GCOM-C/SGLI-Based Optical-Water-Type Classification with Emphasis on Discriminating Phytoplankton Bloom Types

Highlights

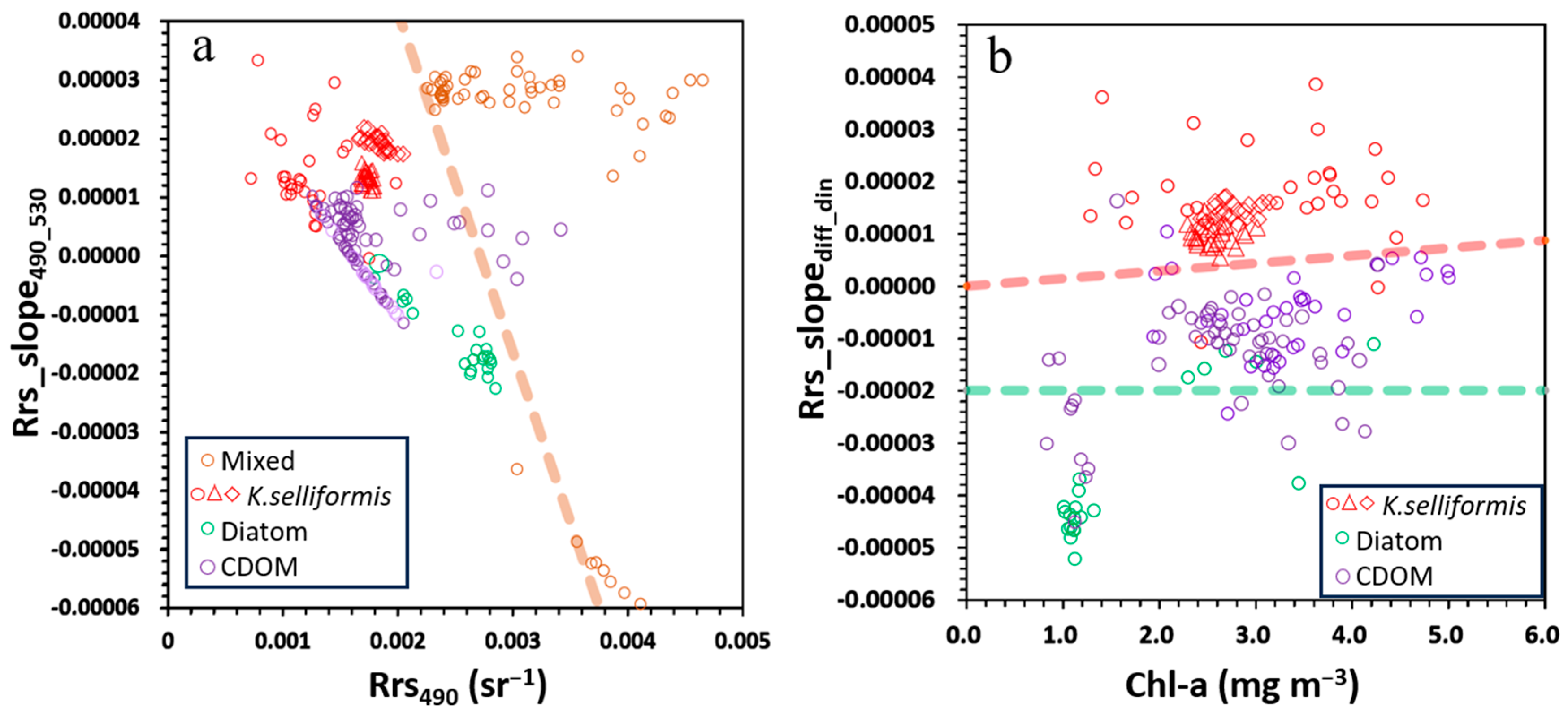

- Rrs spectral shapes within 443–530 nm effectively distinguish dinoflagellate K. selliformis from diatom blooms using SGLI data.

- A method was developed to discriminate dinoflagellate K. selliformis and diatom blooms at different bloom intensities.

- By implementing the proposed optical water type classification method, the Earth-observation-based red tide detection and monitoring become possible.

