A Review of the In Vivo Evidence Investigating the Role of Nitrite Exposure from Processed Meat Consumption in the Development of Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

:1. Introduction

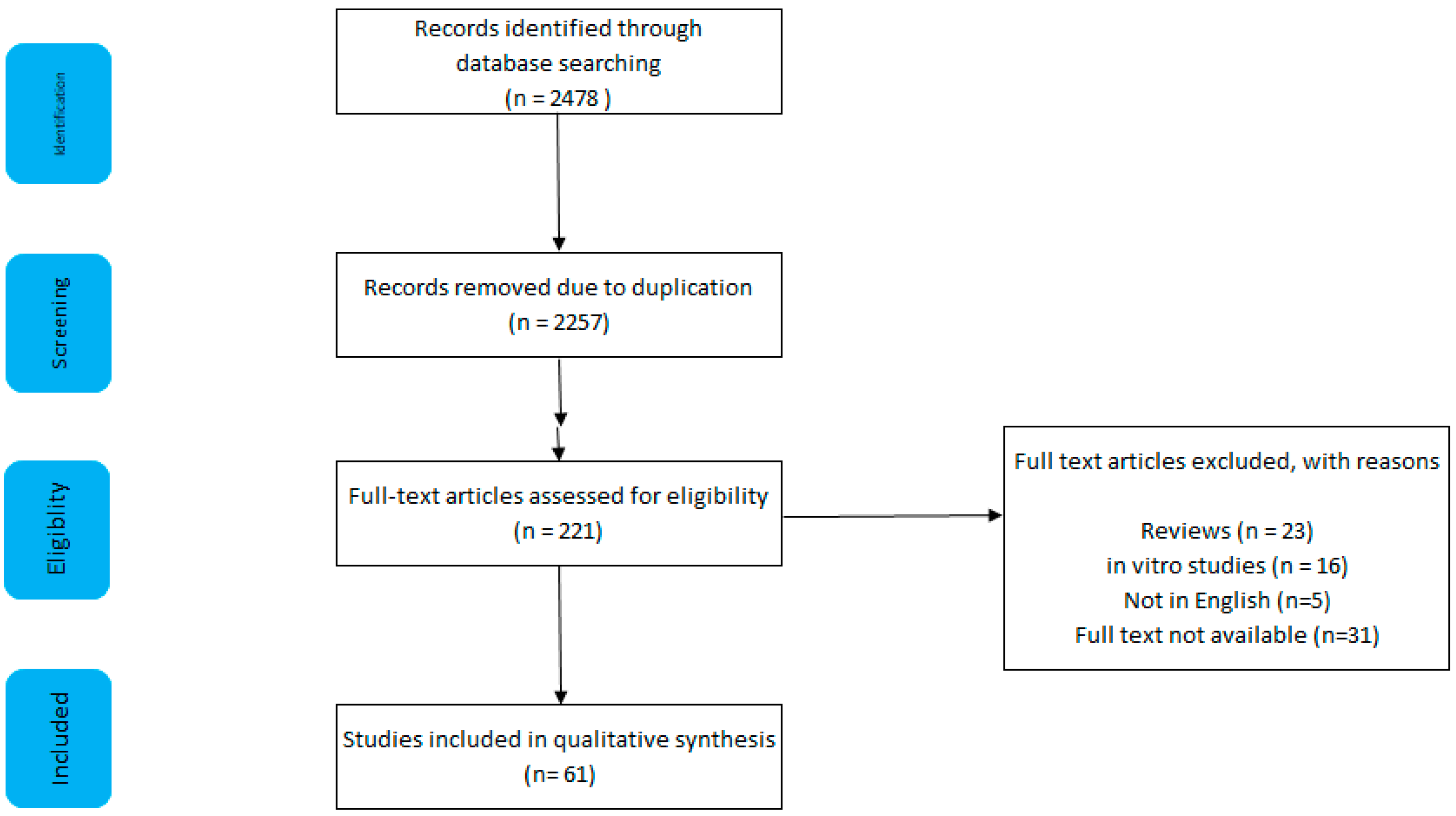

1.1. Methods

1.2. Inclusion and Exclusion

1.3. Results

2. Preclinical Evidence

3. Clinical Evidence

Studies Focusing on Nitrite-Containing Meat and CRC

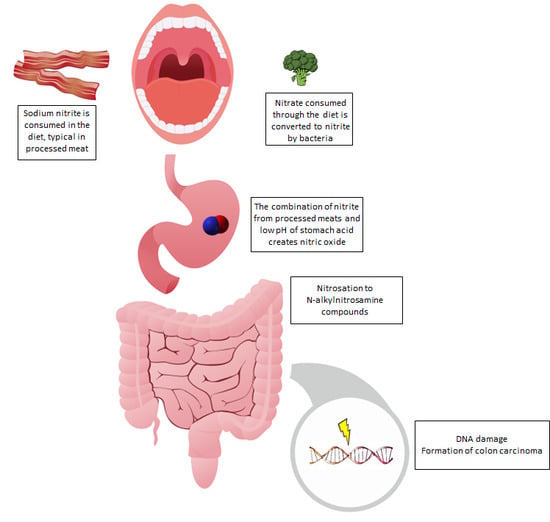

4. Potential Mechanisms

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IARC Working group. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; The Lancet Oncology: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; Choice: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries: Middletown, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Cancer Research Fund. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective; American Institute for Cancer Research: Arlington, VA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bouvard, V.; Loomis, D.; Guyton, K.Z.; Grosse, Y.; El Ghissassi, F.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Guha, N.; Mattock, H.; Straif, K. Carcinogenicity of consumption of red and processed meat. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1599–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 2657–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huxley, R.R.; Clifton, P.; Czernichow, S.; Parr, C.L.; Woodward, M.; Ansary-Moghaddam, A.; Ansary-Moghaddam, A. The impact of dietary and lifestyle risk factors on risk of colorectal cancer: A quantitative overview of the epidemiological evidence. Int. J. Cancer 2009, 125, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.D.; Miller, A.J.; Cushing, C.A.; Lowe, K.A. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: A quantitative review of prospective epidemiologic studies. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2010, 19, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, D.S.M.; Lau, R.; Aune, D.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Red and Processed Meat and Colorectal Cancer Incidence: Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, C.M.; Chang-Claude, J.; Slattery, M.L.; Pflugeisen, B.M.; Lin, Y.; Duggan, D.; Nan, H.; Lemire, M.; Rangrej, J.; Figueiredo, J.C.; et al. Characterization of gene-environment interactions for colorectal cancer susceptibility loci. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 2036–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, N.M.; Sasazuki, S.; Tsugane, S.; Inoue, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Otani, T.; Sawada, N.; Shimazu, T.; Yamaji, T.; Tsuji, I.; et al. Meat Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An Evaluation Based on a Systematic Review of Epidemiologic Evidence Among the Japanese Population. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 44, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, C.; Tao, G.; Zhao, L.; Tang, S.; Shu, Z.; Cai, J.; Dai, S.; et al. Red and Processed Meat Intake Is Associated with Higher Gastric Cancer Risk: A Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Observational Studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.M.; Wei, C.; Ensor, J.E.; Smolenski, D.J.; Amos, C.I.; Levin, B.; Berry, D.A. Meta-analyses of colorectal cancer risk factors. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, D.; Khlat, M. Studies of cancer in migrants: Rationale and methodology. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.L.; Pierre, F.; Corpet, D.E. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: A review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mey, E.; de Maere, H.; Paelinck, H.; Fraeye, I. Volatile N-nitrosamines in meat products: Potential precursors, influence of processing, and mitigation strategies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2909–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenni, F.Z.; Taché, S.; Naud, N.; Guéraud, F.; Hobbs, D.A.; Kunhle, G.G.C.; Pierre, F.H.; Corpet, D.E. Heme-induced biomarkers associated with red meat promotion of colon cancer are not modulated by the intake of nitrite. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnaud, G.; Peiffer, G.; Taché, S.; Corpet, D.E. Effect of meat (beef, chicken, and bacon) on rat colon carcinogenesis. Nutr. Cancer 1998, 32, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bastide, N.M.; Chenni, F.; Audebert, M.; Santarelli, R.L.; Naud, N.; Baradat, M.; Jouanin, I.; Surya, R.; Hobbs, D.A.; Kuhnle, G.; et al. A Central Role for Heme Iron in Colon Carcinogenesis Associated with Red Meat Intake. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Zahid, M.; Anwar, M.M.; Pennington, K.L.; Cohen, S.M.; Wisecarver, J.L.; Shostrom, V.; Mirvish, S.S. Suggestive evidence for the induction of colonic aberrant crypts in mice fed sodium nitrite. Nutr. Cancer 2015, 68, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.L.; Vendeuvre, J.-L.; Naud, N.; Taché, S.; Guéraud, F.; Viau, M.; Genot, C.; Corpet, D.E.; Pierre, F.H. Meat processing and colon carcinogenesis: Cooked, nitrite-treated, and oxidized high-heme cured meat promotes mucin-depleted foci in rats. Cancer Prev. Res. 2010, 3, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, R.L.; Naud, N.; Taché, S.; Guéraud, F.; Vendeuvre, J.-L.; Zhou, L.; Anwar, M.M.; Mirvish, S.S.; Corpet, D.E.; Pierre, F.H. Calcium inhibits promotion by hot dog of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced mucin-depleted foci in rat colon. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 2533–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, F.H.; Martin, O.C.; Santarelli, R.L.; Taché, S.; Naud, N.; Guéraud, F.; Audebert, M.; Dupuy, J.; Meunier, N.; Attaix, D.; et al. Calcium and α-tocopherol suppress cured-meat promotion of chemically induced colon carcinogenesis in rats and reduce associated biomarkers in human volunteers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastide, N.M.; Naud, N.; Nassy, G.; Vendeuvre, J.-L.; Taché, S.; Guéraud, F.; Hobbs, D.A.; Kuhnle, G.G.; Corpet, D.E.; Pierre, F.H.F. Red Wine and Pomegranate Extracts Suppress Cured Meat Promotion of Colonic Mucin-Depleted Foci in Carcinogen-Induced Rats. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, F.H.F.; Santarelli, R.L.; Allam, O.; Taché, S.; Naud, N.; Guéraud, F.; Corpet, D.E.; Chartron, M. Freeze-dried ham promotes azoxymethane-induced mucin-depleted foci and aberrant crypt foci in rat colon. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvish, S.S.; Haorah, J.; Zhou, L.; Hartman, M.; Morris, C.R.; Clapper, M.L. N-nitroso compounds in the gastrointestinal tract of rats and in the feces of mice with induced colitis or fed hot dogs or beef. Carcinogenesis 2003, 24, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parnaud, G.; Pignatelli, B.; Peiffer, G.; Taché, S.; Corpet, D.E. Endogenous N-Nitroso Compounds, and Their Precursors, Present in Bacon, Do Not Initiate or Promote Aberrant Crypt Foci in the Colon of Rats. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 38, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cross, A.J.; Pollock, J.R.A.; Bingham, S.A. Haem, not protein or inorganic iron, is responsible for endogenous intestinal N-nitrosation arising from red meat. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 2358–2360. [Google Scholar]

