Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Spartina alterniflora–Phragmites australis Mixed Ecotone in Chongming Dongtan Wetland Using an Integrated Three-Dimensional Feature Space and Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation

Highlights

- An integrated method combining a three-dimensional feature space with multi-threshold Otsu segmentation and season-specific indices (NIR/NDVI) enabled high-precision extraction of the invasive–native mixed ecotone, achieving 87.3% overall accuracy.

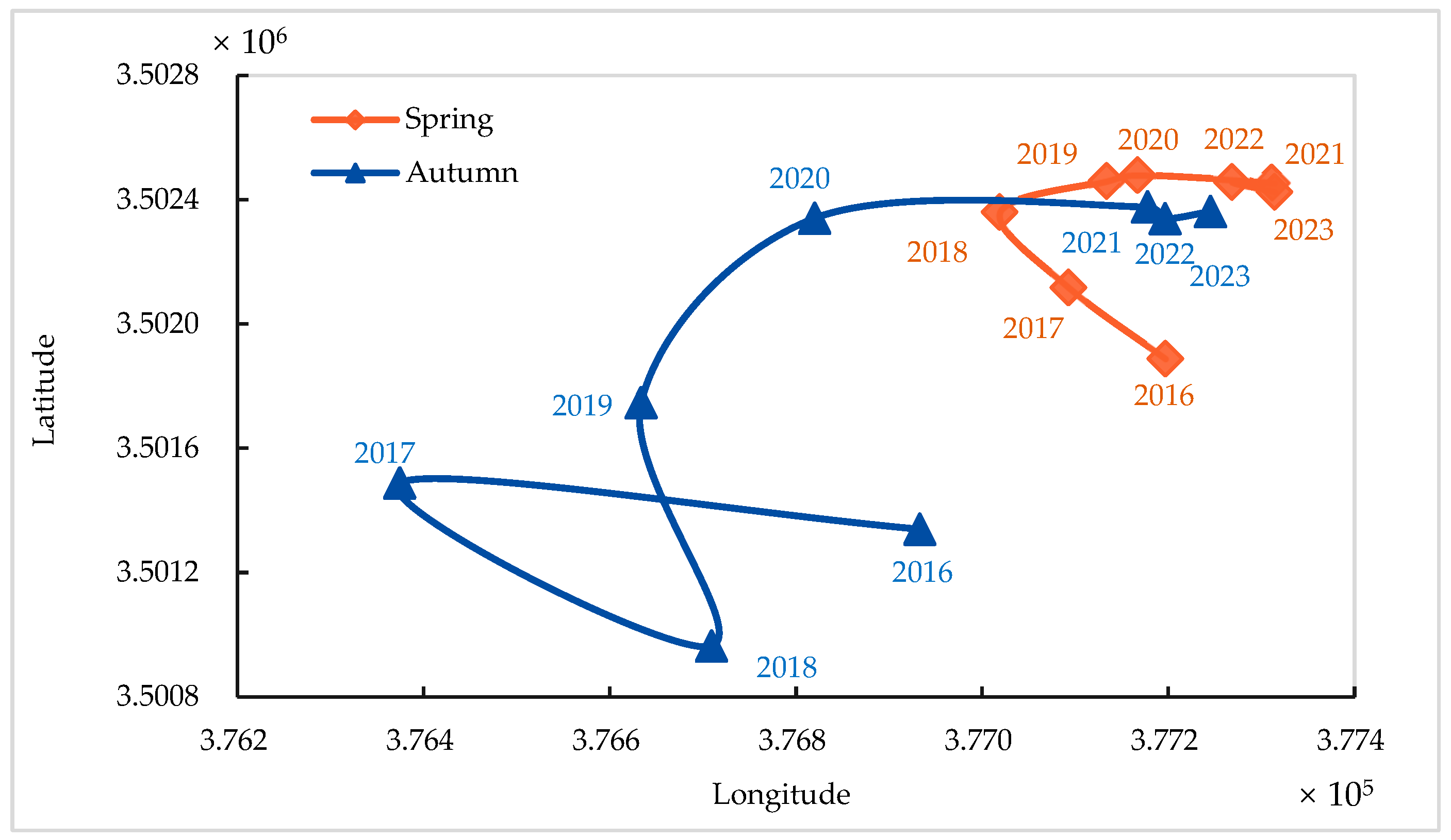

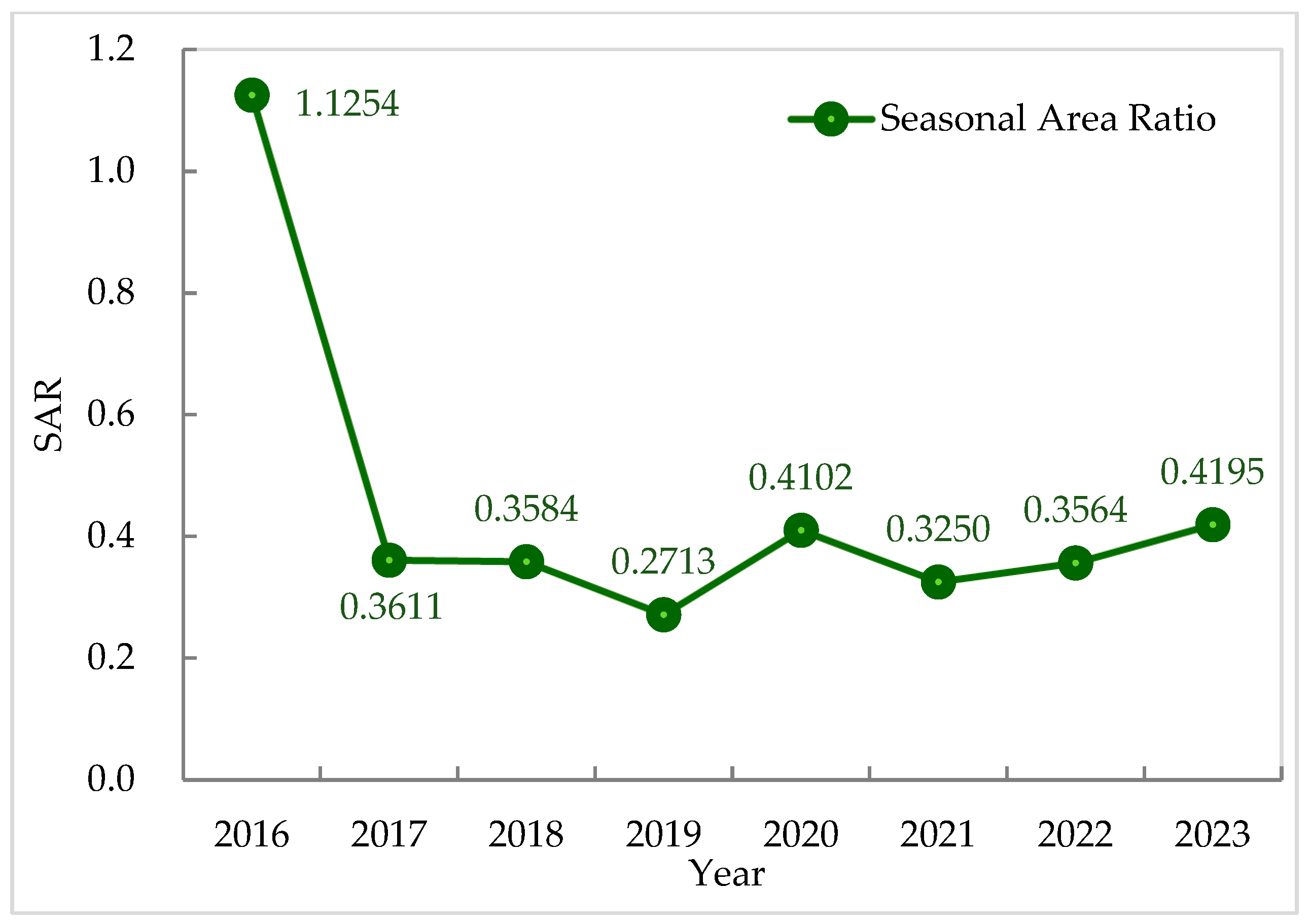

- The mixed ecotone displayed a distinct seaward expansion trend and a composite pattern of regime shift with internal fluctuations, as revealed by the centroid migration model and the Seasonal Area Ratio (SAR) index, respectively.

