1. Introduction

A geostationary Earth orbit (GEO) is a type of geosynchronous orbit with an orbital inclination of 0 degrees, characterized by a stationary sub-satellite point such that its ground track is a single point. GEO orbital targets are situated approximately 35,768 km above the Earth’s equator, synchronized with the Earth’s rotation. This configuration results in a stationary position relative to the Earth, enabling continuous coverage over a vast area. Due to their high application value, GEO targets are extensively utilized across military, civilian, and commercial domains, garnering significant strategic interest worldwide [

1,

2]. If high-resolution imaging of GEO targets can be acquired, information such as the satellite structure, the equipment carrier type and size, etc., can then be obtained, and further analysis of its frequency, imaging ability, and undertaken tasks can be implemented.

Compared to optical imaging, radar imaging has the advantage of imaging capability in all-weather conditions and at all times of the day. In radar imaging, high range resolution is typically achieved through the pulse compression of wideband signals, while cross-range resolution is obtained via the aperture formed by the antenna. Imaging radar can be further categorized into Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) [

3,

4] and Inverse Synthetic Aperture Radar (ISAR) [

1,

5,

6,

7]. SAR primarily relies on the motion of the radar platform to form a synthetic aperture, whereas ISAR mainly utilizes the motion of the target. Additionally, radars can be classified based on the deployment platform, primarily into ground-based and space-based radars [

8]. Due to the constraint of the radar power–aperture product, the signal-to-noise ratio in space-based ISAR imaging systems is relatively low, leading to poor imaging quality. Ground-based radar systems are capable of detecting space targets and performing ISAR imaging with relative motion. A two-dimensional ISAR image represents the projection of the target onto the range-Doppler imaging plane. Consequently, when the imaging plane changes significantly, the two-dimensional ISAR images of the same target can vary considerably. In contrast, three-dimensional (3D) ISAR imaging can extract more comprehensive information such as the spatial structure, size, shape, and motion posture of the target. Based on different imaging principles, 3D ISAR imaging methods can primarily be categorized into two categories: one combines ISAR imaging techniques with interferometric techniques [

9], and the other is based on time sequences of one-dimensional range profiles or two-dimensional ISAR images [

10].

On the other hand, the Ground-Based Synthetic Aperture Radar (GB-SAR) is a SAR system deployed on the Earth’s surface. GB-SAR offers unique advantages such as high precision, continuity, and capability for long-term monitoring [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], making it a core tool in fields like landslide detection, slope stability monitoring, mining area subsidence, and the deformation monitoring of large-scale structures. Reference [

2] first proposed the use of GB-SAR for imaging space targets and analyzed the influence of the imaging aperture on parameters such as azimuth resolution. However, since the observed target is located far from the GEO, a relatively large power-to-aperture product is usually required for observation. Radars meeting this requirement are often too bulky and difficult to move, making it challenging to form a synthetic aperture in practice.

Multiple-Input Multiple-Output (MIMO) radar can form a virtual aperture through different combinations of transmitting and receiving antennas, enabling the imaging of observed targets without requiring physical movement of the antenna array [

16,

17,

18]. Currently, operational radars exist that can detect GEO targets. If multiple such systems were coherently combined to synthesize a very large virtual aperture, this distributed network would gain the capability to generate images of GEO targets.

Frequency division multiplexing (FDM) and time division multiplexing (TDM) are two modes of the MIMO radar. In the FDM mode, all transmitting antennas emit signals simultaneously, but each antenna’s carrier frequency is offset by a small amount, making the signals orthogonal in the frequency domain [

19]. Its advantages include a high data rate, high unambiguous velocity, and efficient utilization of time resources. The drawbacks, however, lie in the complexity of waveform design and processing, high hardware requirements, and the difficulty of direct adaptation based on existing hardware. In TDM mode, multiple transmitting antennas operate sequentially in different time slots [

20]. At any given moment, only one transmitting antenna is active, and all receiving antennas capture echoes solely from that specific transmitter. Since the signals are separated in time, they are inherently orthogonal. The TDM mode offers several advantages: it avoids complex waveform design, enjoys low hardware complexity, and can be implemented by upgrading existing hardware with synchronization commands for time, phase, and spatial alignment.

