First Trimester Serum Copper or Zinc Levels, and Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Method and Data Collection

2.3. Definition of the Studied Outcome

2.4. Serum Copper and Zinc Determination

2.5. Statistical Analyses

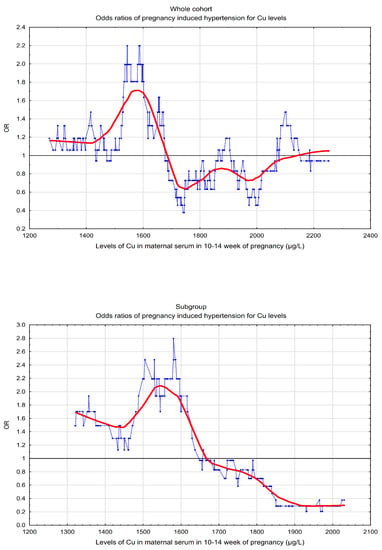

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maggini, S.; Pierre, A.; Calder, P.C. Immune Function and Micronutrient Requirements Change over the Life Course. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.; Herulah, U.N.; Prasad, A.; Petocz, P.; Samman, S. Zinc Status of Vegetarians during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies and Meta-Analysis of Zinc Intake. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4512–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, P.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Moreyra, A.E.; Korichneva, I.L. Zinc and cardiovascular disease. Nutrition 2010, 26, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, R.; Kim, M.J.; Sohn, I.; Kim, S.; Kim, I.; Ryu, J.M.; Choi, H.J.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, S.K.; Yu, J.; et al. Serum Trace Elements and Their Associations with Breast Cancer Subgroups in Korean Breast Cancer Patients. Nutrients 2018, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uriu-Adams, J.Y.; Keen, C.L. Copper, oxidative stress, and human health. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005, 26, 268–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołonciej, M.; Milewska, E.; Roszkowska-Jakimiec, W. Trace elements as an activator of antioxidant enzymes. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw. 2016, 70, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederickson, C.J.; Koh, J.Y.; Bush, A.I. The neurobiology of zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaye, K.M.; Yahaya, I.A.; Lindmark, K.; Henein, M.Y. Serum selenium and ceruloplasmin in nigerians with peripartum cardiomyopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 7644–7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetke, L.M.; Chow-Johnson, H.S.; Chow, C.K. Copper: Toxicological relevance and mechanisms. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 1929–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, H.D.; Gill, C.A.; Kurlak, L.O.; Seed, P.T.; Hesketh, J.E.; Méplan, C.; Schomburg, L.; Chappell, L.C.; Morgan, L.; Poston, L.; et al. Association between maternal micronutrient status, oxidative stress, and common genetic variants in antioxidant enzymes at 15 weeks’ gestation in nulliparous women who subsequently develop preeclampsia. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 78, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeeinia, A.; Tabandeh, A.; Khajeniazi, S.; Marjani, A.J. Serum copper, zinc and lipid peroxidation in pregnant women with preeclampsia in gorgan. Open Biochem. J. 2014, 8, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draganovic, D.; Lucic, N.; Jojic, D. Oxidative Stress Marker and Pregnancy Induced Hypertension. Med. Arch. 2016, 70, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakou, K.; Evangelou, E.; Papatheodorou, S.I. Genetic and non-genetic risk factors for pre-eclampsia: Umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 51, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaerts, D.; Faes, E.; Cos, P.; Briedé, J.J.; Gyselaers, W.; Cornette, J.; Gorbanev, Y.; Bogaerts, A.; Spaanderman, M.; Van Craenenbroeck, E.; et al. Oxidative stress in healthy pregnancy and preeclampsia is linked to chronic inflammation, iron status and vascular function. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.M.; Kramer, M.S.; Platt, R.W.; Basso, O.; Evans, R.W.; Kahn, S.R. The association between maternal antioxidant levels in midpregnancy and preeclampsia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, e1–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Li, B.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. High serum copper level is associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia in Asians: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Res. 2017, 39, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Kang, Y.; Zhang, M. A meta-analysis of copper level and risk of preeclampsia: Evidence from 12 publications. Biosci. Rep. 2016, 36, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shen, X.; Zhang, D. The Relationship between Serum Zinc Level and Preeclampsia: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7806–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, J. Association between zinc level and the risk of preeclampsia: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2016, 293, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Y. Comparison of serum zinc, calcium, and magnesium concentrations in women with pregnancy-induced hypertension and healthy pregnant women: A meta-analysis. Hypertens. Pregnancy 2016, 35, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwuja, E.I.; Ejikeme, B.N.; Ugwu, N.C.; Obeka, N.C.; Akubugwo, E.I.; Obidoa, O. Comparison of Plasma Copper, Iron and Zinc Levels in Hypertensive and Non-hypertensive Pregnant Women in Abakaliki, South Eastern Nigeria. Pak. J. Nutr. 2010, 9, 1136–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Yu, J.Y.; Jenkins, A.J.; Nankervis, A.J.; Hanssen, K.F.; Henriksen, T.; Lorentzen, B.; Garg, S.K.; Menard, M.K.; Hammad, S.M.; et al. Trace elements as predictors of preeclampsia in type 1 diabetic pregnancy. Nutr. Res. 2015, 35, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jameil, N.; Tabassum, H.; Al-Mayouf, H.; Aljohar, H.I.; Alenzi, N.D.; Hijazy, S.M.; Khan, F.A. Analysis of serum trace elements-copper, manganese and zinc in preeclamptic pregnant women by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry: A prospective case controlled study in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2014, 7, 1900–1910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duhig, K.; Vandermolen, B.; Shennan, A. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of pre-eclampsia. F1000Research 2018, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, R.; Sun, J.; Yoo, H.; Kim, S.; Cho, Y.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.W.; Chung, J.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Lee, S.Y. A Prospective Study of Serum Trace Elements in Healthy Korean Pregnant Women. Nutrients 2016, 8, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Bu, J. Relationship between Selected Serum Metallic Elements and Obesity in Children and Adolescent in the U.S. Nutrients 2017, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.M.; Wu, X.Y.; Huang, K.; Yan, S.Q.; Li, Z.J.; Xia, X.; Pan, W.J.; Sheng, J.; Tao, Y.R.; Xiang, H.Y.; et al. Trace element profiles in pregnant women’s sera and umbilical cord sera and influencing factors: Repeated measurements. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Abdennebi, M.; Ben Mami, F.; Ghanem, A.; Azzabi, S.; Hedhili, A.; Zouari, B.; Achour, A.; Guemira, F. Serum copper levels in obesity: A study of 32 cases. Tunis. Med. 2001, 79, 370–373. [Google Scholar]

