Abstract

Patients affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) experience a huge cardiovascular risk and cardiovascular events represent the leading causes of death. Since traditional risk factors cannot fully explain such increased cardiovascular risk, interest in non-traditional risk factors, such as hyperhomocysteinemia and folic acid and vitamin B12 metabolism impairment, is growing. Although elevated homocysteine blood levels are often seen in patients with CKD and ESRD, whether hyperhomocysteinemia represents a reliable cardiovascular and mortality risk marker or a therapeutic target in this population is still unclear. In addition, folic acid and vitamin B12 could not only be mere cofactors in the homocysteine metabolism; they may have a direct action in determining tissue damage and cardiovascular risk. The purpose of this review was to highlight homocysteine, folic acid and vitamin B12 metabolism impairment in CKD and ESRD and to summarize available evidences on hyperhomocysteinemia, folic acid and vitamin B12 as cardiovascular risk markers, therapeutic target and risk factors for CKD progression.

1. Introduction

Patients affected by chronic kidney disease (CKD) or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have a shorter life expectancy than those with normal renal function, primarily due to the dramatic increase in cardiovascular mortality [1]. Chronic hemodialysis treatment is associated with a 10 to 50-fold higher risk of premature death than in the general population, and cardiovascular disease (CVD) represents the leading cause of death in hemodialysis patients [2,3]. Nevertheless, such increased cardiovascular risk is present since earlier stages of CKD [4].

In randomized clinical trials (RCTs), the traditional Framingham factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus have been proven to be poor predictors of cardiovascular risk in this population. Therefore, there has been growing attention on non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors, in particular oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, vascular calcification Chronic Kidney Disease—Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) and hyperhomocysteinemia [5].

The “homocysteine hypothesis” arises from the observation that subjects with very high homocysteine blood levels due to congenital homocysteine metabolism impairment are more susceptible to develop a severe form of progressing atherosclerosis. Thus, over the years, research has been conducted into the possible link between an even moderate rise in homocysteine levels and cardiovascular risk and mortality, with conflicting results [6,7].

Although patients with CKD and ESRD display elevated homocysteine levels, the role of hyperhomocysteinemia as a cardiovascular and mortality risk factor in this population is still to be fully elucidated and deserves further investigation [8,9,10,11,12].

Furthermore, the high prevalence of hyperhomocysteinemia in patients with CKD has increased interest in speculating the role for hyperhomocysteinemia as a risk factor for the progression of CKD [13,14].

The role of folic acid and vitamin B12 role is well recognized, as they are not only essential cofactors for homocysteine metabolism, but their homeostasis disruption may be related directly to cardiovascular risk and CKD progression [11,15].

The aim of this review was to summarize folic acid, vitamin B12 and homocysteine metabolism in CKD patients and to analyze the published evidences on folic acid and vitamin B12 deficiency as cardiovascular risk markers and therapeutic targets in CKD and ESRD patients.

2. B Vitamins—Homocysteine Pathway

B vitamins, including vitamin B9 (folate) and vitamin B12 (cobalamin) are water-soluble vitamins involved in several normal cellular functions: they are providers of carbon residues for purine and pyrimidine synthesis, nucleoprotein synthesis and maintenance in erythropoiesis [16].

Folic acid is derived from polyglutamates that are converted into monoglutamates in the bowel, and then transported across mucosal epithelia by a specific carrier. The circulating form of folic acid is 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) [17].

Vitamin B12, ingested with nutrients such as cobalamin, complexes with salivary haptocorrin, and is released abruptly from cobalamin by pancreatic proteases in the duodenum. Then, cobalamin, binds to an intrinsic factor secreted from the parietal cells of the stomach: when this complex arrives at the distal ileum, it is endocytosed from the enterocytes through cubilin. Then, cobalamin is carried into the plasma by a plasma transport protein named transcobalamin [16]. B12 is filtered by the glomerulus; however urine excretion is minimal due to reabsorption in the proximal tubule.

In target tissues, cobalamin is metabolized into two active forms: adenosylcobalamin in the mitochondria and methylcobalamin in the cytosol. Methylcobalamin is a methyl-transferring cofactor to the enzyme methionine synthase allowing homocysteine remethylation to methionine [17].

Homocysteine is a thiol-containing amino acid, not involved in protein synthesis, deriving from methionine metabolism. Plasma levels of homocysteine depend on several factors, such as genetic alteration of methionine metabolism enzymes or deficiency of vitamin B12, vitamin B6 or folic acid [18].

Methionine is transformed into S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) and then converted in S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) through a reaction catalyzed by methionine synthase reductase (MTRR). SAM, one of the most important methyl group donors, is formed within mitochondria and is a cofactor for a mutase known as methylmalonyl-CoA-mutase. This enzyme converts methylmalonyl-CoA into succinyl CoA, representing a crucial step in the catabolism of various amino acids and fatty acids. These processes also require pyridoxine (vitamin B6) as a cofactor [18].

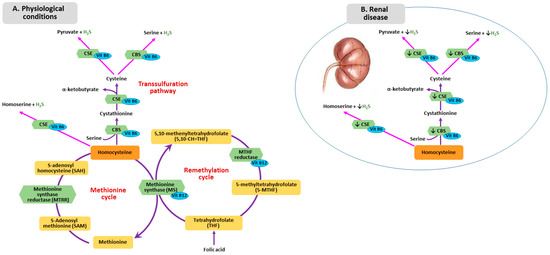

Homocysteine is the final product derived from hydrolysis of SAH to homocysteine and adenosine. Metabolism of homocysteine includes two different pathways: remethylation and transsulfuration (Figure 1A). In the remethylation pathway, methionine is regenerated through a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme methionine synthase (MTS), requiring folate and vitamin B12 as cofactors. Given that folate is not biologically active, it necessitates transformation into tetrahydrofolate that is then converted into methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHF) by the enzyme methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) [19].

Figure 1.

Homocysteine Metabolism in physiological condition (A) and in renal disease (B). CSE: cystathionine gamma-lyase; CBS: cystathionine beta synthase.

The other pathway responsible for the homocysteine metabolism is transsulfuration. First, homocysteine combines with serine forming cystathionine by cystathionine beta synthase (CBS), then, cystathionine is hydrolyzed into cysteine and α-ketobutyrate by cystathionine γ-lyase (CTH) Human CBS is expressed in the liver, kidneys, muscle brain and ovary, and during early embryogenesis in the neural and cardiac systems [20].

The sulfur atom, in the form of sulfane sulfur or hydrogen sulfide (H2S), can be involved in vitamin B12-dependent methyl group transfer [21,22]. Alterations in methylation pathway, which causes a reduction of proteins and DNA methylation, results in abnormal vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and increased lipid peroxidation [23]. Sulfur is a side product of conversion of homocysteine to cysteine by the enzymes CBS and cystathionine gamma-lyase (CSE). H2S is an angiogenic agent with antioxidant and vasorelaxing properties. Moreover, H2S represents an endogenous gaseous mediator, similarly to nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide [24], which plays a role in several physiological processes, namely vascular smooth muscle relaxation, inhibition of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and blood pressure lowering [25]. Li et al. proved that H2S metabolism impairment might contribute to the development of uremia-associated accelerated atherosclerosis in CKD patients with diabetic nephropathy [26]. Patients with CKD and ESRD show lower H2S plasma levels, which can result from downregulation of CBS and CSE, mediated by hyperhomocysteinemia (Figure 1B). Whether this phenomenon can be attributed to additional factors is still unclear [21].

Homocysteine can be found in reduced and oxidized form in the bloodstream: more than 90% of the total plasma homocysteine is oxidized and bound to proteins, while the remaining oxidized homocysteine exists as a disulfide form. Only 2% of the total homocysteine in plasma is present as a free reduced form [27].

Normal homocysteine plasmatic level is <10 mmol/L, concentrations >10; however, levels <16 mmol/L are defined as mild hyperhomocysteinemia, while severe hyperhomocysteinemia is diagnosed when homocysteine >100 mmol/L [28].

Homocysteine is minimally eliminated by the kidney, since in physiological conditions, only non-protein bound homocysteine is subjected to glomerular filtration, and then for most part reabsorbed in the tubuli and oxidized to carbon dioxide and sulfate in the kidney cells [25].

Moreover, in the kidney, homocysteine is above all transsulfurated and deficiency of this renal transsulfuration contributes to the elevation of plasma homocysteine [18].