- The methodology helps overcome spectral mixing challenges in intertidal zones, providing a technical framework for fine-scale vegetation classification and dynamic monitoring in complex wetland environments.

- The revealed spatiotemporal dynamics and competition mechanisms offer critical insights for targeted management of invasive Spartina alterniflora and for the conservation of coastal wetland ecosystems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area, Data Sources, and Methodology

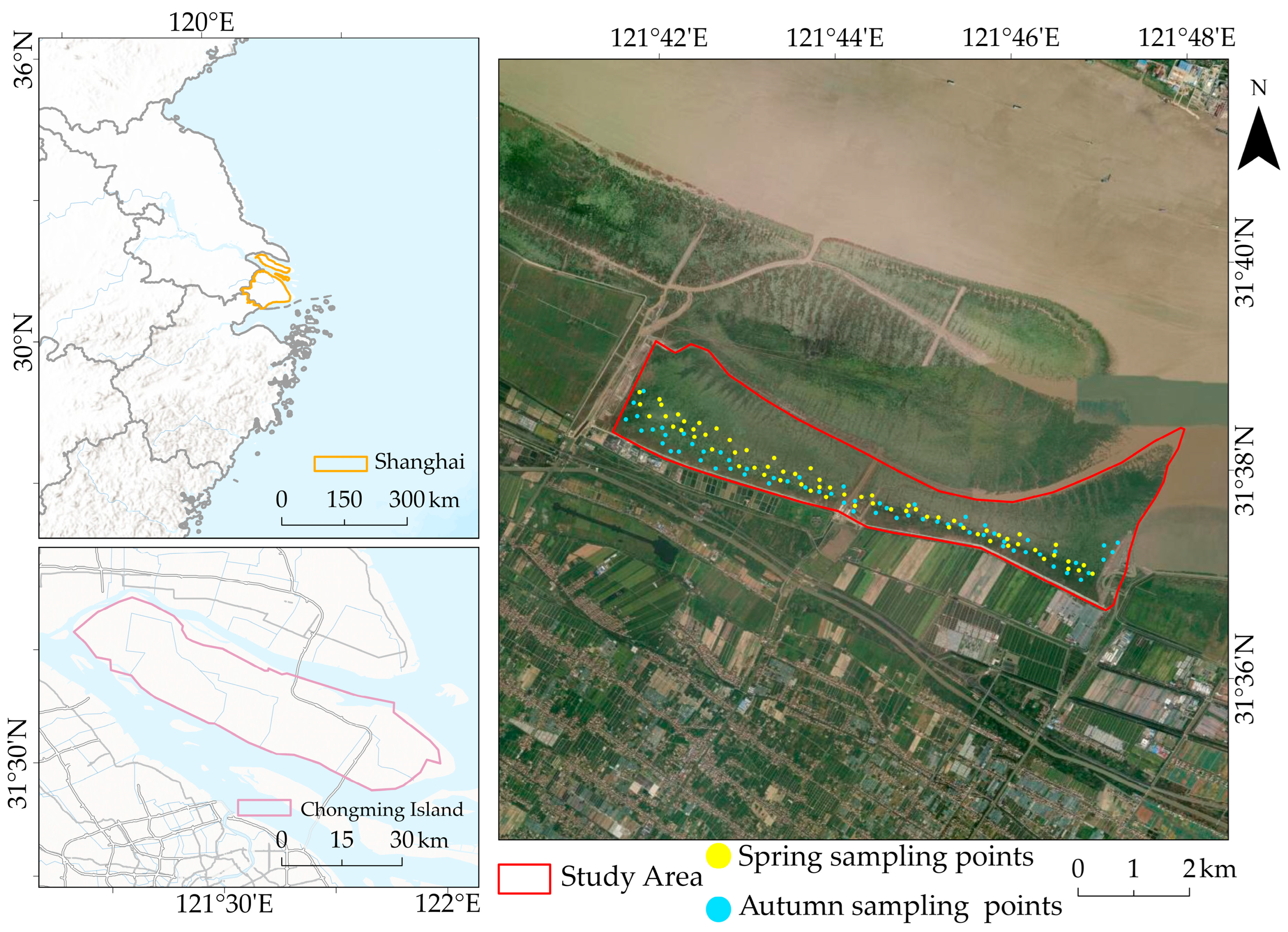

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source and Preprocessing

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Delineation of the Mixed Ecotone