- Corpet, D.E.; Taché, S. Most effective colon cancer chemopreventive agents in rats: A systematic review of aberrant crypt foci and tumor data, ranked by potency. Nutr. Cancer 2002, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Femia, A.P.; Dolara, P.; Caderni, G. Mucin-depleted foci (MDF) in the colon of rats treated with azoxymethane (AOM) are useful biomarkers for colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2004, 25, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yin, T.; Feng, Y.; Cona, M.M.; Huang, G.; Liu, J.; Song, S.; Jiang, Y.; Xia, Q.; Swinnen, J.V.; et al. Mammalian models of chemically induced primary malignancies exploitable for imaging-based preclinical theragnostic research. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2015, 5, 708–729. [Google Scholar]

- Calmels, S.; Béréziat, J.C.; Ohshima, H.; Bartsch, H. Bacterial formation of N-nitroso compounds from administered precursors in the rat stomach after omeprazole-induced achlorhydria. Carcinogenesis 1991, 12, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, S.; Shimizu, N.; Nagata, C.; Shimizu, H.; Kametani, M.; Takeyama, N.; Ohnuma, T.; Matsushita, S. The relationship between the consumption of meat, fat, and coffee and the risk of colon cancer: A prospective study in Japan. Cancer Lett. 2006, 244, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbohm, R.A.; Brandt, P.A.V.D.; van’t Veer, P.; Brants, H.A.; Dorant, E.; Sturmans, F.; Hermus, R.J. A prospective cohort study on the relation between meat consumption and the risk of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 718–723. [Google Scholar]

