Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chemical Constituents of Garlic

3. Pharmacokinetics and Stability of Garlic Components

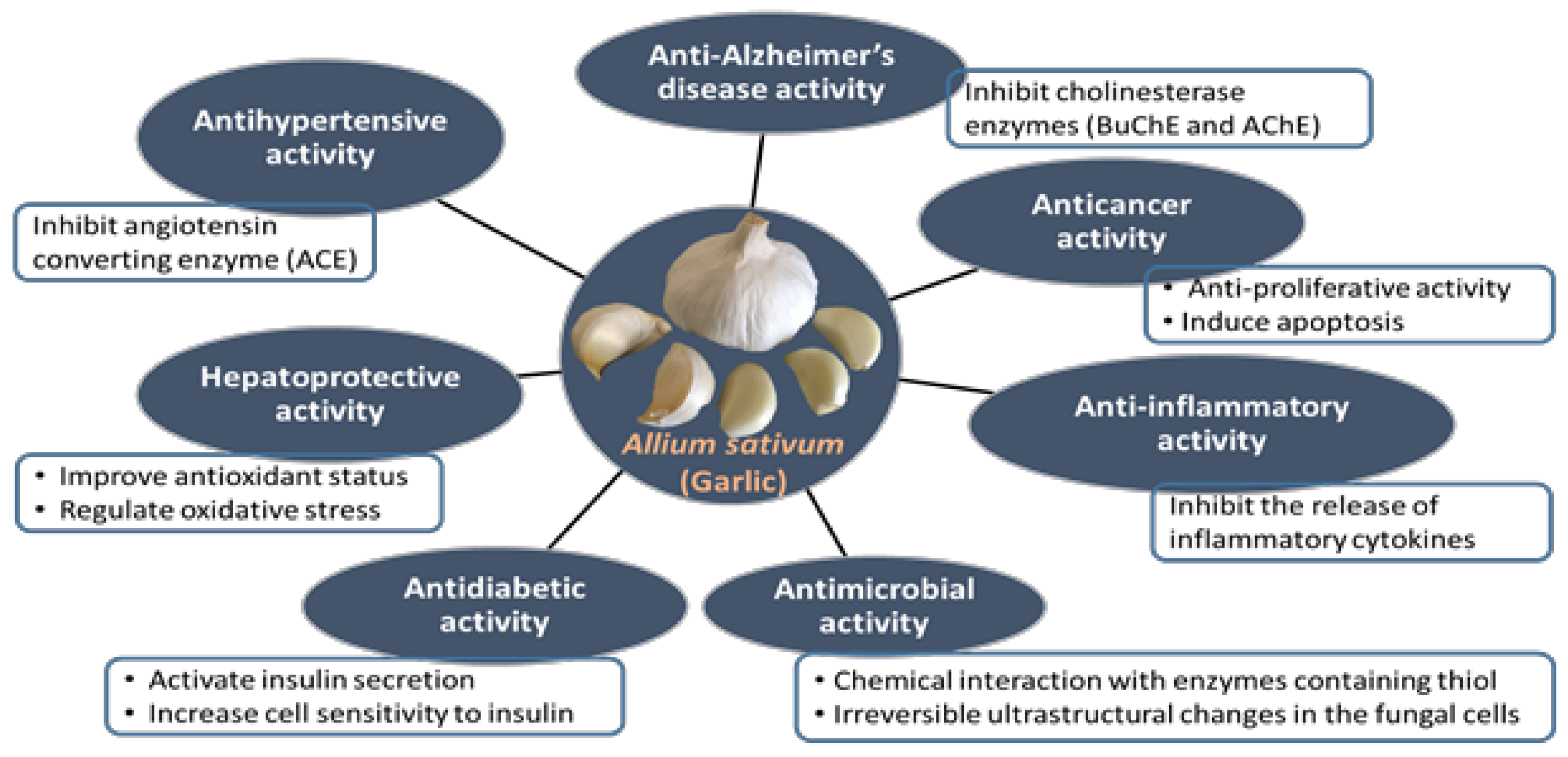

4. Pharmacological Activities of Garlic and Its Related Compounds

4.1. Traditional Uses of Garlic

4.2. Activities Related to Infectious Diseases

4.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

4.2.2. Antifungal Activity

4.2.3. Anti-Protozoal Activity

4.2.4. Antiviral Activity

4.3. Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activities

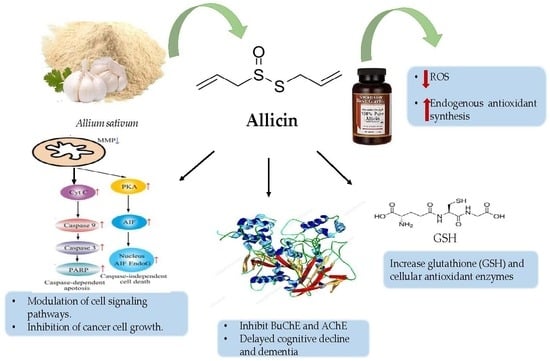

4.3.1. Antioxidant Activity

4.3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.4. Anticancer Activity

4.5. Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Activity

4.6. Activities Related to Metabolic Diseases

4.6.1. Effect on Dyslipidemia

4.6.2. Effect on Diabetes Mellitus

4.6.3. Effect on Obesity

4.6.4. Antihypertensive Activity

4.7. Recommended Dose and Toxic Side Effects of Garlic

4.7.1. Recommended Dose

4.7.2. Adverse Effects and Toxicity

5. Combination Therapy with Other Drugs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGE | aged garlic extract |

| PCSO | S-propyl cysteine-sulfoxide |

| MCSO | S-methyl cysteine-sulfoxide |

| NAC | N-Acetylcysteine |

| SAC | S-Allyl-cysteine |

| SAMC | S-ally-mercapto cysteine |

| PLP | pyridoxal phosphate |

| DAS | Diallyl sulfide |

| DADS | Diallyl disulfide |

| DATS | Diallyl trisulfide |

| AMS | Allyl methyl sulfide |

| AMDS | allyl methyl disulfide |

| SGF | simulated gastric fluid |

| SIF | stimulated intestinal fluid |

| HCMV | Human Cytomegalovirus |

| NK-cell | Natural killer-cell |

| ORS | oxygen-free radical species |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase |

| GCLM | glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 subunit |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythrobia-2 related factor 2 |

| ARE | antioxidant response element |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| RANKL | receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand |

| ABG | Aged black garlic |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| PGE2 | prostaglandin E2 |

| TLR4 | toll-like receptor 4 |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| GBM CSC | Glioblastoma multiforme cancer stem cells |

| AChE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| Ach | acetylcholine |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| BuChE | butyrylcholinesterase |

| TG | triglyceride |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| UCP | mitochondrial inner membrane proteins |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| NO | nitric oxide; H2S: hydrogen sulphide |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| RBCs | red blood cells |

| ACE | Angiotensin-converting enzyme |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

References

- Ríos, J.L.; Recio, M.C. Medicinal plants and antimicrobial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 100, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beshbishy, A.M.; Batiha, G.E.S.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Inhibitory effects of methanolic Olea europaea and acetonic Acacia laeta on the growth of Babesia and Theileria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2019, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.A.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Shaheen, M.H.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Inhibitory effects of Syzygium aromaticum and Camellia sinensis methanolic extracts on the growth of Babesia and Theileria parasites. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2019, 10, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.A.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Nadwa, E.; Rashwan, E.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Safety and efficacy of hydroxyurea and eflornithine against most blood parasites Babesia and Theileria. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228996. [Google Scholar]

