Impacts of Climate Change, Human Activities, and Their Interactions on China’s Gross Primary Productivity

Highlights

- Gross primary productivity (GPP) exhibited a significant upward trend nationwide, especially in deciduous broadleaf forests, croplands, grasslands and savannas.

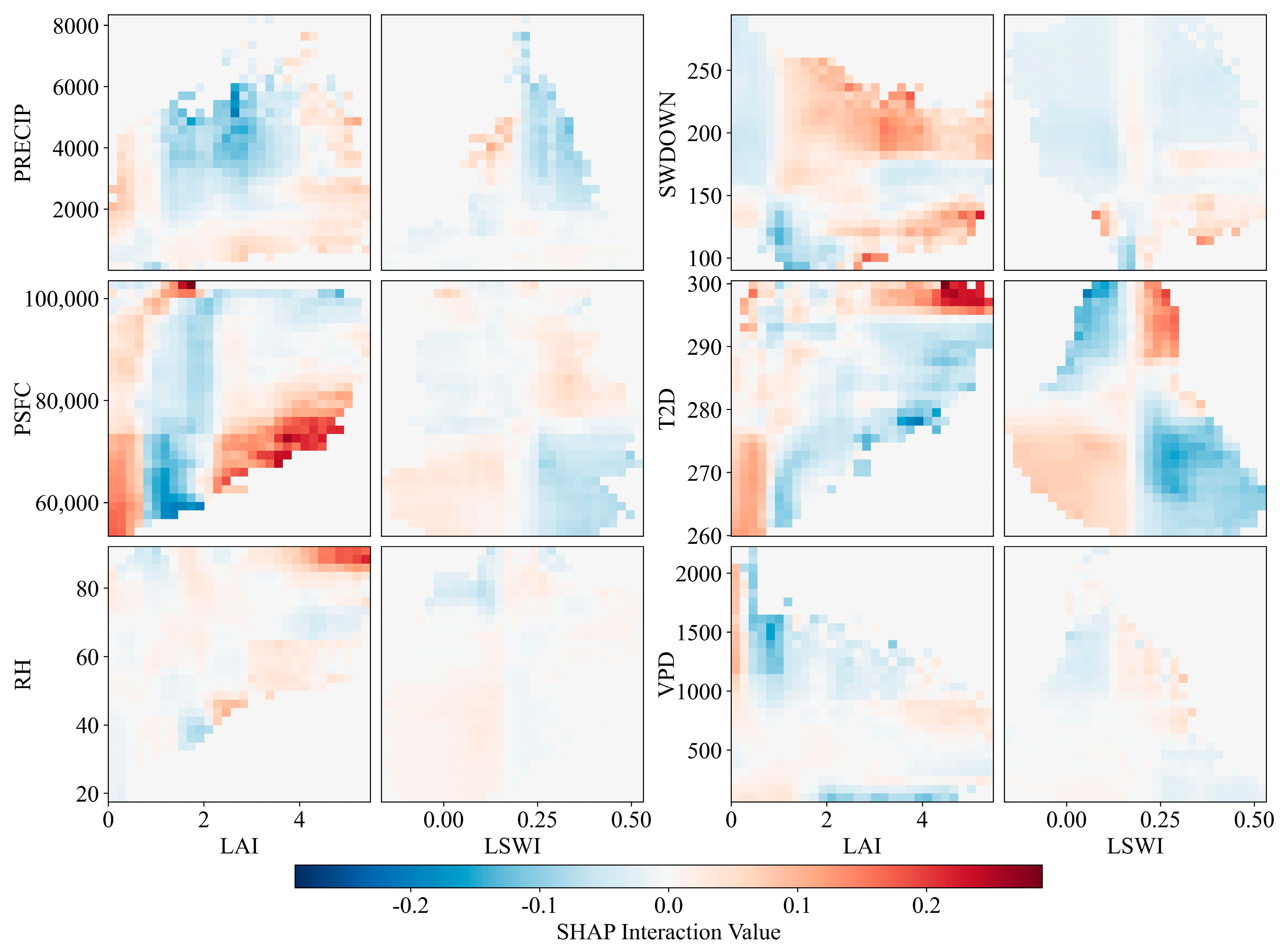

- The SHAP−based analysis revealed Leaf area index (LAI) as the strongest positive driver, while nonlinear interactions with radiation, temperature, and water availability jointly regulate GPP.

