Towards a Better Primary Healthcare in Europe: Shifts in Public Health Nutrition Policies

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

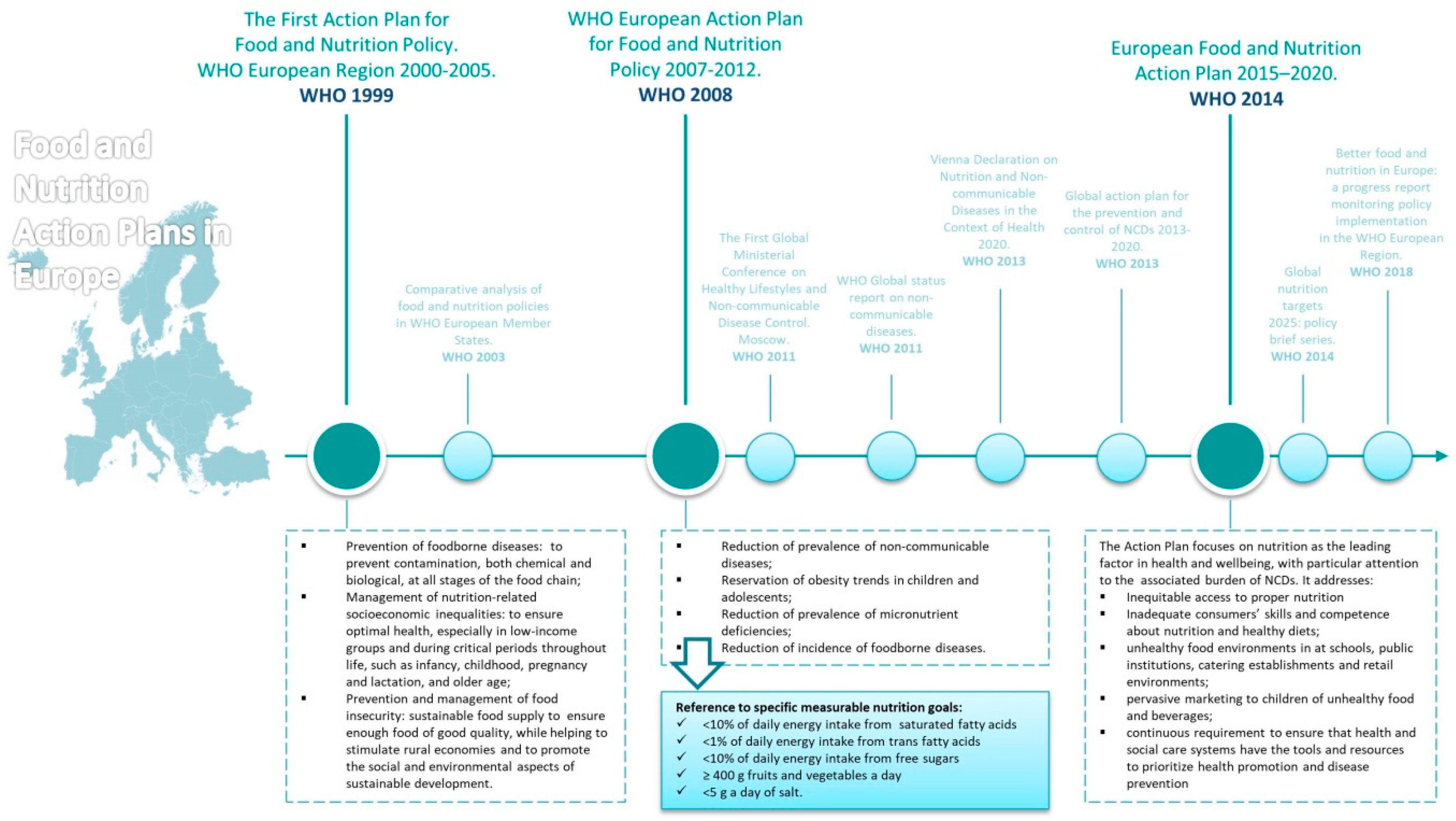

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe Better Food and Nutrition in Europe: A Progress Report Monitoring Policy Implementation in the WHO European Region; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases 2014; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R.J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A.; et al. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gakidou, E.; Afshin, A.; Abajobir, A.A.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.M.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdulle, A.M.; Abera, S.F.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1345–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, E.; Wilson, L.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Bhatnagar, P.; Leal, J.; Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Burns, R.; Rayner, M. Townsend N European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017; European Heart Network: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Breda, J.; Castro, L.S.N.; Whiting, S.; Williams, J.; Jewell, J.; Engesveen, K.; Wickramasinghe, K. Towards better nutrition in Europe: Evaluating progress and defining future directions. Food Policy 2020, 101887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrell, G.; Vandevijvere, S. Socio-economic inequalities in diet and body weight: Evidence, causes and intervention options. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 759–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. The First Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy. WHO European Region 2000–2005; Nutrition and Food Security Programme Division of Technical Support and Strategic Development; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe Comparative Analysis of Food and Nutrition Policies in WHO European Member States; Nutrition and Food Security Programme; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO European Action Plan for Food and Nutrition Policy 2007–2012; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Moscow Declaration: The First Global Ministerial Conference on Healthy Lifestyles and Noncommunicable Disease Control; WHO: Moscow, Russia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Disease; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional office for europe vienna declaration on nutrition and noncommunicable diseases in the context of health 2020. In Proceedings of the WHO Ministerial Conference on Nutrition and Noncommunicable Diseases in the Context of Health 2020, Vienna, Austria, 4–5 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020; World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Policy Brief Series; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission State of Health in the EU: Companion Report 2019; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2019.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panagiotakos, D.B.; Kouvari, M.; Souliotis, K. Towards a Better Primary Healthcare in Europe: Shifts in Public Health Nutrition Policies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113308

Panagiotakos DB, Kouvari M, Souliotis K. Towards a Better Primary Healthcare in Europe: Shifts in Public Health Nutrition Policies. Nutrients. 2020; 12(11):3308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113308

Chicago/Turabian StylePanagiotakos, Demosthenes B., Matina Kouvari, and Kyriakos Souliotis. 2020. "Towards a Better Primary Healthcare in Europe: Shifts in Public Health Nutrition Policies" Nutrients 12, no. 11: 3308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113308

APA StylePanagiotakos, D. B., Kouvari, M., & Souliotis, K. (2020). Towards a Better Primary Healthcare in Europe: Shifts in Public Health Nutrition Policies. Nutrients, 12(11), 3308. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113308