Psychological Risk Factors for the Development of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors: A Polish and Vietnamese Comparison

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiology of Eating Disorders

1.2. Psychological Risk Factors for Eating Disorders with Cross-Cultural Ccomparisons

1.3. Research Objective, Variables, and Research Questions

- Low self-esteem—an indicator of self-esteem level;

- Personal alienation—describes level of reflectiveness and emotional emptiness;

- Interpersonal insecurity—allows to determine the intensity of difficulties in expressing personal thoughts and feelings when other people are present, and the tendency to isolate oneself;

- Interpersonal alienation—refers to the level of disappointment, alienation, and lack of trust in relationships;

- Emotional dysregulation—an indicator describing the level of intensity of mood instability, impulsiveness, recklessness, anger, and a tendency towards self-destruction;

- Interoceptive deficits—an indicator describing one’s level of confusion in the accurate recognition of emotional states and stimuli from one’s own body;

- Perfectionism— an index of the intensity of the need for the highest possible accomplishment and the tendency to possess the maximal achievable standards for personal achievement;

- Asceticism—an indicator that describes tendency to seek purity through striving for spiritual ideals such as self-denial, self-discipline, self-restraint, and self-control. This concept encompasses the control of needs and drives, as well as it assesses positive connotations associated with reaching purity by the means of restraint, guilt, and shame regarding pleasure;

- Maturity fears—an indicator describing the strength of a person’s longing for the return to the safety of childhood. It is also associated with the fear of psychosexual puberty.

- Is there a difference between Polish and Vietnamese women in terms of the psychological factor (dispositions and traits) intensity in the research model and components describing the body image of the surveyed women, and additionally the intensity of restrictive and bulimic behaviors used by the surveyed women?

- What psychological factors (explanatory variable) are important for the development of restrictive and bulimic eating behaviors in Polish and Vietnamese women?

- What is the role of the body image in relation to the generation of restrictive and bulimic eating behaviors in young Polish and Vietnamese women? Is it an intermediary variable in their formation? If so, which aspects describing body image in the research model mediate the formation of restrictive and/or bulimic behaviors?

- Which of the psychological factors verified in the research model have significant direct impacts, and which are not significant for the development of restrictive and bulimic behaviors towards eating for young Polish and Vietnamese women?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. The Eating Disorders Inventory—EDI-3

- Item 3. I wish that I could return to the security of childhood.

- Item 61. I eat or drink in secrecy.

2.3.2. The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire-Appearance Scales

2.3.3. Body Mass Index (BMI)

2.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Psychological Factors, Body Image, and Eating Behavior in Young Polish and Vietnamese Women (Differences between the Groups)

- The average BMI in research groups was similar, the Vietnamese women turned out to not differ significantly (mean (M) = 21.02) from the Polish women (M = 21.53) of the same age (p > 0.05). The BMI values were within the normal weight ranges for the age of life in both trials.

- With the analyzed psychological factors, only interpersonal alienation and striving for thinness did not differentiate between Polish and Vietnamese women. All other factors (dispositions and psychological features) turned out to be significantly different between Polish and Vietnamese women. Vietnamese women obtained significantly higher mean severity values in terms of bulimic behavior and significantly higher values in relation to Polish women for low self-esteem, sense of alienation, personal alienation, lack of self-confidence (interpersonal insecurity) and interpersonal alienation. The differences were significantly higher (the highest level of difference between respondents) in terms of the intensity of emotional dysregulation, interoceptive deficits, perfectionism, asceticism, and the fear of maturity.

- The comparative analysis of the mean values also showed significant differences between Polish and Vietnamese women in terms of the body image. Vietnamese women obtained a significantly lower level of perceived satisfaction with their overall appearance and lower satisfaction with individual body areas than Polish women. Vietnamese women were also significantly less oriented towards looking after their appearance than Polish women (appearance orientation). Vietnamese women also showed a significantly lower level of preoccupation towards being overweight and the fear of obesity (overweight preoccupation) than Polish women, and the frequency of focusing and monitoring their own weight, using various diets and dieting overall, and lower levels of self-classified weight were all lower than Polish women; however, although the indicated differences were statistically significant, they were lower than the differences in the case of other psychological factors included in the study profile. Polish women were more focused on the fear of gaining weight and body weight but also show a higher level of satisfaction with their own body and care for appearance than Vietnamese women.

