Clinical Management of Low Vitamin D: A Scoping Review of Physicians’ Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

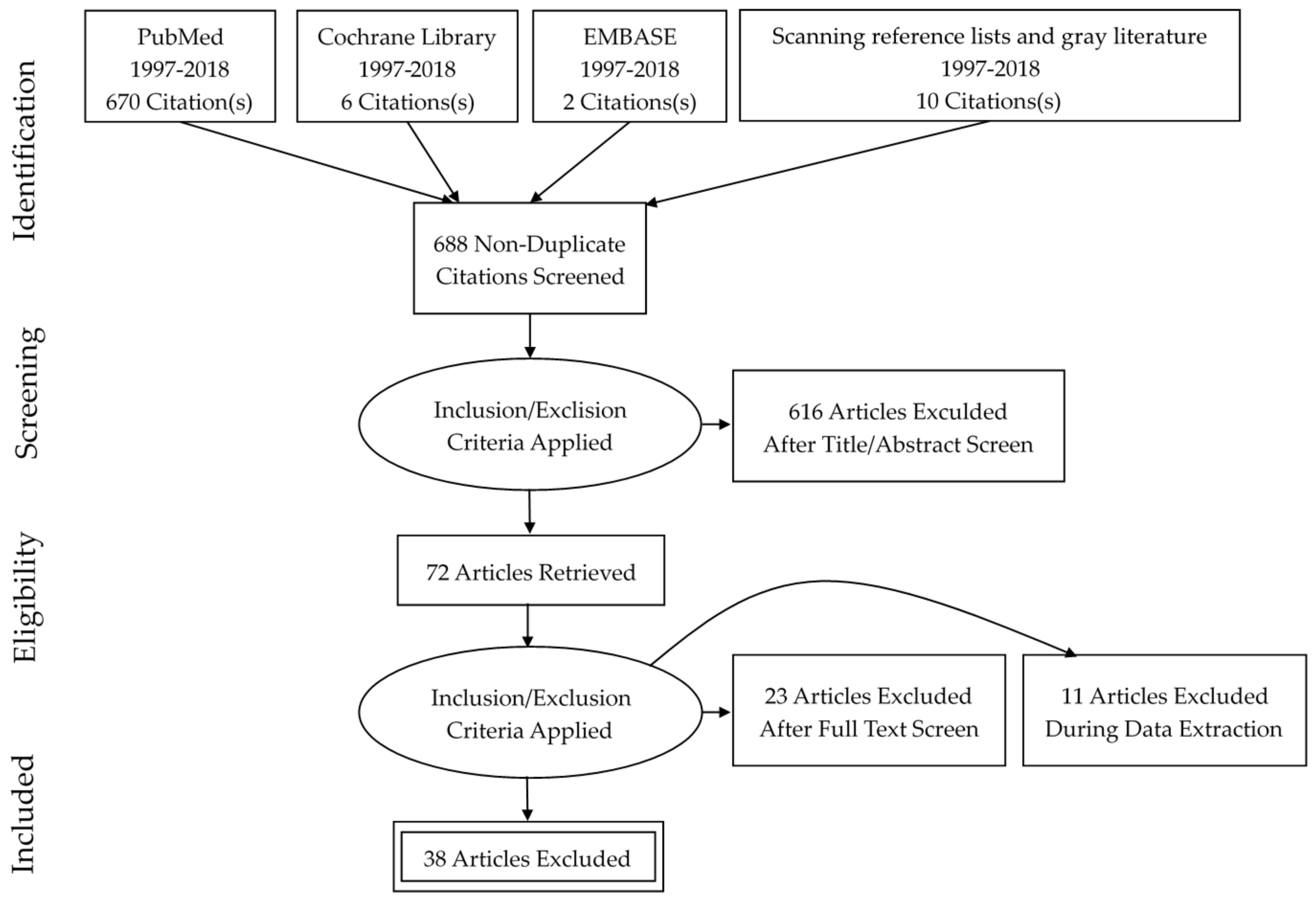

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Vitamin D Laboratory Testing

