Designing an Effective Front-of-Package Warning Label for Food and Drinks High in Added Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat in Colombia: An Online Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Warning Development

2.3. Product Development

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Measures

2.6. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Single Product Assessment of Soda, Bread, and Cookies High in Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat

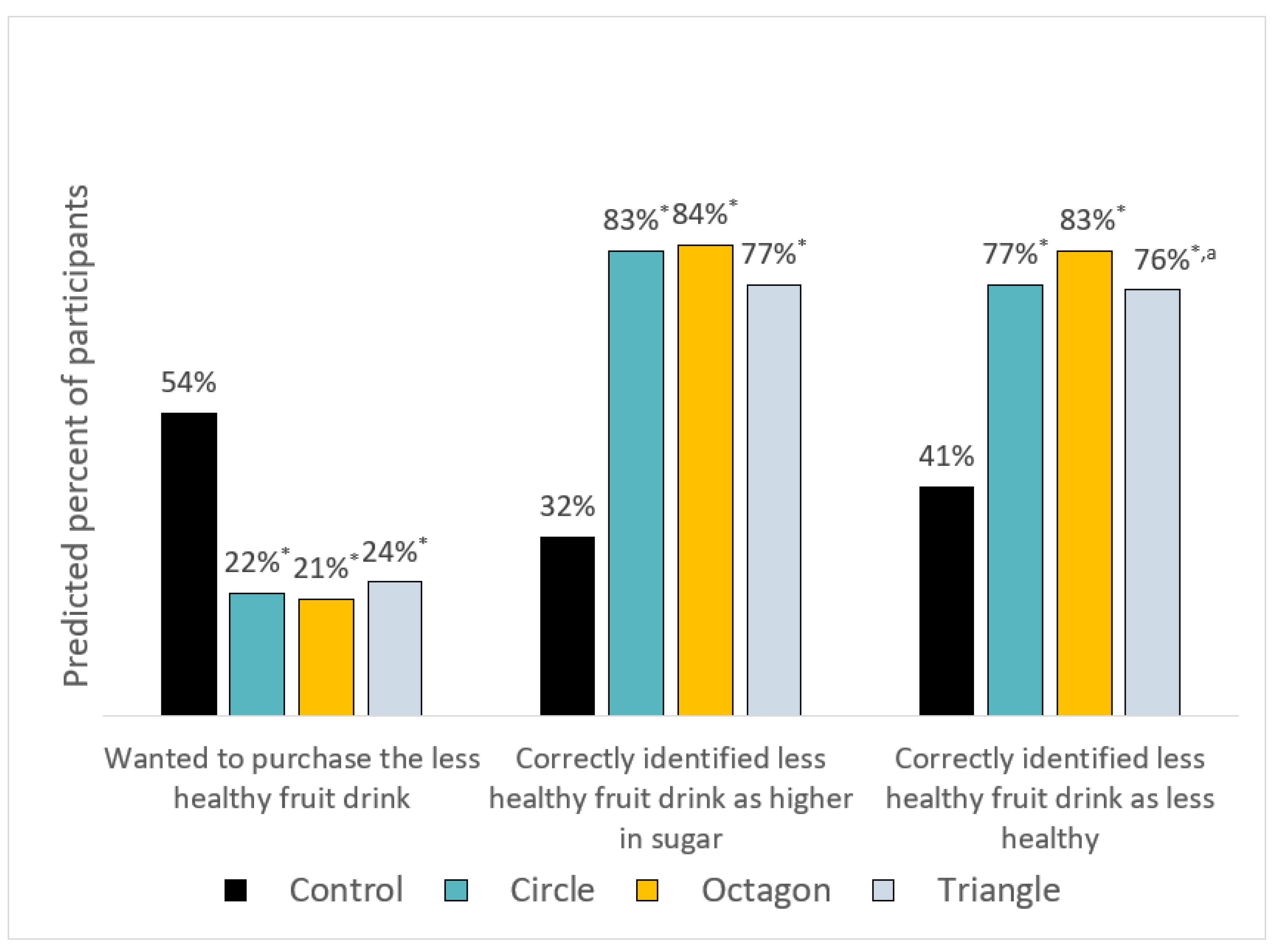

3.3. Choice Experiment between a Fruit Drink and Less-Healthy Fruit Drink