For relatively stationary targets like those in the GEO, the target can be considered motionless during a short time period. The TDM mode can meet the time resolution requirements. Therefore, to maximize the utilization of the power and frequency resources of each radar, the sequential transmitting and simultaneously receiving MIMO mode is a reasonable choice.

Similarly to Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imaging algorithms, MIMO radar imaging algorithms can also be classified into frequency-domain techniques and time-domain techniques. Xiaodong Zhuge first applied the three-dimensional Range Migration Algorithm (RMA) to near-field MIMO radar imaging. By combining the transmitting wave vector and receiving wave vector, a complete target spatial spectrum was obtained, achieving high-quality imaging results [

21]. However, the topology of the MIMO radar must satisfy specific conditions for the RMA to be used effectively in imaging [

18,

22].

The back-projection (BP) imaging algorithm utilizes the delay-and-sum principle to achieve the focusing process. It is adaptable to arbitrary array topologies, easily extendable to three dimensions, and its application is not limited by near-field or far-field conditions, leading to its widespread use in near-field MIMO radar imaging. Frank Gumbmann combined the MIMO array design with digital beamforming technology [

23], investigating the application of millimeter-wave 3D imaging in Non-Destructive Testing. Xiaodong Zhuge designed an ultra-wideband 3D imaging system based on MIMO-SAR for concealed weapon detection [

24]. By integrating the characteristics of ultra-wideband signals with sparse array design techniques, this approach can reduce the number of array elements while suppressing grating lobe levels. The pixel-by-pixel coherent processing in BP imaging incurs a substantial computational burden. This high computational cost hinders its application in scenarios requiring high real-time performance.

Currently, some fast BP algorithms, such as Fast Back-Projection (FBP) and Fast Factorized Back-Projection (FFBP) [

25], are attracting increasing attention from researchers. To suppress grating and sidelobes in back-projection imaging, several aperture-domain suppression algorithms have been proposed, such as the Coherence Factor (CF) [

26,

27], Phase Coherence Factor (PCF), and aperture cross-correlation, which have proven to be effective in suppressing these undesired components. CF is defined as the ratio of the coherent power sum to the non-coherent power sum in the aperture domain data. At the main lobe, the amplitudes of the coherent and non-coherent sums are similar, so the CF value is close to 1; whereas grating/sidelobes have a lower coherence, making the coherent power sum less than the non-coherent power sum, thus resulting in CF values less than 1. The basic idea of the PCF algorithm is that the phase distribution in the aperture domain data is consistent at the main lobe but relatively disordered at the grating/sidelobes.

This paper proposes a novel ground-based distributed MIMO radar imaging paradigm to overcome the challenge that conventional radar cannot image stationary GEO targets due to the lack of relative motion. Specifically, a “sequential transmission, simultaneous reception” operational mode is adopted to achieve high-resolution, three-dimensional imaging through global networking.

The core contributions of this work are as follows: 1. Scenario Definition and Modeling: This study is the first to systematically define the “ground-based distributed MIMO radar GEO imaging” scenario. Based on the constraints imposed by the Earth’s curvature, the observable range is derived, quantifying the theoretical performance bounds of the system. 2. Imaging Framework Construction: A dedicated Three-Dimensional Target-Oriented (TDTO) coordinate system is established to uniformly describe the geometric relationships among globally distributed radars, the target, and the Earth. Combined with the back-projection (BP) algorithm, a complete processing chain is formed. 3. Feasibility Verification: Through systematic experiments ranging from point targets to full-wave satellite simulations, this work provides numerical validation of the theoretical feasibility of achieving 0.1 m resolution three-dimensional imaging.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the ground-based MIMO radar imaging scenario for GEO targets and then analyzes the azimuth resolution.

