Co-Design Practices in Diet and Nutrition Research: An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.1.1. Population

2.1.2. Intervention

2.1.3. Control or Comparator

2.1.4. Outcomes

2.1.5. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

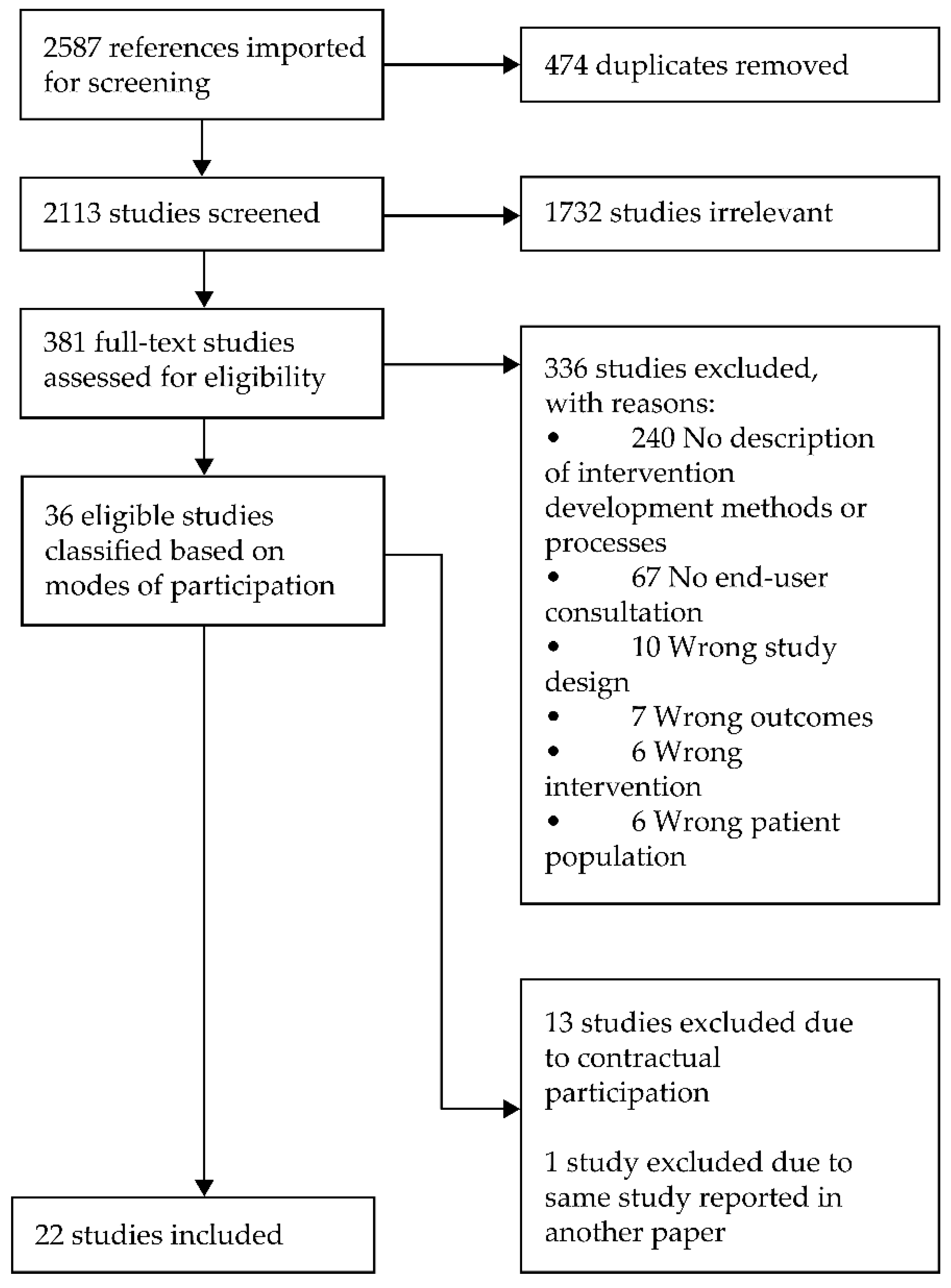

2.3.1. Selection of Studies

2.3.2. Classification of Studies Based on Modes of Participation

2.3.3. Data Extraction and Management

2.3.4. Sufficiency of Reporting

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.1.1. Country

3.1.2. Study Design

3.1.3. Participants

3.1.4. Other Stakeholders Involved in the Intervention Development Process

3.1.5. Theoretical Frameworks

3.1.6. Recruitment Methods

3.1.7. Participatory Design Methods and Processes

3.1.8. Extent of Participation

3.1.9. Data Analysis Methods

3.1.10. Intervention Effectiveness

3.1.11. Sufficiency of Reporting

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Considerations of the Included Research

