Abstract

Intestinal microbiota has been shown to be a potential determining factor in the development of obesity. The objective of this systematic review is to collect and learn, based on the latest available evidence, the effect of the use of probiotics and synbiotics in randomized clinical trials on weight loss in people with overweight and obesity. A search for articles was carried out in PubMed, Web of science and Scopus until September 2021, using search strategies that included the terms “obesity”, “overweight”, “probiotic”, “synbiotic”, “Lactobacillus”, “Bifidobacterium” and “weight loss”. Of the 185 articles found, only 27 complied with the selection criteria and were analyzed in the review, of which 23 observed positive effects on weight loss. The intake of probiotics or synbiotics could lead to significant weight reductions, either maintaining habitual lifestyle habits or in combination with energy restriction and/or increased physical activity for an average of 12 weeks. Specific strains belonging to the genus Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium were the most used and those that showed the best results in reducing body weight. Both probiotics and synbiotics have the potential to help in weight loss in overweight and obese populations.

1. Introduction

The Western Diet, characterized by a large consumption of processed products, saturated fats, sugars and a low fiber content, together with an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, has generated tripled levels of obesity in the world as compared to the year 1975, according to the World Health Organization [1]. In fact, obesity is currently classified as an epidemic and has become one of the greatest public health challenges in the twenty-first century [2].

Obesity is defined as an excessive accumulation of fat and hypertrophy of adipose tissue [1]. It is a chronic pathology, where the fundamental cause is the imbalance between the calories consumed and those expended [3]. However, it is considered a multi-causal and complex disease influenced by factors intrinsic and extrinsic to the individual, such as environmental, genetic, neuronal, endocrine and behavioral components [3,4]. Furthermore, overweight and obesity are risk factors for other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus II, cardiovascular diseases and some types of cancer [3].

It has recently been shown that obesity and its association with other chronic non-communicable diseases are not only the result of genetic factors, eating habits or lack of physical activity; it has also been proven that the Intestinal Microbiota (IM) is an environmental factor in its development [5,6,7,8].

People with overweight or obesity have been shown to have a specific IM profile, characterized by dysbiosis (imbalance) and lower microbial diversity compared to people with normal weight [6,9]. In this sense, a decrease has been seen in some bacterial phyla, such as the relationship between Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes [10,11], with lower proportions of Bacteroidetes and higher proportions of Firmicutes than those from people without obesity [12]. This seems to facilitate energy extraction from the ingested food and increases energy storage in the host’s adipose tissue [7]. In addition, this altered microbiota also results in a suppressed production of fasting-induced adipose factor (Fiaf). This suppression leads to an increased storage of triglycerides in adipose tissue and a low release of hormones such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and the peptide YY (PYY), promoting food intake. Although research in humans is incipient, there are clear indications that the intestinal microbiota is important for maintaining homeostasis of energy metabolism [13,14,15].

The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) defines probiotics as “live microorganisms that, after ingestion in specific numbers, exert benefits for the health of the host” [16] and prebiotic as “a substrate that is selectively utilized by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit” [17]. A synbiotic, is defined as “a mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) used selectively by host microorganisms that confers a benefit to the health of the host” [18].

This systematic review evaluates the effect of probiotic and synbiotic intake on IM in reducing body weight and/or body fat in apparently healthy people with overweight or obesity in randomized clinical trials.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was reported according to the PRISMA statement [19].

2.1. Search Strategy

In order to address the proposed objective, a systematic review has been carried out, finishing in September 2021 in three health science databases (Pubmed, Web of Science and Scopus).

Searching strategies were constructed using controlled language from the Medical Subject Headlines (MeSH) (Probiotics, Lactobacillus, Synbiotics, Overweight, Obesity, Weight Loss) and health science descriptors (DeCs) (Probiotic *, Lactobacillus, Synbiotic *, Overweight, Obesity, Weight loss, Bifidobacteria). Additionally, to define the union between the terminologies, the Boolean operators “AND”, “OR” and “NOT” were used. The truncation (*) was also used in order to encompass all words related to probiotic, and synbiotic.

