Comparing Assessment Tools as Candidates for Personalized Nutritional Evaluation of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Compare the capacity to identify nutritional risk/malnutrition in the nursing home elders.

- Evaluate the time spent for each tool.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

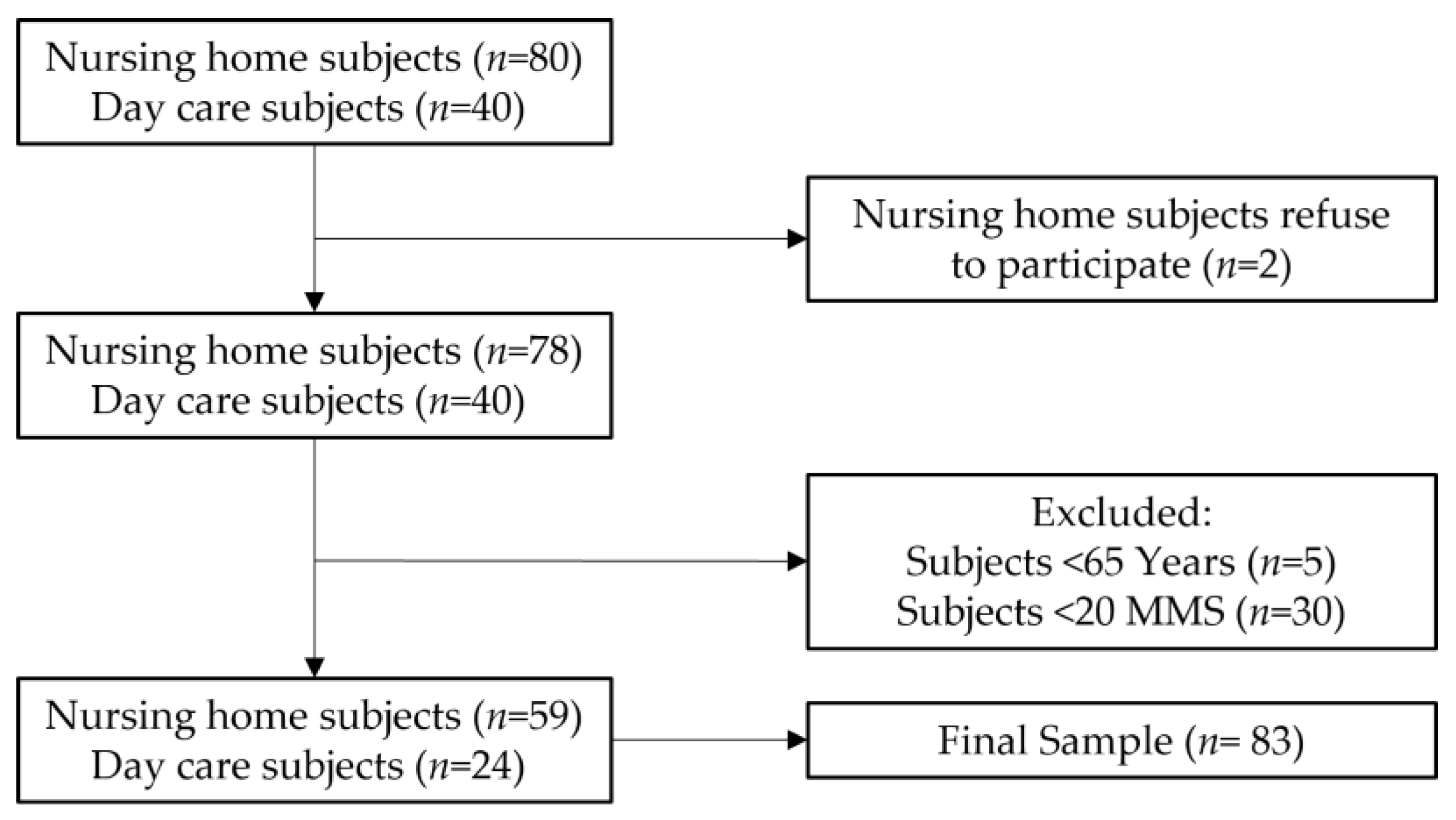

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.3. Ethics and Procedures

2.4. Anthropometric Parameters

2.5. Nutritional Screening and Assessment

2.5.1. Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF)