- Olusi, S.; Al-Awadhi, A.; Abiaka, C.; Abraham, M.; George, S. Serum copper levels and not zinc are positively associated with serum leptin concentrations in the healthy adult population. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2003, 91, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerlikaya, F.H.; Toker, A.; Arıbaş, A. Serum trace elements in obese women with or without diabetes. Indian J. Med. Res. 2013, 137, 339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Kocyigit, A.; Erel, O.; Gur, S. Effects of tobacco smoking on plasma selenium, zinc, copper and iron concentrations and related antioxidative enzyme activities. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 34, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, F.M.; Pakdel, F.G. Serum Level of Some Minerals during Three Trimesters of Pregnancy in Iranian Women and Their Newborns: A Longitudinal Study. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2014, 29, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, G.J.; Watson, A.L.; Hempstock, J.; Skepper, J.N.; Jauniaux, E. Uterine glands provide histiotrophic nutrition for the human fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 2954–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hod, T.; Cerdeira, A.S.; Karumanchi, S.A. Molecular Mechanisms of Preeclampsia. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a023473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Lubiński, J. Serum Selenium Level in Early Healthy Pregnancy as a Risk Marker of Pregnancy Induced Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Lubiński, J. Can Serum Iron Concentrations in Early Healthy Pregnancy Be Risk Marker of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension? Nutrients 2019, 11, 1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, M.E.; Ulas, T.; Dal, M.S.; Eren, M.A.; Aydogan, H.; Yalcin, S.; Camuzcuoglu, A.; Hilali, N.G.; Aksoy, N.; Buyukhatipoglu, H. Oxidative stress parameters and ceruloplasmin levels in patients with severe preeclampsia. Clin. Ter. 2013, 164, e83–e87. [Google Scholar]

- Blumfield, M.L.; Hure, A.J.; Macdonald-Wicks, L.; Smith, R.; Collins, C.E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of micronutrient intakes during pregnancy in developed countries. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziaei, S.; Janghorban, R.; Shariatdoust, S.; Faghihzadeh, S. The effects of iron supplementation on serum copper and zinc levels in pregnant women with high-normal hemoglobin. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2008, 100, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.; Lind, P.M.; Lindgren, C.; Ingelsson, E.; Mahajan, A.; Morris, A.; Lind, L. Genome-wide association study of toxic metals and trace elements reveals novel associations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 4739–4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Normotensives (n = 363) * | Cases (n = 121) * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Mean (SD) or n (%) | p ** | |

| Maternal age (years) | 35.1 (4.0) | 35.1 (4.2) | 0.907 |

| Maternal age (range) | (22–45) | (19–45) | |

| Gestational age at recruitment (weeks) | 12.3 (0.8) | 11.6 (0.8) | 1.97 × 10−16 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m²) | 25.0 (4.4) | 26.8 (5.4) | 0.003 |