3.2. Psychological Predictors of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behavior

3.2.1. Analysis of Psychological Predictors of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors in a Group of Polish Women

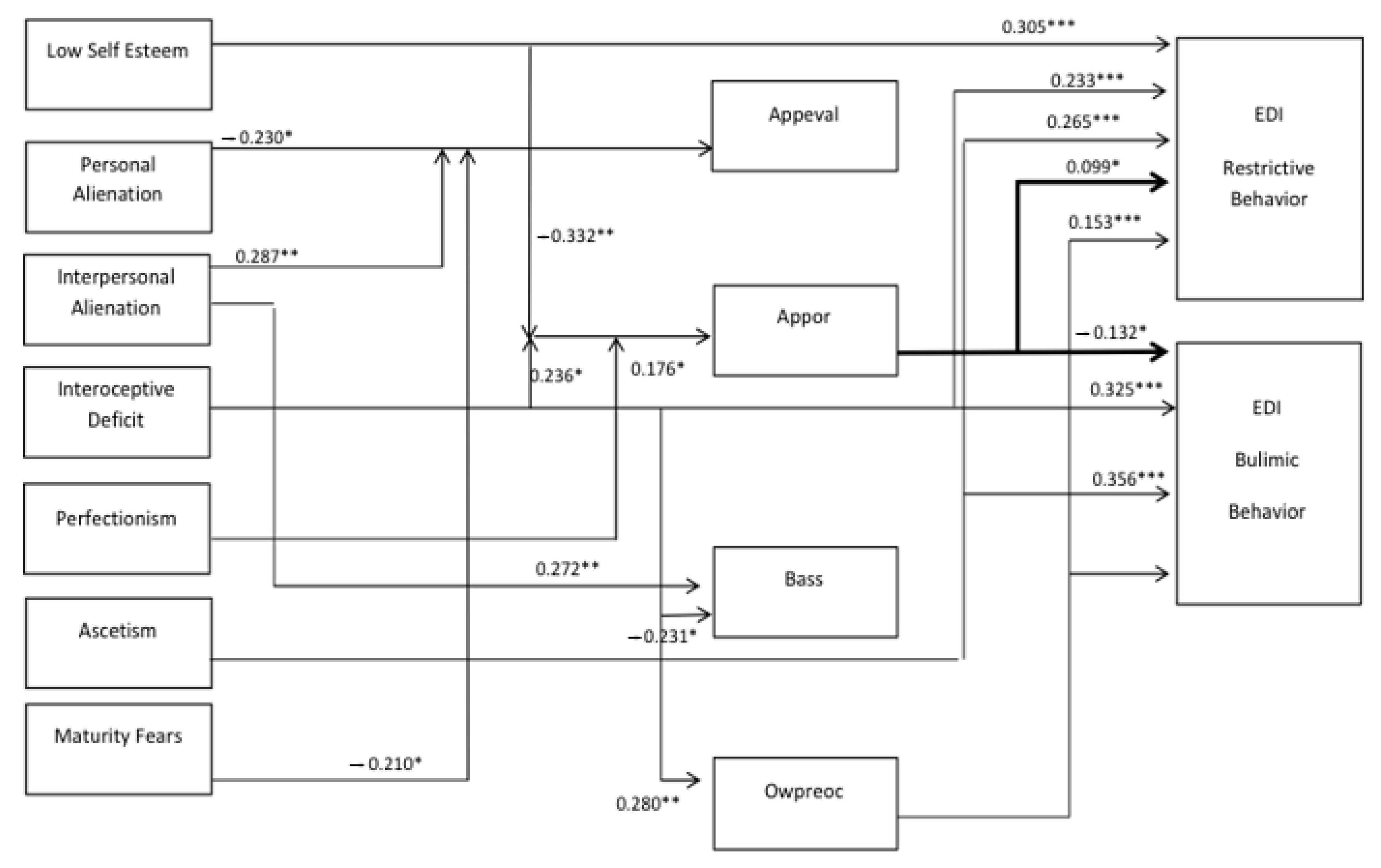

- Low self-esteem (0.305; p = 0.001): The lower the self-esteem, the greater the strive for thinness and the prevalence of restrictive behavior in Polish women.