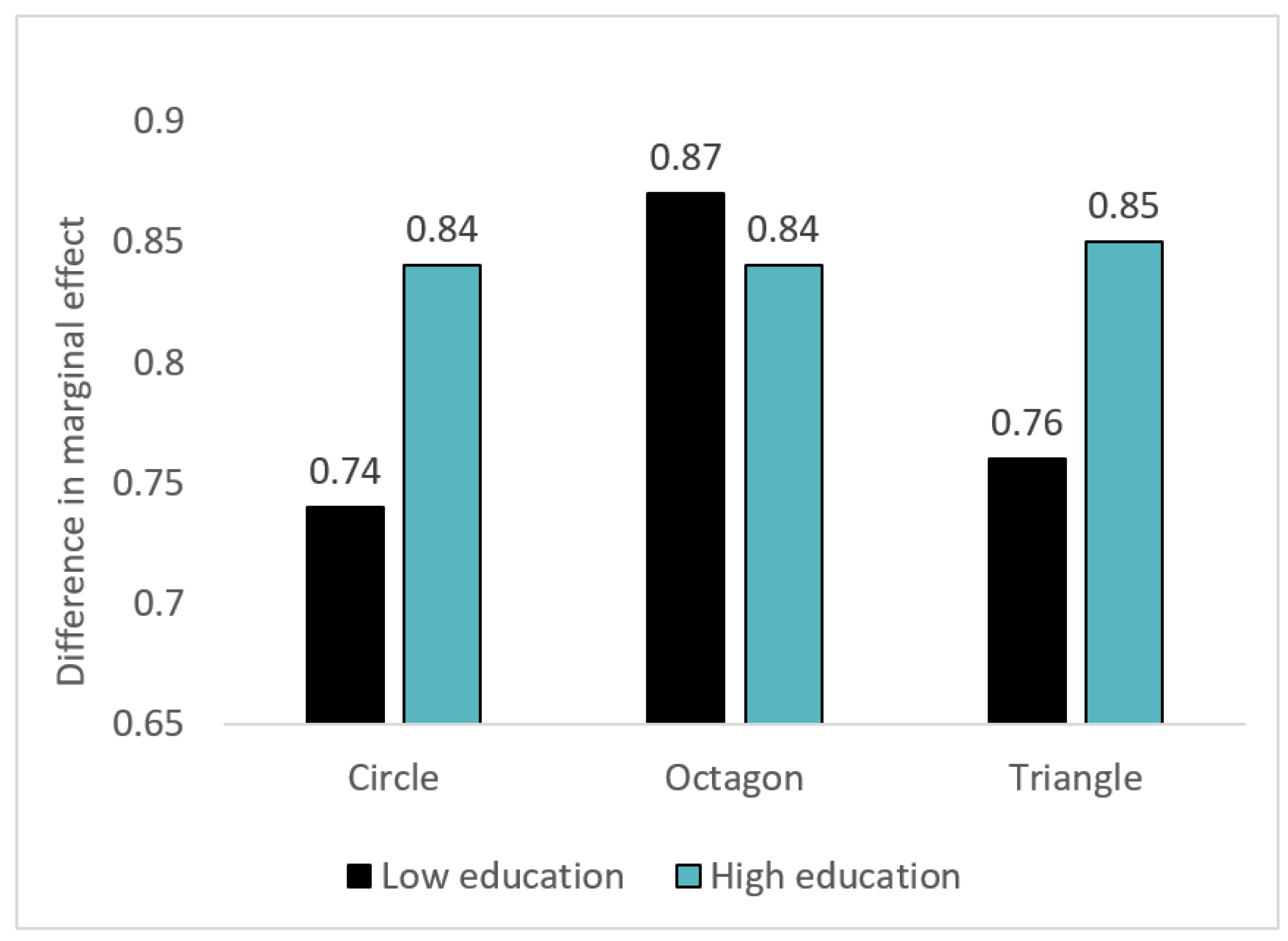

3.4. Interaction of Label Type and Education

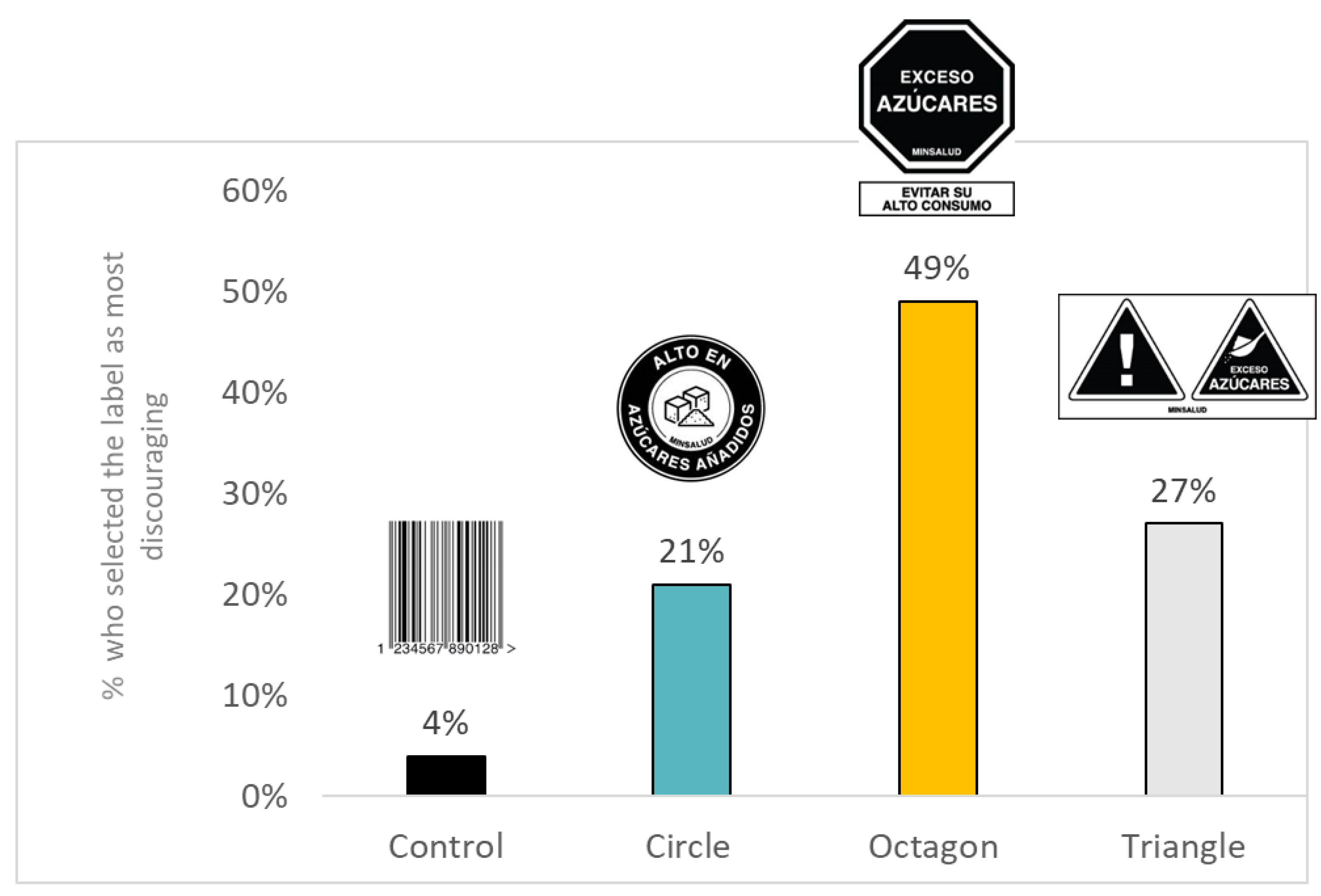

3.5. Other Outcomes

3.6. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Public Health Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Fruit Drink Choice Experiment | ||