3. Metabolism of Homocysteine, Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 in CKD

Patients with CKD and ESRD have been shown to have higher homocysteine blood levels compared to the general population [8,29]. It has been hypothesized that hyperhomocysteinemia in these patients may be induced by the abnormality of homocysteine metabolism in the kidneys rather than by reduced glomerular filtration rate. In fact, although free homocysteine can pass the ultrafiltration barrier due to its low molecular weight, it circulates in the bloodstream mostly (about 90%) in the protein-bound form [27]. In particular, transsulfuration and remethylation pathways occurring in the kidney may be affected by renal disease. Stable isotope studies in nondiabetic and diabetic patients with CKD have shown impaired metabolic clearance of homocysteine determined by dysfunction in both pathways [30].

In both CKD and ESRD patients, several metabolic alterations, including acidosis, systemic inflammation and hormonal dysregulation, together with comorbidities and multidrug therapies, can lead to malnutrition with subsequent folic acid and vitamin B12 deficiency. In addition, anorexia, gastroparesis, slow intestinal transit or diarrhea, increased gut mucosal permeability and gut microbiota impairment may represent worsening factors [31,32].

Folic acid metabolism is impaired in uremic patients. Organic and inorganic anions, whose clearance is reduced in CKD, inhibit the membrane transport of 5-MTHF, thus compromising the incorporation into nucleic acids and proteins. Data suggest that transport of folates is slower in uremia and this implicated that, even with normal plasmatic folate levels, the uptake rate of folates into tissues may be altered [33]. In fact, serum folate concentration does not represent a reliable measure of tissue folate stores, but rather reflects recent dietary intake of the vitamin. Erythrocyte folate concentration is a better indicator of whole folate status. In a population of 112 dialysis patients, Bamonti et al. found serum folate levels normal in only 37% of cases, despite over 80% of red blood cells folate levels within the normal range [34].

Regarding vitamin B12, several studies have shown a correlation between low serum vitamin B12 concentrations and high BMI, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia and CVD [35]. Vitamin B12 in the blood is primarily protein-bound. Approximately 20% of circulating B12 is bound to transcobalamin: this is the biologically active form that can be taken up into cells. Although CKD patients display increased transcobalamin levels, they show an impaired vitamin tissue uptake of B12 [36]. Moreover, in uremic patients a functional vitamin B12 deficiency can be observed because of increased transcobalamin losses in the urine and reduced absorption in the proximal tubule. This can lead to a “paradoxical” increase in cellular homocysteine levels despite normal total B12 [37].

On the other hand, potentially overdosage-related vitamin B12 toxicity could result exacerbated in individuals with CKD. Cyanocobalamin, the most commonly used form of B12 supplementation therapy, is indeed metabolized to active methylcobalamin, releasing small amounts of cyanide whose clearance is reduced in CKD [34]. Under normal conditions, methylcobalamin is required to remove cyanide from the circulation through conversion to cyanocobalamin. However, in CKD patients, the reduced cyanide clearance prevents conversion of cyanocobalamin to the active form and therefore supplementation is less effective [38].

The appropriate range of B12 levels in CKD remains to be defined adequately. Downstream metabolites, such as methylmalonic acid and homocysteine, may more accurately reflect functional B12 status in uremic patients [35].

4. Homocysteine-Mediated Tissue Damage

The pathogenic role of hyperhomocysteinemia on cardiovascular system in CKD and ESRD is related to atherosclerosis progression in the context of an already enhanced risk of vascular damage determined by uremic syndrome. One possible mechanism is the induction of local oxidative stress, generating Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) because of the thiol group, which rapidly undergoes autoxidation in the presence of oxygen and metal ion. Besides, hyperhomocysteinemia promotes Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity with further increase in ROS generation. Hyperhomocysteinemia also determines Nitric Oxide (NO) metabolism impairment in endothelial cells (including Nitric Oxide Synthase expression, localization, activation, and activity) leading, together with ROS-induced local microinflammation, to endothelial dysfunction [39].

In cultured endothelial cells, hyperhomocysteinemia has been shown to upregulate monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) production, resulting in monocyte adhesion to the endothelium [40]. The link between homocysteine and inflammatory factors seems to be the activated transcription factor NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells) [41].

Additionally, hyperhomocysteinemia induces vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) proliferation by promoting the expression of adhesion molecules, chemokine and VSMC mitogen leading to several interactions with platelets, clotting factors and lipids [42], and might contribute to the scavenger receptor-mediated uptake of oxidized- Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL) by macrophages, triggering foam cell formation in atherosclerotic plaque [43,44,45,46]. Hyperhomocysteinemia also determines a vascular remodeling process that involves activation of metalloproteinase and induction of collagen synthesis, with subsequent reduction of vascular elasticity [47].

Likewise, elevated blood levels of homocysteine can cause endothelial reticulum stress with increase endothelial apoptosis and inflammation through a process mediated by ROS production and NF-κB activation [48,49,50]. Endothelial cells are known to be particularly vulnerable to hyperhomocysteinemia, since they do not express CBS, the first enzyme of the hepatic reverse transsulfuration pathway, or betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), which catalyzes the alternate remethylation pathway in the liver using betaine as a substrate [51].

Lastly, N-homocysteinylation of proteins is one process responsible for homocysteine toxicity, since it causes structural and functional loss. For LDL, homocysteinylation produces aggregation, accumulation of cholesterol and formation of foam-cells. Fibronectin is also involved in N-homocysteinylation: this reaction contributes to extracellular matrix remodeling, promoting the development of sclerotic processes [52].

Some peculiar effects of hyperhomocysteinemia on renal tissue have been described. Homocysteine can act directly on glomerular cells inducing sclerosis, and it can initiate renal injury by reducing plasma and tissue level of adenosine. Decreased plasma adenosine leads to enhanced proliferation of VSMC, accelerating sclerotic process in arteries and glomeruli. In a rat model of hyperhomocysteinemia induced by a folate-free diet, glomerular sclerosis, mesangial expansion, podocyte dysfunction and fibrosis occurred due to enhanced local oxidative stress. After treatment of the animals with apocynin, a NADPH oxidase inhibitor, glomerular injury was significantly attenuated [53].

5. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Impairment and Tissue Injury

Both folic acid and vitamin B12 have shown a potential direct relationship with cardiovascular outcomes with mechanism unrelated to homocysteine levels, although not clearly understood [54].

Folic acid improves endothelial function without lowering homocysteine, suggesting an alternative explanation for its effect on endothelial function that is possibly related to its anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic properties [55,56,57]. Experimental models revealed that folic acid can reduce endothelial dysfunction through the limitation of oxidative stress generation and the increasing of NO half-life [17]. 5-MTHF, the circulating form of folic acid, acutely improves NO-mediated endothelial function and decreases superoxide production. Moreover, 5-MTHF prevents oxidation of BH4 increasing enzymatic coupling of eNOS, enhancing NO production. Because 5-MTHF is a reduced form of folic acid that does not require conversion by dihydrofolate reductase, some direct effects may be attributable to redox mechanisms that are not seen when oral folic acid is used to increase plasma folate levels [58,59].

Doshi et al. investigated the direct effects of folic acid on endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) through Flow Mediated Dilatation (FMD) measurement before and after folic acid intake. FMD improved at 2 h in parallel with folic acid blood concentration, while homocysteine blood level did not change significantly. These data suggest that folic acid improves endothelial function in CAD acutely by a mechanism largely independent of homocysteine [60]. Other authors demonstrated that high-dose folic acid (5 mg/day) improves endothelial function in CAD patients with an action not related to homocysteine level [60,61,62,63]. We have previously reported that supplementation with 5-MTHF versus folic acid improved survival rate without differences in homocysteine levels [11]. Pan et al. recently showed that folic acid treatment can inhibit atherosclerosis progression through the reduction of VSMC dedifferentiation in high-fat-fed LDL receptor-deficient mice [64].

From the vitamin B12 side, patients with chronic inflammation, such as the hemodialysis population, display decreased production of transcobalamin II, due to impaired uptake of circulating B12 by peripheral tissues. This can determine increased synthesis of transcobalamins I and III that brings to further accumulation of B12 in blood [65,66,67,68]. Therefore, in the context of inflammatory syndromes, despite high vitamin B12 blood levels, there is a vitamin B12 deficiency in target tissues, potentially leading to hyperhomocysteinemia and increased cardiovascular risk [69].

