Nature and Potential Impact of Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

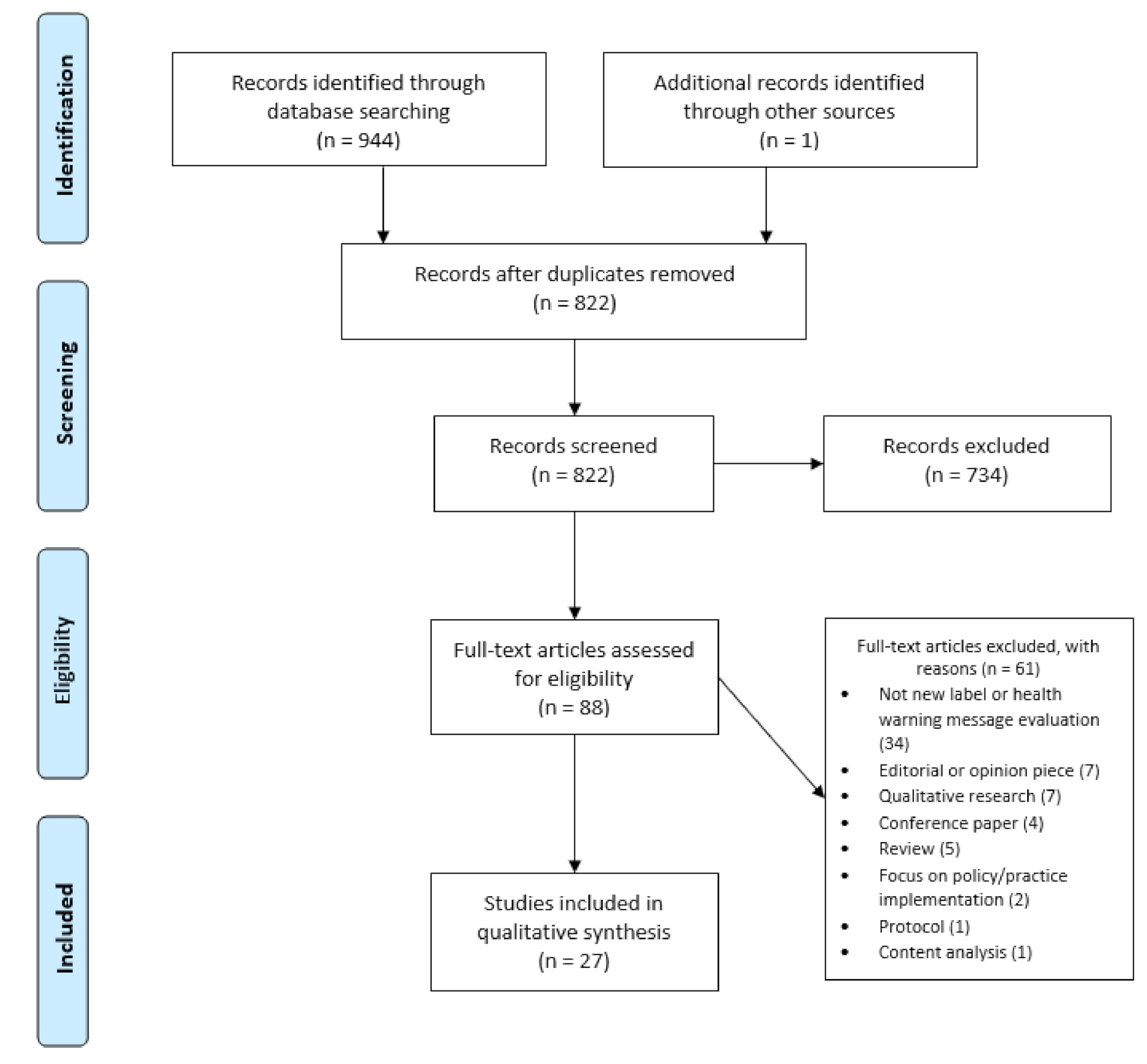

2.4. Study Selection and Summary

3. Results

3.1. Research Scope

3.2. Key Label Characteristics—Impact on the Outcomes

3.2.1. Label Effectiveness

3.2.2. Label Content—Image vs. Text

3.2.3. Label Content—Message Characteristics

3.2.4. Label Format

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Shield, K.; Manthey, J.; Rylett, M.; Probst, C.; Wettlaufer, A.; Parry, C.D.H.; Rehm, J. National, regional, and global burdens of disease from 2000 to 2016 attributable to alcohol use: A comparative risk assessment study. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e51–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okaru, A.O.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Margin of exposure analyses and overall toxic effects of alcohol with special consideration of carcinogenicity. Nutrients 2021, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm, J.; Gmel Sr, G.E.; Gmel, G.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Imtiaz, S.; Popova, S.; Probst, C.; Roerecke, M.; Room, R.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol use and the burden of disease—An update. Addiction 2017, 112, 968–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, J.; Taylor, B.; Mohapatra, S.; Irving, H.; Baliunas, D.; Patra, J.; Roerecke, M. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010, 29, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnardi, V.; Rota, M.; Botteri, E.; Tramacere, I.; Islami, F.; Fedirko, V.; Scotti, L.; Jenab, M.; Turati, F.; Pasquali, E.; et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: A comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Volume 96: Alcohol Consumption and Ethyl Carbamate; International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC: Lion, France, 2010; Volume 96. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Alcohol Drinking; International Agency for Research on Cancer IARC: Lion, France, 1988; Volume 44. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, B.F.; Goldstein, R.; Saha, T.D.; Chou, S.P.; Jung, J.; Zhang, H.; Pickering, R.P.; Ruan, W.J.; Smith, S.M.; Huang, B.; et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehm, J.; Roerecke, M. Cardiovascular effects of alcohol consumption. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2017, 27, 534–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, S.; Shield, K.D.; Roerecke, M.; Samokhvalov, A.V.; Lonnroth, K.; Rehm, J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for tuberculosis: Meta-analyses and burden of disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellos, S.; Skapinakis, P.; Rai, D.; Zitko, P.; Araya, R.; Lewis, G.; Lionis, C.; Mavreas, V. Longitudinal association between different levels of alcohol consumption and a new onset of depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Results from an international study in primary care. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.M.; Fergusson, D.M. Alcohol and depression. Addiction 2011, 106, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, S.; Lange, S.; Shield, K.; Mihic, A.; Chudley, A.E.; Mukherjee, R.A.S.; Bekmuradov, D.; Rehm, J. Comorbidity of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 387, 978–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, M.; Quigley, B.M.; Eiden, R. The Effects of Prenatal Alcohol Exposure on Infant Mental Development: A Meta-Analytical Review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003, 38, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheideler, J.K.; Klein, W.M.P. Awareness of the Link between Alcohol Consumption and Cancer across the World: A Review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2018, 27, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Shokar, S.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Hammond, D.; Greenfield, T.K.; McGavock, J.; Weerasinghe, A.; Hobin, E. Baseline Assessment of Alcohol-Related Knowledge of and Support for Alcohol Warning Labels Among Alcohol Consumers in Northern Canada and Associations With Key Sociodemographic Characteristics. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvert, C.M.; Toomey, T.; Jones-Webb, R. Are people aware of the link between alcohol and different types of Cancer? BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, K.L.; Christensen, A.S.P.; Meyer, M.K.H. Awareness of alcohol as a risk factor for cancer: A population-based cross-sectional study among 3000 Danish men and women. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020, 19, 101156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Moreno, J.M.; Harris, M.E.; Breda, J.; Møller, L.; Alfonso-Sanchez, J.L.; Gorgojo, L. Enhanced labelling on alcoholic drinks: Reviewing the evidence to guide alcohol policy. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 23, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH). Available online: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.gisah.A1191?lang=en&showonly=GISAH (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Government of Canada Labelling Requirements for Alcoholic Beverages. Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/food-label-requirements/labelling/industry/alcohol/eng/1392909001375/1392909133296 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- European Commission Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011R1169 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Food Standards Australia and New Zealand Labelling of Alcoholic Beverages. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/consumer/labelling/Pages/Labelling-of-alcoholic-beverages.aspx (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Labeling Resources. Available online: https://www.ttb.gov/labeling/labeling-resources (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Maynard, O.M.; Langfield, T.; Attwood, A.S.; Allen, E.; Drew, I.; Votier, A.; Munafò, M.R. No Impact of Calorie or Unit Information on Ad Libitum Alcohol Consumption (Special Issue: Communicating messages about drinking). Alcohol Alcohol. 2018, 53, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maynard, O.; Blackwell, A.; Munafò, M.; Attwood, A. Know Your Limits: Labelling Interventions to Reduce Alcohol Consumption; Alcohol Research UK: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Croker, H.; Packer, J.; Russell, S.J.; Stansfield, C.; Viner, R.M. Front of pack nutritional labelling schemes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent evidence relating to objectively measured consumption and purchasing. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 33, 518–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.; Jewell, J. What Is the Evidence on the Policy Specifications, Development Processes and Effectiveness of Existing Front-of-Pack Food Labelling Policies in the WHO European Region? WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.; Allsop, S.; Cail, D.; Chikritzhs, T.; Daube, M.; Kirby, G.; Mattick, R. Alcohol Warning Labels: Evidence of Effectiveness on Risky Alcohol Consumption and Short Term Outcomes; National Drug Research Institute: Bentley, WA, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.; Room, R. Warnings on alcohol containers and advertisements: International experience and evidence on effects. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossou, G.; Gallopel-Morvan, K.; Diouf, J.-F. The effectiveness of current French health warnings displayed on alcohol advertisements and alcoholic beverages. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A.; Toutain, S.; Hill, C.; Simmat-Durand, L. Warning about drinking during pregnancy: Lessons from the French experience. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coomber, K.; Martino, F.; Barbour, I.R.; Mayshak, R.; Miller, P.G. Do consumers “Get the facts”? A survey of alcohol warning label recognition in Australia. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critchlow, N.; Jones, D.; Moodie, C.; Mackintosh, A.M.; Fitzgerald, N.; Hooper, L.; Thomas, C.; Vohra, J. Awareness of product-related information, health messages and warnings on alcohol packaging among adolescents: A cross-sectional survey in the United Kingdom. J. Public Health 2020, 42, e223–e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kersbergen, I.; Field, M. Alcohol consumers’ attention to warning labels and brand information on alcohol packaging: Findings from cross-sectional and experimental studies. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M.; Francis, D.B.; Bridges, C.; Sontag, J.M.; Ribisl, K.M.; Brewer, N.T. The impact of strengthening cigarette pack warnings: Systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 164, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noar, S.M.; Francis, D.B.; Bridges, C.; Sontag, J.M.; Brewer, N.T.; Ribisl, K.M. Effects of Strengthening Cigarette Pack Warnings on Attention and Message Processing: A Systematic Review. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2017, 94, 416–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamdani, M. The case for stringent alcohol warning labels: Lessons from the tobacco control experience. J. Public Health Policy 2013, 35, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, S.; Holmes, J.; Gavens, L.; De Matos, E.G.; Li, J.; Ward, B.; Hooper, L.; Dixon, S.; Buykx, P. Awareness of alcohol as a risk factor for cancer is associated with public support for alcohol policies. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buykx, P.; Gilligan, C.; Ward, B.; Kippen, R.; Chapman, K. Public support for alcohol policies associated with knowledge of cancer risk. Int. J. Drug Policy 2015, 26, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcohol Action Ireland What is Public Health Alcohol Act? Available online: https://alcoholireland.ie/what-is-the-public-health-alcohol-bill/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E. A systematic review of the efficacy of alcohol warning labels: Insights from qualitative and quantitative research in the new millennium. J. Soc. Mark. 2018, 8, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Pechey, E.; Kosīte, D.; König, L.M.; Mantzari, E.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J. Impact of health warning labels on selection and consumption of food and alcohol products: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2020, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimova, E.D.; Mitchell, D. Rapid literature review on the impact of health messaging and product information on alcohol labelling. Drugs: Educ. Prev. Policy 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wettlaufer, A. Can a Label Help me Drink in Moderation? A Review of the Evidence on Standard Drink Labelling. Subst. Use Misuse 2018, 53, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, C.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Parkinson, J.; Li, S. Alcohol Warning Label Awareness and Attention: A Multi-method Study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017, 53, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, E.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Weerasinghe, A.; Vallance, K.; Hammond, D.; Greenfield, T.K.; McGavock, J.; Paradis, C.; Stockwell, T. Effects of strengthening alcohol labels on attention, message processing, and perceived effectiveness: A quasi-experimental study in Yukon, Canada. Int. J. Drug Policy 2020, 77, 102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, E.; Weerasinghe, A.; Vallance, K.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Paradis, C.; Stockwell, T. Testing Alcohol Labels as a Tool to Communicate Cancer Risk to Drinkers: A Real-World Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T.; Vallance, K.; Hobin, E. The Effects of Alcohol Warning Labels on Population Alcohol Consumption: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis of Alcohol Sales in Yukon, Canada. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobin, E.; Shokar, S.; Vallance, K.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Paradis, C.; Stockwell, T. Communicating risks to drinkers: Testing alcohol labels with a cancer warning and national drinking guidelines in Canada. Can. J. Public Health 2020, 111, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, N.; Pechey, E.; Mantzari, E.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; De Loyde, K.; Morris, R.W.; Munafò, M.R.; Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J. Impact of health warning labels communicating the risk of cancer on alcohol selection: An online experimental study. Addiction 2021, 116, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; De Loyde, K.; Pechey, E.; Hobson, A.; Pilling, M.; Morris, R.W.; Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J. Health warning labels and alcohol selection: A randomised controlled experiment in a naturalistic shopping laboratory. Addiction 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechey, E.; Clarke, N.; Mantzari, E.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; Deloyde, K.; Morris, R.W.; Marteau, T.M.; Hollands, G.J. Image-and-text health warning labels on alcohol and food: Potential effectiveness and acceptability. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongenelis, M.; Pettigrew, S.; Wakefield, M.; Slevin, T.; Pratt, I.S.; Chikritzhs, T.; Liang, W. Investigating Single-Versus Multiple-Source Approaches to Communicating Health Messages Via an Online Simulation. Am. J. Health Promot. 2018, 32, 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongenelis, M.I.; Pratt, I.S.; Slevin, T.; Chikritzhs, T.; Liang, W.; Pettigrew, S. The effect of chronic disease warning statements on alcohol-related health beliefs and consumption intentions among at-risk drinkers. Health Educ. Res. 2018, 33, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettigrew, S.; Jongenelis, M.I.; Glance, D.; Chikritzhs, T.; Pratt, I.S.; Slevin, T.; Liang, W.; Wakefield, M. The effect of cancer warning statements on alcohol consumption intentions. Health Educ. Res. 2016, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigg, S.; Stafford, L.D. Health Warnings on Alcoholic Beverages: Perceptions of the Health Risks and Intentions towards Alcohol Consumption. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, L.D.; Salmon, J. Alcohol health warnings can influence the speed of consumption. J. Public Health 2017, 25, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, N.; Egan, M.; Londakova, K.; Mottershaw, A.; Harper, H.; Burton, R.; Henn, C.; Smolar, M.; Walmsley, M.; Arambepola, R.; et al. Effect of alcohol label designs with different pictorial representations of alcohol content and health warnings on knowledge and understanding of low-risk drinking guidelines: A randomized controlled trial. Addiction 2021, 116, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamdani, M.; Smith, S. Alcohol warning label perceptions: Emerging evidence for alcohol policy. Can. J. Public Health 2015, 106, e395–e400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.G.; Grummon, A.H.; Lazard, A.J.; Maynard, O.M.; Taillie, L.S. Reactions to graphic and text health warnings for cigarettes, sugar-sweetened beverages, and alcohol: An online randomized experiment of US adults. Prev. Med. 2020, 137, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monk, R.L.; Westwood, J.; Heim, D.; Qureshi, A.W. The effect of pictorial content on attention levels and alcohol-related beliefs: An eye-tracking study. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 47, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenstern, M.; Dumbili, E.W.; Hansen, J.; Hanewinkel, R. Effects of alcohol warning labels on alcohol-related cognitions among German adolescents: A factorial experiment. Addict. Behav. 2021, 117, 106868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krischler, M.; Glock, S. Alcohol warning labels formulated as questions change alcohol-related outcome expectancies: A pilot study. Addict. Res. Theory 2015, 23, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. The Role of Narrative Pictorial Warning Labels in Communicating Alcohol-Related Cancer Risks. Health Commun. 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Agnoli, L.; Vecchio, R.; Charters, S.; Mariani, A. Health warnings on wine labels: A discrete choice analysis of Italian and French Generation Y consumers. Wine Econ. Policy 2019, 8, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, A.K.M.; Drax, K.; Attwood, A.S.; Munafò, M.R.; Maynard, O.M. Informing drinkers: Can current UK alcohol labels be improved? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 192, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glock, S.; Krolak-Schwerdt, S. Changing Outcome Expectancies, Drinking Intentions, and Implicit Attitudes toward Alcohol: A Comparison of Positive Expectancy-Related and Health-Related Alcohol Warning Labels. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2013, 5, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.G.; Grummon, A.H.; Maynard, O.M.; Kameny, M.R.; Jenson, D.; Popkin, B.M. Causal Language in Health Warning Labels and US Adults’ Perception: A Randomized Experiment. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, 1429–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, W.; Pettigrew, S. The relative influence of alcohol warning statement type on young drinkers’ stated choices. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero-Rejon, C.; Attwood, A.S.; Blackwell, A.K.M.; Ibáñez-Zapata, J.-A.; Munafò, M.R.; Maynard, O.M. Alcohol pictorial health warning labels: The impact of self-affirmation and health warning severity. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hamdani, M.; Smith, S.M. Alcohol Warning Label Perceptions: Do Warning Sizes and Plain Packaging Matter? J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2017, 78, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jané-Llopis, E.; Kokole, D.; Neufeld, M.; Hasan, O.S.M.; Rehm, J. What Is the Current Alcohol Labelling Practice in the WHO European Region and What Are Barriers and Facilitators to Development and Implementation of Alcohol Labelling Policy? Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report, No. 68. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558550/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Neufeld, M.; Ferreira-Borges, C.; Rehm, J. Implementing Health Warnings on Alcoholic Beverages: On the Leading Role of Countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 65, Available online: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/112736 (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Chisholm, D.; Moro, D.; Bertram, M.; Pretorius, C.; Gmel, G.; Shield, K.; Rehm, J. Are the “Best Buys” for Alcohol Control Still Valid? An Update on the Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Strategies at the Global Level. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2018, 79, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Status Report on Alcohol Consumption, Harm and Policy Responses in 30 European Countries 2019; WHO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D.; et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, T.; Solomon, R.; O’Brien, P.; Vallance, K.; Hobin, E. Cancer Warning Labels on Alcohol Containers: A Consumer’s Right to Know, a Government’s Responsibility to Inform, and an Industry’s Power to Thwart. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2020, 81, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petticrew, M.; Shemilt, I.; Lorenc, T.M.; Marteau, T.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; O’Mara-Eves, A.; Stautz, K.; Thomas, J. Alcohol advertising and public health: Systems perspectives versus narrow perspectives. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2017, 71, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, P.; Mitchell, A.D. On the Bottle: Health Information, Alcohol Labelling and the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement. QUT Law Rev. 2018, 18, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; Shokar, S.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Greenfield, T.; McGavock, J.; Zhao, J.; Weerasinghe, A.; Hobin, E. Testing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Alcohol Warning Labels and Modifications Resulting From Alcohol Industry Interference in Yukon, Canada: Protocol for a Quasi-Experimental Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2020, 9, e16320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weerasinghe, A.; Schoueri-Mychasiw, N.; Vallance, K.; Stockwell, T.; Hammond, D.; McGavock, J.; Greenfield, T.K.; Paradis, C.; Hobin, E. Improving Knowledge that Alcohol Can Cause Cancer is Associated with Consumer Support for Alcohol Policies: Findings from a Real-World Alcohol Labelling Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiilamo, H.; Crosbie, E.; A Glantz, S. The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: The role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tob. Control 2014, 23, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, M.L. The FCTC’s evidence-based policies remain a key to ending the tobacco epidemic. Tob. Control 2013, 22, i45–i46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Authors and Year Published | Country | Study Aim (According to Authors) | Setting | Methodology/Study Design | Sample Characteristics | Population (P) or Inclusion Criteria (IC) | Sampling and Recruitment | Year Data Collected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hamdani and Smith (2015) [64] | Canada | To apply the lessons learned from the tobacco health warnings and plain packaging literature to an alcohol packaging study and test whether labelling alters consumer perceptions. | Online (survey) | Experiment: 3 × 4 mixed design | N = 92 M(SD)age = 36.4 (13.3) 66.2% female | P: 60.2% students, 39.8% hospital employees 91.1% participants drinking at least weekly | Convenience sample, recruited through posters and ads in the organisations | Not reported |