To further delimit the results, additional filters were applied to each database. The specific details of the aforementioned strategies are given in Table S1.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The selection criterion were randomized clinical trials carried out in humans, published in the last 10 years, in apparently healthy people classified as overweight or obese, according to Body Mass Index (BMI; overweight 25–29.9 kg/m2, obese ≥ 30 kg/m2), body fat percentage (females: overweight 26.0–31.9%, obese ≥ 32%; males: overweight 21.0–24.9%, obese ≥ 25%), visceral fat area or waist circumference (obese females ≥ 80 cm, obese males ≥ 94 cm) [20,21] in all age groups, where it was evaluated the effect of taking a probiotic or synbiotic on weight loss. The published results of the study required to be written in English. Review articles, studies of people with other chronic non-communicable diseases, carried out on animals, in pregnant participants or in the breastfeeding stage were excluded. The selection process can be found in Section 3.1.

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

Data was extracted by one of the authors (VA-A) and contrasted with the other co- author (SM-P). From each selected publication, information about the name of the main author, year and place where the study was carried out, population characteristics, study design, intervention, comparison, strains and doses used, period of intervention and main results were extracted.

2.4. Quality Assessment

To assess the quality of the 27 studies included in the systematic review, the Jadad scale [22] was used. It consists of 5 questions related to methodological quality. The following criteria are evaluated: whether the trial is randomized and double blind, whether a description of exclusions and dropouts is detailed, and finally if the randomization and double blind method are adequate. A score of 5 points correspond to the maximum quality level, whereas a score < 3 points is considered to indicate poor quality.

3. Results

3.1. Selection Process

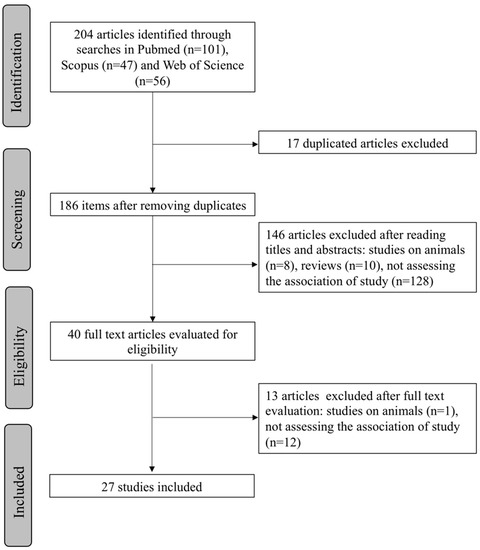

Based on the search carried out, a total of 204 articles (101 Pubmed, 47 Scopus, 56 Web of Science) were obtained using the strategy previously described. From the initial search results, 17 duplicate articles were discarded. After screening of the titles and abstracts of the remaining studies, 146 articles not meeting the eligibility criteria (8 studies carried out on animals, 10 reviews, 128 studies not assessing the association of our study) were excluded. From the 40 articles that were read in their entirety, 13 did not meet the selection criteria (1 study carried out on animals, 12 studies not assessing the association of our study) and were also discarded. Finally, 27 articles were included in this systematic review. A flow chart illustrating the selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart showing the process of article selection.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the collection of the selected studies in an orderly and summarized manner, including the country, author or authors, methodological design, intervention and a summary of the main results.

Table 1.

Detailed summary of the selected studies included in the revision.

The articles came from different countries, the majority being from Asia, where the most prevalent countries were Iran, South Korea and Japan. The second most prevalent countries were from the European continent, including Spain [39,42], Bulgaria [43,48] and Turkey [31]. The remaining countries were the United States [47], Canada [24,25] and Brazil [35]. From the 27 selected studies, 24 were conducted in adult populations and three in children [26,31,37]. Most of the studies considered both sexes, with the exceptions of [29,35,44,50], which were conducted in female only. The average age of the people included in the trials was 31.1 years, and the average BMI was 30.5 kg/m2.

Regarding the typology of the selected articles, they all had a quantitative approach, being randomized controlled clinical trials. Although most of the studies were double-blind, we found also single [31,42,44,47,50] and triple blind [26] studies. The most of the selected articles used probiotics except seven studies which investigated the effect of synbiotics [26,31,37,41,42,47,51]. Intervention duration average was 12 weeks, being 1 week the minimum [31] and 36 weeks the maximum [48] duration. Finally, the minimum sample size included 20 subjects [47] and the maximum, 225 [43].