|---|---|---|

| Construct | Item | Scale |

| Correctly identifies less healthy product | In your opinion, which one of these products is most unhealthy? | 1 = (image of product with nutrient warning) 2 = (image of product without nutrient warning) |

| Correctly identifies product higher in sugar | Which of these products is highest in sugar? | 1 = (image of product with nutrient warning) 2 = (image of product without nutrient warning) |

| Intentions to purchase | Which of these products would you most want to buy? | 1 = (image of product with nutrient warning) 2 = (image of product without nutrient warning) |

| Label and Single Product Assessment | ||

| Construct | Item | Scale |

| Perceived message effectiveness (PME) | How much does this label make you concerned about the health effects of consuming this product? | 1 = Not at all concerned 2 = A little concerned 3 = Concerned 4 = Very concerned |

| PME | How much does this label makes consuming this product seem pleasant or unpleasant to you? | 1 = Not at all unpleasant 2 = Unpleasant 3 = Pleasant 4 = Very pleasant |

| PME | How much does this label discourage you from wanting to consume this product? | 1 = Not at all discouraged 2 = A little discouraged 3 = Discouraged 4 = Very discouraged |

| Correctly identifies product has excess levels of nutrient of concern | Do you think this product has excess sugar? | 1 = Yes 0 = No [randomize order of yes and no] |

| Attention | How much does this label grab your attention? | 1 = Not at all 2 = A little 3 = A lot 4 = A ton |

| Cognitive elaboration | How much does this label makes you think about the health problems caused by consuming this product? | 1 = Not at all 2 = A little 3 = A lot 4 = A ton |

| Cultural acceptance | How acceptable would this label be in Colombian society? | 1 = Not acceptable 2 = Slightly acceptable 3 = Acceptable 4 = Very acceptable |

| Liking | Do you like this label? | 1 = Yes 0 = No [randomize order of yes and no] |

| Trust | Do you trust this label? | 1 = Yes 0 = No [randomize order of yes and no] |

| Understanding | Is this label easy to understand? | 1 = Yes 0 = No [randomize order of yes and no] |

| Teaching something new | Did this label teach you something new? | 1 = Yes 0 = No [randomize order of yes and no] |

| Intentions to purchase product | How likely would you be to buy this product in the next week, if it were available? | 1 = Not at all likely 2 = A little likely 3 = Likely 4 = Very likely |

| Product perceptions of healthfulness | How unhealthy or healthy would it be for a child aged 1 to 12 to consume products this product every day? | 1 = Very unhealthy 2 = Somewhat unhealthy 3 = Somewhat healthy 4 = Very healthy |

| Product appeal | How unappealing or appealing is this product? | 1 = Very unappealing 2 = Somewhat unappealing 3 = Somewhat appealing 4 = Very appealing |

| PME | Likelihood of Purchasing the Product in the Next Week If It Were Available | Correctly Identified Product as Having Excess of Nutrient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | % | |

| Overall | |||||

| Control | 1.79 | 0.66 | 2.59 | 0.90 | 44% |

| Circle | 2.59 | 0.82 | 2.01 | 0.87 | 87% |

| Octagon | 2.65 | 0.83 | 1.97 | 0.91 | 85% |

| Triangle | 2.61 | 0.82 | 1.99 | 0.88 | 81% |

| Cookies a | |||||

| Control | 1.51 | 0.46 | 2.90 | 0.77 | 20% |

| Circle | 2.46 | 0.84 | 2.11 | 0.88 | 79% |

| Octagon | 2.52 | 0.85 | 2.07 | 0.93 | 77% |

| Triangle | 2.49 | 0.84 | 2.08 | 0.89 | 72% |

| Soda b | |||||

| Control | 2.11 | 0.72 | 2.25 | 0.92 | 89% |

| Circle | 2.75 | 0.78 | 1.93 | 0.87 | 96% |

| Octagon | 2.74 | 0.79 | 1.93 | 0.90 | 97% |

| Triangle | 2.76 | 0.79 | 1.87 | 0.84 | 95% |

| Sliced bread c | |||||

| Control | 1.77 | 0.64 | 2.61 | 0.89 | 25% |

| Circle | 2.56 | 0.81 | 1.98 | 0.85 | 86% |

| Octagon | 2.69 | 0.82 | 1.91 | 0.88 | 82% |

| Triangle | 2.57 | 0.82 | 2.02 | 0.89 | 77% |

| Most Wants to Buy the Labelled Product | Correctly Identified Product Highest in Sugar | Correctly Identified Unhealthy Product | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |

| Added sugar | |||

| Control | 54% | 32% | 41% |

| Circle | 22% | 83% | 77% |

| Octagon | 21% | 84% | 83% |

| Triangle | 24% | 77% | 76% |

| PME | Correctly Identified Product as Having Excess of a Nutrient | Likelihood of Purchasing the Product If It Were Available | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | % | SE | Mean | SE | |

| Product | ||||||

| Cookies a | 2.25 | 0.02 | 63% | 1.1% | 2.29 | 1.9% |

| Soda b | 2.59 | 0.02 | 95% | 0.5% | 1.99 | 2.0% |

| Bread c | 2.40 | 0.02 | 70% | 1.0% | 2.13 | 2.0% |

| Correctly Identified the Less Healthy Fruit Drink as Higher in Sugar | Correctly Identified the Less Healthy Fruit Drink as Less Healthy | Wanted to Purchase the Less Healthy Fruit Drink | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | SE | p | % | SE | p | % | SE | p | |

| Warning | |||||||||

| Control | 32% | 2.2% | n/a | 41% | 2.3% | n/a | 54% | 2.3% | n/a |

| Circle | 83% | 1.7% | <0.001 | 77% | 1.9% | <0.001 | 22% | 1.8% | <0.001 |

| Octagon | 84% | 1.7% | <0.001 | 83% a | 1.7% | <0.001 | 21% | 1.8% | <0.001 |

| Triangle | 77% | 1.9% | <0.001 | 76% | 1.9% | <0.001 | 24% | 1.9% | <0.001 |

| PME | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | Marginal Effect | |

| Cookies a | |||

| Control | 1.51 | 0.02 | n/a |

| Circle | 2.46 | 0.04 | 0.95 * |

| Octagon | 2.52 | 0.04 | 1.01 * |

| Triangle | 2.49 | 0.04 | 0.98 * |

| Soda b | |||

| Control | 2.11 | 0.03 | n/a |

| Circle | 2.74 | 0.03 | 0.64 * |

| Octagon | 2.74 | 0.04 | 0.64 * |

| Triangle | 2.76 | 0.04 | 0.65 * |

| Sliced bread c | |||

| Control | 1.77 | 0.03 | n/a |

| Circle | 2.56 | 0.04 | 0.79 * |

| Octagon | 2.69 | 0.04 | 0.93 * |

| Triangle | 2.57 | 0.04 | 0.81 * |

| Peruvian | Chilean | Proposed Colombian | Triangle Warning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | |

| Warning | ||||

| Control | 15% | 13% | 14% | 16% |

| Circle | 13% | 14% | 24% | 9% |

| Octagon | 18% | 15% | 10% | 13% |

| Triangle | 16% | 19% | 17% | 18% |

| Prior Exposure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| Mean | SE | p | Mean | SE | p | |

| Warning | ||||||

| Control | 1.79 | 0.02 | n/a | 1.79 | 0.02 | n/a |

| Circle | 2.59 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.58 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Octagon | 2.65 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.65 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Triangle | 2.61 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.61 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

