The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy—OzHarvest’s NEST Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The NEST Program

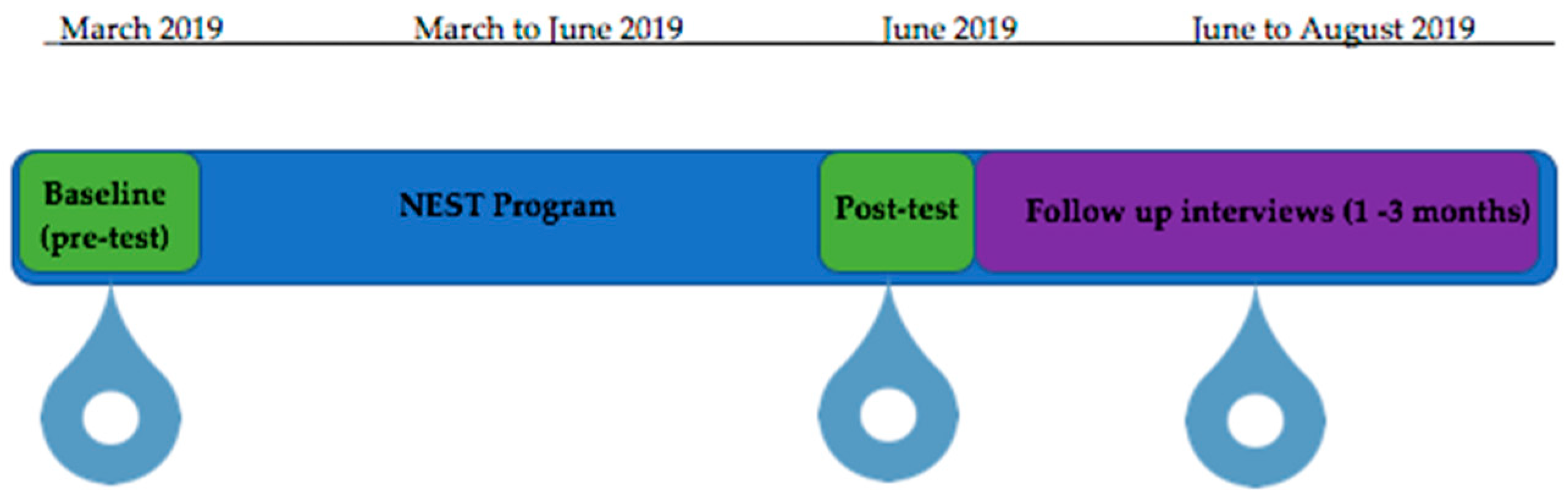

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. Pre-Post Surveys

Food Security

Food Literacy

Dietary Intake

2.2.2. Interviews

2.3. Analysis

2.3.1. Pre-Post Surveys

2.3.2. Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Post NEST Survey Results

3.1.1. Demographics

3.1.2. Food Security

3.1.3. Cooking Confidence, Food Behaviours, and Nutrition Knowledge

3.1.4. Dietary Intake

3.2. Interview Results

3.2.1. NEST Improves Food Literacy and Food Utilisation

Cooking Confidence

Food Preparation and Cooking Methods

From the fifteen months I had been in <rehabilitation> we used to have four or five days a week of fried foods… Mainly from awareness, mainly from affordability… So, what the NEST program was teaching us… we have been incorporating that into our weekly menus… a healthier way of cooking with healthier oils… to do chips steamed or oven… we don’t need to put everything in the deep fryer, which is what we were doing.