Regarding the probiotic bacteria used in both probiotics and synbiotics, the genus Lactobacillus standed out, which included strains from the species L. rhamnosus, L. gasseri, L. plantarum, L. casei, L. lactis, L. acidophilus, L. delbrueckii, L. reuteri and L. curvatus. Regarding Bifidobacterium, it was common the use of strains belonging to the species B. animalis, B. bifidum, B. lactis and B. breve.

Probiotics and synbiotics were administered mainly through capsules, but also powders [30,31,34,49] and food products, mainly fermented dairy products such as probiotic yogurts [24,34,36,50] or fermented milks [27].

From the 27 studies, 11 combined the intervention with probiotics/synbiotics with other weight-loos strategies [25,28,29,36,37,38,42,44,47,48,50]. These combinations were successful in all of them but in two [33,47], which did not find significant differences. From the studies using either probiotics or synbiotics as unique intervention, only one did not find significant effects [24].

3.3. Probiotic Strains, Daily Doses and Total Intervention Doses

Most of the studies using fermented foods for the intake of probiotics contained lactic acid bacteria (LAB) as starter cultures, coming from the genus Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium mainly.

On the other hand, we found a great diversity in terms of probiotic species and strains used to treat overweight and/or obesity. Most of the studies reported the probiotic/symbiotic formulations at the strain level, either using multi-strains [29,30,33,40,44,45,47,48,52] or, single- strain [23,25,27,34,36,38,39,46,49,51] in their formulations.

When used as single-strain, all probiotic interventions showed positive effects in decreasing body weight, BMI, waist circumference, body fat mass or fat percentage. These strains belonged to the genera Lactobacillus (L. rhamnosus CGMCC1.3724 (LPR) [25], L. gasseri BNR17 [38], L.gasseri SBT2055 [27], L. sakei CJLS03 [46] and L. plantarum Dad-13 [49]), Bifidobacterium (B. lactis Bb-12 [36], B. animalis ssp. Lactis 420 (B420) [51], B. animalis CECT8145 [39]) and Pediococcus (Pediococcus pentosaceus LP28 [34]).

The multi-strain combinations were multiple and are detailed in Table 1.

The probiotic amount and duration of the intervention studies varied, from a maximum dose of 5 × 1010 [19,20] and the minimum dose of 1 × 106 [24], and from 4 [21] to 36 [20] weeks, respectively.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Table S2 shows the evaluation of the methodological quality of the 27 randomized clinical trials included in this systematic review, carried out using the Jadad scale. A total of seven studies were rated with poor methodological quality [31,37,42,44,46,47,50] (<3 points), and six studies obtained an acceptable score [23,24,26,27,28,29,36] (3 or 4 points). The remaining studies obtained the maximum score (5 points). Most of the studies clearly described the method of randomization used in the study, as well as the blinding procedure. Others, however, did not explain the method of allocation concealment or blinding, and some were not defined as double-blind randomized trials, thus scoring lower.

4. Discussion

In recent years, the effect of pre- and probiotics has gained a great deal of interest in the treatment of overweight and obesity. The results of this systematic review indicate that probiotics and synbiotics, whether used as single-strain or multi-strain, could have a favorable effect on weight loss and other related anthropometric markers in people with overweight or obesity. In particular L. gasseri [23,27], different strains of L. acidophilus alone or together with different strains of the genera Bifidobacterium [31,43,48] or Lactobacillus [30,40] showed reducing effects even when the participants did not undergo energy restriction; however these interventions had in common an intervention period ≥ 8 weeks.

Trials finding positive results also at anthropometric level combined part or all of the intervention with a hypocaloric diet, calorie restriction, and/or increased physical activity. Consequently, weight loss was not assigned solely to the effect of the probiotic. Therefore, the real results of the strain(s) used in these trials are somewhat biased, especially in those trials where the interventions were very short (4 weeks) [21].

