Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Changes of employment status in the context of COVID-19 would be appraised as both stressful and uncontrollable.

- Stressor appraisals would mediate the relations between change of employment status and greater use of particular coping strategies, including problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidant coping.

- Changes of employment status, appraisals of the COVID-19 situation, and coping strategies would be predictive of positive and negative affect.

- Negative affect, but not positive affect, would be associated with eating to cope, as well as unhealthy snacking behaviors, i.e., eating more salty and sweet processed snacks rather than wholesome/unprocessed foods.

- Eating to cope would mediate the relations between negative mood and snacking behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographics

2.2.2. COVID-19 Experiences

2.2.3. Food and Beverage Consumption

2.2.4. Mood

2.2.5. Stress Appraisals

2.2.6. Coping Strategies

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. What Was the Variation of COVID Experiences, and the Associations between Such Experiences, Demographic Features of the Sample, and the Model Variables of Interest?

3.1.1. COVID-19 Experiences

3.1.2. Relations between Change of Employment Status Due to COVID-19 and Demographic Features

3.1.3. Model Variables

3.1.4. Summary

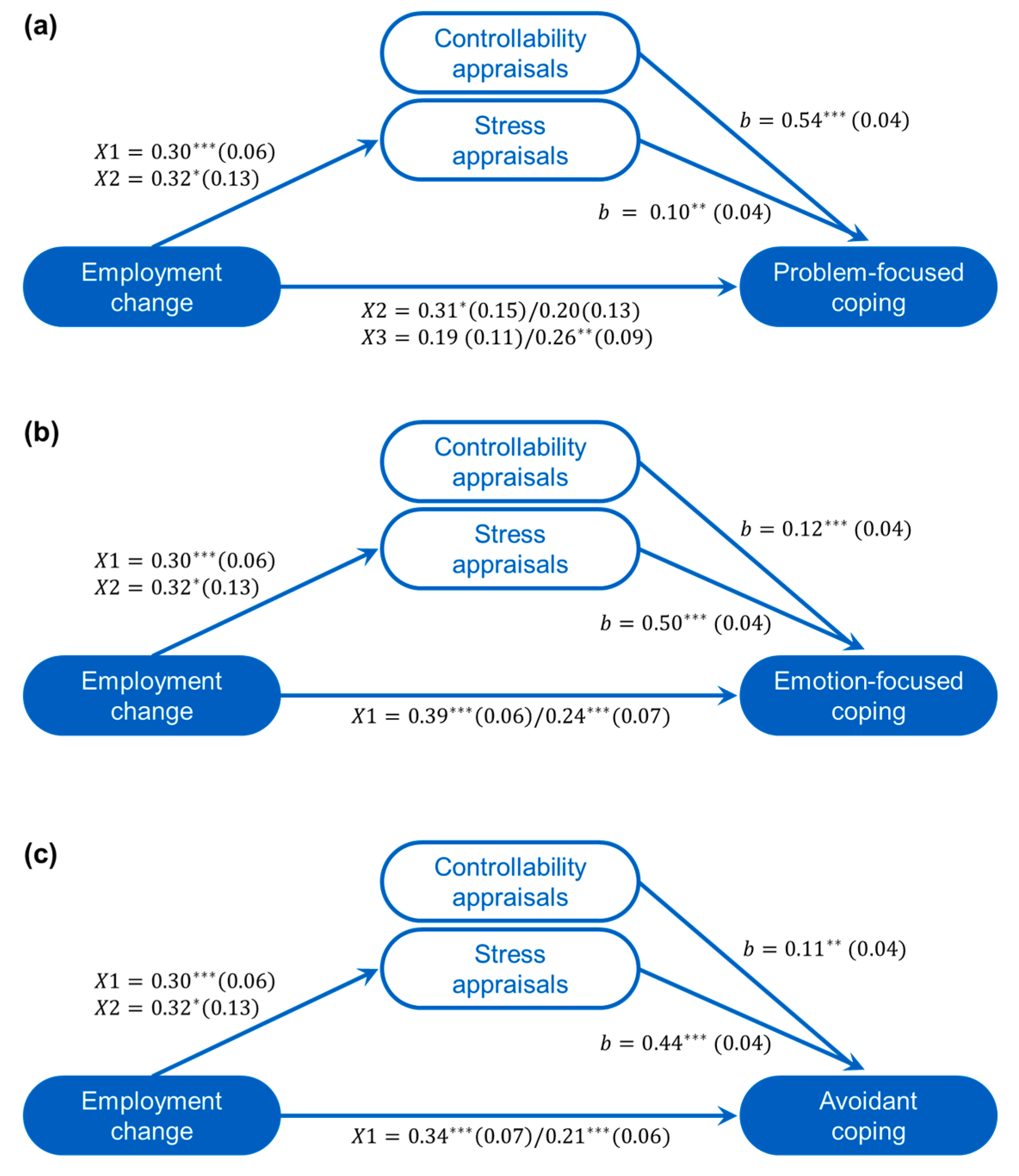

3.2. Were Changes in Employment Status as a Result of COVID-19 Associated with Stressor Appraisals and General Coping Strategies?