Food Selection and Eating Behaviours

Stretching Food Budgets and Saving Money

When I became unemployed it was like we can’t have those easy quick meals because they’re not cheap. So, I had to re-learn myself how to cook meals again and make them stretch… I just got so caught up in easy buy stuff, and like just for the convenience of it all. Because we went from having two fairly good wages to one wage that barely covered anything, we really had to learn how to–just the basics again. I know it sounds so silly, but it’s true…

3.2.2. Enablers for Food Security

Receiving and Providing Support to Family or Friends

Provision of Charitable Food

3.2.3. Barriers to Food Security

Lack of Economic Access to Food

Unfortunately, due to the cost of living and expenses, making food and getting food is quite hard… you need a roof over your head and you need to be able to pay bills and stuff, so try and pay them off... Then food generally comes last. It just means lack of food a lot of the time… there’s no point in me saying, ‘Yes, I’ll cook three meals a day and I’ll make sure to include every type of food.’ Because of course, that would straight away be a fail because it’s not accessible.

Pre-Existing Health Issues

Provision of Charitable Food

we’re given a bag of food and sometimes it’s quite simply a loaf of bread, a little bag of cereal, and some muesli bars and maybe one packet of pasta. Which means it doesn’t go far… as grateful as we are for the amount of food we get, it’s not possible to make certain recipes out of it. And quite simply put, if there’s no ability to cook… it’s just going to actually make you feel more upset.

4. Discussion

4.1. The Role of NEST on Food Security and Food Literacy

4.2. Barriers and Enablers to Food Security

4.3. Implications

4.3.1. Implications for Research

4.3.2. Implications for Policy

4.3.3. Implications for Practice

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO); International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD); World Food Program (WFP); World Health Organization (WHO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018: Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, R.; Barbour, L.; Godrich, S. A rights-based approach to food insecurity in Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2020, 00, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, R.; Giskes, K.; Turrell, G.; Gallegos, D. Food insecurity among adults residing in disadvantaged urban areas: Potential health and dietary consequences. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foodbank Australia; McCrindle Research. Foodbank Hunger Report 2018; Foodbank Australia: North Ryde, Austrilia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agricultural Organisation. An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security; EC-FAO Food Security Programme: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.M.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Examining the association between food literacy and food insecurity. Nutrients 2019, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallegos, D. Food literacy. In Routledge Studies in Food, Society and Environment; Vidgen, H., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Gallegos, D.; Vidgen, H. Effectiveness of Australian cooking skill interventions. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 973–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, R.L.; Maulding, M.K.; Abbott, A.R.; Craig, B.A.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. SNAP-Ed (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education) Increases long-term food security among Indiana households with children in a randomized controlled study. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Mason, A.C.; Abbott, A.R.; McCabe, G.P.; Boushey, C.J. The effect of Food Stamp Nutrition Education on the food insecurity of low-income women participants. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2009, 41, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.L.; Reardon, R.; McDonald, M.; Vargas-Garcia, E.J. Community interventions to improve cooking skills and their effects on confidence and eating behaviour. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2016, 5, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flynn, M.M.; Reinert, S.; Schiff, A.R. A Six-Week Cooking program of plant-based recipes improves food security, body weight, and food purchases for food pantry clients. J. Hunger Env. Nutr. 2013, 8, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, J.A.; Morgan, R.E.; Wong, K.; Wilkin, M.K.; Blitstein, J.L. Cooking matters for adults improves food resource management skills and self-confidence among low-income participants. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2017, 49, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, R.L.; Dunne, J.; Maulding, M.K.; Wang, Q.; Savaiano, D.A.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. Exploring the association of urban or rural county status and environmental, nutrition- and lifestyle-related resources with the efficacy of SNAP-Ed (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education) to improve food security. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, L.; Chaidez, V.; Algert, S.; Horowitz, M.; Martin, A.; Mendoza, C.; Neelon, M.; Ginsburg, D.C. Food resource management education with SNAP participation improves food security. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 374–378.e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, L.R.; Ho, M.Y.L.; Davidson, Z.E.; Palermo, C.E. Challenges and opportunities for measuring the impact of a nutrition programme amongst young people at risk of food insecurity: A pilot study. Nutr. Bull. 2016, 41, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollahite, J.S.; Pijai, E.I.; Scott-Pierce, M.; Parker, C.; Trochim, W. A randomized controlled trial of a community-based nutrition education program for low-income parents. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2014, 46, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, S.A. Understanding food and nutrition-related behaviours: Putting together the pieces of the puzzle. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 69, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines; National Health and Medical Research Council: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychol. Health 1998, 13, 623–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Auld, G.; Ammerman, A.; Lohse, B.; Serrano, E.; Wardlaw, M.K. Identification of a framework for best practices in nutrition education for low-income audiences. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health C 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, V. Research methods: Triangulation. Evid. Based Libr. Inf. Pract. 2014, 9, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flego, A.; Herbert, J.; Gibbs, L.; Swinburn, B.; Keating, C.; Waters, E.; Moodie, M. Methods for the evaluation of the Jamie Oliver Ministry of Food program, Australia. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bickel, G.; Nord, M.; Price, C.; Hamilton, W.; Cook, J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security. Revised: 2000; United States Department of Agriculture: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Devine, C.M.; Farrell, T.J.; Hartman, R. Sisters in health: Experiential program emphasizing social interaction increases fruit and vegetable intake among low-income adults. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, K.; Wrieden, W.; Anderson, A. Validity and reliability of a short questionnaire for assessing the impact of cooking skills interventions. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A.; Le, H.; Andrianopoulos, N.; Inglis, V.; McNeilly, B.; Lichomets, I.; Granados, A.; Crawford, D. ShopSmart 4 health–protocol of a skills-based randomised controlled trial promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wrieden, W.L.; Anderson, A.S.; Longbottom, P.J.; Valentine, K.; Stead, M.; Caraher, M.; Lang, T.; Gray, B.; Dowler, E. The impact of a community-based food skills intervention on cooking confidence, food preparation methods and dietary choices–an exploratory trial. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pettigrew, S.; Moore, S.; Pratt, I.S.; Jongenelis, M. Evaluation outcomes of a long-running adult nutrition education programme. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLennan, W.; Podger, A. National Nutrition Survey: Selected Highlights 1995; Australian Bureau of Statistics: Canberra, Australia, 1997.

- Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A.; Le, H.N.; Abbott, G.; Stephens, L.D.; Crawford, D.A. ShopSmart 4 Health: Results of a randomized controlled trial of a behavioral intervention promoting fruit and vegetable consumption among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4364.0.55.001-National Health Survey: First Results; 2017–2018; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Booth, S. Researching health and homelessness: Methodological challenges for researchers working with a vulnerable, hard to reach, transient population. Aust. J. Prim. Health 1999, 5, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiklejohn, S.J.; Barbour, L.; Palermo, C.E. An impact evaluation of the FoodMate programme: Perspectives of homeless young people and staff. Health Educ. J. 2017, 76, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.E.; Hanrahan, K.J. Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qual. Res. 2004, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, S. Eating rough: Food sources and acquisition practices of homeless young people in Adelaide, South Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wicks, R.; Trevena, L.J.; Quine, S. Experiences of food insecurity among urban soup kitchen consumers: Insights for improving nutrition and well-being. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2006, 106, 921–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, G.F.; Audrey, S.; Barker, M.; Bond, L.; Bonell, C.; Hardeman, W.; Moore, L.; O’Cathain, A.; Tinati, T.; Wight, D. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. Brit. Med. J. 2015, 350, h1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ball, K.; MacNaughton, S.; Lindberg, R. NEST Program Evaluation Framework; Institute for Physical Activitiy and Nutrition (IPAN): Melbourne, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- STATA. Statistical Software Release 15.0; StatCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Auld, G.; Baker, S.; Conway, L.; Dollahite, J.; Lambea, M.C.; McGirr, K. Outcome effectiveness of the widely adopted EFNEP curriculum eating smart∙ being active. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustad, C.; Smith, C. Nutrition knowledge and associated behavior changes in a holistic, short-term nutrition education intervention with low-income women. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013, 45, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustad, C.; Smith, C. A short-term intervention improves nutrition attitudes in low-income women through nutrition education relating to financial savvy. J. Hunger Env. Nutr. 2012, 7, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, P.; Bedford, M. New Minimum Income for Healthy Living Budget Standards for Low-Paid and Unemployed Australians; Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW Sydney: Sydney, Autrilia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, R.; Abrami, A.; Rapoport, R.; Sriphanlop, P.; Sacks, R.; Johns, M. A mixed-methods evaluation of a SNAP-Ed farmers’ market-based nutrition education program. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Eakin, J.M. Charitable food assistance as symbolic gesture: An ethnographic study of food banks in Ontario. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppendieck, J. Sweet Charity? Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Riches, G. First World Hunger: Food Security and Welfare Politics; Palgrave Macmillan: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vlaholias-West, E.; Thompson, K.; Chiveralls, K.; Dawson, D. The ethics of food charity. In Encyclopedia of Food and Agricultural Ethics; Kaplan, D.M., Ed.; Springer: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, A.; Backholer, K.; Magliano, D.; Peeters, A. The effect of obesity prevention interventions according to socioeconomic position: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2014, 15, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, G.; Ball, K.; Arbuckle, J.; Crawford, D. Dietary patterns of Australian adults and their association with socioeconomic status: Results from the 1995 National Nutrition Survey. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kleve, S.; Gallegos, D.; Ashby, S.; Palermo, C.; McKechnie, R. Preliminary validation and piloting of a comprehensive measure of household food security in Australia. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jones, A.D.; Ngure, F.M.; Pelto, G.; Young, S.L. What are we assessing when we measure food security? A compendium and review of current metrics. Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pollard, C.M.; Booth, S.; Jancey, J.; Mackintosh, B.; Pulker, C.E.; Wright, J.L.; Begley, A.; Imtiaz, S.; Silic, C.; Mukhtar, S.A.; et al. Long-term food insecurity, hunger and risky food acquisition practices: A cross-sectional study of food charity recipients in an Australian capital city. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Palermo, C.E.; Walker, K.Z.; Hill, P.; McDonald, J. The cost of healthy food in rural Victoria. Rural Remote Health 2008, 8, 1704. [Google Scholar]

