A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Clinical Study of the Effects of Alpha-s1 Casein Hydrolysate on Sleep Disturbance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

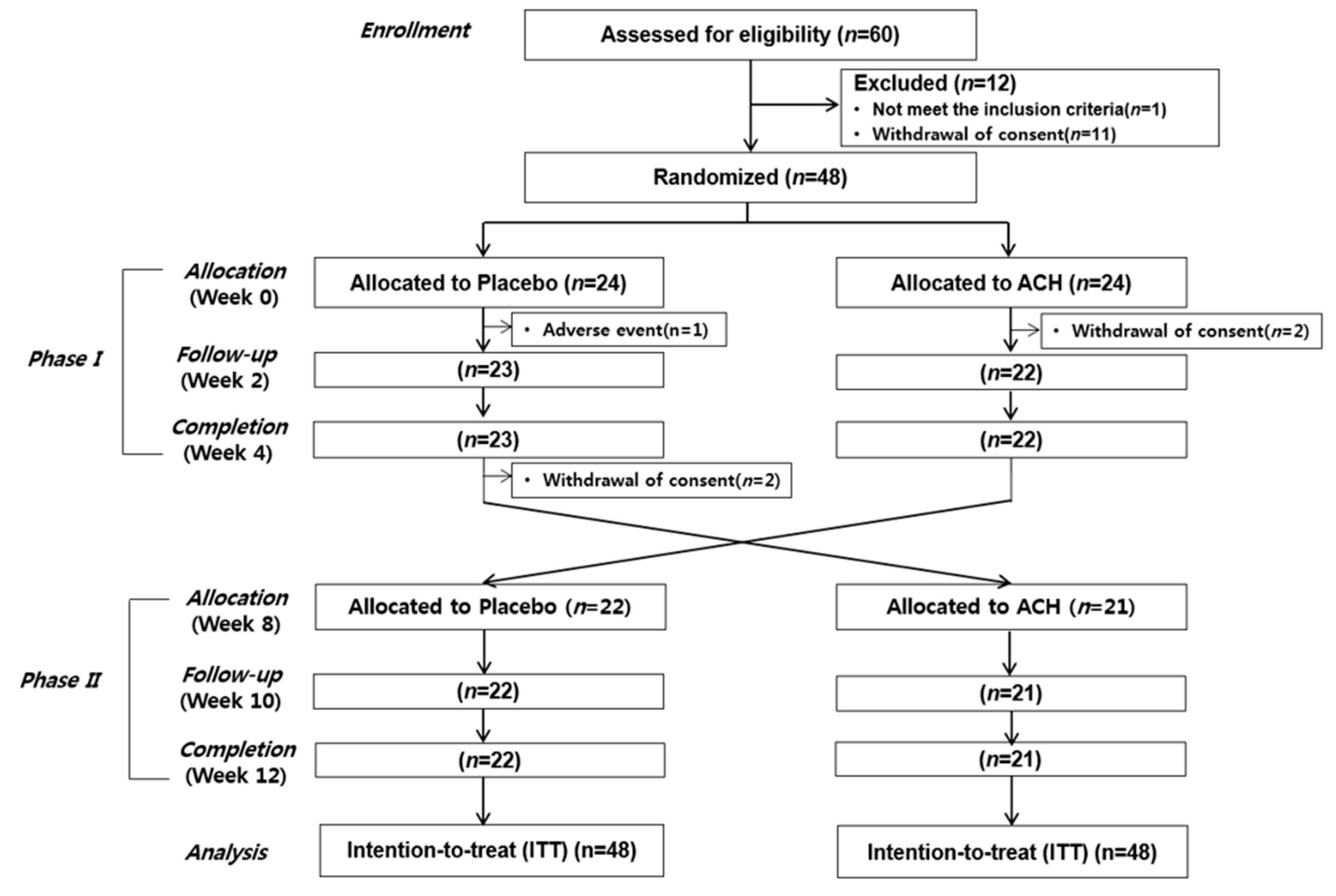

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Tested Products

2.4. Sleep Quantity and Quality Assessment

2.4.1. Sleep and Mood Questionnaire Scales

2.4.2. Sleep Diary

2.4.3. Actigraphy

2.4.4. Polysomnography (PSG)

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Sleep and Mood Questionnaire Scales

