Seasonal and Interannual Variation in Martian Gravity Waves at Different Altitudes from the Mars Climate Sounder

Highlights

- Based on observational data, this study reveals that gravity waves with vertical wavelengths ranging from 9 to 15 km exhibit complex global distributions at altitudes between 10 and 70 km. In addition, these distributions exhibit night–day variations, as well as seasonal and interannual variations.

- The global distribution and seasonal and interannual variations in gravity waves are associated with topography, polar jets, and large dust storms.

- The interannual variations in gravity waves imply that, in addition to the known large dust storms, complex interannual variations may also exist in atmospheric activity over the polar jets and complex topography at mid-to-low latitudes on Mars.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Global Distribution of GW Activity

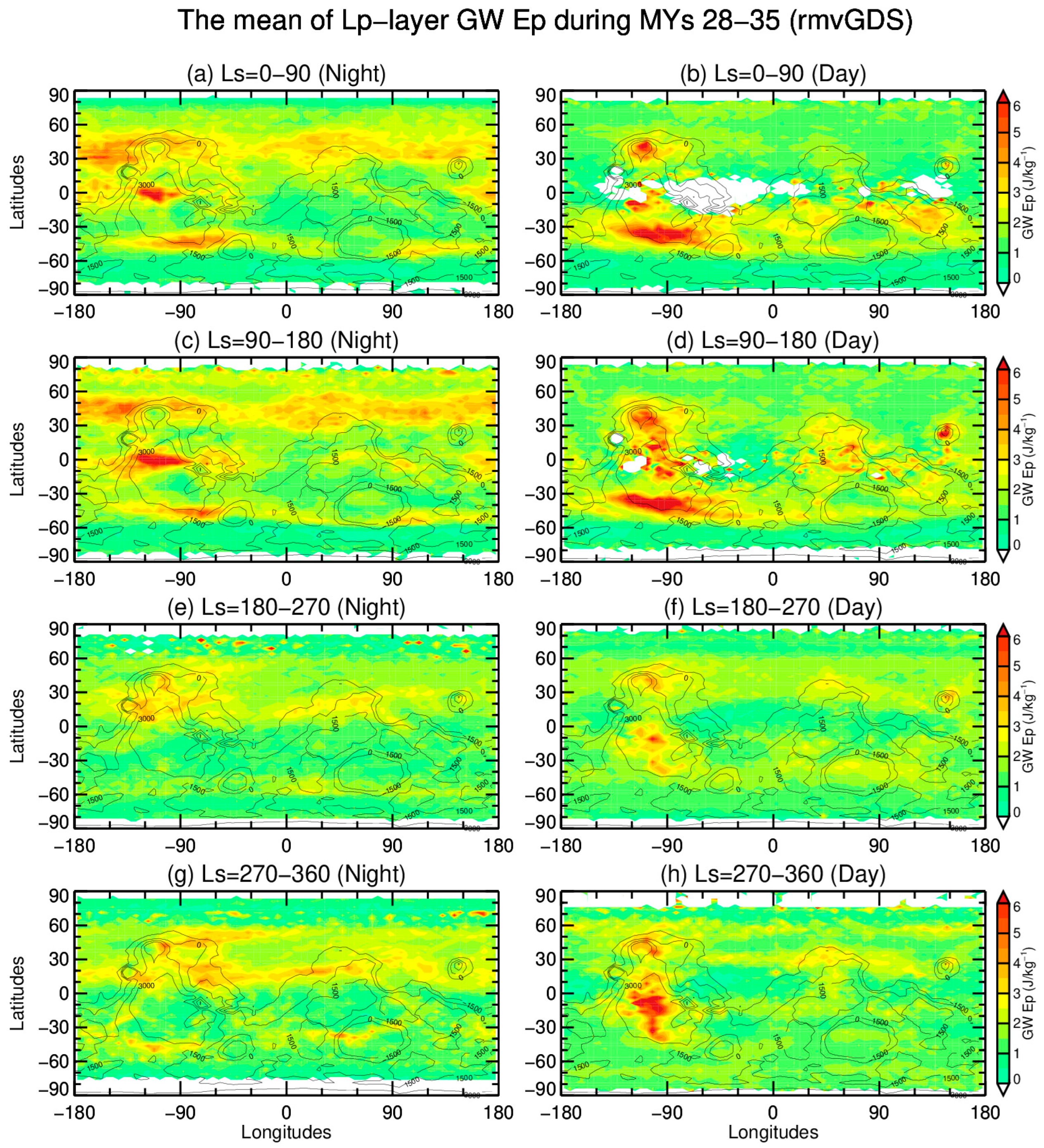

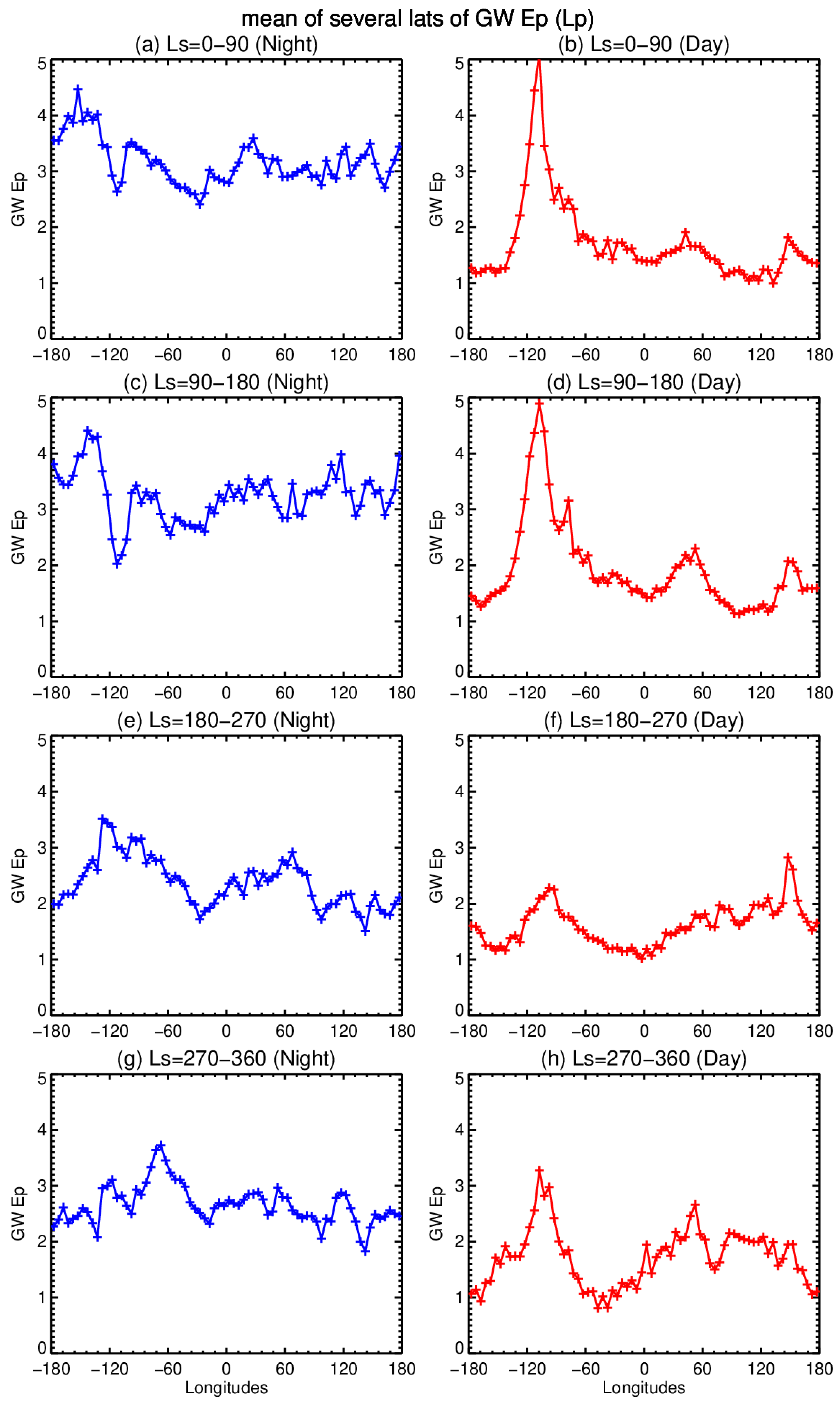

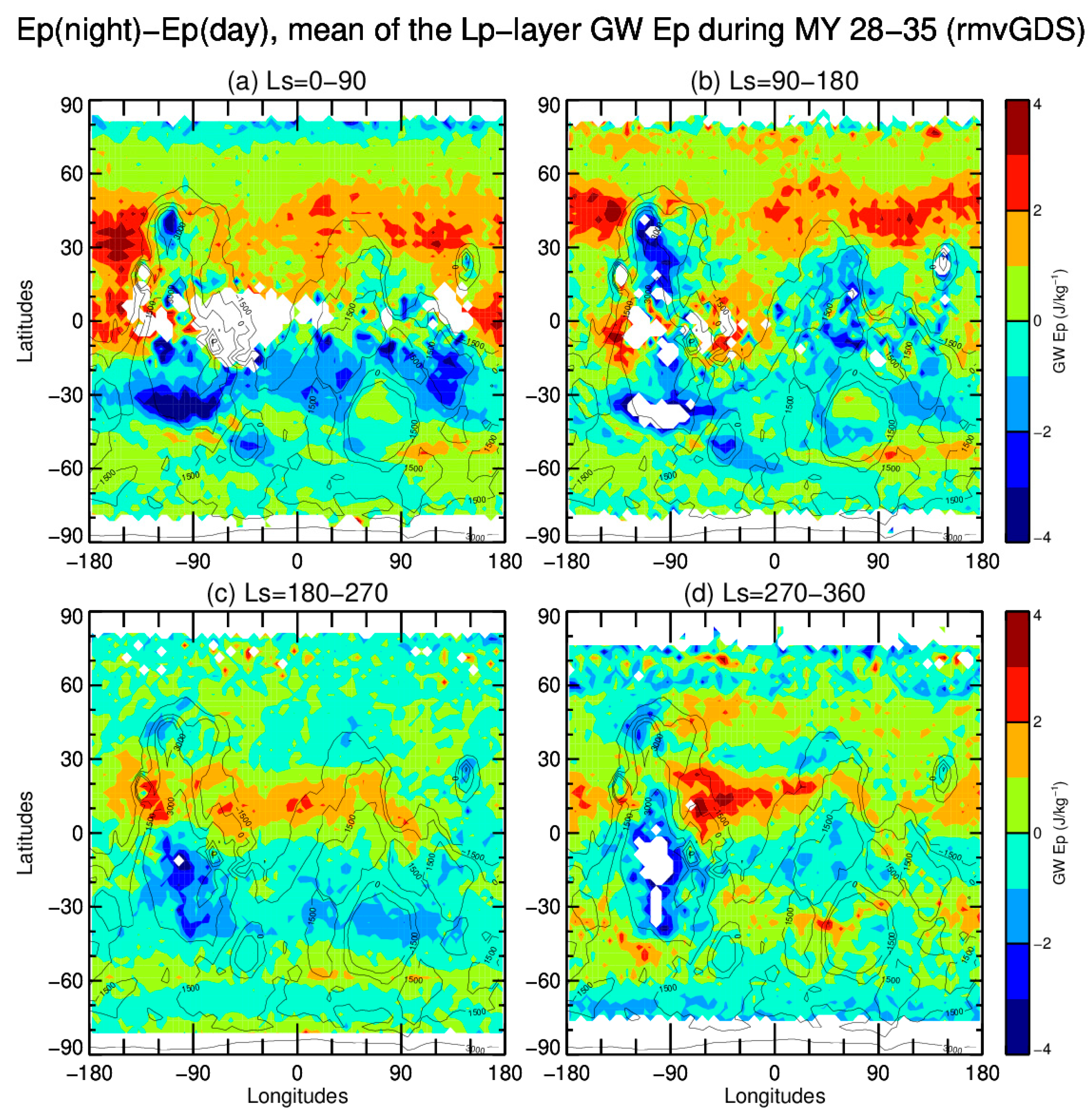

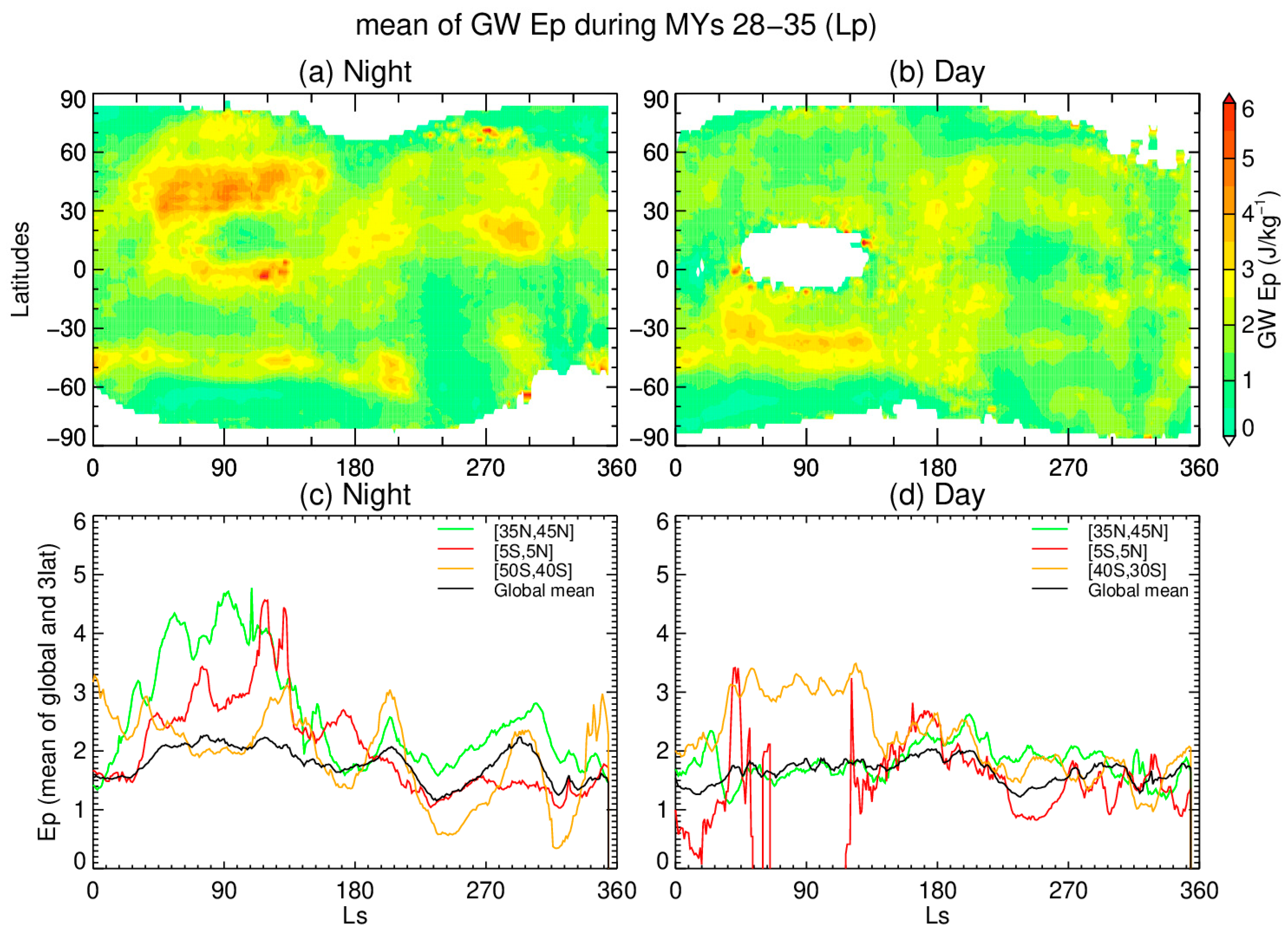

3.1.1. Lp-Layer

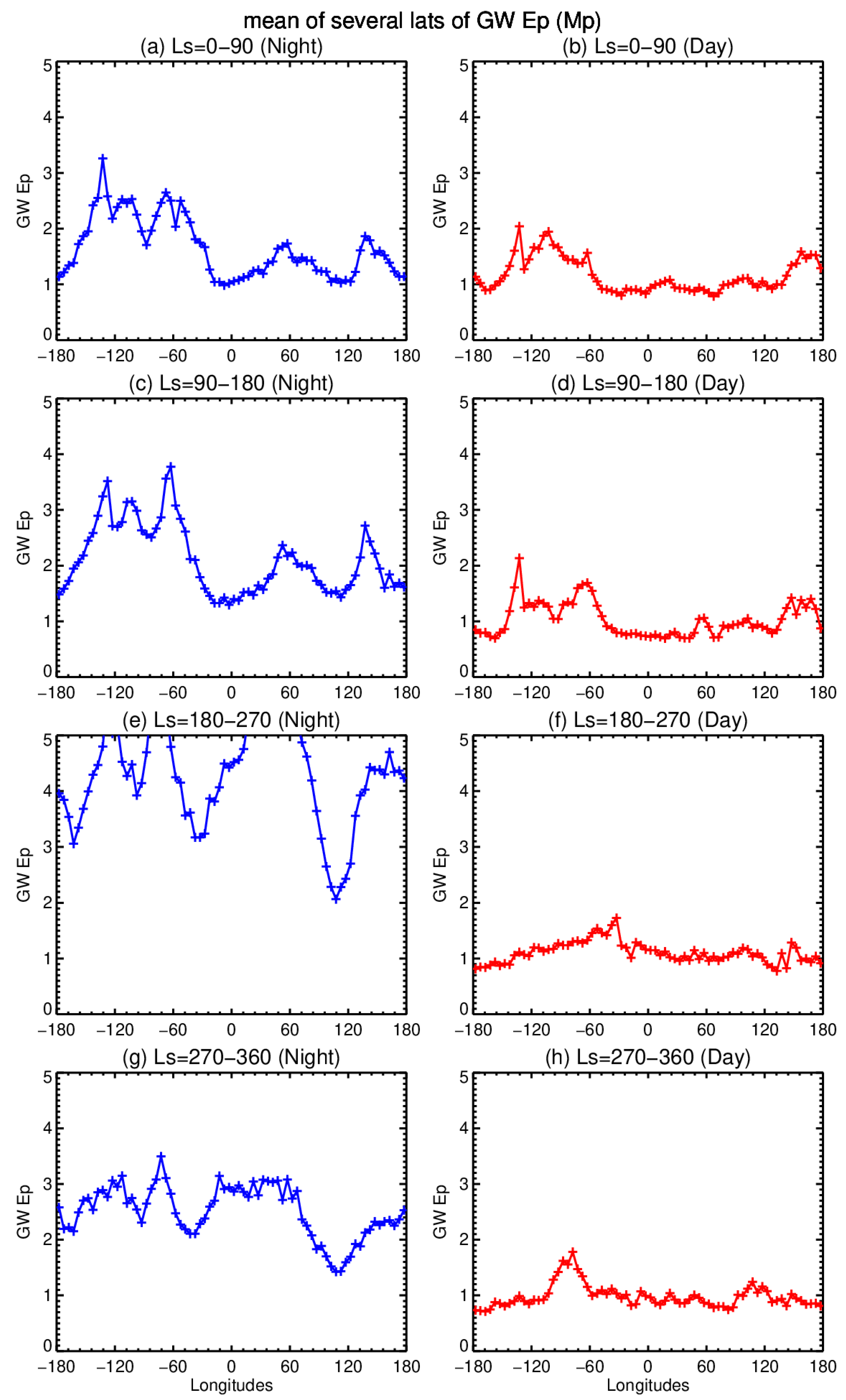

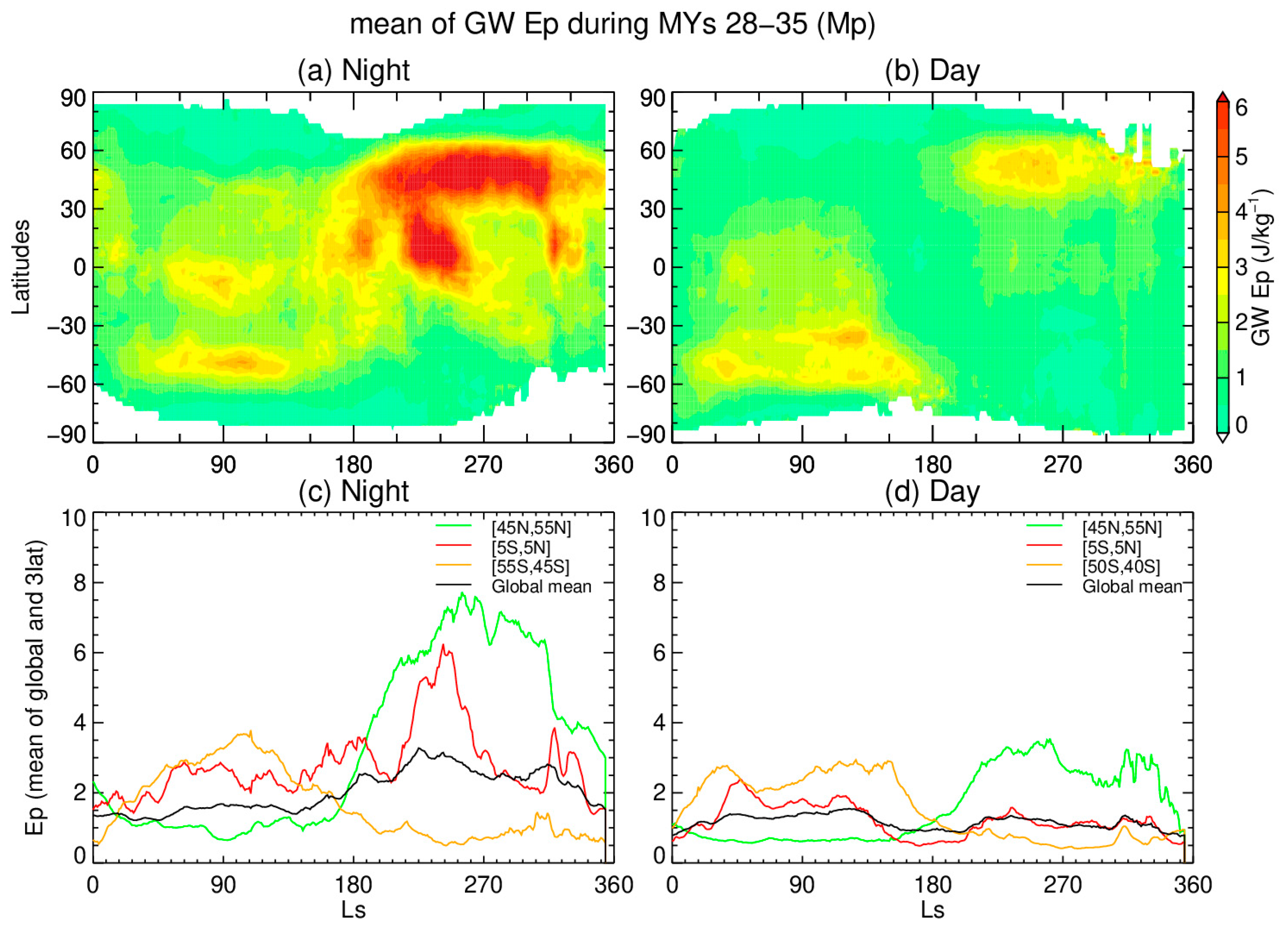