- Asceticism (0.265; p = 0.001): The greater the intensity of asceticism, the greater the strive for thinness and restrictive behavior in Polish women.

- Interoceptive deficits (0.233; p = 0.001): The higher the interoceptive deficits, the greater the intensity of striving for thinness and the prevalence of restrictive behavior in Polish women.

- Overweight preoccupation—preoccupation with being overweight and assessment of the level of fear of obesity (0.153; p = 0.001). The greater the fear of obesity and preoccupation with being overweight, the greater its influence on restrictive behavior and striving for thinness in Polish women.

- Appearance orientation (0.099; p = 0.037): The greater the attention to appearance, the greater the strive for thinness and restrictive behavior in Polish women.

- Asceticism (0.356; p = 0.001): The greater the intensity of asceticism, the greater the intensity of bulimic behavior in Polish women.

- Interoceptive deficits (0.325; p = 0.001): The greater the interoceptive deficits, the greater the prevalence of bulimic behavior.

- Interpersonal alienation showed a significant impact on both appearance evaluation (0.287; p = 0.002) and body area satisfaction (0.272; p = 0.004). The greater the level of interpersonal alienation for Polish women, the greater the impact on general appearance satisfaction and BAS.

- Personal alienation showed a significant negative impact on appearance evaluation, where the greater the personal alienation, the smaller the impact on the assessment of satisfaction with appearance (−0.230, p = 0.028). Similarly, maturity fears showed a significant negative direct impact on appearance evaluation (−0.210; p = 0.031), where the greater the level of fear of adulthood, the lower the level of body appearance satisfaction for Polish women.

- Interoceptive deficits showed a significant direct impact on body area satisfaction (−0.231; p = 0.026), where the greater the interoceptive deficits were in Polish women, the lower the level of satisfaction with the appearance of individual body areas, and the same psychological variable showed a direct impact on overweight preoccupation (0.280, p = 0.007), where the greater the interoceptive deficits, the greater the impact of the level of anxiety about gaining weight and the frequency of monitoring one’s own weight (weight vigilance).

- Low self-esteem (−0.332; p = 0.007): When self-esteem is lower and the sense of worthlessness is higher, the level of care for appearance is lower in Polish women.

- Interoceptive deficits (0.236; p = 0.021): The higher the interoceptive deficits, the higher the impact on the higher level of care for appearance in Polish women.

- Perfectionism (0.176; p = 0.016): With higher perfectionism, the greater its importance becomes for caring for appearance and the development of striving for thinness and restrictive behavior, but with a lower intensity of bulimic behavior.

3.2.2. Analysis of Psychological Predictors of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behavior in the Group of Vietnamese Women

- Asceticism (0.123; p = 003): The higher the level of asceticism, the greater its influence on undertaking restrictive behavior and striving for thinness.

- Interoceptive deficits (0.101; p = 0.018): The higher the deficits in interoceptive awareness, the greater their direct impacts on developing restrictive behaviors and striving for thinness.

- Personal alienation (−0.096; p = 0.032): The greater the level of personal alienation, the smaller its direct impact is on the pursuit of thinness and restrictive behavior for Vietnamese women.

- Overweight preoccupation, i.e., the assessment of the level of fear of obesity (0.808; p = 0.001), where the greater the fear of obesity and preoccupation with being overweight, the greater its impact on restrictive behavior and thinness in Vietnamese women. Overweight preoccupation represented the strongest impact in the entire path model.

- Body area satisfaction, i.e., the assessment of satisfaction with individual body areas (−0.384; p = 0.001), where the better the assessment of satisfaction with individual areas of the body, the smaller their impact on restrictive behavior and striving for thinness in Vietnamese women.

- Appearance orientation (−0.062; p = 0.031) and appearance evaluation (0.068; p = 0.047), where the greater the focus on looking after the appearance, the lower the restrictive behavior, but also the greater the satisfaction with the assessment of the appearance and stronger restrictive behavior development and focus on the pursuit of body thinness.

- Interoceptive deficits (0.328, p = 0.001): The greater the interoceptive deficits, the greater the tendency to develop bulimic behavior.