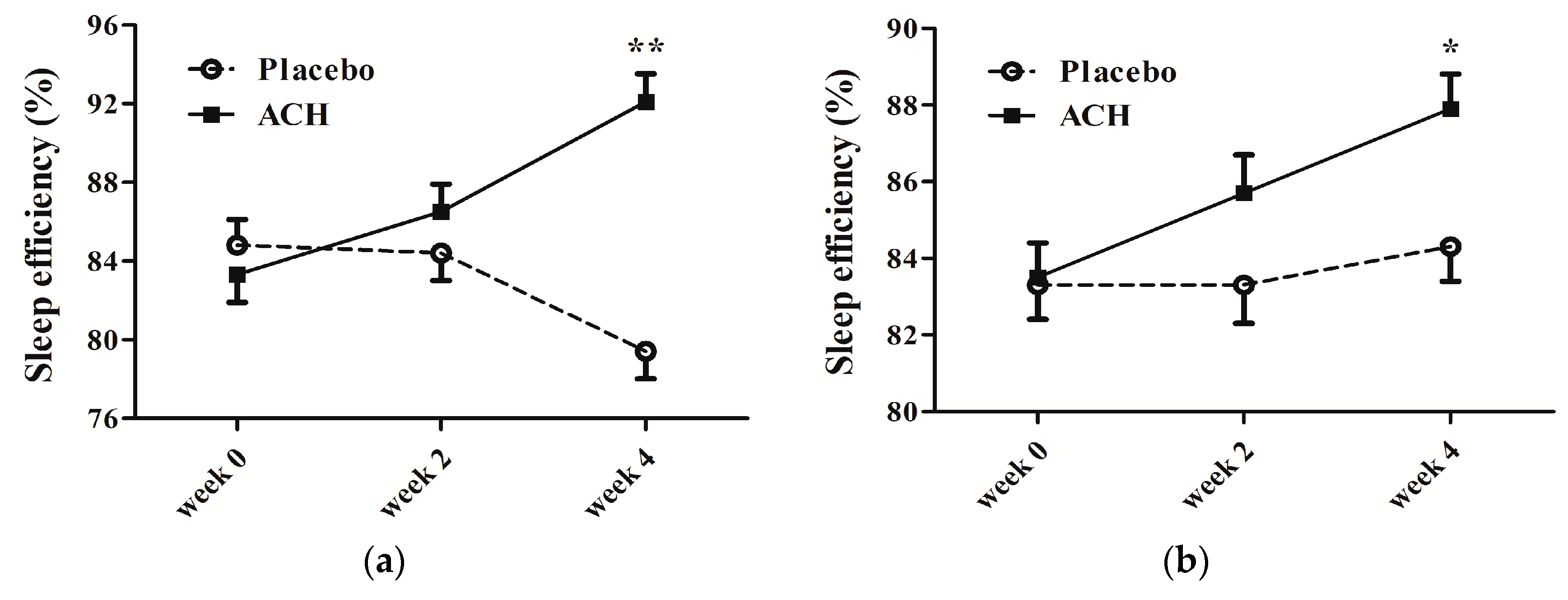

3.3. Subjective and Objective Sleep Profile Monitoring

3.4. PSG Measures

3.5. Safety Evaluation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| ACH | alpha-s1 casein hydrolysate |

| EEG | electroencephalogram |

| SL | sleep latency |

| PSQI | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| ISI | Insomnia Severity Index |

| OSA | obstructive sleep apnea |

| RLS | restless leg syndrome |

| PLMS | periodic leg movement syndrome |

| BMI | body mass index |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| CRIS | Clinical Research Information Service |

| EDS | excessive daytime sleepiness |

| ESS | Epworth Sleepiness Scale |

| FSS | Fatigue Severity Scale |

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory |

| TIB | time in bed |

| TST | total sleep time |

| WASO | wake after sleep onset |

| SE | sleep efficiency |

| PSG | polysomnography |

| EMG | electromyography |

| EOG | electrooculogram |

| ECG | electrocardiogram |

| AASM | American Academy of Sleep Medicine |

| ITT | intention to treat |

| SD | standard deviation |

| SAS | statistical analysis system |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| NREM | non-rapid eye movement |