4.2. The Effectiveness of Co-Design in Nutrition Research

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Review

4.4. Implications for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zobel, E.H.; Hansen, T.W.; Rossing, P.; von Scholten, B.J. Global changes in food supply and the obesity epidemic. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezzati, M.; Riboli, E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, S.; Minozzi, S.; Bellisario, C.; Mary Rose, S.; Susta, D. Effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving dietary behaviours among people at higher risk of or with chronic non-communicable diseases: An overview of systematic reviews. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 73, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, D. Global challenges and opportunities for dietitians. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 77, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, M.J.; Manalili, K.; Jolley, R.J.; Zelinsky, S.; Quan, H.; Lu, M. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018, 21, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, C. Public and patient participation in health policy, care and research. Porto Biomed. J. 2017, 2, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, H.; McKernon, S.; Mullin, B.; Old, A. Improving healthcare through the use of co-design. NZ Med. J. 2012, 125, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, E.B.-N.; Stappers, P.J. Co-creation and the new landscapes of design. Co-Design 2008, 4, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamenopoulos, T.; Alexiou, K. Co-Design as Collaborative Research; Bristol University/AHRC Connected Communities Programme: Bristol, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jessup, R.L.; Osborne, R.H.; Buchbinder, R.; Beauchamp, A. Using co-design to develop interventions to address health literacy needs in a hospitalised population. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, N.; Nava-Aguilera, E.; Arosteguí, J.; Morales-Perez, A.; Suazo-Laguna, H.; Legorreta-Soberanis, J.; Hernandez-Alvarez, C.; Fernandez-Salas, I.; Paredes-Solís, S.; Balmaseda, A.; et al. Evidence based community mobilization for dengue prevention in Nicaragua and Mexico (Camino Verde, the Green Way): Cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2015, 351, h3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Burke, K.; Halford, N.; Rothwell, K.; Darley, S.; Woodward-Nutt, K.; Bowen, A.; Patchwood, E. Value and learning from carer involvement in a cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation-Organising Support for Carers of Stroke Survivors (OSCARSS). Res. Involv. Engagem. 2020, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyles, H.; Jull, A.; Dobson, R.; Firestone, R.; Whittaker, R.; Te Morenga, L.; Goodwin, D.; Mhurchu, C.N. Co-design of mHealth delivered interventions: A systematic review to assess key methods and processes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, P.; Saeri, A.K.; Bragge, P. Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locock, L.; Boaz, A. Drawing straight lines along blurred boundaries: Qualitative research, patient and public involvement in medical research, co-production and co-design. Evid. Policy J. Res. Debate Pract. 2019, 15, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, M.K.; Burford, G.; Hoover, E. What is participation? Design leads the way to a cross-disciplinary framework. Des. Issues 2013, 29, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, A.; Jewkes, R. What is participatory research? Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 41, 1667–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, S.D. Resource-Poor Farmer Participation in Research: A Synthesis of Experiences from Nine National Agricultural Research Systems; Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bramer, W.M.; Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kleijnen, J.; Franco, O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: A prospective exploratory study. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutron, I.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Schulz, K.F.; Ravaud, P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: Explanation and elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 148, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, K.W.; Goldstein, M.; Kaplan, R.M.; Kaufmann, P.G.; Knatterud, G.L.; Orleans, C.T.; Spring, B.; Trudeau, K.J.; Whitlock, E.P. Evidence-based behavioral medicine: What is it and how do we achieve it? Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Burns, C.; Liebzeit, A.; Ryschka, J.; Thorpe, S.; Browne, J. Use of participatory research and photo-voice to support urban Aboriginal healthy eating. Health Soc. Care Community 2012, 20, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, S.; Park, S.; Dawda, P.; Burns, J. Participatory research design in mobile health: Tablet devices for diabetes self-management. Commun. Med. 2015, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gittelsohn, J.; Rosol, R.; Beck, L. Addressing the public health burden caused by the nutrition transition through the Healthy Foods North nutrition and lifestyle intervention programme. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chojenta, C.; Mingay, E.; Gresham, E.; Byles, J. Cooking for One or Two: Applying Participatory Action Research to improve community-dwelling older adults’ health and well-being. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2018, 29, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitzman-Ulrich, H.E.; Wilson, D.K.; Lyerly, J.E. Qualitative perspectives from African American youth and caregivers for developing the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss intervention. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2016, 4, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dongen, E.J.; Leerlooijer, J.N.; Steijns, J.M.; Tieland, M.; de Groot, L.C.; Haveman-Nies, A. Translation of a tailored nutrition and resistance exercise intervention for elderly people to a real-life setting: Adaptation process and pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, E.; Vyth, E.L.; Hoekstra, T.; Steenhuis, I.H. Nudging and social marketing techniques encourage employees to make healthier food choices: A randomized controlled trial in 30 worksite cafeterias in The Netherlands. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, E.; Vyth, E.L.; Steenhuis, I.H. Using nudging and social marketing techniques to create healthy worksite cafeterias in The Netherlands: Intervention development and study design. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velema, E.; Vyth, E.L.; Steenhuis, I.H. ‘I’ve worked so hard, I deserve a snack in the worksite cafeteria’: A focus group study. Appetite 2019, 133, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffileno, B.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Fogg, L.; Darmoc, R. Making behavior change interventions available to young African American women: Development and feasibility of an eHealth lifestyle program. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2015, 30, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ard, J.D.; Cox, T.L.; Zunker, C.; Wingo, B.C.; Jefferson, W.K.; Brakhage, C. A study of a culturally enhanced EatRight dietary intervention in a predominately African American workplace. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2010, 16, E1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zunker, C.; Cox, T.L.; Wingo, B.C.; Knight, B.N.; Jefferson, W.K.; Ard, J.D. Using formative research to develop a worksite health promotion program for African American women. Women Health 2008, 48, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito-Ashurst, I.; Perry, L.; Sanders, T.; Thomas, J.; Dobbie, H.; Yaqoob, M. Applying research in nutrition education planning: A dietary intervention for Bangladeshi chronic kidney disease patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Brito-Ashurst, I.; Perry, L.; Sanders, T.; Thomas, J.; Yaqoob, M.; Dobbie, H. Dietary salt intake of Bangladeshi patients with kidney disease in East London: An exploratory case study. e-SPEN Eur. e-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2009, 4, e35–e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- De Brito-Ashurst, I.; Perry, L.; Sanders, T.; Thomas, J.; Yaqoob, M.; Dobbie, H. Barriers and facilitators of dietary sodium restriction amongst Bangladeshi chronic kidney disease patients. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, A.D.S.; Castro, I.R.R.D.; Wolkoff, D.B. Impact of the promotion of fruit and vegetables on their consumption in the workplace. Rev. Saude Publica 2013, 47, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsson, E.; Johansson, K.; Eriksson, J.; Sundström, J.; Neovius, M.; Marcus, C. Weight loss and dropout during a commercial weight-loss program including a very-low-calorie diet, a low-calorie diet, or restricted normal food: Observational cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, T.L.; Van Pelt, R.E.; Anderson, M.A.; Daniels, L.J.; West, N.A.; Donahoo, W.T.; Friedman, J.E.; Barbour, L.A. A higher-complex carbohydrate diet in gestational diabetes mellitus achieves glucose targets and lowers postprandial lipids: A randomized crossover study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, T.L.; Van Pelt, R.E.; Anderson, M.A.; Reece, M.S.; Reynolds, R.M.; Becky, A.; Heerwagen, M.; Donahoo, W.T.; Daniels, L.J.; Chartier-Logan, C.; et al. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus randomized to a higher–complex carbohydrate/low-fat diet manifest lower adipose tissue insulin resistance, inflammation, glucose, and free fatty acids: A pilot study. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiel, S.; Bindels, L.B.; Pachikian, B.D.; Kalala, G.; Broers, V.; Zamariola, G.; Chang, B.P.; Kambashi, B.; Rodriguez, J.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Effects of a diet based on inulin-rich vegetables on gut health and nutritional behavior in healthy humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1683–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsson, L.R.; Friedrichsen, M.; Göransson, A.; Hallert, C. Impact of an active patient education program on gastrointestinal symptoms in women with celiac disease following a gluten-free diet: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2012, 35, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Song, H.-J.; Han, H.-R.; Kim, K.B.; Kim, M.T. Translation and validation of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension for koreans intervention: Culturally tailored dietary guidelines for Korean Americans with high blood pressure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2013, 28, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madjd, A.; Taylor, M.A.; Delavari, A.; Malekzadeh, R.; Macdonald, I.A.; Farshchi, H.R. Beneficial effect of high energy intake at lunch rather than dinner on weight loss in healthy obese women in a weight-loss program: A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 982–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosher, C.E.; Lipkus, I.; Sloane, R.; Snyder, D.C.; Lobach, D.F.; Demark-Wahnefried, W. Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START trial: Exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors’ maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psychooncology 2013, 22, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nybacka, Å.; Hellström, P.M.; Hirschberg, A.L. Increased fibre and reduced trans fatty acid intake are primary predictors of metabolic improvement in overweight polycystic ovary syndrome—Substudy of randomized trial between diet, exercise and diet plus exercise for weight control. Clin. Endocrinol. 2017, 87, 680–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudel, R.A.; Gray, J.M.; Engel, C.L.; Rawsthorne, T.W.; Dodson, R.E.; Ackerman, J.M.; Rizzo, J.; Nudelman, J.L.; Brody, J.G. Food packaging and bisphenol A and bis (2-ethyhexyl) phthalate exposure: Findings from a dietary intervention. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 914–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar, S.; Adznam, S.N.; Rahman, S.A.; Yusoff, N.A.; Yassin, Z.; Arshad, F.; Sakian, N.I.; Salleh, M.; Samah, A.A. Development and analysis of acceptance of a nutrition education package among a rural elderly population: An action research study. BMC Geriatr. 2012, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, J.; Biswas, T.; Adhikary, G.; Ali, W.; Alam, N.; Palit, R.; Uddin, N.; Uddin, A.; Khatun, F.; Bhuiya, A. Impact of mobile phone-based technology to improve health, population and nutrition services in Rural Bangladesh: A study protocol. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2017, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory. In Annals of Child Development. Vol. 6. Six Theories of Child Development; Vasta, R., Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1989; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, B.; Maar, M.; Manitowabi, D.; Moeke-Pickering, T.; Trudeau-Peltier, D.; Trudeau, S. The Gaataa’aabing Visual Research Method: A Culturally Safe Anishinaabek Transformation of Photovoice. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1609406919851635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Erueti, C.; Glasziou, P.P. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: Analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. BMJ 2013, 347, f3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasziou, P.; Meats, E.; Heneghan, C.; Shepperd, S. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ 2008, 336, 1472–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear-Smith, F.; Jackson, C.; Greenhalgh, T. Co-design and implementation research: Challenges and solutions for ethics committees. BMC Med. Ethics 2015, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Gopalan, R.; Berlin, J.; Matthews, D.R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991, 337, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasgow, R.E.; Vogt, T.M.; Boles, S.M. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, D.; Jones, F.; Harris, R.; Robert, G. What outcomes are associated with developing and implementing co-produced interventions in acute healthcare settings? A rapid evidence synthesis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.; Pekepo, C.; Corrigan, C.; Matoe, L.; Mules, R.; Goodwin, D.; Dymus, J.; Tunks, M.; Grey, J.; Humphrey, G.; et al. Co-designing an mHealth tool in the New Zealand Maori community with a “Kaupapa Maori” approach. AlterNative Int. J. Indig. Peoples 2018, 14, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borek, A.J.; Abraham, C.; Smith, J.R.; Greaves, C.J.; Tarrant, M. A checklist to improve reporting of group-based behaviour-change interventions. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Definition | Further Explanation | Eligible for Review | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collegiate (deepest form of participation) | Researchers and local people work together as colleagues with different skills to offer, in a process of mutual learning where local people have control over the process. | Deepest level of participation. Researcher’s role shifts from director to facilitator and catalyst. | √ |

