Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reproducibility of the Mediterranean Islands Study Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Elderly Population Living in the Spanish Mediterranean

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Study Population

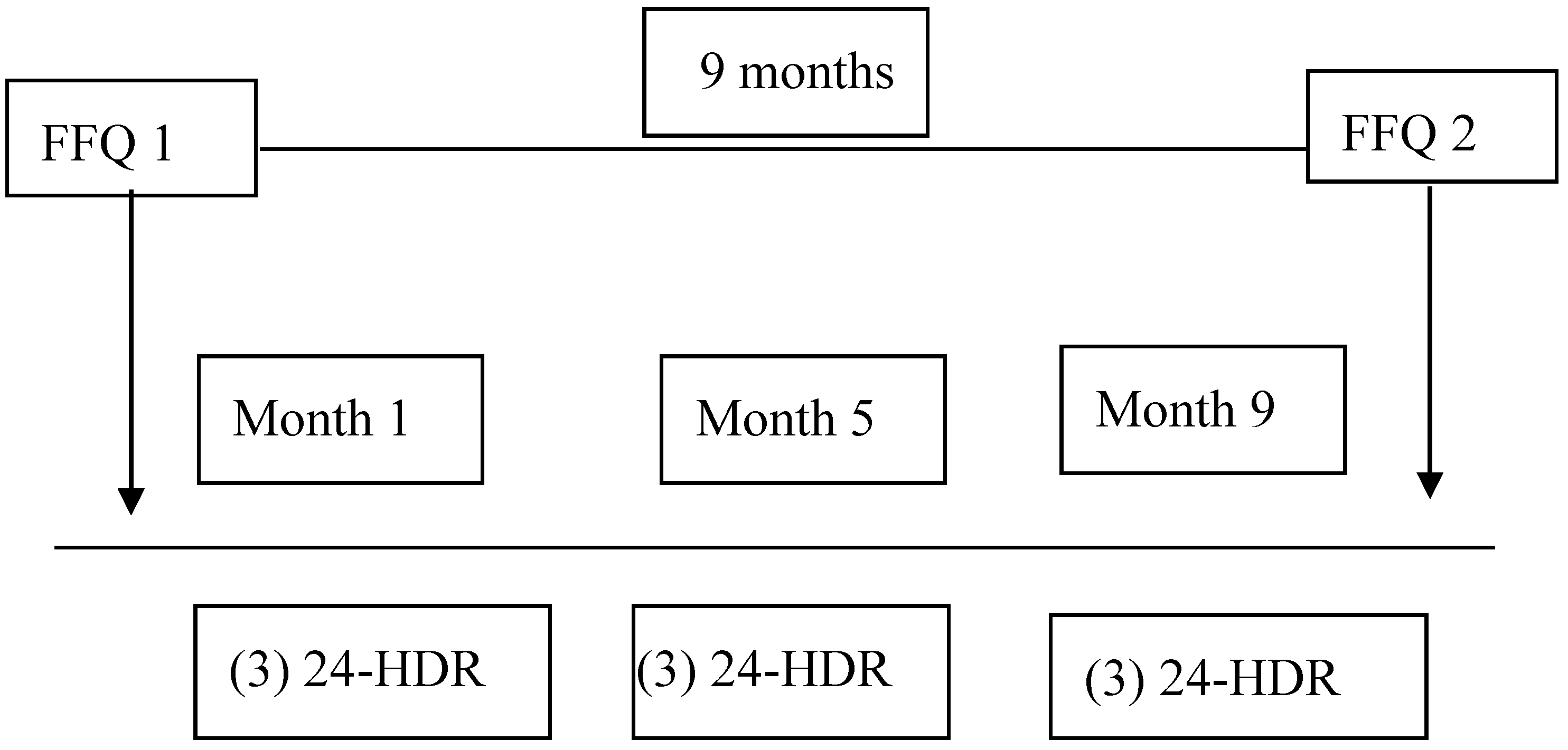

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Cross-Cultural Translation and Adaptation

