Effectiveness of Workplace Nutrition Programs on Anemia Status among Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh: A Program Evaluation

Abstract

1. Introduction

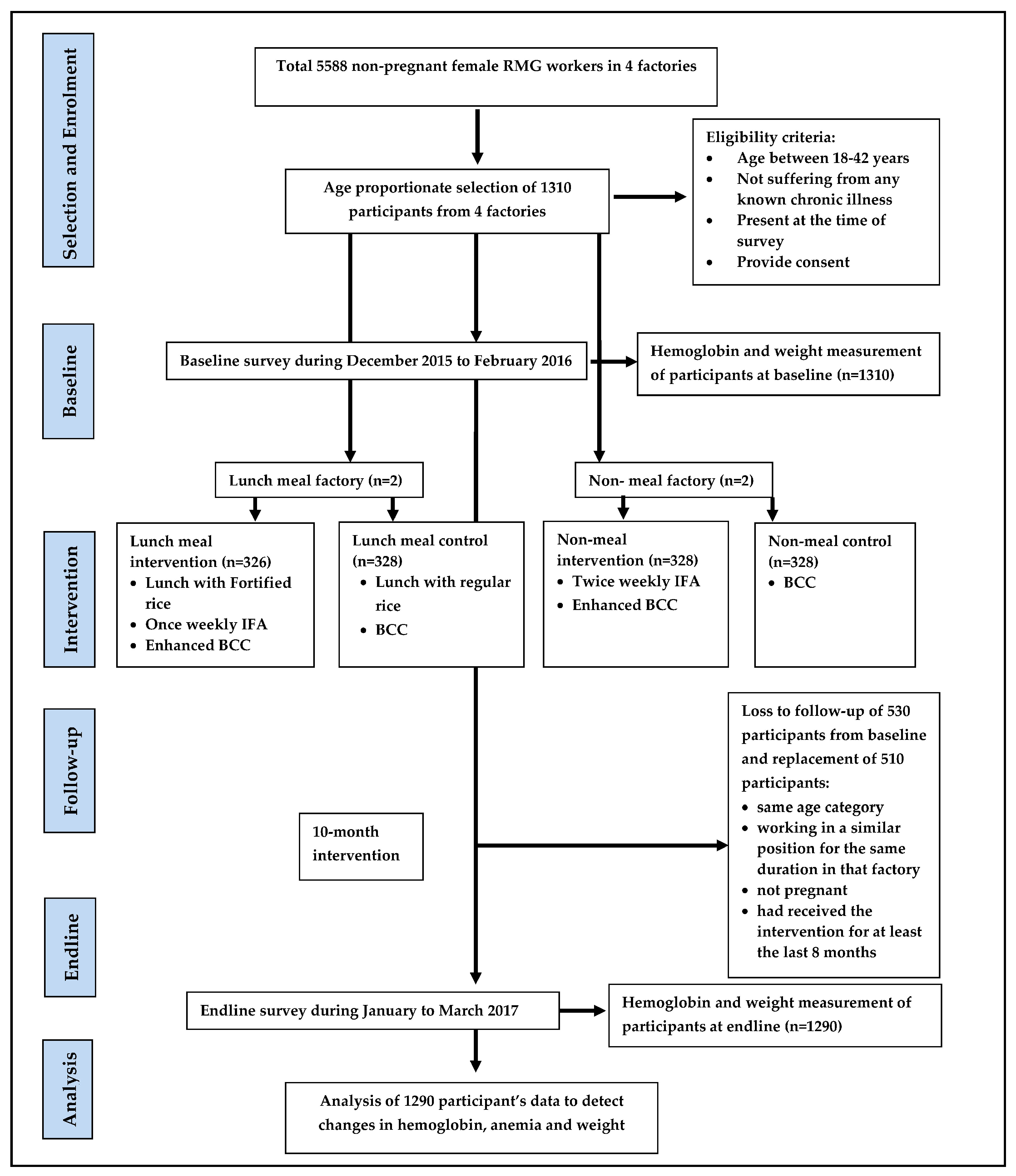

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Site

2.2. Program/Intervention Description

Composition of the Different Packages with Rationale

- (i)

- Intervention factory with a lunch program: the iron/folate supplement was provided once weekly to non-pregnant women of reproductive age. This increased the mean daily intake equivalent of iron by 8.6 mg/day and of folate by 57 µg/day, equivalent to 15% or 29% of the RNI for iron at low or moderate bioavailability, respectively, and to 14% of the RNI for folate.