| Al-Hamdani and Smith (2017) [76] | Canada | To examine whether increasing the size of HWL and plain packaging lowers ratings of alcohol products and the consumers who use them, increases ratings of bottle “boringness” and enhances warning recognition compared with branded packaging. | Online (survey) | Experiment: 3 × 2 × 3 mixed design | N = 440 initially/241 finally M(SD)age = 26 (7.1) 51.7% female | IC: Adults of legal age who consumed alcohol in the past 12 months P: 91% participants drinking at least weekly | Convenience sample, recruited online | Not reported |

| Annunziata et al. (2019) [70] | Italy and France | To analyse Generation Y consumers’ preferences for, interest in and attitudes towards different formats of health warnings on wine labels in two countries with different legal approaches: France and Italy. | Online (survey) | Discrete choice experiment | N = 500 (250 per country) M(SD)age = 23.3 (3.4)—FR; 25.2 (4.5)—IT 54% females—FR; 60% females—IT | IC: Generation Y (1978–2000) | Convenience sample, recruited online | 2018 |

| Blackwell et al. (2018) [71] | UK | To examine the influence of unit labels and health warnings on drinkers’ understanding, attitudes and behavioural intentions regarding drinking and examine optimal methods of delivering this information on labels. | Online (survey) | Between subjects experimental study | N = 1184 M(SD)age = 35 (12) 50% female | IC: Adult (18+) drinkers only | Recruitment through crowdsourcing platform/panel | Not reported |

| Clarke, Pechey et al. (2021a) [55] | UK | To obtain a preliminary assessment of the possible impact of (i) image-and-text, (ii) text only and (iii) image-only HWLs on selection of alcoholic versus non-alcoholic drinks. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study, 2 × 2 factorial design | N = 6024 (completed the study) M(SD)age = 49.5 (15.5)50% female | IC: Adults (18+) who consumed beer or wine regularly (i.e., at least once a week) | Recruited via market research agency | 2019 |

| Clarke, Blackwell et al. (2021b) [56] | UK | To estimate the impact of HWLs describing adverse health consequences of excessive alcohol consumption on selection of alcoholic drinks. | Naturalistic shopping laboratory | Between-subjects design | N = 399 M(SD)age = 39.9 (13.7)55% female | IC: Adults (18+) who purchased beer or wine weekly to drink at home | Recruited via market research agency | 2020 |

| Glock and Krolak-Schwerdt (2013) [72] | Luxembourg and Germany | Compared the effectiveness of warning labels that contradicted positive outcome expectancies with health-related warning labels. | Laboratory | Between-subjects experimental study, two factorial mixed design | N = 40 M(SD)age = 24.0 (3.2) 60% female | P: Undergraduates, native German speakers 95% drinkers | Recruited through university courses | Not reported |