2.3.1. Direct Translation

2.3.2. Back-Translation

2.3.3. Pilot Comprehension Test

2.4. Instruments and Diet Evaluation

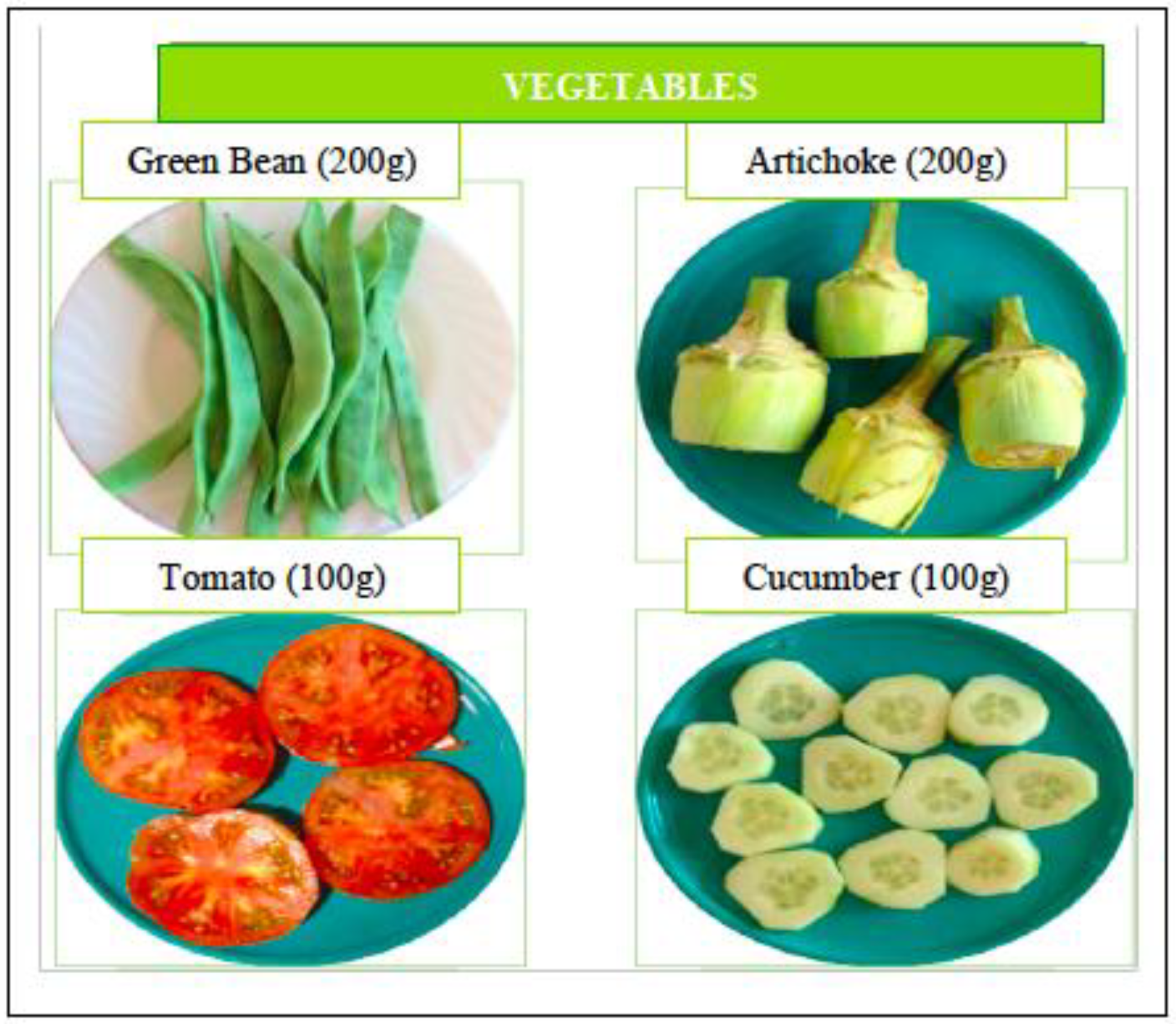

2.4.1. MEDIS-FFQ

2.4.2. 24-h Dietary Recall

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Calculation of Food Quantities and Nutrient Estimates

