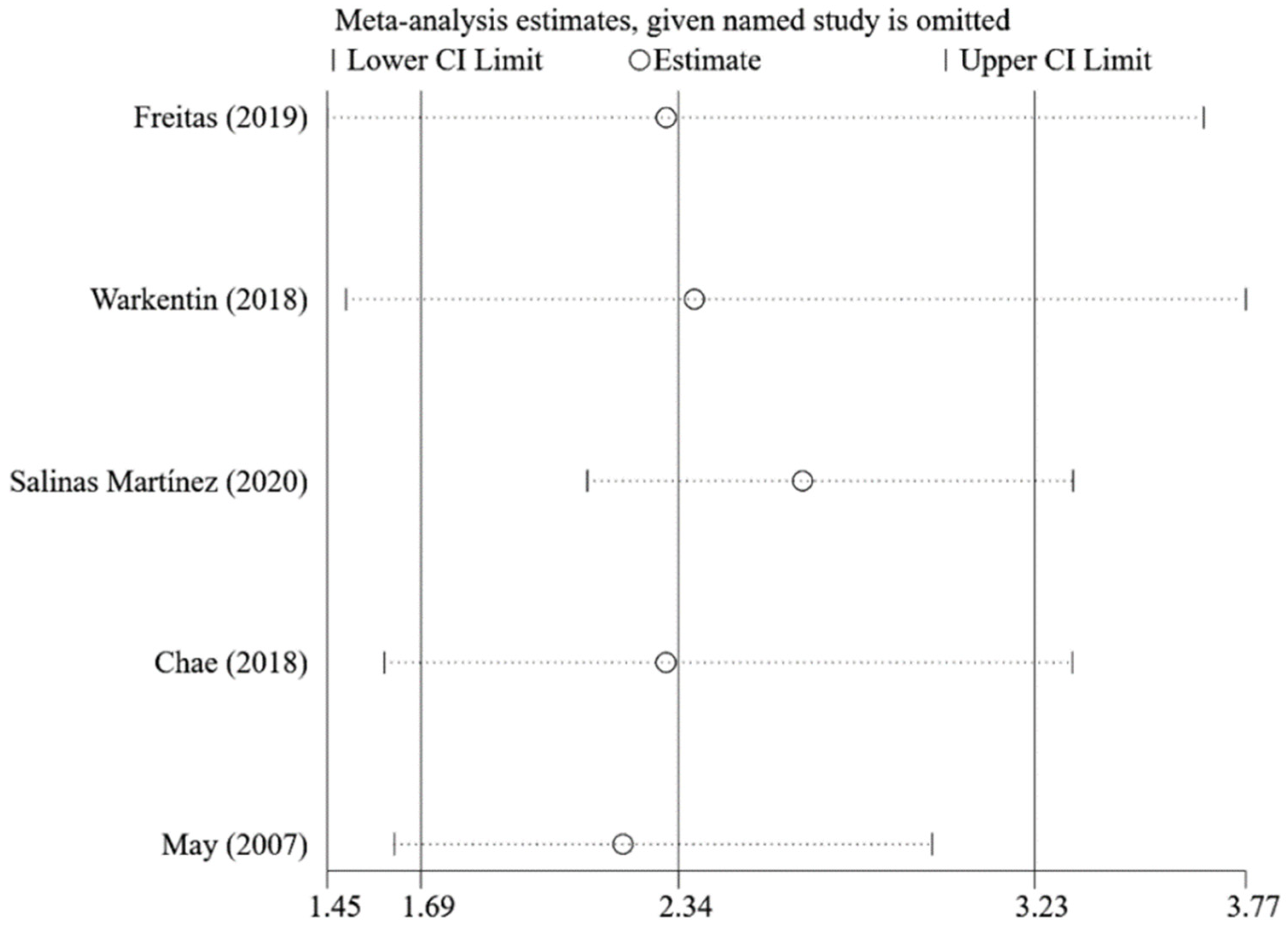

3.5.1. Concern about Child Overweight and Restrictive Feeding

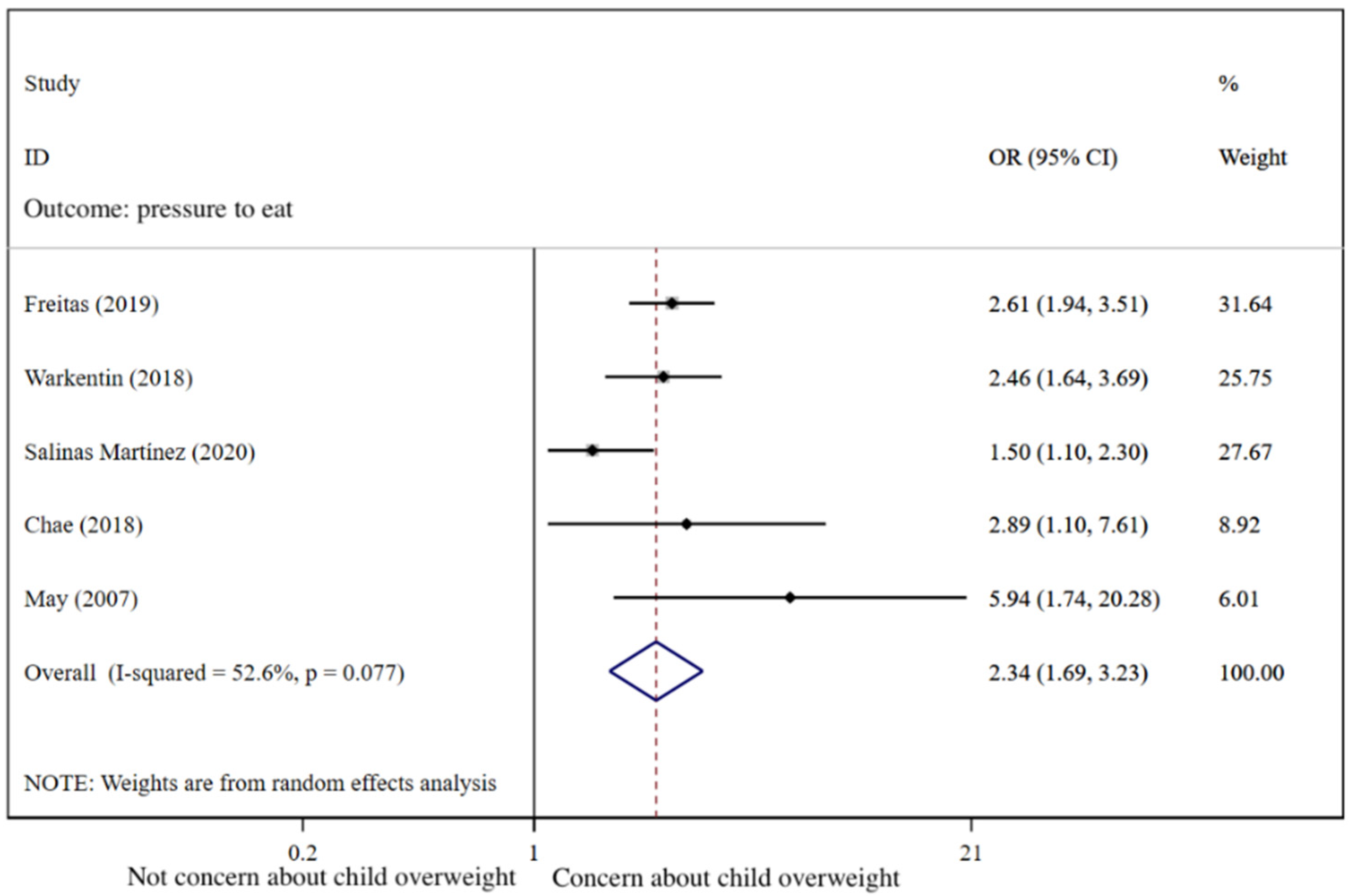

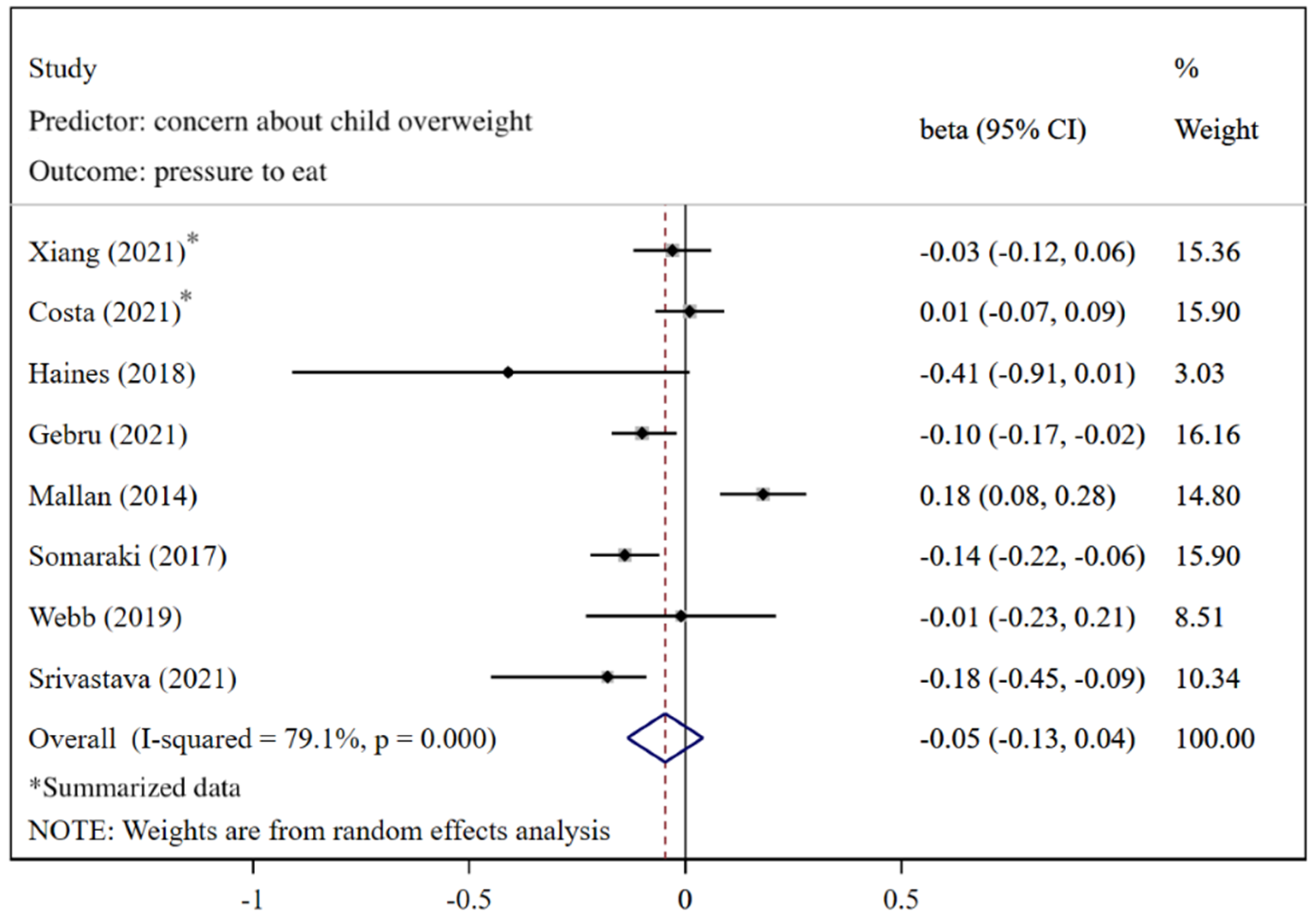

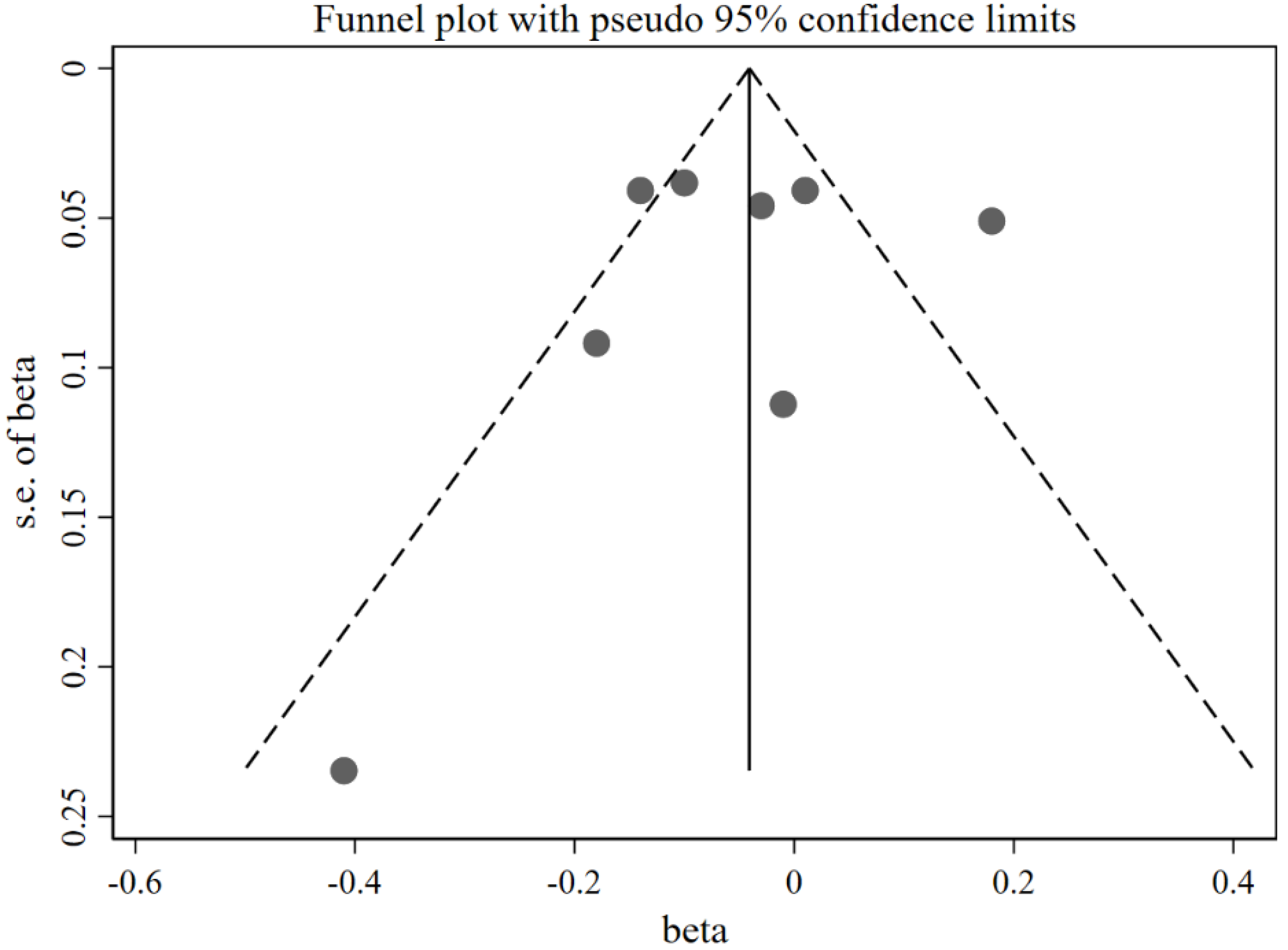

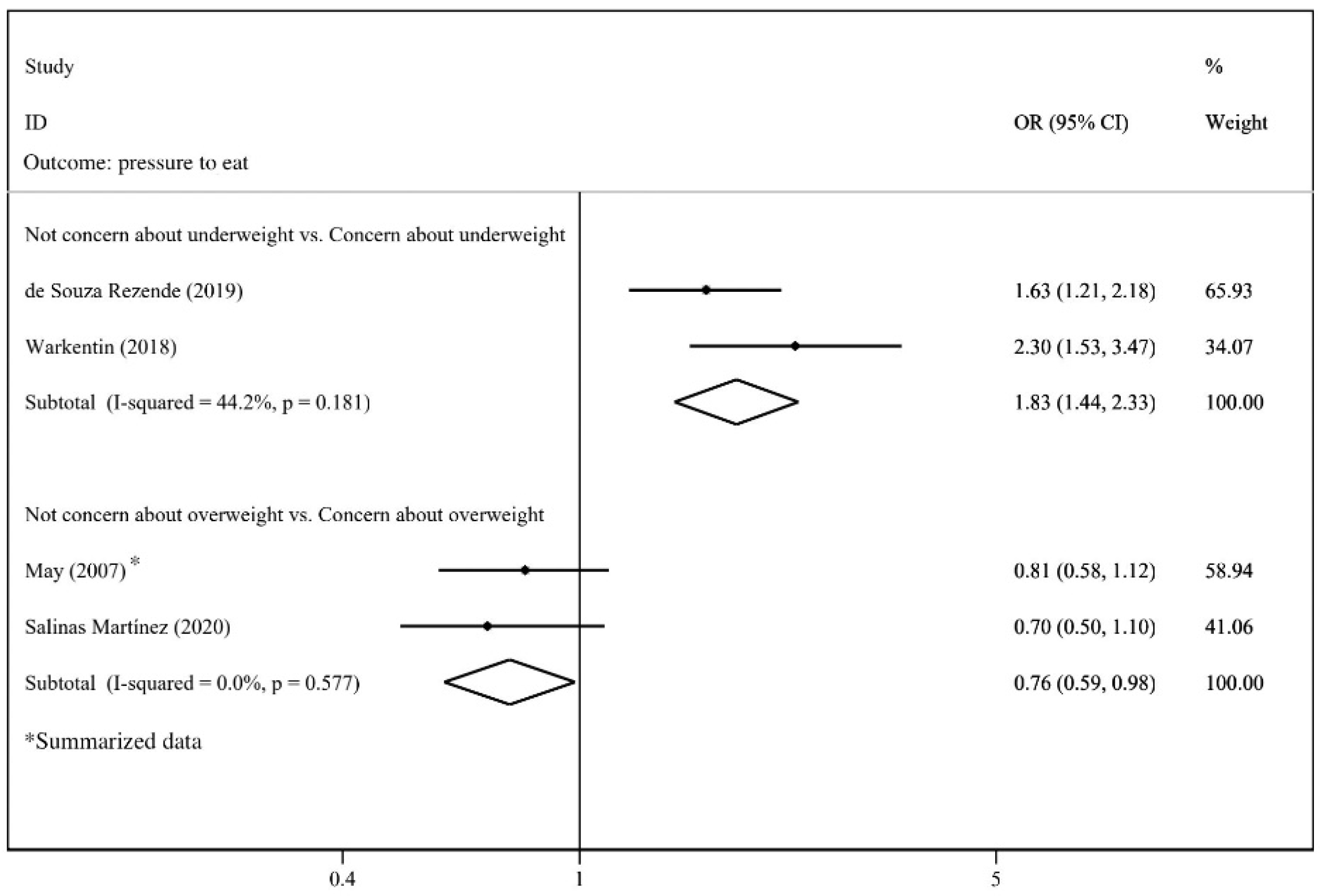

3.5.2. Concern about Child Weight and Pressure to Eat

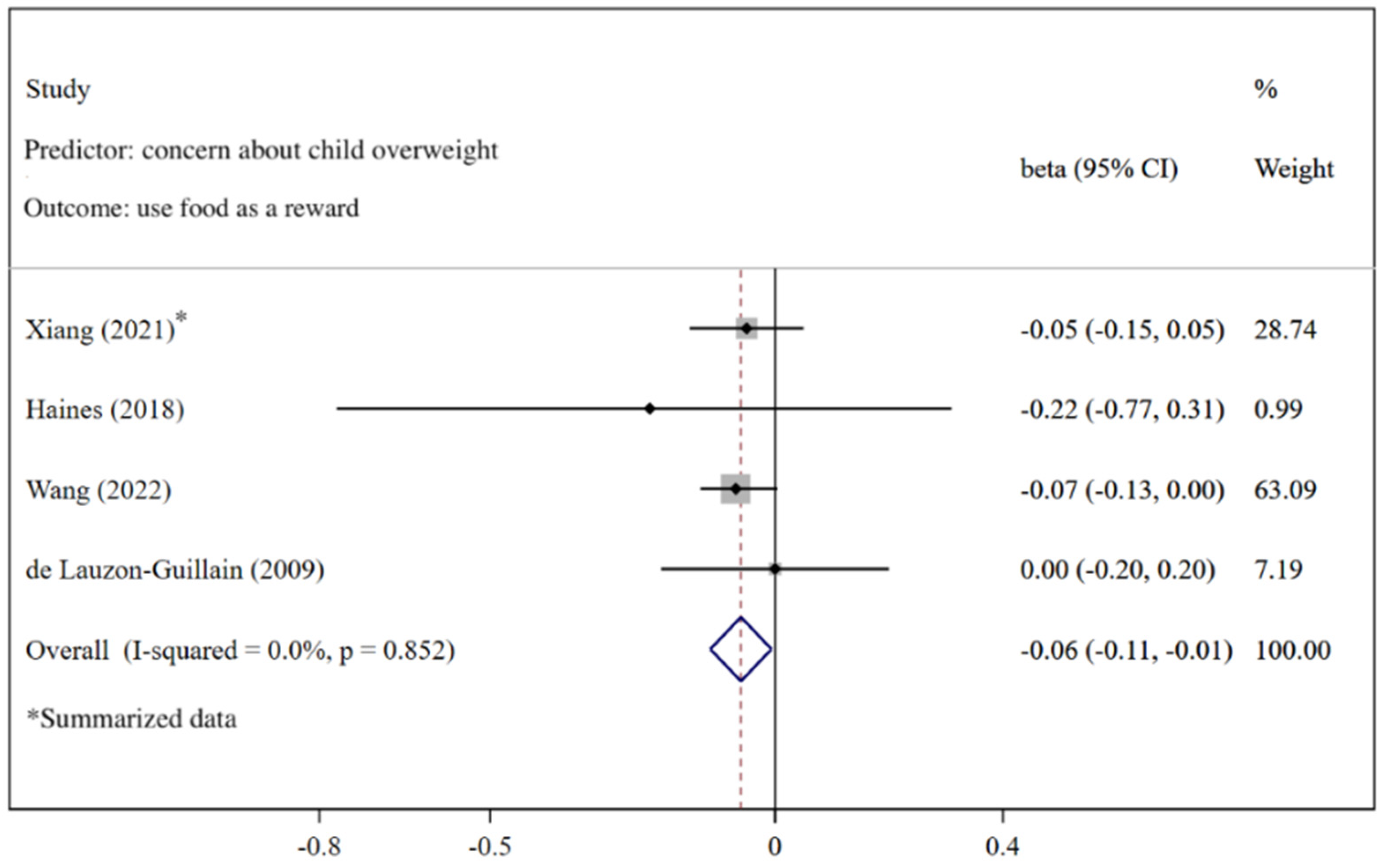

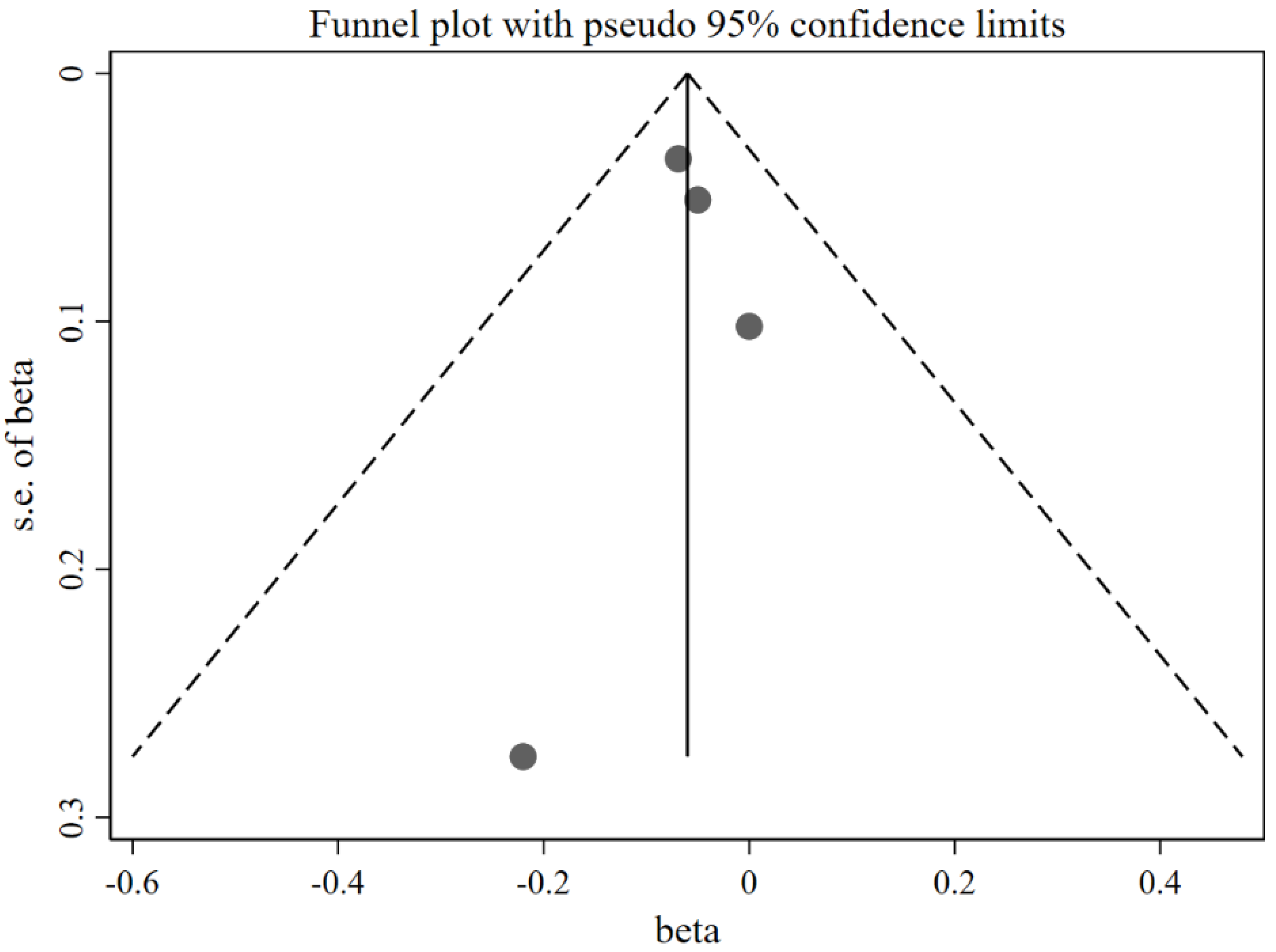

3.5.3. Concern about Child Overweight and Use of Food as a Reward

3.5.4. Subgroup Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Strengths

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Körner, A.; Kratzsch, J.; Gausche, R.; Schaab, M.; Erbs, S.; Kiess, W. New predictors of the metabolic syndrome in children—Role of adipocytokines. Pediatr. Res. 2007, 61, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gordon-Larsen, P.; Adair, L.S.; Nelson, M.C.; Popkin, B.M. Five-year obesity incidence in the transition period between adolescence and adulthood: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, T.; Smith, C.E.; Li, C.; Huang, T. Childhood BMI and Adult Type 2 Diabetes, Coronary Artery Diseases, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Cardiometabolic Traits: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Diabetes Care 2018, 41, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silventoinen, K.; Rokholm, B.; Kaprio, J.; Sørensen, T.I. The genetic and environmental influences on childhood obesity: A systematic review of twin and adoption studies. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Sacks, G.; Hall, K.D.; McPherson, K.; Finegood, D.T.; Moodie, M.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. The global obesity pandemic: Shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 2011, 378, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, F.; Sanders, M.R. The Lifestyle Behaviour Checklist: A measure of weight-related problem behaviour in obese children. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2009, 4, 266–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzicka, E.B.; Darling, K.E.; Sato, A.F. Controlling child feeding practices and child weight: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, D.A.; McBride, B.A.; Fiese, B.H.; Jones, B.L.; Cho, H. Risk factors for overweight/obesity in preschool children: An ecological approach. Child Obes. 2013, 9, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faith, M.S.; Scanlon, K.S.; Birch, L.L.; Francis, L.A.; Sherry, B. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucheron, P.; Bhopal, S.; Verma, D.; Roy, R.; Kumar, D.; Divan, G.; Kirkwood, B. Observed feeding behaviours and effects on child weight and length at 12 months of age: Findings from the SPRING cluster-randomized controlled trial in rural India. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.; Williams, K.E.; Mallan, K.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Daniels, L.A. Bidirectional associations between mothers’ feeding practices and child eating behaviours. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Savage, J.S.; Rollins, B.Y.; Kugler, K.C.; Birch, L.L.; Marini, M.E. Development of a theory-based questionnaire to assess structure and control in parent feeding (SCPF). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, C.; Li, N.; Dong, J.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Ji, C.; Wang, X.; Chi, X.; Guo, X.; Tong, M.; et al. Association between maternal nonresponsive feeding practice and child’s eating behavior and weight status: Children aged 1 to 6 years. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017, 176, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughn, A.E.; Ward, D.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Faith, M.S.; Hughes, S.O.; Kremers, S.P.; Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; O’Connor, T.M.; Patrick, H.; Power, T.G. Fundamental constructs in food parenting practices: A content map to guide future research. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 74, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beckers, D.; Karssen, L.T.; Vink, J.M.; Burk, W.J.; Larsen, J.K. Food parenting practices and children’s weight outcomes: A systematic review of prospective studies. Appetite 2021, 158, 105010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, M.; Crow, S. Targeting parents exclusively in the treatment of childhood obesity: Long-term results. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.N.; Tapper, K.; Murphy, S. Feeding goals sought by mothers of 3-5-year-old children. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15 Pt 1, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Markey, C.N.; Sawyer, R.; Johnson, S.L. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Feeding Questionnaire: A measure of parental attitudes, beliefs and practices about child feeding and obesity proneness. Appetite 2001, 36, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, P.R.; Woody, E.Z. Domain-specific parenting styles and their impact on the child’s development of particular deviance: The example of obesity proneness. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1985, 3, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, D.; Zheng, L.R.; Dev, D.A. Examining correlates of feeding practices among parents of preschoolers. Nutr. Health 2021, 2601060211032886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somaraki, M.; Eli, K.; Ek, A.; Lindberg, L.; Nyman, J.; Marcus, C.; Flodmark, C.E.; Pietrobelli, A.; Faith, M.S.; Sorjonen, K.; et al. Controlling feeding practices and maternal migrant background: An analysis of a multicultural sample. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costa, A.; Hetherington, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Maternal perception, concern and dissatisfaction with child weight and their association with feeding practices in the Generation XXI birth cohort. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 127, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, L.A.; Hofer, S.M.; Birch, L.L. Predictors of maternal child-feeding style: Maternal and child characteristics. Appetite 2001, 37, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jani Mehta, R.; Mallan, K.M.; Mihrshahi, S.; Mandalika, S.; Daniels, L.A. An exploratory study of associations between Australian- Indian mothers’ use of controlling feeding practices, concerns and perceptions of children’s weight and children’s picky eating. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 71, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, H.J.; Haycraft, E. Parental body dissatisfaction and controlling child feeding practices: A prospective study of Australian parent-child dyads. Eat. Behav. 2019, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, J.; Downing, K.L.; Tang, L.; Campbell, K.J.; Hesketh, K.D. Associations between maternal concern about child’s weight and related behaviours and maternal weight-related parenting practices: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mais, L.A.; Warkentin, S.; Latorre, M.D.; Carnell, S.; Taddei, J.A. Parental Feeding Practices among Brazilian School-Aged Children: Associations with Parent and Child Characteristics. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gebru, N.W.; Gebreyesus, S.H.; Habtemariam, E.; Yirgu, R.; Abebe, D.S. Caregivers’ feeding practices in Ethiopia: Association with caregiver and child characteristics. J. Nutr. Sci. 2021, 10, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warkentin, S.; Mais, L.A.; Latorre, M.; Carnell, S.; de Aguiar CarrazedoTaddei, J.A. Relationships between parent feeding behaviors and parent and child characteristics in Brazilian preschoolers: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D.; Moher, D.; Becker, B.J.; Sipe, T.A.; Thacker, S.B. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000, 283, 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.L.; Whaley, P.; Thayer, K.A.; Schünemann, H.J. Identifying the PECO: A framework for formulating good questions to explore the association of environmental and other exposures with health outcomes. Environ. Int. 2018, 121 Pt 1, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Child Development. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/index.html (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J.; Skinner, E.A. Review: The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2010, 35, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montroy, J.J.; Bowles, R.P.; Skibbe, L.E.; McClelland, M.M.; Morrison, F.J. The development of self-regulation across early childhood. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1744–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, V.K.; Ford-Jones, E.L. Spotlight on middle childhood: Rejuvenating the ‘forgotten years’. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musher-Eizenman, D.R.; Goodman, L.; Roberts, L.; Marx, J.; Taylor, M.; Hoffmann, D. An examination of food parenting practices: Structure, control and autonomy promotion. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 814–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, R.; Rivolta, A. A Conceptual Analysis of Food Parenting Practices in the Light of Self-Determination Theory: Relatedness-Enhancing, Competence-Enhancing and Autonomy-Enhancing Food Parenting Practices. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Connor, T.M.; Mâsse, L.C.; Tu, A.W.; Watts, A.W.; Hughes, S.O.; Beauchamp, M.R.; Baranowski, T.; Pham, T.; Berge, J.M.; Fiese, B. Food parenting practices for 5 to 12 year old children: A concept map analysis of parenting and nutrition experts input. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Paxton, S.J.; Massey, R.; Campbell, K.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Gibbons, K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: A prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arlinghaus, K.R.; Hernandez, D.C.; Eagleton, S.G.; Chen, T.A.; Power, T.G.; Hughes, S.O. Exploratory factor analysis of The Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire (CFPQ) in a low-income hispanic sample of preschool aged children. Appetite 2019, 140, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, T.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Yang, X.; Hu, M.; Yu, L.; Yu, L.; Jiang, X.; et al. Development and Preliminary Evaluation of Chinese Preschoolers’ Caregivers’ Feeding Behavior Scale. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, 1890–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, E.; Williams, K.E.; Mallan, K.M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Daniels, L.A. The Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire (FPSQ-28): A parsimonious version validated for longitudinal use from 2 to 5 years. Appetite 2016, 100, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidwell, K.M.; Tomaso, C.; Lundahl, A.; Nelson, T.D. Confirmatory factor analysis of the parental feeding style questionnaire with a preschool sample. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. JBI Critical Appraisal Tools Adelaide; Joanna Briggs Institut: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Collins, C.; Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T. A systematic review investigating associations between parenting style and child feeding behaviours. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.Q.; Norman, I.J.; While, A.E. The relationship between doctors’ and nurses’ own weight status and their weight management practices: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, B.; Wu, R.; Chang, Y.S.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, D. Bidirectional Associations between Parental Non-Responsive Feeding Practices and Child Eating Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Rezende, P.; Bellotto de Moraes, D.E.; Mais, L.A.; Warkentin, S.; Augusto de Aguiar Carrazedo Taddei, J. Maternal pressure to eat: Associations with maternal and child characteristics among 2-to 8-year-olds in Brazil. Appetite 2019, 133, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Schneider, M.; Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997, 315, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