| Collaborative | Researchers and local people work together on projects designed, initiated, and managed by researchers. | Collegiate techniques are applied but are influenced by institutional agendas. Genuine participation occurs within the confines of a larger, pre-designed research process. | √ |

| Consultative | People are asked for their opinions and consulted by researchers before interventions are made. | People are involved as informants for the purposes of verifying and amending research findings. | √ |

| Contractual (most shallow form of participation) | People are contracted into the projects of researchers to take part in their enquiries or experiments. | People are involved to fulfil a data collection role and they have no control or input into projects that are scientist-led, designed, and managed. | X |

| Concept 1: Co-Design | Concept 2: Dietary Intervention |

|---|---|

| co-design* OR codesign* OR co-creat* OR cocreat* OR “participatory design” OR “design research” OR “collective creativity” OR “user-centred design” OR design* OR “consumer participation” OR pre-design* OR participatory OR “participatory action research” OR “action research” OR “community-based participatory research” OR “co-production” OR “user-centred” OR “human-centred” OR “human-centred design” OR “design thinking” OR “experience based design” OR “experience-based design” OR “experience based co-design” OR “experience-based co-design” OR “experience based codesign” OR “experience-based codesign” | diet* OR nutrition* OR eat OR eating OR food* OR meal* OR “meal plan*” OR menu* adj1 intervention* OR activit* OR strateg* OR program* OR service* OR plan* OR advice OR regime* OR therap* OR provision |

| AND ⟶ | |

| Study Reference and Aim | Study Design, Participants and Other Stakeholders, Setting, and Time of Study | Intervention and Main Finding or Outcome | Theoretical Framework and Recruitment Method | Participation Method, Data Collection Techniques, Data Analysis Techniques | Research Stage at Participation Occurred | Quality Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al. (2012) [24]: To gain an understanding of Aboriginal people’s perspectives on food and food insecurity as an action research method to strengthen food programmes. | Study design: Qualitative (Participatory Action Research). Participants: Men and women (n = 10) in their twenties and thirties. Other stakeholders: N/A. Setting: Aboriginal community organisations located in regional Victoria, Australia. Time of study: 2009–2010. | Intervention: Ongoing community-based initiatives to address food security among Aboriginal Australians, including food vouchers. Main outcome: Existing programs adapted to reflect target community’s language, ways of knowing and local challenges or opportunities for healthy eating. | Theory: Core structures of Aboriginal ontology. Recruitment: Invitations through community organisation and health workers; Information session held at community organisation. | Participation method: Photo-voice method. Data collection techniques: Participants took photographs relating to food; focus group discussions; individual interviews for participants storytelling about most significant photographs. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess background knowledge and evidence, assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collegiate Standard of Reporting score: 6 |

| Burford et al. (2015) [25]: Utilise participatory design techniques to inform the design of a study that introduces mobile tablet devices in the self-management of type 2 diabetes in a primary healthcare setting. | Study design: Qualitative (Participatory Action Research). Participants: Research team members (n = 4); health professionals: general practitioners, specialist, nurses, practice manager (n = 11); patients (n = 30). Age of participants was not reported. Other stakeholders: N/A. Setting: A general practice super-clinic in Australia. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Mobile tablet devices for the in the self-management of type 2 diabetes in primary healthcare settings. Main outcome: the issue of six “invitations” to 28 people with diabetes to frame their use of a mobile tablet device in managing their health; clustered in themes “Empowered” and “Compelled”, representing typical patient attitudes and behaviours. | Theory: Agency model of customisation for users of new media technologies. Recruitment: Through GP Super Clinic. | Participation method: Facilitated design workshops. Co-design techniques: Examination of available m-health apps and websites, use of iPads to view m-health. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, assess user needs to inform technology. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collegiate Standard of Reporting score: 3 |