- Cassady, D.; Jetter, K.M.; Culp, J. Is price a barrier to eating more fruits and vegetables for low-income families? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, P.A.; Rutishauser, I.H.; Cahill, M. Food in low-income families. Aust. J. Public Health 1992, 16, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, J.; Fitzgerald, A.P.; Layte, R.; Lutomski, J.; Molcho, M.; Perry, I.J. Sociodemographic, health and lifestyle predictors of poor diets. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2166–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorton, D.; Bullen, C.R.; Mhurchu, C.N. Environmental influences on food security in high-income countries. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, R.; Lawrence, M.; Gold, L.; Friel, S.; Pegram, O. Food insecurity in Australia: Implications for general practitioners. Aust. Fam. Physician 2015, 44, 859–862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Ralston, R.A.; Truby, H. Influence of food cost on diet quality and risk factors for chronic disease: A systematic review. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 68, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacka, F.N.; Berk, M. Depression, diet and exercise. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, S21–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parletta, N.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Cho, J.; Wilson, A.; Bogomolova, S.; Villani, A.; Itsiopoulos, C.; Niyonsenga, T.; Blunden, S.; Meyer, B.; et al. A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greaves, C.J.; Sheppard, K.E.; Abraham, C.; Hardeman, W.; Roden, M.; Evans, P.H.; Schwarz, P. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradley, J.P. The Ethnographic Interview; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reicks, M.; Kocher, M.; Reeder, J. Impact of cooking and home food preparation interventions among adults: A systematic review (2011–2016). J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 148–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contento, I.R.; Randell, J.S.; Basch, C.E. Review and analysis of evaluation measures used in nutrition education intervention research. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2002, 34, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Dhaliwal, S. Evaluation tool development for food literacy programs. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Session | Lesson Outline | Teaching Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Module 1: Eat for variety |

