Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle through Mindfulness in University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mindfulness-Based Meditation

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

- Discussion and feedback on the mindfulness meditation exercises practiced during the previous week.

- Ten-minute guided-mindful body-scan.

- Presentation of the various metaphors and exercises corresponding to each session.

- Practice of mindful breathing for 30 min.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Measures

2.5. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Navarro-Prado, S.; González-Jiménez, E.; Perona, J.S.; Montero-Alonso, M.A.; López-Bueno, M.; Schmidt-RioValle, J. Need of improvement of diet and life habits among university student regardless of religion professed. Appetite 2017, 114, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.; Barbosa, M.L.; Rodrigues, B.; Da Silva, C.C.N.; Moura, A.A. Association between the Degree of Processing of Consumed Foods and Sleep Quality in Adolescents. Nutrients 2020, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardet, A. Characterization of the Degree of Food Processing in Relation with Its Health Potential and Effects. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2018, 85, 79–129. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, M.; Seo, Y.S.; Park, E.; Chang, Y.P. Association between substance use and insufficient sleep in US high school students. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, A.E.; Hall, K.E.; Vigil, D.I.; Rosenthal, A.; Azofeifa, A.; Van Dyke, M. Results from the Colorado Cannabis Users Survey on Health (CUSH), 2016. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buu, A.; Hu, Y.H.; Wong, S.W.; Lin, H.C. Internalizing and Externalizing Problems as Risk Factors for Initiation and Progression of E-cigarette and Combustible Cigarette Use in the US Youth Population. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero-Jurado, M.D.M.; Gázquez-Linares, J.J.; Martos-Martínez, Á.; Mercader-Rubio, I.; Saracostti, M. Individual variables involved in perceived pressure for adolescent drinking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, M.D.; Brown, S. Is Mobile Addiction a Unique Addiction: Findings from an International Sample of University Students. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litsfeldt, S.; Ward, T.M.; Hagell, P.; Garmy, P. Association between sleep duration, obesity, and school failure among adolescents. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. The Role of Active Coping in the Relationship Between Learning Burnout and Sleep Quality Among College Students in China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumfield, M.L.; Bei, B.; Zimberg, I.Z.; Cain, S.W. Dietary disinhibition mediates the relationship between poor sleep quality and body weight. Appetite 2018, 120, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gázquez Linares, J.J.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.D.C.; Molero Jurado, M.D.M.; Oropesa-Ruiz, N.F.; Márquez, S.; del Mar, M.; Saracostti, M. Sleep Quality and the Mediating Role of Stress Management on Eating by Nursing Personnel. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, A. Sport and Eating Disorders—Understanding and Managing the Risks. Asian J. Sports Med. 2010, 1, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, V.J.; Puig-Perez, S.; Becoña, E. Efficacy of the “Sé tú Mismo”(Be Yourself) Program in Prevention of Cannabis Use in Adolescents. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-González, L.; Amutio, A.; Oriol, X.; Bisquerra, R. Hábitos relacionados con la relajación y la atención plena (mindfulness) en estudiantes de secundaria: Influencia en el clima de aula y el rendimiento académico. Revista Psicodidáctica 2016, 21, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeller, J.L.; Wolever, R. Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training: Treatment of overeating and obesity. In Mindfulness-Based Treatment Approaches, 2nd ed.; Baer, R.A., Ed.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shead, N.W.; Champod, A.S.; MacDonald, A. Effect of a Brief Meditation Intervention on Gambling Cravings and Rates of Delay Discounting. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.; Singh, S.; Sibinga, E.M.; Gould, N.F.; Rowland-Seymour, A.; Sharma, R.; Berger, Z.; Sleicher, D.; Maron, D.D.; Shihab, H.M.; et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C. Third-Generation Mindfulness & the Universe of Relaxation; (Professional Version); Kendall Hunt: Dubuque, IA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan, M.M. Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sayrs, J.H.R.; Linehan, M.M. DBT Teams: Development and Practice; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Telch, C.F.; Agras, W.S.; Linehan, M.M. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life; Hyperion: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Segal, Z.V.; Williams, J.M.G.; Teasdale, J.D. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Oraki, M.; Ghorbani, M. The effectiveness of mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) on perceived stress and body mass index in overweight women. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2019, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, C.; Ferradas, M.d.M.; Regueiro, B.; Rodríguez, S.; Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C. Coping Strategies and Self-Efficacy in University Students: A Person-Centered Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, W.B.; Haynes, P.L.; Fridel, K.W.; Bootzin, R.R. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy improves polysomnographic and subjective sleep profiles in antidepressant users with sleep complaints. Psychother. Psychosom. 2012, 81, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Feinholdt, A.; Nübold, A. A low-dose mindfulness intervention and recovery from work: Effects on psychological detachment, sleep quality, and sleep duration. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 464–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.S.