- Batiha, G.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K.; El-Mleeh, A.; Igarashi, I. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis, phytochemical screening and antiprotozoal effects of the methanolic Viola tricolor and acetonic Laurus nobilis extracts. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Shaheen, H.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Evaluation of the inhibitory effect of ivermectin on the growth of Babesia and Theileria parasites in vitro and in vivo. Trop. Med. Health 2019, 47, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essawi, T.; Srour, M. Screening of some Palestinian medicinal plants for antibacterial activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2000, 70, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Shaheen, H.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. The effects of trans-chalcone and chalcone 4 hydrate on the growth of Babesia and Theileria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshbishy, A.M.; Batiha, G.E.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Ellagic acid microspheres restrict the growth of Babesia and Theileria in vitro and Babesia microti in vivo. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.A.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Anti-piroplasmic potential of the methanolic Peganum harmala seeds and ethanolic Artemisia absinthium leaf extracts. J. Protozool. Res. 2019, 29, 8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Batiha, G.-S.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Adeyemi, O.S.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.M.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Elkelish, A.A.; Igarashi, I. Phytochemical screening and antiprotozoal effects of the methanolic Berberis vulgaris and acetonic Rhus coriaria extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman, H.J.; Deans, S.G. Antimicrobial agents from plants: Antibacterial activity of plant volatile oils. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.-S.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K.; Beshbishy, A.M. Physostigmine: A plant alkaloid isolated from Physostigma venenosum: A review on pharmacokinetics, pharmacological and toxicological activities. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2020, 10, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakkali, F.; Averbeck, S.; Averbeck, D.; Idaomar, M. Biological effects of essential oils—A review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 446–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batiha, G.-S.; Alkazmi, L.M.; Wasef, L.G.; Beshbishy, A.M.; Nadwa, E.H.; Rashwan, E.K. Syzygium aromaticum L. (Myrtaceae): Traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents, pharmacological and toxicological activities. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaz, E.; Alposy, H.C. Garlic (Allium sativum) and traditional medicine. Turkiye Parazitolojii Derg. 2007, 31, 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Badal, D.S.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Singh, S.; Prakash, A.; Verma, S.; Kumar, J. Effect of organic manures and inorganic fertilizers on growth, yield and its attributing traits in garlic (Allium sativum L.). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2019, 8, 587–590. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, J.; Anderson, L.A.; Phillipson, J.D. Herbal Medicines, 2nd ed.; Pharmaceutical Press: London, UK, 2002; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K. Historical perspective on garlic and cardiovascular disease. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 977S–979S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.; Biju, R. Neuroprotective effects of garlic a review. Libyan J. Med. 2008, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jaber, N.A.; Awaad, A.S.; Moses, J.E. Review some antioxidant plants growing in Arab world. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2011, 15, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanwimolruk, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. Cytochrome P450 enzyme mediated herbal drug interactions (Part 1). EXCLI J. 2014, 13, 347–391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Slusarenko, A.J.; Patel, A.; Portz, D. Control of plant diseases by natural products: Allicin from garlic as a case study. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2008, 121, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. Allicin and other functional active components in garlic: Health benefits and bioavailability. Int. J. Food Prop. 2007, 10, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, A.D.; De Witt, B.J.; Anwar, M.; Smith, D.E.; Feng, C.J.; Kadowitz, P.J.; Nossaman, B.D. Analysis of responses of garlic derivatives in the pulmonary vascular bed of the rat. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawson, L.D.; Gardner, C.D. Composition, stability, and bioavailability of garlic products used in a clinical trial. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 6254–6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rishton, G.M. Natural products as a robust source of new drugs and drug leads: Past successes and present day issues. Am. J. Cardiol. 2008, 101, S43–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batiha, G.E.S.; Beshbishy, A.A.; Tayebwa, D.S.; Shaheen, M.H.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Inhibitory effects of Uncaria tomentosa bark, Myrtus communis roots, Origanum vulgare leaves and Cuminum cyminum seeds extracts against the growth of Babesia and Theileria in vitro. Jpn. J. Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sobolewska, D.; Podolak, I.; Makowska-Wąs, J. Allium ursinum: Botanical, phytochemical and pharmacological overview. Phytochem. Rev. 2015, 14, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Snafi, A. Pharmacological effects of Allium species grown in Iraq. An overview. Int. J. Pharm. Health Care Res. 2013, 1, 132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Pu, X.; Du, J.; Yang, X.; Yang, T.; Yang, S. Therapeutic role of functional components in Alliums for preventive chronic disease in human being. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 9402849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, G.A.; Ebaid, G.X.; Seiva, F.R.; Rocha, K.H.; Galhardi, C.M.; Mani, F.; Novelli, E.L. N-acetylcysteine an Allium plant compound improves high-sucrose diet-induced obesity and related effects. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 643269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asdaq, S.M.B.; Inamdar, M.N. Pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions of propranolol with garlic (Allium sativum) in rats. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 824042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, G.B.; Dam, S.M.; Le, N.T.T. Amelioration of single clove black garlic aqueous extract on dyslipidemia and hepatitis in chronic carbon tetrachloride intoxicated Swiss Albino mice. Int. J. Hepatol. 2018, 2018, 9383950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yan, J.; Han, X.; Hu, W. Garlic-derived compound S-allylmercaptocysteine (SAMC) is active against anaplastic thyroid cancer cell line 8305C (HPACC). Technol. Health Care 2015, 23, S89–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Cao, L.; Ding, L.; Bian, J.S. A new hope for a devastating disease: Hydrogen sulfide in Parkinson’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 55, 3789–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, T.; Rabinkov, A.; Mirelman, D.; Wilchek, M.; Weiner, L. The mode of action of allicin: Its ready permeability through phospholipid membranes may contribute to its biological activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1463, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlinghaus, J.; Albrecht, F.; Gruhlke, M.C.; Nwachukwu, I.D.; Slusarenko, A.J. Allicin: Chemistry and biological properties. Molecules 2014, 19, 12591–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimon, L.J.; Rabinkov, A.; Shin, I.; Miron, T.; Mirelman, D.; Wilchek, M.; Frolow, F. Two structures of alliinase from Allium sativum L.: Apo form and ternary complex with aminoacrylate reaction intermediate covalently bound to the PLP cofactor. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 366, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rooij, B.M.; Boogaard, P.J.; Rijksen, D.A.; Commandeur, J.N.; Vermeulen, N.P. Urinary excretion of N-acetyl-S-allyl-L-cysteine upon garlic consumption by human volunteers. Arch. Toxicol. 1996, 70, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, F.; Kodera, Y. Garlic chemistry: Stability of S-(2-propenyl)-2-propene-1-sulfinothioate (Allicin) in blood, solvents, and simulated physiological fluids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 2332–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, D.P.; Stojanović, S.; Najman, S.; Nikolić, V.D.; Stanojević, L.P.; Tačić, A.; Nikolić, L.B. Biological evaluation of synthesized allicin and its transformation products obtained by microwaves in methanol: Antioxidant activity and effect on cell growth. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, M.; Ali, M. Garlic [Allium sativum]: A review of its potential use as an anti-cancer agent. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2003, 3, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuda, T.; Iwai, A.; Yano, T. Effect of red pepper Capsicum annuum var. conoides and garlic Allium sativum on plasma lipid levels and cecal microflora in mice fed beef tallow. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2004, 42, 1695–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, A.; Mengesha, W. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of garlic (Allium Sativum) and its biological active compounds. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Technol. 2015, 1, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, K.; Lowe, G.M. Garlic and cardiovascular disease: A critical review. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 736s–740s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.R. An overview of the antifungal properties of allicin and its breakdown products-the possibility of a safe and effective antifungal prophylactic. Mycoses 2005, 48, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, Z.M.; O’Gara, E.A.; Hill, D.J.; Sleightholme, H.V.; Maslin, D.J. Antimicrobial properties of garlic oil against human enteric bacteria: Evaluation of methodologies and comparisons with garlic oil sulfides and garlic powder. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, R.; Wilson, P. Antibacterial activity of a new, stable, aqueous extract of allicin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2004, 61, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallock-Richards, D.; Doherty, C.J.; Doherty, L.; Clarke, D.J.; Place, M.; Govan, J.R.; Campopiano, D.J. Garlic revisited: Antimicrobial activity of allicin-containing garlic extracts against Burkholderia cepacia complex. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikaili, P.; Maadirad, S.; Moloudizargari, M.; Aghajanshakeri, S.; Sarahroodi, S. Therapeutic uses and pharmacological properties of garlic, shallot, and their biologically active compounds. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2013, 16, 1031–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Meriga, B.; Mopuri, R.; MuraliKrishna, T. Insecticidal, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of bulb extracts of Allium sativum. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2012, 5, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrzadeh, M.; Ebadi, A.G. Antibacterial effect of garlic (Allium sativum L.) on Staphylococcus aureus. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2006, 9, 1577–1579. [Google Scholar]