2.5.2. Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST)

2.5.3. Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS 2002)

2.5.4. Calf Girth (CG)

2.5.5. Subjective Global Assessment (SGA)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

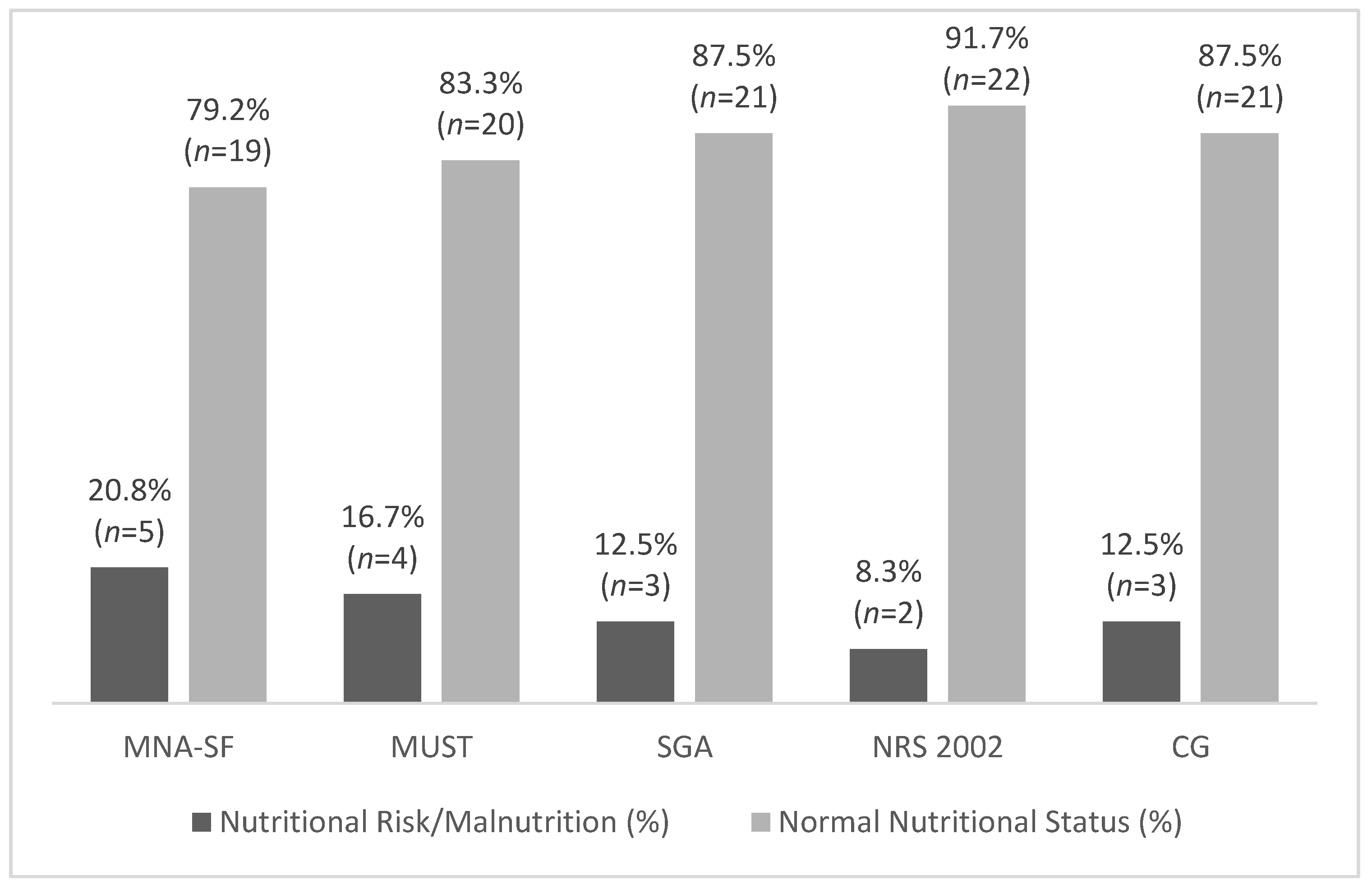

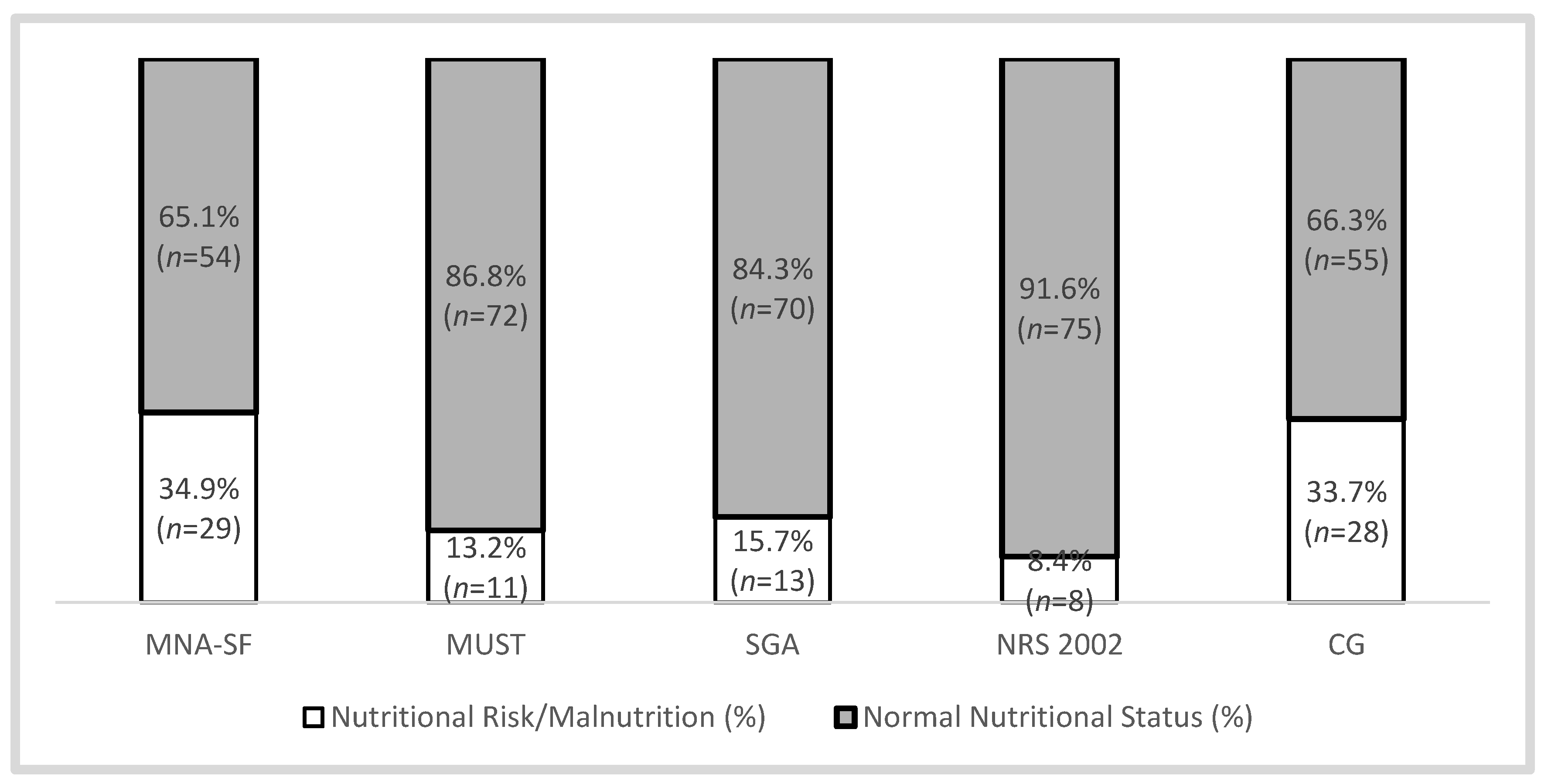

Characterization of Nutritional Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organizaton (WHO); US National Institute of Aging; National Institute of Aging; National Institute of Health. Global Health and Aging; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 2 October 2011).

- Vellas, B.; Villars, H.; Abellan, G.; Soto, M.E.; Rolland, Y.; Guigoz, Y.; Morley, J.E.; Chumlea, W.; Salva, A.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; et al. Overview of the MNA-Its history and challenges. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2006, 10, 456–463; discussion 463–465. [Google Scholar]

- Kondrup, J. ESPEN Guidelines for Nutrition Screening 2002. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, Y.; Lauwers-Cances, V.; Cournot, M.; Nourhashémi, F.; Reynish, W.; Rivière, D.; Vellas, B.; Grandjean, H. Sarcopenia, Calf Circumference, and Physical Function of Elderly Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton, R.J.; King, C.L.; Stroud, M.A.; Jackson, A.A.; Elia, M. Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool Predicts Mortality and Length of Hospital Stay in Acutely Ill Elderly. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Detsky, A.S.; McLaughlin, J.R.; Baker, J.P.; Johnston, N.; Whittaker, S.; Mendelson, R.A.