3.2. Vitamin D Prescriptions

3.3. Physicians’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors Related to Management of LVD

3.3.1. Physicians’ Knowledge

3.3.2. Communication

3.3.3. Testing and Treatment

3.3.4. Attitudes

3.4. Economic Impact

3.5. Efforts to Constrain Inappropriate Clinical Practice Related to Low Vitamin D

4. Discussion

4.1. Future Research

4.2 Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennel, K.A.; Drake, M.T.; Hurley, D.L. Vitamin D deficiency in adults: When to test and how to treat. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2010, 85, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holick, M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017, 18, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manson, J.E.; Brannon, P.M.; Rosen, C.J.; Taylor, C.L. Vitamin D deficiency-is there really a pandemic? N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 1817–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.W. Vitamin D screening and supplementation in primary care: Time to curb our enthusiasm. Am. Fam. Phys. 2018, 97, 226–227. [Google Scholar]

- Veith, R. Vitamin D supplementation, 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, and safety. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holick, M.F.; Binkley, N.C.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Gordon, C.M.; Hanley, D.A.; Heaney, R.P.; Murad, M.H.; Weaver, C.M. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Academy of Family Physicians. Clinical Preventive Service Recommendation: Vitamin D Deficiency (2014). Available online: https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/vitamin-D-deficiency.html (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Canadian Medical Association. Guideline for Vitamin D Testing and Supplementation in Adults (2012). Available online: https://www.cma.ca/En/Pages/cpg-by-condition.aspx?conditionCode=81 (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Pludowski, P.; Karczmarewicz, E.; Bayer, M.; Carter, G.; Chlebna-Sokol, D.; Czech-Kowalska, J.; Dębski, R.; Decsi, T.; Dobrzańska, A.; Franek, E.; et al. Practical guidelines for the supplementation of vitamin D and the treatment of deficits in Central Europe-recommended vitamin D intakes in the general population and groups at risk of vitamin D deficiency. Endokrynol. Pol. 2013, 64, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketteler, M.; Block, G.A.; Evenepoel, P.; Fukagawa, M.; Herzog, C.A.; McCann, L.; Moe, S.M.; Shroff, R.; Tonelli, M.A.; Toussaint, N.D.; et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease—Mineral and bone disorder: Synopsis of the kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 168, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeFevre, M.L. Screening for vitamin d deficiency in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Int. Med. 2015, 162, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian and New Zealand Bone Mineral Society/Endocrine Society of Australia and Osteoporosis Australia. Vitamin D and health in adults in Australia and New Zealand: A position statement. Med. J. Aust. 2012, 196, 686–687. [Google Scholar]

- The National Osteoporosis Society. Vitamin D and Bone Health: A Practical Clinical Guideline for Patient Management (2017). Available online: https://nos.org.uk/media/2073/vitamin-d-and-bone-health-adults (accessed on 15 November 2017).

- Vemulapati, S.; Rey, E.; O’Dell, D.; Mehta, S.; Erickson, D. A quantitative point-of-need assay for the assessment of vitamin D3 deficiency. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spedding, S. Vitamin D and human health. Nutrients 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.L.; Ernst, J.Z. Controversies in vitamin D recommendations and its possible roles in non-skeletal health issues. Nutr. Food Sci. 2013, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejnmark, L.; Bislev, L.S.; Cashman, K.D.; Eiriksdottir, G.; Gaksch, M.; Grubler, M.; Grimnes, G.; Gudnason, V.; Lips, P.; Pilz, S.; et al. Non-skeletal health effects of vitamin D supplementation: A systematic review on findings from meta-analyses summarizing trial data. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0180512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeFevre, M.L.; LeFebre, N.M. Vitamin D screening and supplementation in community-dwelling adults: Common questions and answers. Am. Fam. Phys. 2018, 97, 254–260. [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield, T.; Clark, M.I.; McCormack, J.P.; Rachul, C.; Field, C.J. Representations of the health value of vitamin D supplementation in newspapers: Media content analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 12, e006395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotta, S.; Gadhvi, D.; Jakeways, N.; Saeed, M.; Sohanpal, R.; Hull, S.; Famakin, O.; Martineau, A.; Griffiths, C. “Test me and treat me”—Attitudes to vitamin D deficiency and supplementation: A qualitative study. Br. Med. J. 2015, 5, e007401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.M. Pathology consultation on vitamin D testing: Clinical indications for 25(OH) vitamin D measurement. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 137, 831–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, M.; Ding, E.L.; Theisen-Toupal, J.; Whelan, J.; Arnaout, R. The landscape of inappropriate laboratory testing: A 15-year meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, G. The laboratory test utilization management toolbox. Biochem. Med. 2014, 24, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, D.; Santa, J.; Slass, L. Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: A short history of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2014, 89, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colla, C.H.; Morden, N.E.; Sequist, T.D.; Schpero, W.L.; Rosenthal, M.B. Choosing wisely: Prevalence and correlates of low-value health care services in the united states. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2015, 30, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.; Hall, B.J.; Doyle, J.; Waters, E. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a Cochrane Review. J. Public Health 2011, 33, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Int. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilinski, K.; Boyages, S. Evidence of overtesting for vitamin D in Australia: An analysis of 4.5 years of Medicare benefits schedule (MBS) data. Br. Med. J. 2013, 3, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahangian, S.; Alspach, T.D.; Astles, J.R.; Yesupriya, A.; Dettwyler, W.K. Trends in laboratory test volumes for Medicare part B reimbursements, 2000–2010. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2014, 138, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Gardner, K.; Taylor, W.; Marks, E.; Goodson, N. Vitamin D assessment in primary care: Changing patterns of testing. Lond. J. Prim. Care 2015, 7, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillet, P.; Goyer-Joos, A.; Viprey, M.; Schott, A.M. Increase of vitamin D assays prescriptions and associated factors: A population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattar, N.; Welsh, P.; Panarelli, M.; Forouhi, N.G. Increasing requests for vitamin D measurement: Costly, confusing, and without credibility. Lancet 2012, 379, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinski, K.; Boyages, S. The vitamin D paradox: Bone density testing in females aged 45 to 74 did not increase over a ten-year period despite a marked increase in testing for vitamin D. J. Endocr. Investig. 2013, 36, 914–922. [Google Scholar]