Studies with L. gasseri showed a decrease in body weight [27], BMI [23,27], waist circumference [23,27,38] and areas of visceral [23,27] and subcutaneous fat [23]. High body mass has been reported to be strongly associated with risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in both childhood and adulthood [53,54]. L. gasseri BNR17 was associated with a decrease in visceral adipose tissue in waist and hip circumferences post-consumption [38]. In another trial carried out in adults with diabetes with the same strain, only a slight reduction was observed (without being significant) in body weight and waist circumference; a result possibly associated with the sample size [55]. Kadooka et al. [27] used L. gasseri SBT2055 and observed a decrease in visceral fat area, BMI and waist and hip circumference at doses of 106 CFU/g. When the same authors [23] used the same probiotic strain in a higher dose, observed also a reduction in the abdominal subcutaneous fat area, which suggests that at lower doses this strain can reduce its effectiveness.

The probiotics L. curvatus HY7601 with L. plantarum KY1032 showed reductions in body weight, BMI and waist circumference [30], what reinforces previous results carried out in mice, where they showed a reduction in weight gain and accumulation of fat, through the modulation of the intestinal microbiota [56].

L. acidophilus in combination with L. casei and Bifidobacterium, maintaining the usual lifestyle of the participants, showed positive effects in reducing body weight [41]. Another study using L. acidophilus with B. infantis obtained the same results [57]. Some Lactobacillus species, including L. acidophilus, have been associated with weight gain, due to their limited ability to break down fructose or glucose [58]. However, some species of the genus Lactobacillus in combination with other probiotics seem to favor weight loss [29,30,31,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,48,51,59,60].

It is worth mentioning that the doses of probiotics were different between the included studies, the minimum dose being 106 and the maximum dose 5 × 1010 CFU. One of the main reasons for this variations in the doses may be the characteristics of each probiotic. Some strains are more resistant to storage, and the dosage can also vary depending on how it is administered, for example either in dairy products or via capsule [61].

Another important point is the duration of the studies, which ranged from 4 to 36 weeks. However, most of the studies showing positive effects presented an intervention duration of 12 weeks. Therefore, 12 weeks seems to be the trend to start observing positive effects on body weight and/or fat mass by using probiotics. It should be noted that a reduction of ≥5% in initial body weight in a period of 6 months is clinically relevant and this would be associated with a significant reduction in some cardiovascular risk factors such as a reduction in blood pressure, lipids and blood glucose [62]. In the trial of Michael et al. [48], 40% of the participants in the probiotic group achieved this reduction after 9 months of supplementation, without dietary limitations.

Probiotics and synbiotics have been proposed to exert a decrease in body weight through different mechanisms (reviewed by [63,64]). Probiotics help in the recovery of the tight junctions between epithelial cells, thus reducing intestinal permeability, preventing the translocation of bacteria and reducing inflammation derived from lipopolysaccharides (LPS). The reduction in inflammation leads to an increase in insulin sensitivity in the hypothalamus, which improves satiety. Additionally, increased concentrations of leptin in adipose tissue, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and pancreatic polypeptide (PPY) in the intestine leads to a reduction in food intake due to an increase in satiety [15]. Recently, oral microbiota has also been associated to the development of obesity due to its modulating effects on the intestinal microbiota [65,66] and could have had an effect in the some of the observed results, especially in those where the intervention implied the ingestion of fermented foods.

Despite the observed beneficial effects, probiotics and synbiotics are not yet considered an alternative strategy in the treatment of obesity, probably due to the lack of regulation of this market [67]. In fact, in these products essential details such as the type of strain—or its combinations when more than one used—, the number of microorganisms included, the treatment duration, the route of administration, the formulation or the shelf-life and storage conditions, are often missing. Consequently, medical providers and the public are faced with a plethora of probiotic products with not proved health claims. In fact, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has rejected all submitted health claims for probiotics so far. More evidence-based trials that support their use are needed, taking into account that even when evidence exists, not all probiotic products are equally effective for all disease prevention or treatment indications.

The present study had some limitations. First of all, in many of the studies the probiotic/synbiotic intervention was accompanied by dietary or physical activity interventions, which may have hidden the real effect of the probiotic strain(s) used. In addition, there were also variations in the populations included in the different studies regarding sex and age, which can introduce bias. The strengths of this study are that only randomized clinical trials were included in order to compilate the highest degree of evidence, conducted in otherwise healthy people with overweight or obesity in order to minimize biases. Additionally, the review includes recent studies and provides specific strains, doses and intervention times.