- Red tide detection and monitoring are possible to reduce and mitigate red-tide-induced socioeconomic adverse impacts.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Satellite and In Situ Data

| Sub- Region | Site Name | Latitude (°N) | Longitude (°E) | Location Symbol | Observation Date | Dominant Phytoplankton (%) | Cell Density (103 Cells L−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TokBay | St. 25 | 35.56 | 139.82 | △ | 1 June 2021 | Diatom (83%) Skeletonema sp. (77%) | 44,147 |

| St. 35 | 35.51 | 139.85 | ○ | Diatom (86%) Skeletonema sp. (78%) | 43,227 | ||

| St. 22 | 35.58 | 139.89 | □ | Diatom (42%) Dinoflagellate (46%) | 11,144 | ||

| SeaKam | - | 50.85 | 156.68 | ◇<5 | 12 October 2020 | Dinoflagellate (100%) K. selliformis (100%) | 162 |

| 51.10 | 157.07 | ○ | Dinoflagellate (100%) K. selliformis (100%) | 482 | |||

| 51.51 | 157.74 | △<5 | Dinoflagellate (100%) K. selliformis (99%) | 254 | |||

| 52.73 | 158.54 | □ | 13 October 2020 | Dinoflagellate (100%) K. selliformis (99%) | 622 | ||

| 52.50 | 159.80 | + | 12 October 2020 | Expected to be dinoflagellate K. selliformis ** | ** | ||

| 51.11 | 158.10 | ||||||

| SoHok | - | 40.20 | 146.20 | + | 1 April 2023 | Expected to be diatom ** | ** |