2.8. Statistical Analysis

2.8.1. Reproducibility

2.8.2. Validity

3. Results

3.1. Cross-Cultural Adaptation

3.2. Nutrient and Food Group Intakes

3.3. Reproducibility

3.4. Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Reproducibility

4.2. Validation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez, I.T.; Ballart, J.F.; Pastor, G.C.; Jordà, E.B.; Val, V.A. Validation of a short questionnaire on frequency of dietary intake: Reproducibility and validity. Nutr. Hosp. 2008, 23, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Lin, S.; Song, Q.; Lao, X.; Yu, I.T. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary consumption via the dietary pattern method in a Chinese rural population. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantin, J.; Latour, E.; Ferland-Verry, R.; Morales Salgado, S.; Lambert, J.; Faraj, M.; Nigam, A.; Morales Salgado, S.; Lambert, J.; Faraj, M.; Nigam, A. Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire focused on the Mediterranean diet for the Quebec population. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc Dis. 2016, 26, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroder, H.; Fito, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.; Ros, E.; Salaverría, I.; Fiol, M.; et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.; Craig, L.C.; Aucott, L.S.; Milne, A.C.; McNeill, G. Repeatability and validity of a food frequency questionnaire in free-living older people in relation to cognitive function. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2008, 12, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Hong, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Lai, Y.; Sun, L.; Xu, F. Reproducibility and validity of an FFQ developed for adults in Nanjing, China. Br. J. Nutr. 2016, 115, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eysteinsdottir, T.; Thorsdottir, I.; Gunnarsdottir, I.; Steingrimsdottir, L. Assessing validity of a short food frequency questionnaire on present dietary intake of elderly Icelanders. Nutr. J. 2012, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, J.K.; English, D.R.; Fahey, M.T.; Forbes, A.B.; Gurrin, L.C.; Simpson, J.A.; Brinkman, M.T.; Giles, G.G.; Hodge, A.M. Validity and calibration of the FFQ used in the Melbourne collaborative cohort study. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 2357–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presse, N.; Shatenstein, B.; Kergoat, M.J.; Ferland, G. Validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire measuring dietary vitamin K intake in elderly people. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2009, 109, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravia, L.; Gonzalez-Zapata, L.I.; Rendo-Urteaga, T.; Ramos, J.; Collese, T.S.; Bove, I.; Delgado, C.; Tello, F.; Iglesia, I.; Gonçalves Sousa, E.D.; et al. Development of a food frequency questionnaire for assessing dietary intake in children and adolescents in South America. Obesity 2018, 26, S31–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, M.; Yuan, Z.; Lin, L.; Hu, B.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jin, L.; Lu, M.; Ye, W. Reproducibility and relative validity of a food frequency questionnaire developed for adults in Taizhou, China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.F.; Skeaff, S.A. Assessment of population iodine status. In Iodine Deficiency Disorders and Their Elimination; Pearce, E.N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas, R.; Yang, G.; Liu, D.; Xiang, Y.B.; Cai, H.; Zheng, W.; Shu, X.O. Validity and reproducibility of the food-frequency questionnaire used in the Shanghai men’s health study. Br. J. Nutr. 2007, 97, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar, P.C.; Lerma, J.C.; Marin, D.H.; Donat Aliaga, E.; Masip Simó, E.; Polo Miquel, B.; Ribes Koninckx., C. Development and validation of two food frequency questionnaires to assess gluten intake in children up to 36 months of age. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar]

