Avocado Fruit on Postprandial Markers of Cardio-Metabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Dose Response Trial in Overweight and Obese Men and Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

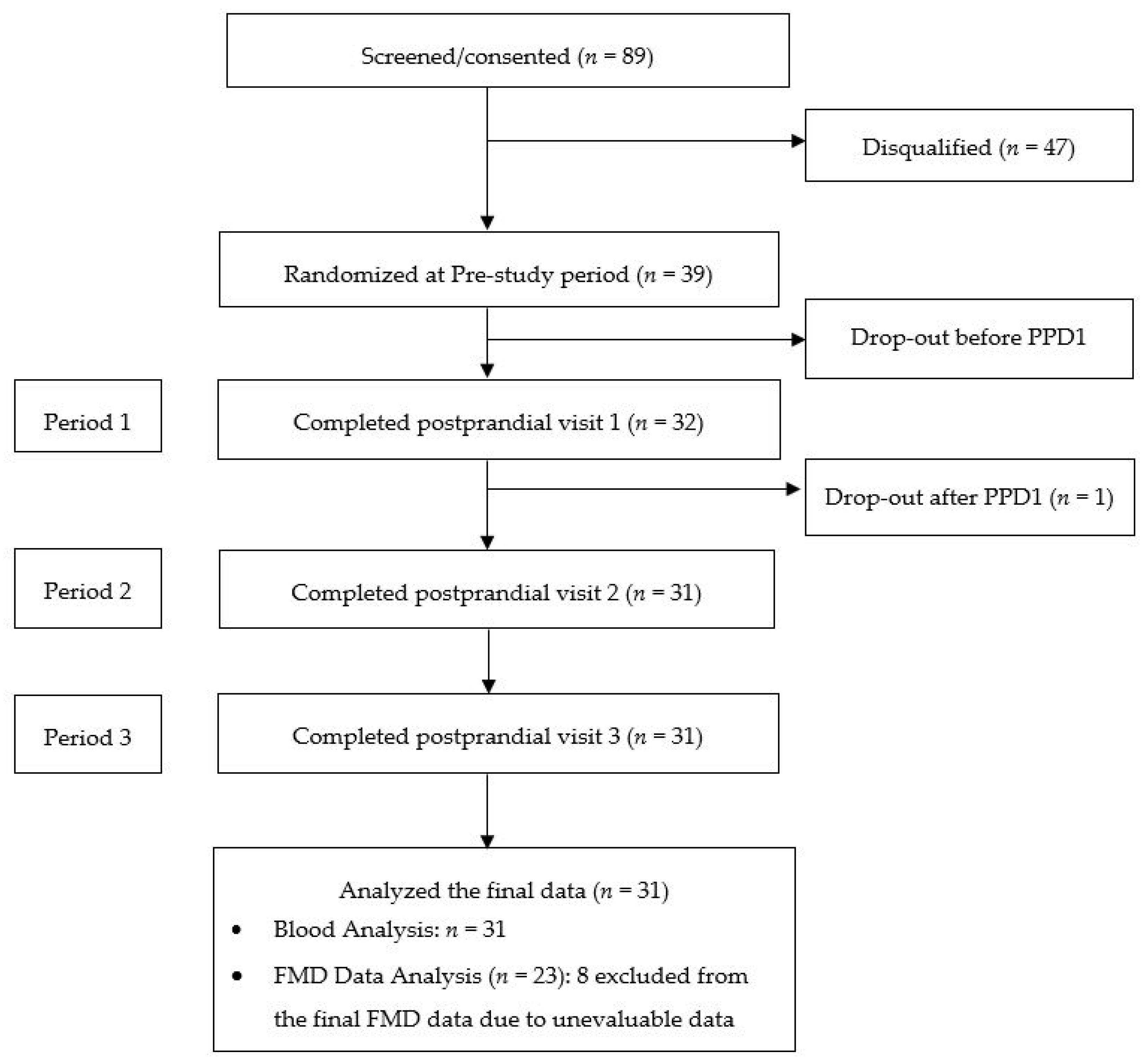

2.1. Subjects and Consort Flow Diagram

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Design

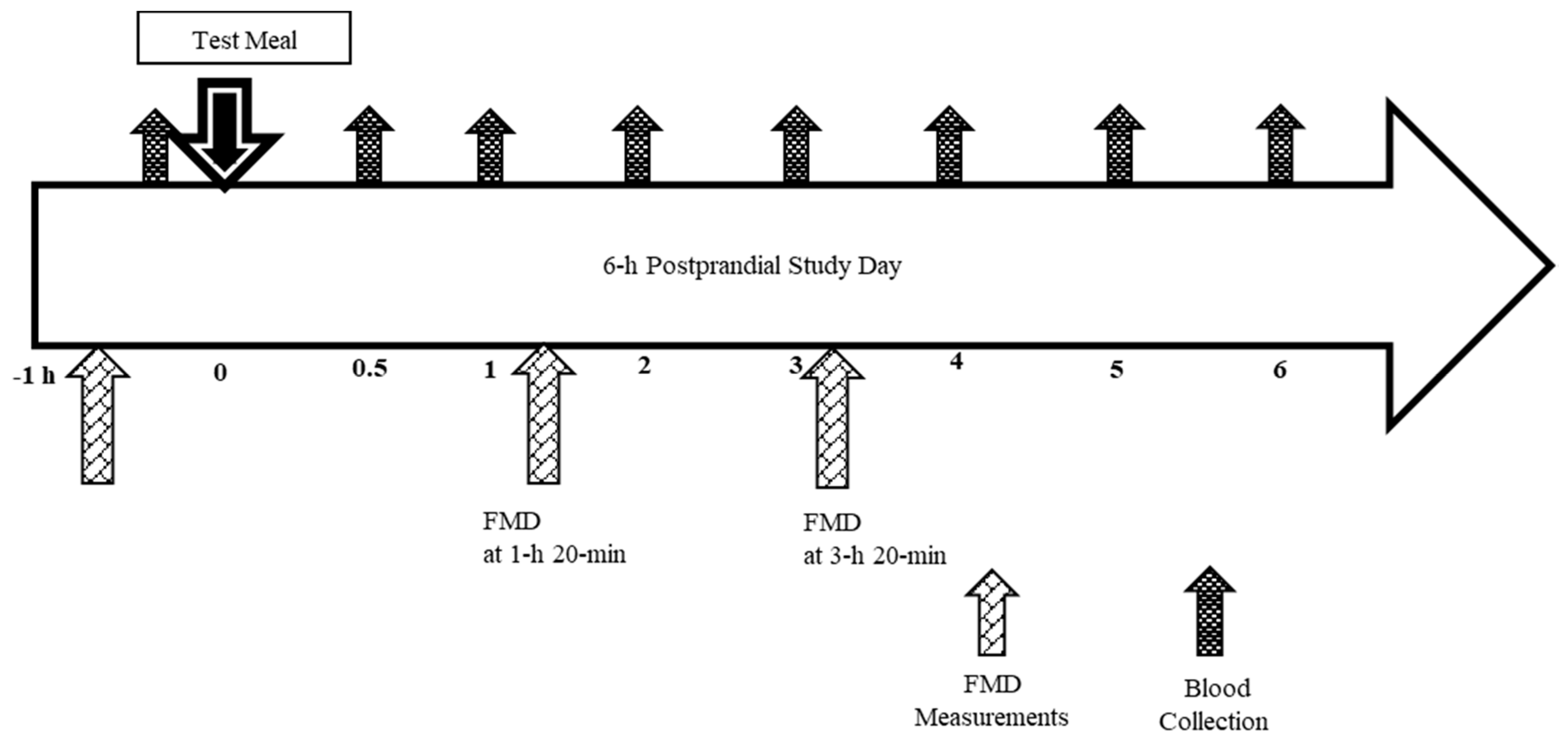

2.5. Study Timeline and Procedures

2.6. Test Meals

2.7. Height and Weight

2.8. Metabolic Responses

2.9. Flow Mediated Dilation (FMD)

2.10. Sample Size

2.11. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

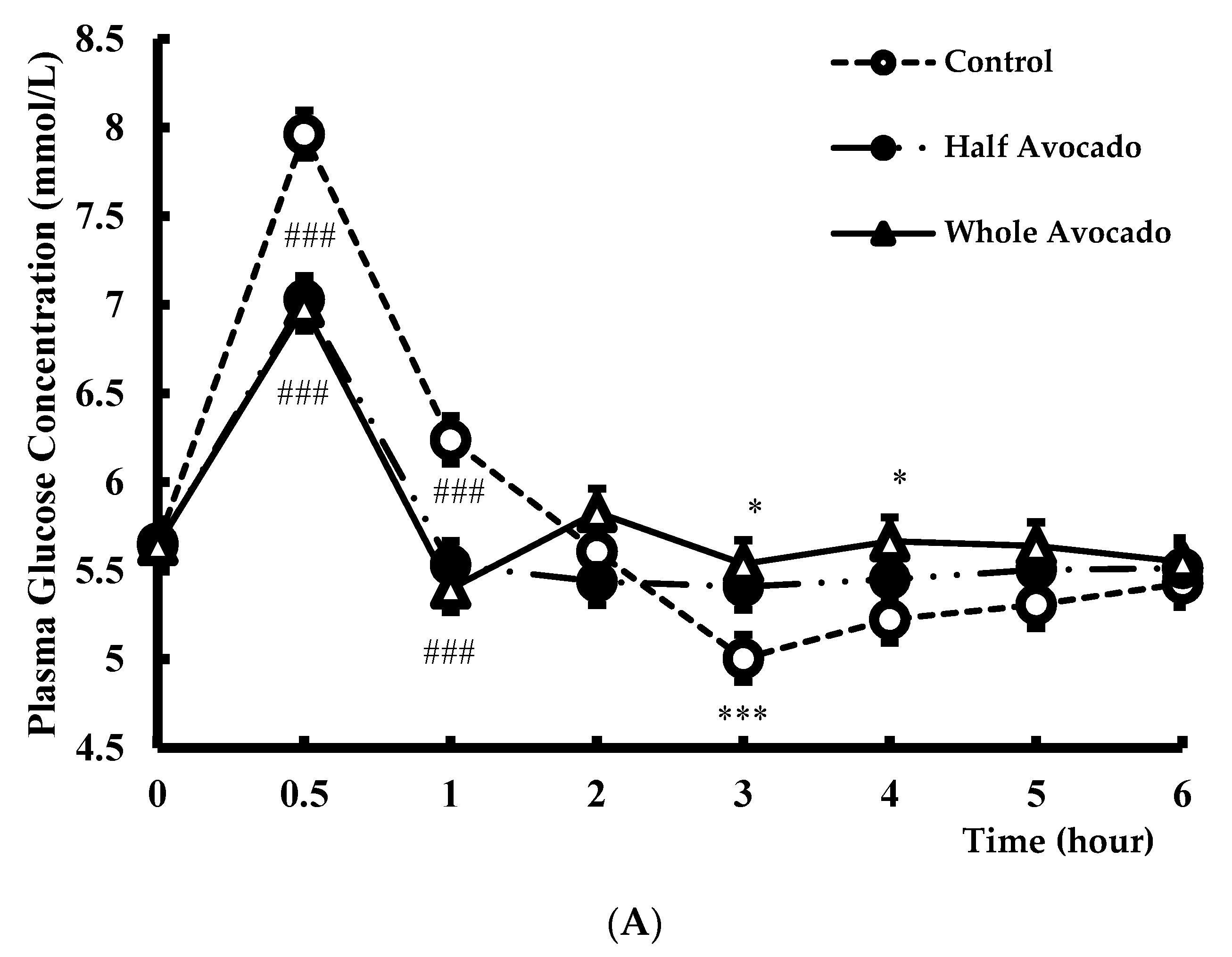

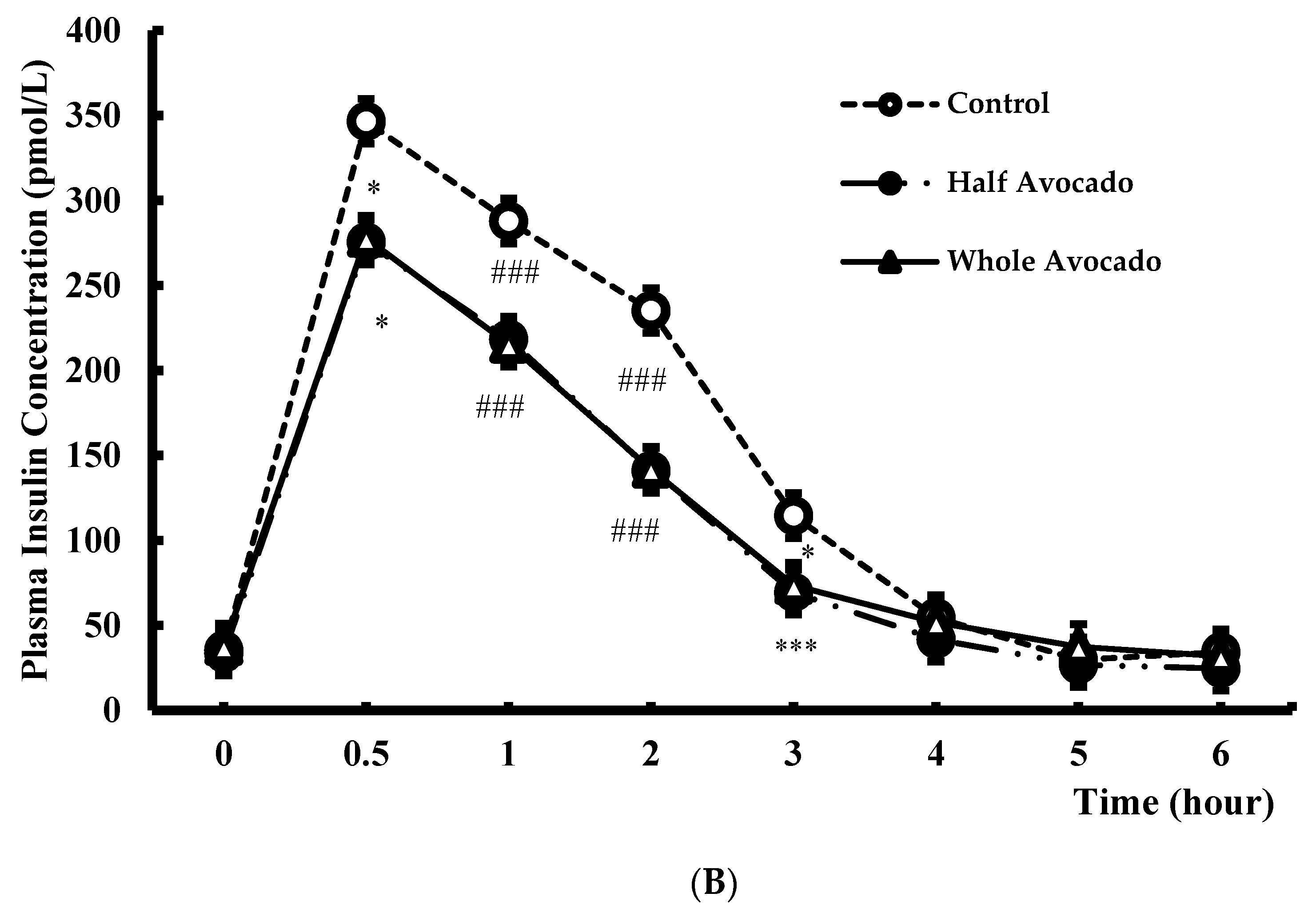

3.2. Glucose and Insulin

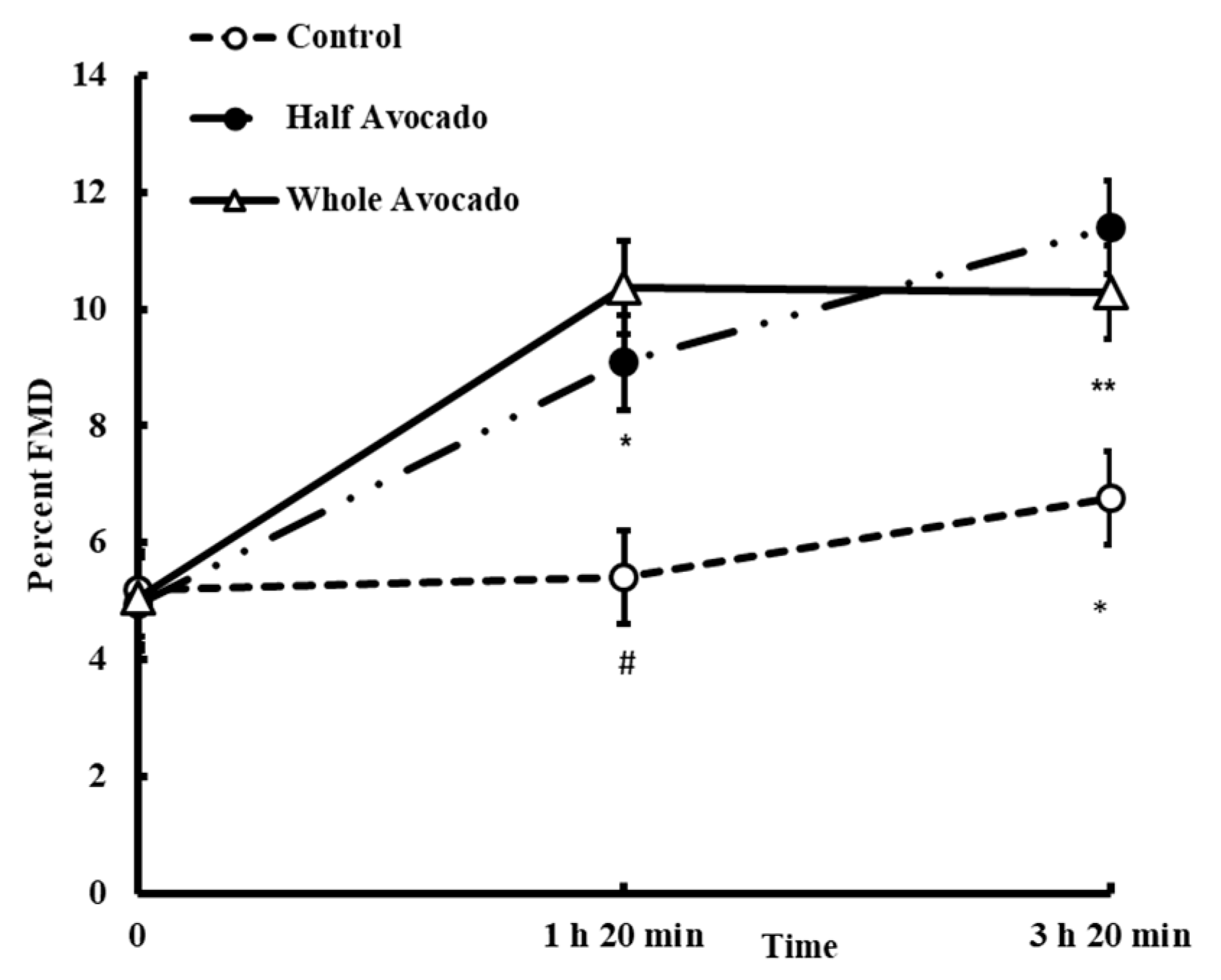

3.3. Flow Mediated Vasodilation (FMD)

3.4. Plasma Lipoprotein Particle Number and Size Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

3.5. Inflammatory and Oxidative Stress Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Hruby, A.; Bernstein, A.M.; Ley, S.H.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Frank, B. Saturated Fats Compared With Unsaturated Fats and Sources of Carbohydrates in Relation to Risk of Coronary Heart Disease: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 1538–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, L.S.; Li, L.; Ford, E.S.; Liu, S. Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: An ecologic assessment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.F.; Vethakkan, S.R.; Nesaretnam, K.; Sanders, T.A.B.; Teng, K.-T. Adverse effects on insulin secretion of replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrate but not with monounsaturated fat: A randomized controlled trial in centrally obese subjects. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2016, 10, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, R.; Clemente, G.; Cipriano, D.; Luongo, D.; Viscovo, D.; Patti, L.; Di Marino, L.; Giacco, A.; Naviglio, D.; Bianchi, M.A.; et al. Effects of the regular consumption of wholemeal wheat foods on cardiovascular risk factors in healthy people. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 20, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacco, R.; Costabile, G.; Della Pepa, G.; Anniballi, G.; Griffo, E.; Mangione, A.; Cipriano, P.; Viscovo, D.; Clemente, G.; Landberg, R.; et al. A whole-grain cereal-based diet lowers postprandial plasma insulin and triglyceride levels in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2014, 24, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafeiadou, K.; Weech, M.; Altowaijri, H.; Todd, S.; Yaqoob, P.; Jackson, K.; Lovegrove, J. Replacement of saturated with unsaturated fats had no impact on vascular function but beneficial effects on lipid biomarkers, E-selectin, and blood pressure: Results from the randomized, controlled Dietary Intervention and VAScular function (DIVAS) study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 102, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Pearson, T.A.; Wan, Y.; Hargrove, R.L.; Moriarty, K.; Fishell, V.; Al, K.E.T. High-monounsaturated fatty acid diets lower both plasma cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 70, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, F.; Micha, R.; Wu, J.H.Y.; de Oliveira Otto, M.C.; Otite, F.O.; Abioye, A.I.; Mozaffarian, D. Effects of Saturated Fat, Polyunsaturated Fat, Monounsaturated Fat, and Carbohydrate on Glucose-Insulin Homeostasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Feeding Trials. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, F.; Appel, L.; Moore, T.; Obarzanek, E.; Vollmer, W.; Svetkey, L.; Bray, G.; Vogt, T.; Cutler, J.; Windhauser, M.; et al. A dietary approach to prevent hypertension: A review of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study. Clin. Cardiol. 1999, 22 (Suppl. 7), III6–III10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; a Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlich, M.J. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Health; Human Services; U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans; U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Dreher, M.L.; Davenport, A.J. Hass avocado composition and potential health effects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bordi, P.L.; Fleming, J.A.; Hill, A.