- Gruhlke, M.C.; Nwachwukwu, I.; Arbach, M.; Anwar, A.; Noll, U.; Slusarenko, A.J. Allicin from garlic, effective in controlling several plant diseases, is a reactive sulfur species (RSS) that pushes cells into apoptosis. In Proceedings of the Modern fungicides and antifungal compounds VI. 16th International Reinhardsbrunn Symposium, Friedrichroda, Germany, 25–29 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pârvu, M.; Moţ, C.A.; Pârvu, A.E.; Mircea, C.; Stoeber, L.; Roşca-Casian, O.; Ţigu, A.B. Allium sativum extract chemical composition, antioxidant activity and antifungal effect against Meyerozyma guilliermondii and Rhodotorula mucilaginosa causing onychomycosis. Molecules 2019, 24, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fufa, B. Anti-bacterial and anti-fungal properties of garlic extract (Allium sativum): A review. Microbiol. Res. J. Int. 2019, 28, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, S.T.; Platt, M.W. Antifungal effects of Allium sativum (garlic) extract against the Aspergillus species involved in otomycosis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1995, 20, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, H.; Fang, F.; Ye, D.Y.; Shu, S.N.; Zhou, Y.F.; Dong, Y.S.; Nie, X.C.; Li, G. Experimental study on the action of allitridin against human cytomegalovirus in vitro: Inhibitory effects on immediate-early genes. Antiviral Res. 2006, 72, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Ghaffar, F.; Semmler, M.; Al-Rasheid, K.A.; Strassen, B.; Fischer, K.; Aksu, G.; Klimpel, S.; Mehlhorn, H. The effects of different plant extracts on intestinal cestodes and on trematodes. Parasitol. Res. 2011, 108, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hafeez, E.H.; Ahmad, A.K.; Kamal, A.M.; Abdellatif, M.Z.; Abdelgelil, N.H. In vivo antiprotozoan effects of garlic (Allium sativum) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts on experimentally infected mice with Blastocystis spp. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 3439–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallwitz, H.; Bonse, S.; Martinez-Cruz, A.; Schlichting, I.; Schumacher, K.; Krauth-Siegel, R.L. Ajoene is an inhibitor and subversive substrate of human glutathione reductase and Trypanosoma cruzi trypanothione reductase: Crystallographic, kinetic, and spectroscopic studies. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazaa, I.K.K.; Al-Taai, N.A.; Khalil, N.K.; Zakri, A.M.M. Efficacy of garlic and onion oils on murin experimental Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Al-Anbar J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Gruhlke, M.C.; Nicco, C.; Batteux, F.; Slusarenko, A.J. The effects of allicin, a reactive sulfur species from garlic, on a selection of mammalian cell lines. Antioxidants 2016, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawai, T.; Itoh, Y.; Ozaki, H.; Isoda, N.; Okamoto, K.; Kashima, Y.; Kawaoka, Y.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kida, H.; Ogasawara, K. Induction of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte and antibody responses against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus infection in mice by inoculation of a pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus particles inactivated with formalin. Immunology 2008, 124, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Yoon, D.K.; Ji, D.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.H. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of fresh garlic and aged garlic by-products extracted with different solvents. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, W.; Yang, M.L.; Liu, L.X.; Huang, S.X.; Tao, L.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.S. Investigation of the dynamic changes in the chemical constituents of Chinese “laba” garlic during traditional processing. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 41872–41883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, J.; Dou, C.; Li, N.; Kang, F.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yang, X.; Dong, S. Alliin attenuated RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by scavenging reactive oxygen species through inhibiting Nox1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, A.; Cao, S.Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Tang, G.Y.; Corke, H.; Mavumengwana, V.; Li, H.B. Bioactive compounds and biological functions of garlic (Allium sativum L.). Foods 2019, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Shaheen, H.M.; Abushouk, A.I.; Toraih, E.A.; Fawzy, M.S.; Alansari, W.S.; Aleya, L.; Bungau, S. Thymoquinone and diallyl sulfide protect against fipronil-induced oxidative injury in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res Int. 2018, 25, 23909–23916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.A.; El-Sayed, B.A.; El-Sayed, L.H. Development of immunization trials against Eimeria spp. Trials Vaccinol. 2016, 5, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobauer, R.; Frass, M.; Gmeiner, B.; Kaye, A.D.; Frost, E.A. Garlic extract (Allium sativum) reduces migration of neutrophils through endothelial cell monolayers. Middle East J. Anaesthesiol. 2000, 15, 649–658. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Wu, H.; Fu, P. Allicin attenuates inflammation and suppresses HLA-B27 protein expression in ankylosing spondylitis mice. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 171573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.Y.; Ryu, J.H.; Shin, J.H.; Kang, M.J.; Kang, J.R.; Han, J.; Kang, D. Comparison of anti-Oxidant and anti-Inflammatory effects between fresh and aged black garlic extracts. Molecules 2016, 21, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, B.R.; Yoo, J.M.; Baek, S.Y.; Kim, M.R. Anti-inflammatory effect of aged black garlic on 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate-induced dermatitis in mice. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2019, 13, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sela, U.R.; Ganor, S.; Hecht, I.; Brill, A.; Miron, T.; Rabinkov, A.; Wilchek, M.; Mirelman, D.; Lider, O.; Hershkoviz, R. Allicin inhibits SDF-1α-induced T cell interactions with fibronectin and endothelial cells by down-regulating cytoskeleton rearrangement, Pyk-2 phosphorylation and VLA-4 expression. Immunology 2004, 111, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Abushouk, A.I.; Bungău, S.G.; Bin-Jumah, M.; El-Kott, A.F.; Shati, A.A.; Aleya, L.; Alkahtani, S. Protective effects of thymoquinone and diallyl sulphide against malathion-induced toxicity in rats. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Kim, J.A.; Choi, D.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Jung, H.S.; Hong, J.T. Anti-inflammatory and anti-amyloidogenic effects of a small molecule, 2,4-bis(p-hydroxyphenyl)-2-butenal in Tg2576 Alzheimer’s disease mice model. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Le, W.; Cui, Z. A novel therapeutic anticancer property of raw garlic extract via injection but not ingestion. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabria, S.V.; Akbarsha, M.A.; Li, A.P.; Kharkar, P.S.; Desai, K.B. In situ allicin generation using targeted alliinase delivery for inhibition of MIA PaCa-2 cells via epigenetic changes, oxidative stress and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKI) expression. Apoptosis 2015, 20, 1388–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Duan, W.; Feng, C.; He, X. Allicin induces apoptosis of the MGC-803 human gastric carcinoma cell line through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase/caspase-3 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 11, 2755–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager-Khoutorsky, M.; Goncharov, I.; Rabinkov, A.; Mirelman, D.; Geiger, B.; Bershadsky, A.D. Allicin inhibits cell polarization, migration and division via its direct effect on microtubules. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2007, 64, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.V.; Pal, R.; Vaiphei, K.; Sharma, S.K.; Ola, R.P. Garlic in health and disease. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2011, 24, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iciek, M.; Kwiecień, I.; Chwatko, G.; Sokołowska-Jeżewicz, M.; Kowalczyk-Pachel, D.; Rokita, H. The effects of garlic-derived sulfur compounds on cell proliferation, caspase 3 activity, thiol levels and anaerobic sulfur metabolism in human hepatoblastoma HepG2 cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2012, 30, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Belloir, C.; Siess, M.H.; Le Bon, A.M. Inhibition of carcinogen-induced DNA damage in rat liver and colon by garlic powders with varying alliin content. Nutr. Cancer 2006, 55, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischauer, A.T.; Arab, L. Garlic and cancer: A critical review of the epidemiologic literature. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1032s–1040s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piscitelli, S.C.; Burstein, A.H.; Welden, N.; Gallicano, K.D.; Falloon, J. The effect of garlic supplements on the pharmacokinetics of saquinavir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayan, L.; Koulivand, P.H.; Gorji, A. Garlic: A review of potential therapeutic effects. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2014, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- VinayKumar, D.K. Robbins Basic Pathology/[Edited by] Vinay Kumar, Ramzi S. Cotran, Stanley L. Robbins; with Illustrations by James A. Perkins; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Acqua, S.; Maggi, F.; Minesso, P.; Salvagno, M.; Papa, F.; Vittori, S.; Innocenti, G. Identification of non-alkaloid acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from Ferulago campestris (Besser) Grecescu (Apiaceae). Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 1208–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.H.; Wu, J.W.; Liu, H.L.; Zhao, J.H.; Liu, K.T.; Chuang, C.K.; Lin, H.Y.; Tsai, W.B.; Ho, Y. The discovery of potential acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: A combination of pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening, and molecular docking studies. J. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 18, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, A.J.; Lekan Faboya, A.P.; Awonegan, I.O.; Anadozie, S.; Oluwasola, T.A. Antioxidant and anti-Acetylcholinesterase activities of essential oils from garlic (Allium sativum) Bulbs. Int. J. Plant Res. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Shukla, R.; Prakash, B.; Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Mishra, P.K.; Dubey, N.K. Chemical profile, antifungal, antiaflatoxigenic and antioxidant activity of Citrus maxima Burm. and Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck essential oils and their cyclic monoterpene, DL-limonene. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1734–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borek, C. Garlic reduces dementia and heart-disease risk. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 810S–812S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.; McNeil, B.; Taylor, C.; Holl, G.; Ruff, D.; Gwebu, E. Effect of aged garlic extract on human recombinant caspace-3 activity. J. Ala. Acad. Sci. 2003, 74, 121–122. [Google Scholar]

