1. Introduction

In cell-based regenerative medicine, human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) are considered a promising major cell source, in conjunction with in vitro differentiation technology [

1,

2]. The hiPSCs can be engineered into numerous types of tissue, which provide a wide range of clinical applications, especially for the treatment of damaged and/or defective tissues and organs [

3,

4]. However, several issues remain to be overcome before hiPSCs can be applied clinically. During in vitro differentiation of hiPSCs, undifferentiated iPSCs still remain. These residual immature cells in the differentiated cell mixture present a risk with respect to the development of benign teratomas or aggressive teratocarcinomas after in vivo injection at the ectopic site [

5,

6]. Selective elimination of all residual undifferentiated hiPSCs, during differentiation or before implantation, is therefore crucial for the success of hiPSC-based cell therapy. However, considering the diversity of cell types for hPSC-based cell therapy, it would be hard to generalize that a certain approach is perfectly safe for the diverse types of differentiated cells. Thus, novel agents should be identified to ensure the efficacy of eliminating the undifferentiated cells as well as the safety of the desired differentiated cells for safe teratoma-free hPSC-based cell therapy [

7].

In many studies, herbal medicines have been shown to be useful adjuvants for the management of intractable diseases because of their high efficacy, minimal toxicity, and multi-modal activities [

8]. Our research group recently reported that Sagunja-tang, a traditional Korean herbal formula, significantly increased the efficiency of hiPSC generation by reprogramming human foreskin fibroblasts using transcription factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-myc) [

9]. However, herbal medicines that reduce the teratoma-forming activity of undifferentiated hiPSCs have not yet been reported.

Prunella vulgaris L. (PVL) is an important medicinal plant that is cultivated in Europe, Northeast Asia, and South Asia [

10,

11]. A dried flower stalk of PVL, Prunellae Spica (PS), has been used for treating hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, and hepatitis, and it exerts a variety of pharmacological activities, including antioxidant and anti-inflammation activities, regulation of the tumor metastatic microenvironment, and improvement of insulin sensitivity [

12,

13]. In addition, potent anti-cancer activities of PS have been shown in non-small cell lung cancer, T-cell lymphoma, and colon cancer [

14,

15]. Oral administration of PVL significantly improves the therapeutic efficacy of taxane, thus preventing the progression of breast cancer and reducing side effects such as anemia and neutrophil-reduced fever; this indicates that PVL may be a potential adjuvant for breast cancer chemotherapy [

16]. The main bioactive components of PS are phenylpropanoids (e.g., caffeic acid (CA) and rosmarinic acid (RA)) and triterpenoids (e.g., oleic acid (OA) and ursolic acid (UA)), which have been reported to possess anti-cancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities, induce neural regeneration, and improve metabolic disorders [

11,

17,

18]. However, their effects on hiPSCs have not been reported.

In the present study, we examine the cytotoxic effects of an ethanol extract of PS (EPS) towards undifferentiated hiPSCs and their differentiated counterparts. We also characterize the role of p53 in the EPS-induced apoptosis of hiPSCs using p53 wild-type (WT) and p53 knock out (KO) hiPSCs and identify the underlying apoptotic mechanism of EPS in detail.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Both p53WT hiPSCs and p53KO hiPSCs were established and characterized as previously reported [

19]. p53WT hiPSCs and p53KO hiPSCs were maintained with mitomycin C-treated STO feeder cells (mouse embryo fibroblasts, CRL-1503) purchased from American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) or on the plates coated with hESC-qualified Matrigel matrix (#354277, Corning, Bedford, MA, USA)) in mTeSR1 medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). For passaging, the iPSCs were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) and then gently detached with ReLeSR (Stem Cell Technologies). STO feeder cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 1% non-essential amino acid (NEAA, Gibco), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME, Gibco), and 100 Units/mL penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin (#15140, Gibco). Human dermal fibroblasts (hDF, CRL-2429; ATCC) were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS.