- Vioque, J.; Navarrete-Munoz, E.M.; Gimenez-Monzo, D.; García-de-la-Hera, M.; Granado, F.; Young, I.S.; Ramón, R.; Ballester, F.; Murcia, M.; Rebagliato, M.; Iñiguez, C. INMA-Valencia Cohort Study. Reproducibility and validity of a food frequency questionnaire among pregnant women in a Mediterranean area. Nutr. J. 2013, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Ballart, J.D.; Pinol, J.L.; Zazpe, I.; Corella, D.; Carrasco, P.; Toledo, E.; Perez-Bauer, M.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Martín-Moreno, J.M. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1808–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Moreno, J.M.; Boyle, P.; Gorgojo, L.; Maisonneuve, P.; Fernandez-Rodriguez, J.C.; Salvini, S.; Willett, W.C. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J. Epidemiol. 1993, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyrovolas, S.; Pounis, G.; Bountziouka, V.; Polychronopoulos, E.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Repeatability and validation of a short, semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire designed for older adults living in Mediterranean areas: The MEDIS-FFQ. J. Nutr. Elderly 2010, 29, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.; McLean, R.; Davies, B.; Hawkins, R.; Meiklejohn, E.; Ma, Z.F.; Skeaff, S. Adequate iodine status in New Zealand School children post-fortification of bread with iodised salt. Nutrients 2016, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willet, W. Nutritional Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verdú, J.M. Tabla de Composición de Alimentos, 4nd ed.; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios, C.; Trak, M.A.; Betancourt, J.; Joshipura, K.; Tucker, K.L. Validation and reproducibility of a semi-quantitative FFQ as a measure of dietary intake in adults from Puerto Rico. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2550–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.; Bhatia, V.; Boddula, R.; Singh, H.K.; Bhatia, E. Validation and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire to assess energy and fat intake in affluent north Indians. Natl. Med. J. India. 2005, 18, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bohlscheid-Thomas, S.; Hoting, I.; Boeing, H.; Boeing, H.; Wahrendorf, J. Reproducibility and relative validity of energy and macronutrient intake of a food frequency questionnaire developed for the German part of the EPIC project. European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1997, 26, S71–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschamps, V.; de Lauzon-Guillain, B.; Lafay, L.; Borys, J.M.; Charles, M.A.; Romon, M. Reproducibility and relative validity of a food-frequency questionnaire among French adults and adolescents. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 63, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osowski, J.M.; Beare, T.; Specker, B. Validation of a food frequency questionnaire for assessment of calcium and bone-related nutrient intake in rural populations. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2007, 107, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, M.D.; Motswagole, B.S.; Kwape, L.D.; Kobue-Lekalake, R.I.; Rakgantswana, T.B.; Mongwaketse, T.; Mokotedi, M.; Jackson-Malete, J. Validation and reproducibility of an FFQ for use among adults in Botswana. Public Health Nutr. 2013, 16, 1995–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannelli, J.; Dallongeville, J.; Wagner, A.; Bongard, V.; Laillet, B.; Marecaux, N.; Ruidavets, J.B.; Haas, B.; Ferrieres, J.; et al. Validation of a short, qualitative food frequency questionnaire in French adults participating in the MONA LISA-NUT study 2005–2007. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet 2014, 114, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakseresht, M.; Sharma, S. Validation of a quantitative food frequency questionnaire for Inuit population in Nunavut, Canada. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 2010, 23, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Yan, H.; Dibley, M.J.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zeng, L. Validity and reproducibility of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire for use among pregnant women in rural China. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 17, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Song, S.; Lee, J.E.; Oh, K.; Shim, J.; Kweon, S.; Paik, H.Y.; Joung, H. Reproducibility and validity of an FFQ developed for the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (N = 341) | Women (N = 191) | Men (N = 150) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Age | |||