- Colla, C.; Morden, N.; Sequist, T.; Mainor, A.; Li, Z.; Rosenthal, M. Payer type and low-value care: comparing Choosing Wisely services across commercial and Medicare populations. Health Serv. Res. 2017, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Koning, L.; Henne, D.; Woods, P.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Naugler, C. Sociodemographic correlates of 25-hydroxyvitamin D test utilization in Calgary, Alberta. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, U.; Smith, B.J.; Wluka, A.E.; Fong, D.P.; Kaur, A.; Renzaho, A.M. Vitamin D testing patterns among general practitioners in a major Victorian primary health care service. Aust. N. Zeal. J. Public Health 2016, 40, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalifa, M.; Zabani, I.; Khalid, P. Exploring lab tests over utilization patterns using health analytics methods. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 226, 190–193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tapley, A.; Magin, P.; Morgan, S.; Henderson, K.; Scott, J.; Thomson, A.; Spike, N.; McArthur, L.; van Driel, M.; McElduff, P.; et al. Test ordering in an evidence free zone: Rates and associations of Australian general practice trainees’ vitamin D test ordering. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, M.; Yu, R.; Deutsch, S.C. Insignificant medium-term vitamin D status change after 25-hydroxyvitamin D testing in a large managed care population. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Norton, K.; Vasikaran, S.D.; Chew, G.T.; Glendenning, P. Is vitamin D testing at a tertiary referral hospital consistent with guideline recommendations? Pathology 2015, 47, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, B.A.; Manning, T.; Peiris, A.N. Vitamin D testing patterns among six Veteran’s Medical Centers in the southeastern United States: Links with medical costs. Mil. Med. 2012, 177, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairfield, K. Low value vitamin D screening in northern New England. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Lown Institute Conference-Research Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 5–7 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caillet, P.; Souberbielle, J.C.; Jaglal, S.B.; Reymondier, A.; Van Ganse, E.; Chapurlat, R.; Schott, A.M. Vitamin D supplementation in a healthy, middle-aged population: Actual practices based on data from a French comprehensive regional health-care database. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 1133–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartels, M. Most People Don’t Need to Be Tested for Vitamin D Deficiency; Excellus BlueCross BlueShield: Rochester, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.E.; Milliron, B.J.; Davis, S.A.; Feldman, S.R. Surge in US outpatient vitamin D deficiency diagnoses: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey analysis. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzoni, M.; Fornili, M.; Felicetta, I.; Maiavacca, R.; Biganzoli, E.; Castaldi, S. Three-year analysis of repeated laboratory tests for the markers total cholesterol, ferritin, vitamin D, vitamin B12, and folate, in a large research and teaching hospital in Italy. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianferotti, L.; Parri, S.; Gronchi, G.; Rizzuti, C.; Fossi, C.; Black, D.M.; Brandi, M.L. Changing patterns of prescription in vitamin D supplementation in adults: Analysis of a regional dataset. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 2695–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratton-Loeffler, M.J.; Lo, J.C.; Hui, R.L.; Coates, A.; Minkoff, J.R.; Budayr, A. Treatment of vitamin D deficiency within a large integrated health care delivery system. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2012, 18, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepper, K.J.; Judd, S.E.; Nanes, M.S.; Tangpricha, V. Evaluation of vitamin D repletion regimens to correct vitamin D status in adults. Endocr. Pract. 2009, 15, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeder, A.I.; Jopson, J.A.; Gray, A.R. “Prescribing sunshine”: A national, cross-sectional survey of 1,089 New Zealand general practitioners regarding their sun exposure and vitamin D perceptions, and advice provided to patients. BMC Fam. Pract. 2012, 13, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonevski, B.; Girgis, A.; Magin, P.; Horton, G.; Brozek, I.; Armstrong, B. Prescribing sunshine: A cross-sectional survey of 500 Australian general practitioners’ practices and attitudes about vitamin D. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 2138–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, A.; Al-Amri, F.; Al-Habib, D.; Gad, A. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding vitamin D among primary health care physicians in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia, 2015. World J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 1, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Epling, J.W.; Mader, E.M.; Roseamelia, C.A.; Morley, C.P. Emerging practice concerning vitamin D in primary care. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarn, D.M.; Paterniti, D.A.; Wenger, N.S. Provider recommendations in the face of scientific uncertainty: An analysis of audio-recorded discussions about vitamin D. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2016, 31, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, K.; Frisby, B.N.; Young, L.E.; Murray, D. Vitamin D: An examination of physician and patient management of health and uncertainty. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilinski, K.; Boyages, S. The rise and rise of vitamin D testing. BMJ Online 2012, 345, e4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mafi, J.N.; Russell, K.; Bortz, B.A.; Dachary, M.; Hazel, W.A., Jr.; Fendrick, A.M. Low-cost, high-volume health services contribute the most to unnecessary health spending. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1701–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Care Expenditures by State of Provider. The Kaiser Family Foundation: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.kff.org/health-costs/ (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Peiris, A.N.; Bailey, B.A.; Manning, T. The relationship of vitamin D deficiency to health care costs in veterans. Mil. Med. 2008, 173, 1214–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannemann, A.; Wallaschofski, H.; Nauck, M.; Marschall, P.; Flessa, S.; Grabe, H.J.; Schmidt, C.O.; Baumeister, S.E. Vitamin D and health care costs: Results from two independent population-based cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souberbielle, J.C.; Benhamou, C.L.; Cortet, B.; Rousiere, M.; Roux, C.; Abitbol, V.; Annweiler, C.; Audran, M.; Bacchetta, J.; Bataille, P.; et al. French law: What about a reasoned reimbursement of serum vitamin D assays? Geriatrie. et Psychologie Neuropsychiatrie du Vieillissement 2016, 14, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Changing OHIP Coverage for Vitamin D Testing. Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. Available online: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/news/bulletin/2010/20101130.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2017).