| Gold et al. (2020) [63] | UK | To examine whether showing people a health warning alongside our label designs would have a further effect on our secondary outcomes, increasing the perceived risk of alcohol consumption, decreasing the motivation to drink and lowering the level of drinking which people believe to be health-damaging. | Online (survey) | Parallel randomisedcontrolled trial | N = 7516 total/500 for HWL M(SD)age = 44.2 (16.5)50.5% female | IC: English adults (18+) reporting drinking alcohol | Representative sample of the adult population of Englandin terms of age, gender and region, recruited through online panel platform | 2019 |

| Hall et al. (2019) [73] | US | To examine US adults’ reactions to health warnings with strong versus weak causal language. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 1360 M(SD)age = 37.4 (11.6) 47.3% female | IC: US residents, (18+) | Convenience sample, recruitment via online crowdsourcing platform | 2018 |

| Hall et al. (2020) [65] | US | To examine reactions to graphic versus text-only warnings for cigarettes, SSBs and alcohol. | Online (survey) | 2 × 2 × 3 Between-subjects experimental study | N= 1352 Mage = 37 47% female | IC: US residents, (18+) | Convenience sample, recruitment via online crowdsourcing platform | 2018 |

| Hobin, Schoueri-Mychasiw et al. (2020a) [51] | Canada | To examine the effects of strengthening alcohol labels on consumer attention and message processing, and a self-reported reduction in drinking due to the labels. | Real-world | Quasi experimental design | N = 2049 unique cohort participants M(SD)age = intervention 47.4 (14.6); comparison 41.2 (13.7) 50.7% female intervention, 45.1% female control | IC: Adult (19+), current drinkers (at least 1 drink in past 30 days), living in the intervention or comparison cities, bought alcohol at the liquor store and did not self-report being pregnant or breast-feeding | Systematic recruitment -standard intercept technique of approaching every person that passed a pre-identified landmark | 2017/2018 |

| Hobin, Weerasinghe et al. (2020b) [52] | Canada | To test the initial and continued effects of cancer warning labels on drinkers’ recall and knowledge that alcohol can cause cancer. | Real-world | Quasi experimental design | N = 2049 unique cohort participants M(SD)age = intervention 47.4 (14.6); comparison 41.2 (13.7) 50.7% female intervention, 45.1% female control | IC: Adult (19+) current drinkers (at least 1 drink in past 30 days), living in the intervention or comparison cities, bought alcohol at the liquor store, did not self-report being pregnant or breast-feeding | Systematic recruitment—standard intercept technique of approaching every person that passed a pre-identified landmark | 2017/2018 |

| Hobin, Shokar et al. (2020c) [54] | Canada | To investigate the impact of alcohol labels on (i) unprompted recall of label messages, (ii) depth of cognitive processing of label messages and (iii) self-reported impact on alcohol consumption. | Real-world | Quasi experimental design | N= 1647 unique cohort participants Age: Intervention: 6.8% 19–24, 34.3% 25–44, 58.8% 45 + Control: 12.3% 19–24, 45.5% 25–44, 42.2% 45 + 51.5% female intervention, 44.1% female control | IC: Adult (19+) current drinkers (at least 1 drink in past 30 days), living in the intervention or comparison cities, bought alcohol at the liquor store, did not self-report being pregnant or breast-feeding | Systematic recruitment—standard intercept technique of approaching every person that passed a pre-identified landmark | 2017/2018 |

| Jarvis and Pettigrew (2013) [74] | Australia | To assess the effects of warning statements on youth’s alcohol purchase decisions in the context of information relating to proprietary brands and alcohol content. | Online (survey) | Discrete choice experiment | N = 300 Age and gender not reported | IC: 18–25 year old current drinkers of pre-mixed alcoholic beverages, purchased a packaged pre-mixed alcoholic beverage in the past the 4 weeks | Through web panel provider, including equal proportional representation of two age categories | Not reported |

| Jongenelis, Pettigrew et al. (2018a) [58] | Australia | To examine the effectiveness of messages when delivered by single versus multiple sources. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 2087 M(SD)age= 36.05 (12.67) 50.1% female | IC: Adult drinkers consuming alcohol at least twice per month | Web panel provider | Not reported |

| Jongenelis, Pratt et al. (2018b) [59] | Australia | To examine whether exposing at-risk drinkers to warning statements relating to specific chronic diseases increases the extent to which alcohol is believed to be a risk factor for those diseases and influences consumption intentions. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 364 18–34 years 29% 35–65 years 71% 28% female | IC: Adults 18–65 years who reported drinking at levels associated with long-term risk of harm (more than 2 SD per day) | Web panel provider | Not reported |

| Krischler and Glock (2015) [68] | Luxembourg and Germany | To investigate the effectiveness of alcohol warning labels tailored toward young adults’ positive outcome expectancies. | Laboratory | Experiment: 3 × 2 mixed design | N = 122 M(SD)age = 23.5 (3.5) 68.9% female | P: 91.7% Undergraduates | Recruited on campus | 2014 |

| Ma (2021) [69] | US | To determine the impact of pictorial warning labels featuring narrative content on risk perceptions and behavioural intentions. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 169 M(SD)age = 43.2 (11.5) 37.9% female | IC: Alcohol consumers | Recruited through web panel provider | Not reported |

| Monk et al. (2017) [66] | UK | To investigate the amount of time spent looking at the different elements of alcohol-related health warnings. | Laboratory | Experiment: 2 × 2 × 2 mixed factorial design | N = 22 M(SD)age = 21.3 (1.7) 68.2% female | University students | Opportunity sampling | Not reported |

| Morgenstern et al. (2021) [67] | Germany | To investigate impact of alcohol warning labels on knowledge and negative emotions. | Online (survey) | Three factorial experiment | N = 9260 M(SD)age = 12.9 (1.8) 48.6% female | IC: Secondary school students (10–17) | Recruited through schools from randomly selected sub-regions | 2017–2018 |