References

- Kasper, N.M.; Herrán, O.F.; Villamor, E. Obesity prevalence in Colombian adults is increasing fastest in lower socio-economic status groups and urban residents: Results from two nationally representative surveys. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 2398–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, G.; Castillo-Salgado, C.; Jones-Smith, J.C.; Moulton, L.H. Differences in magnitude and rate of change in adult obesity distribution by age and sex in Mexico, Colombia and Peru, 2005–2010. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 757–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, P.A.; Gomez-Arbelaez, D.; Otero, J.; Gonzalez-Gomez, S.; Molina, D.I.; Sanchez, G.; Arcos, E.; Narvaez, C.; Garcia, H.; Perez, M.; et al. Self-Reported Prevalence of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Relation to Socioeconomic and Educational Factors in Colombia: A Community-Based Study in 11 Departments. Glob. Heart 2020, 15, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Country Report: Colombia. In Health in the Americas; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- Singh, G.M.; Micha, R.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Shi, P.; Andrews, K.G.; Engell, R.E.; Ezzati, M.; Mozaffarian, D. Global, Regional, and National Consumption of Sugar-Sweetened Beverages, Fruit Juices, and Milk: A Systematic Assessment of Beverage Intake in 187 Countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bejarano-Roncancio, J.; Gamboa-Delgado, E.M.; Aya-Baquero, D.H.; Parra, D.C. Los alimentos y bebidas ultra-procesados que ingresan a Colombia por el tratado de libre comercio: ¿influirán en el peso de los colombianos? Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2015, 42, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Plazas, M.; Gomez, L.F.; Miles, D.R.; Parra, D.C.; Taillie, L.S. Nutrition quality of packaged foods in Bogotá, Colombia: A comparison of two nutrient profile models. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Martins, A.P.B.; Canella, D.S.; Baraldi, L.G.; Levy, R.B.; Claro, R.M.; Moubarac, J.; Cannon, G.; Monteiro, C.A. Ultra-processed foods and the nutritional dietary profile in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauber, F.; Louzada, M.L.d.C.; Steele, E.M.; Millett, C.; Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases-Related Dietary Nutrient Profile in the UK (2008–2014). Nutrients 2018, 10, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Neill, D.B.; Teaford, S.F.; Nazmi, A. Alternative MyPlate Menus: Effects of Ultra-Processed Foods on Saturated Fat, Sugar, and Sodium Content. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poti, J.M.; Braga, B.; Qin, B. Ultra-processed Food Intake and Obesity: What Really Matters for Health-Processing or Nutrient Content? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2017, 6, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, V.S.; Popkin, B.M.; Bray, G.A.; Despres, J.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation 2010, 121, 1356–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, E.H.; Hansen, T.W.; Rossing, P.; Johan von Scholten, B. Global Changes in Food Supply and the Obesity Epidemic. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2016, 5, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.; Vanderlee, L.; Vandevijvere, S. Front-of-package nutrition labelling policy: Global progress and future directions. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillie, L.; Hall, M.G.; Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W.; Murukutla, N. Experimental Studies of Front-of-Package Nutrient Warning Labels on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Ultra-Processed Foods: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummon, A.H.; Hall, M.G. Sugary drink warnings: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, T.; Fierro, C.; Reyes, M.; Carpentier, F.R.D.; Taillie, L.S.; Corvalán, C. Responses to the Chilean law of food labeling and advertising: Exploring knowledge, perceptions and behaviors of mothers of young children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillie, L.S.; Reyes, M.; Colchero, M.A.; Popkin, B.; Corvalán, C. An evaluation of Chile’s Law of Food Labeling and Advertising on sugar-sweetened beverage purchases from 2015 to 2017: A before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M.; Taillie, L.S.; Popkin, B.; Kanter, R.; Vandevijvere, S.; Corvalán, C. Changes in the amount of nutrient of packaged foods and beverages after the initial implementation of the Chilean Law of Food Labelling and Advertising: A nonexperimental prospective study. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombia Tendrá Etiquetado Nutricional en los Alimentos Envasados; 34; Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social: Bogotá, Colombia, 2020.

- Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model; Pan American Health Organization: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Corvalán, C.; Reyes, M.; Garmendia, M.L.; Uauy, R. Structural responses to the obesity and non-communicable diseases epidemic: Update on the Chilean law of food labelling and advertising. Obes. Rev. 2018, 20, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, S.; Vanderlee, L.; Acton, R.; Mahamad, S.; Hammond, D. The impact of front-of-package label design on consumer understanding of nutrient amounts. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillon-Keren, M.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Goldsmith, R.; Safra, C.; Shai, I.; Fayman, G.; Berry, E.; Tirosh, A.; Dicker, D.; Froy, O.; et al. Development of Criteria for a Positive Front-of-Package Food Labeling: The Israeli Case. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummon, A.H.; Taillie, L.S.; Golden, S.D.; Hall, M.G.; Ranney, L.M.; Brewer, N.T. Sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings and purchases: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manual on Advertising Warnings Approved Pursuant to the Provisions of Law No. 30021, Law to Promote Healthy Eating for Children and Adolescents, and Its Regulations approved by Supreme Decree No. 017-2017-SA; Peru Supreme Decree 012-2018-SA; Ministry of Production: Lima, Peru, 2018.

- Khandpur, N.; Mais, L.A.; Sato, P.D.M.; Martins, A.P.B.; Spinillo, C.G.; Rojas, C.F.U.; Garcia, M.T.; Jaime, P.C. Choosing a front-of-package warning label for Brazil: A randomized, controlled comparison of three different label designs. Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard, A.J.; Mackert, M.S.; Bock, M.A.; Love, B.; Dudo, A.; Atkinson, L. Visual assertions: Effects of photo manipulation and dual processing for food advertisements. Vis. Commun. 2018, 25, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, S.A.; Noar, S.M.; Gottfredson, N.C.; Boynton, M.H.; Ribisl, K.M.; Brewer, N.T. UNC perceived message effectiveness: Validation of a brief scale. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 53, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grummon, A.H.; Hall, M.G.; Taillie, L.S.; Brewer, N.T. How should sugar-sweetened beverage health warnings be designed? A randomized experiment. Prev. Med. 2019, 121, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noar, S.M.; Barker, J.; Bell, T.; Yzer, M. Does Perceived Message Effectiveness Predict the Actual Effectiveness of Tobacco Education Messages? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Commun. 2020, 35, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.C.; Nonnemaker, J.; Duke, J.; Farrelly, M.C. Perceived effectiveness of cessation advertisements: The importance of audience reactions and practical implications for media campaign planning. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, M. Development of the Chilean front-of-package food warning label. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No Comas Más Mentiras—Colombia Necesita la #LeyComidaChatarra Jugos. 2019. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mb2_xiWUm38 (accessed on 1 September 2020).

- Moran, A.J.; Roberto, C.A. Health Warning Labels Correct Parents’ Misperceptions About Sugary Drink Options. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2018, 55, e19–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Zhang, D.; Morgan, J.C.; Ross, J.C.; Osman, A.; Boynton, M.H.; Mendel, J.R.; Brewer, N.T. Similarities and Differences in Tobacco Control Research Findings From Convenience and Probability Samples. Ann. Behav. Med. 2018, 53, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Arm | ||

| Control | 481 | 24% |

| Circle | 513 | 26% |

| Octagon | 503 | 25% |

| Triangle | 500 | 25% |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 | 399 | 20% |

| 25–34 | 520 | 26% |

| 35–44 | 419 | 21% |

| 45–54 | 379 | 19% |

| 55+ | 280 | 14% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 983 | 49% |

| Female | 1005 | 50% |

| Other gender identity | 9 | 0% |

| Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) | ||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 76 | 4% |

| Healthy weight (18.5–24.9) | 920 | 48% |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 676 | 35% |

| Obese (>29.9) | 253 | 13% |

| Education Level | ||

| Low (High school diploma or less) | 1001 | 50% |

| High (More than a high school diploma) | 996 | 50% |

| Region | ||

| Atlantica | 418 | 21% |

| Oriental | 395 | 20% |

| Central | 491 | 25% |

| Pacifica | 330 | 17% |

| Orinoquia | 21 | 1% |

| Bogota | 342 | 17% |

| Children | ||

| Yes | 1309 | 66% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Indigenous | 58 | 3% |