- Tajima, K.; Tominaga, S. [A comparative case-control study of stomach and large intestinal cancers]. Gan No Rinsho. Jpn. J. Cancer Clin. 1986, 32, 705–716. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, F.; Pasche, C.; Lucchini, F.; Bosetti, C.; La Vecchia, C. Processed meat and the risk of selected digestive tract and laryngeal neoplasms in Switzerland. Ann. Oncol. 2004, 15, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haenszel, W.; Segi, M.; Kurihara, M.; Locke, F.B.; Berg, J.W. Large-Bowel Cancer in Hawaiian Japanese2. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1973, 51, 1765–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.B.; Wolf, D.A. Case-control study of proximal and distal colon cancer and diet in Wisconsin. Int. J. Cancer 1988, 42, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidoli, E.; Franceschi, S.; Talamini, R.; Barra, S.; La Vecchia, C. Food consumption and cancer of the colon and rectum in north-eastern Italy. Int. J. Cancer 1992, 50, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, A.; Díaz, M.P.; Muñoz, S.E.; Lantieri, M.J.; Eynard, A.R. Characterization of meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in Cordoba, Argentina. Nutrition 2003, 19, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosato, V.; Bosetti, C.; Levi, F.; Polesel, J.; Zucchetto, A.; Negri, E.; La Vecchia, C. Risk factors for young-onset colorectal cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; La Vecchia, C.; Desmeules, M.; Negri, E.; Mery, L.; Epidemio, C.C.R. Meat and Fish Consumption and Cancer in Canada. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Verdier, M.G.; Hagman, U.; Peters, R.K.; Steineck, G.; Övervik, E. Meat, cooking methods and colorectal cancer: A case-referent study in Stockholm. Int. J. Cancer 1991, 49, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macquart-Moulin, G.; Riboli, E.; Cornée, J.; Charnay, B.; Berthezene, P.; Day, N. Case-control study on colorectal cancer and diet in marseilles. Int. J. Cancer 1986, 38, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, C.L.; Hjartåker, A.; Lund, E.; Veierød, M.B. Meat intake, cooking methods and risk of proximal colon, distal colon and rectal cancer: The Norwegian Women and Cancer (NOWAC) cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 1153–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, S.; Coles, B.; Sinha, R.; MacLeod, S.; Ratnasinghe, D.L.; Stotts, C.; Kadlubar, F.F.; Ambrosone, C.B.; Lang, N.P. Analysis of total meat intake and exposure to individual heterocyclic amines in a case-control study of colorectal cancer: Contribution of metabolic variation to risk. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2002, 506, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Murphy, N.; Key, T.J. Diet and colorectal cancer in UK Biobank: A prospective study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, A.J.; Ferrucci, L.M.; Risch, A.; Graubard, B.I.; Ward, M.H.; Park, Y.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Schatzkin, A.; Sinha, R. A Large Prospective Study of Meat Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk: An Investigation of Potential Mechanisms Underlying this Association. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 2406–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.; Giovannucci, E.; Byrne, C.; Platz, E.A.; Fuchs, C.; Willett, W.C.; Sinha, R. Meat Mutagens and Risk of Distal Colon Adenoma in a Cohort of U.S. Men. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 1120–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, D.R.; MacInnis, R.J.; Hodge, A.M.; Hopper, J.L.; Haydon, A.M.; Giles, G.G. Red meat, chicken, and fish consumption and risk of colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Norat, T.; Bingham, S.; Riboli, E. RESPONSE: Re: Meat, Fish, and Colorectal Cancer Risk: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2005, 97, 1788–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.C.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Rosner, B.A.; Speizer, F.E. Relation of Meat, Fat, and Fiber Intake to the Risk of Colon Cancer in a Prospective Study among Women. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.J.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Gail, M.H.; Hollenbeck, A.R.; Schatzkin, A.; Sinha, R. A prospective study of red and processed meat intake in relation to cancer risk. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohsoonthorn, P.; Danvivat, D. Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors: A Case-control Study in Bangkok. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 1995, 8, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stefani, E.; Boffetta, P.; Ronco, A.L.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Correa, P.; Acosta, G.; Mendilaharsu, M.; Luaces, M.E.; Silva, C. Processed meat consumption and risk of cancer: A multisite case–control study in Uruguay. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1584–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostick, R.M.; Potter, J.D.; Kushi, L.H.; Sellers, T.A.; Steinmetz, K.A.; McKenzie, D.R.; Gapstur, S.M.; Folsom, A.R. Sugar, meat, and fat intake, and non-dietary risk factors for colon cancer incidence in Iowa women (United States). Cancer Causes Control 1994, 5, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takachi, R.; Tsubono, Y.; Baba, K.; Inoue, M.; Sasazuki, S.; Iwasaki, M.; Tsugane, S.; Japan Public Health Center-based Prospective Study Group. Red meat intake may increase the risk of colon cancer in Japanese, a population with relatively low red meat consumption. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 20, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Nakaya, N.; Kuriyama, S.; Nishino, Y.; Tsubono, Y.; Tsuji, I. Meat consumption and risk of colorectal cancer in Japan: The Miyagi Cohort Study. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2006, 15, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, S.M.; Cook, N.R.; Lee, I.-M.; Buring, J.E. Dietary Fat and Fatty Acids and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 160, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knekt, P.; Dich, J.; Hakulinen, T.; Järvinen, R. Risk of colorectal and other gastro-intestinal cancers after exposure to nitrate, nitrite and N-nitroso compounds: A follow-up study. Int. J. Cancer 1999, 80, 852–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.D.; Satia, J.A.; Adair, L.S.; Stevens, J.; Galanko, J.; Keku, T.O.; Sandler, R.S. Associations of red meat, fat, and protein intake with distal colorectal cancer risk. Nutr. Cancer 2010, 62, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, E.; Obrador, A.; Stiggelbout, A.; Bosch, F.X.; Mulet, M.; Munoz, N.; Kaldor, J. A population-based case-control study of colorectal cancer in Majorca. I. Dietary factors. Int. J. Cancer 1990, 45, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dales, L.G.; Friendman, G.D.; Ury, H.K.; Grossman, S.; Williams, S.R. A case control study of relationships of diet and other traits to colorectal cancer in American blacks. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1978, 109, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.D.; Kim, A.; Lewinger, J.P.; Ulrich, C.M.; Potter, J.D.; Cotterchio, M.; Le Marchand, L.; Stern, M.C. Meat intake, cooking methods, dietary carcinogens, and colorectal cancer risk: Findings from the Colorectal Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Med. 2015, 4, 936–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balder, H.F.; Vogel, J.; Jansen, M.C.; Weijenberg, M.P.; Westenbrink, S.; Van Der Meer, R.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Brandt, P.A.V.D. Heme and Chlorophyll Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the Netherlands Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murtaugh, M.A.; Ma, K.-N.; Sweeney, C.; Caan, B.J.; Slattery, M.L. Meat consumption patterns and preparation, genetic variants of metabolic enzymes, and their association with rectal cancer in men and women. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Kono, S.; Toyomura, K.; Nagano, J.; Mizoue, T.; Moore, M.A.; Mibu, R.; Tanaka, M.; Kakeji, Y.; Maehara, Y.; et al. Meat, fish and fat intake in relation to subsite-specific risk of colorectal cancer: The Fukuoka Colorectal Cancer Study. Cancer Sci. 2007, 98, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietinen, P.; Malila, N.; Virtanen, M.; Hartman, T.J.; Tangrea, J.A.; Albanes, D.; Virtamo, J. Diet and risk of colorectal cancer in a cohort of Finnish men. Cancer Causes Control 1999, 10, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nöthlings, U.; Yamamoto, J.F.; Wilkens, L.R.; Murphy, S.P.; Park, S.-Y.; Henderson, B.E.; Kolonel, L.N.; Le Marchand, L. Meat and heterocyclic amine intake, smoking, NAT1 and NAT2 polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2009, 18, 2098–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinmetz, K.A.; Potter, J.D. Food-group consumption and colon cancer in the adelaide case-control study. II. Meat, poultry, seafood, dairy foods and eggs. Int. J. Cancer 1993, 53, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, S.; Favero, A.; La Vecchia, C.; Negri, E.; Conti, E.; Montella, M.; Giacosa, A.; Nanni, O.; DeCarli, A. Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer in Italy. Int. J. Cancer 1997, 72, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centonze, S.; Boeing, H.; Leoci, C.; Guerra, V.; Misciagna, G. Dietary habits and colorectal cancer in a low-risk area. Results from a population-based case-control study in southern Italy. Nutr. Cancer 1994, 21, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiemersma, E.W.; Kampman, E.; De Mesquita, H.B.B.; Bunschoten, A.; Van Schothorst, E.M.; Kok, F.J.; Kromhout, D. Meat consumption, cigarette smoking, and genetic susceptibility in the etiology of colorectal cancer: Results from a Dutch prospective study. Cancer Causes Control 2002, 13, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, E.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, G.A.; Ascherio, A.; Willett, W.C. Intake of fat, meat, and fiber in relation to risk of colon cancer in men. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 2390–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A. Meat Consumption and Risk of Colorectal Cancer. JAMA 2005, 293, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-A.; Shu, X.O.; Yang, G.; Li, H.; Gao, Y.-T.; Zheng, W. Animal origin foods and colorectal cancer risk: A report from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Nutr. Cancer 2009, 61, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Rafter, J.; Holmberg, L.; Bergkvist, L.; Wolk, A. Red meat consumption and risk of cancers of the proximal colon, distal colon and rectum: The Swedish Mammography Cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 113, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollberding, N.J.; Wilkens, L.R.; Henderson, B.E.; Kolonel, L.N.; Le Marchand, L. Meat consumption, heterocyclic amines and colorectal cancer risk: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, E1125–E1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egeberg, R.; Olsen, A.; Christensen, J.; Halkjær, J.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Overvad, K.; Tjønneland, A. Associations between Red Meat and Risks for Colon and Rectal Cancer Depend on the Type of Red Meat Consumed. J. Nutr. 2013, 143, 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flood, A.; Velie, E.M.; Sinha, R.; Chaterjee, N.; Lacey, J.V., Jr.; Schairer, C.; Schatzkin, A. Meat, Fat, and Their Subtypes as Risk Factors for Colorectal Cancer in a Prospective Cohort of Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 158, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iscovich, J.M.; L’Abbé, K.A.; Castelleto, R.; Calzona, A.; Bernedo, A.; Chopita, N.A.; Jmelnitzsky, A.C.; Kaldor, J. Colon cancer in Argentina. I: Risk from intake of dietary items. Int. J. Cancer 1992, 51, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, B.; Doll, R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int. J. Cancer 1975, 15, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricker, A. N-nitroso compounds and man: Sources of exposure, endogenous formation and occurrence in body fluids. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 1997, 6, 226–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veena, S.; Rashmi, S. A review on mechanism of nitrosamine formation, metabolism and toxicity in in vivo. Int. J. Toxicol. Pharmacol. Res. 2014, 6, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Evaluation of carcinogenic risks OveraIl Evaluations of Carcinogenicity; IARC Monographs: Lyon, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrer, J.; Kaina, B. Review O 6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in the defense against N-nitroso compounds and colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis 2013, 34, 2435–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beranek, D.T. Distribution of methyl and ethyl adducts following alkylation with monofunctional alkylating agents. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 1990, 231, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamataki, T.; Fujita, K.-I.; Nakayama, K.; Yamazaki, Y.; Miyamoto, M.; Ariyoshi, N. Role of human cytochrome p450 (CYP) in the metabolic activation of nitrosamine derivatives: Application of genetically engineered salmonella expressing human CYP. Drug Metab. Rev. 2002, 34, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhnle, G.G.; Story, G.W.; Reda, T.; Mani, A.R.; Moore, K.P.; Lunn, J.C.; Bingham, S.A. Diet-induced endogenous formation of nitroso compounds in the GI tract. Free. Radic. Boil. Med. 2007, 43, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Gapstur, S.M.; Shah, R.; Jacobs, E.J.; Campbell, P.T. Association between red and processed meat intake and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 2773–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelholm, M.; Kanerva, N.; Männistö, S. Association between red and processed meat consumption and chronic diseases: The confounding role of other dietary factors. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 69, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykhuizen, R.S.; Frazer, R.; Duncan, C.; Smith, C.C.; Golden, M.; Benjamin, N.; Leifert, C. Antimicrobial effect of acidified nitrite on gut pathogens: Importance of dietary nitrate in host defense. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 1422–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Schopfer, F.J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Ichikawa, T.; Baker, P.R.S.; Batthyany, C.; Chacko, B.K.; Feng, X.; Patel, R.P.; et al. Nitrated fatty acids: Endogenous anti-inflammatory signaling mediators. J. Boil. Chem. 2006, 281, 35686–35698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, B.; Kendzia, B.; Gustavsson, P.; Jöckel, K.H.; Johnen, G.; Pohlabeln, H.; Olsson, A.; Ahrens, W.; Gross, I.M.; Brüske, I.; et al. Cigarette smoking and lung cancer—Relative risk estimates for the major histological types from a pooled analysis of case–control studies. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 1210–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijinsky, W. N-Nitroso compounds in the diet. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 1999, 443, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospital, X.F.; Hierro, E.; Stringer, S.; Fernández, M. International Journal of Food Microbiology A study on the toxigenesis by Clostridium botulinum in nitrate and nitrite-reduced dry fermented sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 218, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Guardian. Revealed: No Need to Add Cancer Risk Nitrites to Ham. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/food/2019/mar/23/nitrites-ham-bacon-cancer-risk-additives-meat-industry-confidential--report (accessed on 17 October 2019).