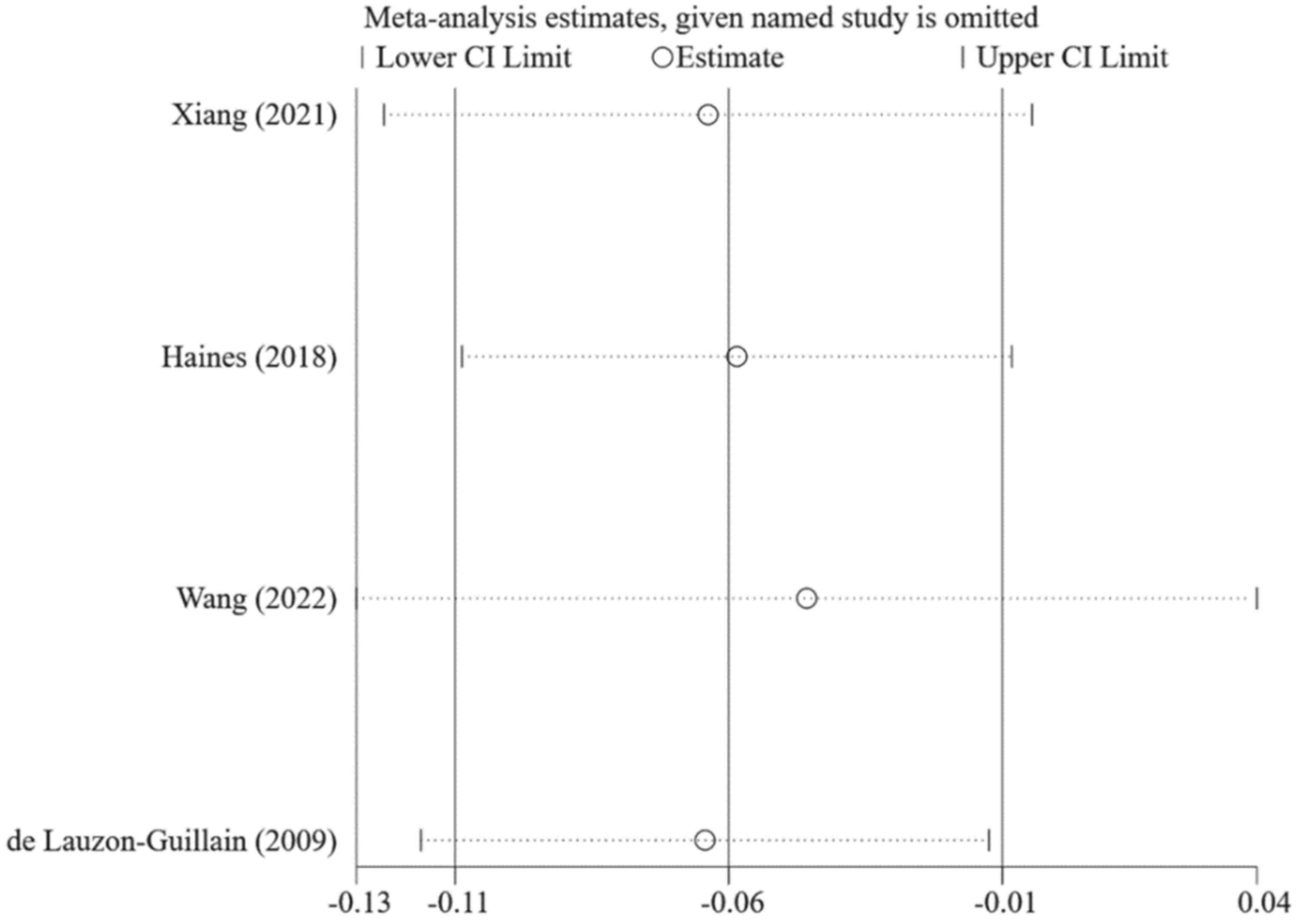

- Tobias, A. Assessing the influence of a single study in the meta-analysis estimate. Stata Tech. Bull. 1999, 8, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, K.; Cheung, C.; Lee, A.; Keung, V.; Tam, W. Associated Demographic Factors of Instrumental and Emotional Feeding in Parents of Hong Kong Children. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, C.G.; Haszard, J.J.; Taylor, R.W.; Heath, A.M.; Taylor, B.; Campbell, K.J. Parental feeding practices associated with children’s eating and weight: What are parents of toddlers and preschool children doing? Appetite 2018, 128, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichler, J.; Schmidt, R.; Poulain, T.; Hiemisch, A.; Kiess, W.; Hilbert, A. Stability, Continuity, and Bi-Directional Associations of Parental Feeding Practices and Standardized Child Body Mass Index in Children from 2 to 12 Years of Age. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haycraft, E.L.; Blissett, J.M. Maternal and paternal controlling feeding practices: Reliability and relationships with BMI. Obesity 2008, 16, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moreira, I.; Severo, M.; Oliveira, A.; Durão, C.; Moreira, P.; Barros, H.; Lopes, C. Social and health behavioural determinants of maternal child-feeding patterns in preschool-aged children. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.Y.; Burrows, T.; MacDonald-Wicks, L.; Williams, L.T.; Collins, C.E.; Chee, W.S.S. Parent-child feeding practices in a developing country: Findings from the Family Diet Study. Appetite 2018, 125, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Rosenqvist, U.; Wang, H.; Greiner, T.; Lian, G.; Sarkadi, A. Influence of grandparents on eating behaviors of young children in Chinese three-generation families. Appetite 2007, 48, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Belsky, J.; Wichstrøm, L. Parental Feeding and Child Eating: An Investigation of Reciprocal Effects. Child Dev. 2016, 87, 1538–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Musher-Eizenman, D.; Holub, S. Comprehensive Feeding Practices Questionnaire: Validation of a new measure of parental feeding practices. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, J.M.; Appugliese, D.P.; Rosenblum, K.L.; Miller, A.L.; Lumeng, J.C.; Bauer, K.W. Feeding and Mealtime Correlates of Maternal Concern About Children’s Weight. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 490–496.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cachelin, F.M.; Thompson, D. Predictors of maternal child-feeding practices in an ethnically diverse sample and the relationship to child obesity. Obesity 2013, 21, 1676–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouhlal, S.; Abrams, L.R.; McBride, C.M.; Persky, S. Cognitive and affective factors linking mothers’ perceived weight history to child feeding. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 72, 1583–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brann, L.S. Child-feeding practices and child overweight perceptions of family day care providers caring for preschool-aged children. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2010, 24, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.C.; Holub, S.C. Children’s self-regulation in eating: Associations with inhibitory control and parents’ feeding behavior. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loth, K.A.; Mohamed, N.; Trofholz, A.; Tate, A.; Berge, J.M. Associations between parental perception of- and concern about-child weight and use of specific food-related parenting practices. Appetite 2021, 160, 105068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.L.; Donohue, M.; Scanlon, K.S.; Sherry, B.; Dalenius, K.; Faulkner, P.; Birch, L.L. Child-feeding strategies are associated with maternal concern about children becoming overweight, but not children’s weight status. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1167–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seburg, E.M.; Kunin-Batson, A.; Senso, M.M.; Crain, A.L.; Langer, S.L.; Sherwood, N.E. Concern about Child Weight among Parents of Children At-Risk for Obesity. Health Behav. Policy Rev. 2014, 1, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ayine, P.; Selvaraju, V.; Venkatapoorna, C.M.K.; Geetha, T. Parental Feeding Practices in Relation to Maternal Education and Childhood Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Musher-Eizenman, D.; Leporc, E.; Holub, S.; Charles, M.A. Parental feeding practices in the United States and in France: Relationships with child’s characteristics and parent’s eating behavior. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Paxton, S.J.; McLean, S.A.; Campbell, K.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Gibbons, K. Do maternal body dissatisfaction and dietary restraint predict weight gain in young pre-school children? A 1-year follow-up study. Appetite 2013, 67, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallan, K.M.; Daniels, L.A.; Nothard, M.; Nicholson, J.M.; Wilson, A.; Cameron, C.M.; Scuffham, P.A.; Thorpe, K. Dads at the dinner table. A cross-sectional study of Australian fathers’ child feeding perceptions and practices. Appetite 2014, 73, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gregory, J.E.; Paxton, S.J.; Brozovic, A.M. Pressure to eat and restriction are associated with child eating behaviours and maternal concern about child weight, but not child body mass index, in 2- to 4-year-old children. Appetite 2010, 54, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, P.; O’Dea, J.A.; Battisti, R. Child feeding practices and perceptions of childhood overweight and childhood obesity risk among mothers of preschool children. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 64, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.R.; Moraes, D.E.B.; Warkentin, S.; Mais, L.A.; Ivers, J.F.; Taddei, J. Maternal restrictive feeding practices for child weight control and associated characteristics. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ek, A.; Sorjonen, K.; Eli, K.; Lindberg, L.; Nyman, J.; Marcus, C.; Nowicka, P. Associations between Parental Concerns about Preschoolers’ Weight and Eating and Parental Feeding Practices: Results from Analyses of the Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire, the Child Feeding Questionnaire, and the Lifestyle Behavior Checklist. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eli, K.; Sorjonen, K.; Mokoena, L.; Pietrobelli, A.; Flodmark, C.E.; Faith, M.S.; Nowicka, P. Associations between maternal sense of coherence and controlling feeding practices: The importance of resilience and support in families of preschoolers. Appetite 2016, 105, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, P.; Sorjonen, K.; Pietrobelli, A.; Flodmark, C.E.; Faith, M.S. Parental feeding practices and associations with child weight status. Swedish validation of the Child Feeding Questionnaire finds parents of 4-year-olds less restrictive. Appetite 2014, 81, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yong, C.; Xi, Y.; Huo, J.; Zou, H.; Liang, J.; Jiang, Z.; Lin, Q. Association between Parents’ Perceptions of Preschool Children’s Weight, Feeding Practices and Children’s Dietary Patterns: A Cross-Sectional Study in China. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, X.; LiuZhou, Y.; Zhu, B.; Montgomery, S.; Cao, Y. Maternal perception of child weight and concern about child overweight mediates the relationship between child weight and feeding practices. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, I.P.; Tiemeier, H.; Sijbrands, E.J.; Nicholson, J.M.; Voortman, T.; Verhulst, F.C.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Jansen, P.W. Testing the direction of effects between child body composition and restrictive feeding practices: Results from a population-based cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Webber, L.; Hill, C.; Cooke, L.; Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Associations between child weight and maternal feeding styles are mediated by maternal perceptions and concerns. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Salinas Martínez, A.M.; Cordero Franco, H.F.; Estrada de León, D.B.; Medina Franco, G.E.; Guzmán de la Garza, F.J.; Núñez Rocha, G.M. Estimating and differentiating maternal feeding practices in a country ranked first in childhood obesity. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, S.-M.; Ra, J.S. Maternal Weight Control Behaviors for Preschoolers Related to Children’s Gender. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughcum, A.E.; Powers, S.W.; Johnson, S.B.; Chamberlin, L.A.; Deeks, C.M.; Jain, A.; Whitaker, R.C. Maternal feeding practices and beliefs and their relationships to overweight in early childhood. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2001, 22, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Song, D.; Chen, C.; Li, F.; Zhu, D. Reliability and validity of a Chinese version of Child Feeding Questionnaire among parents of preschoolers. Chin. J. Child Health Care 2016, 24, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar]

- Puhl, R.M.; Heuer, C.A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, S.E. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics 2007, 120 (Suppl. 4), S164–S192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, C.L.; Pesch, M.H.; Perrin, E.M.; Appugliese, D.P.; Miller, A.L.; Rosenblum, K.; Lumeng, J.C. Maternal Concern for Child Undereating. Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Afonso, L.; Lopes, C.; Severo, M.; Santos, S.; Real, H.; Durao, C.; Moreira, P.; Oliveira, A. Bidirectional association between parental child-feeding practices and body mass index at 4 and 7 y of age. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scaglioni, S.; De Cosmi, V.; Ciappolino, V.; Parazzini, F.; Brambilla, P.; Agostoni, C. Factors Influencing Children’s Eating Behaviours. Nutrients 2018, 10, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Holley, C.E.; Farrow, C.; Haycraft, E. Investigating the role of parent and child characteristics in healthy eating intervention outcomes. Appetite 2016, 105, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Birch, L.L.; McPhee, L.; Shoba, B.C.; Steinberg, L.; Krehbiel, R. “Clean up your plate”: Effects of child feeding practices on the conditioning of meal size. Learn. Motiv. 1987, 18, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.Y.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Fierman, A.H.; Au, L.Y.; Messito, M.J. Perception of Child Weight and Feeding Styles in Parents of Chinese-American Preschoolers. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2017, 19, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.W.; de Barse, L.M.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Verhulst, F.C.; Franco, O.H.; Tiemeier, H. Bi-directional associations between child fussy eating and parents’ pressure to eat: Who influences whom? Physiol. Behav. 2017, 176, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Van Hook, J.; Thompson, D.A.; Jones, S.S. A cultural understanding of Chinese immigrant mothers’ feeding practices. A qualitative study. Appetite 2015, 87, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, B.; Adab, P.; Cheng, K.K. The role of grandparents in childhood obesity in China—Evidence from a mixed methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nankumbi, J.; Muliira, J.K. Barriers to infant and child-feeding practices: A qualitative study of primary caregivers in Rural Uganda. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

| First Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Caregivers | Age of Children | Sampling Method | Sample Size | Response Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiang, 2021 [83] | China | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 4.54 ± 0.85 years | Random cluster sampling | 1616 | 100% |

| Branch, 2017 [65] | US | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 5.39 ± 0.75 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 264 | 66.50% (264/397) |

| Francis, 2001 [24] | US | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 5.4 ± 0.02 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 196 | 99.49% (196/197) |