Summary

3.3. Were Stressor Appraisals and Coping Strategies Related to Current Affective States?

3.3.1. Positive Affect

3.3.2. Negative Affect

3.3.3. Summary

3.4. Were Snacking Behaviors Associated with Stress-Related Affective States and Eating to with Stressors?

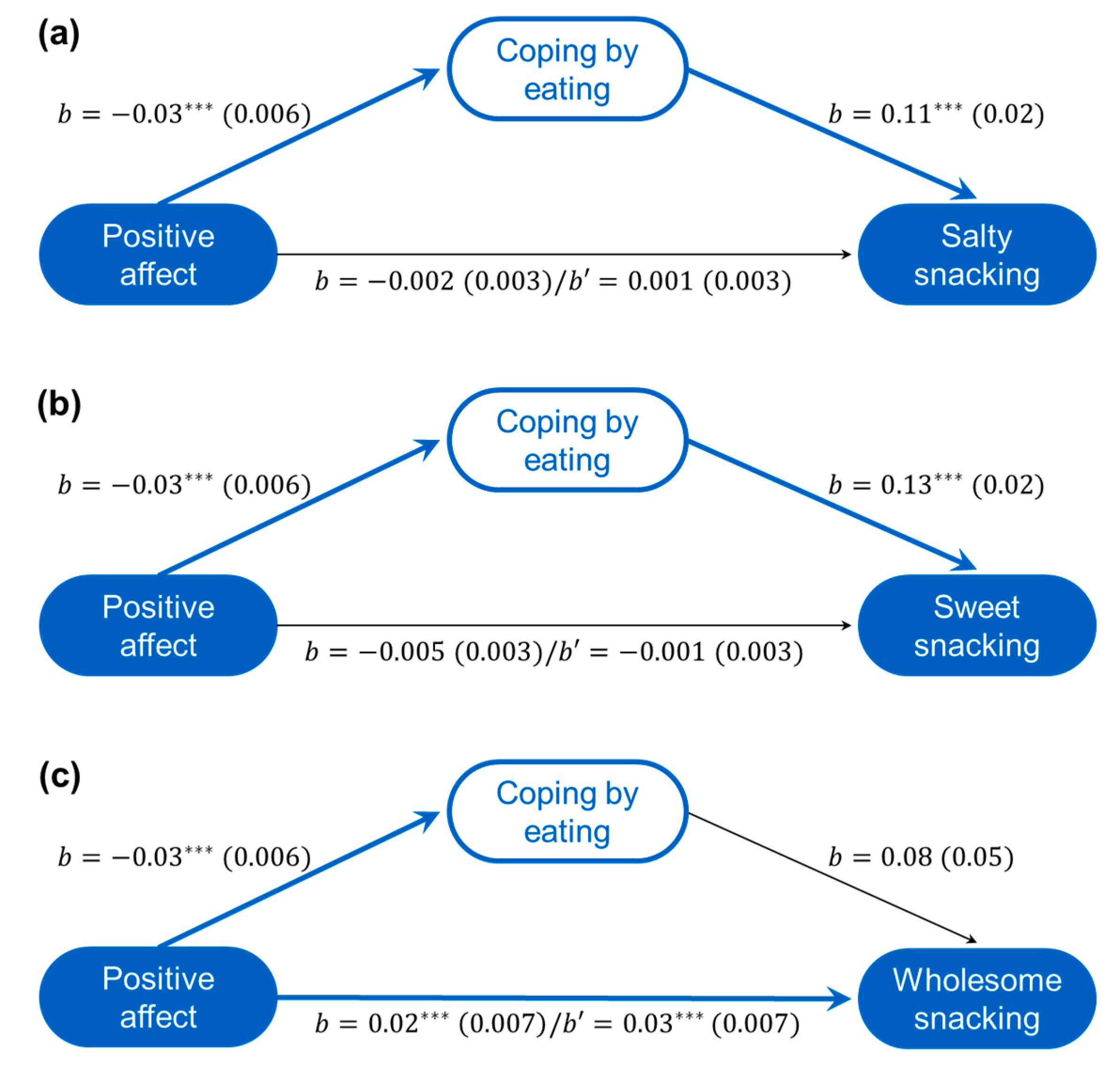

3.4.1. Eating Choices Associated with Positive Affect

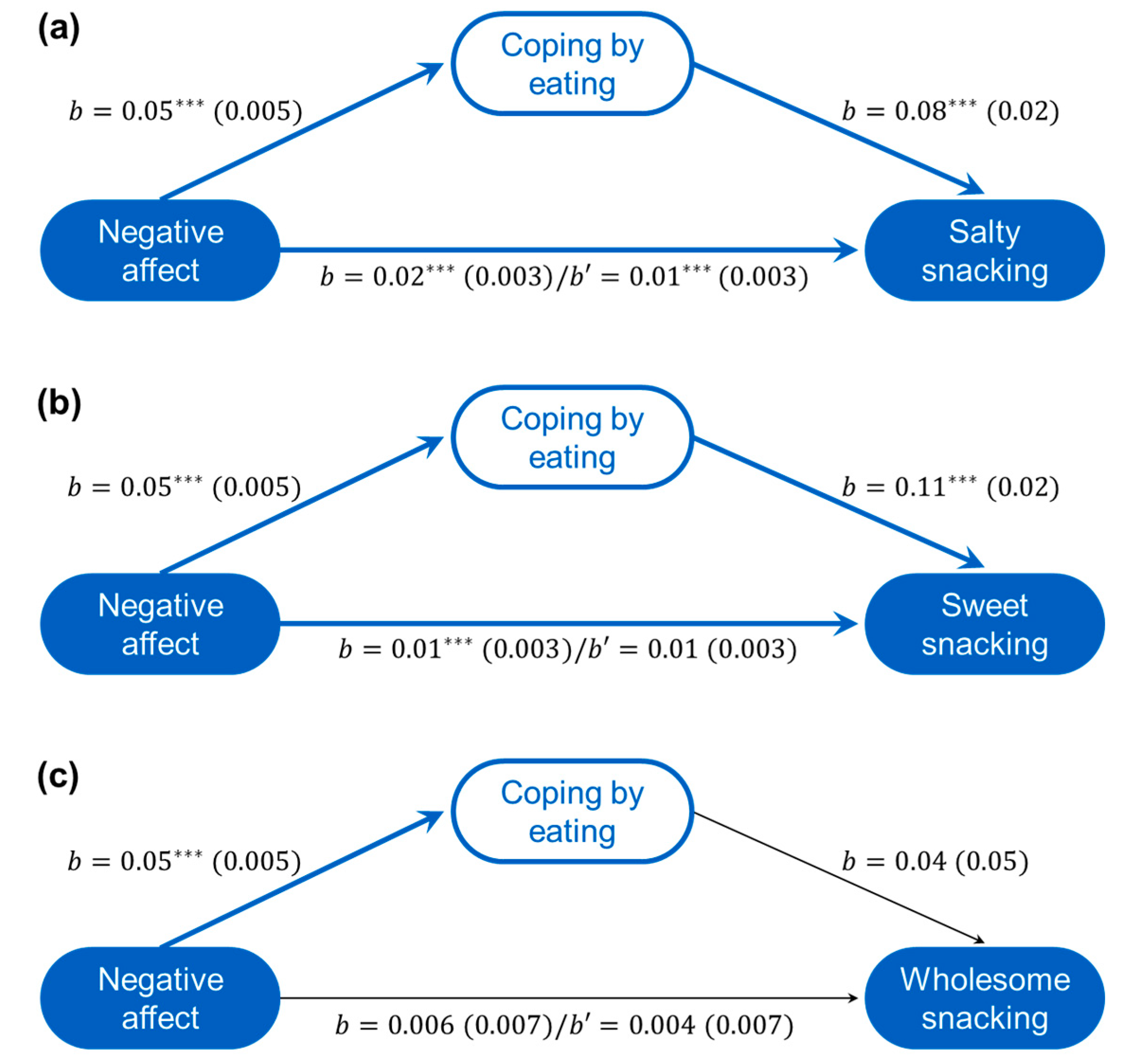

3.4.2. Eating Choices Associated with Negative Affect

3.4.3. Summary

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey, April 2020. In Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 11-001-X: 2020; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. The Employment Situation—May 2020. In U.S. Department of Labor USDL-20-1140: 2020; Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, N.; Sadowski, A.; Laila, A.; Hruska, V.; Nixon, M.; Ma, D.W.L.; Haines, J.; On Behalf of the Guelph Family Health Study. The Impact of COVID-19 on Health Behavior, Stress, Financial and Food Security among Middle to High Income Canadian Families with Young Children. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M.; Lee, J.; Fitzgerald, H.N.; Oosterhoff, B.; Sevi, B.; Shook, N.J. Job Insecurity and Financial Concern during the COVID-19 Pandemic are Associated with Worse Mental Health. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 62, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almandoz, J.P.; Xie, L.; Schellinger, J.N.; Mathew, M.S.; Gazda, C.; Ofori, A.; Kukreja, S.; Messiah, S.E. Impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on weight-related behaviours among patients with obesity. Clin. Obes. 2020, 10, e12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Cinelli, G.; Bigioni, G.; Soldati, L.; Attina, A.; Bianco, F.F.; Caparello, G.; Camodeca, V.; Carrano, E.; et al. Psychological Aspects and Eating Habits during COVID-19 Home Confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazza, C.; Ricci, E.; Biondi, S.; Colasanti, M.; Ferracuti, S.; Napoli, C.; Roma, P. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardel, M.I.; Manasse, S.; Krukowski, R.A.; Ross, K.; Shakour, R.; Miller, D.R.; Lemas, D.J.; Hong, Y.R. COVID-19 Impacts Mental Health Outcomes and Ability/Desire to Participate in Research Among Current Research Participants. Obesity 2020, 28, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, E.W.; Beyl, R.A.; Fearnbach, S.N.; Altazan, A.D.; Martin, C.K.; Redman, L.M. The impact of COVID-19 stay-at-home orders on health behaviors in adults. Obesity 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.P.; He, Y.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Ding, L.; Ayanian, J.Z. Psychosocial stress and change in weight among US adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 170, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zachary, Z.; Brianna, F.; Brianna, L.; Garrett, P.; Jade, W.; Alyssa, D.; Mikayla, K. Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 14, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics Canada. Health Fact Sheets: Overweight and Obese Adults, 2018. In Statistics Canada Catalogue No. 82-625-X: 2019; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, C.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Fryar, C.D.; Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity among Adults: United States, 2017–2018; NCHS Data Brief, No. 360; National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2020.