- (ii)

- Intervention factory without a lunch program: the iron/folate supplement was provided twice weekly to non-pregnant women of reproductive age. This will increase the mean daily intake equivalent of iron by 17.1 mg/day and of folate by 114 µg/day, equivalent to 30% or 58% of the RNI for iron and low or moderate bioavailability, respectively, and to 29% of the RNI for folate. The twice-weekly doses considered, as they were not getting fortified rice so there will be a gap in iron-folate requirements (Table S3).

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Enrolment of Study Participants

2.5. Questionnaires

2.6. Anthropometric Measurement

2.7. Blood Sample Collection and Analysis

2.8. Qualitative Interviews

2.9. Outcome

2.10. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

2.10.1. Quantitative Data

2.10.2. Qualitative Data

2.11. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Socio-Demographic Status

3.2. Baseline Factory Food Experience and Satisfaction

3.3. Food and Nutrition Knowledge and Adherence to Iron-Folic Acid (IFA) Tablet

3.4. Water, Sanitation and Personal Hygiene Practice

3.5. Self-Reported Sickness and Absenteeism

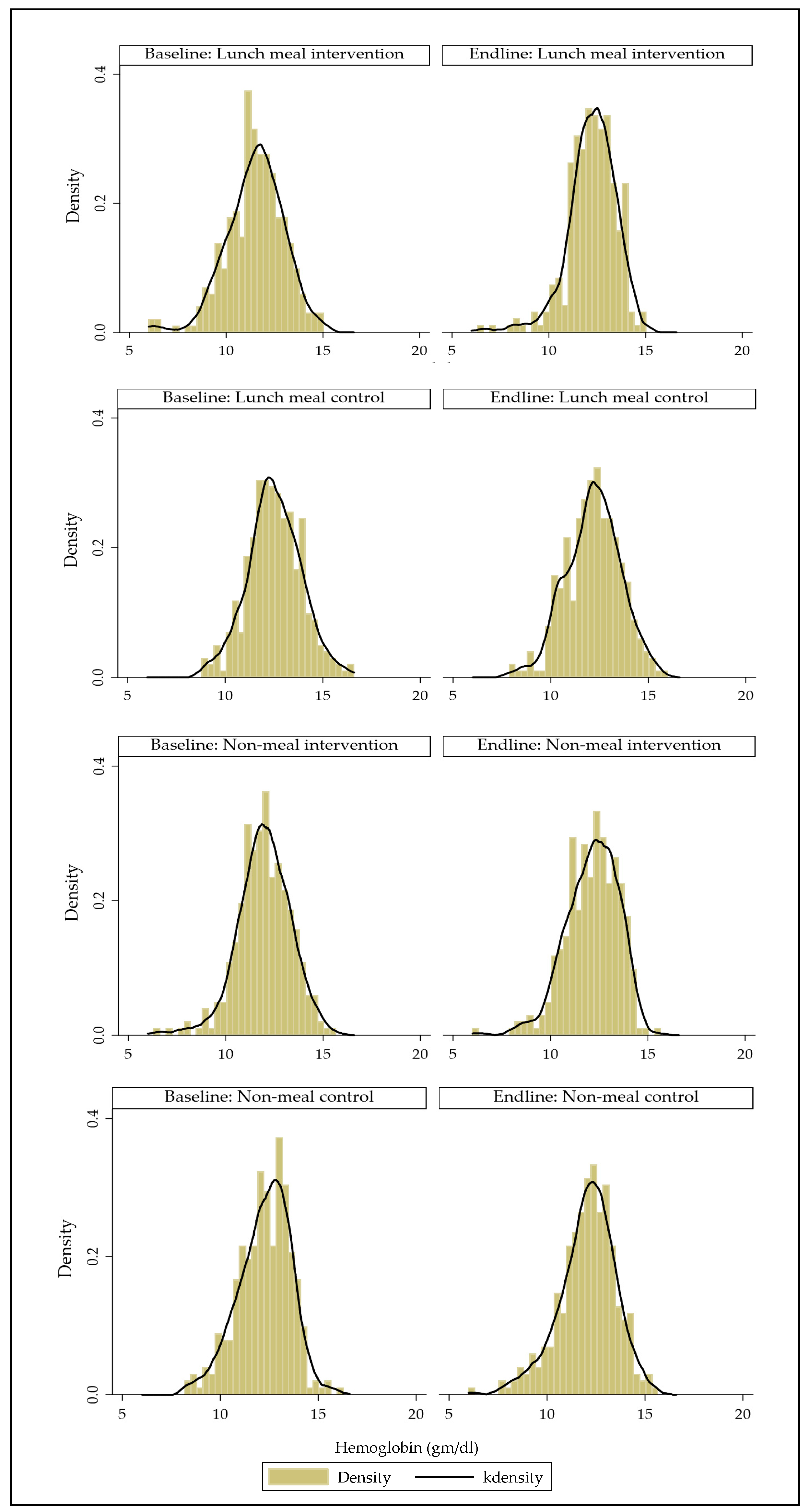

3.6. Change in Hemoglobin (gm/dL) and Weight (kg) Over Time

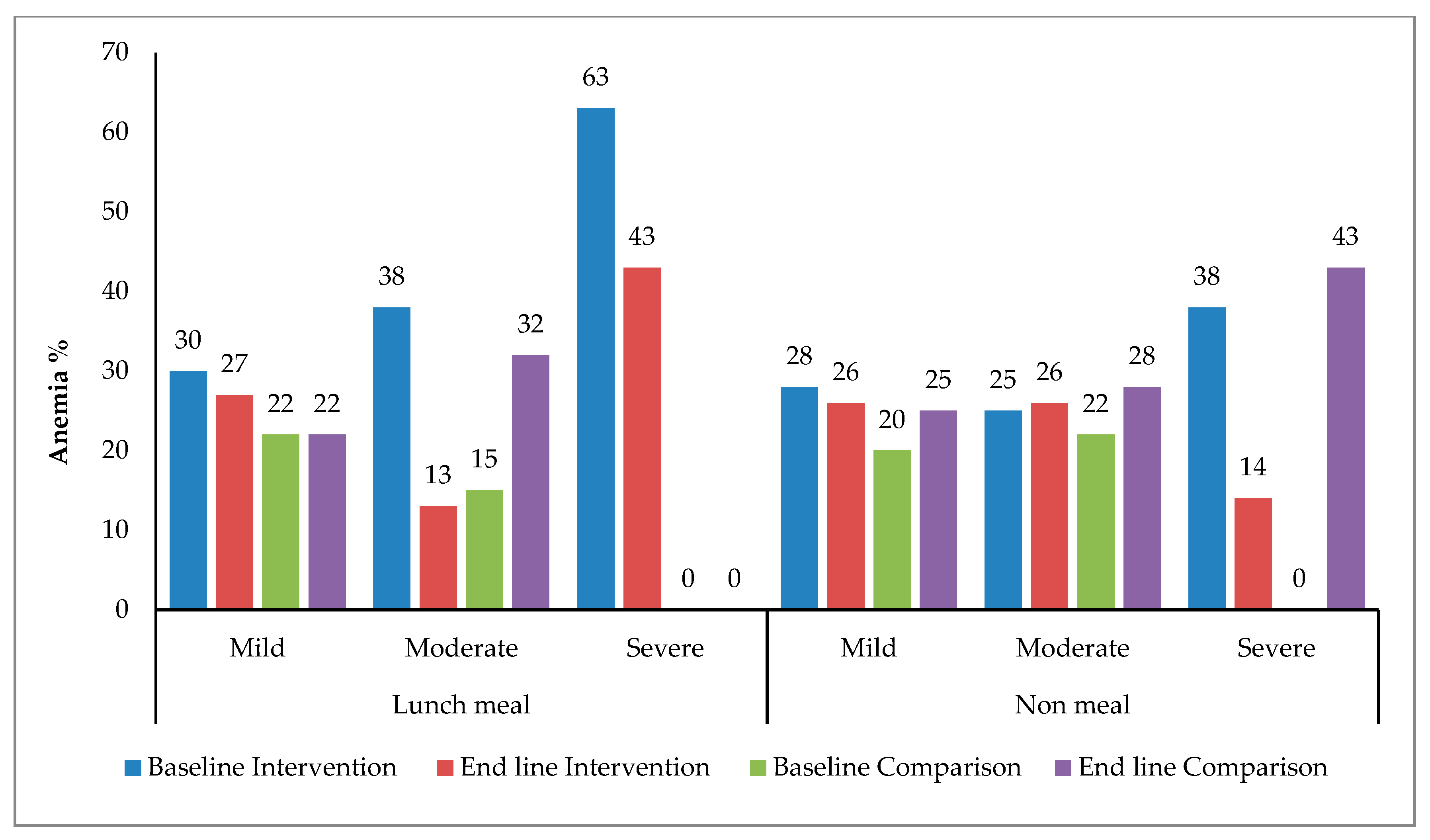

3.7. Changes in Anemia Prevalence, Hemoglobin Concentration and Anemia Severity over Time

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association: Toward a Sustainable Garment Industry (BGMEA). Trade Information. Available online: http://www.bgmea.com.bd/home/pages/TradeInformation (accessed on 23 September 2017).