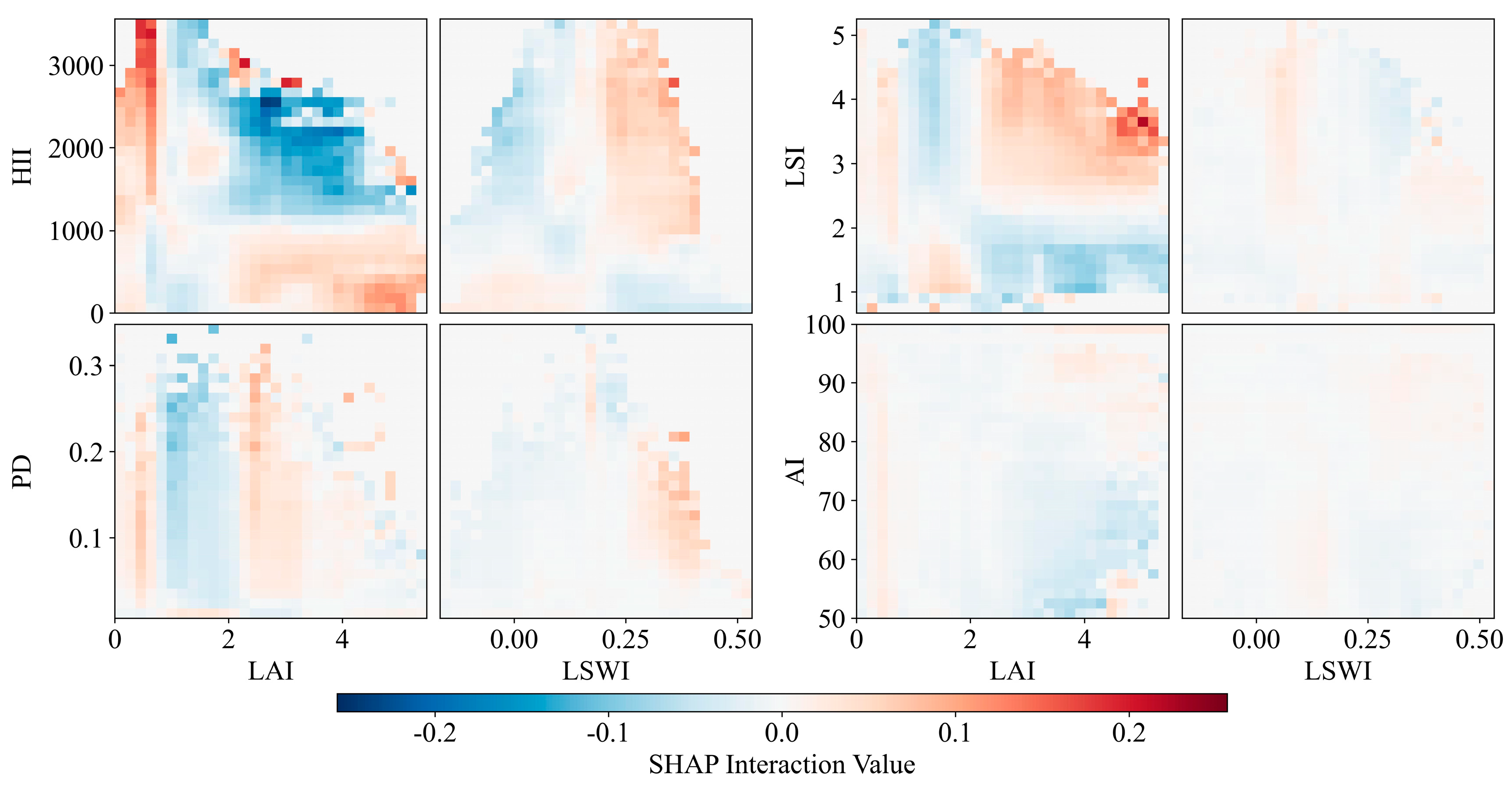

- GPP variations in China are controlled by ecosystem-specific interactions among vegetation, climate, topography, and human activities, indicating that a uniform management or restoration strategy is ineffective across ecosystems.