| Sharma et al. (2010) [26]: Describe Health Foods North Programme intervention development and outcomes. | Study design: Qualitative Participants: Inuit and Inuvialuit people (n unspecified). Age of participants was not reported. Other stakeholders: Staff from food retailers and local organisations (n unspecified). Setting: Community-based; Arctic regions of Nunavut and the NWT, Canada. Time of study: 2008–2009. | Intervention/main outcome: The development of Health Foods North, a culturally appropriate nutrition and physical activity environmental/health promotion intervention addressing chronic disease risk and dietary adequacy. | None reported. Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Posted advertisements and flyers. | Participation method: Interviews and workshops. Data collection techniques: In-depth interviews with community stakeholders, dietary assessment using 24-h recall to target foods for intervention programme, community workshops. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collegiate Standard of Reporting score: 1 |

| Chojenta et al. (2018) [27]: Describe the process of the redevelopment and expansion of Cooking for One or Two, a community-based nutrition education program for older adults. | Study design: Qualitative (focus groups). Participants: Community-dwelling older adults (n = 111). Age of participants was not reported. Other stakeholders: Health promotion experts (e.g., a Fellow of the Dietetic Association of Australia); media communication students. Setting: Community-based, large regional city in New South Wales, Australia. Time of study: 2011–2013. | Intervention: Australian-based cooking skills program with education sessions over 5 weeks teaching cooking skills and healthy behaviours while facilitating social interaction. Main outcome: Participants’ experiences informed a supplementary cookbook and education modules. Continued engagement with target group achieved. | Theory: Participatory Action Research (PAR) framework. Recruitment: Past participants and members from a research institute register were recruited. | Participation method: Three-stage iterative intervention development. Data collection techniques: Focus groups and expert consultation, iterative drafting and road-testing of recipe book, telephone interviews, focus group. Data analysis techniques: Not reported. | Develop intervention content, prototype testing, assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 5 |

| Kitzman-Ulrich et al. (2016) [28]: To gather opinions of parent and caregiver dyads on barriers and facilitators, motivators and preferences for a health and weight loss program from a social-ecological perspective. | Study design: Qualitative (Participatory Action Research). Participants: African American parents or caregivers (n = 30) with a mean age of 46.1 (SD = 9.8) years, young people (n = 25) with a mean age of 12.4 (SD = 1.1) years. Other stakeholders: Graduate students in psychology and public health. Setting: Family-based, South Carolina, USA. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Families Improving Together (FIT): a family- and Social Cognitive Theory- based weight loss intervention. Main outcome: Four main themes established relating to the development of the FIT intervention, e.g., using a positive health promotion framework for weight loss programs, social support. | Theory: Social Cognitive Theory. Recruitment: Through paediatric clinics and community-based organisations. | Participation method: Focus groups. Data collection techniques: Focus groups exploring Social Cognitive Theory predictors of weight loss. Data analysis techniques: Content analysis. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 5 |

| van Dongen et al. (2017) [29]: To adapt an existing experimental nutrition and exercise intervention for frail elderly people to a real-life setting; To test the feasibility and potential impact of this prototype intervention in the new setting. | Study design: Qualitative (Participatory Action Research). Participants: Dietitians and physiotherapists (n = 8); Interview participants from the original intervention (n = 13) and possible future participants (n = 9); Community-dwelling (n = 25) elderly ≥65 years (74.1 ± 6.8 years); healthcare professionals including dietitians, physiotherapists, coordinator (n = 7); focus group participants (n = 14). Other stakeholders: N/A. Setting: Community-based, Harderwijk, The Netherlands. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Nutrition and resistance-type exercise training intervention seeking to improve muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in (pre-)frail older adults. Main outcomes: Successful adaptation of the experimental intervention into real-life settings; intervention was perceived as highly acceptable. Adaptations mostly related to the design of training for implementing and recruiting professionals, design of a dietitian-guided nutrition programme, and organisation of the training sessions. | Theory: Intervention Mapping. Recruitment: Through community nurses from the care organisation and through local organisations and local newspaper ad. | Participation method: 6-stage intervention mapping process followed by pre–post pilot testing of intervention. Data collection techniques: Literature review, semi-structured interviews, focus groups, iterative discussion of findings, pre–post pilot study with interviews and focus groups. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, prototype testing, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 4 |

| Velema et al. (2018) [30]: To examine effects of a healthy worksite cafeteria (“worksite cafeteria 2.0”] intervention on food purchases. Related works: Velema et al. (2017), Velema et al. (2019) [31,32] | Study design: Randomised Controlled Trial. Participants: Primary outcome was sales data (unspecified n) from 30 cafeterias; 1651 employees. Age of participants was not reported. Other stakeholders: Expert interviews (n = 14) and seven focus groups (n = 45). Setting: Worksite cafeterias in The Netherlands. Time of study: 2016. | Intervention: Workplace cafeteria nutrition intervention seeking healthier purchases in the worksite cafeteria. Main finding: Significant, positive effects of the intervention on purchases for three of the seven studied product groups: healthier sandwiches, healthier cheese as a sandwich filling, and the inclusion of fruit. Increased sales of healthier meal options maintained through 12-week intervention. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Participants were recruited by clients (companies) catered by the partnered contract catering companies. | Participation method: Focus groups to inform intervention design. Data collection techniques: Focus groups. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess background knowledge and evidence, assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 5 |