- Hasnain, G.; Akter, M.; Sharafat, S.I.; Mahmuda, A. Morbidity patterns, nutritional status, and healthcare-seeking behavior of female garment workers in Bangladesh. Electron. Phys. 2014, 6, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, T.; Alamin, A.; Saleh, F.; Hossain, M.; Hoque, A.; Ali, L. Anemia among Garment Factory Workers in Bangladesh. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 16, 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, S.; Ross, J. The economics of iron deficiency. Food Policy 2003, 28, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Study. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014, 385, 117–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benoist, B.; McLean, E.; Egll, I.; Cogswell, M. Worldwide Prevalence of Anaemia 1993–2005: WHO Global Database on Anaemia; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherall, D.J.; Clegg, J.B. Inherited haemoglobin disorders: An increasing global health problem. Bull. World Health Organ. 2001, 79, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petry, N.; Olofin, I.; Hurrell, R.; Boy, E.; Wirth, J.; Moursi, M.; Donahue Angel, M.; Rohner, F. The Proportion of Anemia Associated with Iron Deficiency in Low, Medium, and High Human Development Index Countries: A Systematic Analysis of National Surveys. Nutrients 2016, 8, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perignon, M.; Fiorentino, M.; Kuong, K.; Dijkhuizen, M.A.; Burja, K.; Parker, M.; Chamnan, C.; Berger, J.; Wieringa, F.T. Impact of Multi-Micronutrient Fortified Rice on Hemoglobin, Iron and Vitamin A Status of Cambodian Schoolchildren: A Double-Blind Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, A.B.; Joffe, A.; Duggan, A.K.; Casella, J.F.; Brandt, J. Randomised study of cognitive effects of iron supplementation in non-anaemic iron-deficient adolescent girls. Lancet 1996, 348, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, C.; Porcayo, M.; Onofre, G.; Garcia-Guerra, A.; Elliott, T.; Jankowski, S.; Greiner, T. Efficacy of iron-fortified Ultra Rice in improving the iron status of women in Mexico. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.E.; Mosites, E.; Reider, K.; Ndayishimiye, N.; Waring, M.; Nyandimbane, G.; Masumbuko, D.; Ndikuriyo, L.; Matthias, D. A Blinded, Cluster-Randomized, Placebo-Controlled School FeedingTrial in Burundi Using Rice Fortified with Iron, Zinc, Thiamine, and Folic Acid. Food Nutr. Bull. 2015, 36, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Khanh, T.; Burja, K.; Thuy Nga, T.; Kong, K.; Berger, J.; Gardner, M.; Dijkhuizen, M.A.; Hop, L.T.; Tuyen, L.D.; Wieringa, F.T. Organoleptic qualities and acceptability of fortified rice in two Southeast Asian countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1324, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, K.; Liabsuetrakul, T.; Pradhan, N. Effect of education and pill count on hemoglobin status during prenatal care in Nepalese women: A randomized controlled trial. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2009, 35, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risonar, M.G.; Rayco-Solon, P.; Tengco, L.W.; Sarol, J.N., Jr.; Paulino, L.S.; Solon, F.S. Effectiveness of a redesigned iron supplementation delivery system for pregnant women in Negros Occidental, Philippines. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Girard, A.W.; Olude, O. Nutrition Education and Counselling Provided during Pregnancy: Effects on Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Outcomes. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2012, 26, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, M.B. Anemia and infection: A complex relationship. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia 2011, 33, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIRDEM. Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh; BIRDEM: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization; United Nations University. Human Energy Requirements: Report of a Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation, Rome, Italy, 17–24 October 2001; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Intermittent Iron and Folic Acid Supplementation in Menstruating Women; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, W.N.; Conti, D.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Schultz, A.B.; Edington, D.W. The role of health risk factors and disease on worker productivity. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 1999, 41, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, S.K.; Jhohura, F.T.; Khanam, F.; Akter, F.; Khan, S.; Yunus, F.M.; Hossain, M.B.; Afsana, K.; Haque, M.R.; Rahman, M. An outline of anemia among adolescent girls in Bangladesh: Findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Hematol. 2017, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity; Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System, World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Admin. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 20.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ara, G.; Khanam, M.; Rahman, A.S.; Islam, Z.; Farhad, S.; Sanin, K.I.; Khan, S.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Majoor, H.; Ahmed, T. Effectiveness of micronutrient-fortified rice consumption on anaemia and zinc status among vulnerable women in Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Kumar, R.; Bhutta, Z.A. Micronutrient fortification of food and its impact on woman and child health: A systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2013, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackl, L.S.; Abizari, A.R.; Speich, C.; Zungbey-Garti, H.; Cercamondi, C.I.; Zeder, C.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Moretti, D. Micronutrient-fortified rice can be a significant source of dietary bioavailable iron in schoolchildren from rural Ghana. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau0790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; El-Obeid, T. High iron intake is associated with poor cognition among Chinese old adults and varied by weight status-a 15-y longitudinal study in 4852 adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Zhen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Taylor, A.W. Hb level, iron intake and mortality in Chinese adults: A 10-year follow-up study. Br. J. Nutr. 2017, 117, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gaxiola, A.C.; De-Regil, L.M. Intermittent iron supplementation for reducing anaemia and its associated impairments in menstruating women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, G.J.; Montresor, A.; Cavalli-Sforza, L.T.; Thu, H.; Phu, L.B.; Tinh, T.T.; Tien, N.T.; Phuc, T.Q.; Biggs, B.-A. Elimination of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Soil Transmitted Helminth Infection: Evidence from a Fifty-four Month Iron-Folic Acid and De-worming Program. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, G.J.; Phuc, T.Q.; MacGregor, L.; Montresor, A.; Mihrshahi, S.; Thach, T.D.; Tien, N.T.; Biggs, B.-A. A free weekly iron-folic acid supplementation and regular deworming program is associated with improved hemoglobin and iron status indicators in Vietnamese women. BMC Public Health 2009, 9, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakoob, M.Y.; Bhutta, Z.A. Effect of routine iron supplementation with or without folic acid on anemia during pregnancy. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena-Rosas, J.P.; Viteri, F.E. Effects of routine oral iron supplementation with or without folic acid for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Khan, M.R.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Karim, R.; Marks, G.C.; Banu, C.P.; Nahar, B.; Williams, G. Efficacy of twice-weekly multiple micronutrient supplementation for improving the hemoglobin and micronutrient status of anemic adolescent schoolgirls in Bangladesh. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Gumashta, R. Weekly iron folate supplementation in adolescent girls—An effective nutritional measure for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 5, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.I.; Mahmud, A.A.; Bajracharya, A.; Rob, U.; Reichenbach, L. Evaluation of the HERhealth Intervention in Bangladesh: Baseline Findings from an Implementation Research Study, Situation Analysis Report; The Evidence Project: Washington, DC, USA; Population Council: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, R. Nicer Work? Impactt’s Benefits for Business and Workers Programme 2011–2013; Impactt: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hearle, C. Skills, Employment and Productivity in the Garments and Construction Sectors in Bangladesh and Elsewhere; Oxford Policy Management: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- icddr,b; UNICEF; GAIN; Institute of Public Health and Nutrition (IPHN). National Micronutrients Status Survey: 2011–2012; icddr,b: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2013.