5. Conclusions

From the analyzed randomized clinical trials, this systematic review indicates that both probiotics and synbiotics, specifically certain strains of Lactobacillus gasseri, L. rhamnosus, L. plantarum, L. curvatus associated with other Lactobacillus species and/or with species from the Bifidobacterium genus, have the potential to aid in weight and fat mass loss in overweight and obese populations. There is still a need, though, for clinical trials, in order to state more accurate recommendations in terms of strains, doses and intervention times. It is also suggested to carry out studies in homogeneous populations in terms of sex and age. In addition to this, it would be ideal that future trials would be carried out in the absence of weight loss techniques (such as dietary recommendations for weight loss and physical activity programs), in order to evaluate the specific effect of the strain/s.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu13103627/s1, Table S1: Search strategies used for this systematic review, Table S2: Assessment of the methodological quality of the included clinical trials, using the Jadad scale.

Author Contributions

V.Á.-A. and S.M.-P. conceptualized the study and the search strategy design. V.Á.-A. performed the selection of articles appropriate for the study and undertook the review of those final clinical trials. S.M.-P. was involved in the supervision of V.Á.-A. All authors contributed to the writing and corrections of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, because the Systematic Review relies on retrieval and synthesis of data from existing approved human trials.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the Systematic Review relies on retrieval and synthesis of data from existing approved human trials.

Data Availability Statement

The publications analyzed for this systematic study can be accessed from their respective journals, whereby access restrictions may apply.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CFU | Colony Forming Unit |

| Fiaf | Fasting-induced adipose factor |

| GLP | Glucagon-like peptide |

| IM | Intestinal Microbiota |

| ISAPP | International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics |

| LAB | Lactic Acid Bacteria |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| PPY | Pancreatic polypeptide |

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovary Syndrome |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RCT-DB | Randomized Controlled Trial Double Blind |

| RCT-TB | Randomized Controlled Trial Triple Blind |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.M.; Aronne, L.J. Causes of obesity. Abdom. Radiol. 2012, 37, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: Global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- María Magdalena Farías, N.; Catalina Silva, B.; Jaime Rozowski, N. Microbiota Intestinal: Rol en Obesidad. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2011, 38, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Cantone, E.; Cassarano, S.; Tuccinardi, D.; Barrea, L.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A. Gut microbiota: A new path to treat obesity. Int. J. Obes. Suppl. 2019, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelakis, E.; Armougom, F.; Million, M.; Raoult, D. The relationship between gut microbiota and weight gain in humans. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cani, P.D.; Delzenne, N.M. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Energy Metabolism and Metabolic Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Chatelier, E.; Nielsen, T.; Qin, J.; Prifti, E.; Hildebrand, F.; Falony, G.; Almeida, M.; Arumugam, M.; Batto, J.-M.; Kennedy, S.; et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013, 500, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Million, M.; Maraninchi, M.; Henry, M.; Armougom, F.; Richet, H.; Carrieri, P.; Valero, R.; Raccah, D.; Vialettes, B.; Raoult, D. Obesity-associated gut microbiota is enriched in Lactobacillus reuteri and depleted in Bifidobacterium animalis and Methanobrevibacter smithii. Int. J. Obes. 2011, 36, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Mahowald, M.A.; Magrini, V.; Mardis, E.R.; Gordon, J.I. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 444, 1027–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Bäckhed, F.; Turnbaugh, P.; Lozupone, C.A.; Knight, R.D.; Gordon, J.I. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11070–11075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, P.J.; Arusi, E.; Vinik, A.I.; Johnson, D.A. The Role and Influence of Gut Microbiota in Pathogenesis and Management of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baothman, O.A.; Zamzami, M.A.; Taher, I.; Abubaker, J.; Abu-Farha, M. The role of Gut Microbiota in the development of obesity and Diabetes. Lipids Health Dis. 2016, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, B.M.; Saad, M.J.A. Influence of Gut Microbiota on Subclinical Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 986734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.B.; Flint, H.J.; Salminen, S.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, K.S.; Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Reimer, R.A.; Reid, G.; Verbeke, K.; Scott, K.P.; Holscher, H.D.; Azad, M.B.; Delzenne, N.M.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of synbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumuk, V.; Tsigos, C.; Fried, M.; Schindler, K.; Busetto, L.; Micic, D.; Toplak, H. European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. Obes. Facts 2015, 8, 402–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickey, R.A.; Bartuska, C.G.D.; Bray, F.W.G.; Callaway, M.C.W.; Davidson, F.T.E.; Feld, M.S.; Ferraro, M.T.R.; Hodgson, S.F.; Jellinger, F.S.P.; Kennedy, F.P.F.; et al. AACE/ACE Position Statement on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Obesity (1998 Revision). Endocr Pract. 1998, 4, 297–350. [Google Scholar]