| Freitas, 2019 [79] | Brazil | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 2–8 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 835 | 70.88% (835/1178) |

| Webber, 2010 [86] | UK | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 8.3 ± 0.63 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 213 | 52.59% 213/405 |

| Gebru, 2021 [29] | Ethiopia | Cross-sectional study | Caregivers (mother/father/grandmother and other) | 4.5 ± 0.04 years | Multi-stage random sampling | 525 | 96.86% (525/542) |

| de Souza Rezende, 2019 [50] | Brazil | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4.98 ± 1.8 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 927 | 78.69% (927/1178) |

| Mais, 2017 [28] | Brazil | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 5–9 years | Secondary data | 659 | 46.08% (659/1430) |

| Cachelin, 2013 [66] | US | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 2–11 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 425 | 75.49% (425/563) |

| Ek, 2016 [80] | Sweden | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 5.5 ± 1.0 years | Representative sample | 478 | 51.34% (478/931) |

| Derks, 2017 [85] | Netherlands | Longitudinal study (cross-sectional relationship) | Parents | 9.76 ± 0.29 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 4689 | 54.85% (4689/8548) |

| Eli, 2016 [81] | Sweden | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4.5 ± 0.4 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 876 | 29.13% (876/3007) |

| Gregory, 2010 [77] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 3.3 ± 0.84 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 183 | 100% (183/183) |

| Wang, 2022 [84] | China | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4.56 ± 1.35 years | Convenience sample | 1106 | 95.02% (1106/1164) |

| Haines, 2018 [27] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 5.0 ± 0.1 years | Random sample | 310 | 58.71% (310/528) |

| Bouhlal, 2018 [67] | US | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4–5 years | Random sample | 221 | 100% |

| de Lauzon-Guillain, 2009 [74] | US and France | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 3.7–6.8 years | Not clear | 219 | 100% |

| Srivastava, 2021 [21] | US | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 3.95 ± 0.75 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 273 | 31.67% (273/862) |

| Brann, 2010 [68] | US | Cross-sectional study | Caregivers | 4.5 ± 1.5 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 123 | 41.28% (123/298) |

| Webb, 2019 [26] | Australia | Longitudinal study | Parents | 7.6 ± 0.8 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 48 | 100% |

| Warkentin, 2018 [30] | Brazil | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 2-5 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 402 | 40.36% (402/996) |

| Tan, 2011 [69] | US | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 3–9 years (mean age 5.6 years) | Voluntary (response) sample | 63 | 100% |

| Somaraki, 2017 [22] | Sweden | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4-7 years (mean age 4.8 years) | Population sample | 1284 | 96.91% (1284/1325) |

| Salinas Martínez, 2020 [87] | Mexico | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4.0 ± 1.2 years | Consecutive selection sample | 507 | 100% |

| Rodgers, 2013 [75] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 2.03 ± 0.37 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 218 | 99.09% (218/220) |

| Loth, 2021 [70] | US | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 6.4 ± 0.8 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 149 | 149/150 (99.33%) |

| Mallan, 2014 [76] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | Fathers | 3.5 ± 0.9 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 342 | 78.44% (342/436) |

| Chae, 2018 [88] | South Korea | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 3–5 years | Convenience sample | 223 | 100% |

| Costa, 2021 [23] | Portugal | Longitudinal study (cross-sectional relationship) | Mothers | 4–7 years (4 years at the baseline) | National population sample | 3233 | 38.73% (3233/8647) |

| May, 2007 [71] | US | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 24–59 months | Voluntary (response) sample | 967 | 73.87% (967/1309) |

| Seburg, 2014 [72] | US | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 6.6 ± 1.7 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 391 | 92.87% (391/421) |

| Crouch, 2007 [78] | Australia | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 4.42 ± 1.35 years | Voluntary (response) sample | 111 | 99.11% (111/112) |

| Ayine, 2020 [73] | US | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 6–10 years (mean age 8.42 years) | Voluntary (response) sample | 169 | 100% |

| Jani Mehta, 2014 [25] | India | Cross-sectional study | Mothers | 34 ± 14 months | Convenience sample | 203 | 88.26% (203/230) |

| Nowicka, 2014 [82] | Sweden | Cross-sectional study | Parents | 4.5 ± 0.3 years | National population sample | 564 | 18.76% (564/3007) |

| First Author, Year | Concern about Child Weight → Non-Responsive Feeding Practices | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction | Pressure to Eat | Food as a Reward | Emotional Feeding | |

| Ayine, 2020 [73] | + a,1 | Φ a,1 | ||

| Francis, 2001 [24] | Φ a,2 | Φ a,2 | ||

| Freitas, 2019 [79] | + b,2 | |||

| Webber, 2010 [86] | + c,2 | Φ c,2 | ||

| Loth, 2021 [70] | + c,2 | Φ c,2 | ||

| May, 2007 [71] | + b,2 | Φ b,2 (PEA) − b,2 (PEE) Φ b,2 (PER) | ||

| Gebru, 2021 [29] | + e,2 Φ d,2 | − e,2 + d,2 | ||

| Crouch, 2007 [78] | + a,2 | |||

| de Souza Rezende, 2019 [50] | + g,1 | |||

| Jani Mehta, 2014 [25] | Φ f,1 | Φ f,1 | ||

| Salinas Martínez, 2020 [87] | + b,2 | Φ b,2 | Φ b,2 | |

| Mais, 2017 [28] | + b,2 (RFW) + b,2 (RFH) Φ g,2 (RFW) Φ g,2 (RFH) | Φ b,2 + g,2 | Φ b,2 Φ g,2 | |

| Nowicka, 2014 [82] | + a,2 | |||

| Costa, 2021 [23] | + b,2 (4 y) + b,2 (7 y) | Φ b,2 (4 y) Φ b,2 (7 y) | ||

| Wang 2022 [84] | + e,2 | − e,2 | ||

| Xiang, 2021 [83] | − b,2 (underweight children) + b,2 (normal weight children) Φ b,2 (overweight children) | Φ b,2 (underweight children) Φ b,2 (normal weight children) Φ b,2 (overweight children) | Φ b,2 (underweight children) Φ b,2 (normal weight children) Φ b,2 (overweight children) | |

| Branch, 2017 [65] | + c,2 | Φ c,2 | ||

| Cachelin, 2013 [66] | + a,2 (Hispanic model) + a,2 (White model) | |||

| Ek, 2016 [80] | + a,2 | Φ a,2 | ||

| Derks, 2017 [85] | + e,2 (model 1) + e,2 (model 2) + e,2 (model 3) | |||

| Eli, 2016 [81] | + a,2 | Φ a,2 | ||

| Gregory, 2010 [77] | + e,2 Φ d,2 | Φ e,2 + d,2 | ||

| Haines, 2018 [27] | + b,2 + g,2 | Φ b,2 + g,2 | Φ b,2 + g,2 | Φ b,2 Φ g,2 |

| Bouhlal, 2018 [67] | + a,2 | |||

| de Lauzon-Guillain, 2009 [74] | + e,2 (RFW) + e,2 (RFH) | Φ e,2 | Φ e,2 | |

| Srivastava, 2021 [21] | + a,2 | − a,2 | ||

| Brann, 2010 [68] | + a,1 | + a,1 | ||

| Webb, 2019 [26] | Φ a,2 (RFW) Φ a,2 (RFH) | Φ a,2 | ||

| Warkentin, 2018 [30] | + b,2 (RFW) Φ b,2 (RFH) Φ g,2 (RFW) Φ g,2 (RFH) | Φ b,2 + g,2 | Φ b,2 Φ g,2 | |

| Tan, 2011 [69] | + a,1 (RFW) + a,1 (RFH) | |||

| Somaraki, 2017 [22] | + a,2 | − a,2 | ||

| Rodgers, 2013 [75] | + a,2 | |||

| Mallan, 2014 [76] | + a,2 | + a,2 | ||

| Chae, 2018 [88] | + b,2 | |||

| Seburg, 2014 [72] | + a,2 | Φ a,2 | ||

| Number of significant associations | 40 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| Total number of tested associations | 52 | 34 | 11 | 4 |

| Number of articles | 34 | 24 | 6 | 3 |

| Exposure/Outcome | Eligible Studies | Effect Size | Effect Estimates (95% CI) | p Value for Heterogeneity | I2 (%) | p Value between Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern about Child Overweight/Restriction | ||||||