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.M. Effect of a moderate fat diet with and without avocados on lipoprotein particle number, size and subclasses in overweight and obese adults: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerman-Garber, I.; Ichazo-Cerro, S.; Zamora-González, J.; Cardoso-Saldaña, G.; Posadas-Romero, C. Effect of a high-monounsaturated fat diet enriched with avocado in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 1994, 17, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wien, M.; Haddad, E.; Oda, K.; Sabaté, J. A randomized 3 × 3 crossover study to evaluate the effect of Hass avocado intake on post-ingestive satiety, glucose and insulin levels, and subsequent energy intake in overweight adults. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Bantle, J.P.; Henry, R.R.; Coulston, A.M.; Griver, K.A.; Raatz, S.K.; Brinkley, L.; Chen, Y.D.; Grundy, S.M.; Huet, B.A.; et al. Effects of varying carbohydrate content of diet in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1994, 271, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.C.; Porter, K.E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2013, 10, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokken, B.B. The Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: Beyond Blood Pressure and Lipids. Diabetes Spectr. 2008, 21, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, H.; Motoyama, T.; Hirashima, O.; Hirai, N.; Miyao, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Kugiyama, K.; Ogawa, H.; Yasue, H. Hyperglycemia rapidly suppresses flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation of brachial artery. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 34, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriello, A.; Taboga, C.; Tonutti, L.; Quagliaro, L.; Piconi, L.; Bais, B.; Da Ros, R.; Motz, E. Evidence for an independent and cumulative effect of postprandial hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia on endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress generation: Effects of short- and long-term simvastatin treatment. Circulation 2002, 106, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.; Bell, D. Postprandial hyperglycemia/hyperlipidemia (postprandial dysmetabolism) is a cardiovascular risk factor. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007, 100, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Freeman, B. Postprandial metabolic events and fruit-derived phenolics: A review of the science. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, S1–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, S.; Verga, S.; Tranchina, M.R.; Cottone, S.; Cerasola, G. Effects of hypocaloric very-low-carbohydrate diet vs. Mediterranean diet on endothelial function in obese women. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 39, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rallidis, L.; Lekakis, J.; Kolomvotsou, A.; Zampelas, A.; Vamvakou, G.; Efstathiou, S.; Dimitriadis, G.; Raptis, S.A.; Kremastinos, D.T. Close adherence to a Mediterranean diet improves endothelial function in subjects with abdominal obesity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corretti, M.C.; Anderson, T.J.; Benjamin, E.J.; Celermajer, D.; Charbonneau, F.; Creager, M.A.; Deanfield, J.; Drexler, H.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Herrington, D.; et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: A report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbis, A.; Perdreau, S.; Vincent-Baudry, S.; Charbonnier, M.; Bernard, M.C.; Raccah, D.; Senft, M.; Lorec, A.M.; Defoort, C.; Portugal, H.; et al. Glycemic and insulinemic meal responses modulate postprandial hepatic and intestinal lipoprotein accumulation in obese, insulin-resistant subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, K.C.; Galant, R.; Samuel, P.; Tesser, J.; Witchger, M.S.; Ribaya-Mercado, J.D.; Blumberg, J.B.; Geohas, J. Effects of consuming foods containing oat beta-glucan on blood pressure, carbohydrate metabolism and biomarkers of oxidative stress in men and women with elevated blood pressure. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenward, M.; Roger, J. Small sample inference for fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Biometrics 1997, 53, 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenward, M.G.; Roger, J.H. An improved approximation to the precision of fixed effects from restricted maximum likelihood. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2009, 53, 2583–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenward, M. A Method for Comparing Profiles of Repeated Measurements. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1987, 36, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilversmit, D. Atherogenesis: A postprandial phenomenon. Circulation 1979, 60, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meigs, J.B.; Nathan, D.M.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Wilson, P.W.F. Fasting and postchallenge glycemia and cardiovascular disease risk: The Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comment in Diabetes Care. American Diabetes Association Postprandial blood glucose. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Diabetes Policy Group. A desktop guide to type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet. Med. 1999, 16, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceriello, A.; Esposito, K.; Piconi, L.; Ihnat, M.A.; Thorpe, J.E.; Testa, R.; Boemi, M.; Giugliano, D. Oscillating glucose is more deleterious to endothelial function and oxidative stress than mean glucose in normal and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2008, 57, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Keefe, J.H.; Gheewala, N.M.; O’Keefe, J.O. Dietary strategies for improving post-prandial glucose, lipids, inflammation, and cardiovascular health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceriello, A. The post-prandial state and cardiovascular disease: Relevance to diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2000, 16, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 2001, 414, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, B. Post prandial plasma glucose level less than the fasting level in otherwise healthy individuals during routine screening. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2006, 21, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, E. Postprandial peaks as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease: Epidemiological perspectives. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 2002, 129, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, R.A.; Evans, M.L.; Ellis, G.R.; Graham, J.; Morris, K.; Jackson, S.K.; Lewis, M.J.; Rees, A.; Frenneaux, M.P. The relationships between post-prandial lipaemia, endothelial function and oxidative stress in healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis 2001, 154, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slyper, A.H. A