- Deschasaux, M.; Souberbielle, J.C.; Andreeva, V.A.; Sutton, A.; Charnaux, N.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Latino-Martel, P.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Szabo de Edelenyi, F.; Galan, P.; et al. Quick and easy screening for vitamin D insufficiency in adults: A scoring system to be implemented in daily clinical practice. Medicine 2016, 95, e2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, H.; Straseski, J.A.; Genzen, J.R.; Walker, B.S.; Jackson, B.R.; Schmidt, R.L. Benchmarking to identify practice variation in test ordering: A potential tool for utilization management. Lab. Med. 2015, 46, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felcher, A.H.; Gold, R.; Mosen, D.M.; Stoneburner, A.B. Decrease in unnecessary vitamin D testing using clinical decision support tools: Making it harder to do the wrong thing. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2017, 24, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.A.; McKinney, C.M.; Hoffman, N.G.; Sutton, P.R. Optimizing vitamin D naming conventions in computerized order entry to support high-value care. J. Am. Med. Informat. Assoc. 2017, 24, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelloso, M.; Basso, D.; Padoan, A.; Fogar, P.; Plebani, M. Computer-based-limited and personalised education management maximize appropriateness of vitamin D, vitamin B12 and folate retesting. J. Clin. Pathol. 2016, 69, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, E.; Song, S.; Al-Abboud, O.; Shams, S.; English, J.; Naji, W.; Huang, Y.; Robison, L.; Balis, F.; Kawsar, H.I. An educational intervention to increase awareness reduces unnecessary laboratory testing in an internal medicine resident-run clinic. J. Community Hosp. Int. Med. Pers. 2017, 7, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, K.; Zhao, S. Vitamin D testing: Three important issues. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 64, 124–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mittelstaedt, M. Ontario Nixes Funding for Vitamin D Tests 2017. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/health-and-fitness/ontario-nixes-funding-for-vitamin-d-tests/article1315515/ (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Smellie, S.A. Demand management and test request rationalization. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 49, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabbay, J.; Le May, A. Evidence based guidelines or collectively constructed “mindlines?” Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care. Br. Med. J. 2004, 329, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peckham, C. Physician Compensation Report: 2016. Available online: http://www.medscape. com/features/slideshow/compensation/2016/public/overview (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Chen, P. Why Doctors Order So Many Tests; The New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Recommendation | Population-Wide 25-OH-D Screening Recommended? | 25-OH-D Testing for Individuals at High Risk of Deficiency Recommended? | Definition of “High Risk” |