- Straub, R.H. Systemic disease sequelae in chronic inflammatory diseases and chronic psychological stress: Comparison and pathophysiological model. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1318, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Rutherford, S.; Akhter Kumkum, F.; Bromwich, D.; Anwar, I.; Rahman, A.; Chu, C. Work, gender roles, and health: Neglected mental health issues among female workers in the ready-made garment industry in Bangladesh. Int. J. Women’s Health 2017, 9, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noben, C.; Hoefsmit, N.; Evers, S.; de Rijk, A.; Houkes, I.; Nijhuis, F. Economic Evaluation of a New Organizational RTW Intervention to Improve Cooperation Between Sick-Listed Employees and Their Supervisors: A Field Study. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiqul, I.M. Labor incentive and performance of the industrial firm: A case study of Bangladeshi RMG industry. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 7, 52–63. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, S. Opportunities for Investments in Nutrition in Low-income Asia. Asian Dev. Rev. 1999, 17, 246–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.S.; Raheem, E.; Sultana, T.A.; Ferdous, S.; Nahar, N.; Islam, S.; Arifuzzaman, M.; Razzaque, M.A.; Alam, R.; Aziz, S.; et al. Thalassemias in South Asia: Clinical lessons learnt from Bangladesh. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Package of Interventions for Factories with A Lunch Program | ||