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral. Nutr. 1987, 11, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sanford, A.M.; Morley, J.E.; Berg-Weger, M.; Lundy, J.; Little, M.O.; Leonard, K.; Malmstrom, T.K. High Prevalence of Geriatric Syndromes in Older Adults. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leão, L.L.; Engedal, K.; Monteiro-Junior, R.S.; Tangen, G.G.; Krogseth, M. Malnutrition Is Associated with Impaired Functional Status in Older People Receiving Home Care Nursing Service. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanini, M.; Catania, G.; Ripamonti, S.; Watson, R.; Romano, A.; Aleo, G.; Timmins, F.; Sasso, L.; Bagnasco, A. The WeanCare nutritional intervention in institutionalized dysphagic older people and its impact on nursing workload and costs: A quasi-experimental study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2620–2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulia, K.-A.; Yannakoulia, M.; Karageorgou, D.; Gamaletsou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Sipsas, N.V.; Zampelas, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Six Nutritional Screening Tools to Predict Malnutrition in the Elderly. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L.M.; Stephan, B.C.M.; Rosano, A.; Molfino, A.; Poggiogalle, E.; Lenzi, A.; Siervo, M.; Muscaritoli, M. What Are the Risk Factors for Malnutrition in Older-Aged Institutionalized Adults? Nutrients 2020, 12, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.; Marfell-Jones, M.; Olds, T.; de Ridder, H. International Standards for Anthropometric Assessment (ISAK); International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rizka, A.; Indrarespati, A.; Dwimartutie, N.; Muhadi, M. Frailty among Older Adults Living in Nursing Homes in