| Mean | 72.59 | 73.38 | 71.58 |

| SD | 8.29 | 8.16 | 8.38 |

| Weight | |||

| Mean (kg) | 74.68 | 70.25 | 80.32 |

| SD | 12.89 | 11.67 | 12.18 |

| BMI | |||

| Mean | 27.61 | 27.69 | 27.52 |

| SD | 6.72 | 4.69 | 4.79 |

| Years of education | |||

| None | 43 (12.60) | 30 (15.70) | 13 (8.70) |

| 1–5 years | 66 (19.51) | 38 (19.90) | 28 (18.70) |

| 5–10 years | 123 (36.12) | 68 (35.60) | 55 (36.70) |

| >10 years | 109 (32.00) | 55 (28.80) | 54 (36.00) |

| Place of Residence | |||

| Urban | 271 (79.47) | 150 (78.50) | 121 (80.70) |

| Rural | 70 (20.53) | 41 (21.50) | 29 (19.30) |

| Civil Status | |||

| Married | 218 (63.93) | 114 (59.70) | 104 (69.30) |

| Widowed | 89 (26.10) | 60 (31.43) | 29 (19.30) |

| Divorced | 12 (3.52) | 7 (3.70) | 5 (3.30) |

| Single | 10 (2.93) | 6 (3.10) | 4 (2.70) |

| Living as a couple | 12 (3.52) | 4 (2.10) | 8 (5.30) |

| Alcohol Consumption | |||

| No | 150 (43.79) | 106 (55.50) | 44 (29.30) |

| Yes, usually | 32 (9.38) | 5 (2.60) | 27 (18.00) |

| Yes, occasional | 159 (46.63) | 80 (41.90) | 79 (52.70) |

| Tobacco Consumption | |||

| No | 257 (75.37) | 156 (81.68) | 104 (69.30) |

| Yes, usually | 65 (19.06) | 30 (15.70) | 35 (23.30) |

| Yes, occasional | 16 (4.69) | 5 (2.60) | 11 (7.30) |

| Physical Activity | |||

| No | 92 (26.98) | 56 (29.30) | 36 (24.00) |

| <2.5 h/week | 66 (19.35) | 42 (22.00) | 24 (16.00) |

| 2.5–7 h/week | 126 (36.95) | 74 (38.70) | 52 (34.70) |

| >7 h/week | 57 (16.74) | 19 (9.90) | 38 (25.30) |

| Food Groups | FFQ 1 | FFQ 2 | 24-HDR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Dairy products (g) | 377.87 | 233.87 | 344.08 | 218.33 | 356.89 | 200.33 |

| Starchy foods (g) | 213.02 | 141.67 | 212.67 | 77.30 | 200.89 | 89.76 |

| Meat (g) | 140.04 | 87.42 | 140.89 | 75.28 | 145.98 | 77.89 |

| Fish (g) | 98.99 | 75.39 | 99.71 | 74.56 | 97.76 | 70.54 |

| Legumes (g) | 70.52 | 50.53 | 69.68 | 49.87 | 72.34 | 45.67 |

| Vegetables (g) | 205.45 | 122.84 | 207.65 | 123.45 | 201.76 | 121.98 |

| Fruits (g) | 475.06 | 212.4 | 469.98 | 201.50 | 450.98 | 200.7 |

| Nuts (g) | 8.21 | 4.67 | 8.09 | 4.53 | 7.98 | 4.56 |

| Sweets (g) | 95.52 | 34.56 | 90.92 | 30.12 | 93.45 | 30.21 |

| Snacks (g) | 30.48 | 22.24 | 35.29 | 25.86 | 32.12 | 21.34 |

| EVOO (g) | 62.32 | 38.36 | 61.97 | 37.32 | 60.78 | 35.45 |

| Alcoholic beverages (g) | 98.47 | 23.34 | 103.85 | 24.67 | 100.34 | 22.34 |

| Nutrient | FFQ 1 | FFQ 2 | 24-HDR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Energy (kcal) | 2222.49 | 455.80 | 2380.08 | 1685.59 | 2301.28 | 920.15 |