| 40.10 | 145.00 | ||||||

| 42.00 | 143.90 | ||||||

| 41.50 | 143.80 | ||||||

| 42.00 | 141.48 | ||||||

| 41.00 | 144.00 |

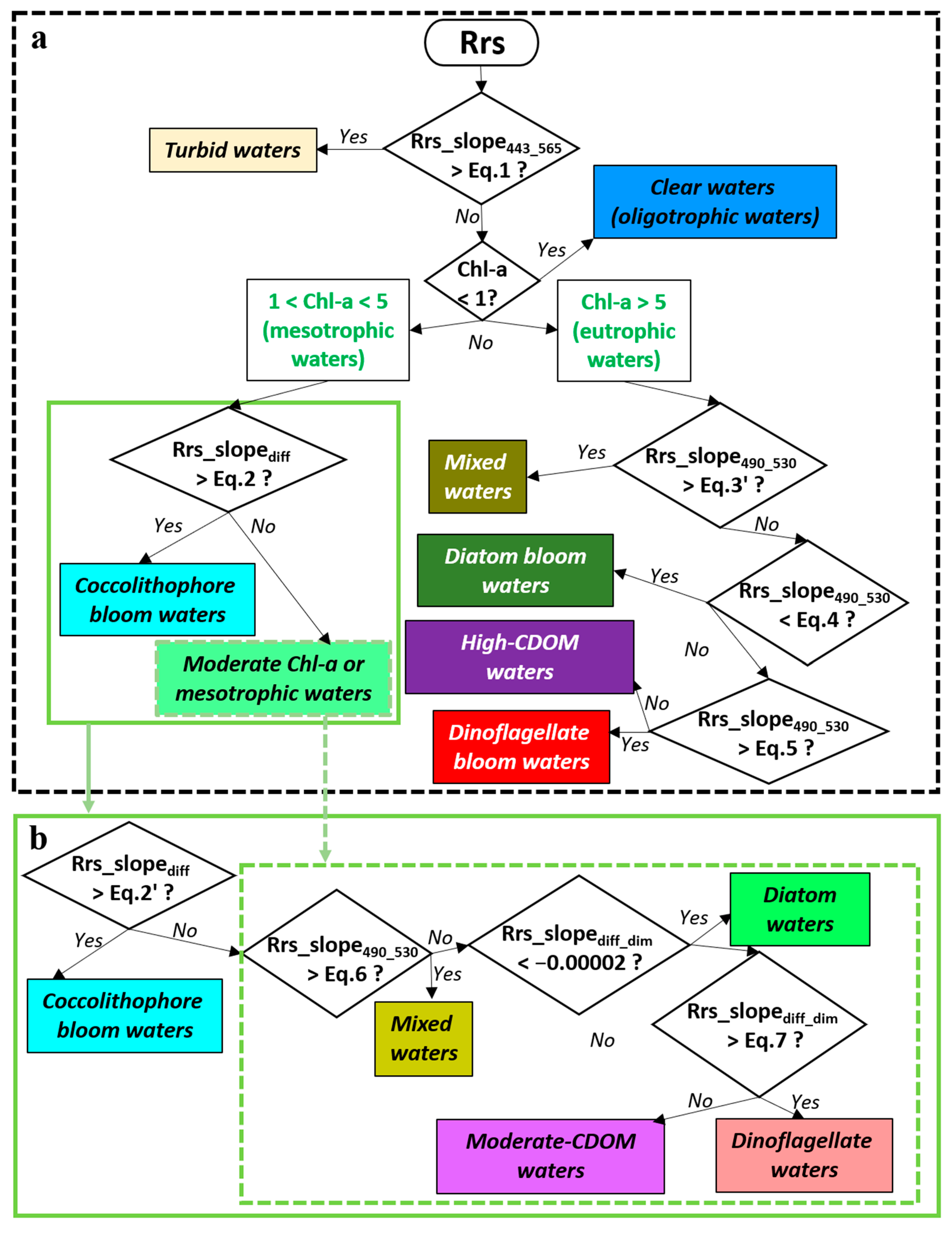

2.2. Previous Approach and Binary Logistic Regression

- Turbid water classification: Turbid waters (high TSSs) were separated from other OWTs using Equation (1):where Rrs_slope443_565 is the slope of Rrs between 443 nm and 565 nm.Rrs_slope443_565 = (2.00 × 10−5) × ln(Chl-a) + (2.00 × 10−5)

- Trophic state classification: Non-turbid waters were categorised into three trophic states based on Chl-a: oligotrophic (low Chl-a < 1 mg m−3), mesotrophic (moderate Chl-a, 1–5 mg m−3), and eutrophic (high Chl-a > 5 mg m−3). Threshold of Chl-a > 5 mg m−3 to classify eutrophic waters, as previous works defined waters with satellite Chl-a > 5 mg m−3 are susceptible to eutrophication and red tide outbreaks [11,21].

- Mesotrophic water classification: Mesotrophic waters were divided into phytoplankton coccolithophore blooms and general mesotrophic waters using Equation (2):Rrs_slopediff = −0.097 × Rrs412 + (5.00 × 10−4)

- Eutrophic mixed water classification: Mixed waters in eutrophic environments were identified using Equation (3):Rrs_slope490_530 = −0.03 × Rrs490 + (8.00 × 10−5)

- Phytoplankton bloom types and high-CDOM water classification in eutrophic waters: The waters were classified as diatom blooms when Rrs_slope490_530 < 0.000003, as dinoflagellate blooms when Rrs490 < 0.0013, and high-CDOM waters for all remaining cases.