Concerning anemia, unless CKD and ESRD patients show significant folate depletion, additional supplementation of folic acid does not appear to have a beneficial effect on erythropoiesis or on responsiveness to Recombinant Human Erythropoietin (rHuEPO) therapy. However, a diagnosis of folate deficiency should be considered in such patients when significant elevation in mean cell volume or hypersegmented polymorphonuclear leucocytes are found, especially in subjects with malnutrition, history of alcohol abuse, or in patients hyporesponsive to rHuEPO. Measurements of circulating serum folate do not necessarily mirror tissue folate stores, and red blood cell folate measures provide a more accurate picture. Low red blood cells folate concentrations in these patients suggest the need for folate supplementation [70].

In patients with CKD, folate and vitamin B12 deficiency may represent an influential factor in renal anemia and hyporesponsiveness to rHuEPO therapy. As such, the possibility and the requirement of a regular supplementation is still a matter of debate [71].

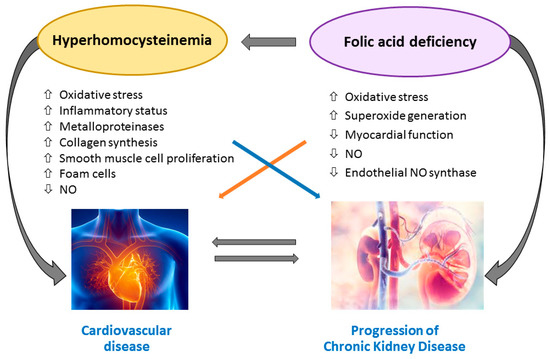

Figure 2 illustrates the pathways involved in the amplification of atherosclerosis and inflammation triggered by hyperhomocysteinemia in CKD patients.

Figure 2.

Hyperhomocysteinemia-induced amplification of atherosclerosis and inflammation in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Abbreviations: NO, Nitric Oxide.

6. MTHFR Gene Polymorphisms

MTHFR is an enzyme that plays a fundamental role in folate and homocysteine metabolism by catalyzing the conversion of 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate into 5-MTHF, the main circulating form of folate [72]. Several MTHFR gene polymorphisms have been described, and some of them seem to affect the individual susceptibility to a number of pathological conditions associated with homocysteine disorders, like myocardial infarction, stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune diseases, cancer, diabetes, birth defects and kidney disease [73].

The most characterized are four functional single nucleotide polymorphisms at position 677 (MTHFR 677 C > T), at position 1298 (MTHFR 1298 A > C), at position 1317 (MTHFR 1317 T > C) and at position 1793 (MTHFR 1793 G > A) [74].

Although some studies excluded an association between MTHFR 677 C > T genotype and long-term kidney outcomes [75], MTHFR 677 C > T polymorphism has been shown to contribute to increase cardiovascular risk in ESRD patients [76]. A study of 2015 by Trovato et al. on 630 Italian Caucasian subjects found a lower frequency of MTHFR 677 C > T and A1298 A > C polymorphisms among ESRD patients requiring hemodialysis, suggesting a protective role of these gene variants on renal function [77].

Despite the fact that the main function of the MTHFR enzyme is to regulate the availability of 5-MTHF for homocysteine remethylation, the pathological consequences of functional variants of MTHFR gene cannot only be attributed to the increase in homocysteine levels. While the homocysteine lowering effect of routine folate supplementation in general population has been proven, patients with ESRD seem to display a folate resistance even to higher doses of folate [78]. Folate and vitamin B12 supplementation effects on hemodialysis patients are controversial, and possibly dependent on MTHFR polymorphisms [79].

Anchour et al. recently evaluated folic acid response in terms of homocysteine lowering with respect to MTHFR polymorphism carrier status in a prospective cohort of 132 hemodialysis patients. The authors found that 677 C > T MTHFR genotype influences vitamin B supplementation response, as reported in previous studies [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86]. In particular, simultaneous supplementation of vitamin B12 and folate was useful only for the homozygous for the C allele, and the homocysteine reduction was significantly higher in carriers of TT genotype than in other genotypes [84].

Other authors reported that after B12 supplementation, homocysteine reduction in CC carriers was higher than in CT or TT carriers [82]. A renal substudy of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) evaluated the effects of the combination of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and folic acid with ACE inhibitors alone in reducing the risk of renal function decline in a hypertensive population without folic acid fortification. In 7545 patients treated with 10 mg enalapril and 0.8 mg folic acid, out of 15,104 participants, the greatest drop in serum homocysteine was in TT homozygotes of MTHFR 677 C > T polymorphism compared to other genotypes (CC/CT) [87].

In summary, the majority of available evidences suggest that MTHFR polymorphisms may influence folic acid and vitamin B12 treatment response in terms of homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with CKD and ESRD on dialysis although indication of routine testing is matter of debate [88].

7. Role of Folic Acid, Vitamin B12 and Homocysteine as Cardiovascular Risk Markers

Although hyperhomocysteinemia has been accepted for years as a cardiovascular risk factor, its association with CVD and mortality has been recently questioned and literature data are controversial [7,89,90]. Epidemiologic and case-control studies generally support an association of elevated plasma homocysteine levels with an increased incidence of CVD and stroke, whereas prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled studies do not [7].

Moreover, a discrepancy still exists about the indication of routine screening for hyperhomocysteinemia and its treatment in the general population [7].

For CKD and ESRD patients, in spite of the increased homocysteine levels (average homocysteine level in the general population about 10–15 mmol/L versus 25–35 mmol/L in uremic patients), the role of homocysteine as a cardiovascular and mortality risk factor is still uncertain and many retrospective and interventional studies resulted in conflicting evidences [8,9,10,11,12].

A meta-analysis including retrospective studies, prospective observational studies and interventional trials (total population 5123 patients) showed that elevated homocysteine blood levels represent a risk factor for both CVD and mortality in patients with ESRD not treated with folic acid supplementation [10].

The prospective studies included in the meta-analysis showed that in unsupplemented patients with ESRD, an increase of 5 mmol/L in homocysteine concentration is associated with an increase of 7% in the risk of total mortality and an increase of 9% in the risk of cardiovascular events [10]. Conversely, in a prospective cohort of 341 hemodialysis patients, we previously failed to demonstrate a relationship between baseline homocysteine as well as MTHFR polymorphisms and mortality [11].

At the origin of these divergences, several possible factors may be hypothesized, such as non-homogeneous populations selection, temporal discrepancies between competitive risk factors and influence of common complication including inflammation and protein-energy wasting (PEW) that could influence circulating homocysteine and that are associated with poorer outcomes [9].

An inverse correlation between homocysteine levels and cardiovascular outcomes in advanced CKD and in hemodialysis patients has also been documented, configuring the phenomenon known as “reverse epidemiology” that also involves other cardiovascular risk factors, including Body Mass Index (BMI), serum cholesterol and blood pressure [91]. Some evidence indeed suggests that the presence of PEW and inflammation may justify the observed reverse association between homocysteine and clinical outcome in CKD and ESRD patients [34,35,36,37]. Specifically, two studies showed that patients with very low homocysteine plasma levels had worse outcomes, as confirmed by a higher incidence of hospitalization and mortality [92,93].

These data call into question the reliability of homocysteine as a marker of cardiovascular risk and mortality in patients with CKD and ESRD, raising the suspicion that other mechanisms beyond elevated homocysteine levels might be implicated. Given that DNA methyltransferases are among the main targets of hyperhomocysteinemia, it has been hypothesized that epigenetic alterations could play a role in hyperhomocysteinemia-mediated tissue damage [12].

Sohoo et al. recently carried out a retrospective study on a large cohort of hemodialysis patients investigating the association between baseline folic acid and vitamin B12 levels and all-cause mortality after an observation period of 5 years (9517 patients for folic acid group and 12,968 patients for B12 group). The authors found that higher B12 concentrations (550 pg/mL) were associated with a higher risk of mortality after adjusting for sociodemographic and laboratory variables, while only lower serum folate concentrations (<6.2 ng/mL) were associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality. The authors pointed out that additional adjustment for malnutrition, inflammation and other clinical and laboratory variables nullified the folate–mortality association [15].

In our previous report, we demonstrated an improvement in survival rate of hemodialysis patients treated with 5-MTHF compared to folic acid, despite no difference in homocysteine levels between the two groups of treatment, raising the question whether 5-MTHF may have unique properties, unrelated to homocysteine lowering. Our finding of elevated CRP levels association with mortality allowed us to hypothesize that such effect may be mediated by a reduction in inflammation [11]. This raises the questions whether any benefit can be gained from lowering homocysteine and what role homocysteine actually plays in contributing towards cardiovascular events. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Retrospective and prospective observational studies on hyperhomocysteinemia and folic acid/vitamin B12 impairment in patients with CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

8. Effect of Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 Supplementation on CVD and Mortality in CKD and ESRD

Regarding folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation, the role such vitamins administration with the aim of reducing mortality and prevent progression to ESRD is still to be determined.