Section 3 establishes a Three-Dimensional Target-Oriented coordinate system for the ground-based radar imaging of GEO targets, and the BP imaging algorithm is used to image the target.

Section 4 presents the simulation results and analysis, including point targets and satellite models. Beyond validating the ideal imaging performance, this section further investigates the influence of key system parameters (e.g., baseline length and element spacing) on imaging quality and evaluates the system’s sensitivity to practical non-idealities such as synchronization errors and ionospheric effects. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. Azimuth Resolution of GEO Targets

Figure 1 depicts an imaging scenario involving a ground-based radar and a GEO satellite target. P is a point target on the geostationary orbit, and the red line indicates the transmission path of the electromagnetic wave from the transmitting antenna to target P, while the blue line indicates the path of the electromagnetic wave scattered from target P back to the receiving antenna of the GB radar. Assuming that the Earth is an ideal sphere, a cross-sectional view passing through the Earth’s center, the North Pole, and target P is depicted in

Figure 2.

In

Figure 2, the center of the sphere is denoted as O, and P is the GEO target. The line connecting O and P intersects with the Earth’s surface at point Q. In this 2D plane, the two tangents to the Earth drawn from target P contact the Earth at points T1 and T2, respectively. Therefore, the observable arc on the Earth’s surface for target P is defined as the segment T1-Q-T2. The distance OQ is equal to the Earth’s radius, while the distance OP equals the sum of the Earth’s radius and the geostationary orbit altitude. Based on this geometry, the angle T

1PO, denoted as

in

Figure 2, can be expressed as

The value of is calculated to be 8.696°; therefore, the angle is 81.304°. This indicates that the maximum observable range for GEO targets from the Earth’s surface is (−81.304°, 81.304°). Due to this geometric symmetry, the observation angle for radars distributed along the latitudinal direction (equator) is also constrained. Taking the target’s sub-satellite point as the center, the maximum observable range along the equatorial plane is also (−81.304°, 81.304°).

However, due to the elevation angle constraints of the radar, it is impossible for the radar to be deployed near point T

1. Suppose one end of the radar array is located at S

1, and S

1 is an arbitrary point on the arc segment Q-T

1, as depicted in

Figure 3. In the triangle PS

1O, the relationship between angles

and

can be derived using the Law of Sines and the Law of Cosines as follows.

With angle

known, the length of side PS

1 can be obtained using the Law of Cosines.

Among these, the length of

is the Earth’s radius. Then, according to the Law of Sines,

Then, the angle can be calculated using Equation (3).

With angle

known, then, according to the Law of Sines

Then, the angle can be calculated using Equation (4).

Following the determination of the ground baseline-to-target observation angles, the corresponding imaging range and azimuth resolution are derived and presented below.

The range resolution of the MIMO radar is determined by the bandwidth of the transmitting signal and is expressed as

where

denotes the signal bandwidth in frequency;

is the speed of light in free space. In the case of a rectangular window function, the theoretical resolution derived above must be scaled by a factor of 0.886. Equation (5) clearly demonstrates an inverse proportionality between range resolution and signal bandwidth in frequency. Specifically, an increase in signal bandwidth causes a corresponding decrease in range resolution values, thereby enhancing the range resolution capability of the system.

According to Reference [

2], the azimuth resolution in SAR imaging is given by

where

represents the observation angle formed by the synthetic aperture with respect to the target, and

is the longitudinal angular difference between the target’s sub-satellite point and the array.

For MIMO arrays, the boundary between the near-field and far-field is defined as the range where the maximum two-way path difference between the target and the array center versus the array edges is less than

[

28]. Ground-based radar imaging of GEO targets operates in the near-field regime. And the PCA (phase center approximation) method, which assumes far-field conditions, does not apply for analyzing the performance of such MIMO arrays. Therefore, we conduct the analysis from the perspective of wavenumber support. This method is applicable to the near-field resolution analysis of SAR and MIMO arrays.