2.2. Differentiation of hiPSCs into Embryonic Bodies (EBs) and General Differentiation of hiPSCs

To form embryonic bodies (EBs) with uniform size from hiPSCs, AggreWell800 6-well plates (Stem Cell Technologies) were used. To prevent cell adhesion and promote efficient EBs formation, plates were pre-treated with anti-adherence rinsing solution (Stem Cell Technologies) and then centrifuged at 1300× g for 5 min to remove all bubbles. After washing the wells, hiPSCs suspended in AggreWellEB formation medium (#5893, Stem Cell Technologies) were added to wells, and plates were centrifuged at 100× g for 3 min to capture cells in the microwells. Plates were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and 95% humidity and media were changed every 2 days. After 7 days, EBs were harvested using a 37-µm reversible strainer and used in subsequent experiments. EBs were identified by a decrease in pluripotent markers, including OCT4, NANOG, and DNMT3B, and an increase in three germ layer markers, including SOX1, GATA4, and T, compared to parent iPSCs. General differentiation of p53WT hiPSCs was induced by culturing cells on Matrigel-coated culture plates with DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% NEAA, 0.1 mM β-ME, and 100 Units/mL penicillin/100 μg/mL streptomycin for 10 days. Differentiation was characterized by a decrease of pluripotent markers OCT4, NANOG, and DNMT3B compared to parent iPSCs and abbreviated as iPSC-Diff.

2.3. Differentiation of hiPSCs to Hepatocytes Via Definitive Endoderm (DE)

hiPSCs were subjected to differentiate into definitive endoderm (DE) using the Cellartis DE Differentiation Kit with DEF-CS Culture System (cat. no. Y30035, TaKaRa Bio Europe AB, Sweden), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Prior to DE differentiation, hiPSCs were upscaled by passaging 5 times to adapt cells to the Cellartis DEF-CS Culture System. On day 7 of DE differentiation, the cells were enzymatically detached by TrypLE Select (Stem Cell Technologies) and guided to differentiate into hepatocytes using the Cellartis iPS Cell to Hepatocyte Differentiation System (cat. no. Y30055, TaKaRa Bio Europe AB), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. On days 9 and 11 of differentiation, media were changed using hepatocyte progenitor medium. On days 14 and 16, hepatocyte maturation medium was used. On day 18 and onwards, medium changes were performed every two days using hepatocyte maintenance medium. Differentiation was confirmed by the increase in hepatocyte markers, including cytochrome P450 34A (CYP34A), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and albumin, and by a decrease in Oct4 expression.

2.4. Reagents and Antibodies

N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and z-VAD-fmk were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Caffeic acid (CA), rosmarinic acid (RA), oleic acid (OA), ursolic acid (UA), propidium iodide (PI), Ribonuclease A (RNase A) from bovine pancreas, 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), and Triton X-100 were all obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against p27 (#3688), cyclin B (#4135), cyclin D1 (#2926), Bcl-xL (#2764), Bax (#2772), PARP (#9542), cleaved caspase-3 (#9664), cleaved caspase-9 (#9505), p53 (#48818), NOXA (#14766), MDM2 (#86934), ATM (#2873), p-ATM (#5883), H2AX (#2595), and p-H2AX (#2577)) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-PUMA (sc-374223) and anti-actin (sc-47778) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (#7074) and anti-mouse IgG (#7076) antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology.

2.5. Preparation of EPS

Lyophilized powder prepared from an ethanol extract of EPS was purchased from KOC Biotech (KOC201601-044, Daejeon, Korea). For experiments, EPS powder (50 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma Chemical Co.), filtered through a 0.22-µm disk filter, and stored at −20 °C.

2.6. Cell Viability Assay in Two-Dimensional (2D) and Three-Dimensional (3D) Cell Culture

To determine the effect of EPS on the cell viability in 2D monolayer culture, cells including p53WT hiPSCs, p53KO hiPSCs, iPSC-Diff, hDF, and hepatocytes were seeded into 12-well culture plates (Corning, Corning, NY, USA), allowed to adhere completely, and then treated with indicated concentrations of EPS. After 24 h, cell viability was measured using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a SpectraMax3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). For 3D cell culture, spheroids were formed in 96-well ultra-low attachment (ULA) round-bottomed plates (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea). After seeding the cell suspension in 96-well ULA plates, the plates were centrifuged at 200× g for 3 min, and then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity. EPS was treated during suspension (co-treatment) or after confirming spheroid formation (post-treatment) and multicellular spheroids were evaluated based on their size and shape using an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Cell Cycle Analysis

p53WT hiPSCs treated with 50 µg/mL EPS for 3, 6, 12, and 18 h were harvested, washed twice with D-PBS, and then fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol at −20 °C overnight. After washing fixed cells three times with D-PBS, intracellular DNA was labeled with 0.5 mL of cold PI solution (50 µg/mL PI, 50 µg/mL RNase A, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100 in D-PBS) in the dark at 4 °C for 30 min. Cell cycle distribution was analyzed using an LSRFortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR, USA).