Moreover, effective folic acid and vitamin B12 supplementation dosages are not clearly established in the category of patients that take dosages ranging from 2.5 to 5 mg of folic acid three times a week up to more than 15 mg/day. Simultaneous administration of intravenous B complex vitamins is proven to be more efficient in reducing homocysteine serum levels and restoring the remethylation pathway in ESRD patients [116].

Righetti et al. in a one-year, placebo-controlled, non-blinded randomized control trial on a cohort of 81 chronic hemodialysis patients, showed no survival benefit of treatment with folic acid compared to placebo, and only 12% of patients on treatment reached normal homocysteine blood levels [117]. Wrone et al. found no difference in terms of mortality and cardiovascular events in a multicentre study on 510 patients on chronic dialysis randomized to 1, 5, or 15 mg/day of folic acid [76].

In the ASFAST study (Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in the Atherosclerosis and Folic Acid Supplementation Trial), a double blinded, placebo controlled trail, a randomized cohort of 315 CKD dialysis patients (with eGFR < 25 mL/min) were treated with folic acid 15 mg/die or placebo. After a median follow-up of 3.6 years, the results failed to demonstrate a benefit of folic acid therapy regarding all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and control of atheroma progression (carotid intima-media thickness progression) [118].

The HOST trial (Homocysteinemia in Kidney and End Stage Renal Disease) is a double blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 2056 patients with advanced CKD or ESRD requiring renal replacement therapy and elevated homocysteine levels, were randomized to a combined therapy with folic acid, vitamin B12 and piridoxin or placebo. After a median follow-up of 3.2 years, the study showed a significant reduction in homocysteine levels, but failed to reach its primary end-point, reduction of all-cause mortality, and its secondary end-point, reduction in cardiovascular death, amputation and thrombosis of the vascular access. A possible explanation for these negative results may be ascribed to the high cardiovascular comorbidity burden and the suboptimal compliance to therapy. Moreover, the study considered CKD and ESRD population together and was underpowered to evaluate the two populations separately. The disparity between these findings and the previously reported epidemiologic data could reflect limitations of observational studies [119].

Recently, Heinz et al. designed a multicenter trial on 650 chronic hemodialysis patients randomized to 5 mg folic acid, 50 µg vitamin B12 and 20 mg vitamin B6 versus placebo three times a week (post-dialysis) for 2 years. No differences were observed between the two groups in terms of all cause-mortality and fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events. On the other side, post-hoc analysis revealed a significant reduction in unstable angina pectoris and fewer vascularization procedures [120].

In a meta-analysis by Heinz et al. involving five intervention trials for a total of 1642 dialysis patients treated with folic acid, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6, a significant CVD risk reduction but not mortality risk reduction was demonstrated [10]. Another meta-analysis including 3886 patients with ESRD or advanced CKD (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) assessed the relationship between folic acid therapy (with or without vitamin B6 and B12) and CVD. Folic acid reduced cardiovascular risk by 15% in ESRD patients with greater benefit in those treated for longer than 24 months and in those from areas with no or partial grain fortification [121].

Ji et al. performed a large meta-analysis including 14 RCTs (54,913 participants) that demonstrated overall stroke events reduction resulting from homocysteine lowering following folic acid, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 supplementation. Beneficial effects in reducing stroke events were observed in the subgroup with CKD [122]. A meta-analysis of 10 studies concluded that homocysteine-lowering therapy is not associated with a significant decrease in the risks for CVD events, stroke, and all-cause mortality among patients with CKD. It has to be pointed out that, respect to previous meta-analysis a high number of participants with diabetes were included and that RCTs were performed in grain fortification areas [123]. More recently, a meta-analysis took into account six studies (comprising the abovementioned ones) for 2452 patients on chronic hemodialysis, finding no significant differences in mortality and in the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients treated with homocysteine lowering therapy [124].

Finally, many published post-hoc analyses have shown that several factors including age, baseline homocysteine levels, folic acid fortification of grains, B12 status, renal function, comorbidities and medications could be modifiers of folic acid and vitamin B12 effects on cardiovascular risk [12].

Table 2 summarizes the interventional studies investigating the effects of folic acid and vitamin B12 administration on CVD risk, mortality and CKD progression.

Table 2.

Interventional trials on the effects of folic acid and vitamin B12 administration and CVD risk, mortality and CKD progression.

To our knowledge, there are no published prospective studies that specifically addressed the effect of vitamin B12 alone on cardiovascular or renal outcomes in CKD and ESRD patients.

In summary, although the available trials indicate a reduction in homocysteine levels with medical therapy (folic acid, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6), in the majority of cases a benefit on mortality and on the incidence of cardiovascular events in patients with CKD and ESRD has not been demonstrated. Moreover, the beneficial effect could depend on anti-inflammatory and vascular protective effects.

9. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12: Evidences on CKD Progression

Regarding the relationship between folic acid, vitamin B12 supplementation and CKD progression, available interventional studies have demonstrated no clear benefit or even harmful effects on renal outcomes [15], while observational studies showed a correlation between hyperhomocysteinemia and risk of CKD development and progression [129].

The China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) is a large RCT (20,702 patients) that enrolled adults with hypertension without a history of stroke or myocardial infarction with determination of MTHFR genotype and baseline folate level. The study aimed at evaluating the effect of treatment with folic acid in an Asian population without folic acid fortification. Authors found that the ACE inhibitors plus folic acid therapy, compared with ACE inhibitors alone, reduced stroke risk. Moreover, subjects with the CC or CT MTHFR genotype had the highest risk of stroke and the greatest benefit of folic acid supplementation while those with the TT genotype required a higher dosage of folic acid to reach sufficient levels [80].

A renal sub-study of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT) compared the efficacy of combination of enalapril and folic acid with enalapril alone in reducing the risk of renal function decline in a large hypertensive population (15,104 patients). The study included patients with eGFR greater than 30 mL/min and participants were randomized to receive enalapril 10 mg plus folic acid 0.8 mg or enalapril 10 mg alone. Compared with the enalapril group, the enalapril-folic acid group showed reduced risk of CKD progression by 21% and a reduction of eGFR decline rate of 10% after a four-year follow-up. Authors performed a subgroup analysis that compared patients with CKD (defined as eGFR < 60 mL/min or presence of proteinuria) and without CKD at baseline. It resulted that CKD at baseline was a strong modifier of the treatment effect [85]. Specifically, the greatest decrease in serum homocysteine was in TT homozygotes of MTHFR 677 C > T polymorphism, while the magnitude of the declines in those with CC/CT genotypes was smaller. Finally, an exploratory subgroup analysis aimed to assess the treatment effect on the primary outcome in various subgroups among CKD participants showed that CKD progression risk reduction was more represented in diabetes subgroup [87]. This has been the first study showing renal protection from folic acid therapy in a population without folic acid fortification. Previous trials have reported a null or harmful effect of supplementation with folic acid and vitamin B12 [15,118].

In the abovementioned HOST study, treatment with high doses of folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12 failed to delay the time to initiating dialysis in patients with advanced CKD [15].

Diabetic Intervention with Vitamins to Improve Nephropathy (DIVINe) was a double blind RCT on a population of 238 patients with diabetic kidney disease randomized to receive 2.5 mg folic acid plus 25 mg vitamin B6 plus 1 mg vitamin B12, or placebo (mean eGFR was 64 mL/min in treatment group and 58 mL/min in the placebo group). Results showed that treatment with folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12 led to a greater decrease in GFR and to an increase in cardiovascular events compared to placebo after a follow-up of 2.6 years [125]. The possible explanations for such conflicting results may be multiple. First of all, baseline folic acid levels were different between studies (7.7 ng/mL for CSPPT renal sub study, 15 and 16.5 ng/mL for DIVINe and HOST study respectively) corroborating the hypothesis that beneficial effects of folic acid supplementation on renal outcomes could be stronger in patients with low folic acid level at baseline. In addition, vitamin B doses may play a role, as suggested by the elevated folate blood levels reached in the HOST study (2000 ng/mL) compared to CSPPT (23 ng/mL). This allowed postulating a potential toxicity determined by unmetabolized folic acid accumulated in the bloodstream [85]. Finally, CKD severity differed between the studies. In fact, the HOST study population was composed by patients with advanced CKD and with high comorbidity burden and this could have attenuated the study power with respect to renal outcomes. The fact that the CSPPT renal sub study demonstrated a benefit of folic acid therapy on the progression of renal damage could be related to the choice of a population with mild-moderate CKD. Furthermore, only CSPPT trial selected a population without folic acid grain fortification, while the other two studies were carried out in countries with folic acid fortification programs.