- Barquera, S.; Campos-Nonato, I.; Hernandez-Barrera, L.; Flores, M.; Durazo-Arvizu, R.; Kanter, R.; Rivera, J.A. Obesity and central adiposity in Mexican adults: Results from the Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey 2006. Salud Publica Mex. 2009, 51 (Suppl. 4), S595–S603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemmensen, C.; Petersen, M.B.; Sørensen, T.I.A. Will the COVID-19 pandemic worsen the obesity epidemic? Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Wurth, R.; Kamilaris, C.D.C.; Eisenhofer, G.; Barrera, F.J.; Hajdenberg, M.; Tonleu, J.; Hall, J.E.; Schiffrin, E.L.; Porter, F.; et al. Endocrine Conditions and COVID-19. Horm. Metab. Res. 2020, 52, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peçanha, T.; Goessler, K.F.; Roschel, H.; Gualano, B. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1441–H1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Marshall, K.E.; Dowling, N.F.; Paz-Bailey, G.; Twentyman, E.R.; Peacock, G.; Greenlund, K.J. Estimated County-Level Prevalence of Selected Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Increased Risk for Severe COVID-19 Illness—United States, 2018. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Kim, L.; Whitaker, M.; O’Halloran, A.; Cummings, C.; Holstein, R.; Prill, M.; Chai, S.J.; Kirley, P.D.; Alden, N.B.; et al. Hospitalization Rates and Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized with Laboratory-Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019—COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonnet, A.; Chetboun, M.; Poissy, J.; Raverdy, V.; Noulette, J.; Duhamel, A.; Labreuche, J.; Mathieu, D.; Pattou, F.; Jourdain, M.; et al. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity 2020, 28, 1195–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lighter, J.; Phillips, M.; Hochman, S.; Sterling, S.; Johnson, D.; Francois, F.; Stachel, A. Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid-19 hospital admission. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 896–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butler, M.J.; Barrientos, R.M. The impact of nutrition on COVID-19 susceptibility and long-term consequences. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 53–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, G.; Wardle, J. Perceived effects of stress on food choice. Physiol. Behav. 1999, 66, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laugero, K.D.; Falcon, L.M.; Tucker, K.L. Relationship between perceived stress and dietary and activity patterns in older adults participating in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Appetite 2011, 56, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ozier, A.D.; Kendrick, O.W.; Knol, L.L.; Leeper, J.D.; Perko, M.; Burnham, J. The Eating and Appraisal Due to Emotions and Stress (EADES) Questionnaire: Development and validation. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnow, B.; Kenardy, J.; Agras, W.S. The Emotional Eating Scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1995, 18, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, N.J.; Huon, G.F. Negative affect and binge eating in overweight women. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.R.; Fisher, E.B., Jr. Emotional reactivity, emotional eating, and obesity: A naturalistic study. J. Behav. Med. 1983, 6, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Wansink, B.; Inman, J.J. The Influence of Incidental Affect on Consumers’ Food Intake. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorikhin, A.; Patrick, V.M. Positive Mood and Resistance to Temptation: The Interfering Influence of Elevated Arousal. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 698–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rolland, B.; Haesebaert, F.; Zante, E.; Benyamina, A.; Haesebaert, J.; Franck, N. Global Changes and Factors of Increase in Caloric/Salty Food Intake, Screen Use, and Substance Use During the Early COVID-19 Containment Phase in the General Population in France: Survey Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidor, A.; Rzymski, P. Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gornicka, M.; Drywien, M.E.; Zielinska, M.A.; Hamulka, J. Dietary and Lifestyle Changes During COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdowns among Polish Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey PLifeCOVID-19 Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; Knott-Torcal, C.; Matilla-Escalante, D.C.; Garcimartin, A.; Sampedro-Nunez, M.A.; Davalos, A.; Marazuela, M. COVID-19 Lockdown and Changes of the Dietary Pattern and Physical Activity Habits in a Cohort of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Perez, C.; Molina-Montes, E.; Verardo, V.; Artacho, R.; Garcia-Villanova, B.; Guerra-Hernandez, E.J.; Ruiz-Lopez, M.D. Changes in Dietary Behaviours during the COVID-19 Outbreak Confinement in the Spanish COVIDiet Study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynihan, A.B.; van Tilburg, W.A.; Igou, E.R.; Wisman, A.; Donnelly, A.E.; Mulcaire, J.B. Eaten up by boredom: Consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez-Espina, S.; Llosa, J.A.; Agullo-Tomas, E.; Rodriguez-Suarez, J.; Saiz-Villar, R.; Lahseras-Diez, H.F. Job Insecurity and Mental Health: The Moderating Role of Coping Strategies From a Gender Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarro-Abal, Y.; Climent-Rodriguez, J.A.; Lopez-Lopez, M.J.; Gomez-Salgado, J. Psychological Coping with Job Loss. Empirical Study to Contribute to the Development of Unemployed People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meltzer, H.; Bebbington, P.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; McManus, S.; Stansfeld, S. Job insecurity, socio-economic circumstances and depression. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stansfeld, S.; Candy, B. Psychosocial work environment and mental health--a meta-analytic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2006, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, M.; Hellgren, J.; Naswall, K. No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2002, 7, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Matheson, K.; Anisman, H. Systems of coping associated with dysphoria, anxiety and depressive illness: A multivariate profile perspective. Stress 2003, 6, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuhouser, M.L.; Lilley, S.; Lund, A.; Johnson, D.B. Development and validation of a beverage and snack questionnaire for use in evaluation of school nutrition policies. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, E.J.; Wong, P.T.P. The stress appraisal measure (SAM): A multidimensional approach to cognitive appraisal. Stress Med. 1990, 6, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V. Impacts of COVID-19: A research agenda to support people in their fight. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, A.W.; Bertrand, M.; Lin, F.; Rothstein, J.; Unrath, M. Measuring the Labor Market at the Onset of the COVID-19 Crisis; 0898-2937; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020.