- Mbyirukira, G.; Gwebu, E.T. Aged garlic extract protects serum-deprived PC12 cells from apoptosis. J. Ala. Acad. Sci. 2003, 74, 127–128. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, S.; Naz, N.; Khaliq, S.; Perveen, T.; Haleem, D.J. Repeated administration of fresh garlic increases memory retention in rats. J. Med. Food 2008, 11, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, D.; Banerjee, S. Learning and memory promoting effects of crude garlic extract. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 51, 1094–1100. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S. Dual inhibition of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase enzymes by allicin. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2015, 47, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, D.B. Progress update: Pharmacological treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2007, 3, 569–578. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B.; Bernhardt, T.; Moeller, H.J.; Heuser, I.; Frölich, L. Combination therapy in Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Drugs 2004, 18, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weggen, S.; Eriksen, J.L.; Das, P.; Sagi, S.A.; Wang, R.; Pietrzik, C.U.; Findlay, K.A.; Smith, T.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Bulter, T.; et al. A subset of NSAIDs lower amyloidogenic Aβ42 independently of cyclooxygenase activity. Nature 2001, 414, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, C.B.; Shnyrov, V.L.; Newstead, S.; Shin, I.; Roth, E.; Silman, I.; Weiner, L. Stabilization of a metastable state of Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase by chemical chaperones. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2337–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, F. The tolerability and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 2002, 127, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jann, M.W.; Shirley, K.L.; Small, G.W. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cholinesterase inhibitors. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2002, 41, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.G.; Ren, P.Y.; Wang, G.Y.; Yao, S.X.; He, X.J. Allicin protects spinal cord neurons from Glutamate-induced oxidative stress through regulating the heat shock protein 70/inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway. Food Funct. 2015, 6, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseini, A.; Hosseinzadeh, H. A review on the effects of Allium sativum (Garlic) in metabolic syndrome. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2015, 38, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qidwai, W.; Ashfaq, T. Role of garlic usage in cardiovascular disease prevention: An evidence-based approach. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 125649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iweala, E.E.; Akubugwo, E.I.; Okeke, C.U. Effect of ethanolic extracts of Allium sativum Linn. Liliaceae on serum cholesterol and blood sugar levels of alibino rabbits. Plant Prod. Res. J. 2005, 9, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.H.; Efendy, J.L.; Smith, N.J.; Campbell, G.R. Molecular basis by which garlic suppresses atherosclerosis. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 1006S–1009S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobenin, I.A.; Nedosugova, L.V.; Filatova, L.V.; Balabolkin, M.I.; Gorchakova, T.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Metabolic effects of time-released garlic powder tablets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: The results of double-blinded placebo-controlled study. Acta Diabetol. 2008, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobenin, I.A.; Pryanishnikov, V.V.; Kunnova, L.M.; Rabinovich, Y.A.; Martirosyan, D.M.; Orekhov, A.N. The effects of time-released garlic powder tablets on multifunctional cardiovascular risk in patients with coronary artery disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2010, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, R.; Aamir, K.; Shaikh, A.R.; Ahmed, T. Effects of garlic on dyslipidemia in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Ayub. Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2005, 17, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, D.K.; Prasad, S.K.; Kumar, R.; Hemalatha, S. An overview on antidiabetic medicinal plants having insulin mimetic property. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroughi, F.; Mohammad-Alizadeh Charandabi, S.; Javadzadeh, Y.; Mirghafourvand, M. Effects of garlic pill on blood glucose level in borderline gestational diabetes mellitus: A triple blind, randomized clinical trial. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2018, 20, e60675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, B.; Zhang, C.; Sheng, Y.; Zhao, C.; He, X.; Xu, W.; Huang, K.; Luo, Y. Hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic effect of S-allyl-cysteine sulfoxide (alliin) in DIO mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.S.; Kim, I.H.; Kim, C.T.; Kim, Y. Reduction of body weight by dietary garlic is associated with an increase in uncoupling protein mRNA expression and activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in diet-induced obese mice. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1947–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.Y.; Ki, S.H.; Kim, Y.W.; Noh, K.; Lee da, Y.; Kang, B.; Ryu, J.H.; Jeon, R.; Kim, E.H.; Hwang, S.J.; et al. Ajoene, a stable garlic by-product, inhibits high fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and oxidative injury through LKB1-dependent AMPK activation. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keophiphath, M.; Priem, F.; Jacquemond-Collet, I.; Clément, K.; Lacasa, D. 1,2-Vinyldithiin from garlic inhibits differentiation and inflammation of human preadipocytes. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2055–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.; Budoff, M.J. Garlic and Heart Disease. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 416S–421S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobiova, H.; Thomson, M.; Al-Qattan, K.; Peltonen-Shalaby, R.; Al-Amin, Z.; Ali, M. Garlic increases antioxidant levels in diabetic and hypertensive rats determined by a modified peroxidase method. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2011, 2011, 703049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobenin, I.; Andrianova, I.; Ionova, V.; Karagodin, V.; Orekhov, A. Anti-aggregatory and fibrinolytic effects of time-released garlic powder tablets. Med. Health Sci. J. 2012, 10, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, H.; Singh, A.; Patole, A.M.; Tenpe, C.R. Antihypertensive effect of allicin in dexamethasone-induced hypertensive rats. Integr. Med. Res. 2017, 6, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ried, K.; Fakler, P. Potential of garlic (Allium sativum) in lowering high blood pressure: Mechanisms of action and clinical relevance. Integr. Blood Press. Control 2014, 7, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, K.; Lowe, G.M.; Smith, S. Aged garlic extract inhibits human platelet aggregation by altering intracellular signaling and platelet shape change. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 410S–415S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tattelman, E. Health effects of garlic. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 72, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asdaq, S.M.B.; Inamdar, M.N. The potential benefits of a garlic and hydrochlorothiazide combination as antihypertensive and cardioprotective in rats. J. Nat. Med. 2011, 65, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasek, A.; Bartoszek, A.; Namiesnik, J. Phytochemicals that counteract the cardiotoxic side effects of cancer chemotherapy. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2009, 63, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, B.; Monteiro, L.; Rocha, N. Allium species poisoning in dogs and cats. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Incl. Trop. Dis. 2011, 17, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.S.; Andrade, A.S.; Flexner, C. Interactions between natural health products and antiretroviral drugs: Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Izzo, A.A. Garlic (Allium sativum L.): Adverse effects and drug interactions in humans. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007, 51, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Xie, K.; Liu, Z.; Nakasone, Y.; Sakao, K.; Hossain, A.; Hou, D.X. Preventive effects and mechanisms of garlic on dyslipidemia and gut microbiome dysbiosis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuncu, M.; Eralp, A.; Celik, A. Effect of aged garlic extract against methotrexate-induced damage to the small intestine in rats. Phytother. Res. 2006, 20, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almogren, A.; Shakoor, Z.; Adam, M.H. Garlic and onion sensitization among Saudi patients screened for food allergy: A hospital-based study. Afr. Health Sci. 2013, 13, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Vafaei, S.A.; Moradi, M.N.; Ahmadi, M.; Pourjafar, M.; Oshaghi, E.A. Combination of ezetimibe and garlic reduces serum lipids and intestinal niemann-pick C1-like 1 expression more effectively in hypercholesterolemic mice. Avicenna J. Med. Biochem. 2015, 3, e23205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, M.Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zeng, M.Z.; He, F.Z.; Luo, Z.Y.; Luo, J.Q.; Wen, J.G.; Chen, X.P.; Zhou, H.H.; Zhang, W. Pharmacogenomics and herb-drug interactions: Merge of future and tradition. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 321091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badr, G.M.; Arafa, N.S. Synergetic effect of aged garlic extract and methotrexate on rheumatoid arthritis induced by collagen in male albino rats. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2020, 58, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, R.M.; Saleh, A.H.A.; Ali, K.S. GC-MS analysis and antibacterial activity of garlic extract with antibiotic. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2020, 8, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Vathsala, P.G.; Murthy, P.K. Immunomodulatory and antiparasitic effects of garlic–arteether combination via nitric oxide pathway in Plasmodium berghei-infected mice. J. Parasit. Dis. 2019, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beshbishy, A.M.; Batiha, G.E.-S.; Alkazmi, L.; Nadwa, E.; Rashwan, E.; Abdeen, A.; Yokoyama, N.; Igarashi, I. Therapeutic effects of atranorin towards the proliferation of Babesia and Theileria parasites. Pathogen 2020, 9, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compounds | Molecular formula | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Alliin | C6H11NO3S |  |