|

|

| Module 2: Eat for Wellbeing |

|

|

| Module 3: Eat for Balance |

|

|

| Module 4: Eat for the Environment |

|

|

| Module 5: Eat for Choice | The charitable agency staff and NEST participants choose from the following modules:

|

|

| Module 6: Eat for Life |

|

|

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 9 (42.9) |

| Female | 12 (57.1) |

| Age | |

| 18–34 years | 6 (28.6) |

| 35–54 years | 10 (47.6) |

| 55–74 years | 5 (23.8) |

| Employment Status | |

| Employed | 3 (14.3) |

| Employed—unpaid | 1 (4.7) |

| Unemployed | 17 (81.0) |

| Education Level | |

| Did not finish high school | 9 (42.9) |

| Year 12 or equivalent | 5 (23.8) |

| Non-tertiary education | 5 (23.8) |

| Tertiary education | 2 (9.5) |

| Housing Structure | |

| Family with dependent children | 3 (14.3) |

| Couple only | 1 (4.8) |

| Lone person | 5 (23.8) |

| Group household | 12 (57.1) |

| Living Situation | |

| Homeowner/renter/resident of social housing | 10 (47.6) |

| Resident of assisted living facility/residential care accommodation | 4 (19.1) |

| Resident of short-term emergency care | 7 (33.3) |

| Number of people living in usual residence | |

| 1–2 people | 6 (28.6) |

| 3–5 people | 2 (9.5) |

| 6+people | 13 (61.9) |

| Meal preparation and frequency | |

| Prepare no meals | 2 (9.5) |

| Prepare some meals | 11 (52.4) |

| Prepare most meals | 4 (19.1) |

| Prepare all meals | 4 (19.1) |

| Food Security Scores | Pre n (%) | Post n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Individual 6-item scores | ||

| Ran out of food | 13 (61.9) | 9 (42.9) |

| Couldn’t afford healthy meals | 12 (57.1) | 14 (66.7) |

| Adults cut size or skipped meals | 7 (33.3) | 3 (14.3) |

| Frequency adults cut/skipped meals | 5 (23.8) | 2 (9.5) |

| Ate less than thought should | 8 (38.1) | 5 (23.8) |

| Hungry but didn’t eat | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.5) |

| Level of severity scores | ||

| High or marginal food security (0–1) | 8 (38.1) | 12 (57.1) |

| Low or very low food security total (2–6) | 13 (61.9) | 9 (42.9) |

| - Low food security (2–4) | 10 (47.6) | 7 (33.4) |

| - Very low food security (5–6) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.5) |

| Food Literacy Measure | Pre Mean (±SD) | Post Mean (±SD) | p Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking confidence (Scale of 1–Not confident to 5–extremely confident) | |||

| Combined average cooking confidence score | 3.10 (0.56) | 3.76 (0.63) | <0.001 * |

| Confidence to eat the recommended servings of fruit and vegetables each day | 2.67 (0.73) | 3.42 (0.93) | 0.009 * |

| Confidence in ability to buy healthy food on a budget | 3.19 (1.08) | 3.57 (1.61) | 0.194 |

| Confidence to cook from basic ingredients | 3.33 (0.97) | 3.95 (1.12) | 0.014 * |

| Confidence in following a simple recipe | 3.29 (0.20) | 4.00 (0.22) | 0.002 * |

| Confidence in tasting foods not eaten before | 3.05 (1.16) | 3.86 (0.96) | 0.005 * |

| Confidence in preparing and cooking new foods and recipes | 3.05 (0.67) | 3.76 (0.89) | 0.001 * |

| Food behaviours on a scale of 0 (never) to 3 (always) | |||

| Combined average food behaviours score | 1.39 (0.62) | 1.76 (0.70) | 0.006 * |

| Look for low-salt food varieties | 0.81 (1.03) | 1.47 (1.03) | 0.007 * |

| Choose wholemeal or wholegrain bread | 1.48 (1.03) | 1.95 (1.02) | 0.030 * |

| Read nutrition information panels when shopping | 1.05 (0.97) | 1.76 (0.94) | 0.004 * |