- Lemieux, T.; Milligan, K.; Schirle, T.; Skuterud, M. Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Canadian Labour Market. Can. Public Policy 2020, 46, S55–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Costa Dias, M.; Joyce, R.; Xu, X. COVID-19 and Inequalities. Fisc. Stud. 2020, 41, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geliebter, A.; Aversa, A. Emotional eating in overweight, normal weight, and underweight individuals. Eat. Behav. 2003, 3, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, L.; Rosenblatt, Z. Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Employment: Distribution of Employment by Aggregate Sectors, by Sex. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54755 (accessed on 27 October 2020).

- United Food and Commercial Workers. By the Numbers: Canada’s Food Service Industry. Available online: http://www.ufcw.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=31416:by-the-numbers-canada-s-food-service-industry&catid=9830&Itemid=6&lang=en (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Invicibles, Y. Where Do Young Adults Work? Available online: https://www.issuelab.org/resources/21894/21894.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Kramer, A.; Kramer, K.Z. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 119, 103442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellgren, J.; Sverke, M.; Isaksson, K. A Two-dimensional Approach to Job Insecurity: Consequences for Employee Attitudes and Well-being. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, G.M.; Acton, G.J. The relationship between basic need satisfaction and emotional eating. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2001, 22, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Long, L.M.; Shih, C.H.; Ludy, M.J. A Humanities-Based Explanation for the Effects of Emotional Eating and Perceived Stress on Food Choice Motives during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, B.L.; Lissner, L. Dietary underreporting by obese individuals--is it specific or non-specific? BMJ 1995, 311, 986–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, S.E.; Shide, D.J.; Rolls, B.J. Changes in food intake in response to stress in men and women: Psychological factors. Appetite 1997, 28, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, D.A.; Loaiza, S.; Gonzalez, Z.; Pita, J.; Morales, J.; Pecora, D.; Wolf, A. Food selection changes under stress. Physiol. Behav. 2006, 87, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, J.J.; Scott, J.A.; Lean, M.E.J. Intentional mis-reporting of food consumption and its relationship with body mass index and psychological scores in women. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2004, 17, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snoek, H.M.; van Strien, T.; Janssens, J.M.; Engels, R.C. Restrained eating and BMI: A longitudinal study among adolescents. Health Psychol. 2008, 27, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zizza, C.; Siega-Riz, A.M.; Popkin, B.M. Significant increase in young adults’ snacking between 1977–1978 and 1994–1996 represents a cause for concern! Prev. Med. 2001, 32, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J.; Carter, H.; Cocking, C.; Ntontis, E.; Tekin Guven, S.; Amlot, R. Facilitating Collective Psychosocial Resilience in the Public in Emergencies: Twelve Recommendations Based on the Social Identity Approach. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Variable | Number of Participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 510 (75.0%) |