| No. factories | 1 Control factory (B) | 1 Intervention factory (A) |

| Lunch | The factory provides the usual lunch meal with non-fortified rice and lentils and a small portion of single/mixed vegetable daily, meat or fish or egg three times weekly. The food was cooked with fortified oil and iodized salt. Rice and lentils were served daily in unlimited portions. | The factory provides a lunch meal enhanced with micronutrient fortified rice, as well as a diverse diet which includes animal sources foods 3 times per week, an egg at least one day per week, pulses and fortified rice and 1 larger portion of vegetable every day including a serving of green leafy vegetables 6 days per week. The food was cooked with fortified oil and iodized salt. Rice and lentils were served daily in unlimited portions. Lentils were made with twice the regular lunch lentil content per cooked volume. |

| Supplements | No IFA or other nutritional supplements | Once weekly IFA supplement to female factory workers; those reporting to be pregnant offered once daily supplements |

| BCC activities | Regular BCC modules include: Eating healthy Maternal health Reproductive health and family planning Sexually transmitted infections Malaria and Dengue Personal Hygiene Serious Illness Reproductive Cancer Waterborne Diseases Your body and menstruation | Enhanced BCC Module: regular BCC module in addition with: 1. Anemia 2. Nutrition and Dietary Diversity 3. Infant and Young Child Nutrition (IYCN) + Breastfeeding (BF) |

| Package of Interventions for factories without a lunch program | ||

| No. factories | 1 Control factory (D) | 1 Intervention factory (C) |

| Supplements | No IFA or other nutritional supplements provided to workers through the factory | Factory provided twice weekly IFA supplement to female factory workers; those reporting to be pregnant was offered once daily supplements |

| BCCactivities | Regular BCC module (Same modules as described above) | Enhanced BCC Module (Same modules as described above) |

| Variables | Lunch Meal | Non-Meal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n = 326) | C (n = 328) | p | I (n = 328) | C (n = 328) | p | |

| n (%) | Factory A | Factory B | Factory C | Factory D | ||

| Age in years | ||||||

| 18–22 | 60 (18.4) | 47 (14.3) | NS | 40 (12.2) | 29 (8.8) | NS |

| 23–27 | 110 (33.7) | 127 (38.7) | 109 (33.2) | 88 (26.8) | ||

| 28–32 | 100 (30.7) | 101 (30.8) | 109 (33.2) | 129 (39.3) | ||

| 33–37 | 36 (11.0) | 41 (12.5) | 56 (17.1) | 63 (19.2) | ||

| 38–42 | 20 (6.1) | 12 (3.7) | 14 (4.3) | 19 (5.8) | ||

| Worker type | ||||||

| Fresher/trainee | 14 (4) | 12 (3.7) | NS | 29 (8.8) | 17 (5.2) | NS |

| Permanent | 312 (95.7) | 316 (96.3) | 299 (91.2) | 311 (94.8) | ||

| Religion | ||||||

| Islam | 316 (96.9) | 317 (96.6) | NS | 291 (88.7) | 306 (93.3) | NS |

| Hindu | 10 (3.1) | 10 (3.0) | 35 (10.7) | 22 (6.7) | ||

| Christian | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 238 (73.0) | 259 (79) | 0.004 | 264 (80.5) | 281 (85.7) | 0.005 |

| Unmarried | 58 (17.8) | 30 (9.1) | 36 (10.9) | 14 (4.3) | ||

| Divorced/separated/widow | 30 (9.2) | 39 (11.9) | 28 (8.5) | 33 (10.1) | ||

| Household ownership | ||||||

| Own house | 9 (2.8) | 165 (50.3) | <0.001 | 8 (2.4) | 14 (4.3) | NS |

| Rented house | 317 (97.2) | 163 (49.7) | 320 (97.6) | 314 (95.7) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Formal education | 286 (87.7) | 297 (90.5) | NS | 260 (79.3) | 278 (84.8) | NS |

| Asset quintile | ||||||

| Poorest | 61 (19) | 93 (28) | <0.001 | 83 (25.3) | 81 (24.7) | NS |

| Poorer | 58 (18) | 86 (26) | 91 (27.7) | 71 (21.7) | ||

| Middle | 63 (19) | 61 (19) | 63 (19.2) | 83 (25.3) | ||

| Richer | 59 (18) | 58 (18) | 62 (18.9) | 57 (17.4) | ||

| Richest | 85 (26) | 30 (9) | 29 (8.8) | 36 (11.0) | ||

| Works at overtime, n (%) | 316 (97) | 323 (98) | 0.018 | 309 (94) | 325 (99) | 0.001 |

| Hours of overtime per months, mean (SD) | 33 (10) | 41 (9) | <0.001 | 44 (19) | 47 (12) | 0.02 |

| Total Income in USD, median (IQR) | 100 (87.5, 108.8) | 108 (100, 112.7) | <0.001 | 104 (91.2, 117.7) | 108.8 (97.5, 116.3) | 0.006 |