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R. The Neuroscience of Mindfulness: How Mindfulness Alters the Brain and Facilitates Emotion Regulation. Mindfulness 2017, 8, 1471–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C. Meditación Fluir para Serenar el Cuerpo y la Mente; Bubok: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, C.; Amutio, A.; López-González, L.; Oriol, X.; Martínez-Taboada, C. Effect of a mindfulness training program on the impulsivity and aggression levels of adolescents with behavioral problems in the classroom. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, A.; Franco, C.; Sánchez, L.C.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez-Linares, J.J.; Van Gordon, W.; Molero-Jurado, M.M. Effects of Mindfulness training on sleep problems in patients with fybromialgia. Front. Psychol. (Sect. Clin. Health Psychol.) 2018, 9, 1365. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, C.; Amutio, A.; Mañas, I.; Sánchez, L.C.; Mateos, E. Improving psychosocial functioning in mastectomized women through a mindfulness-based program: Flow Meditation. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2020, 27, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain and Illness; Delacorte: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Carrascoso, F.J. Terapia de aceptación y compromiso: Características, técnicas clínicas básicas y hallazgos empíricos. Psicol. Conduct. 2006, 14, 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Stroshal, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, K.G.; Luciano, M.C. Terapia de Aceptación y Compromiso. Un tratamiento Conductual Orientado a los Valores; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Deshimaru, T. La Práctica del Zen; RBA: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, W. La Vippasana. El Arte de la Meditación; Luz de Oriente: Madrid, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Frankl, V.E. The will to Meaning: Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy; Penguin: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, S.J. Applied Logotherapy: Viktor Frankl’s Philosophical Psychology; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Esalati, P.; Arab, A.; Mehdinezhad, V. Effectiveness of Frankl’s Logotherapy on Health (Decreasing Addiction Potential and Increasing Psychological Well-being) of Students with Depression. Iran. J. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 7, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, A.; Franco, C.; Mercader, I.; Pérez-Fuentes, M.C.; Gázquez, J.J. Mindfulness training for reducing anger, anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia patients. Front. Psychol. (Psychol. Clin. Settings) 2015, 5, 1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Sumich, A.; Sundin, E.C.; Griffiths, M.D. Meditation awareness training (MAT) for psychological well-being in a sub-clinical sample of university students: A controlled pilot study. Mindfulness 2014, 5, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, M.; Lobato, S.; Batista, M.; Aspano, M.I.; Jiménez, R. Validación del cuestionario de estilo de vida saludable (EVS) en una población española. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2018, 13, 23–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Carracedo, D.S.; Saldaña, C. Evaluación de los hábitos alimentarios en adolescentes con diferentes índices de masa corporal. Psicothema 1998, 10, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserstein, R.L.; Lazar, N.A. The ASA’s statement on p-values: Context, process, and purpose. Am. Stat. 2016, 70, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gordon, W.; Shonin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Towards a second generation of mindfulness-based interventions. Aust. N. Zealand J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requero, B.; Briñol, P.; Moreno, L.; Paredes, B.; Gandarillas, B. Promoting healthy eating by enhancing the correspondence between attitudes and behavioral intentions. Psicothema 2020, 32, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kubik, M.Y.; Fulkerson, J.A. Missed Work among Caregivers of Children with a High Body Mass Index: Child, Parent, and Household Characteristics. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulou, I.; Kotopoulea-Nikolaidi, M.; Daskou, S.; Martyn, K.; Patel, A. Mindfulness in eating is inversely related to binge eating and mood disturbances in university students in health-related disciplines. Nutrients 2020, 12, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdier, L.; Orri, M.; Carre, A.; Gearhardt, A.N.; Romo, L.; Dantzer, C.; Berthoz, S. Are emotionally driven and addictive-like eating behaviors the missing links between psychological distress and greater body weight? Appetite 2018, 120, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katterman, S.N.; Kleinman, B.M.; Hood, M.M.; Nackers, L.M.; Corsica, J.A. Mindfulness meditation as an intervention for binge eating, emotional eating, and weight loss: A systematic review. Eat. Behav. 2014, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.B.; Daiss, S.; Krietsch, K. Associations among self-compassion, mindful eating, eating disorder symptomatology, and body mass index in college students. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2015, 1, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanen, J.W.; Nazir, R.; Sedky, K.; Pradhan, B.K. The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on sleep disturbance: A meta-analysis. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amutio, A.; Franco, C.; Gázquez, J.J.; Mañas, I. Aprendizaje y práctica de la conciencia plena en estudiantes de bachillerato para potenciar la relajación y la autoeficacia en el rendimiento escolar. Univ. Psychol. 2015, 14, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, P.; Fischer, D.; Wamsler, C. Mindfulness, Education, and the Sustainable Development Goals. In Quality Education, Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, L., Brandli, P., Özuyar, G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; Volume 10, pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-3-319-69902-8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Kee, Y.H.; Lam, L.S. Effect of brief mindfulness induction on universityathletes’ sleep quality following night training. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session 1: Introduction to mindfulness and flow meditation through different Zen metaphors and teachings. Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. |