| Male | 155 (22.8%) |

| Other (e.g., transgender, non-binary) | 15 (2.2%) |

| Cultural affiliation | |

| White and/or Euro-Caucasian | 523 (76.9%) |

| Black and/or African | 29 (4.3%) |

| Asian (West, South, East, or Southeast) | 121 (17.8%) |

| Latin American and Caribbean | 29 (4.3%) |

| Indigenous | 12 (1.7%) |

| Other | 5 (0.7%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single, not seeing anyone | 211 (31.0%) |

| In a relationship | 146 (21.5%) |

| Cohabitating/Married | 288 (42.4%) |

| Separated/Divorced | 27 (4.0%) |

| Widowed | 8 (1.2%) |

| Household income | |

| Under $15,000 (1) 1 | 35 (5.1%) |

| $15,000–$29,999 (2) | 61 (9.0%) |

| $30,000–$44,999 (3) | 55 (8.1%) |

| $45,000–$59,999 (4) | 76 (11.2%) |

| $60,000–$74,999 (5) | 76 (11.2%) |

| $75,000–$89,999 (6) | 77 (11.3%) |

| $90,000–$104,999 (7) | 69 (10.1%) |

| $105,000 or more (8) | 228 (33.5%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed Part-time | 128 (18.8%) |

| Employed Full-time | 286 (42.1%) |

| Self-employed | 50 (7.4%) |

| Unemployed | 147 (21.6%) |

| Retired | 54 (7.9%) |

| Other | 15 (2.2%) |

| Location | |

| Canada | 559 (82.2%) |

| United States | 121 (17.8%) |

| Living arrangement | |

| Living alone | 95 (14.0%) |

| Living with others | 408 (60.0%) |

| Living with others and children | 156 (22.9%) |

| Living alone and children | 21 (3.1%) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 94 (13.8%) |

| Post-secondary education | 584 (85.9%) |

| Other | 2 (0.3%) |

| No Change (n = 389) | More Hours (n = 34) | Reduced Hours (n = 97) | Laid Off (n = 160) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 1 | 40.48 (16.01) a | 38.23 (15.42) a,b | 34.46 (12.68) b | 29.09 (13.19) c |

| Income 1,2 | 5.77 (2.26) a | 6.35 (2.39) a | 5.01 (2.22) b | 5.29 (2.37) a,b |

| Gender 3 | ||||

| Female | 290 (56.9%) | 26 (5.3%) | 60 (11.8%) | 133 (26.1%) |

| Male | 93 (60.0%) | 6 (3.9%) | 34 (21.9%) | 22 (14.2%) |

| Education 3 | ||||

| High school or less | 37 (39.4%) | 7 (7.4%) | 7 (7.4%) | 43 (45.7%) |

| Some post-secondary | 350 (59.9%) | 27 (4.6%) | 90 (15.4%) | 117 (20.0%) |

| Living arrangement 3 | ||||

| Alone | 73 (76.8%) | 4 (4.2%) | 8 (8.4%) | 10 (10.5%) |

| With others | 205 (50.2%) | 21 (5.1%) | 59 (14.5%) | 123 (30.1%) |

| Others with children | 100 (64.1%) | 7 (4.5%) | 26 (16.7%) | 23 (14.7%) |

| Alone with children | 11 (52.4%) | 2 (9. 5%) | 4 (19.0%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| National location 3 | ||||

| Canada | 308 (55.1%) | 28 (5.0%) | 68 (12.2%) | 155 (27.7%) |

| United States | 81 (66.9%) | 6 (5.0%) | 29 (24.0%) | 5 (4.1%) |

| No Change (n = 389) | More Hours (n = 34) | Reduced Hours (n = 97) | Laid Off (n = 160) | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appraisals | |||||

