Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

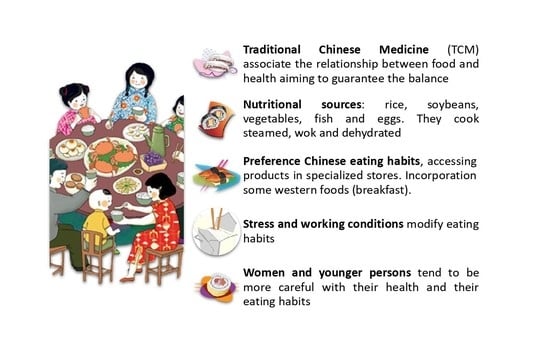

3.1. Differences between Chinese Food and Western Food

3.2. Products and Dishes Consumed by Chinese Immigrants

3.3. Modification of Food Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance to Clinical Practice

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Available online: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment. Available online: https://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/contents/en/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Van Praag, H.; Fleshner, M.; Schwartz, M.W.; Mattson, M.P. Exercise, Energy Intake, Glucose Homeostasis, and the Brain. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 15139–15149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Recomendaciones Mundiales Sobre Actividad Física Para la Salud. Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/es/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Wang, Y.; Min, J.; Harris, K.; Khuri, J.; Anderson, L.M. A Systematic Examination of Food Intake and Adaptation to the Food Environment by Refugees Settled in the United States. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kwasi, H.A.; Nicolaou, M.; Powell, K.; Terragni, L.; Maes, L.; Stronks, K.; Lien, N.; Holdsworth, M. Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe: A DEDIPAC study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-López, J.R.; Rodríguez-Gázquez, M.D.L.; Ángeles Lomas-Campos, M.D.L.M. Physical Activity in Latin American Immigrant Adults Living in Seville, Spain. Nurs. Res. 2015, 64, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornby-Turner, Y.C.; Hampshire, K.R.; Pollard, T.M. A comparison of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in 9–11 year old British Pakistani and White British girls: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drieling, R.L.; Rosas, L.G.; Ma, J.; Stafford, R.S. Community Resource Utilization, Psychosocial Health, and Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Diet and Physical Activity among Low-Income Obese Latino Immigrants. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, A.; Boulos, R.; Sliwa, S.; Must, A.; Gute, D.M.; Metayer, N.; Hyatt, R.R.; Chui, K.; Pirie, A.; Luongo, C.K.; et al. Baseline Socio-demographic characteristics and self-reported diet and physical activity shifts among recent immigrants participating in the randomized controlled lifestyle intervention: "Live Well". J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2013, 16, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, M.; Wright, D.J.; Fang, C.Y. Acculturation and Dietary Change Among Chinese Immigrant Women in the United States. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Rábago, Y.; La Parra, D.; Martín, U.; Malmusi, D.; La Parra-Casado, D. Participación y representatividad de la población inmigrante en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud de España 2011–2012. Gac. Sanit. 2014, 28, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andalusian Permanent Observatory of Migration (OPAM). Biennieal Report “Andalucía e Inmigración”. 2017. Available online: http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/justiciaeinterior/opam/en/informe_anual (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Llop-Gironés, A.; Aller, M.-B.; Lorenzo, I.V.; Garcia-Subirats, I.; Navarrete, M.L.V. Acceso a los servicios de salud de la población inmigrante en España. Rev. Española Salud Pública 2014, 88, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tormo, M.J.; Salmerón, D.; Colorado-Yohar, S.; Ballesta, M.; Dios, S.; Martínez-Fernández, C.; Pérez-Flores, D.; García-Pérez, V.; Palomar, J.A.; Torres, A.M.; et al. Resultados de dos encuestas dirigidas a inmigrantes y nativos del sureste español: Salud, uso de servicios y necesidad de asistencia médica. Salud Pública México 2015, 57, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koo, L.C. The use of food to treat and prevent disease in chinese culture. Soc. Sci. Med. 1984, 18, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Xu, Y.; Xiang, J. Prevalence, Trends and Associated Risk Factors of Overweight/Obesity among Rural-to-Urban Migrant Children in China. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 48, 1927–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-K.; Yin, X.-J.; Xiong, J.-P.; Liu, J.-J.; Watanabe, T.; Tanaka, T. Comparison of the status of overweight/obesity among the youth of local Shanghai, young rural-to-urban migrants and immigrant origin areas. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 2804–2814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roper, J.M.; Shapira, J. Ethnography in Nursing Research; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Szende Oaks, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Draper, J. Ethnography: Principles, practice and potential. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Statistics Institute. Available online: https://www.ine.es/en/prodyser/pubweb/anuarios_mnu_en.htm (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Ministry of Health Social Services and Equality (MHSSE). National Health Survey. 2017. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/categoria.htm?c=Estadistica_P&cid=1254734710984 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic Analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 978-981-10-2779-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zongzi. Available online: https://unsplash.com/s/photos/zongzi (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Chop Suey, Los Secretos de Esta Gran Receta Oriental. Available online: https://cocinateelmundo.com/cocina-asiatica/chop-suey/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Tangyuan. Available online: https://unsplash.com/s/photos/tangyuan (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Qingmingguo, Comida de primavera. Available online: http://spanish.xinhuanet.com/photo/2016-03/31/c_135239178.htm (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Moon Cake. Available online: https://unsplash.com/s/photos/moon-cake (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Zhao, Z.; Li, M.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Zhan, Z.; Dong, W.; Shen, Z.; Xu, M.; Lu, J.; et al. Dietary preferences and diabetic risk in China: A large-scale nationwide Internet data-based study. J. Diabetes 2020, 12, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Qi, L.; Yu, C.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Z.; Sun, D.; Du, J.; Ge, P.; et al. Consumption of spicy foods and total and cause specific mortality: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2015, 351, h3942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Where Is the Spiciest Place in China? 2016. Available online: http://www.china.org.cn/china/2016-06/10/content_38628877.htm (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Leung, G.; Stanner, S. Diets of minority ethnic groups in the UK: Influence on chronic disease risk and implications for prevention. Nutr. Bull. 2011, 36, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, Y.; Chen, G.-Y.; Wang, J.-B.; Sun, R. [Current situation analysis and supervision suggestions of traditional Chinese medicine health food claiming to enhance immune function]. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2019, 44, 885–890. [Google Scholar]