| Session 2: Sense meditation (face). Talk on learning to observe all mental events and let them be and flow; learning the difference between reacting and acting with awareness. Practice of flow meditation (e.g., mindful breathing). Group discussion. |

| Session 3: Sense meditation (abdomen and chest). Talk on learning how to tolerate negative feelings and thoughts during the practice of mindfulness and in daily life. Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. |

| Session 4: Sense meditation (back). Talk on how our minds tend to be in the past or future, and learning how to live in the present moment with awareness. Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. |

| Session 5: Sense meditation (arms). Talk on the impermanency of everything. Exercise of counting thoughts and see them constantly flowing in order to be aware of their transitory and impermanency. Additionally, learning how to break the association between thinking, feeling, and acting. Talk on the concept of equanimity and emphasizing that the goal is not learning how to control and dominate our minds, but to learn how not to be overwhelmed and controlled by them. Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. |

| Session 6: Sense meditation/Vipassana meditation (all body). Talk on the role of our attitudes in the evaluation of the events and circumstances of our life and how this evaluation determines our life satisfaction and well-being. Learning acceptance of unpleasant states through different exercises. Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. |

| Session 7: Sense meditation/Vipassana meditation (all body). Learning how to observe and detect negative mental patterns that prevent us from being happy and satisfied with our lives (e.g., “musts”, “oughts”). Practice of flow meditation. Group discussion. The course ends by encouraging participants to practice mindfulness daily. |

| Variables | Experimental | Control | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-Test | Pre-test | Post-Test | |||||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | Z/F | p | r/ ɳ2p | M | DS | M | SD | Z/F | p | r/ɳ2p | |

| Tobacco use | 6.50 | 2.98 | 5.54 | 2.26 | Z = −3.14 | ** | 0.439 | 6.36 | 3.22 | 6.64 | 3.39 | Z = −1.94 | 0.271 | |

| Cannabis consumption | 5.54 | 2.73 | 4.92 | 2.07 | Z = −3.20 | ** | 0.448 | 5.08 | 2.73 | 5.32 | 3.06 | Z = −2.45 | * | 0.343 |

| Alcohol consumption | 7.38 | 3.03 | 6.19 | 2.11 | Z = −3.66 | *** | 0.512 | 6.60 | 2.59 | 7.00 | 2.81 | Z = −1.31 | 0.183 | |

| Meal times | 6.96 | 2.30 | 7.92 | 2.27 | F = −1.28 | 0.073 | 6.80 | 2.10 | 7.32 | 1.99 | F = 1.09 | 0.02 | ||