Take two-dimensional imaging as an example. In

Figure 4, the reference line is a straight line perpendicular to line OP in

Figure 3. At any given point on Earth, the observation angle relative to the GEO target is defined as the angle between the local line of sight to the target and a defined reference direction. Assume the number of array elements is N, and the transmitted signal is a stepped-frequency signal

, where

. The angle between the target and the

n-th antenna element is

, where

. According to the two-way echo characteristics of SAR, the spatial spectrum of the target can be obtained as follows:

In SAR, the spatial spectrum of the target exhibits an annular “arc-segment” shape, with an inner arc radius of and an outer arc radius of .

In MIMO arrays, the spatial wavenumber vector of the target is composed of the sum of the transmitting and receiving wavenumber vectors. That is, the two-dimensional spatial spectrum of the MIMO array target is expressed as

Here,

is the angle between the line connecting the target and the n-th transmitting antenna and the reference line, and

is the angle between the line connecting the target and the m-th receiving antenna and the reference line. The spatial spectrum of the MIMO array can be regarded as a combination of M (number of transmitting antennas) spatial spectra, expressed as

Different MIMO array configurations exhibit significant variations in the spatial spectrum shape of a target. To facilitate the analysis, the Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration is taken as an example. As shown in

Figure 5, two transmitting antennas are located at both ends of the antenna array, while

N receiving antennas are situated in the middle of the array, remarked as Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving. It can be observed that the spatial spectrum consists of two parts with a gap between them. To achieve better imaging performance, the gap between the two spatial spectrum segments can be eliminated through array design. The ideal array design should ensure that the spatial spectrum segments neither overlap nor have gaps. Generally, under near-field conditions, a MIMO array cannot guarantee non-overlapping spatial spectra for targets at all positions.

If only a single transmitter in the array is employed, and the scattered signal is received by

N receiving antennas, the array is remarked as One-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving. The corresponding spatial spectrum for this configuration is illustrated in

Figure 6.

After obtaining the spatial spectral support region of the target, the imaging resolution can be analyzed. The spatial spectral support region determines the imaging resolution of the target. Generally, a larger spatial spectral support region results in a higher imaging resolution.

According to the Rayleigh criterion [

29], the following relationship is obtained:

By selecting the center frequency and combining Equation (8) with Equation (9), the imaging resolution in SAR mode can be derived:

where

is the azimuth resolution in SAR mode, and

is the range resolution in SAR mode.

The imaging resolution in MIMO mode is given by

where

is the azimuth resolution in MIMO mode, and

is the range resolution in MIMO mode.

In practice, the above expression must be multiplied by the corresponding window function factor.