- Ascetism (0.223; p = 0.001): The greater the ascetism, the greater the tendency to develop bulimic behavior.

- Overweight preoccupation (0.117; p = 0.009): The greater the preoccupation with being overweight and the fear of obesity, the greater the intensity of bulimic behavior.

- Appearance evaluation (0.014; p = 0.033): The higher the satisfaction with the appearance of the body, the greater the intensity of bulimic behavior.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Characteristics of Psychological Factors as Well as Restrictive and Bulimic Behaviors in Polish and Vietnamese Women

4.2. Psychological Predictors of Behavior towards Eating with a Polish and Vietnamese Comparison

4.2.1. Interoceptive Deficits, Asceticism, and Low Self-Esteem as Predictors of Restrictive and Bulimic Behaviors

4.2.2. Body Image as an Intermediary Variable between Psychological Factors and Restrictive and Bulimic Behaviors.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galmiche, M.; Déchelotte, P.; Lambert, G.; Tavolacci, M.P. Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1402–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, H.W. Review of the worldwide epidemiology of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilbert, A.; De Zwaan, M.; Braehler, E. How Frequent Are Eating Disturbances in the Population? Norms of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotwas, A.; Karakiewicz-Krawczyk, K.; Zabielska, P.; Jurczak, A.; Bażydło, M.; Karakiewicz, B. The incidence of eating disorders among upper secondary school female students. Psychiatr. Polska 2020, 54, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilecki, M.W.; Sałapa, K.; Józefik, B. Socio-cultural context of eating disorders in Poland. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Prevalence and Correlates of DSM-5–Defined Eating Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 84, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodside, D.B.; Garfinkel, P.E.; Lin, E.; Goering, P.; Kaplan, A.S.; Goldbloom, D.S.; Kennedy, S.H. Comparisons of Men With Full or Partial Eating Disorders, Men Without Eating Disorders, and Women With Eating Disorders in the Community. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolar, D.R.; Rodriguez, D.L.M.; Chams, M.M.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Latin America. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, W.; Fatima, R.; Anwar, N.S. Disordered Eating Attitude and Body Dissatisfaction among Adolescents of Arab Countries: A Review. Asian J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 12, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Mannai, M.; Tayyem, R.; Al-Lalla, O.; Ali, E.Y.; Kalam, F.; Benhamed, M.M.; Saghir, S.; Halahleh, I.; Djoudi, Z.; et al. Risk of disordered eating attitudes among adolescents in seven Arab countries by gender and obesity: A cross-cultural study. Appetite 2013, 60, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoeken, D.; Burns, J.K.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Africa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, K.M.; Dunne, P.E. The rise of eating disorders in Asia: A review. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.J.; Lee, S.; Becker, A.E. Updates in the epidemiology of eating disorders in Asia and the Pacific. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, J.; Miao, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Lai, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hsu, L.K.G. A two-stage epidemiologic study on prevalence of eating disorders in female university students in Wuhan, China. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 49, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, G. Eating disorders in the Far East. Eat Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2000, 5, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, N.; Tam, D.M.; Viet, N.K.; Scheib, P.; Wirsching, M.; Zeeck, A. Disordered eating behaviors in university students in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.; Soysa, C.K. Eating Pathology in International Vietnamese and White American Undergraduate Women in the United States. Psi Chi J. Psychol. Res. 2019, 24, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, V.L. Eating disorders: From the perspective as a form of psychosis. Sci. J. 2017, 14, 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, L.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Molina, A.J.