|---|---|---|---|

| American Academy of Family Physicians [8] | Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for vitamin D deficiency (I) | No | N/A |

| Canadian Medical Association [9] | No | Yes | Significant renal or liver disease Osteomalacia, osteopenia or osteoporosis Malabsorption syndromes Hypo or hypercalcemia/ hyperphosphatemia Hypo or hyperparathyroidism Patients on medications that affect vitamin D metabolism or absorption Unexplained increased levels of serum alkaline phosphatase Patients taking high doses of vitamin D (>2000 IU daily) for extended periods of time (>6 months), and who are exhibiting symptoms suggestive of vitamin D toxicosis (hypervitaminosis D) |

| Central European Scientific Committee on Vitamin D [10] | No | Yes | Rickets, osteomalacia, osteoporosis, musculoskeletal pain, history of fracture or falls Calcium/phosphate metabolism abnormalities Hyperparathyroidism Malabsorption syndromes At-risk medications Dietary restriction, parenteral nutrition, eating disorder Kidney disease (stages 3–5) or transplant, liver disease, autoimmune disease, cardiovascular disease, some cancers, some infections |

| Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) [11] | No | Yes | Stage 3–5 kidney disease, particularly if on dialysis |

| U.S. Endocrine Society [7] | No | Yes | Rickets, osteomalacia, osteoporosis Chronic kidney disease Hepatic failure Malabsorption syndromes Certain medications African-American and Hispanic children and adults Pregnant and lactating women Older adults with history of falls or non-traumatic fractures Obese children and adults Granuloma-forming disorders Some lymphomas |

| U.S. Preventive Services Task Force [12] | Current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening in asymptomatic adults (I statement) | N/A | N/A |

| Recommendation | Vitamin D Deficiency (25-OH-D) | Vitamin D Insufficiency (25-OH-D) | Adequate Vitamin D (25-OH-D) | Toxicity (25-OH-D) |

| Australian and New Zealand Bone Mineral Society/Endocrine Society of Australia and Osteoporosis Australia [13] | Mild deficiency: 12–19.5 ng/mL Moderate deficiency: 5–12 ng/mL Severe deficiency: <5 ng/mL | 20 ng/mL at the end of winter; 24–28 ng/mL at the end of summer to allow for seasonal decrease | Not defined | |

| Central European Scientific Committee on Vitamin D [10] | <20 ng/mL | 20–30 ng/mL | 30–50 ng/mL | >100 ng/mL |

| National Academy of Medicine (formerly IOM) [6] | <12.5 ng/mL | Not defined | 12–20 ng/mL 25-OH-D of 20 ng/mL is sufficient to meet needs of 97.5% of the population | >50 ng/mL |

| Public Health England/National Osteoporosis Society [14] | <10 ng/mL | 10–19.5 ng/mL | >20 ng/mL | Not defined |

| U.S. Endocrine Society [7] | <20 ng/mL | 20–30 ng/mL | >30 ng/mL | >150 ng/mL |