fresh look at the atherogenic remnant hypothesis. Lancet 1992, 340, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, M.; Maruhashi, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Iwamoto, Y.; Iwamoto, A.; Oda, N.; Kishimoto, S.; Matsui, S.; Aibara, Y.; Hidaka, T.; et al. Relationship between serum triglyceride levels and endothelial function in a large community-based study. Atherosclerosis 2016, 249, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, K.; Clark, J.; Griffiths, H.R. An almond-enriched diet increases plasma α-tocopherol and improves vascular function but does not affect oxidative stress markers or lipid levels. Free Radic. Res. 2014, 48, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacroix, S.; Des Rosiers, C.; Gayda, M.; Nozza, A.; Thorin, É.; Tardif, J.-C.; Nigam, A. A single Mediterranean meal does not impair postprandial flow-mediated dilatation in healthy men with subclinical metabolic dysregulations. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 41, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, R.A.; Corretti, M.C.; Plotnick, G.D. The postprandial effect of components of the Mediterranean diet on endothelial function. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 36, 1455–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzur, R.; Cohen, H.; Kamari, Y.; Shaish, A.; Harats, D. Triglycerides and HDL cholesterol: Stars or second leads in diabetes? Diabetes Care 2009, 32, S373–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontush, A. HDL particle number and size as predictors of cardiovascular disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, S.; Williams, P.T.; Krauss, R.M. Effects of a very high saturated fat diet on LDL particles in adults with atherogenic dyslipidemia: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, A.; Bonanome, A.; Grundy, S.; Zhang, Z.; Unger, R. Comparison of a high-carbohydrate diet with a high-monounsaturated-fat diet in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, R.M. Dietary and genetic probes of atherogenic dyslipidemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 2265–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willey, J.Z.; Rodriguez, C.J.; Carlino, R.F.; Moon, Y.P.; Paik, M.C.; Boden-Albala, B.; Sacco, R.L.; Ditullio, M.R.; Homma, S.; Elkind, M.S.V. Race-ethnic