| Read ingredient list when shopping | 1.24 (1.14) | 1.57 (0.93) | 0.186 |

| Look at price per kilo when shopping | 2.05 (0.92) | 2.14 (0.96) | 0.676 |

| Change recipes to make them healthier | 1.34 (1.02) | 1.52 (0.87) | 0.238 |

| Add salt to food when cooking | 1.71 (1.23) | 1.67 (0.91) | 0.740 |

| Use a shopping list | 1.48 (0.98) | 2.00 (0.92) | 0.012 * |

| Nutrition knowledge (score 0–5) | |||

| Average total nutrition knowledge score | 2.57 (0.98) | 3.09 (0.89) | 0.033 * |

| Foods and Beverages | Pre Mean (±SD) | Post Mean (±SD) | p Value 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit, vegetables, and water | |||

| Vegetables | 1.71 (1.07) | 2.36 (1.45) | 0.043 * |

| Fruit | 1.55 (0.97) | 1.83 (1.08) | 0.209 |

| Water | 5.05 (3.22) | 4.90 (3.10) | 0.860 |

| Discretionary beverages | |||

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 1.24 (1.46) | 0.83 (0.89) | 0.017 * |

| Discretionary foods | |||

| Overall discretionary foods | 1.72 (1.22) | 1.28 (1.05) | 0.140 |

| Potato crisps or salty snack foods | 0.28 (0.29) | 0.16 (0.22) | 0.011 * |

| Chocolate or lollies | 0.54 (0.75) | 0.47 (0.72) | 0.805 |

| Cake, doughnuts, sweet biscuits | 0.38 (0.42) | 0.27 (0.33) | 0.184 |

| Pies, pasties, sausage rolls | 0.36 (0.29) | 0.24 (0.32) | 0.155 |

| Fast foods (e.g., McDonalds, KFC) | 0.11 (0.12) | 0.09 (0.17) | 0.050 |

| Pizza (shop bought or homemade) | 0.06 (0.62) | 0.06 (0.42) | 0.661 |

| Category | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 11 (64.7) |

| Female | 6 (35.3) |

| Age | |

| 18–34 years | 3 (17.7) |

| 35–54 years | 9 (52.9) |

| 55–74 years | 4 (23.5) |

| 75+ years | 1 (5.9) |

| Nationality | |

| Australian | 12 (70.6) |

| Non-Australian | 5 (29.4) |

| Primary Language | |

| English | 17 (100) |

| Non-English | 0 (0) |

| Housing Status | |

| Housing Commission | 6 (35.3) |

| Rehabilitation Centre | 5 (29.4) |

| Renting | 4 (23.5) |

| Homeowner | 2 (11.8) |

| Children in home | |

| 0 | 16 (94.1) |

| 1–5 | 1 (5.9) |

| Other adults in home | |

| 0 | 4 (23.5) |

| 1–5 | 3 (17.7) |

| 6+ | 10 (58.8) |

| Weekly household income | |

| <$575 | 11 (64.7) |

| $575–865 | 2 (11.7) |

| $865–1150 | 1 (5.9) |

| >$1150 | 1 (5.9) |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (11.8) |

| Food security level | |

| High or marginal food security (0–1) | 9 (53.0) |

| Low or very low food security total (2–6) | 8 (47.0) |

| Low food security (2–4) | 4 (23.5) |

| Very low food security (5–6) | 4 (23.5) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

West, E.G.; Lindberg, R.; Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A. The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy—OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082197

West EG, Lindberg R, Ball K, McNaughton SA. The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy—OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients. 2020; 12(8):2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082197

Chicago/Turabian StyleWest, Elisha G., Rebecca Lindberg, Kylie Ball, and Sarah A. McNaughton. 2020. "The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy—OzHarvest’s NEST Program" Nutrients 12, no. 8: 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082197

APA StyleWest, E. G., Lindberg, R., Ball, K., & McNaughton, S. A. (2020). The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy—OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients, 12(8), 2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082197