2.8. Apoptosis Analysis

p53WT and p53KO hiPSCs were treated with 25 and 50 µg/mL EPS for 24 h, harvested, washed twice with cold D-PBS, and then stained with FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After labeling with annexin V-FITC and PI, cells were analyzed using an LSRFortessa X-20 and FlowJo software.

2.9. Caspase Activity Assay

p53WT hiPSCs treated with 25 and 50 µg/mL EPS for 24 h were measured for caspase-3 and -9 activities using caspase colorimetric assay kits (#K106and #K119; BioVision, Mountain View, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, EPS-treated cells were lysed using cell lysis buffer and determined for protein concentrations using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA). After adding 50 µL 2× reaction buffer to each sample (50 µg protein per 50 µL cell lysis buffer), 5 μL of substrates for caspase-3 (DEVD-pNA) or caspase-9 (LEHD-pNA) were added and incubated at 37 °C for 1–2 h. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm using the SpectraMax3 microplate reader.

2.10. Analysis of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Level

p53WT and p53KO hiPSCs were treated with 50 µg/mL EPS for 6 h and then incubated with peroxidase-sensitive fluorescence dye DCF-DA (5 µM) for 30 min. Cells were harvested and suspended in D-PBS, and then intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels were immediately measured using an LSRFortessa X-20 and analyzed using FlowJo software.

2.11. Detection of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP)

The alteration of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was detected using membrane-permeable lipophilic cationic fluorochrome JC-1 (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes). p53WT and p53KO hiPSCs grown on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (SPL Life Sciences) were treated with 25 and 50 µg/mL EPS for 6 h and then incubated with JC-1 (5 µg/mL) at 37 °C for 10 min in the dark. After washing with mTeSR1 medium, cells were observed under an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope. For FACS analysis, EPS-treated p53WT and p53KO hiPSCs were collected, resuspended in pre-warmed JC-1 working solution containing 5 µg/mL JC-1, and then incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in the dark. After washing with D-PBS, cells were immediately analyzed using an LSRFortessa X-20 and FlowJo software.

2.12. Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared with M-PER mammalian protein extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific) and the protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of cell lysates (20 µg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted using specific primary antibodies (diluted 1:1000) and HRP-linked secondary antibodies (diluted 1:4000). The protein levels were visualized by a Clarity Western ECL substrate (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and an ImageQuant LAS 4000 Mini chemiluminoscence detection system (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

2.13. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total cellular RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg RNA using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis System for RT–PCR (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was diluted to a constant concentration and qPCR was performed using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and a QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR System (PE Applied Biosystems). PCR conditions were as follows: 40 cycles of DNA denaturation (95 °C for 5 s), DNA annealing (55–60 °C for 30 s), and polymerization (72 °C for 30 s). The average cycle threshold (Ct) value was obtained from triplicate reactions and normalized to that of the GAPDH gene.

2.14. Immunofluorescence Analysis of γ-H2AX Foci Formation

iPSC-Diff grown on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes were treated with EPS or doxorubicin for 24 h. After being washed three times with cold D-PBS, cells were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma Chemical Co.) for 30 min at room temperature (RT), permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in D-PBS for 30 min at RT, and blocked with 3% BSA in D-PBS for 1 h at RT. After washing three times with cold D-PBS, cells were stained with anti-p-H2AX antibody (diluted 1:1000 in blocking buffer) overnight at 4 °C, followed by Alexa Fluor 594 chick anti-rabbit IgG antibody (diluted 1:1000) for 3 h at RT. After staining nuclei with DAPI, γ-H2AX foci were observed under an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescence microscope.