| REM | rapid eye movement |

| SWS | slow wave sleep |

| AHI | apnea-hypopnea index |

References

- Chung, K.-F.; Yeung, W.-F.; Ho, F.Y.-Y.; Yung, K.-P.; Yu, Y.-M.; Kwok, C.-W. Cross-cultural and comparative epidemiology of insomnia: The Diagnostic and statistical manual (DSM), International classification of diseases (ICD) and International classification of sleep disorders (ICSD). Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.W.; Shin, W.C.; Yun, C.H.; Hong, S.B.; Kim, J.; Earley, C.J. Epidemiology of insomnia in Korean adults: Prevalence and associated factors. J. Clin. Neurol. 2009, 5, 20–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M. Epidemiology of insomnia: What we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med. Rev. 2002, 6, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay-Stacey, M.; Attarian, H.J.B. Advances in the management of chronic insomnia. BMJ 2016, 354, i2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateia, M.J.; Buysse, D.J.; Krystal, A.D.; Neubauer, D.N.; Heald, J.L. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 307–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victorri-Vigneau, C.; Dailly, E.; Veyrac, G.; Jolliet, P. Evidence of zolpidem abuse and dependence: Results of the French Centre for Evaluation and Information on Pharmacodependence (CEIP) network survey. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 64, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.-D.; Lin, C.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Lin, H.-C.; Kang, J.-H. Zolpidem use and the risk of injury: A population-based follow-up study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithamparanathan, K.; Sadera, A.; Leung, L. Adverse effects of benzodiazepine use in elderly people: A meta-analysis. Asian J. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2012, 7, 107–111. [Google Scholar]