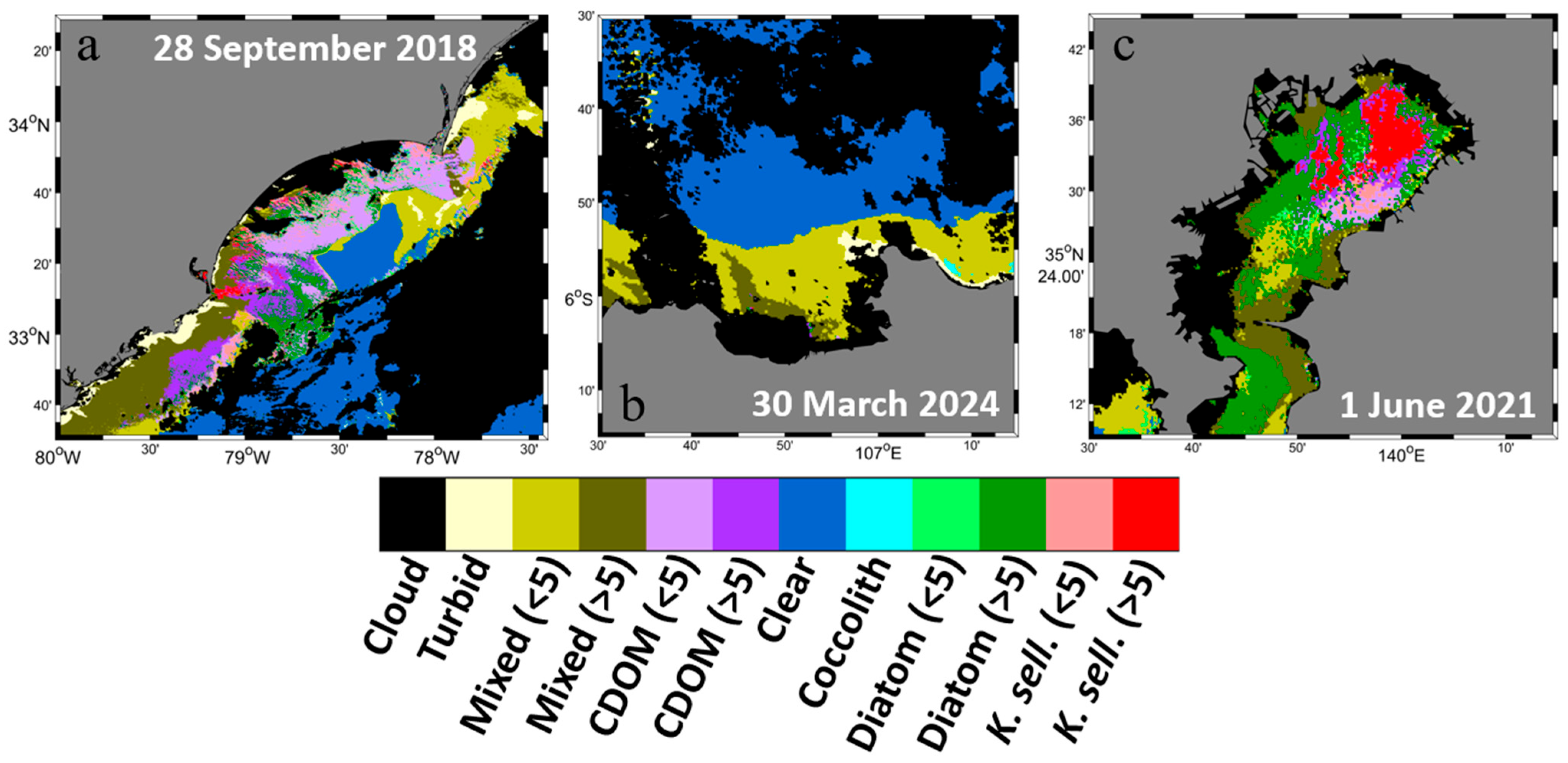

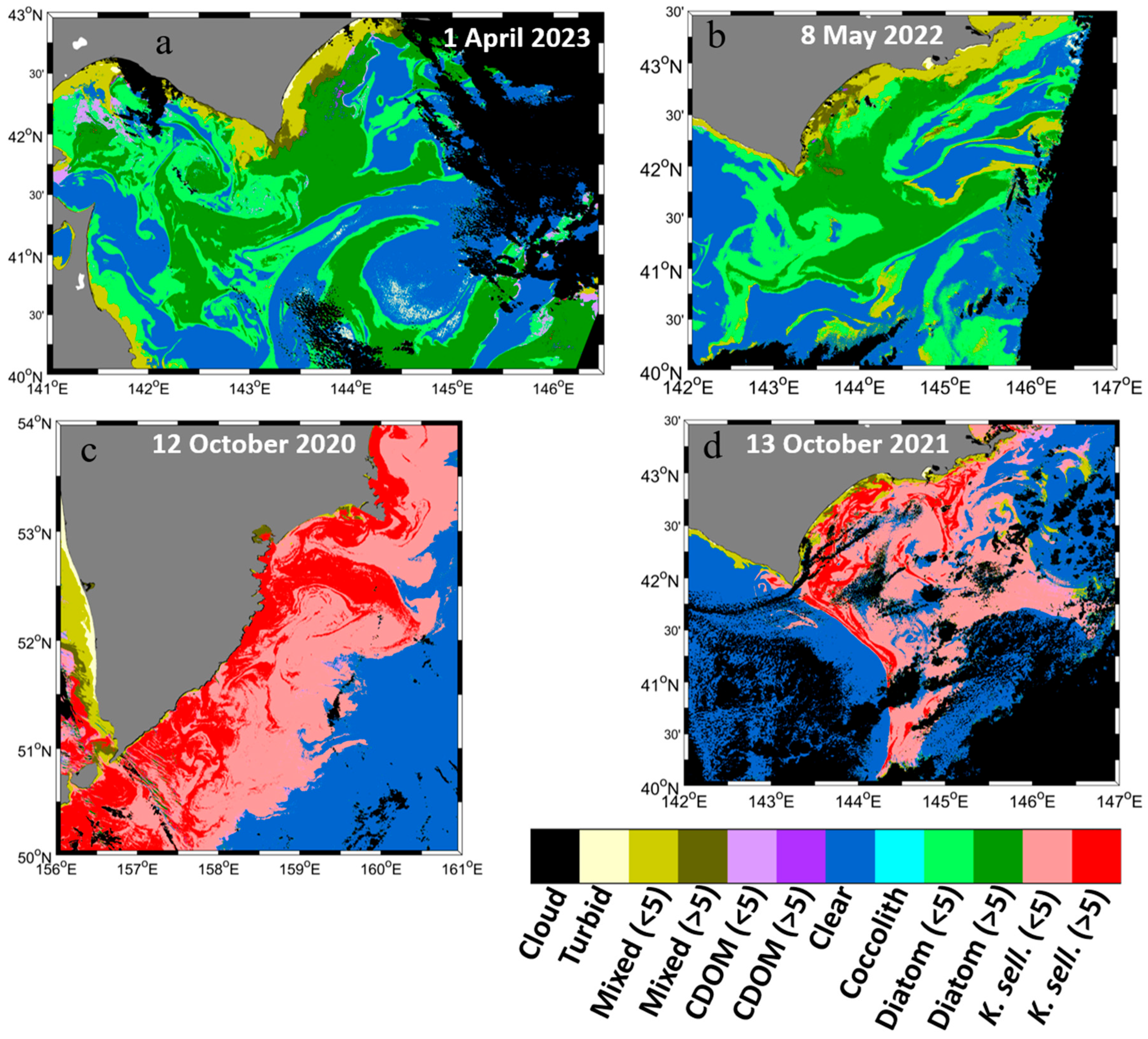

3. Results

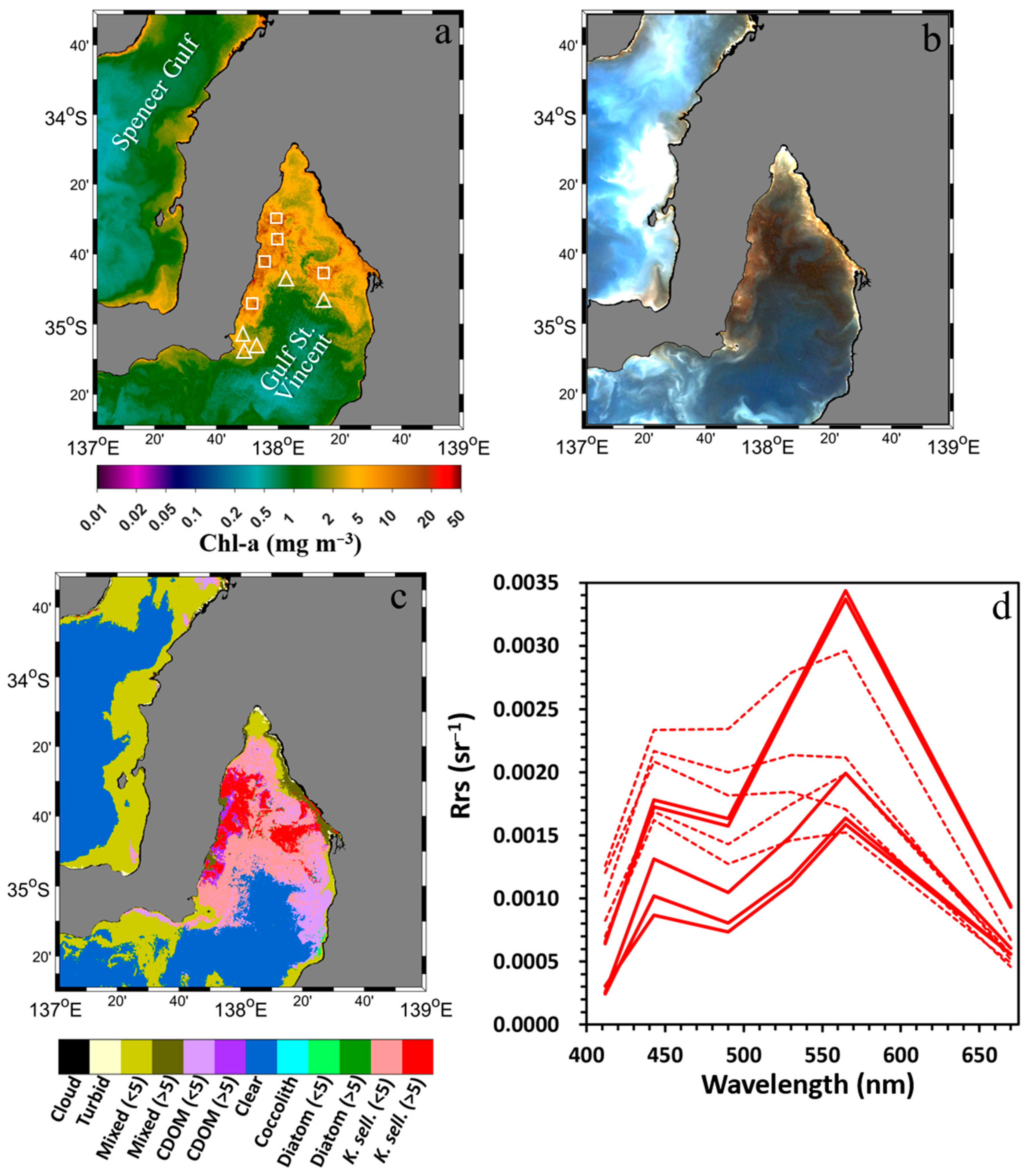

3.1. SGLI-Retrieved Chlorophyll-a and Enhanced Red–Green–Blue Composite

3.2. Apparent Optical Properties of Waters During K. selliformis and Diatom Blooms

3.3. Robustness and Refinement of Classification Criteria

3.4. Improved Optical Water Type Classification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morel, A.; Prieur, L. Analysis of variations in ocean color1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1977, 22, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, T.S.; Campbell, J.W.; Dowell, M.D. A class-based approach to characterizing and mapping the uncertainty of the MODIS ocean chlorophyll product. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, M.; Mikelsons, K.; Jiang, L.; Kratzer, S.; Lee, Z.; Moore, T.; Sosik, H.M.; Van der Zande, D. Global satellite water classification data products over oceanic, coastal, and inland waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 282, 113233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siswanto, E. Assessing optical water types in Asian coastal ocean waters from space using GCOM-C/SGLI observations. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 2337–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziveri, P.; de Bernardi, B.; Baumann, K.H.; Stoll, H.M.; Mortyn, P.G. Sinking of coccolith carbonate and potential contribution to organic carbon ballasting in the deep ocean. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2007, 54, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilling, K.; Kremp, A.; Klais, R.; Olli, K.; Tamminen, T. Spring bloom community change modifies carbon pathways and C:N:P: Chl a stoichiometry of coastal material fluxes. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 7275–7289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tréguer, P.; Bowler, C.; Moriceau, B.; Dutkiewicz, S.; Gehlen, M.; Aumont, O.; Bittner, L.; Dugdale, R.; Finkel, Z.; Iudicone, D.; et al. Influence of diatom diversity on the ocean biological carbon pump. Nat. Geosci. 2017, 11, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, T.; Yuan, H.; Li, H.; Yu, L.