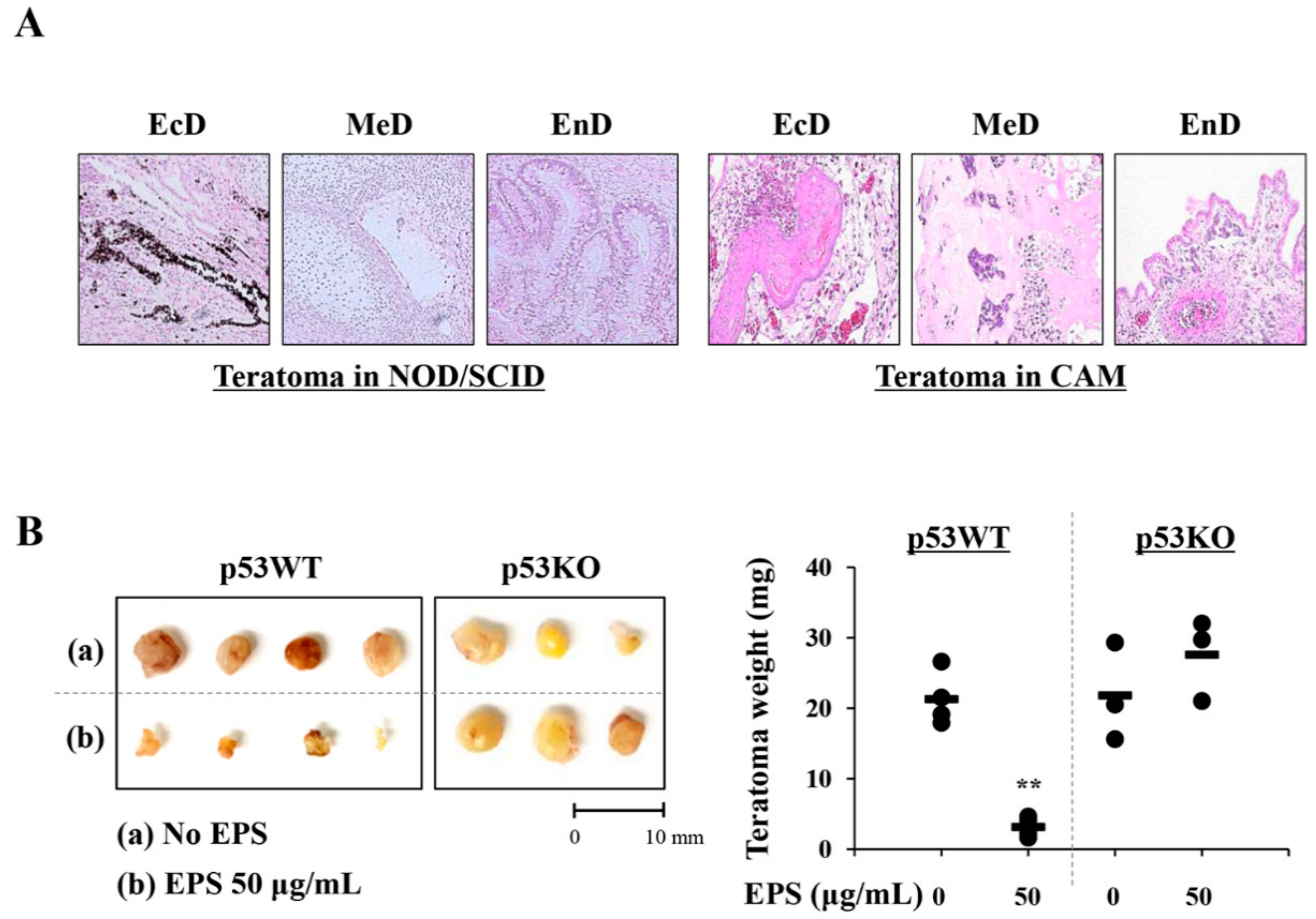

2.15. In Ovo Teratoma Formation and Hematoxylin–Eosin (H–E) Staining

Fertilized brown Leghorn eggs were obtained from Pulmuone Co., Ltd. (Seoul, Korea) and incubated in an egg incubator at 37 °C with 65% humidity (MX-190 CD; R-COM, Gimhae, Korea). The starting day was set as embryonic development (ED) day 0. On ED day 3, 7 mL albumin was carefully removed using a syringe and a round window was created at the blunt end of the egg. After covering these windows, eggs were further incubated. On ED day 10, iPSCs (1 × 106/egg) pre-treated with or without 50 µg/mL of EPS for 24 h were collected, mixed with cold Matrigel (50 µL), and then loaded on the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). On ED day 18, teratomas on CAMs were excised and weighed. For histological analysis, teratomas were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin using an automated tissue processor (Shandon Citadel 2000; Thermo Scientific). After the preparation of sections to 3–4 µm in thickness using an automated microtome (RM2255; Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany), they were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H–E) for the analysis of three different embryonic germ layers under a light microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). To generate in vivo teratomas, iPSCs (1 × 106/mouse) were harvested, mixed with cold Matrigel (50 µL), and then subcutaneously injected into the five-week-old male NOD.CB17-PrkdcSCID/J mice (OrientBio Inc., Seongnam, Korea). After ten weeks, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and xenograft were removed, fixed, and then subjected to H–E staining. The animal experiment was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (KIOM, Daejeon, Korea) with reference number #18-044 and carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of KIOM. During the experiment, all mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions (12 h/12 h light/dark cycle, 22 ± 1 °C, 55 ± 5% humidity) and observed daily.