| Primiparous | 141 (38.84%) | 56 (46.28%) | 0.149 |

| Prior PE | − | 3 | − |

| Prior PIH/PE • | 2 (0.55%) | 13 (10.74%) | <0.001 |

| ART • | 18 (4.96%) | 11 (9.09%) | 0.097 |

| Women who have never smoked | 302 (83.20%) | 92 (76.03%) | 0.080 |

| Pack-years of smokers *** | 19.3 (32.5) | 21.2 (32.3) | 0.748 |

| Multivitamins in II-III trimester | 184 (50.69%) | 50 (41.32%) | 0.074 |

| Education <12 years (for available data) | 28 (9.18%) | 20 (19.05%) | 0.007 |

| Lower financial status (1-2-3) | 46 (32.6%) | 31 (49.2%) | 0.002 # |

| Village | 110 (30.4%) | 30 (25.0%) | 0.585 # |

| Outcomes | |||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 38.7 (1.8) | 37.99 (2.6) | 0.011 |

| Newborn birthweight (g) | 3385.3 (546.8) | 3113.1 (785.4) | 0.0003 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) **** | 107.3 (11.4) | 158.3 (18.2) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) **** | 66.0 (8.8) | 100.2 (10.5) | <0.0001 |

| Preeclampsia | − | 15 | − |

| Gestational hypertension | − | 106 | − |

| GDM • | 73 (20.11%) | 23 (19.01%) | 0.792 |

| Biomarkers (µg/L) ** | Normotensives * | Cases * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p ** ** | |

| Normal BMI subgroup, n *** | 211 | 54 | |

| Copper | 1693.39 (275.70) | 1595.01 (255.24) | 0.008 |

| Zinc | 614.60 (93.75) | 615.40 (83.60) | 0.867 |

| Cu:Zn ratio | 2.81 (0.60) | 2.65 (0.60) | 0.037 |

| Quartile | Cu (µg/L) ! | Cases • | Controls • | Odds Ratios of PIH/GH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR * (95% CI:); p *** | AOR ** (95% CI:); p *** | ||||

| Whole cohort (PIH risk) | |||||

| Q1 | 883.61–1540.58 | 33 | 88 | 1.52 (0.83–2.76); 0.174 | 2.17 (1.14–4.16); 0.019 |

| Q2 | 1540.58–1733.78 | 37 | 84 | 1.78 (0.99–3.22); 0.056 | 2.39 (1.28–4.49); 0.007 |

| Q3 | 1733.78–1937.46 | 27 | 94 | 1.16 (0.63–2.16); 0.637 | 2.35 (0.71–2.57); 0.360 |

| Q4 | 1937.46–3956.76 | 24 | 97 | 1 | 1 |

| Whole cohort (GH risk) | |||||

| Q1 | 883.61–1541.95 | 30 | 76 | 1.60 (0.84–3.02); 0.150 | 2.36 (1.19–4.68); 0.015 |

| Q2 | 1541.95–1735.86 | 32 | 74 | 1.75 (0.93–3.30); 0.083 | 2.35 (1.20–4.60); 0.012 |

| Q3 | 1735.86–1937.46 | 23 | 83 | 1.12 (0.58–2.18); 0.735 | 1.27 (0.64–2.52); 0.503 |

| Q4 | 1937.46–3956.76 | 21 | 85 | 1 | 1 |

| Subgroup # | |||||

| Q1 | 969.60–1486.63 | 17 | 49 | 2.97 (1.14–7.75); 0.026 | 2.95 (1.05–8.27); 0.040 |

| Q2 | 1486.63–1667.50 | 18 | 48 | 3.21 (1.24–8.33); 0.016 | 4.05 (1.44–11.43); 0.008 |

| Q3 | 1667.50–1838.35 | 12 | 54 | 1.91 (0.70–5.19); 0.208 | 2.18 (0.75–6.39); 0.154 |

| Q4 | 1838.35–2500.75 | 7 | 60 | 1 | 1 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lewandowska, M.; Sajdak, S.; Marciniak, W.; Lubiński, J. First Trimester Serum Copper or Zinc Levels, and Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102479

Lewandowska M, Sajdak S, Marciniak W, Lubiński J. First Trimester Serum Copper or Zinc Levels, and Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Nutrients. 2019; 11(10):2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102479

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewandowska, Małgorzata, Stefan Sajdak, Wojciech Marciniak, and Jan Lubiński. 2019. "First Trimester Serum Copper or Zinc Levels, and Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension" Nutrients 11, no. 10: 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102479

APA StyleLewandowska, M., Sajdak, S., Marciniak, W., & Lubiński, J. (2019). First Trimester Serum Copper or Zinc Levels, and Risk of Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension. Nutrients, 11(10), 2479. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102479