Besides, a recent study on 630 Italian Caucasian population found a lower frequency of MTHFR 677 C > T and A1298 A > C polymorphisms among dialysis patients compared to subjects without or with slight-moderate renal impairment, suggesting a protective role of both polymorphisms on renal function [39].

In conclusion, the available evidences regarding the effect of homocysteine lowering therapies on CKD progression are controversial and further studies with CKD progression as primary end-point and more homogeneous population selection are needed. While awaiting further evidences, it seems reasonable to treat patients with folic acid deficiency in order to reduce the risk of CKD progression avoiding accumulation phenomena that could lead to toxicity.

10. Folic Acid and Vitamin B12 in Kidney Transplant Recipients

In kidney transplant recipients several factors such as dialytic history, anemia, immunosuppression, inflammatory state and dysmetabolic alterations may influence cardiovascular risk [130].

A decline in homocysteine blood levels after kidney transplantation is frequently observed; nonetheless, hyperhomocysteinemia usually persists [131,132,133]. It has been documented that homocysteine can be further lowered among stable transplant recipients through high-dose B-vitamin therapy [134]. The effect of folic acid, vitamin B12 and vitamin B6 supplementation on cardiovascular risk and mortality reduction has been investigated by the Folic Acid for Vascular Outcome Reduction in Transplantation (FAVORIT) trial. Stable transplant recipients were randomized to daily multi-vitamin drug containing high-doses of folate (5.0 mg), vitamin B12 (1.0 mg) and vitamin B6 (50 mg) or placebo. The study was terminated early after an interim analysis because, despite effectively homocysteine lowering action, the incidence of CVD, all-cause mortality and onset of dialysis-dependent kidney failure did not differ between the treatment arms [135].

A longitudinal ancillary study of the FAVORIT trial recently showed that high-dose B-vitamin supplementation determined modest cognitive benefit in patients with elevated baseline. It has to be pointed out that almost all subjects had no folate or B12 deficiency; thus, the potential cognitive benefits of folate and B12 supplementation in individuals with poor B-vitamin status remains controversial [136].

11. Conclusions

At present, the available evidence does not provide full support to consider hyperhomocysteinemia, folic acid and vitamin B12 alterations reliable cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular mortality risk markers in CKD and ESRD populations. Furthermore, such factors do not represent a validated therapeutic target regarding the reduction of cardiovascular risk and CKD progression.

While waiting for the results of confirmatory trials, it seems reasonable to consider folic acid with or without vitamin B12 supplementation as appropriate adjunctive therapy in patients with CKD.

Concerning patients in early CKD stages for which potassium or phosphorus dietary intake restriction is not indicated, folic acid could come in the form of a healthy diet rich in natural sources of folate. For patients with advanced CKD and on dialysis, folic acid can be supplemented pharmacologically after accurate folate status assessment.

Author Contributions

I.C., G.C. and G.L.M.: design of the work and manuscript revision. L.G., F.Z. and F.T.: literature review, writing and manuscript preparation. M.C.: figure preparation and manuscript revision. All authors approve the submitted version, agree to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which an author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved and documented in the literature.

Funding

The authors declare no funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Go, A.S.; Chertow, G.M.; Fan, D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Hsu, C.Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1296–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, R.N.; Parfrey, P.S.; Sarnak, M.J. Epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998, 9, S16–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, V.; Garcia-Garcia, G.; Iseki, K.; Li, Z.; Naicker, S.; Plattner, B.; Saran, R.; Wang, A.Y.; Yang, C.W. Chronic kidney disease: Global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013, 382, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, P.A.; Steigerwalt, S.; Tolia, K.; Chen, S.C.; Li, S.; Norris, K.C.; Whaley-Connell, A.; KEEP Investigators. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: Data from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Curr. Diab. Rep. 2011, 11, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekdahl, K.; Soveri, I.; Hilborn, J.; Fellström, B.; Nilsson, B. Cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis: Role of the intravascular innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCully, K.S. Homocysteine and vascular disease. Nat. Med. 1996, 2, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysant, S.G.; Chrysant, G.S. The current status of homocysteine as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: A mini review. Expert. Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 16, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. Renal disease, homocysteine, and cardiovascular complications. Circulation 2004, 109, 294–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suliman, M.E.; Lindholm, B.; Barany, P.; Qureshi, A.R.; Stenvinkel, P. Homocysteine-lowering is not a primary target for cardiovascular disease prevention in chronic kidney disease patients. Semin. Dial. 2007, 20, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, J.; Kropf, S.; Luley, C.; Dierkes, J. Homocysteine as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in patients treated by dialysis: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 54, 478–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianciolo, G.; La Manna, G.; Colì, L.; Donati, G.; D’Addio, F.; Persici, E.; Comai, G.; Wratten, M.; Dormi, A.; Mantovani, V.; et al. 5-methyltetrahydrofolate administration is associated with prolonged survival and reduced inflammation in ESRD patients. Am. J. Nephrol. 2008, 28, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianciolo, G.; De Pascalis, A.; Di Lullo, L.; Ronco, C.; Zannini, C.; La Manna, G. Folic Acid and Homocysteine in Chronic Kidney Disease and Cardiovascular Disease Progression: Which Comes First? Cardiorenal. Med. 2017, 7, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti, F.; Vollenweider, P.; Marques-Vidal, P.M.; Mooser, V.; Waeber, G.; Paccaud, F.; Bochud, M. Hyperhomocysteinemia is independently associated with albuminuria in the population-based CoLaus study. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponte, B.; Pruijm, M.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Martin, P.Y.; Burnier, M.; Paccaud, F.; Waeber, G.; Vollenweider, P.; Bochud, M. Determinants and burden of chronic kidney disease in the population-based CoLaus study: A cross-sectional analysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2013, 28, 2329–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soohoo, M.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Qader, H.; Streja, E.; Obi, Y.; Moradi, H.; Rhee, C.M.; Kim, T.H.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Association of serum vitamin B12 and folate with mortality in incident hemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2017, 32, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.S.; Wong, P.W.K.; Malinow, M.R. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia as a risk factor for occlusive vascular disease. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1992, 12, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randaccio, L.; Geremia, S.; Demitri, N.; Wuerges, J. Vitamin B12: Unique metalorganic compounds and the most complex vitamins. Molecules 2010, 15, 3228–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Nie, J. Homocysteine in Renal Injury. Kidney Dis. 2016, 2, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Guldener, C.; Stam, F.; Stehouwer, C.D. Hyperhomocysteinaemia in chronic kidney disease: Focus on transmethylation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005, 43, 1026–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, D.W. Homocysteine and vitamins in cardiovascular disease. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Cianciolo, G.; Cappuccilli, M.; La Manna, G. The Hydrogen Sulfide-Vitamin B12-Folic Acid Axis: An Intriguing Issue in Chronic Kidney Disease. A Comment on Toohey JI: “Possible Involvement of Hydrosulfide in B12-Dependent Methyl Group Transfer”. Molecules 2017, 22, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toohey, J.I. Possible Involvement of Hydrosulfide in B12-Dependent Methyl Group Transfer. Molecules 2017, 22, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, G.N.; Loscalzo, J. Homocysteine and atherothrombosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1042–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R. Two’s company, three’s a crowd: Can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J. 2002, 16, 1792–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, A.F.; Sepe, I.; Lanza, D.; Capasso, R.; Di Marino, V.; De Santo, N.G.; Ingrosso, D. The gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide in hemodialysis patients. J. Nephrol. 2010, 23, S92–S96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Feng, S.J.; Zhang, G.Z.; Wang, S.X. Correlation of lower concentrations of hydrogen sulfide with atherosclerosis in chronic hemodialysis patients with diabetic nephropathy. Blood Purif. 2014, 38, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Guldener, C.; Stehouwer, C.D. Homocysteine metabolism in renal disease. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2003, 41, 1412–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, A.F.; Ingrosso, D.; Satta, E.; Lombardi, C.; Acanfora, F.; De Santo, N.G. Homocysteine metabolism in renal failure. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2004, 7, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, R.C.; Goodbred, A.J. Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Recognition and Management. Am. Fam. Physician 2017, 96, 384–389. [Google Scholar]