| Proteins (g) | 88.52 | 58.66 | 87.58 | 39.29 | 88.05 | 37.44 |

| Lipids (g) | 96.48 | 23.03 | 99.16 | 54.20 | 97.82 | 33.72 |

| Saturated fats (g) | 28.97 | 5.69 | 29.04 | 5.78 | 29.00 | 5.70 |

| MUFAs (g) | 42.08 | 12.22 | 40.68 | 9.99 | 41.38 | 10.23 |

| PUFAs (g) | 13.84 | 3.94 | 13.92 | 4.07 | 13.88 | 3.96 |

| Cholesterol (g) | 242.50 | 69.56 | 240.13 | 67.25 | 241.32 | 66.63 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 283.99 | 54.23 | 284.24 | 54.72 | 284.12 | 54.46 |

| Fibre (g) | 31.15 | 9.35 | 31.52 | 10.14 | 31.33 | 9.43 |

| Potassium (mg) | 3545.14 | 721.29 | 3670.94 | 2518.52 | 3608.04 | 1432.14 |

| Sodium (mg) | 2677.46 | 670.22 | 2687.47 | 674.38 | 2682.47 | 668.83 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1198.45 | 525.36 | 1175.82 | 313.76 | 1187.14 | 371.66 |

| Iron (mg) | 12.16 | 3.27 | 12.54 | 8.41 | 12.35 | 5.13 |

| Iodide (μg) | 105.69 | 58.50 | 106.53 | 70.30 | 106.06 | 51.67 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 1.57 | 1.03 | 1.53 | 0.90 | 1.55 | 0.73 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 3.03 | 1.58 | 2.98 | 1.16 | 3.00 | 1.27 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 2.51 | 0.85 | 2.50 | 0.85 | 2.51 | 0.84 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 11.66 | 5.34 | 11.70 | 5.57 | 11.68 | 5.34 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 255.63 | 102.32 | 255.72 | 103.77 | 255.68 | 101.92 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 1180.73 | 890.26 | 1140.96 | 859.57 | 1160.84 | 657.02 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 5.77 | 2.78 | 5.78 | 2.83 | 5.78 | 2.79 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 16.09 | 6.66 | 16.25 | 6.60 | 16.17 | 6.49 |

| Nutrient | Interclass Correlation Coefficient | Agreement (%) * | Agreement Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted † | |||

| Energy (kcal) | 0.99 | - | 55.5 | <0.01 |

| Proteins (g) | 0.88 | 0.79 | 30.7 | <0.01 |

| Lipids (g) | 0.86 | 0.85 | 40.1 | <0.01 |

| Saturated fats (g) | 0.99 | 0.81 | 99.6 | <0.01 |

| MUFAs (g) | 0.81 | 0.80 | 77.8 | <0.01 |

| PUFAs (g) | 0.97 | 0.79 | 89.4 | <0.01 |

| Cholesterol (g) | 0.89 | 0.80 | 42.7 | <0.01 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 0.99 | 0.86 | 88.7 | <0.01 |

| Fibre (g) | 0.87 | 0.78 | 71.7 | <0.01 |

| Potassium (mg) | 0.33 | 0.30 | 87.6 | <0.01 |

| Sodium (mg) | 0.99 | 0.89 | 40.1 | <0.01 |

| Calcium (mg) | 0.66 | 0.64 | 78.9 | <0.01 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.45 | 0.44 | 56.7 | <0.01 |

| Iodide (μg) | 0.43 | 0.45 | 54.7 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.57 | 0.56 | 67.8 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.80 | 0.81 | 67.8 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.98 | 0.87 | 98.7 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 0.96 | 0.90 | 90.7 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0.96 | 0.89 | 78.9 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 0.50 | 0.49 | 55.6 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 0.98 | 0.91 | 87.6 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 0.98 | 0.87 | 89.8 | <0.01 |

| Nutrient | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient | Difference of Means | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted * | Mean | SD | |

| Energy (kcal) | 0.97 | - | 1.97 | 31.07 |

| Proteins (g) | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.26 | 2.01 |