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, L.; Huang, B.; Liu, G. Sediment Trap Study Reveals Dominant Contribution of Metazoans and Dinoflagellates to Carbon Export and Dynamic Impacts of Microbes in a Subtropical Marginal Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2021JG006695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrenfeld, M.J.; Falkowski, P.G. Photosynthetic rates derived from satellite-based chlorophyll concentration. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1997, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameda, T.; Ishizaka, J. Size-fractionated primary production estimated by a two-phytoplankton community model applicable to ocean color remote sensing. J. Oceanogr. 2005, 61, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Raús Maúre, E.; Terauchi, G.; Ishizaka, J.; Clinton, N.; DeWitt, M. Globally consistent assessment of coastal eutrophication. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siswanto, E.; Tang, J.; Yamaguchi, H.; Ahn, Y.H.; Ishizaka, J.; Yoo, S.; Kim, S.W.; Kiyomoto, Y.; Yamada, K.; Chiang, C.; et al. Empirical ocean-color algorithms to retrieve chlorophyll-a, total suspended matter, and colored dissolved organic matter absorption coefficient in the Yellow and East China Seas. J. Oceanogr. 2011, 67, 627–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.H.; Peters, D.M.; Kaufman, P.L. Seasonal variability of SeaWiFS chlorophyll a in the Malacca Straits in relation to Asian monsoon. Cont. Shelf Res. 2006, 26, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Taniuchi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Azumaya, T.; Hasegawa, N. Distribution of Harmful Algae (Karenia spp.) in October 2021 Off Southeast Hokkaido, Japan. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 841364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geider, R.J. Light and Temperature Dependence of the Carbon to Chlorophyll a Ratio in Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Implications for Physiology and Growth of Phytoplankton. New Phytol. 1987, 106, 1–34. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2434683 (accessed on 7 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Siswanto, E.; Ishizaka, J.; Tripathy, S.C.; Miyamura, K. Detection of harmful algal blooms of Karenia mikimotoi using MODIS measurements: A case study of Seto-Inland Sea, Japan. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 129, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toratani, M.; Ogata, K.; Fukushima, H. SGLI Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document Atmospheric Correction Algorithm for Ocean Color; Tokai University: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, H.; Antoine, D.; Vellucci, V.; Frouin, R. System vicarious calibration of GCOM-C/SGLI visible and near-infrared channels. J. Oceanogr. 2022, 78, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexanin, A.; Kachur, V.; Khramtsova, A.; Orlova, T. Methodology and Results of Satellite Monitoring of Karenia Microalgae Blooms, That Caused the Ecological Disaster off Kamchatka Peninsula. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, H.; Toya, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nishioka, J.; Hasegawa, D.; Taniuchi, Y.; Kuwata, A. Influence of Coastal Oyashio water on massive spring diatom blooms in the Oyashio area of the North Pacific Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2019, 175, 328–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Wu, J.; Huang, B.; Lin, G.; Lee, Z.; Liu, J.; Shang, S. A new approach to discriminate dinoflagellate from diatom blooms from space in the East China Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2014, 119, 4653–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luang-on, J.; Ishizaka, J.; Buranapratheprat, A.; Phaksopa, J.; Goes, J.I.; Maúre, E.d.R.; Siswanto, E.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, Q.; Nakornsantiphap, P.; et al. MODIS-derived green Noctiluca blooms in the upper Gulf of Thailand: Algorithm development and seasonal variation mapping. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1031901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luang-on, J.; Siswanto, E.; Ogata, K.; Toratani, M.; Buranapratheprat, A.; Leenawarat, D.; Ishizaka, J. Enhancing the reliability of GCOM-C/SGLI data for red tide detection in the upper Gulf of Thailand. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 15, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, J.; King, J.E. Binary Logistic Regression. In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 358–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çokluk, Ö. Logistic Regression: Concept and Application; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mallinis, G.; Koutsias, N. Spectral and Spatial-Based Classification for Broad-Scale Land Cover Mapping Based on Logistic Regression. Sensors 