3.1.2. Mp-Layer

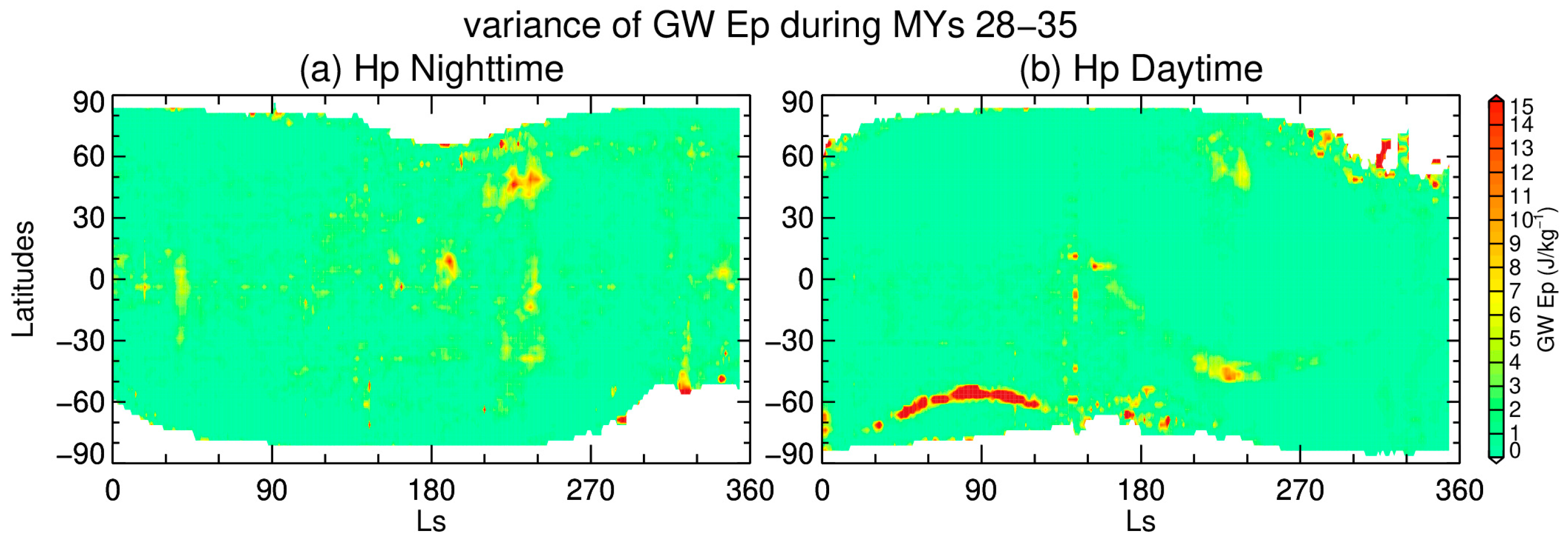

3.1.3. Hp-Layer

3.2. Seasonal Variations in GW Activity

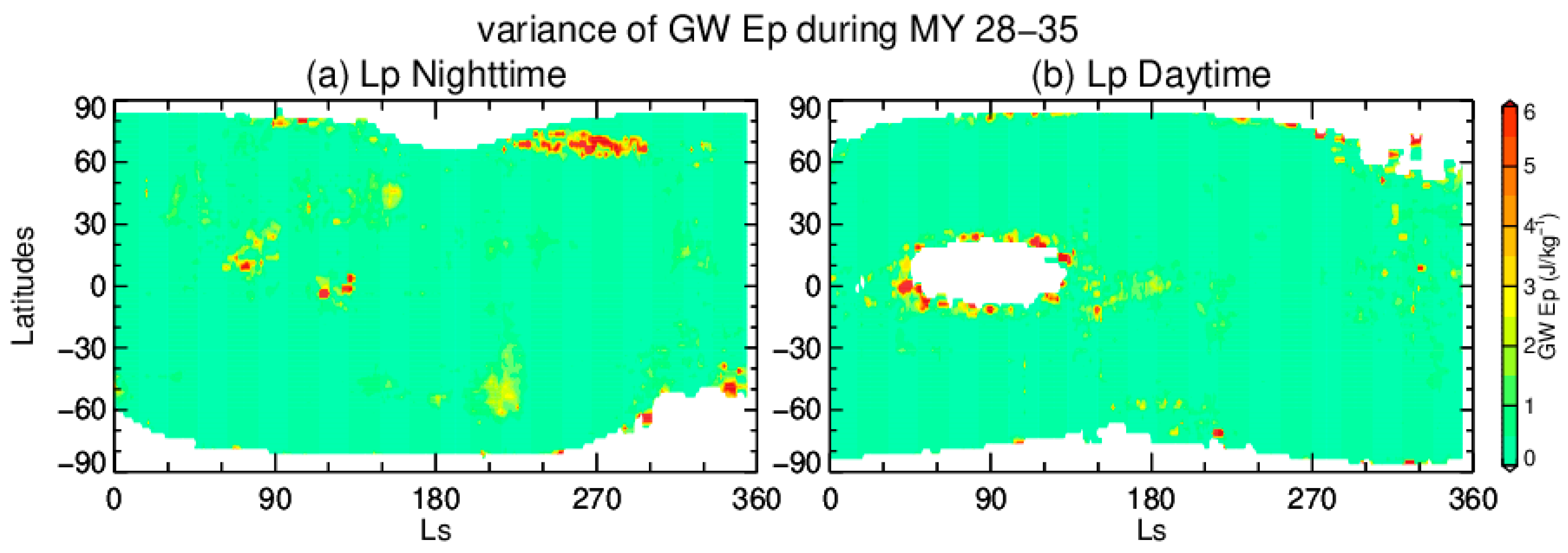

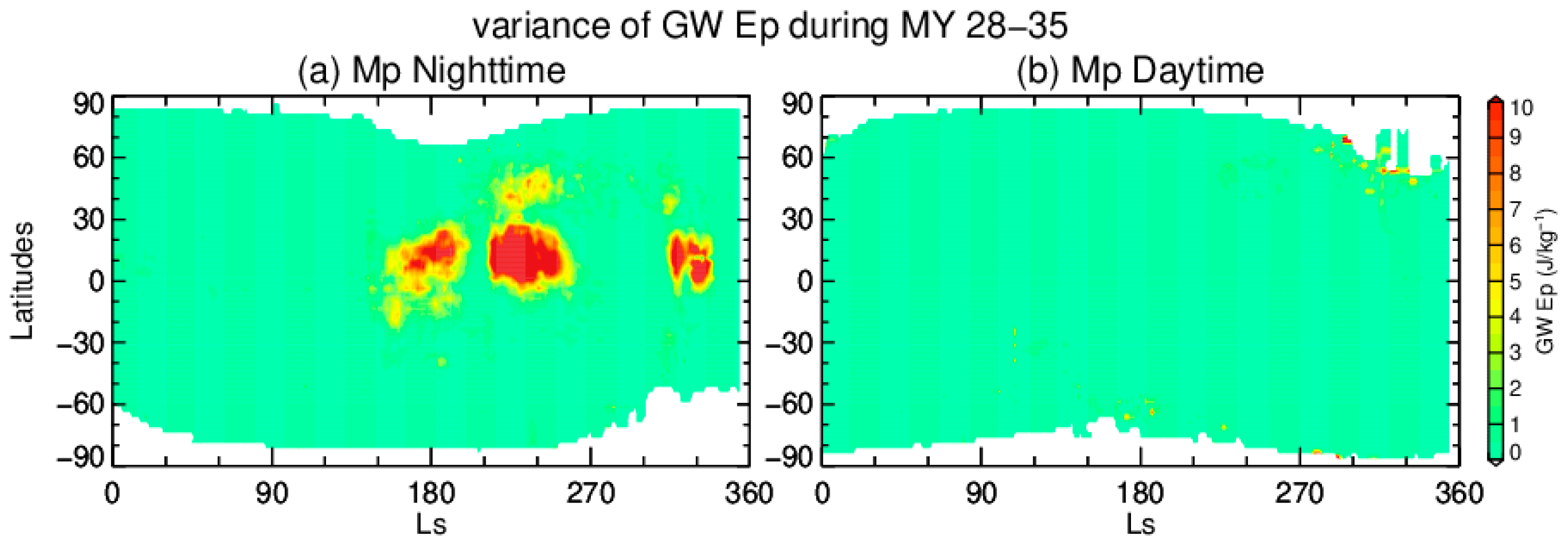

3.3. The Interannual Variability of GWs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Briggs, G.A.; Leovy, C.B. Mariner 9 observations of the Mars north polar hood. J. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1974, 55, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirraglia, J.A. Martian atmospheric Lee waves. Icarus 1976, 27, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.A.; Schofield, J.T.; Seiff, A. Results of the Mars Pathfinder atmospheric structure investigation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 1999, 104, 8943–8955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritts, D.C.; Wang, L.; Tolson, R.H. Mean and gravity wave structures and variability in the Mars upper atmosphere inferred from Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey aerobraking densities. J. Geophys. Res. 2006, 111, A12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ingersoll, A.P. Martian clouds observed by Mars Global Surveyor Mars Orbiter Camera. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2002, 107(E10), 5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, D.P.; Simpson, R.A.; Twicken, J.D.; Tyler, G.L.; Flasar, F.M. Initial results from radio occultation measurements with Mars Global Surveyor. J. Geophys. Res. 1999, 104, 26997–27012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creasey, J.E.; Forbes, J.M.; Hinson, D.P. Global and seasonal distribution of gravity wave activity in Mars’ lower atmosphere derived from MGS radio occultation data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L01803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T.; Medvedev, A.S.; Hartogh, P.; Takahashi, M. On Forcing the Winter Polar Warmings in the Martian Middle Atmosphere during Dust Storms. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan. Ser. II 2009, 87, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; McCleese, D.J.; Schofield, J.T.; Smith, M.D. Interannual similarity in the Martian atmosphere during the dust storm season. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 6111–6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, N.G.; Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Schofield, J.T. A multiannual record of gravity wave activity in Mars’s lower atmosphere from on-planet observations by the Mars Climate Sounder. Icarus 2020, 341, 113630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, T.; Medvedev, A.S.; Yiğit, E. Gravity Wave Activity in the Atmosphere of Mars During the 2018 Global Dust Storm: Simulations With a High-Resolution Model. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2020, 125, e2020JE006556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, E.; Medvedev, A.S.; Benna, M.; Jakosky, B.M. Dust Storm-Enhanced Gravity Wave Activity in the Martian Thermosphere Observed by MAVEN and Implication for Atmospheric Escape. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL092095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, J.; Li, T.; Cui, J. Gravity Waves in Different Atmospheric Layers During Martian Dust Storms. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2022, 127, e2021JE007170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, N.G.; Pankine, A.; Battalio, J.M.; Wright, C.; Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Piqueux, S.; Schofield, J.T. Mars Climate Sounder Observations