- Brattström, L.; Wilcken, D.E. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: Cause or effect? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Guldener, C.; Kulik, W.; Berger, R.; Dijkstra, D.A.; Jakobs, C.; Reijngoud, D.J.; Donker, A.J.; Stehouwer, C.D.; De Meer, K. Homocysteine and methionine metabolism in ESRD: A stable isotope study. Kidney Int. 1999, 56, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, Y.; Qian, Q. Protein Nutrition and Malnutrition in CKD and ESRD. Nutrients 2017, 27, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennette, J.C.; Goldman, I.D. Inhibition of the membrane transport of folate by anions retained in uremia. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1975, 86, 834–843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bamonti-Catena, F.; Buccianti, G.; Porcella, A.; Valenti, G.; Como, G.; Finazzi, S.; Maiolo, A.T. Folate measurements in patients on regular hemodialysis treatment. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 33, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, G.M.; Hwang, S.J.; Tanner, R.M.; Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J.; Muntner, P.; Fox, C.S. The association between vitamin B12, albuminuria and reduced kidney function: An observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermens, A.A.; Vlasveld, L.T.; Lindemans, J. Significance of elevated cobalamin (vitamin B12) levels in blood. Clin. Biochem. 2003, 36, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, E.; Serraj, K.; Zhu, J.; Vermorken, A.J. The pathophysiology of elevated vitamin B12 in clinical practice. QJM 2013, 106, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, K.; Yoshida, A.; Takeda, A.; Morozumi, K.; Fujinami, T.; Tanaka, N. Abnormal cyanide metabolism in uraemic patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1997, 12, 1622–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, R.; Sivasubramanian, N.; DiBello, P.M.; Robinson, K.; Jacobsen, D.W. Homocysteine induces expression and secretion of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and interleukin-8 in human aortic endothelial cells: Implications for vascular disease. Circulation 2001, 103, 2717–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, N.; Chen, J.; Gu, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, K. Role of Hyperhomocysteinemia and Hyperuricemia in Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2017, 26, 2695–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au-Yeung, K.K.; Woo, C.W.; Sung, F.L.; Yip, J.C.; Siow, Y.L.; O, K. Hyperhomocysteinemia activates nuclear factor-kappaB in endothelial cells via oxidative stress. Circ. Res. 2004, 94, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Lewis, A.; Brodsky, S.; Rieger, R.; Iden, C.; Goligorsky, M.S. Homocysteine induces 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase in vascular endothelial cells: A mechanism for development of atherosclerosis? Circulation 2002, 105, 1037–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecoits-Filho, R.; Lindholm, B.; Stenvinkel, P. The malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome – the heart of the matter. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2002, 17, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colì, L.; Donati, G.; Cappuccili, M.L.; Cianciolo, G.; Comai, G.; Cuna, V.; Carretta, E.; La Manna, G.; Stefoni, S. Role of the hemodialysis vascular access type in inflammation status and monocyte activation. Int. J. Art. Organs. 2011, 34, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, J.C.; Perrella, M.A.; Yoshizumi, M.; Hsieh, C.M.; Haber, E.; Schlegel, R.; Lee, M.E. Promotion of vascular smooth muscle cell growth by homocysteine: A link to atherosclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 6369–6373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiger, A.K.; Hurtig-Wennlof, A.; Sjostrom, M.; Yngve, A.; Nilsson, T.K. Association of total plasma homocysteine with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genotypes 677C>T, 1298A>C, and 1793G>A and the corresponding haplotypes in Swedish children and adolescents. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 19, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, U.; Mishra, P.K.; Tyagi, N.; Tyagi, S.C. Homocysteine to hydrogen sulfide or hypertension. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 57, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Cai, Y.; Adachi, M.T.; Oshiro, S.; Aso, T.; Kaufman, R.J.; Kitajima, S. Homocysteine induces programmed cell death in human vascular endothelial cells through activation of the unfolded protein response. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 35867–53874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baydas, G.; Reiter, R.J.; Akbulut, M.; Tuzcu, M.; Tamer, S. Melatonin inhibits neural apoptosis induced by homocysteine in hippocampus of rats via inhibition of cytochrome c translocation and caspase-3 activation and by regulating pro- and antiapoptotic protein levels. Neuroscience 2005, 135, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Kaufman, R. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature 2008, 454, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finkelstein, J.D. Methionine metabolism in mammals. J. Nutr. Biochem. 1990, 1, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, A.F.; Ingrosso, D.; Violetti, E.; Luciano, M.G.; Sepe, I.; Lanza, D.; Capasso, R.; Ascione, E.; Raiola, I.; Lombardi, C.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in uremia—A red flag in a disrupted circuit. Semin. Dial. 2009, 22, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deussen, A.; Pexa, A.; Loncar, R.; Stehr, S.N. Effects of homocysteine on vascular and tissue adenosine: A stake in homocysteine pathogenicity? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2005, 43, 1007–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solini, A.; Santini, E.; Ferrannini, E. Effect of short-term folic acid supplementation on insulin sensitivity and inflammatory markers in overweight subjects. Int. J. Obes. (Lond) 2006, 30, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Prasad, S.K.; Pal, S.; Maji, B.; Syamal, A.K.; Mukherjee, S. Synergistic protective effect of folic acid and vitamin B12 against nicotine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in pancreatic islets of the rat. Pharm. Biol. 2016, 54, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.G.; Li, W.H.; Lin, Z.Q.; Wang, L.X. Effects of folic acid on cardiac myocyte apoptosis in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2008, 22, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaar, M.C.; Stroes, E.; Rabelink, T.J. Folates and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniades, C.; Shirodaria, C.; Warrick, N.; Cai, S.; de Bono, J.; Lee, J.; Leeson, P.; Neubauer, S.; Ratnatunga, C.; Pillai, R.; et al. 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate Rapidly Improves Endothelial Function and Decreases Superoxide Production in Human Vessels Effects on Vascular Tetrahydrobiopterin Availability and Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Coupling. Circulation 2006, 114, 1193–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, S.N.; McDowell, I.F.; Moat, S.J.; Payne, N.; Durrant, H.J.; Lewis, M.J.; Goodfellow, J. Folic Acid Improves Endothelial Function in Coronary Artery Disease via Mechanisms Largely Independent of Homocysteine Lowering. Circulation 2002, 105, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Title, L.M.; Cummings, P.M.; Giddens, K.; Genest, J.J., Jr.; Nassar, B.A. Effect of folic acid and antioxidant vitamins on endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.C.; Ueland, P.M.; Obeid, O.A.; Wrigley, J.; Refsum, H.; Kooner, J.S. Improved vascular endothelial function after oral B vitamins: An effect mediated through reduced concentrations of free plasma homocysteine. Circulation 2000, 102, 2479–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doshi, S.N.; McDowell, I.F.; Moat, S.J.; Lang, D.; Newcombe, R.G.; Kredan, M.B.; Lewis, M.J.; Goodfellow, J. Folate improves endothelial function in coronary artery disease: An effect mediated by reduction of intracellular superoxide? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2001, 21, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, F.; Luo, H.; Lin, H.; Meng, L.; Jiang, C.; Guo, Y.; Chi, J.; Guo, H. Folic acid delays development of atherosclerosis in lowdensity lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 3183–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Ahmadi, S.F.; Streja, E.; Molnar, M.Z.; Flegal, K.M.; Gillen, D.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Obesity paradox in end-stage kidney disease patients. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 56, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi, Y.; Qader, H.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Latest consensus and update on proteinenergy wasting in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2015, 18, 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salles, N.; Herrmann, F.; Sakbani, K.; Rapin, C.H.; Sieber, C. High vitamin B12 level: A strong predictor of mortality in elderly inpatients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 917–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seetharam, B.; Li, N. Transcobalamin II and its cell surface receptor. Vitam. Horm. 2000, 59, 337–366. [Google Scholar]