Indonesia: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2021, 25, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strube-Lahmann, S.; Müller-Werdan, U.; Norman, K.; Skarabis, H.; Lahmann, N.A. Underweight in Nursing Homes: Differences between Men and Women. Gerontology 2021, 67, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, M.J.; Villafranca, J.M.S.; Ruiz, C.P.; Llata, M.J.T.; Lavin, G.L.; Ugalde, P.C.; Calderón, M.I.G.; Villoslada, M.J.C.; Pelaz, M.R.D.R.; González, A.I.B.; et al. Estudio Del Estado Nutricional de Los Ancianos de Cantabria. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kostecka, M.; Bojanowska, M. An Evaluation of the Nutritional Status of Elderly with the Use of the MNA Questionnaire and Determination of Factors Contributing to Malnutrition: A Pilot Study. Rocz. Państwowego Zakładu Hig. 2021, 72, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazemi, L.; Skoog, I.; Karlsson, I.; Hosseini, S. Malnutrition, Prevalence and Relation to Some Risk Factors among Elderly Residents of Nursing Homes in Tehran, Iran. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doumit, J.H.; Nasser, R.N.; Hanna, D.R. Nutritional and Health Status among Nursing Home Residents in Lebanon: Comparison across gender in a National cross-sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bauer, J.; Capra, S.; Ferguson, M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pablo, A.R.; Izaga, M.A.; Alday, L.A. Assessment of Nutritional Status on Hospital Admission: Nutritional Scores. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 57, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Nutritional Assessment Tool | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MNA-SF | MUST | SGA | NRS 2002 | CG | |