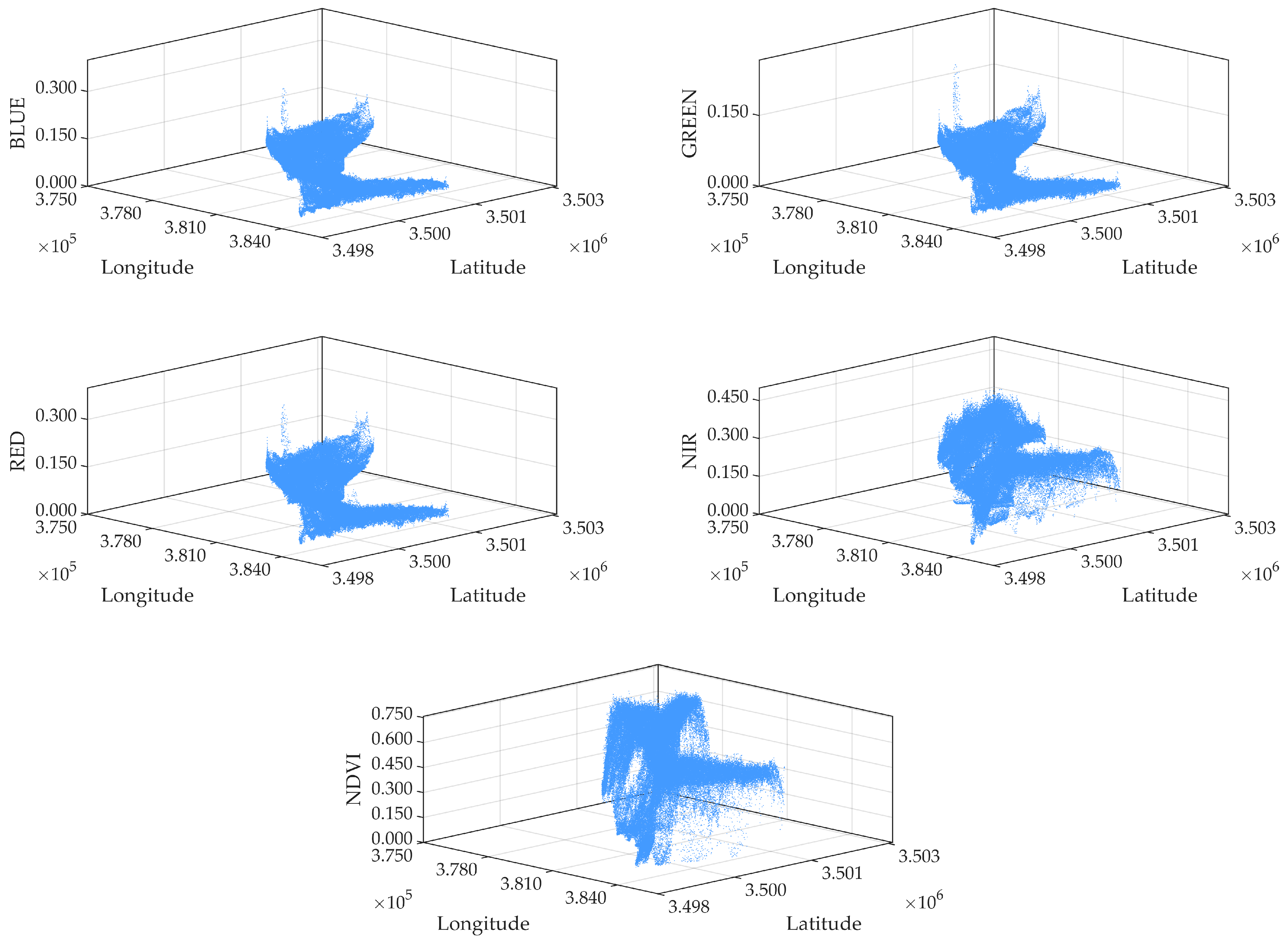

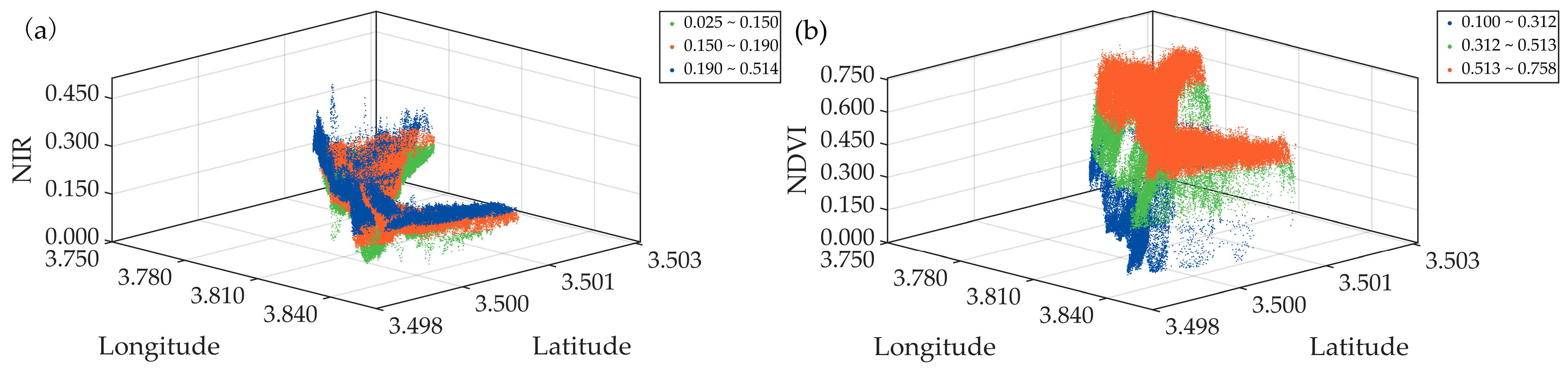

- Spectral Feature Extraction and 3D Feature Space Construction.