- Badaró, M. Alimentación saludable en Shanghái: Notas exploratorias. Salud Colect. 2016, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-T. When Chinese cuisine meets western wine. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2017, 7, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J. Análisis de las Conductas de Salud en la Población Inmigrante China Adulta de la Ciudad de Sevilla: Estudio Piloto. Master’s Thesis, Nuevas Tendencias Asistenciales y de Investigación en Ciencias de la Salud, Faculty of Nursing, Physiotherapy and Podiatry, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, G. Food, eating behavior, and culture in Chinese society. J. Ethn. Foods 2015, 2, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.X.; Wang, X.L.; Leong, P.M.; Zhang, H.M.; Yang, X.G.; Kong, L.Z.; Zhai, F.Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Guo, J.S.; Su, Y.X. New Chinese dietary guidelines: Healthy eating patterns and food-based dietary recommendations. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 27, 908–913. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, W.C.; Lau, K.H.K.; Matsumoto, M.; Moghazy, D.; Keenan, H.; King, G.L. Improvement of Insulin Sensitivity by Isoenergy High Carbohydrate Traditional Asian Diet: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Feasibility Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benazizi, I.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Ortíz-Moncada, R.; Martínez-Martínez, J.M. Influence of Employment Conditions and Length of Residence on Adherence to Dietary Recommendations in Immigrant Workers in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmboe-Ottesen, G.; Wandel, M. Changes in dietary habits after migration and consequences for health: A focus on South Asians in Europe. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, P.; Jurado, L.-F. Dietary Acculturation among Filipino Americans. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 13, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, P. Traditional Chinese Medicine, Food Therapy, and Hypertension Control: A Narrative Review of Chinese Literature. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2016, 44, 1579–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Liang, X. Food therapy and medical diet therapy of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Clin. Nutr. Exp. 2018, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Fei, Y.; Zhou, B.; Zheng, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, L.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, J.; et al. The Difference in Nutrient Intakes between Chinese and Mediterranean, Japanese and American Diets. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4661–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urpi, M.V. Chinese immigrants’ attitudes and perceptions towards communication in public services: Examples from the Catalan context. Leng. Migr. 2014, 6, 5–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A.; Brann, L. Influence of Cultural Beliefs on Infant Feeding, Postpartum and Childcare Practices among Chinese-American Mothers in New York City. J. Community Health 2014, 40, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.C.; Suchday, S.; Wylie-Rosett, J. Perceived Social Support, Coping Styles, and Chinese Immigrants’ Cardiovascular Responses to Stress. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2012, 19, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Male M (SD) | Female M (SD) | Total M (SD) | Statistics p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.1 (7.2) | 29.2 (7.4) | 30.7 (7.6) | U = 1457.5 p = 0.003 |

| Years residing in Spain | 12.7 (5.7) | 10.4 (5.5) | 11.3 (5.7) | U = 4774.5 p = 0.017 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | 51 (38.3) | 82 (61.7) | 133 (100) | − |

| Marital status Single Married Living with a partner (not married) Divorced | 11 (21.5) 36 (70.6) 3 (5.9) 1 (2.0) | 34 (41.5) 46 (56.1) 2 (2.4) 0 (0.0) | 45 (33.8) 82 (61.7) 5 (3.8) 1 (0.8) | χ2 = 7.35 p = 0.062 |

| Level of education Secondary or lower Vocational or university | 41 (80.4) 10 (19.6) | 62 (75.6) 20 (24.4) | 103 (77.4) 30 (22.6) | χ2 = 0.41 p = 0.521 |

| Employment status Employed Unemployed | 50 (98.0) 1 (2.0) | 78 (95.1) 4 (4.9) | 128 (96.2) 5 (3.8) | χ2 = 0.74 p = 0.649 |