| Author | Model | Intervention | Fat Content | Control | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [17] Parnaud et al. 1998 | Fischer rat | 30% bacon (freeze dried), 70% AIN-76 for 100 days 60% bacon for 30 days | 7%, 14%, 28% | AIN-76 formula with identical protein and fat (Casein and lard used to increase macros) | ↑ Fecal NOC level No ACF were detected in the colon of bacon-fed uninitiated rats. |

| [26] Parnaud et al. 2000 | Fischer rat | 30% bacon (freeze dried), 70% AIN-76 for 100 days 60% bacon for 100 days | 14% 28% | AIN 76 formula with identical protein and fat (casein, olive oil and lard used to increase macros) | ↓ACF by 12% in rats fed a diet with 30% bacon and by 20% in rats fed a diet with 60% bacon. |

| [25] Mirvish et al. 2003 | Sprague– Dawley rats and male mice of various strains | 18% hot dog, 82% TD-01407 SP 7 days 15% beef. 82% TD-01407 SP 7 days | 26 g/100 g | TD-01407 TD-98061 AIN-76A diet soy oil and casein added to increase macros | ↑ Fecal NOC in hot dog and beef fed compared with control. |

| [20] Santarelli et al. 2010 | Fischer rat | 55% processed pork (moist), 45% AIN76 | 15 g/100 g | AIN-76A | ↑ MDF in processed pork group. |

| [21] Pierre et al. 2010 | Fischer 344 rats | 55% cured ham (freeze dried), 45% AIN76A | - | Ain-76A | ↑ ACF and MDF in cured ham fed group. |

| [21] Santarelli et al. 2013 | Fischer rat | 55% processed meat (moist), 40% AIN76, 5% safflower oil | 30% | AIN-76A with 5% safflower | ↑ MDF in hot dog fed group. Addition of calcium carbonate suppresses lesions. |

| [16] Chenni et al. 2013 | F344 rats | AIN-76 with sodium nitrite in drinking water (1 g/L) nitrite (0.17 g/L) and nitrate (0.23 g/L) | - | AIN-76A | No change. |

| [22] Pierre et al. 2013 | Fischer 344 rats | 55 g (moist weight) experimental cured meat, 45 g AIN76 100 days | 15% | AIN-76A | ↑ MDF in cured meat fed group, compared with vitamin E and calcium supplemented groups. |

| [18] Bastide et al. 2015 | F344 ratsC57BL/6J ApcMin/+ miceApc+/+ mice | (0.17 g/L of NaNO2 and 0.23 g/L of NaNO3) added to water AIN-76A with 2.5% haemoglobin | - | AIN-76A | ↑ MDF in heme iron fed group. No change in nitrite fed group. |

| [19] Zhou et al. 2015 | A/J mice CF-1 mice | 0.5 or 1.0 g NaNO2/L 0, 1.0, 1.25, or 1.5 g NaNO2/L 18% hot dog | - | AIN93G | No change following hot dog ingestion. ↑ ACF in 1.5 g compared with untreated |

| [23] Bastide et al. 2017 | Fischer 344 rats | 50 g cooked, cured meat, 50 g AIN76 100 days vs polyphenol rich diet | - | Ain-76A | ↑ MDF in cured meat fed group. |

| Author | Sample Size | Colorectal Cancer Cases | Description of Processed Meat | Relative Risk (CI) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] Oba et al. 2005 | 31,552 | 213 | Processed meat | 1.98 (1.24–3.16)♂ 0.85 (0.50–1.43)♀ | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC in ♂ not ♀ |