| Total Expenditure in USD, median (IQR) | 93.8 (84.6, 106.3) | 100 (87.5, 114.4) | 0.001 | 101.3 (87.5, 112.5) | 106.3 (82.5, 112.5) | NS |

| Anemia, n (%) | 198 (60.7) | 109 (33.2) | <0.001 | 157 (47.9) | 119 (36.3) | 0.002 |

| Variables | Lunch Meal | Non-Meal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | |

| I (326) | I (306) | C (328) | C (328) | I (328) | I (328) | C (328) | C (328) | |||||

| Knowledge on: | Factory A | Factory B | Factory C | Factory D | ||||||||

| Main food groups | 27 (8.3) | 178 (58.2) | <0.001 | 43 (13.1) | 193 (58.8) | <0.001 | 26 (7.9) | 151 (46) | <0.001 | 23 (7.0) | 137 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| Vitamins and minerals | 52 (16.0) | 202 (66) | <0.001 | 69 (21.0) | 221 (67.4) | <0.001 | 41 (12.5) | 147 (44.8) | <0.001 | 36 (11.0) | 137 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| Benefits of vitamin A containing foods | 282 (86.5) | 299 (97.7) | <0.001 | 254 (77.4) | 312 (95.1) | <0.001 | 243 (74.1) | 308 (93.9) | <0.001 | 234 (71.3) | 311 (94.8) | <0.001 |

| Iron containing foods | 63 (19.3) | 232 (75.8) | <0.001 | 62 (18.9) | 184 (56.1) | <0.001 | 39 (11.9) | 181 (55.2) | <0.001 | 48 (14.6) | 146 (44.5) | <0.001 |

| Benefits of Iron containing foods | 245 (75.2) | 295 (96.4) | <0.001 | 236 (71.9) | 308 (93.9) | <0.001 | 218 (66.5) | 297 (90.6) | <0.001 | 220 (67.1) | 289 (88.1) | <0.001 |

| Availability of Vitamin A fortified oil | 55 (16.8) | 133 (43.5) | <0.001 | 85 (25.9) | 162 (49.4) | <0.001 | 68 (20.7) | 135 (41.2) | <0.001 | 58 (17.7) | 137 (41.8) | <0.001 |

| Variables | Lunch Meal | Non-Meal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | |

| I (326) | I (306) | C (328) | C (328) | I (328) | I (328) | C (328) | C (328) | |||||

| Factory A | Factory B | Factory C | Factory D | |||||||||

| Availability of clean and safe drinking water at workplace | 301 (92.3) | 280 (91.5) | <0.001 | 320 (97.6) | 327 (99.7) | 0.03 | 311 (94.8) | 322 (98.2) | 0.03 | 311 (94.8) | 319 (97.3) | NS |

| Reported hand washing after defecation | 311 (95.4) | 299 (97.7) | NS | 328 (100) | 326 (99.4) | NS | 327 (99.7) | 325 (99.1) | NS | 311 (94.8) | 322 (98.2) | 0.03 |

| Products used for menstrual hygiene management, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Sanitary pad | 88 (26.9) | 136 (44.4) | <0.001 | 135 (41.2) | 293 (46.2) | NS | 98 (29.9) | 151 (46) | <0.001 | 66 (20.1) | 103 (31.4) | 0.006 |

| Cloth | 231 (70.9) | 159 (52) | 184 (56.1) | 317 (50) | 210 (64.0) | 160 (48.8) | 233 (71.0) | 199 (60.7) | ||||

| Factory rags | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.6) | 7 (2.1) | 15 (2.4) | 8 (2.4) | 6 (1.8) | 11 (3.4) | 6 (1.8) | ||||

| Self-reported sickness in last 15 days, n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Diarrhea | 12 (3.7) | 10 (3.3) | NS | 8 (2.4) | 16 (2.5) | NS | 6 (1.8) | 8 (2.4) | NS | 5 (1.5) | 15 (4.6) | 0.02 |

| Dysentery | 5 (1.5) | 4 (1.3) | NS | 2 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | NS | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | NS | 6 (1.8) | 2 (0.6) | NS |

| Fever | 54 (16.6) | 36 (11.8) | NS | 70 (21.3) | 69 (10.9) | <0.001 | 66 (20.1) | 67 (20.4) | NS | 51 (15.6) | 55 (16.8) | NS |