| Pechey et al. (2020) [57] | UK | to describe the potential effectiveness and acceptability of image-and-text (also known as pictorial or graphic) HWLs applied to alcoholic drinks. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 5528 M(SD)age = 47.5 (15.8) 50.9% female | IC: 18+, self-reported consuming either beer or wine at least once a week | Purposeful sampling to include range of age, gender and social grades (recruited via market research agency) | 2018 |

| Pettigrew et al. (2016) [60] | Australia | To investigate the potential effectiveness of alcohol warning statements designed to increase awareness of the alcohol–cancer link. | Online (survey) | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 1680 < 31 years 49.5 31–45 years 25.2 46–65 years 25.3 49.9% female | IC: Adult (18–65) drinkers, consuming alcohol at least two days per month | Web panel provider | Not reported |

| Pham et al. (2018) * [50] | Australia | To investigate attention of current in market alcohol warning labels and examine whether attention can be enhanced through theoretically informed design. | Study 1: Online (survey) Study 2: Laboratory | Between-subjects experimental study | Study 1: N = 559 M(SD)age = 31.9 (7.8) Gender not reported Study 2: N = 87 M(SD)age = 26.6 (10.5)Gender not reported | Study 1: P: 72% employed, 6.6% full time students Study 2: P 49.4% full time students, 41.4% employed | Study 1: Snowball recruitment online Study 2: Face to face on campus | 2015 |

| Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] | UK | To examine whether enhancing self-affirmation among a population of drinkers, prior to viewing threatening alcohol pictorial health warning labels, would reduce defensive reactions and promote reactions related to behaviour change, and whether there is an interaction between self-affirmation and severity of warning. | Laboratory | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 128 M(SD)age = 22 (4) Gender not reported | IC: Adult (18+) regular alcohol consumers who have consumed over 14 units per week during the preceding week | Opportunity sampling, recruited via e-mail, posters and websites | Not reported |

| Stafford and Salmon (2017) [62] | UK | To test whether the speed of alcohol consumption is influenced by the type of alcohol health warning contained on the beverage. | Laboratory | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 45 M(SD)age = 18.9 (1.1) 100% female | IC: Female (18–25) regular alcohol consumers | Recruited using an online system and via social media | Not reported |

| Wigg and Stafford (2016) [61] | UK | To test the effectiveness of a range of alcohol health warnings, comparing no health warning, text only and pictorial warning. | Laboratory | Between-subjects experimental study | N = 60 M(SD)age = 19.4 (3.1) 71.7% female | IC: Alcohol consumers | Recruited using an online system, received credit points | Not reported |

| Zhao et al. (2020) [53] | Canada | To test if the labelling intervention was associated with reduced alcohol consumption. | Real-world | Quasi experimental design | Monthly retail sales data, no individual participants | Population 15+ in the research areas | / | 2017/2018 |

| N | % | Papers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude | 11 | 41% | Al-Hamdani & Smith (2015) [64]; Al-Hamdani & Smith (2017) [76]; Annunziata et al. (2019) [70]; Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt (2013) [72]; Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Jarvis & Pettigrew (2013) [74]; Jongenelis et al. (2018a) [58]; Krischler & Glock (2015) [68]; Pettigrew et al. (2016) [60]; Stafford & Salmon (2017) [62] |

| Intentions | 8 | 30% | Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt (2013) [72]; Jongenelis et al. (2018a) [58]; Jongenelis et al. (2018b) [59]; Krischler & Glock (2015) [68]; Ma (2021) [69]; Pettigrew et al. (2016) [60]; Wigg & Stafford (2016) [61] |

| Emotion | 7 | 26% | Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Clarke et al. (2021b) [56]; Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Ma (2021) [69]; Morgenstern et al. (2021) [67]; Pechey et al. (2020) [57]; Wigg & Stafford (2016) [61] |

| Acceptability/support | 7 | 26% | Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Clarke et al. (2021b) [56]; Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Hall et al. (2019) [73] Hobin et al. (2020b) [52]; Pechey et al. (2020) [57] |

| Behaviour | 6 | 22% | Clarke et al. (2021b) [56]; Hobin et al. (2020a) [51]; Hobin et al. (2020c) [54]; Morgenstern et al. (2021) [67]; Stafford & Salmon (2017) [62]; Zhao et al. (2020) [53] |

| Awareness/recognition | 5 | 19% | Al-Hamdani & Smith (2015) [64]; Al-Hamdani & Smith (2017) [76]; Hobin et al. (2020a) [51]; Hobin et al. (2020b) [52]; Hobin et al. (2020c) [54] |

| Risk perception | 5 | 19% | Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Gold et al. (2020) [63]; Ma (2021) [69]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75]; Wigg & Stafford (2016) [61] |

| Motivation | 4 | 15% | Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Gold et al. (2020) [63]; Pechey et al. (2020) [57]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] |

| Reactance | 4 | 15% | Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] |

| Knowledge | 3 | 11% | Hobin et al. (2020b) [52]; Jongenelis et al. (2018b) [59]; Morgenstern et al. (2021) [67] |

| Perceived effectiveness | 3 | 11% | Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Hall et al. (2019) [73]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] |

| Attention | 3 | 11% | Monk et al. (2017) [66]; Pham et al. (2018) [50]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] |

| Cognitive processing | 3 | 11% | Hall et al. (2020) [65]; Hobin et al. (2020a) [51]; Hobin et al. (2020c) [54] |

| Avoidance | 3 | 11% | Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Clarke et al. (2021a) [55]; Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] |

| Efficacy | 2 | 7% | Blackwell et al. (2018) [71]; Hall et al. (2020) [65] |

| Authors | Studied Groups/Variables (Independent Variables) | Outcome (Dependent Variable) | Category | Significant Results * (< Lower Than, > Higher Than) | Mechanism of Impact (if Tested) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hamdani & Smith (2015) [64] | Between subjects:

Within subjects:

| Product-based perception | Attitude | Plain packaging < Standard (all three alcohol types) Text and image < Standard (all three alcohol types) Text < Image (spirits only) | |

| Consumer-based perception | Attitude | Plain packaging < Standard (all three alcohol types) Text and image < Standard (wine and spirits only) No difference text and plain packaging | |||

| Warning recognition | Awareness/recognition | Higher odds of recognition of warning on plain packaged bottle of wine (but not beer and spirits) | |||

| Al-Hamdani & Smith (2017) [76] | Between subjects:

| Product-based perception | Attitude | Plain packaging < Branded, no difference in size Interaction between alcohol type and branding and warning size (Extra large < Medium (wine and spirits only) | |

| Consumer-based perception | Attitude | Plain packaging < Branded, no difference in size | |||

| Boringness of the bottle | Attitude | No difference in size or branding Interaction between alcohol type and branding | |||

| Warning recognition | Awareness/recognition | Higher odds of recognition of warning on plain packaged spirit bottle (but not beer and wine) | |||

| Annunziata et al. (2019) [70] | Attributes:

| Utility | Attitude | By attribute importance: No pictorial > Pictorial Back label > Front label No message > Neutral framed Message > Negative framed message | |

| Blackwell et al. (2018) [71] | Between subjects:

| Support for alcohol labelling | Acceptability/support | Support HWL < Support calorie information and strength information | |

| Motivation to drink less | Motivation | Cancer message > Mental health message Negative framing > Positive framing No difference in specificity | |||

| Reactance | Reactance | Specific message < General message Negative framing > Positive framing No difference in content | |||

| Avoidance | Avoidance | Cancer message > Mental health message Negative framing > Positive framing No difference in specificity | |||

| Believability | Attitude | Specific message > General message No difference in framing and content | |||

| Self-efficacy | Efficacy | No difference in any characteristic | |||

| Response efficacy | Efficacy | Specific message > General message No difference in framing and content | |||

| Clarke, Pechey et al. (2021a) [55] | Between subjects:

| Negative emotional arousal | Emotions | Any HWL > No HWL Image and text > Text only | (T) Tested model suggested negative emotional arousal possibly mediates the effect of HWL on alcohol selection |

| Acceptability of labels | Acceptability/support | Text > Image and text > Image only | |||

| Reactance | Reactance | Any HWL > No HWLImage and text > Text only | |||

| Avoidance | Avoidance | Any HWL > No HWL Image and text > Text only Image > Image and text | |||

| Perceived disease risk | Risk perception | Any HWL > No HWL No difference between HWLs | |||

| Proportion of participants selecting an alcoholic beverage to be consumed either immediately or later on that day | Intentions | Any HWL < No label Image or Image and text < Text alone | |||

| Clarke, Blackwell et al. (2021b) [56] | Between subjects:

| Negative emotional arousal | Emotions | Image and text > text | |

| Acceptability of labels | Acceptability/support | Text > Image and text | |||

| Proportion of total alcoholic drinks among all selected | Behaviour | No difference between the three groups | |||

| Glock & Krolak-Schwerdt (2013) [72] | Between subjects:

Within subjects:

| Implicit attitudes | Attitude | Interaction between warning and time: Health labels: before < after Positive expectancies: before > after | |

| Explicit attitudes | Attitude | No difference | |||

| Intention to drink | Intentions | Health-related > Positive-related | |||

| Gold et al. (2020) [63] | Between subjects:

| Perceived personal risk | Risk perception | No difference | |

| Motivation to drink less | Motivation | No difference | |||

| Perception of damaging drinking | Risk perception | No difference | |||

| Hall et al. (2019) [73] | Between subjects:

| Perceived message effectiveness | Perceived effectiveness | Causes > Others (overall, for alcohol less than for cigarettes) | |

| Perceived message ineffectiveness | Perceived effectiveness | May contribute to > Others (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Public support | Acceptability/support | No difference in support in alcohol group | |||

| Hall et al. (2020) [65] | Between subjects:

Within subjects:

| Perceived message effectiveness | Perceived effectiveness | Image and text > Text (overall, and for alcohol) | |

| Believability | Attitude | Text > Image and text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Reactance | Reactance | Image and text > Text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Fear | Emotions | Image and text > Text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Thinking about harms | Cognitive processing | Image and text > Text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Product appeal | Attitude | Text > Image and text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Policy support | Acceptability/support | Text > Image and text (overall, and for alcohol) | |||

| Self-efficacy | Efficacy | No difference in efficacy information presence | |||

| Hobin, Schoueri-Mychasiw et al. (2020a) [51] | Between subjects:

| Recognition of labels | Awareness/recognition | Enhanced label > regular label | |

| Cognitive processing | Cognitive processing | Enhanced label > Regular label | (T) Consumer attention to and processing of label messages partially mediated the relationship between the enhanced alcohol warning labels and self-reported drinking less → suggests that strengthening HWL will increase their effectiveness because they draw attention to and increase processing of the labels | ||

| Self-reported impact on drinking (reduction) | Behaviour | Enhanced labels > Regular label | |||

| Hobin, Weerasinghe et al. (2020b) [52] | Between subjects:

| Prompted and unprompted recall | Awareness/recognition | Enhanced label > Regular label (largest difference between groups at T2) | |

| Knowledge of alcohol as carcinogen | Knowledge | Enhanced label > Regular label (largest difference between groups at T3) | |||

| Support for health warning labels on alcohol containers | Acceptability/support | Intervention: Agree (Wave 1 = 57.4%; Wave 2 = 57.3%; Wave 3 = 61.3%) Comparison: Agree (Wave 1 = 53.7%; Wave 2 = 51.6%; Wave 3 = 53.7%) | (T) Knowledge about alcohol causing cancer associated with greater likelihood of supporting health warning labels in the study | ||

| Hobin, Shokar et al. (2020c) [54] | Between subjects:

| Unprompted recall | Awareness/recognition | Enhanced label > Regular label (cancer label) | |

| Cognitive processing | Cognitive processing | Enhanced label > Regular label | |||

| Self-reported impact on drinking (reduction) | Behaviour | Enhanced labels > Regular label | |||

| Jarvis & Pettigrew (2013) [74] | Attributes:

| Utility | Attitude | Brand > Alcohol content > Warning statement Two warning statements significant: one positive and one negative | |

| Jongenelis, Pettigrew et al. (2018a) [58] | Between subjects:

| Intentions to reduce alcohol consumption | Intentions | Multiple source > Single source | |

| Message believability | Attitude | Multiple source > Single source | |||

| Message convincingness | Attitude | Multiple source > Single source | |||

| Personal relevance of the message | Attitude | Multiple source > Single source | |||

| Jongenelis, Pratt et al. (2018b) [59] | Between subjects:

| Alcohol as risk factor beliefs | Knowledge | Present message > Absent message (for all messages except for liver damage) | |

| Intentions to reduce alcohol consumption | Intentions | Present message > Absent message (for cancer, diabetes and mental illness message, but not for liver damage and heart disease) | |||

| Krischler & Glock (2015) [68] | Between subjects:

Within subjects:

| Drinking intentions | Intentions | No difference | |

| Individual outcome expectancies | Attitude | No difference | |||

| General outcome expectancies | Attitude | No difference | |||

| Ma (2021) [69] | Between subjects:

| Worry about developing alcohol-related cancer | Emotions | Narrative labels > no labels | |

| Feelings of risk of developing alcohol-related cancer | Risk perception | Narrative labels > no labels | |||

| Comparative likelihood of developing alcohol-related cancer | Risk perception | No difference | |||

| Perceived severity of harm of developing alcohol-related cancer | Risk perception | Narrative labels > no labels | (T) Mediation analysis found that narrative PWLs (vs. control) indirectly influenced intentions through worry, but not through feelings of risk, comparative likelihood, or perceived severity. | ||

| Intentions to reduce alcohol use | Intentions | No difference | |||

| Monk et al. (2017) [66] | Between subjects:

| Dwell time | Attention | Image > Text (overall and in the positive expectancies increase group)No difference between graphic or neutral, and between increase and decrease in positive expectancies | |

| Morgenstern et al. (2021) [67] | Between subjects:

| Knowledge about alcohol-related risks | Knowledge | Any label >No label (for cancer and liver cirrhosis) | |

| Self-report of alcohol use | Behaviour | No difference | |||

| Negative emotions | Emotions | Text and image > Text only (only for some messages—driving, liver cirrhosis, pharmaceuticals, minors) | |||

| Pechey et al. (2020) [57] | Between subjects:

| Negative emotional arousal | Emotions | Bowel cancer > Others (> liver cancer > liver cirrhosis > heart disease > liver disease > 7 types of cancer > breast cancer) | |

| Desire to consume the labelled product | Motivation | Bowel cancer < Liver cirrhosis < Breast cancer < Liver cancer < Heart disease < Liver disease < 7 types of cancer | |||

| Acceptability of the label | Acceptability/support | Low overall acceptability, Bowel cancer < Others (Breast cancer < Liver disease < 7 types of cancer < Liver cancer < Liver disease < Liver cirrhosis) | |||

| Pettigrew et al. (2016) [60] | Between subjects:

Within subjects:

| Intention to reduce alcohol consumption | Intentions | Pre < Post No difference between messages | |

| Believability of message | Attitude | Bowel cancer > Other messages | |||

| Convincingness of the message | Attitude | Bowel cancer > Other messages | |||

| Personal relevance of the message | Attitude | Bowel cancer > Other messages | |||

| Pham et al. (2018) [50] | Between subjects:

| Attention | Attention | Enhanced colour and size > Other groups | |

| Number and length of visual fixations | Attention | No difference between groups | |||

| Sillero-Rejon et al. (2018) [75] | Between subjects:

Within-subject:

| Visual attention | Attention | No difference in severity or self-affirmation | |

| Avoidance | Avoidance | Highly severe > Moderately severe No difference in self-affirmation | |||

| Reactance | Reactance | Highly severe > Moderately severe No difference in self-affirmation | |||

| Perceived susceptibility to health risks | Risk perception | No difference in severity or self-affirmation | |||

| Perceived warning effectiveness | Perceived effectiveness | Highly severe > Moderately severe No difference in self-affirmation | |||

| Motivation to drink less | Motivation | Highly severe > Moderate severe No difference in self-affirmation | |||

| Stafford & Salmon (2017) [62] | Between subjects:

| Product design evaluation | Attitude | Image and text HWL < No HWL No difference between text only and no HWL | (H) The mechanism responsible for slower consumption is theorised to be due to higher levels of fear arousal in the two health warning conditions |

| The duration to consume the test beverage | Behaviour | No HWL < Text HWL No HWL < Image and text HWL No difference between text HWL and image and text HWL | |||

| Wigg & Stafford (2016) [61] | Between subjects:

| Fear arousal | Emotions | Image and text HWL > Text HWL Image and text HWL > No HWL No difference between text HWL and no HWL | |

| Risk perception | Risk perception | Image and text HWL > No HWL No difference between text HWL and no HWL No difference between image and text HWL and text HWL | |||

| Intention to quit/reduce alcohol consumption | Intentions | Image and text HWL > No HWL No difference between text HWL and no HWL No difference between image and text HWL and text HWL | |||

| Zhao et al. (2020) [53] | Between subjects:

| Alcohol sales | Behaviour | Enhanced labels < Regular labels |

| Future Labelling Research |

|

| Development of mandatory labels |

As currently implemented mandatory and voluntary labels are often suboptimal, existing research on new health warning labels points to the following characteristics:

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kokole, D.; Anderson, P.; Jané-Llopis, E. Nature and Potential Impact of Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093065

Kokole D, Anderson P, Jané-Llopis E. Nature and Potential Impact of Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Scoping Review. Nutrients. 2021; 13(9):3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093065

Chicago/Turabian StyleKokole, Daša, Peter Anderson, and Eva Jané-Llopis. 2021. "Nature and Potential Impact of Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Scoping Review" Nutrients 13, no. 9: 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093065

APA StyleKokole, D., Anderson, P., & Jané-Llopis, E. (2021). Nature and Potential Impact of Alcohol Health Warning Labels: A Scoping Review. Nutrients, 13(9), 3065. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13093065