| Theme | Category | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

| Food patterns | Differences between Chinese food and Western food | (C-95 woman, 40 years) “We like Spanish food but it’s as if you like Chinese food. You cannot eat Spanish food every day. Your stomach does not allow it”. (C-12 man, 21 years) “A different way used to preserve food is to dehydrate and even salt them”. (C-100 woman, 25 years) “Not much oil is used as in Spain. We eat some churros very similar to those here, but with less oil, much less [It is referred to “Youtiao”, a fried bread sticks widely used for breakfast. Unlike the Spanish churro that is sweet, the Chinese is salty]. |

| Products and dishes consumedby Chinese immigrants | (C-5 man, 35 years) “The food is totally Chinese from the beginning of the day. We usually have boiled rice or noodle soup for breakfast”. (C-78 woman, 22 years) “We eat vegetables daily and sometimes sauté them with meat in small pieces: chicken, pork, veal”. (C-50 man, 43 years) “Among fish, we like a lot sole or turbot and among the vegetables, we usually use zucchini, onion, and broccoli. The rest are all Chinese vegetables, such as pak choi”. (C-85 man, 37 years) “Chinese people eat many eggs (sometimes eat 2–3 boiled eggs), even for breakfast. When they go on a trip, as they do not have bread in their culture and they cannot make sandwiches, it is normal to eat canned noodles and sometimes they take cooked eggs”. (C-121 woman, 25 years) “The huo guo is very traditional, especially in winter. It is like a pan on fire where we put everything: meat, ball, and vegetables. Everything is boiled; we put sauce on it, sometimes spicy”. | |

| Modification of eating habits | (C-63 woman, 22 years) “I usually have Spanish breakfast, milk with cereals since I work very early and I don’t have time to prepare an authentic Chinese breakfast. To do this it would need at least an hour [to cook the rice soup and eat it]”. (C-6 man, 39 years) “I can only eat if we take turns at work, because the store cannot be left alone at any time”. (C-128 woman, 32 years) “You can see Chineses eating inside the stores or crouching at the door of the store. They are working and cannot close the business to eat”. | |

| Traditional foods mentioned by the participants | ||

| Figure 1 | Zongzi | Triangle shaped dumplings filled as white rice or yellow rice (a form of millet), served dotted with sweetened dates. In Zhejiang province, Jiaxing zongzi is stuffed with marinated ham and wrapped with a leaf. |

| Figure 2 | Chop suey | It is a dish of Chinese–American origin that literally means "mixed pieces." It usually consists of meats (chicken, beef, shrimp, or pork), cooked in a wok with vegetables such as celery, peppers, green beans, among others. It is served with steamed white rice. |

| Figure 3 | Tāngyuán | Tāngyuán are sweet glutinous rice balls, sugar, and almonds. The Chinese New Year celebration ends on the fifteenth lunar day (yuán xiāo jié), known worldwide as the Lantern Festival. Some traditions of this day are to appreciate colorful lanterns through the streets and eat with the family the sweet soup of tāngyuán. Having a round and compact shape, it symbolizes the strong family union. It is also consumed as a dessert at Chinese weddings, and at the Winter Solstice Festival (Dōngzhì). |

| Figure 4 | Qingmingguo | Qingmingguo is a traditional snack eaten on China Tomb Sweeping Day, also known as the Qingming Festival. It is mainly made up of Gnaphalium affine or Jersey Cudweed, a kind of medicinal plant mixed with glutinated rice flour, normally filled with pork, mushrooms, carrots, douya, doufu, and others. |

| Figure 5 | Yuebing | Moon cakes (yuebing) are traditional snacks eaten during the Zhongqiujie or Mid-Autumn Festival, the second largest festival in China. They are filled with soybean red bean paste, lotus seeds with a salted duck egg or nuts. Its roundness represents family reunion, that is, complete happiness and satisfaction. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Badanta, B.; de Diego-Cordero, R.; Tarriño-Concejero, L.; Vega-Escaño, J.; González-Cano-Caballero, M.; García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M.Á.; Lucchetti, G.; Barrientos-Trigo, S. Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain. Nutrients 2021, 13, 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030766

Badanta B, de Diego-Cordero R, Tarriño-Concejero L, Vega-Escaño J, González-Cano-Caballero M, García-Carpintero-Muñoz MÁ, Lucchetti G, Barrientos-Trigo S. Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain. Nutrients. 2021; 13(3):766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030766

Chicago/Turabian StyleBadanta, Bárbara, Rocío de Diego-Cordero, Lorena Tarriño-Concejero, Juan Vega-Escaño, María González-Cano-Caballero, María Ángeles García-Carpintero-Muñoz, Giancarlo Lucchetti, and Sergio Barrientos-Trigo. 2021. "Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain" Nutrients 13, no. 3: 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030766

APA StyleBadanta, B., de Diego-Cordero, R., Tarriño-Concejero, L., Vega-Escaño, J., González-Cano-Caballero, M., García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M. Á., Lucchetti, G., & Barrientos-Trigo, S. (2021). Food Patterns among Chinese Immigrants Living in the South of Spain. Nutrients, 13(3), 766. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030766