| Stress | 2.61 (0.73) a | 2.69 (0.77) a | 2.97 (0.73) b | 3.05 (0.73) b | 0.070 *** |

| Controllability | 3.10 (0.74) | 3.00 (0.74) | 3.20 (0.63) | 3.04 (0.72) | 0.005 |

| Coping | |||||

| Problem-focused | 3.13 (0.82) a,b | 2.91 (0.84) a | 3.13 (0.78) a,b | 3.31 (0.83) b | 0.013 * |

| Emotion-focused | 2.22 (0.82) a | 2.56 (0.96) b | 2.62 (0.87) b | 2.66 (0.80) b | 0.057 *** |

| Avoidant | 2.57 (0.79) a | 2.74 (0.88) a,b | 2.94 (0.79) b | 3.03 (0.76) b | 0.065 *** |

| Eating | 2.52 (1.25) | 2.77 (1.33) | 2.87 (1.24) | 2.96 (1.24) | 0.024 *** |

| Affect | |||||

| Positive | 27.69 (8.44) | 28.21 (9.56) | 29.41 (8.21) | 26.16 (7.93) | 0.014 * |

| Negative | 18.22 (8.01) a | 22.09 (9.43) b | 21.01 (8.69) a,b | 23.01 (9.52) b | 0.056 *** |

| Snacking | |||||

| Salty | 1.68 (0.66) a | 1.88 (0.74) a,b | 2.03 (1.00) b | 1.78 (0.75) a,b | 0.026 *** |

| Sweet | 1.79 (0.66) | 1.86 (0.82) | 2.01 (0.78) | 1.90 (0.70) | 0.013 * |

| Wholesome | 3.67 (1.63) | 3.69 (1.53) | 3.49 (1.57) | 3.63 (1.53) | 0.002 |

| Positive Affect | Negative Affect | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | Beta | r | b | se | Beta | r | |

| Employment change | ||||||||

| No change vs. change | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.10 ** | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.14 | –0.05 | 0.23 *** |

| More hours vs. reduced/laid off | −0.36 | 0.42 | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.65 | 0.38 | −0.05 | 0.11 ** |

| Reduced hours vs. laid off | −1.44 | 0.44 | −0.11 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.05 | 0.11 ** |

| Appraisals | ||||||||

| Stress | −1.21 | 0.41 | −0.11 ** | −0.21 *** | 5.47 | 0.37 | 0.47 *** | 0.65 *** |

| Controllability | 4.22 | 0.42 | 0.36 *** | 0.49 *** | −0.59 | 0.38 | −0.05 | −0.10 * |

| Coping | ||||||||

| Problem-focused | 2.96 | 0.38 | 0.29 *** | 0.37 *** | −1.22 | 0.34 | −0.11 *** | 0.01 |

| Emotion-focused | −1.58 | 0.40 | −0.16 *** | −0.16 *** | 2.82 | 0.36 | 0.28 *** | 0.54 *** |

| Avoidant | −1.08 | 0.42 | −0.11 * | −0.12 ** | 1.26 | 0.38 | 0.12 *** | 0.45 *** |

| Coping by Eating | Snacking | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salty | Sweet | Wholesome | ||

| Appraisals | ||||

| Stressful | 0.33 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.01 |

| Controllable | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.13 *** |

| Coping | ||||

| Problem-focused | 0.07 | 0.004 | 0.04 | 0.24 *** |

| Emotion-focused | 0.31 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.09 * |

| Avoidant | 0.43 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.06 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chee, M.J.; Koziel Ly, N.K.; Anisman, H.; Matheson, K. Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123803

Chee MJ, Koziel Ly NK, Anisman H, Matheson K. Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020; 12(12):3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123803

Chicago/Turabian StyleChee, Melissa J., Nikita K. Koziel Ly, Hymie Anisman, and Kimberly Matheson. 2020. "Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19" Nutrients 12, no. 12: 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123803

APA StyleChee, M. J., Koziel Ly, N. K., Anisman, H., & Matheson, K. (2020). Piece of Cake: Coping with COVID-19. Nutrients, 12(12), 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12123803