| Common cold | 104 (31.9) | 70 (22.9) | <0.001 | 84 (25.6) | 128 (20.2) | <0.001 | 88 (26.8) | 83 (25.3) | NS | 67 (20.4) | 78 (23.8) | NS |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (7.4) | 8 (2.6) | <0.001 | 18 (5.5) | 15 (2.4) | <0.04 | 16 (4.9) | 19 (5.8) | NS | 11 (3.4) | 12 (3.7) | NS |

| Joint pain | 67 (20.6) | 43 (14.1) | 0.03 | 74 (22.6) | 84 (13.3) | <0.001 | 82 (25) | 87 (26.5) | NS | 60 (18.3) | 59 (18) | NS |

| Workplace absenteeism (in last 30 days preceding interview), n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Absence due to sickness | 22 (6.8) | 11 (3.6) | NS | 24 (7.3) | 21 (6.5) | NS | 32 (9.8) | 32 (9.8) | NS | 13 (3.9) | 24 (7.3) | 0.02 |

| Days of sickness absenteeism, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | NS | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | NS | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (2, 5) | NS | 2 (1, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | NS |

| Variables | Lunch meAl | Non-Meal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | Baseline | Endline | p | |

| I (326) | I (306) | C (328) | C (328) | I (328) | I (328) | C (328) | C (328) | |||||

| Factory A | Factory B | Factory C | Factory D | |||||||||

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL), mean (SD) | 11.5 (1.5) | 12.2 (1.2) | <0.001 | 12.5 (1.4) | 12.1 (1.3) | 0.001 | 11.9 (1.3) | 12.1 (1.3) | NS | 12.3 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.4) | 0.04 |

| Weight in kg, mean (SD) | 52.2 (8.8) | 53.5 (8.9) | NS | 51.3 (8.1) | 53.1 (8.5) | <0.01 | 52.0 (9.3) | 52.9 (9.5) | NS | 52.8 (8.6) | 54.3 (8.8) | 0.03 |

| Indicator | I before (i) | I after (ii) | Difference in I (ii–i) | C before (iii) | C after (iv) | Differece in C (iv–iii) | Baseline difference, (B = i–iii) | Endline difference, (E = ii–iv) | Unadjusted difference-in-difference (DID) (E–B) | Adjusted DID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia (%) | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Lunch meal (A vs. B) | 60.7 | 36.9 | −23.8 ** | 33.2 | 41.2 | 8.0 | 27.5 ** | −4.3 | −31.8 ** | −32.4 ** |

| Model 2 | Non-meal (C vs. D) | 47.9 | 41.5 | −5.5 | 36.3 | 41.8 | 6.4 | 11.6 | −0.3 | −11.9 * | −11.6b * |

| Hemoglobim (gm/dL) | |||||||||||

| Model 1 | Lunch meal (A vs. B) | 11.50 | 12.23 | 0.73 | 12.53 | 12.17 | −0.36 | −1.03 ** | 0.05 | 1.08 ** | 1.05 ** |

| Model 2 | Non-meal (C vs. D) | 11.98 | 12.14 | 0.16 | 12.27 | 12.05 | −0.22 | −0.29 ** | 0.10 | 0.39 ** | 0.40 ** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hossain, M.; Islam, Z.; Sultana, S.; Rahman, A.S.; Hotz, C.; Haque, M.A.; Dhillon, C.N.; Khondker, R.; Neufeld, L.M.; Ahmed, T. Effectiveness of Workplace Nutrition Programs on Anemia Status among Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh: A Program Evaluation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061259

Hossain M, Islam Z, Sultana S, Rahman AS, Hotz C, Haque MA, Dhillon CN, Khondker R, Neufeld LM, Ahmed T. Effectiveness of Workplace Nutrition Programs on Anemia Status among Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh: A Program Evaluation. Nutrients. 2019; 11(6):1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061259

Chicago/Turabian StyleHossain, Muttaquina, Ziaul Islam, Sabiha Sultana, Ahmed Shafiqur Rahman, Christine Hotz, Md. Ahshanul Haque, Christina Nyhus Dhillon, Rudaba Khondker, Lynnette M. Neufeld, and Tahmeed Ahmed. 2019. "Effectiveness of Workplace Nutrition Programs on Anemia Status among Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh: A Program Evaluation" Nutrients 11, no. 6: 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061259

APA StyleHossain, M., Islam, Z., Sultana, S., Rahman, A. S., Hotz, C., Haque, M. A., Dhillon, C. N., Khondker, R., Neufeld, L. M., & Ahmed, T. (2019). Effectiveness of Workplace Nutrition Programs on Anemia Status among Female Readymade Garment Workers in Bangladesh: A Program Evaluation. Nutrients, 11(6), 1259. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061259