- Jadad, A.R.; Moore, R.A.; Carroll, D.; Jenkinson, C.; Reynolds, D.J.M.; Gavaghan, D.J.; McQuay, H.J. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control. Clin. Trials 1996, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadooka, Y.; Sato, M.; Imaizumi, K.; Ogawa, A.; Ikuyama, K.; Akai, Y.; Okano, M.; Kagoshima, M.; Tsuchida, T. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 64, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, J.M.; Chan, Y.-M.; Jones, M.L.; Prakash, S.; Jones, P.J.H. Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus amylovorus as probiotics alter body adiposity and gut microflora in healthy persons. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M.; Darimont, C.; Drapeau, V.; Emady-Azar, S.; Lepage, M.; Rezzonico, E.; Ngom-Bru, C.; Berger, B.; Philippe, L.; Ammon-Zuffrey, C.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosusCGMCC1.3724 supplementation on weight loss and maintenance in obese men and women. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1507–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safavi, M.; Farajian, S.; Kelishadi, R.; Mirlohi, M.; Hashemipour, M. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on some cardio-metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese children: A randomized triple-masked controlled trial. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 64, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadooka, Y.; Sato, M.; Ogawa, A.; Miyoshi, M.; Uenishi, H.; Ogawa, H.; Ikuyama, K.; Kagoshima, M.; Tsuchida, T. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in fermented milk on abdominal adiposity in adults in a randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrati, M.; Salehi, E.; Nourijelyani, K.; Mofid, V.; Zadeh, M.J.H.; Najafi, F.; Ghaflati, Z.; Bidad, K.; Chamari, M.; Karimi, M.; et al. Effects of Probiotic Yogurt on Fat Distribution and Gene Expression of Proinflammatory Factors in Peripheral Blood Singlenuclear Cells in Overweight and Obese People with or without Weight-Loss Diet. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2014, 33, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Bose, S.; Seo, J.-G.; Chung, W.-S.; Lim, C.-Y.; Kim, H. The effects of co-administration of probiotics with herbal medicine on obesity, metabolic endotoxemia and dysbiosis: A randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, M.; Kim, M.; Kwak, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Ahn, Y.-T.; Sim, J.-H.; Lee, J.H. Supplementation with two probiotic strains, Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032, reduced body adiposity and Lp-PLA2 activity in overweight subjects. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 19, 744–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipar, N.; Aydogdu, S.D.; Yildirim, G.K.; Inal, M.; Gies, I.; Vandenplas, Y.; Dinleyici, E.C. Effects of synbiotic on anthropometry, lipid profile and oxidative stress in obese children. Benef. Microbes 2015, 6, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibberd, A.A.; Yde, C.C.; Ziegler, M.L.; Honoré, A.H.; Saarinen, M.T.; Lahtinen, S.; Stahl, B.; Jensen, H.M.; Stenman, L.K. Probiotic or synbiotic alters the gut microbiota and metabolism in a randomised controlled trial of weight management in overweight adults. Benef. Microbes 2019, 10, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madjd, A.; Taylor, M.A.; Neek, L.S.; Delavari, A.; Malekzadeh, R.; Macdonald, I.A.; Farshchi, H.R. Effect of weekly physical activity frequency on weight loss in healthy overweight and obese women attending a weight loss program: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higashikawa, F.; Noda, M.; Awaya, T.; Danshiitsoodol, N.; Matoba, Y.; Kumagai, T.; Sugiyama, M. Antiobesity effect of Pediococcus pentosaceus LP28 on overweight subjects: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.C.; De Sousa, R.G.M.; Botelho, P.B.; Gomes, T.L.N.; Prada, P.D.O.; Mota, J.F. The additional effects of a probiotic mix on abdominal adiposity and antioxidant Status: A double-blind, randomized trial. Obesity 2017, 25, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi-Sartang, M.; Bellissimo, N.; de Zepetnek, J.O.T.; Brett, N.R.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Fararouie, M.; Bedeltavana, A.; Famouri, M.; Mazloom, Z. The effect of daily fortified yogurt consumption on weight loss in adults with metabolic syndrome: A 10-week randomized controlled trial. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianifar, H.R.; Ahanchian, H.; Safarian, M.; Javid, A.; Farsad-Naeimi, A.; Jafari, A.; Kiani, M.A.; Dahri, M. Effects of Synbiotics on Anthropometric Indices of Obesity in Children: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 33, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yun, J.M.; Kim, M.K.; Kwon, O.; Cho, B. Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 Supplementation Reduces the Visceral Fat Accumulation and Waist Circumference in Obese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedret, A.; Valls, R.M.; Calderón-Pérez, L.; Llauradó, E.; Companys, J.; Pla-Pagà, L.; Moragas, A.; Martín-Luján, F.; Ortega, Y.; Giralt, M.; et al. Effects of daily consumption of the probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CECT 8145 on anthropometric adiposity biomarkers in abdominally obese subjects: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1863–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, M.R.; Ahire, J.J.; Jayanthi, N.; Tripathi, A.; Nanal, S. Effect of multi-strain probiotic (UB0316) in weight management in overweight/obese adults: A 12-week double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study. Benef. Microbes 2019, 10, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.; Sepandi, M.; Marx, W.; Moradi, S.; Parastouei, K. Clinical and psychological responses to synbiotic supplementation in obese or overweight adults: A randomized clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Repiso, C.; Hernández-García, C.; García-Almeida, J.M.; Bellido, D.; Martín-Núñez, G.M.; Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Alcaide-Torres, J.; Sajoux, I.; Tinahones, F.J.; Moreno-Indias, I. Effect of Synbiotic Supplementation in a Very-Low-Calorie Ketogenic Diet on Weight Loss Achievement and Gut Microbiota: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1900167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, D.R.; Jack, A.A.; Masetti, G.; Davies, T.S.; Loxley, K.E.; Kerry-Smith, J.; Plummer, J.F.; Marchesi, J.R.; Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.; et al. A randomised controlled study shows supplementation of overweight and obese adults with lactobacilli and bifidobacteria reduces bodyweight and improves well-being. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razmpoosh, E.; Zare, S.; Fallahzadeh, H.; Safi, S.; Nadjarzadeh, A. Effect of a low energy diet, containing a high protein, probiotic condensed yogurt, on biochemical and anthropometric measurements among women with overweight/obesity: A randomised controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 35, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.-J.; Han, K.; Lim, T.-J.; Lim, S.; Chung, M.-J.; Nam, M.H.; Kim, H.; Nam, Y.-D. Effect of probiotics on obesity-related markers per enterotype: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. EPMA J. 2020, 11, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Moon, J.H.; Shin, C.M.; Jeong, D.; Kim, B. Effect of Lactobacillus sakei, a Probiotic Derived from Kimchi, on Body Fat in Koreans with Obesity: A Randomized Controlled Study. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 35, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergeev, I.N.; Aljutaily, T.; Walton, G.; Huarte, E. Effects of Synbiotic Supplement on Human Gut Microbiota, Body Composition and Weight Loss in Obesity. Nutrients 2020, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael, D.R.; Davies, T.S.; Jack, A.A.; Masetti, G.; Marchesi, J.R.; Wang, D.; Mullish, B.H.; Plummer, S.F. Daily supplementation with the Lab4P probiotic consortium induces significant weight loss in overweight adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Mariyatun, M.; Manurung, N.E.P.; Hasan, P.N.; Therdtatha, P.; Mishima, R.; Komalasari, H.; Mahfuzah, N.A.; Pamungkaningtyas, F.H.; Yoga, W.K.; et al. Effect of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Dad-13 powder consumption on the gut microbiota and intestinal health of overweight adults. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madjd, A.; Taylor, M.A.; Mousavi, N.; Delavari, A.; Malekzadeh, R.; Macdonald, I.A.; Farshchi, H.R. Comparison of the effect of daily consumption of probiotic compared with low-fat conventional yogurt on weight loss in healthy obese women following an energy-restricted diet: A randomized controlled trial1. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenman, L.K.; Lehtinen, M.J.; Meland, N.; Christensen, J.E.; Yeung, N.; Saarinen, M.T.; Courtney, M.; Burcelin, R.; Lähdeaho, M.-L.; Linros, J.; et al. Probiotic With or Without Fiber Controls Body Fat Mass, Associated With Serum Zonulin, in Overweight and Obese Adults—Randomized Controlled Trial. EBioMedicine 2016, 13, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.P.; Tran, B.X.; Nguyen, C.T.; Van Vo, T.; Baker, P.R.A.; Dunne, M.P. Inter-partner violence during pregnancy, maternal mental health and birth outcomes in Vietnam: A systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 96, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gishti, O.; Gaillard, R.; Durmus, B.; Abrahamse, M.; Van Der Beek, E.M.; Hofman, A.; Franco, O.H.; De Jonge, L.L.; Jaddoe, V.W.V. BMI, total and abdominal fat distribution, and cardiovascular risk factors in school-age children. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 77, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, C.-J.; Wang, P.-W.; Chen, T.-Y. The relationship between regional abdominal fat distribution and both insulin resistance and subclinical chronic inflammation in non-diabetic adults. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.-P.; Lee, K.-M.; Kang, J.-H.; Yun, S.-I.; Park, H.-O.; Moon, Y.; Kim, J.-Y. Effect ofLactobacillus gasseriBNR17 on Overweight and Obese Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2013, 34, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.-Y.; Ahn, Y.-T.; Park, S.-H.; Huh, C.-S.; Yoo, S.-R.; Yu, R.; Sung, M.-K.; McGregor, R.A.; Choi, M.-S. Supplementation of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032 in Diet-Induced Obese Mice Is Associated with Gut Microbial Changes and Reduction in Obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, B.J.; Park, S.U.; Jang, Y.S.; Ko, S.H.; Joo, N.M.; Kim, S.I.; Kim, C.-H.; Chang, D.K. Effect of functional yogurt NY-YP901 in improving the trait of metabolic syndrome. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drissi, F.; Merhej, V.; Angelakis, E.; Kaoutari, A.E.; Carrière, F.; Henrissat, B.; Raoult, D. Comparative genomics analysis of Lactobacillus species associated with weight gain or weight protection. Nutr. Diabetes 2014, 4, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrati, M.; Shidfar, F.; Nourijelyani, K.; Mofid, V.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J.; Bidad, K.; Najafi, F.; Gheflati, Z.; Chamari, M.; Salehi, E. Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium BB12, and Lactobacillus casei DN001 modulate gene expression of subset specific transcription factors and cytokines in peripheral blood singlenuclear cells of obese and overweight people. BioFactors 2013, 39, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Farajian, S.; Safavi, M.; Mirlohi, M.; Hashemipour, M. A randomized triple-masked controlled trial on the effects of synbiotics on inflammation markers in overweight children. J. Pediatr. 2014, 90, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.N.; Sivieri, K.; Alegro, J.H.A.; Saad, S.M.I. Aspectos tecnológicos de alimentos funcionais contendo probióticos. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Farm. 2002, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the obesity society. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 2985–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloom, K.; Siddiqi, I.; Covasa, M. Probiotics: How Effective Are They in the Fight against Obesity? Nutrients 2019, 11, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerdó, T.; García-Santos, J.A.; Bermúdez, M.G.; Campoy, C. The Role of Probiotics and Prebiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benahmed, A.G.; Gasmi, A.; Doşa, A.; Chirumbolo, S.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Aaseth, J.; Dadar, M.; Bjørklund, G. Association between the gut and oral microbiome with obesity. Anaerobe 2021, 70, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radaic, A.; Kapila, Y.L. The oralome and its dysbiosis: New insights into oral microbiome-host interactions. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1335–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Simone, C. The Unregulated Probiotic Market. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).