| Staffileno et al. (2015) [33]: Describe process of adapting a face-to-To adapt a lifestyle change intervention from face-to-face to web-based. | Study design: Mixed methods. Participants: African American adults (18–45 years old) with pre-hypertension. Focus group and survey (n = 11); prototype testing (n = 8); beta testing (n = 8). Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: Rush University. Medical Center (hospital): USA. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: 24 eHealth learning modules that use interactive and situational learning technology. Includes 12 modules focused on Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) eating plan and 12 on lifestyle physical activity. Main finding/outcome: Successful transformation of face-to-face content into a Web-based platform. | Theory: Social Cognitive Theory; Self-directed behaviour change (behavioural self-management). Motivational coaching. Recruitment: Internet advertisement, print materials, and at blood pressure screenings. | Participation method: Iterative intervention development and pilot testing. Data collection techniques: Focus groups, intervention, development/conversion from face-to-face to eHealth modules, prototype testing in interactive workshop session, pilot testing. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, prototype testing, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 5 |

| Ard et al. (2010) [34]: Evaluate the effectiveness of a culturally enhanced ‘EatRight’ dietary intervention among African American women in a workplace setting. Related works: Zunker et al. (2008) [35] | Study design: Sequential, control to intervention cross-over design. Participants: Trial participants (n = 37) with baseline age of 47.5 (11.8) years Other stakeholders: African American women (n = 14) took part in focus groups to inform the research [35]. Setting: Workplace, USA. Time of study: 2006. | Intervention: Culturally modified EatRight Program, based on the concept of “time-calorie displacement”, with large quantities of high-bulk, low-energy-density foods and moderation in high-energy-density foods. Main finding/outcome: Intervention was associated with significant weight loss. Feasibility of the cultural adaptations was established. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Pay-check mailers and flyers distributed at headquarters and posted at worksites. | Participation method: Iterative intervention development and pilot testing. Data collection techniques: Nominal Group Technique group discussions, iterative intervention development. Data analysis techniques: Thematic analysis. | Assess background knowledge and evidence, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 5 |

| De Brito-Ashurst et al. (2013) [36]: Describe a theoretical approach to inform the development of a nutrition education programme for adult UK-Bangladeshi chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Related works: De Brito-Ashurst et al. (2009), De Brito-Ashurst et al. (2011) [37,38] | Study design: Descriptive Participants: Bengali origin, renal disease patients who participated in a program pilot (n = 6). Age of participants was not reported. Other stakeholders: Interpreters, Bengali key workers and local community dietitians; focus group participants (n = 20). Setting: East London. UK Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: 6-month, low-salt dietary behavioural programme consisting of multiple interactions with programme staff and fortnightly telephone calls to reinforce health message. Main outcome: Successful description of the intervention development process. | Theory: Intervention Mapping; PRECEDE model Recruitment: Not reported. | Participation method: Intervention mapping and PRECEDE approach. Data collection techniques: Literature review, focus groups Co-design data analysis techniques: Not reported. | Assess background knowledge and evidence, assess user needs to inform intervention focus. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 3 |

| Franco et al. (2013) [39]: To conduct impact evaluation of activities to promote fruit and vegetables (FV) consumption in the workplace. | Study design: Before-after. Participants: Workers who had lunch in the workplace cafeteria during the study, n = 197 (mean age = 40 (8.3) years). Other stakeholders: Concessionaire owner and nutritionist. Setting: workplace in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Time of study: 2007–2009 | Intervention: 9-month program involving environmental and educational components (e.g., provision of educational material, food tasting stand). Main finding: On average, the coverage of educational activities and materials was 63.5%. FV consumption increased by 38% in employees. | Theory: Not reported. Recruitment: None reported. | Participation method: Focus groups to inform intervention design. Data collection techniques: Focus groups, intervention development considering stakeholder preferences/needs. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess background knowledge and evidence, assess user needs to inform intervention focus, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Collaborative Standard of Reporting score: 2 |

| Hemmingsson et al. (2012) [40]: To evaluate weight loss and the dropout rate after a 1-year commercial weight loss program. | Study design: Observational cohort study. Participants: Enrolled customers in a weight loss program with a mean age of 48 ± 12 years (range: 18–81 years) Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: Sweden. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: 1-year structured weight loss support program with 1-h group sessions. Very low calorie diet, low calorie diet, or restricted normal-food diets offered. Main finding: After 1 y, mean (±SD) weight changes were −11.4 ± 9.1 kg with the VLCD (18% dropout), −6.8 ± 6.4 kg with the LCD, and −5.1 ± 5.9 kg with the restricted normal-food diet. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Not specified. | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention to participants’ health goals, food preferences, and nutritional requirements. Data collection techniques: Interview/discussion between participant and health coaches. Decision was based on baseline BMI, desired weight loss, and personal preference.Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 3 |