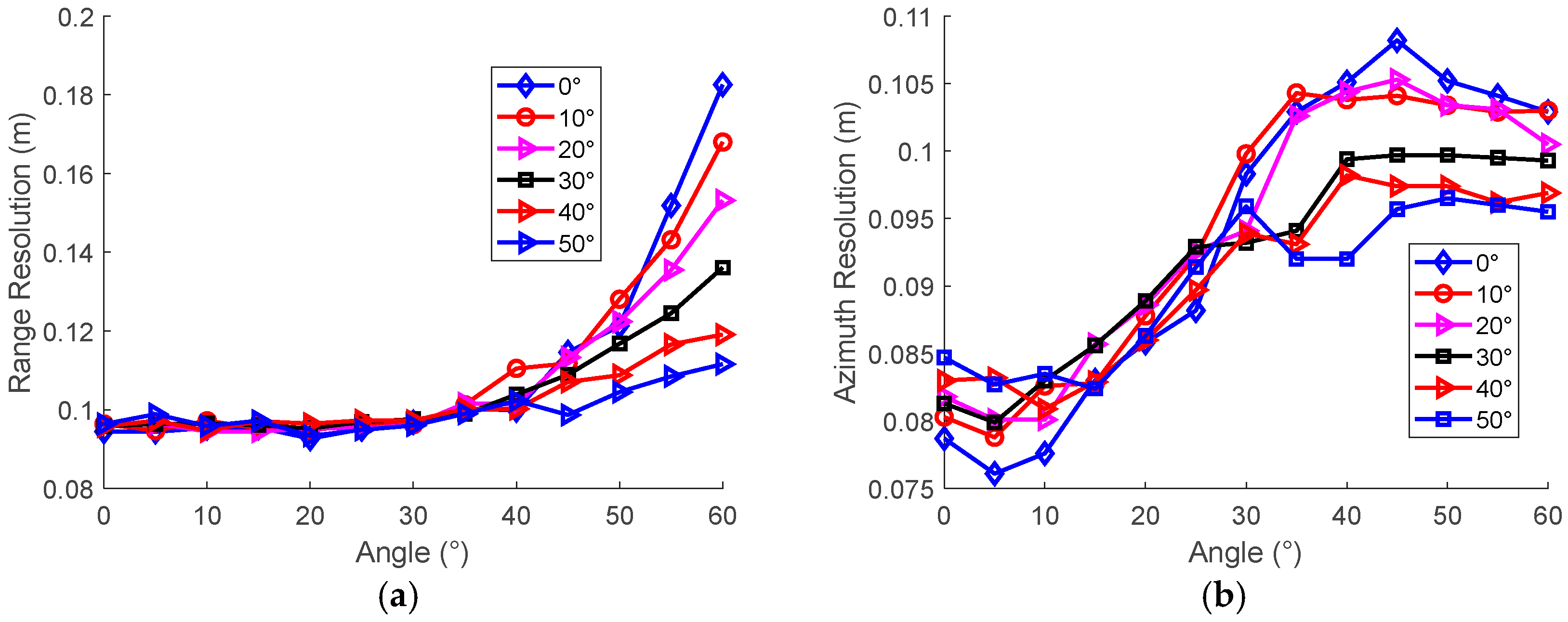

Assuming a point target is located at P in

Figure 1, the relationship between the theoretical target resolution and the ground baseline length for the Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving and One-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configurations are shown in

Figure 7. For the Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration, the two transmitting antennas are positioned at the ends of the array. Consequently, the baseline length is defined as the distance between these two transmitting antennas. For the One-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration, the transmitting antenna is fixed at a single location. Here, the baseline length refers to the ground baseline length of the receiving antenna array.

In

Figure 7, the value of the theoretical azimuth resolution decreases as the baseline length increases from 800 km to 4000 km. For the Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration, when the transmitting signal center frequency is 10 GHz, the theoretical resolution corresponding to baseline length of 1000 km, 2000 km, and 3000 km is 0.47 m, 0.24 m, and 0.16 m, respectively. When the center frequency is 15 GHz, the azimuth resolution corresponding to same baseline length is 0.32 m, 0.16 m, and 0.11 m, respectively. When the center frequency is 35 GHz, the corresponding resolution further improves to 0.14 m, 0.07 m, and 0.05 m, respectively.

For the One-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration, the absence of half the wavenumber support results in a degraded resolution under identical aperture lengths. Specifically, when the center frequency is 10 GHz, the theoretical resolution corresponding to three baseline lengths is 0.95 m, 0.48 m, and 0.32 m, respectively. When the center frequency is 15 GHz, the theoretical resolution is 0.63 m, 0.32 m, and 0.21 m, respectively. When the center frequency is 35 GHz, the theoretical resolution is 0.27 m, 0.14 m, and 0.09 m, respectively.

The impact on the azimuth resolution of angle

is analyzed. For the One-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array configuration, when the center frequency is 35 GHz, and the baseline length is 1500 km, the theoretical azimuth varies with angel

, as depicted in

Figure 8. The azimuth resolution degrades as

increases from 0° to 70°.