- Sviri, S.; Khalaila, R.; Daher, S.; Bayya, A.; Linton, D.M.; Stav, I.; van Heerden, P.V. Increased Vitamin B12 levels are associated with mortality in critically ill medical patients. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamgbola, O.F. Pattern of resistance to erythropoietin-stimulating agents in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 464–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifan, C.; Samarneh, M.; Shtaynberg, N.; Nasr, R.; El-Charabaty, E.; El-Sayegh, S. Treatment of confirmed B12 deficiency in hemodialysis patients improves Epogen requirements. Int. J. Nephrol. Renovasc. Dis. 2013, 6, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brustolin, S.; Giugliani, R.; Félix, T.M. Genetics of homocysteinemetabolism and associated disorders. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homberger, A.; Linnebank, M.; Winter, C.; Willenbring, H.; Marquardt, T.; Harms, E.; Koch, H.G. Genomic structure and transcript variants of the human methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 8, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristalli, C.P.; Zannini, C.; Comai, G.; Baraldi, O.; Cuna, V.; Cappuccilli, M.; Mantovani, V.; Natali, N.; Cianciolo, G.; La Manna, G. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, MTHFR, polymorphisms and predisposition to different multifactorial disorders. Genes Genomics 2017, 39, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rady, P.L.; Szucs, S.; Grady, J.; Hudnall, S.D.; Kellner, L.H.; Nitowsky, H.; Tyring, S.K.; Matalon, R.K. Genetic polymorphisms of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and methionine synthase reductase (MTRR) in ethnic populations in Texas; a report of a novel MTHFR polymorphic site, G1793A. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2002, 107, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrone, E.M.; Hornberger, J.M.; Zehnder, J.L.; McCann, L.M.; Coplon, N.S.; Fortmann, S.P. Randomized trial of folic acid for prevention of cardiovascular events in end-stage renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trovato, F.M.; Catalano, D.; Ragusa, A.; Martines, G.F.; Pirri, C.; Buccheri, M.A.; Di Nora, C.; Trovato, G.M. Relationship of MTHFR gene polymorphisms with renal and cardiac disease Send to World. J. Nephrol. 2015, 4, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Bostom, A.G.; Shemin, D.; Lapane, K.L.; Hume, A.L.; Yoburn, D.; Nadeau, M.R.; Bendich, A.; Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. High-dose-B vitamin treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia in dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1996, 49, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, O.; Elmtaoua, S.; Zellama, D.; Omezzine, A.; Moussa, A.; Rejeb, J.; Boumaiza, I.; Bouacida, L.; Rejeb, N.B.; Achour, A.; et al. The C677T MTHFR genotypes influence the efficacy of B9 and B12 vitamins supplementation to lowering plasma total homocysteine in hemodialysis. J. Nephrol. 2016, 29, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Li, J.; Qin, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gottesman, R.F.; Tang, G.; Wang, B.; Chen, D.; He, M.; et al. Efficacy of Folic Acid Therapy in Primary Prevention of Stroke among Adults with Hypertension in China: The CSPPT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015, 313, 1325–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostom, A.G.; Shemin, D.; Bagley, P.; Massy, Z.A.; Zanabli, A.; Christopher, K.; Spiegel, P.; Jacques, P.F.; Dworkin, L.; Selhub, J. Controlled comparison of L-5- methyltetrahydrofolate versus folic acid for the treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia in hemodialysis patients. Circulation 2000, 101, 2829–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierkes, J.; Domröse, U.; Ambrosch, A.; Schneede, J.; Guttormsen, A.B.; Neumann, K.H.; Luley, C. Supplementation with vitamin B12 decreases homocystein and methylmalonic acid but also serum folate in patients with end stage renal disease. Metabolism 1999, 48, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A.; De Angelis, S.; Casciani, S.; Ruggia, R.; Di Giovamberardino, G.; Noce, A.; Splendiani, G.; Cortese, C.; Federici, G.; Dessì, M. Effects of folic acid before and after vitamin B12 on plasma homocysteine concentrations in hemodialysis patients with known MTHFR genotypes. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, R.; Bonnardeaux, A.; Geadah, D.; Busque, L.; Lebrun, M.; Ouimet, D.; Leblanc, M. Hyperhomocysteinemia in hemodialysis patients: Effects of 12-month supplementation with hydrosoluble vitamins. Kidney Int. 2000, 58, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, R.; Kuhlmann, M.K.; Köhler, H.; Herrmann, W. Response of homocysteine, cystathionine, and methylmalonic acid to vitamin treatment in dialysis patients. Clin. Chem. 2005, 51, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malinow, M.R.; Nieto, F.J.; Kruger, W.D.; Duell, P.B.; Hess, D.L.; Gluckman, R.A.; Block, P.C.; Holzgang, C.R.; Anderson, P.H.; Seltzer, D.; et al. The effects of folic acid supplementation on plasma total homocysteine are modulated by multivitamin use and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase genotypes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 1157–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Qin, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, J.; Liang, M.; Wang, B.; Huo, Y.; Hou, F.F.; Investigators of the Renal Substudy of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial (CSPPT). Efficacy of folic acid therapy on the progression of chronic kidney disease: The Renal Substudy of the China Stroke Primary Prevention Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, S.E.; Curry, C.J.; Toriello, H.V. ACMG Practice Guideline: Lack of evidence for MTHFR polymorphism testing. Genet Med. 2013, 15, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, D.S.; Law, M.; Morris, J.K. Homocysteine and cardiovascular disease: Evidence on causality from a metaanalysis. BMJ 2002, 325, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homocysteine Studies Collaboration. Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2002, 288, 2015–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Block, G.; Humphreys, M.H.; Kopple, J.D. Reverse epidemiology of cardiovascular risk factors in maintenance dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducloux, D.; Klein, A.; Kazory, A.; Devillard, N.; Chalopin, J.M. Impact of malnutrition-inflammation on the association between homocysteine and mortality. Kidney Int. 2006, 69, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, M.; Stenvinkel, P.; Qureshi, A.R.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Bárány, P.; Heimbürger, O.; Vonesh, E.F.; Lindholm, B. The reverse epidemiology of plasma total homocysteine as a mortality risk factor is related to the impact of wasting and inflammation. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2007, 22, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Ma, X.; Peng, H.; Lou, T. High Prevalence of Hyperhomocysteinemia and Its Association with Target Organ Damage in Chinese Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anan, F.; Takahashi, N.; Shimomura, T.; Imagawa, M.; Yufu, K.; Nawata, T.; Nakagawa, M.; Yonemochi, H.; Eshima, N.; Saikawa, T.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia is a significant risk factor for silent cerebral infarction in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis. Metabolism 2006, 55, 656–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.P.; Nemirovsky, D.; Kim, M.; Geer, E.B.; Farkouh, M.E.; Winston, J.; Halperin, J.L.; Robbins, M.J. Elevated homocysteine levels in patients with end-stage renal disease. Mt. Sinai. J. Med. 2005, 72, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- London, G.M.; Pannier, B.; Agharazii, M.; Guerin, A.P.; Verbeke, F.H.; Marchais, S.J. Forearm reactive hyperemia and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Block, G.; Humphreys, M.H.; McAllister, C.J.; Kopple, J.D. A low rather than a high, total plasma homocysteine is an indicator of poor outcome in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2004, 15, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccianti, G.; Baragetti, I.; Bamonti, F.; Furiani, S.; Dorighet, V.; Patrosso, C. Plasma homocysteine levels and cardiovascular mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease. J. Nephrol. 2004, 17, 405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bayés, B.; Pastor, M.C.; Bonal, J.; Juncà, J.; Hernandez, J.M.; Riutort, N.; Foraster, A.; Romero, R. Homocysteine, C-reactive protein, lipid peroxidation and mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2003, 18, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallamaci, F.; Zoccali, C.; Tripepi, G.; Fermo, I.; Benedetto, F.A.; Cataliotti, A.; Bellanuova, I.; Malatino, L.S.; Soldarini, A.; CREED Investigators. Hyperhomocysteinemia predicts cardiovascular outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducloux, D.; Bresson-Vautrin, C.; Kribs, M.; Abdelfatah, A.; Chalopin, J.M. C-reactive protein and cardiovascular disease in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002, 62, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraki, T.; Takegoshi, T.; Kitoh, C.; Kajinami, K.; Wakasugi, T.; Hirai, J.; Shimada, T.; Kawashiri, M.; Inazu, A.; Koizumi, J.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia, diabetes mellitus, and carotid atherosclerosis independently increase atherosclerotic vascular disease outcome in Japanese patients with end-stage renal disease. Clin. Nephrol. 