| Hernandez et al. (2014) [41]: To evaluate the effects of a diet high in total carbohydrate (higher-complex, lower glycaemic index [GI]) and minimal fat on control of maternal glycemia and postprandial lipids. Related works: Hernandez et al. (2016) [42] | Study design: Quantitative (Randomised crossover trial) Participants: Women with diet-controlled gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), n = 16, 28.4 ± 1.0 years. Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: University Hospital, Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institute; Colorado, USA. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Higher-complex carbohydrate (HCC) and lower-fat (LF) ‘Choosing Healthy Options In Carbohydrate Energy’ (CHOICE) diet. Main finding: A diet high in complex carbohydrates and limited fat was effective in controlling maternal glycemia to within current recommended ranges. | Theory: Not reported Recruitment: Not reported | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention to participants’ health goals, food preferences, and nutritional requirements. Data collection techniques: Food frequency questionnaire completed to establish calorie requirements for individual participants. Data analysis techniques: Descriptive. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 2 |

| Hiel et al. (2019) [43]: To evaluate the impact of daily consumption of inulin-rich vegetables on gut microbiota, gastrointestinal symptoms, and food-related behaviour in healthy individuals. | Study design: Quantitative—single group-design trial Participants: Healthy adults (n = 25) aged 21.84 ± 0.39 years Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: Université Catholique de Louvai, Belgium. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Dietary intervention including inulin-type fructans (ITFs)-rich vegetables to reach a minimum intake of at least 9 g ITF/d in healthy volunteers Main finding: Higher consumption of ITF-rich vegetables associated with increase in well-tolerated dietary fibre. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Not reported. | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention to participants’ previous intake/acceptability of vegetables. Data collection techniques: Food diaries, fasting breath samples, visual analogue scales, stool samples. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 0 |

| Jacobsson et al. (2012) [44]: To examine the impact of active patient education on gastrointestinal symptoms in women with a gluten-free diet. | Study design: Quantitative (Randomised controlled trial) Participants: Women with coeliac disease (n = 106), mean age = 53 years, range = 23–80 years Other stakeholders: PBL expert supervised instructors. Setting: Hospitals, Southeast Sweden. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: 10-session educational program to support and encourage self-identification of lifestyle changes to reduce gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and explore new knowledge. Main finding: “Celiac School” participation was associated with significant improvements. | Theory: Problem-based learning Recruitment: Not reported | Participation method: Problem-based learning. Data collection techniques: Weekly meetings in groups of 7–9 persons conducted by a tutor familiar with PBL, self-report questionnaires. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, develop intervention content. | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 4 |

| Kim et al. (2013) [45]: To translate and validate a culturally modified DASH for Koreans (K-DASH) and gather preliminary evidence of efficacy. | Study design: Mixed methods with pre–post intervention evaluation design. Participants: Korean Americans (n = 30), mean age = 55.3 (6.8) years Other stakeholders: Clinicians; community health workers were involved in group education sessions. Setting: Centrally located community-based organisation, The Korean Resource Centre, in the Baltimore-Washington metropolitan area, USA. Time of study: 2011 | Intervention: 10-week culturally modified K-DASH intervention consisting of two structured in-class education sessions with interactive group activities, 3 individually tailored nutrition consultations with a bilingual nurse/dietician team, and 1 follow-up telephone call. Main finding: Both systolic blood pressure and diastolic were significantly decreased at postintervention evaluation. A culturally relevant and efficacious dietary intervention was produced. | Theory: Community-based participatory research Recruitment: Advertisements, personal networks, referrals from community physician networks. | Participation method: Community-based participatory action research. Data collection techniques: Needs analysis, review of evidence, focus groups, pre–post intervention evaluation. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 3 |

| Madjd et al. (2016) [46]: To compare the effect of high energy intake at lunch with that at dinner on weight loss and cardiometabolic risk factors in women during a weight loss program. | Study design: Quantitative (Randomised clinical trial) Participants: Overweight or obese women (n = 80), 18–45 years. Other stakeholders: None reported Setting: NovinDiet weight loss clinic, Iran. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Hypoenergetic diet: high-carbohydrate, low-saturated fat diet, with ≥400 g fruit and vegetables to achieve fibre intake recommendation of 25 g/day]. Main meal consumed either at lunch (LM) or dinner (DM). Main finding/outcome: Compared with the DM group, LMgroup had greater reductions in weight and BMI. | Theory: Stages of change model Recruitment: Not specified. | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention to participants’ food diaries and preferences. Data collection techniques: Anthropometric measurements, blood samplesData analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 2 |

| Mosher et al. (2013) [47]: To examine whether changes in self-efficacy explain the effects of a mailed print intervention on long-term dietary habits among breast and prostate cancer survivors. | Study design: Quantitative (Randomised trial) Participants: Diagnosed with early-stage breast or prostate cancer within the prior nine months (n = 543), mean age = 57.2 (10.7) years Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: Community-based; North America. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: FRESH START 10-month mailed print interventions focused to improve diet and PA; based on Social Cognitive Theory. Main finding: Change in self-efficacy for fat restriction partially explained effect on fat intake; change in self-efficacy for F&V consumption partially explained change in daily F&V intake. | Theory: Social Cognitive Theory; Observational learning Recruitment: Cancer registries of participating medical centres, large oncology practices, or self-referral. | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention content to participants’ current diet and physical activity behaviours and other factors. Data collection techniques: Diet History Questionnaire, 7-day Physical activity Recall, self-efficacy. Data analysis techniques: Descriptive. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 6 |