| Normal Nutritional Status | 12 to 14 | 0 | A | 0 to 2 | ≥31 |

| Nutritional Risk/Malnutrition | 0 to 11 | ≥1 | B and C | ≥3 | <31 |

| MNA-SF | MUST | SGA | NRS2002 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUST | 0.38 * | |||

| SGA | 0.45 * | 0.71 * | ||

| NRS2002 | 0.32 * | 0.65 * | 0.59 * | |

| CG | 0.49 * | 0.40 * | 0.46 * | 0.24 ** |

| Average Time (± SD) | MNA-SF | MUST | SGA | NRS 2002 | CG |

| 2 min (±0.52) | 3 min (±0.85) | 9 min (±1.14) | 3 min (±0.57) | 40 s (±2.64) |

| Kendall’s Mean Rank | MNA-SF | MUST | SGA | NRS 2002 | CG |

| 3.35 | 2.81 | 2.87 | 2.66 | 3.32 | |

| Kendall’s W | 0.15 * |

| OR (p-value) Age | MNA-SF | MUST | SGA | NRS 2002 | CG |

| 0.999 (0.980) | 1.015 (0.729) | 1.032 (0.445) | 1.048 (0.427) | 0.983 (0.551) | |

| Sex (Female) | 0.325 (0.172) | 1.417 (0.648) | 1.882 (0.391) | 2.556 (0.417) | 1.035 (0.950) |

| MMS | 0.829 (0.232) | 0.811 (0.359) | 0.811 (0.315) | 0.952 (0.866) | 0.814 (0.175) |

| Group (Day Center) | 0.325 (0.049) * | 1.216 (0.794) | 0.563 (0.463) | 1.253 (0.824) | 0.146 (0.008) * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa-Catita, D.; Bernardo, M.A.; Santos, C.A.; Silva, M.L.; Mascarenhas, P.; Godinho, C.; Fonseca, J. Comparing Assessment Tools as Candidates for Personalized Nutritional Evaluation of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114160

Sousa-Catita D, Bernardo MA, Santos CA, Silva ML, Mascarenhas P, Godinho C, Fonseca J. Comparing Assessment Tools as Candidates for Personalized Nutritional Evaluation of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home. Nutrients. 2021; 13(11):4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114160

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa-Catita, Diogo, Maria Alexandra Bernardo, Carla Adriana Santos, Maria Leonor Silva, Paulo Mascarenhas, Catarina Godinho, and Jorge Fonseca. 2021. "Comparing Assessment Tools as Candidates for Personalized Nutritional Evaluation of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home" Nutrients 13, no. 11: 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114160

APA StyleSousa-Catita, D., Bernardo, M. A., Santos, C. A., Silva, M. L., Mascarenhas, P., Godinho, C., & Fonseca, J. (2021). Comparing Assessment Tools as Candidates for Personalized Nutritional Evaluation of Senior Citizens in a Nursing Home. Nutrients, 13(11), 4160. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13114160