- Optimal Spectral Index Selection and Multi-threshold Otsu Segmentation.

- Time-Series Classification and Accuracy Validation.

2.3.2. Spatiotemporal Dynamics Monitoring of the Mixed Ecotone

- Centroid Migration Model.

- Seasonal Area Ratio (SAR) Index.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Selection of Optimal Spectral Indices

3.2. Accuracy Validation of Classification Results

3.3. Inter-Annual Variation in Adaptive Thresholds

3.4. Spatial Distribution Pattern of the Mixed Ecotone

3.5. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Mixed Ecotone

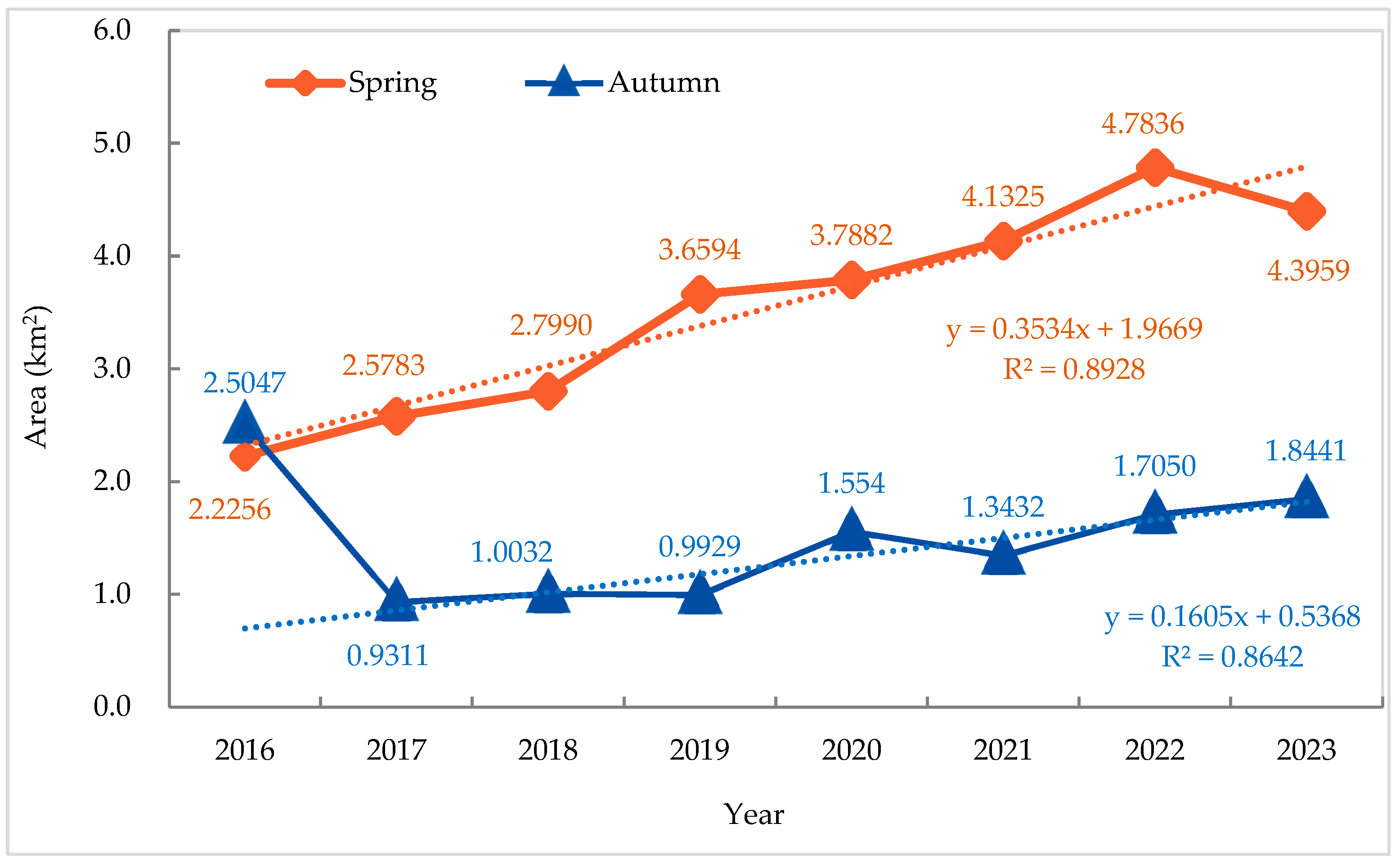

3.5.1. Inter-Annual Variations (2016–2023)

- Analysis of Area Change Trends.

- Centroid Migration Trajectory and Spatial Expansion Pattern.

3.5.2. Intra-Annual Dynamics (Seasonal Variations)

3.6. Method Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodological Innovations and Comparative Analysis

4.2. Ecological Implications and Mechanistic Insights

4.3. Management Implications and Recommendations

- Develop seasonal management strategies based on phenological asynchrony. This involves implementing control measures during S. alterniflora’s physiologically vulnerable periods (e.g., green-up and flowering/fruiting stages) [61], and conducting ecological restoration projects during the spring dominance phase of P. australis. Implementing these strategies can offer synergistic benefits, enhancing management efficacy with minimal ecological disruption.

- Adopt spatially differentiated management strategies. This involves accounting for micro-topographic and salinity gradients [62] to implement tailored strategies for the patchy northwestern ecotone. In the central region, which is affected by human activities, ecological engineering assessments and adaptive restoration planning should be undertaken to mitigate the impacts of infrastructure on vegetation patterns.

- Establish a dynamic monitoring and early-warning system. By integrating multi-source remote sensing data with ground observation networks [63], a model can be developed to capture spatial, phenological, and competitive dynamics, track the expansion of S. alterniflora, and issue early risk alerts, thereby providing decision support for coastal wetland conservation.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

- Adopting advanced analytical techniques—such as object-based image analysis or deep learning—to improve the detection of fine-scale boundaries and heterogeneous landscape features.

- Developing an integrated multi-temporal validation system that combines long-term monitoring plots with UAV-acquired hyperspectral data to improve classification reliability and strengthen the interpretation of ecological processes.

- Implementing spatially explicit models to quantify the combined impacts of anthropogenic drivers (e.g., engineering infrastructure) and natural factors on ecotone dynamics.