| Outcome measure | beta | 0.636 | ||||

| CFQ | 8 | 0.203 (0.103, 0.303) | <0.001 | 96.0 | ||

| CFPQ | 3 | 0.288 (−0.055, 0.631) | <0.001 | 91.3 | ||

| Exposure measure | 0.740 | |||||

| Two/three items | 6 | 0.201 (0.071, 0.331) | <0.001 | 96.1 | ||

| One item | 5 | 0.223 (0.109, 0.337) | <0.001 | 86.3 | ||

| Country | 0.220 | |||||

| Developed country | 9 | 0.245 (0.148, 0.342) | <0.001 | 94.2 | ||

| Developing country | 2 | 0.101 (0.053, 0.149) | 0.327 | 0.0 | ||

| Sample size | 0.978 | |||||

| <500 | 5 | 0.214 (0.062, 0.365) | <0.001 | 85.7 | ||

| ≥500 | 6 | 0.218 (0.105, 0.331) | <0.001 | 96.2 | ||

| Children’s mean age | 0.884 | |||||

| ≤5 years old | 7 | 0.193 (0.089, 0.298) | <0.001 | 90.7 | ||

| >5 years old | 2 | 0.171 (-0.192, 0.533) | <0.001 | 96.7 | ||

| Child overweight/obesity | 0.523 | |||||

| ≤20% | 4 | 0.262 (0.084, 0.439) | <0.001 | 94.3 | ||

| >20% | 2 | 0.154 (-0.022, 0.330) | 0.002 | 89.9 | ||

| Caregivers’ role | 0.268 | |||||

| Mothers (only) | 4 | 0.293 (0.137, 0.450) | <0.001 | 93.3 | ||

| Parents/grandparents/fathers | 7 | 0.174 (0.045, 0.303) | <0.001 | 95.9 | ||

| Caregivers’ education | 0.412 | |||||

| Less than half with college degree or higher | 2 | 0.104 (0.059, 0.150) | 0.831 | 0.0 | ||

| More than half with college degree or higher | 7 | 0.228 (0.090, 0.366) | <0.001 | 91.8 | ||

| Family income | 0.027 | |||||

| High-income percentage a below median level b | 3 | 0.320 (0.233, 0.408) | 0.002 | 83.8 | ||

| High-income percentage a above median level b | 3 | 0.126 (0.079, 0.172) | 0.309 | 14.9 | ||

| Concern about Child Overweight/Pressure to Eat | ||||||

| Outcome measure | beta | 0.613 | ||||

| CFQ | 6 | −0.038 (−0.132, 0.056) | <0.001 | 83.8 | ||

| CFPQ | 2 | −0.157 (−0.535, 0.221) | 0.124 | 57.7 | ||

| Exposure measure | 0.965 | |||||

| Two/three items | 5 | −0.048 (−0.182, 0.086) | <0.001 | 86.2 | ||

| One item | 3 | −0.023 (−0.112, 0.065) | 0.191 | 39.6 | ||

| Country | 0.880 | |||||

| Developed country | 7 | −0.052 (−0.158, 0.053) | <0.001 | 82.0 | ||

| Developing country | 1 | −0.030 (−0.120, 0.060) | / | / | ||

| Sample size | 0.680 | |||||

| <500 | 4 | −0.056 (−0.291, 0.179) | 0.001 | 82.1 | ||

| ≥500 | 4 | −0.066 (−0.133, 0.001) | 0.043 | 63.2 | ||

| Children’s mean age | 0.773 | |||||

| ≤5 years old | 6 | −0.067 (−0.182, 0.048) | 0.001 | 84.1 | ||

| > 5 years old | 1 | −0.010 (−0.230, 0.210) | / | / | ||

| Child overweight/obesity | 0.068 | |||||

| ≤20% | 3 | −0.123 (−0.178, −0.068) | 0.362 | 1.5 | ||

| >20% | 2 | −0.008 (−0.067, 0.052) | 0.515 | 0.0 | ||

| Caregivers’ role | 0.486 | |||||

| Mothers (only) | 3 | −0.095 (−0.244, −0.060) | <0.001 | 77.5 | ||

| Parents/grandparents/fathers | 5 | −0.022 (−0.145, 0.101) | 0.012 | 82.5 | ||

| Caregivers’ education | 0.237 | |||||

| Less than half with college degree or higher | 2 | 0.038 (−0.236, 0.312) | <0.001 | 94.8 | ||

| More than half with college degree or higher | 5 | −0.102 (−0.184, −0.021) | 0.169 | 37.8 | ||

| Family income | 0.266 | |||||

| High-income percentage a below median level b | 1 | 0.010 (−0.070, 0.090) | / | / | ||

| High-income percentage a above median level b | 2 | −0.112 (−0.181, −0.043) | 0.421 | 0.0 | ||

| Concern about Child Overweight/Reward | ||||||

| Outcome measure | beta | 0.750 | ||||

| CFQ | 2 | −0.063 (−0.119, -0.007) | 0.758 | 0.0 | ||

| CFPQ | 2 | −0.027 (−0.214, 0.161) | 0.454 | 0.0 | ||

| Country | 0.750 | |||||

| Developed country | 2 | −0.027 (−0.214, 0.161) | 0.454 | 0.0 | ||

| Developing country | 2 | −0.063 (−0.119, −0.007) | 0.758 | 0.0 | ||

| Sample size | 0.750 | |||||

| <500 | 2 | −0.027 (−0.214, 0.161) | 0.454 | 0.0 | ||

| ≥500 | 2 | −0.063 (−0.119, −0.007) | 0.758 | 0.0 | ||

| Child overweight/obesity | 0.787 | |||||

| ≤20% | 2 | −0.071 (−0.138, −0.004) | 0.587 | 0.0 | ||

| >20% | 1 | −0.050 (−0.150, 0.050) | / | / | ||

| Caregivers’ role | 0.638 | |||||

| Mothers (only) | 2 | −0.071 (−0.138, −0.004) | 0.587 | 0.0 | ||

| Parents/grandparents/fathers | 2 | −0.040 (−0.129, 0.049) | 0.661 | 0.0 | ||

| Concern about Child Overweight/Restriction | ||||||

| Outcome measure | OR | 0.413 | ||||

| CFQ | 1 | 5.940 (1.740, 20.279) | / | / | ||

| CFPQ | 2 | 2.557 (2.012, 3.249) | 0.817 | 0.0 | ||

| Exposure measure | 0.951 | |||||

| Two/three items | 1 | 2.460 (1.640, 3.690) | / | / | ||

| One item | 4 | 2.378 (1.502, 3.766) | 0.041 | 63.6 | ||

| Country | 0.289 | |||||

| Developed country | 2 | 3.808 (1.781, 8.142) | 0.366 | 0.0 | ||

| Developing country | 3 | 2.141 (1.515, 3.027) | 0.058 | 64.9 | ||

| Sample size | 0.786 | |||||

| <500 | 2 | 2.337 (1.347, 4.055) | 0.763 | 0.0 | ||

| ≥500 | 3 | 2.520 (1.734, 3.663) | 0.019 | 74.7 | ||

| Child overweight/obesity | 0.656 | |||||

| ≤20% | 1 | 2.89 (1.098, 7.604) | / | / | ||

| >20% | 3 | 2.141 (1.515, 3.027) | 0.058 | 64.9 | ||

| Caregivers’ role | 0.951 | |||||

| Mothers (only) | 4 | 2.378 (1.502, 3.766) | 0.041 | 63.6 | ||

| Parents/grandparents/fathers | 1 | 2.460 (1.640, 3.690) | / | / | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Chang, Y.-S.; Hiyoshi, A.; Winkley, K.; Cao, Y. The Relationships between Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142885

Wang J, Wei X, Chang Y-S, Hiyoshi A, Winkley K, Cao Y. The Relationships between Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2022; 14(14):2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142885

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jian, Xiaoxue Wei, Yan-Shing Chang, Ayako Hiyoshi, Kirsty Winkley, and Yang Cao. 2022. "The Relationships between Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Nutrients 14, no. 14: 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142885

APA StyleWang, J., Wei, X., Chang, Y.-S., Hiyoshi, A., Winkley, K., & Cao, Y. (2022). The Relationships between Caregivers’ Concern about Child Weight and Their Non-Responsive Feeding Practices: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 14(14), 2885. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14142885