differences in the association between lipid profile components and risk of myocardial infarction: The Northern Manhattan Study. Am. Heart J. 2011, 161, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwa, K.; Lyons, J.G.; Carrington, M.J.; Lecour, S.; Marais, A.D.; Raal, F.J.; Stewart, S. Different lipid profiles according to ethnicity in the Heart of Soweto study cohort of de novo presentations of heart disease: Cardiovascular topics. Cardiovasc. J. Afr. 2012, 23, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, G.; Clark, L.; Tang, A.; Marcovina, S.; Grundy, S.; Cohen, J. Hepatic lipase activity is lower in African American men than in white American men: Effects of 5’ flanking polymorphism in the hepatic lipase gene (LIPC). J. Lipid Res. 1998, 39, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, G.; Teo, K.K.; Islam, S.; McQueen, M.J.; Pais, P.; Wang, X.; Sato, H.; Lang, C.C.; Sitthi-Amorn, C.; Pandey, M.R.; et al. Lipid profile, plasma apolipoproteins, and risk of a first myocardial infarction among Asians: An analysis from the INTERHEART Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, D.J.; Judd, J.T.; Clevidence, B.A.; Tracy, R.P. Dietary fatty acids affect plasma markers of inflammation in healthy men fed controlled diets: A randomized crossover study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 79, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaram, S.; Connell, K.M.; Sabaté, J. Effect of almond-enriched high-monounsaturated fat diet on selected markers of inflammation: A randomised, controlled, crossover study. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Teno, C.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; Delgado-Lista, J.; Yubero-Serrano, E.M.; García-Ríos, A.; Marín, C.; Gómez, P.; Jiménez-Gómez, Y.; Camargo, A.; Rodríguez-Cantalejo, F.; et al. Dietary fat modifies the postprandial inflammatory state in subjects with metabolic syndrome: The LIPGENE study. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control Meal | Half Avocado Meal | Whole Avocado Meal | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 637.4 | 617.6 | 642.3 |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 120.6 | 78.37 | 80.7 |