| [33] Goldbohm et al. 1994 | 3123 | 393 | Processed meat | 1.72 (1.03–2.87) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [44] Parr et al. 2013 | 84,210 | 674 | Processed meat | 1.54 (1.08–2.19) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [48] Wu et al. 2006 | 14,032 | 581 ‡ | Processed meat | 1.52 (1.12–2.08) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [55] Bostick et al. 1994 | 35,215 | 212 | Processed meat | 1.51 (0.72–3.17) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [49] English et al. 2004 | 37,112 | 451 | Processed meat | 1.50 (1.1–2.0) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [50] Norat et al. 2005 | 478,040 | 1329 | Processed meat | 1.42 (1.09–1.86) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [56] Takachi et al. 2011 | 98,514 | 1145 | Processed meat | 1.27 (0.95–1.71)♂ 1.19 (0.82–1.74)♀ | No significant risk of CRC |

| [51] Willet et al. 1990 | 88,751 | 150 | Processed meat | 1.21 (0.53–2.72) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC in the 3rd quintile but not the 4th |

| [67] Pietinen et al. 1999 | 27, 111 | 185 | Processed meat | 1.20 (0.7–1.8) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [52] Cross et al. 2007 | 494,036 | 5107 | Processed meat | 1.20 (1.09–1.32) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [46] Bradbury et al. 2019 | 468,910 | 2576 | Processed meat | 1.19 (1.01–1.41) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [73] Giovannucci et al. 1994 | 47,949 | 205 | Processed meat | 1.16 (0.44–3.04) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [47] Cross et al. 2010 | 300,948 | 2719 | Processed meat | 1.16 (1.01–1.32) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [74] Chao et al. 2005 | 148,610 | 1197 | Processed meat | 1.13 (0.91–1.41) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [75] Lee et al. 2009 | 74,942 | 394 | Salted meat | 1.10 (0.8–1.4) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [76] Larsson et al. 2005 | 61,433 | 234ⱡ 155‡ | Processed meat | 1.07 (0.85–1.33) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [77] Ollberding et al. 2012 | 215,000 | 3404 | Processed meat | 1.06 (0.94–1.19) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [78] Egeberg et al. 2013 | 53,988 | 914 | Processed meat | 1.02 (0.78–1.34) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [79] Flood et al. 2002 | 45,496 | 487 | Processed meat | 0.97 (0.73–1.28) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [57] Sato et al. 2006 | 47,605 | 358 | Ham or sausage | 0.91 (0.61–1.35) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [58] Lin et al. 2004 | 37,547 | 202 | Processed meat | 0.85 (0.53–1.35) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [59] Knekt et al. 1999 | 9985 | 73 | Nitrite | 0.74 (0.34–1.63) | No significant risk of CRC |

| Author | Cases (n =) | Controls (n =) | Description of Processed Meat | Relative Risk (CI) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [53] Lohsoonthorn et al. 1995 | 279 | 279 | Bacon | 12.49 (1.68–269.1) | Significantly ↑ bacon consumption in cases group |

| [54] De Stefani et al. 2012 | 321 | 844 | Processed meat | 3.53 (1.93–6.46) 2.01 (1.07–3.76) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [34] Tajima and Tomina 1985 | 93 | 186 | Ham and sausage | 2.87 | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [35] Levi et al. 2004 | 323 | 1271 | Processed meat | 2.53 (1.50–4.27) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [36] Haenszel et al. 1973 | 179 | 357 | Sausage and other processed pork | 2.30Ϟ 1.77Ф 2.7҂ | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [37] Young and Wolf 1988 | 152 ⱡ 201 ‡ | 618 | Processed lunch meat | 1.85 (1.33–2.58) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [38] Bidoli et al. 1992 | 123¥ 125₸ | 699 | Salami and sausages | 1.8¥ 1.9₸ | Sig ↑ ¥ but not ₸ |

| [39] Navarro et al. 2003 | 287 | 566 | Cold cuts and sausages | 1.64 (1.16–2.32) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [40] Rosato et al. 2013 | 329 | 1361 | Processed meat | 1.56 (1.11–2.20) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [41] Hu et al. 2008 | 3174 | 5039 | Processed meats | 1.50 (1.2–1.8) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [60] Williams et al. 2010 | 945 | 959 | Processed meat | 1.36 (0.80–1.68)Ւ 1.02 (0.38–1.96)ⱦ | No significant risk of CRC |

| [61] Benito et al. 1990 | 286 | 498 | Processed meat | 1.36 | No significant risk of CRC |

| [42] De Verdier et al. 1991 | 559 | 505 | Sausage | 1.30 (0.8–1.9)¥ 1.7 (1.1–2.8)₸ | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [62] Dales et al. 1978 | 99 | 280 | Nitrite treated meats | 1.22 | No significant risk of CRC |

| [63] Joshi et al. 2015 | 3350 | 3504 | Processed meats | 1.20 (1.0–1.4) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [64] Balder et al. 2006 | 1535 | 4371 | Processed meats | 1.18 (0.84–1.64) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [65] Murtaugh et al. 2003 | 952 | 1205 | Processed meat | 1.18 (0.87–1.61) ♀ 1.23 (0.84–1.81) ♂ | No significant risk of CRC |