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.; Martín, V. Incidence of Anorexia Nervosa in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Svansdottir, E.; Sigurdsson, H.; Arnarsson, A.; Ommundsen, Y.; Arngrimsson, S.; Sveinsson, T.; Johannsson, E. Different factors associate with body image in adolescence than in emerging adulthood: A gender comparison in a follow-up study. Health Psychol. Rep. 2018, 6, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, M.; Lipowski, M. Narcissism as a Moderator of Satisfaction with Body Image in Young Women with Extreme Underweight and Obesity. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Rosselli, F.; Perrin, N.; DeBar, L.; Wilson, G.T.; Ma, A.M.; Kraemer, H.C. Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2008, 42, 471–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, S.B.; Nagata, J.M.; Griffiths, S.; Calzo, J.P.; Brown, T.A.; Mitchison, D.; Blashill, A.J.; Mond, J.M. The enigma of male eating disorders: A critical review and synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowski, M.; Lipowska, M. Poziom narcyzmu jako moderator relacji pomiędzy obiektywnymi wymiarami ciała a stosunkiem do własnej cielesności młodych mężczyzn [The role of narcissism in the relationship between objective body measurements and body self-esteem of young men]. Pol. Forum Psychol. 2015, 20, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Salomon, J.; A Haagsma, J.; Davis, A.; de Noordhout, C.M.; Polinder, S.; Havelaar, A.H.; Cassini, A.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Kretzschmar, M.; Speybroeck, N.; et al. Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, e712–e723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Whiteford, H.A.; Pike, K.M. The global burden of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smink, F.R.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2013, 26, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stämpfli, A.E.; Stöckli, S.; Brunner, T.A.; Messner, C. A Dieting Facilitator on the Fridge Door: Can Dieters Deliberately Apply Environmental Dieting Cues to Lose Weight? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lizińczyk, S.; Lipiarz, A. Psychological Predictors of Unhealthy Eating Attitudes in Young Adults. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, M.M. Cues to overeat: Psychological factors influencing overconsumption. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2007, 66, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Truong Thi Khanh, H.; Lizińczyk, S.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lipowska, M.; Gulbicka, A. Body Dissatisfaction, Restrictive, and Bulimic Behaviours Among Young Women: A Polish–Japanese Comparison. Nutrients 2020, 12, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, M.; Khanh, H.T.T.; Lipowski, M.; Różycka-Tran, J.; Bidzan, M.; Ha, T.T.; Thu, T.H. The Body as an Object of Stigmatization in Cultures of Guilt and Shame: A Polish–Vietnamese Comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, M.; Horikawa, R.; Mabe, H.; Yokoyama, S.; Sugiyama, E.; Yonekawa, T.; Nakazato, M.; Okamoto, Y.; Ohara, C.; Ogawa, Y. Epidemiology of anorexia nervosa in Japanese adolescents. Biopsychosoc. Med. 2015, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakai, Y.; Nin, K.; Noma, S.; Teramukai, S.; Fujikawa, K.; Wonderlich, S.A. Changing profile of eating disorders between 1963 and 2004 in a Japanese sample. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 51, 953–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Nguyen, P.H.; Tran, L.M.; Huynh, P.N. Nutrition transition in Vietnam: Changing food supply, food prices, household expenditure, diet and nutrition outcomes. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toczyski, P.; Krejtz, K.; Ciemniewski, W. The Challenges of Semi-Peripheral Information Society: The Case of Poland. Stud. Glob. Ethics Glob. Educ. 2015, 3, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W. Women, Westernization and the Origins of Modern Vietnamese Theatre. J. Southeast Asian Stud. 2006, 37, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, U. Vietnam?s integration into the global economy. Achievements and challenges. Asia Eur. J. 2004, 2, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, H.; Schweisshelm, E.; Vu, T.-M. The Integration of Vietnam in the Global Economy and Its Effects for Vietnamese Economic Development; International Labour Organization: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, M.H.; Dhavan, P.; Van Dusen, D.; Arora, M.; Reddy, K.S.; Perry, C.L. Westernization and tobacco use among young people in Delhi, India. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 71, 891–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swami, V.; Frederick, D.A.; Aavik, T.; Alcalay, L.; Allik, J.; Anderson, D.; Andrianto, S.; Arora, A.; Brännström, Å.; Cunningham, J.; et al. The Attractive Female Body Weight and Female Body Dissatisfaction in 26 Countries Across 10 World Regions: Results of the International Body Project I. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 36, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompper, D.; Koenig, J. Cross-Cultural-Generational Perceptions of Ideal Body Image: Hispanic Women and Magazine Standards. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2004, 81, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, E.G.; Awad, G.H. Cultural Influences on Body Image and Body Esteem. In The Cambridge Handbook of the International Psychology of Women; Halpern, D.F., Cheung, F.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, A.; Le, D.-S.N.T.; Tran, M.-H.T.; Pham, H.T.N.; Kaneda, M.; Murai, E.; Kamiyama, H.; Oota, Y.; Yamamoto, S. Study on Factors of Body Image in Japanese and Vietnamese Adolescents. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2008, 54, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Czepczor-Bernat, K.; Kościcka, K.; Gebauer, R.; Brytek-Matera, A. Ideal body stereotype internalization and sociocultural attitudes towards appearance: A preliminary cross-national comparison between Czech, Polish and American women. Arch. Psychiatry Psychother. 2017, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Bissell, K. The Globalization of Beauty: How is Ideal Beauty Influenced by Globally Published Fashion and Beauty Magazines? J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 2014, 43, 194–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podczarska-Głowacka, M.; Karasiewicz, K. Health behaviours as mediators of relationships between the actual image and real and ideal images of one’s own body. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 10, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, P.H.B.; Alvarenga, M.D.S.; Ferreira, M.E.C. An etiological model of disordered eating behaviors among Brazilian women. Appetite 2017, 116, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.; Tiggemann, M. A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image 2016, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Melioli, T. The Relationship Between Body Image Concerns, Eating Disorders and Internet Use, Part I: A Review of Empirical Support. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2016, 1, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F. The Relationship Between Body Image Concerns, Eating Disorders and Internet Use, Part II: An Integrated Theoretical Model. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2015, 1, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Z.; Tiggemann, M. Celebrity influence on body image and eating disorders: A review. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 10, 1359105320988312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manku, R.; Egan, H.; Keyte, R.; Hussain, M.; Mantzios, M. Dieting, mindfulness and mindful eating:exploring whether or not diets reinforce mindfulness and mindful eating practices. Health Psychol. Rep. 2020, 8, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.C.; Rąba, M.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K. Resilience, self-esteem, and body attitude in women from early to late adulthood. Health Psychol. Rep. 2018, 6, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoi, S.L.; Vasquez, K.; Sparapani, E.; Frost, K.; Martin, J.; Aebly, M. Exploring Body Comparison Tendencies. Psychol. Women Q. 2011, 36, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K. Sociocultural Appearance Standards and Risk Factors for Eating Disorders in Adolescents and Women of Various Ages. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agüera, Z.; Paslakis, G.; Munguía, L.; Sánchez, I.; Granero, R.; Sánchez-González, J.; Steward, T.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Gender-Related Patterns of Emotion Regulation among Patients with Eating Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, B. A psychological typology of females diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder. Health Psychol. Rep. 2015, 4, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, D.M. EDI 3: Eating Disorder Inventory-3: Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cash, T.F.; Grasso, K. The norms and stability of new measures of the multidimensional body image construct. Body Image 2005, 2, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F. Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). In Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders; Wade, T., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 978–981. [Google Scholar]