- The identified dominant drivers suggest targeted ecosystem management strategies: forest management should consider and maintain the interactions between climate and vegetation structure; grassland restoration should prioritize topographic constraints; and cropland productivity should depend strongly on management practices.

- Incorporating these nonlinear and ecosystem-dependent interactions into carbon cycle models can improve projections of ecosystem productivity under climate change, thereby supporting climate adaptation planning and ecosystem protection strategies.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

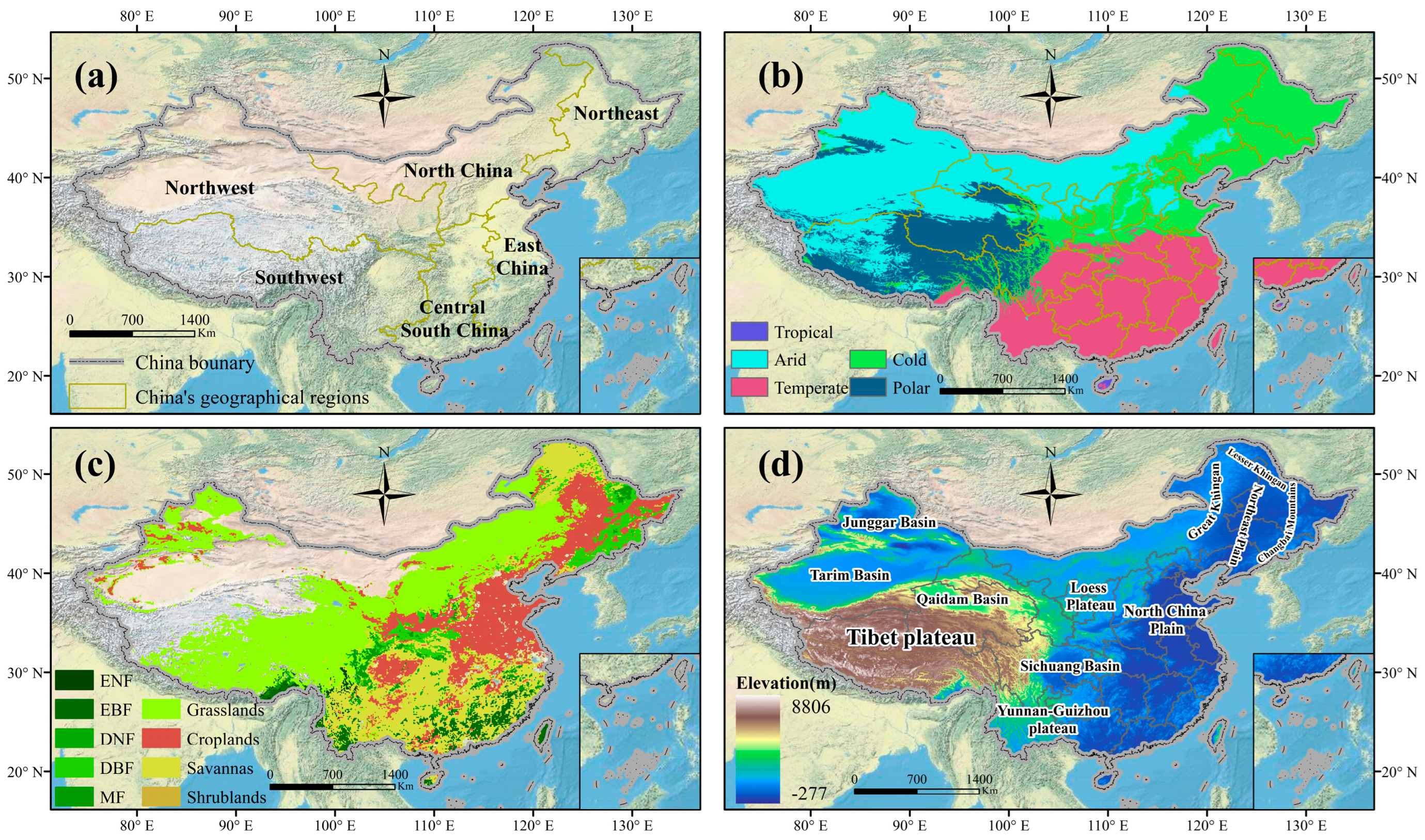

2.1. Study Domain

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. PML−V2 (China) GPP Dataset