- Sarris, J.; Panossian, A.; Schweitzer, I.; Stough, C.; Scholey, A. Herbal medicine for depression, anxiety and insomnia: A review of psychopharmacology and clinical evidence. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011, 21, 841–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimecki, M.; Kruzel, M.L. Milk-derived proteins and peptides of potential therapeutic and nutritive value. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2007, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Alén, M.; Wang, K.; Tenhunen, J.; Wiklund, P.; Partinen, M.; Cheng, S. Effect of six-month diet intervention on sleep among overweight and obese men with chronic insomnia symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peuhkuri, K.; Sihvola, N.; Korpela, R. Diet promotes sleep duration and quality. Nutr. Res. 2012, 32, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, S.D.; Morgan, K.; Espie, C.A. Insomnia and health-related quality of life. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silber, B.; Schmitt, J. Effects of tryptophan loading on human cognition, mood, and sleep. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010, 34, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubenik, G.A. Gastrointestinal melatonin: Localization, function, and clinical relevance. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2002, 47, 2336–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, P.K.; Roberts, R.M.; Harris, J.K. A systematic review assessing bidirectionality between sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. Sleep 2013, 36, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Jeon, H.J.; Hong, J.P.; Bae, J.N.; Lee, J.Y.; Chang, S.M.; Lee, Y.M.; Son, J.; Cho, M.J. DSM-IV psychiatric comorbidity according to symptoms of insomnia: A nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2012, 47, 2019–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staner, L. Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Dong, J.-W.; Zhao, J.-H.; Tang, L.-N.; Zhang, J.-J. Herbal insomnia medications that target GABAergic systems: A review of the psychopharmacological evidence. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2014, 12, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohler, H. The GABA system in anxiety and depression and its therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology 2012, 62, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, S.; Padula, A.; Moore, D.; Patterson, M.; Mehling, W. Valerian for sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. 2006, 119, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases, J.; Ibarra, A.; Feuillere, N.; Roller, M.; Sukkar, S.G. Pilot trial of Melissa officinalis L. leaf extract in the treatment of volunteers suffering from mild-to-moderate anxiety disorders and sleep disturbances. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 4, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngan, A.; Conduit, R. A double-blind, placebo-controlled investigation of the effects of Passiflora incarnata (Passionflower) herbal tea on subjective sleep quality. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 1153–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, L.; Sánchez, C.; Bravo, R.; Rodriguez, A.; Barriga, C.; Juánez, J. The sedative effects of hops (Humulus lupulus), a component of beer, on the activity/rest rhythm. Acta Physiol. Hung. 2012, 99, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, R.A.; Poppitt, S.D. Milk protein for improved metabolic health: A review of the evidence. Nutr. Metab. 2013, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Desor, D.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, W.; Kim, K.; Jun, J.; Pyun, K.; Shim, I. Efficacy of α s1-casein hydrolysate on stress-related symptoms in women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, S.; Matsuura, K.; Gotou, T.; Nishimura, S.; Kajimoto, O.; Yabune, M.; Kajimoto, Y.; Yamamoto, N. Antihypertensive effect of casein hydrolysate in a placebo-controlled study in subjects with high-normal blood pressure and mild hypertension. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 94, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, M.; Lefranc–Millot, C.; Desor, D.; Demagny, B.; Bourdon, L. Effects of a tryptic hydrolysate from bovine milk α S1–Casein on hemodynamic responses in healthy human volunteers facing successive mental and physical stress situations. Eur. J. Nutr. 2005, 44, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, M.; Lalonde, R.; Schroeder, H.; Desor, D. Anxiolytic-like effects and safety profile of a tryptic hydrolysate from bovine alpha s1-casein in rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 23, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclo, L.; Perrin, E.; Driou, A.; Papadopoulos, V.; Boujrad, N.; Vanderesse, R.; Boudier, J.-F.; Desor, D.; Linden, G.; Gaillard, J.-L. Characterization of α-casozepine, a tryptic peptide from bovine αs1-Casein with benzodiazepine-Like activity. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 1780–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecouvey, M.; Frochot, C.; Miclo, L.; Orlewski, P.; Driou, A.; Linden, G.; Gaillard, J.L.; Marraud, M.; Cung, M.T.; Vanderesse, R. Two-Dimensional 1H-NMR and CD Structural Analysis in a Micellar Medium of a Bovine αs1-Casein Fragment having Benzodiazepine-Like Properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 248, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dela Pena, I.J.I.; Kim, H.J.; de la Pena, J.B.; Kim, M.; Botanas, C.J.; You, K.Y.; Woo, T.; Lee, Y.S.; Jung, J.-C.; Kim, K.-M. A tryptic hydrolysate from bovine milk αs1-casein enhances pentobarbital-Induced sleep in mice via the GABAA receptor. Behav. Brain Res. 2016, 313, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayeh, T.; Leem, Y.H.; Kim, K.M.; Jung, J.C.; Schwarz, J.; Oh, K.W.; Oh, S. Administration of Alphas1-Casein Hydrolysate Increases Sleep and Modulates GABAA Receptor Subunit Expression. Biomol. Ther. 2018, 26, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholey, A.; Benson, S.; Gibbs, A.; Perry, N.; Sarris, J.; Murray, G. Exploring the Effect of Lactium and Zizyphus Complex on Sleep Quality: A Double-Blind, Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Hilaire, Z.d.; Messaoudi, M.; Desor, D.; Kobayashi, T. Effects of a bovine alpha S1-Casein tryptic hydrolysate (CTH) on sleep disorder in Japanese general population. Open Sleep J. 2009, 2, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiers, J.; Bakker, G.; Bakker-Zierikzee, A.; Smits, M.; Schaafsma, A. Sleep improving effects of enriched milk: A randomised double-blind trial in adult women with insomnia. Nutrafoods 2007, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien, C.H.; Vallières, A.; Morin, C.M. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001, 2, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosti-Otajärvi, E.; Hämäläinen, P.; Wiksten, A.; Hakkarainen, T.; Ruutiainen, J. Validity and reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale in Finnish multiple sclerosis patients. Brain Behav. 2017, 7, e00743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Hwang, S.-T.; Hong, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Investig. 2017, 14, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-K.; Lee, E.-H.; Hwang, S.-T.; Hong, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Psychometric properties of the beck anxiety inventory in the community-dwelling sample of Korean adults. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 822–830. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, R.B.; Brooks, R.; Gamaldo, C.E.; Harding, S.M.; Marcus, C.; Vaughn, B. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications; American Academy of Sleep Medicine: Darien, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Howatson, G.; Bell, P.G.; Tallent, J.; Middleton, B.; McHugh, M.P.; Ellis, J. Effect of tart cherry juice (Prunus cerasus) on melatonin levels and enhanced sleep quality. Eur. J. Nutr. 2012, 51, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfano, C.A.; Patriquin, M.A.; De Los Reyes, A. Subjective–objective sleep comparisons and discrepancies among clinically-anxious and healthy children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2015, 43, 1343–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsawh, H.J.; Stein, M.B.; Belik, S.-L.; Jacobi, F.; Sareen, J. Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality, and functional impairment in a community sample. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calhoun, P.S.; Wiley, M.; Dennis, M.F.; Means, M.K.; Edinger, J.D.; Beckham, J.C. Objective evidence of sleep disturbance in women with posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma Stress 2007, 20, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edinger, J.D.; Bonnet, M.H.; Bootzin, R.R.; Doghramji, K.; Dorsey, C.M.; Espie, C.A.; Jamieson, A.O.; McCall, W.V.; Morin, C.M.; Stepanski, E.J. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep 2004, 27, 1567–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, G.J.; Best, J.R.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Measuring sleep quality in older adults: A comparison using subjective and objective methods. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, R.; de Campos Mazo, D.F.; Carrilho, F.J. Lactose intolerance: Diagnosis, genetic, and clinical factors. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2012, 5, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.G.; Rybarczyk, B.D.; Perrin, P.B.; Leszczyszyn, D.; Stepanski, E. The discrepancy between subjective and objective measures of sleep in older adults receiving CBT for comorbid insomnia. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 1108–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscemi, N.; Vandermeer, B.; Friesen, C.; Bialy, L.; Tubman, M.; Ospina, M.; Klassen, T.P.; Witmans, M. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: A meta-analysis of RCTs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | N = 48 |