| [66] Kimura et al. 2007 | 782 | 793 | Processed meats | 1.15 (0.83–1.60) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [68] Nothlings et al. 2009 | 1009 | 1522 | Processed meat | 1.08 (0.89–1.39) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [69] Steinmetz and Potter 1993 | 220 | 438 | Processed meat | 1.03 (0.55–1.95)♂ 0.77 (0.35–1.68)♀ | No significant risk of CRC |

| [70] Franceschi et al. 1997 | 1225 | 4154 | Processed meat | 1.02 (0.89–1.24) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [71] Centozone 2009 | 119 | 119 | Processed meat | 1.01 | No significant risk of CRC |

| [72] Tiemersma et al. 2002 | 102 | 537 | Sausage | 0.90 (0.6–1.3) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [43] Macquart-Moulin 1986 | 399 | 399 | Charcuterie | 0.89 | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [80] Iscovich et al. 1992 | 110 | 220 | Processed meat | 0.43 (0.21–0.89) | Significantly ↓ risk of CRC |

| [45] Nowell et al. 2002 | 157 | 380 | Sausage and bacon | - | Significantly ↑ bacon consumption in cases group |

| Author | Sample size | Colorectal Cancer Cases | Description of Processed Meat | Relative Risk (CI) | Findings |

| [48] Wu et al. 2006 | 14,032 | 581 ‡ | Sausage, salami, bologna | 1.52 (1.12–2.08) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [49] English et al. 2004 | 37,112 | 284 | Salami, continental sausages, sausages or frankfurters, bacon, ham | 1.50 (1.1–2.0) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [56] Takachi et al. 2011 | 98,514 | 1145 | Processed meat | 1.27 (0.95,1.71) ♂ 1.19 (0.82,1.74) ♀ | No significant risk of CRC |

| [57] Sato et al. 2006 | 47,605 | 358 | Ham or sausage | 0.91 (0.61–1.35) | No significant risk of CRC |

| [59] Knekt et al. 1999 | 9985 | 73 | Nitrite | 0.74 (0.34–1.63) | No significant risk of CRC |

| Author | Cases (n =) | Controls (n =) | Description of Processed Meat | Relative Risk (CI) | Findings |

| [53] Lohsoonthorn et al. 1995 | 279 | 279 | Bacon | 12.49 (1.68–269.1) | Significantly ↑ bacon consumption in cases group |

| [34] Tajima and Tomina 1985 | 93 | 186 | Ham and sausage | 2.87 | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [36] Haenszel et al. 1973 | 179 | 357 | Sausage and other processed pork | 2.3Ϟ 1.77 Ф 2.7҂ | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [35] Levi et al. 2004 | 323 | 1271 | Ham salami sausage | 2.53 (1.50–4.27) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [38] Bidoli et al. 1992 | 123¥ 125₸ | 699 | Salami and sausages | 1.8¥ 1.9₸ | Sig ↑¥ but not ₸ |

| [37] Young and Wolf 1988 | 152ⱡ 201‡ | 618 | Processed lunch meat | 1.85 (1.33–2.58) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [42] De Verdier et al. 1991 | 559 | 505 | Bacon | 1.3 (0.8–1.9)¥ 1.7 (1.1–2.8)₸ | Sig ↑ ¥ but not ₸ |

| [39] Navarro et al. 2003 | 287 | 566 | Cold cuts and sausages | 1.64 (1.16–2.32) | Significantly ↑ risk of CRC |

| [62] Dales et al. 1978 | 99 | 280 | Nitrite treated meats | 1.22 | No significant risk of CRC |

| [43] Macquart-Moulin 1986 | 399 | 399 | Charcuterie | 0.89 | No significant risk of CRC |

| [80] Iscovich et al. 1992 | 110 | 220 | Delicatessen meat | 0.43 (0.21–0.89) | Significantly ↓ risk of CRC |

| [45] Nowell et al. 2002 | 157 | 380 | Sausage and bacon | - | Significantly ↑ bacon consumption in cases group |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crowe, W.; Elliott, C.T.; Green, B.D. A Review of the In Vivo Evidence Investigating the Role of Nitrite Exposure from Processed Meat Consumption in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112673

Crowe W, Elliott CT, Green BD. A Review of the In Vivo Evidence Investigating the Role of Nitrite Exposure from Processed Meat Consumption in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients. 2019; 11(11):2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112673

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrowe, William, Christopher T. Elliott, and Brian D. Green. 2019. "A Review of the In Vivo Evidence Investigating the Role of Nitrite Exposure from Processed Meat Consumption in the Development of Colorectal Cancer" Nutrients 11, no. 11: 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112673

APA StyleCrowe, W., Elliott, C. T., & Green, B. D. (2019). A Review of the In Vivo Evidence Investigating the Role of Nitrite Exposure from Processed Meat Consumption in the Development of Colorectal Cancer. Nutrients, 11(11), 2673. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11112673