- Further validation of the transferability and refinement of the analytical framework is needed. Although the workflow—integrating three-dimensional visualization, optimal spectral index selection, and Otsu thresholding—is conceptually generalizable, applying it to new sites requires recalibrating spectral thresholds based on local conditions. Future research should assess the framework’s performance across a range of coastal wetland systems and explore strategies for deriving spectral indices and threshold rules that are regionally adaptive or broadly applicable to support more extensive ecological monitoring.

5. Conclusions

- A seasonally adaptive spectral index framework, incorporating a three-dimensional feature space, was developed to extract the mixed ecotone. The identification of optimal spectral features—near-infrared reflectance for spring and NDVI for autumn—followed by the use of the multi-threshold Otsu algorithm, enabled accurate vegetation community classification. The validation results showed high accuracy, with an overall accuracy of 87.3 ± 1.4% and a Kappa coefficient of 0.84 ± 0.02. The mixed ecotone was delineated with producers’ and users’ accuracies of 85.2% and 83.6%, respectively, which enhances the identification of narrow transition zones.

- This study documented a land-to-sea ecological sequence—pure P. australis–mixed ecotone–pure S. alterniflora—in the Chongming Dongtan wetland, with the vegetation arranged in an east–west belt. The northwestern sector showed a patchy distribution influenced by tidal creeks and micro-topography, related to salinity gradients and hydrological differentiation caused by elevation heterogeneity. Meanwhile, regular linear features in the central area were associated with engineering infrastructure, indicating spatial heterogeneity shaped by both natural and anthropogenic drivers.

- The mixed ecotone showed seaward expansion from 2016 to 2023. During spring, it showed an average annual growth rate of 13.93%, with the centroid migrating seaward at an azimuth of 112°. The migration rate decreased in later years, with periodic reversals, suggesting possible regulation by hydrological resistance or interspecific competition. Influenced by extreme climate events, the ecotone area showed fluctuations in autumn—most notably a 62.83% decline from 2016 to 2017. The centroid migration path was also complex, following a three-phase sequence of “retreat–leap–expansion.” The spatiotemporal dynamics were influenced by long-term drivers, such as sediment deposition and climate warming, and by short-term factors, including typhoons, salt stress, and hydrological disturbances.

- Analysis of the SAR index showed a tipping point in 2017, when the seasonal competition pattern shifted from one year of autumn dominance to a seven-year phase of spring dominance. During the spring-dominated phase, the SAR values showed a sawtooth-like fluctuation (0.27–0.42) with cyclical low-medium-high shifts, indicating a dynamic equilibrium in which P. australis gains dominance through phenological advancement. Meanwhile, S. alterniflora maintains competitive resilience through niche penetration. The SAR index served as a metric to quantify phenological competition dynamics, revealing a mechanism of coexistence through seasonal niche differentiation between the invasive and native species.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAR | Seasonal Area Ratio |

| JM | Jeffries-Matusita |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| 2D | Two-dimensional |

| S. alterniflora | Spartina alterniflora |

| P. australis | Phragmites australis |

| B. mariqueter | Bolboschoenoplectus mariqueter |

| NIR | Near-Infrared Reflectance |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| NLSD | National Land Survey Data |

| CLCD | China Land Cover Dataset |

| OBIA | Object-Based Image Analysis |

| GF-1 | Gaofen-1satellite |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| MSI | Multispectral Instrument |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| RTK | Real-Time Kinematic |