| Sugar (g) | 59.4 | 26.5 | 25.5 |

| Fiber (g) | 4.9 | 8.6 | 13.1 |

| Protein (g) | 18.4 | 18.2 | 16.7 |

| Fat (g) | 9.9 | 27.3 | 30.7 |

| Saturated fat (g) | 4.9 | 11.3 | 8.6 |

| Trans fat (g) | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| Monounsaturated fat (g) | 2.1 | 10.8 | 15.8 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (g) | 1.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Breakfast Items | Control Meal | Half Avocado Meal | Whole Avocado Meal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hass Avocado, fresh | 0 | 68 | 136 |

| Bagel, plain † | 99 | 68 | 65 |

| Cream Cheese, fat free ‡ | 40 | 55 | 35 |

| Cucumber without skin | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Romaine lettuce | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Butter, unsalted § | 8 | 18 | 10 |

| Honeydew melon | 90 | 60 | 60 |

| Instant oatmeal (maple and brown sugar) || | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Brown sugar | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Unsweetened lemonade mix ¶ | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| White sugar | 20 | 5 | 5 |

| Water « | 310 | 304 | 310 |

| Variable | Total Subjects (n = 31) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 37.9 ± 10.3 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.0 ± 2.4 | |

| Mid-point waist circumference (cm) | 92.9 ± 10.1 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 110.7 ± 8.0 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.9 ± 7.5 | |

| Venous fasting glucose concentration (mmol/L) | 5.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Venous fasting insulin concentration (pmol/L) | 60.4 ± 20.8 | |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | Caucasian | 9 (29) |

| African-American | 13 (42) | |

| Asian | 5 (16) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (13) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Male | 15 (48) |

| Female | 16 (52) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) Categories ‡, n (%) | Overweight | 23 (74) |

| Obese I | 8 (26) | |

| NMR Analysis (Variable) | Control Meal | Whole Avocado Meal | p Value Con vs. Whole-A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chylomicron/VLDL Particle concentration (nmol/L) | Total | 49.2 ± 1.2 | 46.1 ± 1.3 | 0.02 |

| Large | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.36 | |

| Medium | 14.6 ± 0.8 | 13.3 ± 0.8 | 0.07 | |

| Small | 31.2 ± 1.3 | 29.0 ± 1.3 | 0.12 | |

| LDL Particle concentration (nmol/L) | Total | 962.5 ± 15.3 | 986.7 ± 15.7 | 0.07 |

| LDL, Large | 276.3 ± 9.7 | 277.8 ± 10.0 | 0.87 | |

| LDL and IDL, Medium | 232.2 ± 9.8 | 214.5 ± 10.2 | 0.11 | |

| LDL, Small | 456.0 ± 12.5 | 492.8 ± 13.0 | 0.009 | |

| HDL Particle concentration (nmol/L) | Total | 35.0 ± 0.2 | 35.2 ± 0.2 | 0.54 |

| Large | 8.2 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 0.06 | |

| Medium | 12.8 ± 0.3 | 13.9 ± 0.3 | 0.004 | |

| Small | 13.9 ± 0.3 | 12.9 ± 0.4 | 0.009 | |

| Average Particle size (mm) | VLDL | 47.8 ± 0.5 | 48.5 ± 0.5 | 0.17 |

| LDL | 20.7 ± 0.4 | 20.7 ± 0.4 | 0.94 | |

| HDL | 9.6 ± 0.01 | 9.6 ± 0.02 | 0.09 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, E.; Edirisinghe, I.; Burton-Freeman, B. Avocado Fruit on Postprandial Markers of Cardio-Metabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Dose Response Trial in Overweight and Obese Men and Women. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091287

Park E, Edirisinghe I, Burton-Freeman B. Avocado Fruit on Postprandial Markers of Cardio-Metabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Dose Response Trial in Overweight and Obese Men and Women. Nutrients. 2018; 10(9):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091287

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Eunyoung, Indika Edirisinghe, and Britt Burton-Freeman. 2018. "Avocado Fruit on Postprandial Markers of Cardio-Metabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Dose Response Trial in Overweight and Obese Men and Women" Nutrients 10, no. 9: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091287

APA StylePark, E., Edirisinghe, I., & Burton-Freeman, B. (2018). Avocado Fruit on Postprandial Markers of Cardio-Metabolic Risk: A Randomized Controlled Dose Response Trial in Overweight and Obese Men and Women. Nutrients, 10(9), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091287