| Nybacka et al. (2017) [48]: To examine the effects of diet and exercise interventions on metabolic profile and cardiovascular risk factors women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). | Study design: Quantitative (Randomised controlled trial) Participants: Women with PCOS (n = 57) 18–40 years Other stakeholders: None reported. Setting: Women’s Health Research Unit, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: Diet, exercise, or diet + exercise 16 week program. Diets individually designed with dietitian, seeking 600 kcal/day reduction in calorie consumption. Main finding/outcome: BMI, waist circumference and total cholesterol significantly reduced in diet and diet + exercise groups. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Not reported. | Participation method: Tailoring of intervention to suit participants’ individual nutritional requirements and food preferences. Data collection techniques: Self-reported food intake, pedometer, fasting blood test, DEXA scan. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 2 |

| Rudel et al. (2011) [49]: To evaluate the contribution of food packaging to exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA) and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) chemicals used in food packaging. | Study design: Quantitative (Quasi-experimental pre–post design) Participants: Family members with exposure to BPAs (e.g., consumed canned foods): n = 20. Median age of the 10 adults was 40.5 years, median age of the 10 children was 7 years. Other stakeholders: Caterer. Setting: Community-based, San Francisco Bay Area, USA. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: A three-day special diet of fresh foods (no canned foods) prepared and packaged almost exclusively without contact with plastic. Main finding/outcome: The fresh foods intervention reduced geometric mean concentrations of BPA by 66% and DEHP metabolites by 53–56%. | Theory: Not reported Recruitment: Letters sent via listservs. | Participation method: Stakeholder input into menu design. Data collection techniques: Urine samples, daily phone calls with research staff, food questionnaires. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 3 |

| Shahar et al. (2012) [50]: To develop nutrition education materials to promote healthy aging and reducing risk of chronic diseases in older adults living in a rural area. | Study design: Qualitative (Participatory Action Research) Participants: Older adults (≥60 years old; n = 33); Health professionals, e.g., rural clinic staff, physicians, medical assistants, nurses (n = 14) with a mean age of 30.9 ± 8.3 years. Other stakeholders: A professional artist; dietitians, nutritionists, public health physicians and anthropologist. Setting: Health clinics in Klang Valley, Malaysia. Time of study: Not reported. | Intervention: A nutrition education package (booklet, flipchart, and placemats). Main finding/outcome: A total of 42.4% of the older adults expressed that the sentences in the flipchart needed to be simplified and medical terms explained. Terminology, illustrations, and nutrition recommendations were barriers to understanding of educational materials. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Not specified | Participation method: Three stage-approach: Needs assessment, intervention development, evaluation (prototype testing). Data collection techniques: self-administered questionnaire. Data analysis techniques: Descriptive analysis. | Prototype testing | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 6 |

| Uddin et al. (2017) [51]: To develop and test a mobile phone-based system to improve health, population and nutrition services in rural Bangladesh and evaluate its impact on service delivery. | Study design: Quantitative (Quasi-experimental pre–post design). Participants: Target population: currently married women of reproductive age. Other stakeholders: Service-delivery personnel, health, and planning officers. Setting: two administrative divisions of Bangladesh. Time of study: Not applicable. | Intervention: Mobile phone-basedsystem to improve health, population, and nutrition services in rural Bangladesh. Main finding/outcome: Establishment of a research protocol. | Theory: None reported. Recruitment: Routine community visits of health and family planning workers. | Participation method: Intervention designed with input (feedback) from stakeholders. Data collection techniques: Surveys. Data analysis techniques: Not specified. | Assess user needs to inform intervention focus, pilot/real-world testing. | Participatory Action Research standard: Consultative Standard of Reporting score: 4 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tay, B.S.J.; Cox, D.N.; Brinkworth, G.D.; Davis, A.; Edney, S.M.; Gwilt, I.; Ryan, J.C. Co-Design Practices in Diet and Nutrition Research: An Integrative Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103593

Tay BSJ, Cox DN, Brinkworth GD, Davis A, Edney SM, Gwilt I, Ryan JC. Co-Design Practices in Diet and Nutrition Research: An Integrative Review. Nutrients. 2021; 13(10):3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103593

Chicago/Turabian StyleTay, Brenda S. J., David N. Cox, Grant D. Brinkworth, Aaron Davis, Sarah M. Edney, Ian Gwilt, and Jillian C. Ryan. 2021. "Co-Design Practices in Diet and Nutrition Research: An Integrative Review" Nutrients 13, no. 10: 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103593

APA StyleTay, B. S. J., Cox, D. N., Brinkworth, G. D., Davis, A., Edney, S. M., Gwilt, I., & Ryan, J. C. (2021). Co-Design Practices in Diet and Nutrition Research: An Integrative Review. Nutrients, 13(10), 3593. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103593