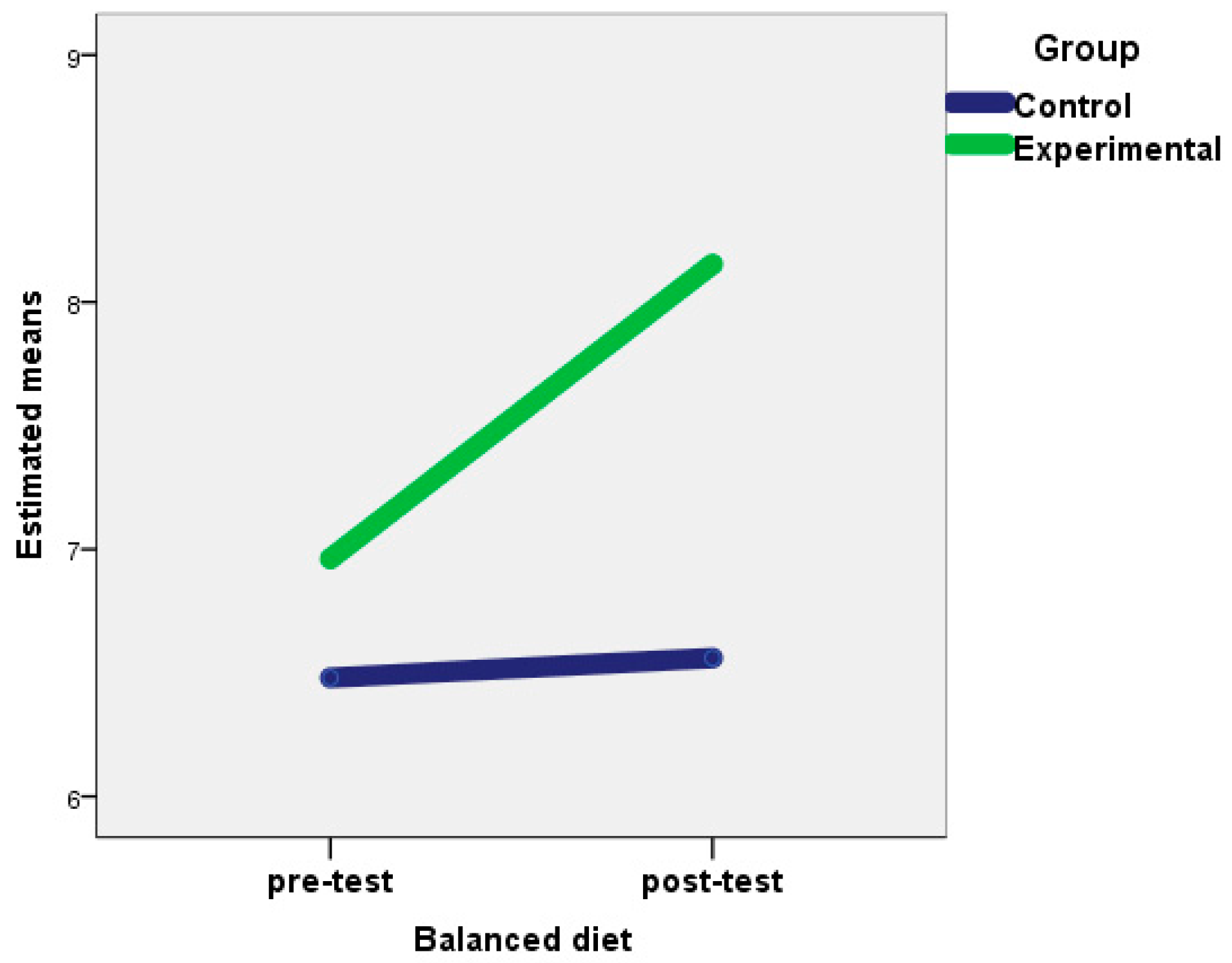

| Balanced diet | 6.96 | 1.48 | 8.15 | 1.40 | F = 7.74 | ** | 0.14 | 6.48 | 1.38 | 6.56 | 1.55 | F = 0.34 | 0.001 | |