|---|---|

| Age (year) | 49.0 ± 11.9 |

| Gender (male/female) | 17/31 |

| Menopause | 24/31 (77.4%) |

| Postmenopausal period (month) | 72.0 ± 57.2 |

| Sleep disturbance duration (month) | 57.6 ± 91.3 |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | 11.4 ± 1.9 |

| Insomnia Severity Index | 13.2 ± 3.8 |

| Family history of insomnia | 6 (12.5%) |

| Caffeine amount (servings/day) | 1.2 ± 1.3 |

| Alcohol drinker | 31 (64.6%) |

| Alcohol amount (g/week) | 29.9 ± 37.4 |

| Smoker | 2 (4.2%) |

| Smoking amount (cigarettes/day) | 0.3 ± 1.1 |

| Anthropometric measures | |

| Body weight (kg) | 60.3 ± 10.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.8 ± 2.8 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 80.0 ± 7.9 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 33.9 ± 2.8 |

| Vital signs | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 119.4 ± 12.8 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 74.5 ± 12.1 |

| Pulse rate (beats/min) | 71.2 ± 12.3 |

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.4 ± 0.3 |

| Variables | Placebo | ACH | p-Value † | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Time | Group × Time | |||||||

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 10.14 | ± | 0.42 | 9.79 | ± | 0.42 | |||

| Week 2 | 8.23 | ± | 0.42 | 8.79 | ± | 0.43 | |||

| Week 4 | 8.41 | ± | 0.42 | 8.51 | ± | 0.43 | 0.668 | <0.001 ** | 0.211 |

| Insomnia Severity Index | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 12.15 | ± | 0.73 | 12.08 | ± | 0.73 | |||

| Week 2 | 9.75 | ± | 0.73 | 10.50 | ± | 0.74 | |||

| Week 4 | 9.44 | ± | 0.73 | 10.04 | ± | 0.74 | 0.406 | <0.001 ** | 0.523 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 6.30 | ± | 0.58 | 6.72 | ± | 0.58 | |||

| Week 2 | 6.10 | ± | 0.58 | 5.91 | ± | 0.59 | |||

| Week 4 | 6.02 | ± | 0.58 | 5.67 | ± | 0.59 | 0.920 | 0.039 | 0.324 |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 31.60 | ± | 1.64 | 32.55 | ± | 1.65 | |||

| Week 2 | 31.00 | ± | 1.65 | 32.64 | ± | 1.67 | |||

| Week 4 | 30.67 | ± | 1.65 | 31.29 | ± | 1.67 | 0.276 | 0.462 | 0.854 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 11.65 | ± | 1.25 | 12.37 | ± | 1.26 | |||

| Week 2 | 11.49 | ± | 1.26 | 12.28 | ± | 1.27 | |||

| Week 4 | 10.41 | ± | 1.26 | 10.79 | ± | 1.27 | 0.464 | 0.008 * | 0.912 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | |||||||||

| Week 0 | 8.04 | ± | 1.11 | 7.71 | ± | 1.11 | |||

| Week 2 | 8.41 | ± | 1.11 | 7.72 | ± | 1.12 | |||

| Week 4 | 7.70 | ± | 1.11 | 7.09 | ± | 1.12 | 0.363 | 0.362 | 0.924 |

| Variables | Placebo | ACH | p-Value † | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 0 | Week 4 | Week 0 | Week 4 | Group | Time | Group × Time | |