| MaxLik | Maximum Likelihood |

| Local Std. Dev. | Local Standard Deviation |

| UN | United Nations |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

References

- Zhu, W.Q.; Ren, G.B.; Wang, J.P.; Wang, J.B.; Hu, Y.B.; Lin, Z.Y.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.J.; Li, S.B.; Wang, N. Monitoring the Invasive Plant Spartina alterniflora in Jiangsu Coastal Wetland Using MRCNN and Long-Time Series Landsat Data. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2630. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.L.; Bai, J.H.; Tebbe, C.C.; Huang, L.B.; Jia, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, X.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Q.Q. Spartina alterniflora invasions reduce soil fungal diversity and simplify co-occurrence networks in a salt marsh ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.Y.; Du, X.L.; Li, Y.M.; Tian, J.T.; Chen, Q.; Huang, Y.H.; Lv, W.W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.Q.; et al. Assessment of macrobenthic community function and ecological quality after reclamation in the Changjiang (Yangtze) River Estuary wetland. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Xu, M.; Wang, Z.F.; Yu, C.F.; Lian, B. Invasive Spartina alterniflora in controlled cultivation: Environmental implications of converging future technologies. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Shi, C. Fine-scale mapping of Spartina alterniflora-invaded mangrove forests with multi-temporal WorldView-Sentinel-2 data fusion. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 295, 113690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ning, X.G.; Li, Z.J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.T. Vegetation changes in Yellow River Delta wetlands from 2018 to 2020 using PIE-Engine and short time series Sentinel-2 images. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 977050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döweler, F.; Fransson, J.E.S.; Bader, M.K.F. Linking High-Resolution UAV-Based Remote Sensing Data to Long-Term Vegetation Sampling—A Novel Workflow to Study Slow Ecotone Dynamics. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 840. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Tang, M.D.; Huang, J.; Mei, X.X.; Zhao, H.J. Driving mechanisms and multi-scenario simulation of land use change based on National Land Survey Data: A case in Jianghan Plain, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1422987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.Y.; Pu, W.P.; Dong, J.H. Spatiotemporal Changes of Land Use and Their Impacts on Ecosystem Service Value in the Agro-pastoral Ecotone of Northern China. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 2373–2384. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, H.Y.; Liu, P.D.; Shi, R.H.; Zhang, C. Extracting the transitional zone of Spartina alterniflora and Phragmites australis in the wetland using high-resolution remotely sensed images. J. Geo Inf. Sci. 2017, 19, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, D.; Huang, H.M.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, S.P.; Li, K.; Wei, Z.; Sun, Y.C. Combing satellite and UAV remote sensing to monitor a mangrove-saltmarsh ecotone: A case study from Dandou Sea in Guangxi. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2025, 44, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.W.; Fang, S.B.; Geng, X.L.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, X.W.; Zhang, D.; Li, R.X.; Sun, W.; Wang, X.R. Coastal ecosystem service in response to past and future land use and land cover change dynamics in the Yangtze river estuary. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.M.R.; Hossain, M.S. Using a water index approach to mapping periodically inundated saltmarsh land-cover vegetation and eco-zonation using multi-temporal Landsat 8 imagery. J. Coast. Conserv. 2024, 28, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstruck, L.; Jarmer, T.; Waske, B. Multi-Stage Feature Fusion of Multispectral and SAR Satellite Images for Seasonal Crop-Type Mapping at Regional Scale Using an Adapted 3D U-Net Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Zhou, M.T.; Sui, H.G. DepthCD: Depth prompting in 2D remote sensing imagery change detection. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 227, 145–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.D.; Shi, R.H.; Meng, F.; Liu, J.T.; Yao, G.B.; Fu, P.J. Combining Multi-Indices by Neural Network Model for Estimating Canopy Chlorophyll Content: A Case Study of Interspecies Competition between Spartina alterniflora and Phragmites australis. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2022, 31, 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Najjar Khodabakhsh, Z.; Moradi, H.; Rahimzadeh-Bajgiran, P.; Pourmanafi, S.; Ahmadi, M. A 30-year phenological study of mangrove forests at the species level as a function of climatic drivers using multispectral remote sensing satellites. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klehr, D.; Stoffels, J.; Hill, A.; Pham, V.D.; van der Linden, S.; Frantz, D. Mapping tree species fractions in temperate mixed forests using Sentinel-2 time series and synthetically mixed training data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 323, 114740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomeo, D.; Simis, S.G.H.; Selmes, N.; Jungblut, A.D.; Tebbs, E.J. Colour-informed ecoregion analysis highlights a satellite capability gap for spatially and temporally consistent freshwater cyanobacteria monitoring. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 228, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbier, K.; Hughes, M.G.; Rogers, K.; Woodroffe, C.D. Inundation characteristics of mangrove and saltmarsh in micro-tidal estuaries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2021, 261, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deijns, A.A.J.; Michéa, D.; Déprez, A.; Malet, J.P.; Kervyn, F.; Thiery, W.; Dewitte, O. A semi-supervised multi-temporal landslide and flash flood event detection methodology for unexplored regions using massive satellite image time series. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 215, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siljander, M.; Männistö, S.; Kuoppamäki, K.; Taka, M.; Ruth, O. Urban green space classification using Object-Based Image Analysis (OBIA) and LiDAR fusion: Accuracy evaluation and landscape metrics assessment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 112, 128997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Kumar Panigrahi, R. Texture Classification-Based NLM PolSAR Filter. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 18, 1396–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedzadeh, A.; Setoodeh, P.; Alavi, M.; Habibi, S. Information Extraction Using Spectral Analysis of the Chattering of the Smooth Variable Structure Filter. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 104992–105008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.X.; Hu, H.W.; Yang, P.; Ye, G.P. Spartina alterniflora invasion has a greater impact than non-native species, Phragmites australis and Kandelia obovata, on the bacterial community assemblages in an estuarine wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 822, 153517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.T.; Yang, Z.Q.; Chen, C.P.; Tian, B. Tracking the environmental impacts of ecological engineering on coastal wetlands with numerical modeling and remote sensing. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 113957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hu, Z.; Grandjean, T.J.; Bing Wang, Z.; van Zelst, V.T.M.; Qi, L.; Xu, T.P.; Young Seo, J.; Bouma, T.J. Dynamics and drivers of tidal flat morphology in China. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, B.; Xu, H.F.; Xu, Z.L.; Wei, Z.Z.; Lu, Z.P.; Liu, X. Landscape ecological risk assessment of chongming dongtan wetland in shanghai from 1990 to 2020. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Yang, Q.Q.; Chen, Z.Z.; Lei, J.R.; Wu, T.T.; Li, Y.L.; Pan, X.Y. The interaction between temperature and rainfall determines the probability of tropical forest fire occurrence in Hainan Island. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 8, 1495699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, B. Field practice of Scirpus mariqueter restoration in the bird habitats of Chongming Dongtan Wetland, China. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2023, 34, 2663–2671. [Google Scholar]