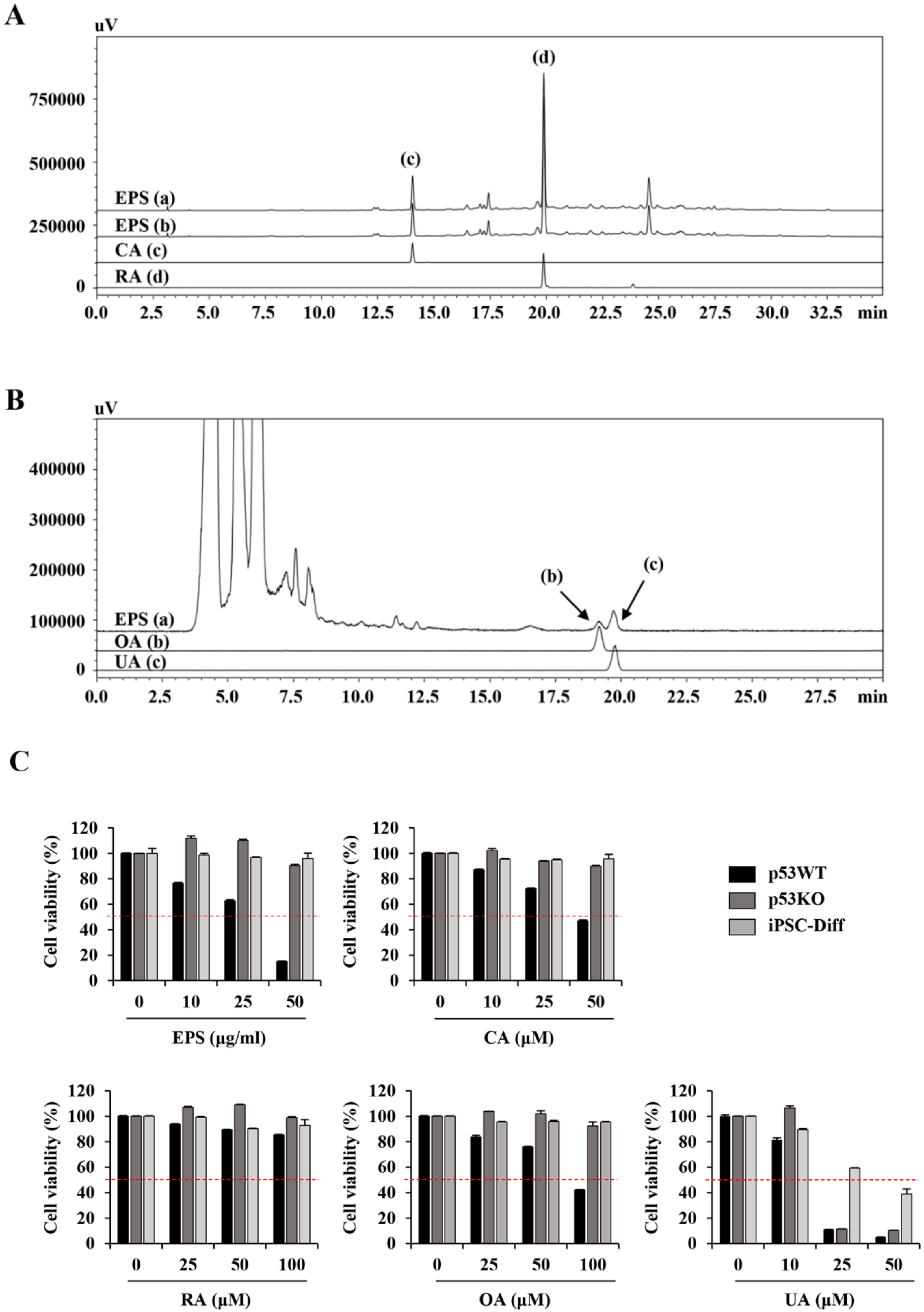

2.16. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis

Chromatic graphic analysis of EPS was performed using a Prominence LC-20A system (Shimadzu, Milan, Italy) equipped with an LC-20AT pump, SIL-20A auto-sampler, photodiode array (PDA) detector (SPD-M20A), and evaporative light scattering detector (ELSD; ELSD-LTII). Separation of two phenylpropanoids compounds, CA and RA, was performed with a Gemini C18 column (5 µm particle size, 250 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex Co., Torrance, CA, USA) at 40 °C, and the injection volume was 10 µL. Gradient elution was carried out using solvent A (0.1% (v/v) formic acid in distilled water) and solvent B (0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile); the gradient flow was as follows: 0–30 min with 5%–60% B, 30–40 min with 60%–100% B, 40–45 min with 100% B, and 45–50 min with 100%–5% B. The flow rate was 1 mL/min and chromatograms were detected at 325 and 330 nm. Two triterpenoids, OA and UA, were analyzed using the HPLC–ELSD system and the analytical conditions were as follows: column, Gemini C18 column (5 µm particle size, 250 × 4.6 mm); drift tube temperature, 60 °C; nitrogen pressure, 360 kPa, column oven temperature, room temperature; flow rate, 0.5 mL/min; injection volume, 10 µL, respectively. The mobile phase consisted of distilled water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both 1.0% (v/v) acetic acid and flowed by isocratic elution (A:B = 1:9). EPS powder (10 mg) was dissolved in 70% methanol (2 mL), sonicated for 60 min, filtered through 0.2 µm membrane filter, and then used for analysis.

2.17. Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance between two groups was analyzed with unpaired Student’s t-test. Treatment efficiency was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s test. All variables were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 Software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and a value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

4. Discussion