| Allicin | C6H10OS2 |  |

| E-Ajoene | C9H14OS3 |  |

| Z-Ajoene | C9H14OS3 |  |

| 2-Vinyl-4H-1,3-dithiin | C6H8S2 |  |

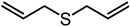

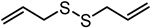

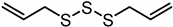

| Diallyl sulfide (DAS) | C6H10S |  |

| Diallyl disulfide (DADS) | C6H10S2 |  |

| Diallyl trisulfide (DATS) | C6H10S3 |  |

| Allyl methyl sulfide (AMS) | C4H8S |  |

| Activities | Bioactive Compound | Mechanism of Action | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterial | Allicin | Chemical interaction with enzymes containing thiol | [54] |

| Antifungal | DADS | Irreversible ultrastructural changes in the fungal cells, loss of structural integrity and affected the germination ability | [44] |

| DATS | |||

| Antiviral | Allicin | Chemical interaction with enzymes containing thiol | [58] |

| DATS | Enhancing Natural killer-cell (NK-cell) activity that destroys virus-infected cells | ||

| Antiprotozoal | Allicin | Preventing the parasite’s RNA, DNA and protein synthesis. | [58] |

| DATS | |||

| Ajoene | Inhibiting the human glutathione reductase and T. cruzi trypanothione reductase | [61] | |

| Antioxidant | Allicin, DADS, and DATS | Modulation of ROS, increasing glutathione and cellular antioxidant enzymes | [54] |

| Alliin | Controlling ROS generation and preventing mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) | [67] | |

| DAS | Suppressing the enzymatic activity of cytochrome P450-2E1, reducing the generation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species | [69] | |

| Anti-inflammatory | Allicin | Enhancing the immune cell activity f, inhibiting the SDF1α chemokine and Transendothelial migration of neutrophils | [60] |

| DAS | Diminishing the expression of the inflammatory cytokines (e.g., NF- κB, IL-1β, and TNF-α), and ROS generation by suppressing CYP-2E1 hepatic enzyme | [76] | |

| Thiacremonone | Blocking the NF-κB activity | [77] | |

| Anti-cancer | Allicin, alliin, DADS, DAS | Enhancing p38 expression and cleaved caspase 3. | [80] |

| Z-Ajoene | Stimulating apoptosis in human leukemic cells, promoting the peroxide production, caspase-3-like, and caspase-8 activities | [87] | |

| Immunomodulatory | Allicin | Suppressing BuChE and AChE | [105] |

| Anti-obesity | Ajoene | Decreasing the fat accumulation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and dramatically decreases the body weight gain | [117] |

| 1,2-Vinyldithiin | Decreasing the C/EBPα, PPARγ2, and LPL expression and the PPARγ effect in human adipocytes | [118] | |

| Antidiabetic | Allyl propyl disulfide, allicin, cysteine sulfoxide, and S-allyl cysteine sulfoxide, alliin | Decreasing the insulin secretion from pancreatic cells, increasing liver metabolism, and thus enhancing the short-acting insulin production | [114,115] |

| Hypolipidemic, hypocholesterolaemic | Different garlic preparations | Decreasing serum TC, TG, and LDL levels and moderately elevating HDL cholesterol | [107] |

| Anti-Atherosclerotic, antithrombotic | Different garlic preparations | Preventing ADP-activated platelets binding to immobilized fibrinogen and platelet aggregation, inhibiting GPIIb/IIIa receptor and increasing cAMP | [120] |

| Antihypertensive | Gamma-glutamylcysteine | Inhibiting the angiotensin-converting enzyme | [87] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; G. Wasef, L.; Elewa, Y.H.A.; A. Al-Sagan, A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Taha, A.E.; M. Abd-Elhakim, Y.; Prasad Devkota, H. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030872

El-Saber Batiha G, Magdy Beshbishy A, G. Wasef L, Elewa YHA, A. Al-Sagan A, Abd El-Hack ME, Taha AE, M. Abd-Elhakim Y, Prasad Devkota H. Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients. 2020; 12(3):872. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030872

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl-Saber Batiha, Gaber, Amany Magdy Beshbishy, Lamiaa G. Wasef, Yaser H. A. Elewa, Ahmed A. Al-Sagan, Mohamed E. Abd El-Hack, Ayman E. Taha, Yasmina M. Abd-Elhakim, and Hari Prasad Devkota. 2020. "Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review" Nutrients 12, no. 3: 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030872

APA StyleEl-Saber Batiha, G., Magdy Beshbishy, A., G. Wasef, L., Elewa, Y. H. A., A. Al-Sagan, A., Abd El-Hack, M. E., Taha, A. E., M. Abd-Elhakim, Y., & Prasad Devkota, H. (2020). Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Activities of Garlic (Allium sativum L.): A Review. Nutrients, 12(3), 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12030872