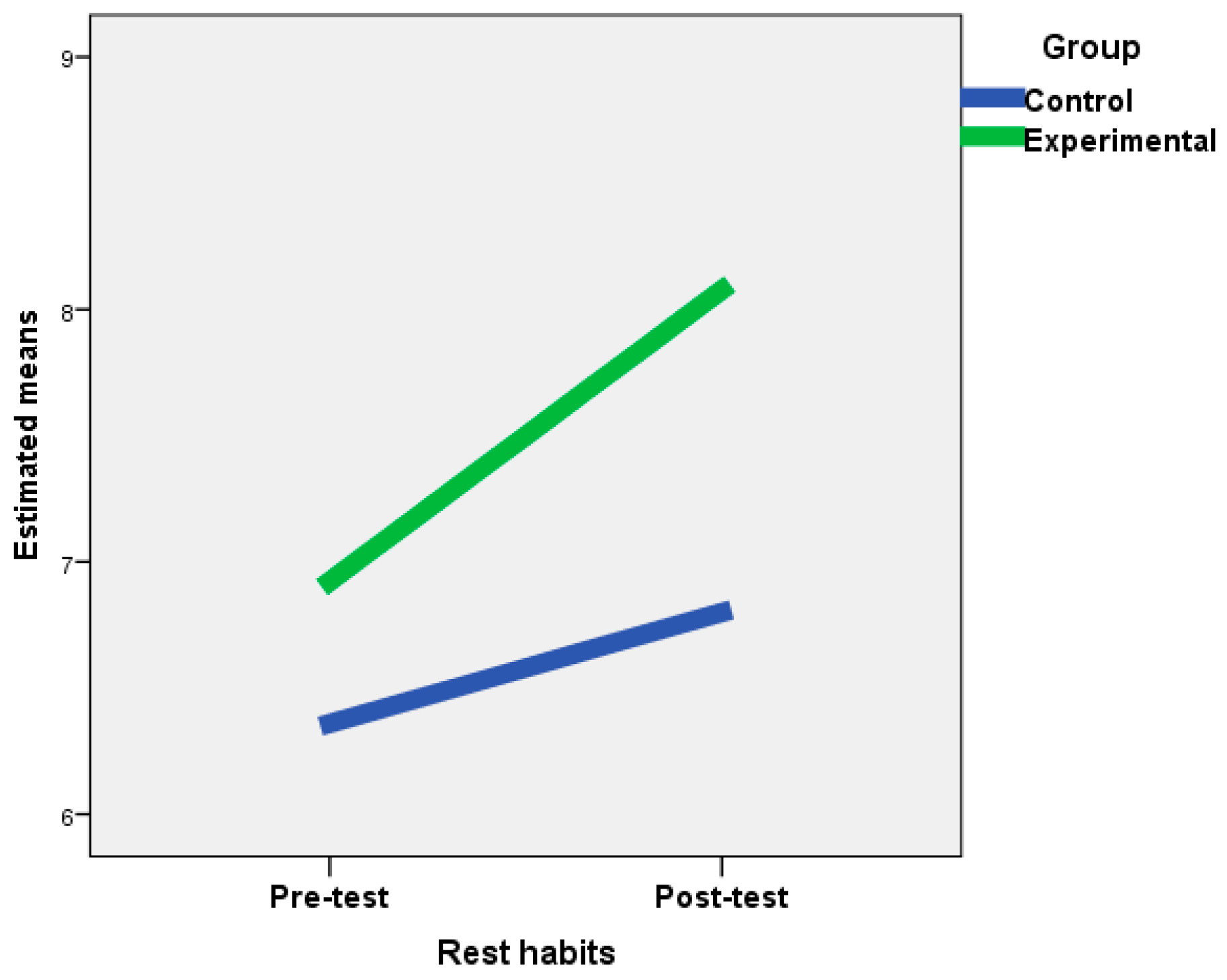

| Rest habits | 6.92 | 1.62 | 8.08 | 1.32 | F = 10.05 | ** | 0.17 | 6.36 | 1.57 | 6.80 | 1.29 | F = 1.39 | 0.028 | |

| Externality | 31.73 | 7.15 | 27.92 | 5.78 | Z = −4.03 | *** | 0.564 | 31.56 | 7.73 | 31.32 | Z = −0.259 | 8.20 | 0.362 | |

| Decrease in food consumption due to NES | 21.85 | 5.45 | 18.35 | 3.03 | Z = −3.93 | *** | 0.550 | 20.92 | 5.44 | 21.92 | 5.09 | Z = −2.85 | ** | 0.399 |

| Increase in food consumption due to NES | 21.81 | 6.19 | 17.62 | 3.61 | Z = −4.12 | *** | 0.577 | 22.68 | 5.47 | 23.36 | 5.13 | Z = −2.70 | ** | 0.378 |

| Food consumption amount | 16.27 | 4.30 | 12.81 | 2.51 | Z = −4.21 | *** | 0.590 | 16.52 | 4.29 | 17.32 | 4.17 | Z = −3.08 | * | 0.431 |

| Snacking between meals | 3.31 | 1.12 | 2.46 | 0.51 | Z = −3.17 | ** | 0.443 | 3.20 | 1.04 | 3.36 | 0.90 | Z = −2.00 | * | 0.280 |

| Consumption of light products | 3.23 | 1.21 | 3.38 | 1.10 | F = 3.21 | 0.062 | 3.36 | 0.99 | 3.16 | 0.85 | F = 5.22 | * | 0.096 | |

| Intake rate | 7.08 | 1.89 | 6.08 | 1.06 | Z = −2.96 | ** | 0.416 | 6.92 | 1.89 | 7.36 | 1.65 | Z = −2.31 | * | 0.323 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soriano-Ayala, E.; Amutio, A.; Franco, C.; Mañas, I. Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle through Mindfulness in University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082450

Soriano-Ayala E, Amutio A, Franco C, Mañas I. Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle through Mindfulness in University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082450

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoriano-Ayala, Encarnación, Alberto Amutio, Clemente Franco, and Israel Mañas. 2020. "Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle through Mindfulness in University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082450

APA StyleSoriano-Ayala, E., Amutio, A., Franco, C., & Mañas, I. (2020). Promoting a Healthy Lifestyle through Mindfulness in University Students: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients, 12(8), 2450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082450