iPSCs, which can be obtained by reprogramming somatic cells, display similarities to embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in terms of morphological features, indefinite in vitro self-renewal, differentiation capacity into all cell types of the body, and genomic/epigenomic states [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Thus, iPSCs could replace ESCs and overcome the ethical concerns regarding the use of embryos in research and clinics. The iPSCs serve as a highly valuable cell source for cell-based regenerative medicine, including in vitro disease modeling, drug screening, toxicity prediction, and cell transplantation [

2,

3,

4]. Importantly, patient-specific iPSC lines generated from mature somatic cells of patients eliminate the risk of immune incompatibility between the donor and recipient, providing a new way to treat injuries and degenerative diseases, including neurodegenerative, cardiac, and retinal diseases, as well as muscle dystrophies, via a personalized medicine approach [

2,

32]. However, there are some limitations to overcome in the development of safe and efficient iPSC-based cell therapy products (CTPs). In vitro differentiation of iPSCs is asynchronous and incomplete, so iPSC-derived CTPs may contain undifferentiated cells in addition to the cells of interest. As these residual undifferentiated cells in CPTs are tumorigenic and can form teratomas at ectopic sites after in vivo transplantation, complete differentiation or selective elimination of residual undifferentiated cells in CTPs prior to transplantation is critical for clinical application [

5,

6]. Several methods for selective removal of undifferentiated iPSCs from a population of differentiated CTPs have been reported, such as modification of cell culture conditions, use of hiPSCs-specific sorting antibodies and chemical inhibitors, and introduction of suicide genes into hiPSCs [

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, none of these approaches are clinically applicable for regenerative therapy because of concerns regarding specificity, safety, and cost.