| Study | Population | Setting | Time Frame | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilinski and Boyages, 2013 [30] | 2.4 million patients who received 25-OH-D tests (national health system data) | Australia | 4-year period 2006–2010 | 94-fold increase in tests |

| Bilinski and Boyages, 2018 [35] | Women, ages 45–74 (national health system data) | Australia | 10-year period 2001–2011 | 44% increase in tests |

| Caillet et al., 2017 [33] | 639,163 patients (national health insurance database) | France | 1-year period 2008–2009 | 18.5% were tested |

| Colla et al., 2017 [36] | Medicare and commercially insured patients (Health Care Cost Institute database) | United States | 2-year period 2009–2011 | 10–16% of Medicare patents and 5–10% of commercially insured were tested |

| de Koning et al., 2014 [37] | Adult residents of 1436 census regions | Alberta, Canada | 1-year period 2010–2011 | 8% were tested |

| Gowda et al., 2016 [38] | 2187 patients seen in community health center | Melbourne, Australia | 2-year period 2010–2012 | 56% of patients were tested |

| Khalifa et al., 2016 [39] | Hospital patients (King Faisal Hospital and Research Center) | Jeddah, Saudi Arabia | 1-year period 2014–2015 | 30% increase in tests |

| Tapley et al., 2015 [40] | General practice patients (Recent cohort study) | 4 states in Australia | 3-year period 2010–2013 | 1% of patients were tested |

| Wei et al., 2014 [41] | 22,784 managed care patients | California, United States | 2-year period 2011–2013 | 11% of patients were tested |

| Zhao et al., 2015 [32] | Primary care patients | Liverpool, United Kingdom | 5-year period 2007–2012 | 11-fold increase in tests |

| Study/Report | Population | Setting | Timeframe | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartells, 2014 [47] | Commercially insured adult patients | Upstate New York, U.S. | 1-year period 2014 | $33 million spent on 25-OH-D tests |

| Bilinski and Boyages, 2013 [30] | Adults (national health system data) | Australia | 4-year period 2006–2010 | $20 million (Aus.)/$16 million (U.S.) spent on “non-indicated” 25-OH-D tests |

| Bilinski and Boyages, 2013 [35] | Women, ages 45–74 (national health system data) | Australia | 10-year period 2001–2011 | $7 million (Aus.)/$555,492 (U.S.) spent on 25-OH-D tests in 2001 and $40.5 million (Aus.)/$32 million (U.S.) in 2011 |

| Caillet et al., 2016 [33] | All individuals (national health insurance database) | France | 2-year period 2009–2011 | €27 million/$33 million (U.S.) in 2009 to €65 million/$79 million (U.S.) on 25-OH-D tests |

| Cianferotti et al., 2015 [49] | Adults (20–90) | Tuscany, Italy | 7-year period 2006–2013 | €3.2 million/$3.9 million (U.S.) in 2006 to €8.2 million/$10.1 million (U.S.) in 2013 on 25-OH-D tests |

| Colla et al. 2015 [26] | Medicare patients (>65 years of age, qualify based on disability) | U.S. | 5-year period 2006–2011 | $224 million in 2011, average of $198 million/year 2006–2001 on 25-OH-D tests |

| Fairfield, 2017 [44] | All individuals without high risk diagnosis (ex: osteoporosis, malabsorption, liver disease, etc.) | Maine, U.S. | 2-year period 2012–2014 | $9,596,000 spent on “non-indicated” on 25-OH-D tests |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rockwell, M.; Kraak, V.; Hulver, M.; Epling, J. Clinical Management of Low Vitamin D: A Scoping Review of Physicians’ Practices. Nutrients 2018, 10, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040493

Rockwell M, Kraak V, Hulver M, Epling J. Clinical Management of Low Vitamin D: A Scoping Review of Physicians’ Practices. Nutrients. 2018; 10(4):493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040493

Chicago/Turabian StyleRockwell, Michelle, Vivica Kraak, Matthew Hulver, and John Epling. 2018. "Clinical Management of Low Vitamin D: A Scoping Review of Physicians’ Practices" Nutrients 10, no. 4: 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040493

APA StyleRockwell, M., Kraak, V., Hulver, M., & Epling, J. (2018). Clinical Management of Low Vitamin D: A Scoping Review of Physicians’ Practices. Nutrients, 10(4), 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040493