| Lipids (g) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 1.34 | 24.43 |

| Saturated fats (g) | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| MUFAs (g) | 0.90 | 0.90 | −0.70 | 4.46 |

| PUFAs (g) | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.61 |

| Cholesterol (g) | 0.97 | 0.97 | −1.18 | 15.52 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.12 | 1.58 |

| Fibre (g) | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.19 | 2.50 |

| Potassium (mg) | 0.97 | 0.97 | 62.90 | 1174.99 |

| Sodium (mg) | 0.89 | 0.99 | 5.00 | 68.27 |

| Calcium (mg) | 0.80 | 0.80 | −11.32 | 221.58 |

| Iron (mg) | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.19 | 3.80 |

| Iodide (μg) | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 38.89 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.71 | 0.71 | −0.20 | 0.64 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.89 | 0.89 | −0.22 | 0.56 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.99 | 0.99 | −0.01 | 0.11 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.2 | 1.11 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 15.22 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 0.74 | 0.78 | −19.89 | 577.95 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 0.88 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 0.32 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.08 | 1.36 |

| Nutrient | FFQ2 vs. 24-HDR | Kappa | Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Same (%) | Adjacent (%) | Extreme (%) | |||

| Energy (kcal) | 95.88 | 4.12 | 0.00 | 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Proteins (g) | 97.94 | 2.06 | 0.00 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Lipids (g) | 94.12 | 5.88 | 0.00 | 0.92 | <0.01 |

| Saturated fats (g) | 95.29 | 4.71 | 0.00 | 0.94 | <0.01 |

| MUFAs (g) | 90.88 | 7.35 | 0.59 | 0.88 | <0.01 |

| PUFAs (g) | 98.53 | 1.47 | 0.59 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

| Cholesterol (g) | 96.18 | 2.94 | 0.29 | 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 95.29 | 2.94 | 0.59 | 0.94 | <0.01 |

| Fibre (g) | 97.65 | 2.35 | 0.00 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Potassium (mg) | 98.53 | 1.47 | 0.00 | 0.98 | <0.01 |

| Sodium (mg) | 99.88 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Calcium (mg) | 97.65 | 1.76 | 0.29 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Iron (mg) | 96.18 | 3.53 | 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Iodide (μg) | 97.35 | 2.05 | 0.00 | 0.96 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 83.53 | 14.12 | 2.06 | 0.78 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 97.65 | 4.71 | 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 89.44 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 0.86 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg) | 95.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 95.29 | 4.41 | 0.00 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin A (μg) | 83.53 | 15.59 | 0.59 | 0.78 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin D (μg) | 92.35 | 7.64 | 0.00 | 0.89 | <0.01 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 87.65 | 12.03 | 0.29 | 0.84 | <0.01 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaragoza-Martí, A.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Hurtado-Sánchez, J.A.; Laguna-Pérez, A.; Cabañero-Martínez, M.J. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reproducibility of the Mediterranean Islands Study Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Elderly Population Living in the Spanish Mediterranean. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091206

Zaragoza-Martí A, Ferrer-Cascales R, Hurtado-Sánchez JA, Laguna-Pérez A, Cabañero-Martínez MJ. Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reproducibility of the Mediterranean Islands Study Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Elderly Population Living in the Spanish Mediterranean. Nutrients. 2018; 10(9):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091206

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaragoza-Martí, Ana, Rosario Ferrer-Cascales, José Antonio Hurtado-Sánchez, Ana Laguna-Pérez, and María José Cabañero-Martínez. 2018. "Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reproducibility of the Mediterranean Islands Study Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Elderly Population Living in the Spanish Mediterranean" Nutrients 10, no. 9: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091206

APA StyleZaragoza-Martí, A., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Hurtado-Sánchez, J. A., Laguna-Pérez, A., & Cabañero-Martínez, M. J. (2018). Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Validity, and Reproducibility of the Mediterranean Islands Study Food Frequency Questionnaire in the Elderly Population Living in the Spanish Mediterranean. Nutrients, 10(9), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091206