2001, 56, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wrone, E.M.; Zehnder, J.L.; Hornberger, J.M.; McCann, L.M.; Coplon, N.S.; Fortmann, S.P. An MTHFR variant, homocysteine, and cardiovascular comorbidity in renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001, 60, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierkes, J.; Domröse, U.; Westphal, S.; Ambrosch, A.; Bosselmann, H.P.; Neumann, K.H.; Luley, C. Cardiac troponin T predicts mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease. Circulation 2000, 102, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suliman, M.E.; Qureshi, A.R.; Bárány, P.; Stenvinkel, P.; Filho, J.C.; Anderstam, B.; Heimbürger, O.; Lindholm, B.; Bergström, J. Hyperhomocysteinemia, nutritional status, and cardiovascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2000, 57, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunz, K.; Petitjean, P.; Lisri, M.; Chantrel, F.; Koehl, C.; Wiesel, M.L.; Cazenave, J.P.; Moulin, B.; Hannedouche, T.P. Cardiovascular morbidity and endothelial dysfunction in chronic haemodialysis patients: Is homocyst(e)ine the missing link? Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1999, 14, 1934–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manns, B.J.; Burgess, E.D.; Hyndman, M.E.; Parsons, H.G.; Schaefer, J.P.; Scott-Douglas, N.W. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia and the prevalence of atherosclerotic vascular disease in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1999, 34, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirrs, S.; Duncan, L.; Djurdjev, O.; Nussbaumer, G.; Ganz, G.; Frohlich, J.; Levin, A. Homocyst(e)ine and vascular access complications in haemodialysis patients: Insights into a complex metabolic relationship. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 1999, 14, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustapha, A.; Naso, A.; Nahlawi, M.; Gupta, A.; Arheart, K.L.; Jacobsen, D.W.; Robinson, K.; Dennis, V.W. Prospective study of hyperhomocysteinemia as an adverse cardiovascular risk factor in end-stage renal disease. Circulation 1998, 97, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vychytil, A.; Födinger, M.; Wölfl, G.; Enzenberger, B.; Auinger, M.; Prischl, F.; Buxbaum, M.; Wiesholzer, M.; Mannhalter, C.; Hörl, W.H.; et al. Major determinants of hyperhomocysteinemia in peritoneal dialysis patients. Kidney Int. 1998, 53, 1775–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostom, A.G.; Shemin, D.; Verhoef, P.; Nadeau, M.R.; Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J.; Dworkin, L.; Rosenberg, I.H. Elevated fasting total plasma homocysteine levels and cardiovascular disease outcomes in maintenance dialysis patients. A. prospective study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 2554–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, K.; Gupta, A.; Dennis, V.; Arheart, K.; Chaudhary, D.; Green, R.; Vigo, P.; Mayer, E.L.; Selhub, J.; Kutner, M.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia confers an independent increased risk of atherosclerosis in end-stage renal disease and is closely linked to plasma folate and pyridoxine concentrations. Circulation 1996, 94, 2743–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachmann, J.; Tepel, M.; Raidt, H.; Riezler, R.; Graefe, U.; Langer, K.; Zidek, W. Hyperhomocysteinemia and the risk for vascular disease in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1995, 6, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bostom, A.G.; Shemin, D.; Lapane, K.L.; Miller, J.W.; Sutherland, P.; Nadeau, M.; Seyoum, E.; Hartman, W.; Prior, R.; Wilson, P.W.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia and traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in end-stage renal disease patients on dialysis: A case-control study. Atherosclerosis 1995, 114, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Lin, Y.F.; Lo, L.; Liao, M.T.; Lu, K.C. Role of homocysteine in end-stage renal disease. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 45, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righetti, M.; Ferrario, G.M.; Milani, S.; Serbelloni, P.; La Rosa, L.; Uccellini, M.; Sessa, A. Effects of folic acid treatment on homocysteine levels and vascular disease in hemodialysis patients. Med. Sci. Monit. 2003, 9, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zoungas, S.; McGrath, B.P.; Branley, P.; Kerr, P.G.; Muske, C.; Wolfe, R.; Atkins, R.C.; Nicholls, K.; Fraenkel, M.; Hutchison, B.G.; et al. Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in the Atherosclerosis and Folic Acid Supplementation Trial (ASFAST) in Chronic Renal Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, R.L.; Hartigan, P.; Kaufman, J.S.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Warren, S.R.; Guarino, P.D.; Gaziano, J.M.; Veterans Affairs Site Investigators. Effect of Homocysteine Lowering on Mortality and Vascular Disease in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease and End-stage Renal Disease. JAMA 2007, 298, 1163–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, J.; Kropf, S.; Domröse, U.; Westphal, S.; Borucki, K.; Luley, C.; Neumann, K.H.; Dierkes, J. B Vitamins and the Risk of Total Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease in End-Stage Renal Disease Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Circulation 2010, 121, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Huo, Y.; Langman, C.B.; Hou, F.; Chen, Y.; Matossian, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, X. Folic acid therapy and cardiovascular disease in ESRD or advanced chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Tan, S.; Xu, Y.; Chandra, A.; Shi, C.; Song, B.; Qin, J.; Gao, Y. Vitamin B supplementation, homocysteine levels, and the risk of cerebrovascular disease: A meta-analysis. Neurology 2013, 81, 1298–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Guo, L.L.; Cai, L.L.; Zhu, X.J.; Shu, J.L.; Liu, X.L.; Jin, H.M. Homocysteine-lowering therapy does not lead to reduction in cardiovascular outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients: A meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigwekar, S.U.; Kang, A.; Zoungas, S.; Cass, A.; Gallagher, M.P.; Kulshrestha, S.; Navaneethan, S.D.; Perkovic, V.; Strippoli, G.F.M.; Jardine, M.J. Interventions for lowering plasma homocysteine levels in dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, A.A.; Eliasziw, M.; Cattran, D.C.; Churchill, D.N.; Oliver, M.J.; Fine, A.; Dresser, G.K.; Spence, J.D. Effect of B-vitamin therapy on progression of diabetic nephropathy: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010, 303, 1603–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, J.F.; Sheridan, P.; McQueen, M.J.; Held, C.; Arnold, J.M.; Fodor, G.; Yusuf, S.; Lonn, E.M. HOPE-2 investigators. Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in people with chronic kidney disease—results of the renal Hope-2 study. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2008, 23, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vianna, A.C.; Mocelin, A.J.; Matsuo, T.; Morais-Filho, D.; Largura, A.; Delfino, V.A.; Soares, A.E.; Matni, A.M. Uremic hyperhomocysteinemia: A randomized trial of folate treatment for the prevention of cardiovascular events. Hemodial. Int. 2007, 11, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righetti, M.; Serbelloni, P.; Milani, S.; Ferrario, G. Homocysteine-lowering vitamin B treatment decreases cardiovascular events in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2006, 24, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Yuan, Y.; Guo, J.; Yang, S.; Xu, X.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Qin, X.; Tang, G.; Huo, Y.; et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia predicts renal function decline: A prospective study in hypertensive adults. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, G.; Cappuccilli, M.L.; Cianciolo, G.; Conte, D.; Comai, G.; Carretta, E.; Scolari, M.P.; Stefoni, S. Cardiovascular disease in kidney transplant recipients. The prognostic value of inflammatory cytokine genotypes. Transplantation 2010, 89, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.N.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Selhub, J.; Levey, A.S.; Bostom, A.G. Hyperhomocysteinemia in renal transplant recipients. Am. J. Transpl. 2002, 2, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostom, A.G.; Gohh, R.Y.; Liaugaudas, G.; Beaulieu, A.J.; Han, H.; Jacques, P.F.; Dworkin, L.; Rosenberg, I.H.; Selhub, J. Prevalence of mild fasting hyperhomocysteinemia in renal transplant versus coronary artery disease patients after fortification of cereal grain flour with folic acid. Atherosclerosis 1999, 145, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostom, A.G.; Gohh, R.Y.; Beaulieu, A.J.; Nadeau, M.R.; Hume, A.L.; Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J.; Rosenberg, I.H. Treatment of hyperhomocysteinemia in renal transplant recipients. A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 1997, 127, 1089–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, A.J.; Gohh, R.Y.; Han, H.; Hakas, D.; Jacques, P.F.; Selhub, J.; Bostom, A.G. Enhanced reduction of fasting total homocysteine levels with supraphysiological versus standard multivitamin dose folic acid supplementation in renal transplant recipients. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1999, 19, 2918–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostom, A.G.; Carpenter, M.A.; Kusek, J.W.; Levey, A.S.; Hunsicker, L.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Selhub, J.; Jacques, P.F.; Cole, E.; Gravens-Mueller, L.; et al. Homocysteine-lowering and cardiovascular disease outcomes in kidney transplant recipients: Primary results from the Folic Acid for Vascular Outcome Reduction in Transplantation trial. Circulation 2011, 123, 1763–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]