- Brytek-Matera, A.; Rogoza, R. Validation of the Polish version of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire among women. Eat Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2015, 20, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B. Postawy i Zachowania Wobec Własnego Ciała w Zaburzeniach Odżywiania [Attitudes and Behaviors Toward One’s Body in Eating Disorders]; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chisuwa, N.; O’Dea, J.A. Body image and eating disorders amongst Japanese adolescents. A review of the literature. Appetite 2010, 54, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Nin, K.; Noma, S. Eating disorder symptoms among Japanese female students in 1982, 1992 and 2002. Psychiatry Res. 2014, 219, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prefit, A.-B.; Cândea, D.M.; Szentagotai-Tătar, A. Emotion regulation across eating pathology: A meta-analysis. Appetite 2019, 143, 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Ballesio, A.; Lombardo, C. The relationship between perfectionism and eating-related symptoms in adolescents: A systematic review. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2021, 29, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, N.; Valois, D.D.; Bedford, S.; Norris, M.L.; Hammond, N.G.; Spettigue, W. Asceticism, perfectionism and overcontrol in youth with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord. Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2021, 26, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, P.M.; Taylor, L.; Laws, K.R. Self-reported interoceptive deficits in eating disorders: A meta-analysis of studies using the eating disorder inventory. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 110, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Forrest, L.; Velkoff, E. Out of touch: Interoceptive deficits are elevated in suicide attempters with eating disorders. Eat. Disord. 2018, 26, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.; Dourish, C.; Rotshtein, P.; Spetter, M.; Higgs, S. Interoception and disordered eating: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 166–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żechowski, C. Polska wersja Kwestionariusza Zaburzeń Odżywiania (EDI)–adaptacja i normalizacja [Polish version of Eating Disorder Inventory–Adaptation and normalization]. Psychiatr. Polska 2008, 42, 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla, E.F.; Birgegard, A. The enemy within: The association between self-image and eating disorder symptoms in healthy, non help-seeking and clinical young women. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lizińczyk, S.; Lipowska, M. Socio-Cultural Standards Promoted by the Mass Media as Predictors of Restrictive and Bulimic Behavior. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.N.; Salameh, R.A.; Yhya, H.H.; Sweileh, W.M. Disordered eating attitudes in female students of An-Najah National University: A cross-sectional study. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuis-De-Andrade, S.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Costa, D.B.; Da Silva, F.A.; Irigaray, T.Q.; Lara, D.R. The Association Between Eating-Compensatory Behaviors and Affective Temperament in a Brazilian Population. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borda Más, M.; Navarro, M.L.; Jiménez, A.; Pérez, I.T.; Sánchez, C.R.; Gregorio, M. Personality traits and eating disorders: Mediating effects of self-esteem and perfectionism. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2011, 11, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Mantilla, E.F.; Norring, C.; Birgegård, A. Self-image and 12-month outcome in females with eating disorders: Extending previous findings. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, F.; Rojo, S.F.; Banzo, C.; Quintero, J. The impact of self-esteem on eating disorders. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallorquí-Bagué, N.; Vintró-Alcaraz, C.; Sánchez, I.; Riesco, N.; Agüera, Z.; Granero, R.; Jiménez-Múrcia, S.; Menchón, J.M.; Treasure, J.; Fernández-Aranda, F. Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Feature Among Eating Disorders: Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Approach. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.A.; Haynos, A.F. A theoretical review of interpersonal emotion regulation in eating disorders: Enhancing knowledge by bridging interpersonal and affective dysfunction. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P. Loneliness and Eating Disorders. J. Psychol. 2012, 146, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hempel, R.; Vanderbleek, E.; Lynch, T.R. Radically open DBT: Targeting emotional loneliness in Anorexia Nervosa. Eat. Disord. 2018, 26, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, E.T.; Bornstein, M.H. Global Self-Esteem, Appearance Satisfaction, and Self-Reported Dieting in Early Adolescence. J. Early Adolesc. 2009, 30, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dea, J.A. Body image and self-esteem. In Encyclopedia of Body Image and Human Appearance; Cash, T.F., Ed.; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2012; pp. 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Izydorczyk, B.; Gut, A.; Dobrowolska, M. Samoocena i wpływ socjokulturowy na wizerunek ciała a gotowość do zachowań anorektycznych [Self-Esteem and Sociocultural Influence on Body Image and Readiness for Anorectic Behavior]. Czasopismo Psychologiczne 2018, 24, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Variable | Polish Women | Vietnamese Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me (25Q-75Q) | Me (25Q-75Q) | U | Z | p | |