2008, 8, 8067–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Muller-Karger, F.E.; Taylor, C.; Carder, K.L.; Kelble, C.; Johns, E.; Heil, C.A. Red tide detection and tracing using MODIS fluorescence data: A regional example in SW Florida coastal waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paerl, R.W.; Venezia, R.E.; Sanchez, J.J.; Paerl, H.W. Picophytoplankton dynamics in a large temperate estuary and impacts of extreme storm events. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, T.S.; Dowell, M.D.; Franz, B.A. Detection of coccolithophore blooms in ocean color satellite imagery: A generalized approach for use with multiple sensors. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, T.; Mizobata, K.; Saitoh, S.I. Interannual variability of coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi blooms in response to changes in water column stability in the eastern Bering Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2012, 34, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebel, R.; Brupbacher, U.; Schmidtko, S.; Nausch, G.; Waniek, J.J.; Thierstein, H.-R. Spring coccolithophore production and dispersion in the temperate eastern North Atlantic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, 8030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.I.; Toratani, M.; Higa, H.; Son, S.H.; Siswanto, E.; Ishizaka, J. Long-Term Evaluation of GCOM-C/SGLI Reflectance and Water Quality Products: Variability Among JAXA G-Portal and JASMES. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, F.; Zhao, H.; Sun, X.; Zhu, Q.; Li, M. Optical distinguishability of phytoplankton species and its implications for hyperspectral remote sensing discrimination potential. J. Sea Res. 2024, 202, 102540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wouthuyzen, S. Measuring Sea SURFACE Salinity of the Jakarta Bay Using Remotely Sensed of Ocean Color Data Acquired by Modis Sensor. Mar. Res. Indones. 2015, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaempf, J. Prediction of the Spreading of an Unprecedented Karenia Mikimotoi Bloom in South Australian Gulfs. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, Y.; Smith, S.L.; Siswanto, E.; Sasaki, H.; Nonaka, M. Physiological flexibility of phytoplankton impacts modelled chlorophyll and primary production across the North Pacific Ocean. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 4865–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavatta, S.; Brewin, R.J.W.; Skákala, J.; Polimene, L.; de Mora, L.; Artioli, Y.; Allen, J.I. Assimilation of Ocean-Color Plankton Functional Types to Improve Marine Ecosystem Simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2018, 123, 834–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, M.C.; Sasai, Y.; Siswanto, E.; Kuwano-Yoshida, A.; Aiki, H.; Cronin, M.F. Impact of cyclonic eddies and typhoons on biogeochemistry in the oligotrophic ocean based on biogeochemical/physical/meteorological time-series at station KEO. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2018, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Rodríguez, M.D.; Brown, C.W.; Doney, S.C.; Kleypas, J.; Kolber, D.; Kolber, Z.; Hayes, P.K.; Falkowski, P.G. Representing key phytoplankton functional groups in ocean carbon cycle models: Coccolithophorids. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16, 47-1–47-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Calle, S.; Gnanadesikan, A.; Del Castillo, C.E.; Balch, W.M.; Guikema, S.D. Multidecadal increase in North Atlantic coccolithophores and the potential role of rising CO2. Science 2015, 350, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouw, C.B.; Yoder, J.A. Optical determination of phytoplankton size composition from global SeaWiFS imagery. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, 12018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Siswanto, E. GCOM-C/SGLI-Based Optical-Water-Type Classification with Emphasis on Discriminating Phytoplankton Bloom Types. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020334

Siswanto E. GCOM-C/SGLI-Based Optical-Water-Type Classification with Emphasis on Discriminating Phytoplankton Bloom Types. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020334

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiswanto, Eko. 2026. "GCOM-C/SGLI-Based Optical-Water-Type Classification with Emphasis on Discriminating Phytoplankton Bloom Types" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020334

APA StyleSiswanto, E. (2026). GCOM-C/SGLI-Based Optical-Water-Type Classification with Emphasis on Discriminating Phytoplankton Bloom Types. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 334. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020334