Note that the theoretical resolution values in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 do not account for azimuth windowing or processing techniques such as CF weighting. The above analysis demonstrates that, when the center frequency is 35 GHz and baseline length is 2000 km, the Ends-Transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array’s theoretical azimuth resolution is 0.07 m, while the One-transmitting and Multiple-Receiving array is 0.14 m. These results confirm the theoretical feasibility of imaging GEO targets using ground-based MIMO radar.

Figure 9 shows a cross-sectional view of the equatorial plane, where O represents the Earth’s center (and also the center of the geostationary orbit). Point A lies on the Earth’s surface. The lines tangent from A to the Earth intersect the geostationary orbit at points B and C, respectively. The arc BC corresponds to the spatial coverage observable by a radar located at A. With OA equal to the Earth’s radius and OB equal to the geostationary orbital radius, the central angle ∠BOC is calculated as

= 162.608°, which defines the spatial coverage from point A.

If a linear array is deployed along the equator with endpoints A and D, the tangent lines from D intersect the orbit at points E and F. The combined spatial coverage of the array is the intersection of individual coverages, i.e., arc EC. Let the angular extent of the array baseline relative to the Earth’s center be ; then, the observable angular range is . For a baseline length of 1500 km, the resulting spatial coverage is calculated as 149.1793°.

When the radar is not located on the equator, suppose its latitude is

. The tangent plane through this point intersects the equatorial plane along a line at a distance of

from O. The spatial coverage can be computed similarly.

Figure 10 illustrates the spatial coverage of a single radar at different latitudes.

As shown in

Figure 10, even at high latitudes (e.g., =60°), the spatial coverage remains large (144.5123°). The intersection of coverage areas from all antennas in an array still yields a substantial observable range.

3. Three-Dimensional Imaging of GEO Targets

For the three-dimensional imaging of GEO targets, coordinate system synchronization is essential for ensuring geometric accuracy. The Earth-Centered, Earth-Fixed (ECEF) [

30,

31] coordinate system provides an effective synchronization framework that unifies the coordinate representations of geostationary targets, target scattering point models, and ground-based radar arrays, ensuring all entities are modeled within a consistent spatiotemporal reference. The ECEF system originates at the Earth’s center of mass, with its X-axis pointing toward the intersection of the prime meridian and the equator, the Y-axis lying in the equatorial plane perpendicular to the X-axis and directed toward the 90° east longitude, and the Z-axis orthogonal to the equatorial plane, pointing toward the North Pole.

However, in the ECEF coordinate system, when the longitude of a GEO target’s sub-satellite point significantly deviates from 0°, the imaging area of the target is also far from the X-axis. Using the ECEF system as the imaging coordinate system directly would cause variations in the azimuth and range directions, leading to perspective distortion in the imagery and complicating the interpretation of results.

To obtain a front-view 3D image of the target, we establish a Three-Dimensional Target-Oriented coordinate system (TDTO). Its X-axis is defined by the vector from the Earth’s center to the target, the XY-plane coincides with the equatorial plane, the Z-axis is perpendicular to the XY-plane pointing toward the North Pole, and the Y-axis lies in the equatorial plane perpendicular to the X-axis, forming a right-handed system. The established TDTO coordinate system is depicted in

Figure 11.

Figure 11 depicted the TDTO coordinate system for the MIMO radar imaging of GEO targets. This unified coordinate system establishes an accurate geometric foundation for subsequent radar echo modeling. Its relationship to the ECEF coordinate system is defined as follows: the origin and Z-axis orientation remain unchanged, while the XY-plane is rotated by a specific angle about the Z-axis.

The coordinates of ground-based radar are generally expressed in terms of longitude, latitude, and height coordinates. These parameters can be converted to ECEF coordinates through the WGS84 ellipsoid model, with specific conversion methods detailed in Reference [

31]. After converting radar coordinates into the ECEF coordinate system, the subsequent step involves transforming both the radar and GEO target coordinates from the ECEF coordinate system to the TDTO coordinate system.