| Eating Disorders Questionnaire (EDI-3) Behavior towards eating | |||||

| Driver for thinnes | 10.00(5.00–17.00) | 10.00 (5.00–17.00) | 79,513.0 | 0.34 | 0.730 |

| Bulimia | 3.00 (1.00–7.00) | 6.00 (3.00–10.00) | 56,919.5 | −7.13 | 0.001 |

| Body Dissatisfaction | 18.00 (14.00–21.00) | 22.00 (18.00–26.00) | 51,355.0 | −8.80 | 0.001 |

| Psychological factors | |||||

| Low Self-Esteem | 12.00 (9.00–15.00) | 13.00 (10.00–16.00) | 67,916.5 | −3.83 | 0.001 |

| Personal Alienation | 12.00 (8.00–15.00) | 14.00 (12.00–17.00) | 56,097.0 | −7.38 | 0.001 |

| Interpersonal Insecurity | 16.00 (11.00–20.00) | 18.00 (15.00–20.00) | 64,667.5 | −4.81 | 0.001 |

| Interpersonal Alienation | 12.50 (8.00–16.00) | 12.00 (11.00–15.00) | 76,013.0 | −1.40 | 0.162 |

| Interoceptive Deficits | 11.00 (6.00–17.00) | 14.00 (10.00–19.00) | 60,302.0 | −6.12 | 0.001 |

| EmotionalDysregulation | 8.00 (4.00–12.00) | 13.00 (9.00–17.00) | 48,208.0 | −9.75 | 0.001 |

| Perfectionism | 8.00 (4.00–12.00) | 11.00 (8.00–14.00) | 58,282.0 | −6.72 | 0.001 |

| Asceticism | 6.00 (4.00–10.00) | 8.00 (5.00–11.00) | 61,434.0 | −5.78 | 0.001 |

| Maturity Fears | 13.00 (9.00–16.00) | 19.00 (16.00–23.00) | 29,504.5 | −15.37 | 0.001 |

| Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ-AS) | |||||

| Apperance Evaluation | 3.14 (2.71–3.71) | 3.00 (2.57–3.43) | 47,362.0 | 4.12 | 0.001 |

| Apperance Orientation | 3.50 (3.17–3.83) | 3.25 (3.00–3.42) | 37,703.5 | 7.73 | 0.001 |

| Body Areas Satisfaction | 3.44 (2.89–3.78) | 2.78 (2.22–3.33) | 33,193.5 | 9.41 | 0.001 |

| Overweight Preoccupation | 2.50 (2.00–3.00) | 2.00 (1.50–3.25) | 49,239.5 | 3.41 | 0.001 |

| Self-Clasiffied Weigh | 3.00 (3.00–3.50) | 3.00 (2.00–3.50) | 48,466.5 | 3.70 | 0.001 |

| Explained Variables Psychological Factors | Predictors Group of Vietnamese Women | Predictors Group of Polish Women |

|---|---|---|

| Apperance evaluation | Low Self Esteem β = −0.483 *** | Personal Alienation β = −0.230 * |

| Apperance Orientation | Ascetism β = 0.154 * | Low Self Esteem β = −0.332 ** Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.236 * Perfectionism β = 0.176 ** |

| Βody Areas Satisfaction | Low Self Esteem β = −0.147 * | Interpersonal Alienation β = 0.272 ** Interoceptive Deficit β = −0.231 * |

| Overweight Preoccupation | Ascetism β = 0.173 * | Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.280 ** |

| Restrictive Behaviours | Apperance Evaluation β = 0.068 *Body Areas Satisfaction β = −0.384 *** Apperance Orientation β = −0.062 * Personal Alienation β = −0.096 * Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.101 * Ascetism β = 0.123 ** Overweight Preoccupation B = 0.808 *** | Low Self Esteem β = 0.305 *** Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.233 *** Ascetism β = 0.265 *** Apperance Orientation β = 0.099 *Overweight Preoccupation β = 0.153 *** |

| Bulimic Behaviours | Apperance Evaluation β = 0.104 * Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.328 *** Ascetism β = 0.223 *** Overweight Preoccupation β = 0.117 ** | Appor β = −0.132 * Interoceptive Deficit β = 0.325 *** Ascetism β = 0.356 ** Overweight Preoccupation β = −0.132 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izydorczyk, B.; Truong Thi Khanh, H.; Lipowska, M.; Sitnik-Warchulska, K.; Lizińczyk, S. Psychological Risk Factors for the Development of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors: A Polish and Vietnamese Comparison. Nutrients 2021, 13, 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030910

Izydorczyk B, Truong Thi Khanh H, Lipowska M, Sitnik-Warchulska K, Lizińczyk S. Psychological Risk Factors for the Development of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors: A Polish and Vietnamese Comparison. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):910. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030910

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzydorczyk, Bernadetta, Ha Truong Thi Khanh, Małgorzata Lipowska, Katarzyna Sitnik-Warchulska, and Sebastian Lizińczyk. 2021. "Psychological Risk Factors for the Development of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors: A Polish and Vietnamese Comparison" Nutrients 13, no. 3: 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030910

APA StyleIzydorczyk, B., Truong Thi Khanh, H., Lipowska, M., Sitnik-Warchulska, K., & Lizińczyk, S. (2021). Psychological Risk Factors for the Development of Restrictive and Bulimic Eating Behaviors: A Polish and Vietnamese Comparison. Nutrients, 13(3), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030910