- Suwanprasit, C.; Shahnawaz. Mapping burned areas in Thailand using Sentinel-2 imagery and OBIA techniques. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Ning, Y.L.; Li, J.X.; Shi, Z.L.; Zhang, Q.Z.; Li, L.Q.; Kang, B.Y.; Du, Z.B.; Luo, J.C.; He, M.X.; et al. Invasion stage and competition intensity co-drive reproductive strategies of native and invasive saltmarsh plants: Evidence from field data. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, J.L.; Liu, Y.X.; Liu, Y.C.; Liu, R.Q. Plant species classification in salt marshes using phenological parameters derived from Sentinel-2 pixel-differential time-series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 256, 112320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Qu, Y.H. The Retrieval of Ground NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) Data Consistent with Remote-Sensing Observations. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Guo, Z.H.; Liu, L.; Mei, J.C.; Wang, L. Lithological classification using SDGSAT-1 TIS data and three-dimensional spectral feature space model. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2025, 18, 2467983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Z.C.; Hu, Z.W.; Jian, C.L.; Luo, S.J.; Mou, L.C.; Zhu, X.X.; Molinier, M. A Lightweight Deep Learning-Based Cloud Detection Method for Sentinel-2A Imagery Fusing Multiscale Spectral and Spatial Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, M.; Rahimzadeganasl, A. Agricultural Field Detection from Satellite Imagery Using the Combined Otsu’s Thresholding Algorithm and Marker-Controlled Watershed-Based Transform. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2021, 49, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaer, Y.; Shi, Q.D.; Shi, H.B.; Peng, L.; Abudureyimu, A.; Wan, Y.B.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.Q.; Yang, N.J. What Is the Effect of Quantitative Inversion of Photosynthetic Pigment Content in Populus euphratica Oliv. Individual Tree Canopy Based on Multispectral UAV Images? Forests 2022, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Z.; Hong, L. A New Classification Rule-Set for Mapping Surface Water in Complex Topographical Regions Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Water 2024, 16, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.Q.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhang, Q.J.; Niu, Y.F.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, Z. A novel feature selection criterion for wetland mapping using GF-3 and Sentinel-2 Data. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 171, 113146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Lin, X.F.; Fu, D.J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, S.B.; Wang, F.; Wang, C.P.; Xiao, Z.Y.; Shi, Y.Q. Comparison of the Applicability of J-M Distance Feature Selection Methods for Coastal Wetland Classification. Water 2023, 15, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.M.; Woo, H.J.; Hong, W.H.; Seo, H.; Na, W.J. Optimization of Number of GCPs and Placement Strategy for UAV-Based Orthophoto Production. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jin, M.T.; Guo, P. A High-Precision Crop Classification Method Based on Time-Series UAV Images. Agriculture 2023, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motiee, H.; Ahrari, S.; Motiee, S.; McBean, E. Assessment of Climate Change with Remote Sensing Data on Snow and Ice Cover in the Rocky Mountains Glaciers. J. Environ. Inf. 2025, 46, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.H.; Li, Z.Y.; Yim, S.H.L.; Chang, T.Y.; Man, C.L.; Cheng, C.H.; Kwok, T.C.Y.; Ho, K.F. The comparison between multiple linear regression and random forest model in predicting environmental noise and its frequency components level in Hong Kong using a land-use regression approach. Env. Res. 2025, 286, 122919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.M.; Huang, Q.; Huang, S.Z.; Leng, G.Y.; Bai, Q.J.; Liang, H.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Fang, W. Spatial-temporal dynamics of agricultural drought in the Loess Plateau under a changing environment: Characteristics and potential influencing factors. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 244, 106540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.Z.; Cong, N.; Rong, L.; Qi, G.; Du, L.; Ren, P.; Xiao, J.T. Spatiotemporal dynamics and driving mechanisms of alpine peatland wetlands in the eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau based on a Vision Transformer model. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.Y.; Yang, G.H.; Li, Q.Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.H. Distance–Intensity Image Strategy for Pulsed LiDAR Based on the Double-Scale Intensity-Weighted Centroid Algorithm. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haight, J.D.; Hall, S.J.; Lewis, J.S. Landscape modification and species traits shape seasonal wildlife community dynamics within an arid metropolitan region. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2025, 259, 105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Y.J.; Li, J.; Wang, X. Frequency and spatial based multi-layer context network (FSCNet) for remote sensing scene classification. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 128, 103781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Chen, H.Z.; Cui, T.; Li, H.H. SFMRNet: Specific Feature Fusion and Multibranch Feature Refinement Network for Land Use Classification. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 16206–16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florath, J.; Keller, S.; Abarca-del-Rio, R.; Hinz, S.; Staub, G.; Weinmann, M. Glacier Monitoring Based on Multi-Spectral and Multi-Temporal Satellite Data: A Case Study for Classification with Respect to Different Snow and Ice Types. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.B.; Lin, Z.Y.; Ma, Y.Q.; Ren, G.B.; Xu, Z.J.; Song, X.K.; Ma, Y.; Wang, A.D.; Zhao, Y.J. Distribution and invasion of Spartina alterniflora within the Jiaozhou Bay monitored by remote sensing image. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.L.; Zhao, X.Y.; Huang, W.D.; Zhan, J.; He, Y.Z. Drought Stress Influences the Growth and Physiological Characteristics of Solanum rostratum Dunal Seedlings From Different Geographical Populations in China. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 733268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Liang, G.P.; Wang, C.K.; Zhou, Z.H. Asynchronous seasonal patterns of soil microorganisms and plants across biomes: A global synthesis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 175, 108859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisner, A.; Segrestin, J.; Konečná, M.; Blažek, P.; Janíková, E.; Applová, M.; Švancárová, T.; Lepš, J. Why are plant communities stable? Disentangling the role of dominance, asynchrony and averaging effect following realistic species loss scenario. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 1832–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Grandjean, T.J.; Wu, X.R.; van de Koppel, J.; van der Wal, D. Long-term phenological shifts in coastal saltmarsh vegetation reveal complex responses to climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 179, 114219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, J.Q.; Chen, L.J.; He, H.Q.; Han, X.X. Revealing the long-term impacts of plant invasion and reclamation on native saltmarsh vegetation in the Yangtze River estuary using multi-source time series remote sensing data. Ecol. Eng. 2024, 208, 107362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrowski, M.; Bechtel, B.; Böhner, J.; Oldeland, J.; Weidinger, J.; Schickhoff, U. Application of Thermal and Phenological Land Surface Parameters for Improving Ecological Niche Models of Betula utilis in the Himalayan Region. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Han, M.; Han, G.X.; Wang, M.; Tian, L.X.; Zhu, J.Q.; Kong, X.L. Reclamation-oriented spatiotemporal evolution of coastal wetland along Bohai Rim, China. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2022, 41, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, Y.L.; Yuan, L.; Zhong, Q.C. Climate warming increases the invasiveness of the exotic Spartina alterniflora in a coastal salt marsh: Implications for invasion management. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 124765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.W.; Bai, J.H.; Wang, W.; Ma, X.; Guan, Y.N.; Gu, C.H.; Zhang, S.Y.; Lu, F. Micro-Topography Manipulations Facilitate Suaeda Salsa Marsh Restoration along the Lateral Gradient of a Tidal Creek. Wetlands 2020, 40, 1657–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.S.; Wang, Z.L.; Liu, Y. Ecological risk assessment of a coastal area using multi-source remote sensing images and in-situ sample data. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Dong, Y.Y.; Zhu, Y.N.; Huang, W.J. Remote Sensing Inversion of Vegetation Parameters With IPROSAIL-Net. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Spring Image Date | Cloud Cover | Autumn Image Date | Cloud Cover |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 25 March 2016 | 7.8% | 07 December 2016 | 0.2% |

| 2017 | 29 April 2017 | 6.9% | 15 November 2017 | 3.1% |

| 2018 | 01 April 2018 | 7.3% | 12 December 2018 | 6.0% |

| 2019 | 06 April 2019 | 0.6% | 15 November 2019 | 0.0% |

| 2020 | 13 April 2020 | 4.9% | 29 November 2020 | 1.4% |

| 2021 | 18 April 2021 | 4.6% | 14 November 2021 | 0.0% |

| 2022 | 20 April 2022 | 2.8% | 16 November 2022 | 8.4% |

| 2023 | 28 April 2023 | 6.5% | 24 November 2023 | 8.7% |

| Season | Spectral Index | Threshold T1 | Threshold T2 | JM Distance (Average) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | ρBLUE | 0.040600 | 0.094005 | 1.50 |