| Black, mixed, afro-descendent | 242 | 12% |

| Other ethnic group | 390 | 20% |

| No ethnic group | 1307 | 65% |

| PME | Correctly Identified Product as Having Excess of a Nutrient | Likelihood of Purchasing the Product if It Were Available | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | p | % | SE | p | Mean | SE | p | |

| Warning | |||||||||

| Control | 1.79 | 0.02 | n/a | 46% | 1.9% | n/a | 2.59 | 0.03 | n/a |

| Circle | 2.59 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 89% | 1.1% | <0.001 | 2.01 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Octagon | 2.65 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 88% | 1.1% | <0.001 | 1.97 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Triangle | 2.61 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 84% a | 1.3% | <0.001 | 1.99 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Control | Circle | Octagon | Triangle | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SE | p | Mean | SE | p | Mean | SE | p | Mean | SE | p | |

| Grabbed attention | 2.23 | 0.03 | n/a | 2.49 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.57 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.51 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Made them think about health problems from consuming the product | 1.79 | 0.03 | n/a | 2.74 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.84 a | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.68 | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Would be acceptable in Colombian society | 2.70 | 0.03 | n/a | 2.60 | 0.04 | 0.236 | 2.65 | 0.04 | 1.000 | 2.57 | 0.04 | 0.050 |

| Would be healthy for a child aged 1 to 12 to consume the product every day | 2.28 | 0.03 | n/a | 1.60 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 1.56 a | 0.03 | <0.001 | 1.69 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Perceived product appeal | 2.68 | 0.03 | n/a | 2.16 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.16 | 0.03 | <0.001 | 2.14 | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| % | SE | p | % | SE | p | % | SE | p | % | SE | p | |

| Liked the label | 60% | 2.2% | n/a | 63% | 2.1% | 1.000 | 71% b | 2.0% | 0.001 | 61% | 2.2% | 1.000 |

| Easy to understand the label | 68% | 2.1% | n/a | 92% | 1.2% | <0.001 | 93% | 1.2% | <0.001 | 89% | 1.4% | <0.001 |

| Label taught something new | 30% | 0.7% | n/a | 75% | 0.7% | <0.001 | 77% b | 1.2% | <0.001 | 74% | 0.6% | <0.001 |

| Trusted the label | 49% | 2.3% | n/a | 67% | 2.1% | <0.001 | 73% a | 2.0% | <0.001 | 63% | 2.2% | <0.001 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taillie, L.S.; Hall, M.G.; Gómez, L.F.; Higgins, I.; Bercholz, M.; Murukutla, N.; Mora-Plazas, M. Designing an Effective Front-of-Package Warning Label for Food and Drinks High in Added Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat in Colombia: An Online Experiment. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3124. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103124

Taillie LS, Hall MG, Gómez LF, Higgins I, Bercholz M, Murukutla N, Mora-Plazas M. Designing an Effective Front-of-Package Warning Label for Food and Drinks High in Added Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat in Colombia: An Online Experiment. Nutrients. 2020; 12(10):3124. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103124

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaillie, Lindsey Smith, Marissa G. Hall, Luis Fernando Gómez, Isabella Higgins, Maxime Bercholz, Nandita Murukutla, and Mercedes Mora-Plazas. 2020. "Designing an Effective Front-of-Package Warning Label for Food and Drinks High in Added Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat in Colombia: An Online Experiment" Nutrients 12, no. 10: 3124. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103124

APA StyleTaillie, L. S., Hall, M. G., Gómez, L. F., Higgins, I., Bercholz, M., Murukutla, N., & Mora-Plazas, M. (2020). Designing an Effective Front-of-Package Warning Label for Food and Drinks High in Added Sugar, Sodium, or Saturated Fat in Colombia: An Online Experiment. Nutrients, 12(10), 3124. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12103124