Considering the significant similarity in the growth rates of PSCs and cancer cells, the effects of different types of cytostatic drugs (e.g., mitomycin C, etoposide, vinblastine, and cycloheximide) on undifferentiated and differentiating PSCs have been investigated [

33,

34]. The results showed that these cytostatic drugs induced both anti-proliferative and acute cytotoxic effects in undifferentiated PSCs and teratocarcinoma cells, while they were less effective for differentiating ESCs and differentiated fibroblasts, indicating that these cytostatics and their analogs could be drug candidates for selective elimination of residual undifferentiated PSCs in a population of differentiating cells. In addition, the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) agonist, metformin, which specifically disrupts the cancer stem cell compartment in multiple cancers, limited the tumorigenicity of teratoma-initiating iPSCs without interfering with their pluripotency [

35]. Small molecules such as PluriSin#1 (an inhibitor of stearoyl-CoA desaturase), quercetin and YM155 (inhibitors of survivin), dinaciclib (a CDK inhibitor), and cardiac glycosides have been shown to induce selective cell death of undifferentiated iPSCs and efficiently prevent teratoma formation [

9,

36,

37]. However, all of these molecules have been investigated only in preclinical studies, and have not yet been approved for clinical use.

Many herbal medicines have been shown to be highly effective and safe for the control of malignant cancer cells [

38,

39]. Therefore, we screened herbal extracts with anti-cancer efficacy for the selective elimination of undifferentiated hiPSCs, but not differentiated cells (e.g., mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)). Extracts showing a difference in IC

50 between undifferentiated iPSCs and MSCs of more than 50-fold were identified, and EPS was used in this study. EPS has long been an important ingredient in traditional chinese medicine for the treatment of several cancers, and recent studies showed that it promoted apoptosis of cancer cells and reduced metastatic potential via effects on the migration and angiogenesis of cancer cells [

16,

40,

41].

We also found that EPS inhibited the growth, and induced apoptosis, of undifferentiated hiPSCs by inducing G

2/M cell cycle arrest, loss of MMP, activation of caspases, and an increase in the Bax to Bcl-xL ratio (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), as also observed in EPS-induced apoptosis of cancer cells, including HT-29 human colon carcinoma cells, A549 human lung cancer cells, and MCF-5 human breast carcinoma cells. We also found that EPS-induced apoptosis in hiPSCs was accompanied by p53 accumulation and an increase of its downstream target genes, such as

PUMA,

NOXA, MDM2, and

p21 (

Figure 5). In human ESCs, it has been reported that reducing p53 expression using siRNA led to lower rates of spontaneous apoptosis and higher rates of cell survival. Consistent with these observations, in p53KO hiPSCs, EPS had no effects on cell proliferation or apoptosis, confirming the critical role of p53 accumulation for initiating EPS-induced cell death (

Figure 6). Moreover, EPS did not show any toxicity towards differentiated cells in terms of cell viability or genome stability (

Figure 7). For clinical use of EPS, the genetic stability of iPSCs-derived differentiated cells is crucial. During cancer therapy, gamma irradiation and chemotherapeutics are known to exert harmful effects on normal cells, including stem cells, as well as cancer cells [

42]. In the present study, we observed that doxorubicin at 0.25 and 0.5 µM suppressed cell proliferation of differentiated cells by approximately 20% and 50%, respectively, and remarkably induced phosphorylation of ATM and H2AX; meanwhile, EPS was not genotoxic to differentiated cells at the concentrations used in this study. Moreover, transplantation of EPS-treated cells resulted in the complete prevention of teratoma formation (

Figure 8).

It has recently been reported that during hepatocyte differentiation, treatment with YM155, which is known to induce selective and complete cell death of undifferentiated hiPSCs, improved the quantity and quality of induced hepatocytes and consequently eliminated the possibility of teratoma formation [

43]. Based on these observations, and our present findings, differentiation protocols can be devised to obtain safe cell sources with no risk of teratoma formation. This protocol involves exposing hiPSC-derived mixed populations to EPS in vitro, and washing them thoroughly, followed by further differentiation. Alternatively, EPS can be added during differentiation.

This is the first study to demonstrate the efficacy of EPS for developing stem cells and to elucidate the underlying mechanism. Our data strongly support the beneficial effect of EPS for the establishment of cell sources for stem cell therapy in terms of efficacy, safety, and cost. Based on this work, we are currently investigating whether EPS treatment can increase the quantity and quality of hiPSC-derived differentiation products and completely eliminate the risk of teratoma formation.