Assuming the coordinates of point P in the ECEF coordinate system is (x′, y′, z′), then its coordinates (x, y, z) in the TDTO coordinate system satisfy the following rotational relationship:

When the target’s sub-satellite point longitude is

(east longitude), the rotation angle of the ECEF coordinate system relative to the TDTO coordinate system is

, and the corresponding rotation matrix

is given by

The rotation matrix R is utilized to convert the coordinates of all transmitting and receiving antennas in the MIMO radar distributed across the Earth’s surface into the TDTO coordinate system.

In the TDTO coordinate system, the range direction of the target imaging is defined along the X-axis, the azimuth direction is along the Y-axis, and the height direction is along the Z-axis.

During the transmitting and receiving time of ground-based MIMO radar, the target is assumed to be stationary, meaning its coordinate position remains unchanged. The coordinate of the m-th transmitting antenna is denoted as , where the subscript indicates the transmitting antenna, the subscript m is the index of the antenna , and is the total number of transmitting antennas. The coordinate of the n-th receiving antenna is denoted as , where the subscript R indicates the receiving antenna, the subscript n is the index of the antenna , and is the total number of receiving antennas. represents the coordinates of a specific scattering point P on the GEO target.

The distance from the m-th transmitting antenna to point

P can be expressed as

The distance from point

P to the

n-th receiving antenna can be expressed as

The transmitting antenna sequentially emits radar signals, while all receiving antennas synchronously capture scattered signals from the target.

The linear frequency-modulated (LFM) waveform transmitted by the ground-based radar is expressed as

where

is the rectangular window function,

represents the fast time,

denotes the pulse width,

is the imaginary unit,

corresponds to the center frequency, and

indicates the chirp rate.

Given that the target position is known a priori, the radar antenna main beam can be pre-pointed toward the target, satisfying the spatial synchronization condition. Assuming that all radars share identical parameters, minor frequency discrepancies and jitter among their frequency sources are negligible, thereby meeting the frequency synchronization requirement. Each radar employs satellite-based time synchronization to achieve temporal alignment. Disregarding antenna modulation effects, when the m-th transmitting antenna emits a signal, the echo signal from point

P received by the n-th receiving antenna is expressed as

Here, denotes the backscattering coefficient of the point; represents the two-way echo delay of the point.

Equation (18) corresponds to the echo from point

P. Since the radar illumination area covers the entire target, the total target echo constitutes the superposition of echoes from all scattering points within this region. Therefore, the received echo can be expressed as

where

denotes the area illuminated by the radar electromagnetic wave, and

represents the backscattering coefficient of scattering point

.

Assuming dechirp processing is employed for pulse compression, where the transmitted signal serves as the reference signal, the received echo undergoes sequential processing including dechirp, video phase compensation, and inverse Fourier transform. Finally, the one-dimensional range profile of the target is obtained and denoted as .

Based on the back-projection (BP) imaging theory, the imaging area is discretized into grids in the TDTO coordinate system. The numbers of grids along the X-axes, Y-axes, and Z-axes are defined as , , and , respectively, resulting in a total of grids, where each grid corresponds to a single pixel.

The imaging is processed sequentially by the transmitting antenna. When the m-th antenna transmits, the one-dimensional range profiles

from

receiving antennas are coherently summed with appropriate time delays, thereby obtaining the back-projection result

under this specific transmitting antenna:

For each of the

transmitting antennas in sequence, the back-projection result from

N receiving antennas is computed. The final value

at pixel

is the coherent sum of these

individual results.

To further suppress sidelobes and noise in the imaging results, a weighting coefficient is introduced, and the above expression is modified as follows:

where

represents the CF weighting value at pixel point

for the scenario, with M transmitting antennas operating sequentially and

N receiving antennas operating simultaneously, given by

The imaging result at each location is obtained by iterating through every position within the imaging grid. The final output is a three-dimensional matrix, whose dimensions are , and , respectively.