of Gravity-wave Activity throughout Mars’s Lower Atmosphere. Planet. Sci. J. 2022, 3, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, N.G.; Richardson, M.I.; Lawson, W.G.; Lee, C.; McCleese, D.J.; Kass, D.M.; Kleinböhl, A.; Schofield, J.T.; Abdou, W.A.; Shirley, J.H. Convective instability in the martian middle atmosphere. Icarus 2010, 208, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.L.; Preusse, P.; Eckermann, S.D.; Jiang, J.H.; Juarez, M.d.l.T.; Coy, L.; Wang, D.Y. Remote sounding of atmospheric gravity waves with satellite limb and nadir techniques. Adv. Space Res. 2006, 37, 2269–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.; Zhu, X.; Sheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Climatological Gravity Waves in the Middle and Upper Atmosphere of Mars Based on ACS/TGO Observations. Astrophys. J. 2023, 953, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleese, D.J.; Schofield, J.T.; Taylor, F.W.; Calcutt, S.B.; Foote, M.C.; Kass, D.M.; Leovy, C.B.; Paige, D.A.; Read, P.L.; Zurek, R.W. Mars Climate Sounder: An investigation of thermal and water vapor structure, dust and condensate distributions in the atmosphere, and energy balance of the polar regions. J. Geophys. Res. 2007, 112, E05S06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinböhl, A.; Schofield, J.T.; Kass, D.M.; Abdou, W.A.; Backus, C.R.; Sen, B.; Shirley, J.H.; Lawson, W.G.; Richardson, M.I.; Taylor, F.W.; et al. Mars Climate Sounder limb profile retrieval of atmospheric temperature, pressure, and dust and water ice opacity. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114, E10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberle, R.M.; Clancy, R.T.; Forget, F.; Smith, M.D.; Zurek, R.W. (Eds.) The Atmosphere and Climate of Mars; Cambridge Planetary Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. i–i. [Google Scholar]

- Starichenko, E.D.; Belyaev, D.A.; Medvedev, A.S.; Fedorova, A.A.; Korablev, O.I.; Trokhimovskiy, A.; Yiğit, E.; Alday, J.; Montmessin, F.; Hartogh, P. Gravity Wave Activity in the Martian Atmosphere at Altitudes 20–160 km From ACS/TGO Occultation Measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2021, 126, e2021JE006899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Nishida, M.; Rocken, C.; Ware, R.H. A Global Morphology of Gravity Wave Activity in the Stratosphere Revealed by the GPS Occultation Data (GPS/MET). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000, 105, 7257–7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salby, M.L. Sampling Theory for Asynoptic Satellite Observations. Part I: Space-Time Spectra, Resolution, and Aliasing. J. Atmos. Sci. 1982, 39, 2577–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moudden, Y.; Forbes, J.M. Insight into the seasonal asymmetry of nonmigrating tides on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatain, A.; Spiga, A.; Banfield, D.; Forget, F.; Murdoch, N. Seasonal Variability of the Daytime and Nighttime Atmospheric Turbulence Experienced by InSight on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL095453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, T.; Watanabe, A.; Maejima, Y. Convective generation and vertical propagation of fast gravity waves on Mars: One- and two-dimensional modeling. Icarus 2016, 267, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Yoshiki, M. Gravity Wave Generation around the Polar Vortex in the Stratosphere Revealed by 3-Hourly Radiosonde Observations at Syowa Station. J. Atmos. Sci. 2008, 65, 3719–3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L.J.; Kleinböhl, A.; Kass, D.M. Observations of Ubiquitous Nighttime Temperature Inversions in Mars’ Tropics After Large-Scale Dust Storms. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL092651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Chen, B.; Li, T.; Wu, Z.; Zong, W. Seasonal and Interannual Variation in Martian Gravity Waves at Different Altitudes from the Mars Climate Sounder. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020319

Li J, Chen B, Li T, Wu Z, Zong W. Seasonal and Interannual Variation in Martian Gravity Waves at Different Altitudes from the Mars Climate Sounder. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020319

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Jing, Bo Chen, Tao Li, Zhaopeng Wu, and Weiguo Zong. 2026. "Seasonal and Interannual Variation in Martian Gravity Waves at Different Altitudes from the Mars Climate Sounder" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020319

APA StyleLi, J., Chen, B., Li, T., Wu, Z., & Zong, W. (2026). Seasonal and Interannual Variation in Martian Gravity Waves at Different Altitudes from the Mars Climate Sounder. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020319