| TIB (min) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 470.4 ± 12.1 | 455.9 ± 12.4 | 464.5 ± 12.2 | 459.5 ± 12.2 | 0.883 | 0.134 | 0.465 |

| Actigraphy | 432.6 ± 17.0 | 412.0 ± 17.1 | 431.5 ± 17.1 | 424.0 ± 17.5 | 0.737 | 0.342 | 0.656 |

| TST (min) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 395.7 ± 10.0 | 361.0 ± 10.3 | 385.3 ± 10.1 | 422.7 ± 10.1 | <0.001 ** | 0.796 | <0.001 ** |

| Actigraphy | 362.8 ± 16.5 | 347.8 ± 16.6 | 360.1 ± 16.6 | 376.1 ± 17.0 | 0.414 | 0.971 | 0.270 |

| SL (min) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 33.2 ± 4.4 | 50.5 ± 4.6 | 39.5 ± 4.5 | 18.3 ± 4.5 | 0.011 * | 0.598 | <0.001 ** |

| Actigraphy | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 2.8 ± 1.6 | 0.975 | 0.288 | 0.063 |

| SE (%) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 84.9 ± 1.3 | 79.4 ± 1.3 | 83.3 ± 1.3 | 92.1 ± 1.3 | <0.001 ** | 0.108 | <0.001 ** |

| Actigraphy | 83.3 ± 0.9 | 84.3 ± 1.0 | 83.6 ± 0.9 | 88.0 ± 1.0 | 0.013 * | <0.001 ** | 0.007 * |

| WASO (min) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 15.7 ± 3.4 | 29.6 ± 3.6 | 17.0 ± 3.5 | 11.9 ± 3.5 | 0.039 | 0.097 | <0.001 ** |

| Actigraphy | 53.2 ± 3.8 | 49.2 ± 3.9 | 55.6 ± 3.9 | 38.9 ± 3.9 | 0.228 | 0.002 * | 0.053 |

| Awake (N) | |||||||

| Sleep diary | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.001 ** | 0.216 | 0.077 |

| Actigraphy | 16.1 ± 1.1 | 15.2 ± 1.1 | 15.6 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 0.157 | 0.024 | 0.240 |

| Variables | Sleep Diary | Actigraphy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | ACH | p-Value † | Placebo | ACH | p-Value † | |

| Increased TST | 24% | 79% | <0.001 ** | 41% | 61% | 0.073 |

| Decreased SL | 30% | 67% | 0.001 ** | 29% | 46% | 0.119 |

| Increased SE | 24% | 85% | <0.001 ** | 63% | 85% | 0.031 |

| Decreased WASO | 32% | 51% | 0.096 | 61% | 67% | 0.597 |

| Decreased Awakes | 43% | 54% | 0.355 | 56% | 64% | 0.465 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, B.; Kwon, E.; Lee, J.E.; Chun, M.Y.; Lee, C.Y.; Boulier, A.; Oh, S.; et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Clinical Study of the Effects of Alpha-s1 Casein Hydrolysate on Sleep Disturbance. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071466

Kim HJ, Kim J, Lee S, Kim B, Kwon E, Lee JE, Chun MY, Lee CY, Boulier A, Oh S, et al. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Clinical Study of the Effects of Alpha-s1 Casein Hydrolysate on Sleep Disturbance. Nutrients. 2019; 11(7):1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071466

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hyeon Jin, Jiyeon Kim, Seungyeon Lee, Bosil Kim, Eunjin Kwon, Jee Eun Lee, Min Young Chun, Chan Young Lee, Audrey Boulier, Seikwan Oh, and et al. 2019. "A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Clinical Study of the Effects of Alpha-s1 Casein Hydrolysate on Sleep Disturbance" Nutrients 11, no. 7: 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071466

APA StyleKim, H. J., Kim, J., Lee, S., Kim, B., Kwon, E., Lee, J. E., Chun, M. Y., Lee, C. Y., Boulier, A., Oh, S., & Lee, H. W. (2019). A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Clinical Study of the Effects of Alpha-s1 Casein Hydrolysate on Sleep Disturbance. Nutrients, 11(7), 1466. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071466