| ρGREEN | 0.066416 | 0.123075 | 1.60 | |

| ρRED | 0.075696 | 0.129511 | 1.70 | |

| ρNIR | 0.149945 | 0.190183 | 1.99 | |

| NDVI | 0.174555 | 0.282613 | 1.86 | |

| Autumn | ρBLUE | 0.066783 | 0.104831 | 1.40 |

| ρGREEN | 0.043947 | 0.074789 | 1.50 | |

| ρRED | 0.072376 | 0.119112 | 1.60 | |

| ρNIR | 0.181992 | 0.258286 | 1.80 | |

| NDVI | 0.311753 | 0.513176 | 1.93 |

| Year | Season | Overall Accuracy (%) | Kappa Coefficient | Mixed Ecotone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer’s Accuracy (%) | User’s Accuracy (%) | ||||

| 2016 | Spring | 85.5 | 0.82 | 83.8 | 82.0 |

| Autumn | 86.0 | 0.83 | 84.5 | 82.8 | |

| 2017 | Spring | 86.8 | 0.83 | 85.0 | 83.5 |

| Autumn | 85.2 | 0.81 | 82.5 | 80.9 | |

| 2018 | Spring | 87.2 | 0.84 | 85.5 | 84.0 |

| Autumn | 87.8 | 0.85 | 86.0 | 84.5 | |

| 2019 | Spring | 88.0 | 0.85 | 86.3 | 85.0 |

| Autumn | 87.0 | 0.84 | 85.0 | 83.2 | |

| 2020 | Spring | 88.5 | 0.86 | 87.0 | 85.8 |

| Autumn | 87.3 | 0.84 | 85.2 | 83.5 | |

| 2021 | Spring | 88.9 | 0.86 | 87.5 | 86.2 |

| Autumn | 88.2 | 0.85 | 86.3 | 84.8 | |

| 2022 | Spring | 89.2 | 0.87 | 88.0 | 86.5 |

| Autumn | 88.5 | 0.86 | 86.8 | 85.0 | |

| 2023 | Spring | 89.5 | 0.86 | 86.2 | 85.0 |

| Autumn | 88.7 | 0.87 | 85.8 | 84.5 | |

| Average ± StdDev (%) | 87.3 ± 1.4 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 85.2 ± 1.5 | 83.6 ± 1.7 | |

| Year | Spring (NIR) Threshold T1 | Spring (NIR) Threshold T2 | Autumn (NDVI) Threshold T1 | Autumn (NDVI) Threshold T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 0.2700 | 0.2981 | 0.2865 | 0.4263 |

| 2017 | 0.2500 | 0.2722 | 0.2778 | 0.3830 |

| 2018 | 0.2383 | 0.2629 | 0.3039 | 0.4149 |

| 2019 | 0.2462 | 0.2685 | 0.2402 | 0.3077 |

| 2020 | 0.2382 | 0.2982 | 0.2695 | 0.3767 |

| 2021 | 0.2531 | 0.2830 | 0.2979 | 0.4096 |

| 2022 | 0.2828 | 0.3411 | 0.4533 | 0.6179 |

| 2023 | 0.1499 | 0.1902 | 0.3118 | 0.5131 |

| Year | Spring Area | Annual Spring Change Rate | Autumn Area | Annual Autumn Change Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 2.2256 | — | 2.5047 | — |

| 2017 | 2.5783 | 15.85 | 0.9311 | −62.83 |

| 2018 | 2.7990 | 8.56 | 1.0032 | 7.74 |

| 2019 | 3.6594 | 30.74 | 0.9929 | −1.03 |

| 2020 | 3.7882 | 3.52 | 1.5540 | 56.51 |

| 2021 | 4.1325 | 9.09 | 1.3432 | −13.56 |

| 2022 | 4.7836 | 15.76 | 1.7050 | 26.94 |

| 2023 | 4.3959 | −8.10 | 1.8441 | 8.16 |

| Method | Overall Accuracy (%) | Kappa Coefficient | Mixed Ecotone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer’s Accuracy (%) | User’s Accuracy (%) | |||

| Proposed Method | 88.7 | 0.87 | 85.8 | 84.5 |

| NDVI + MaxLik | 83.2 | 0.79 | 78.1 | 76.4 |

| NDVI + Otsu (Fixed) | 85.1 | 0.81 | 80.5 | 79.2 |

| NDVI + K-Means | 80.5 | 0.76 | 74.3 | 72.9 |

| NDVI + OBIA | 84.6 | 0.80 | 81.2 | 77.8 |

| NDVI + Filter + Otsu | 82.9 | 0.78 | 76.7 | 75.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hou, W.; Xu, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Dong, T.; Xi, B.; Zhang, Z. Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Spartina alterniflora–Phragmites australis Mixed Ecotone in Chongming Dongtan Wetland Using an Integrated Three-Dimensional Feature Space and Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030454

Hou W, Xu X, Chen X, Li Q, Dong T, Xi B, Zhang Z. Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Spartina alterniflora–Phragmites australis Mixed Ecotone in Chongming Dongtan Wetland Using an Integrated Three-Dimensional Feature Space and Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(3):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030454

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Wan, Xiaoyu Xu, Xiyu Chen, Qianyu Li, Ting Dong, Bao Xi, and Zhiyuan Zhang. 2026. "Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Spartina alterniflora–Phragmites australis Mixed Ecotone in Chongming Dongtan Wetland Using an Integrated Three-Dimensional Feature Space and Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation" Remote Sensing 18, no. 3: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030454

APA StyleHou, W., Xu, X., Chen, X., Li, Q., Dong, T., Xi, B., & Zhang, Z. (2026). Monitoring Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Spartina alterniflora–Phragmites australis Mixed Ecotone in Chongming Dongtan Wetland Using an Integrated Three-Dimensional Feature Space and Multi-Threshold Otsu Segmentation. Remote Sensing, 18(3), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18030454