2.2.2. MODIS Land Cover and MODIS−Derived LSWI

2.2.3. CMFD Meteorological Dataset

2.2.4. GLASS LAI Dataset

2.2.5. SRTM DEM Dataset

2.2.6. Human Activity Factors

2.2.7. Spatial Harmonization of Datasets

2.3. Mann–Kendall Trend Analysis

2.4. XGBoost Algorithm and SHapley Additive exPlanations

3. Results

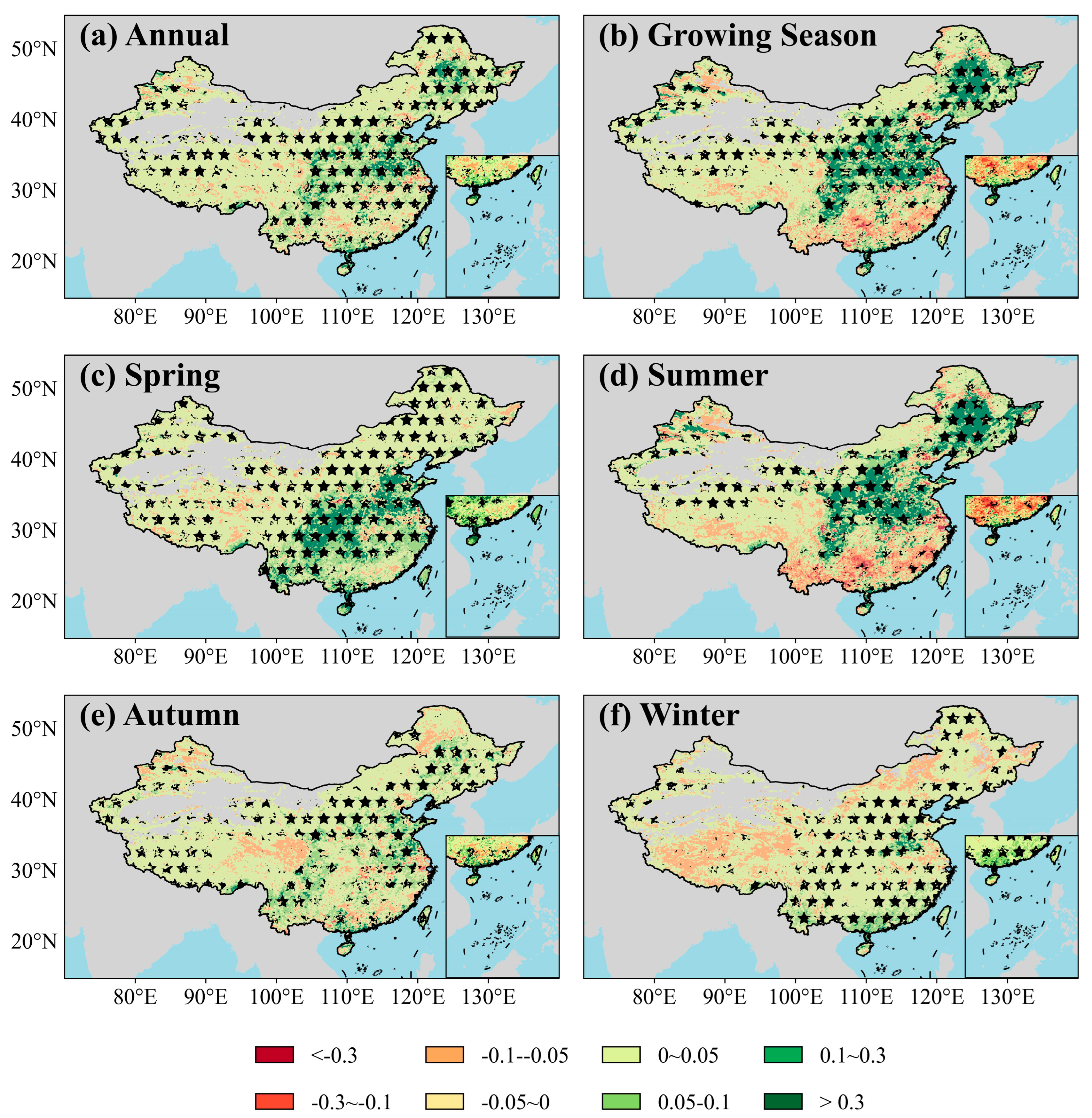

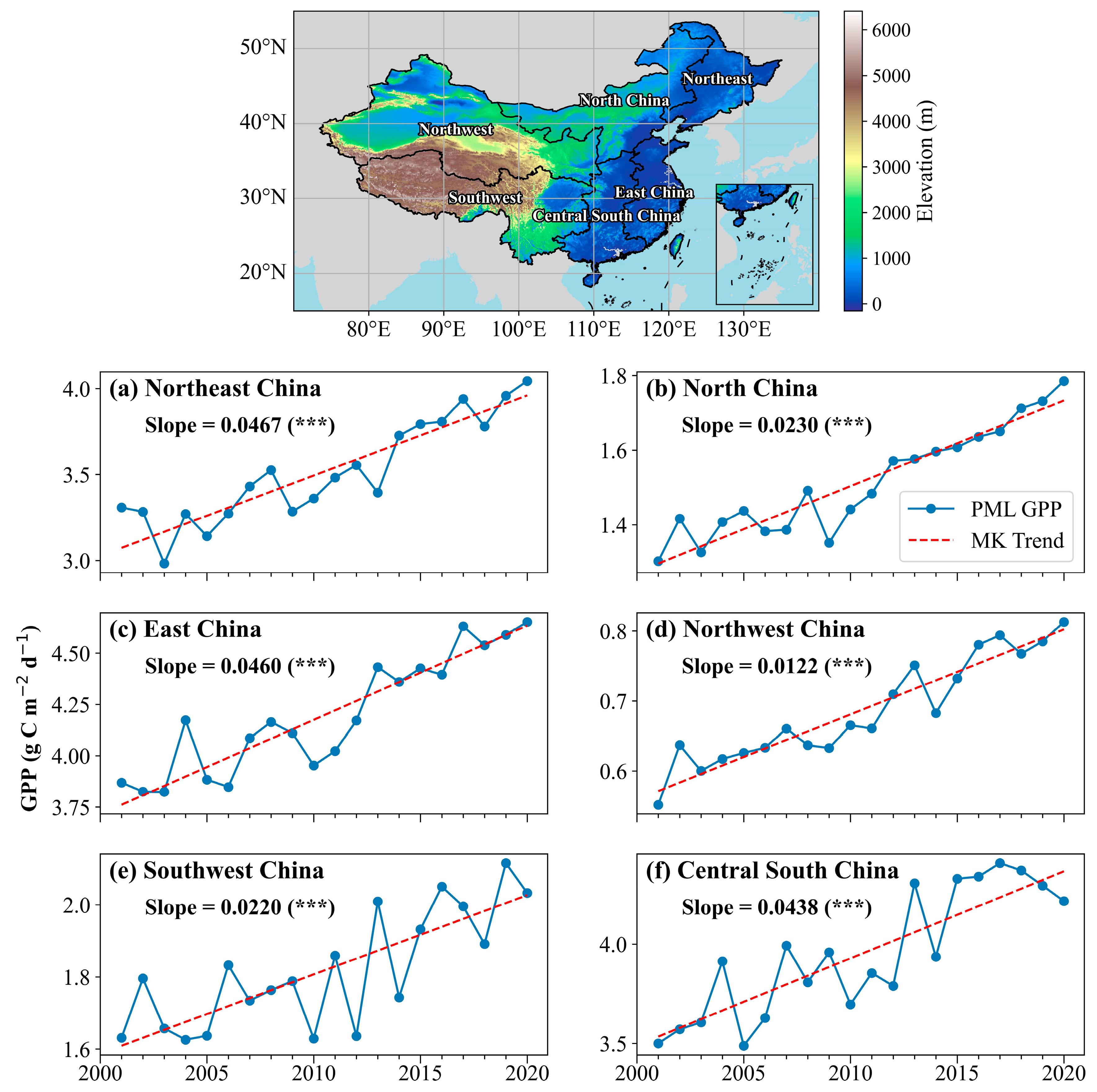

3.1. Spatio−Temporal Trends of GPP over China

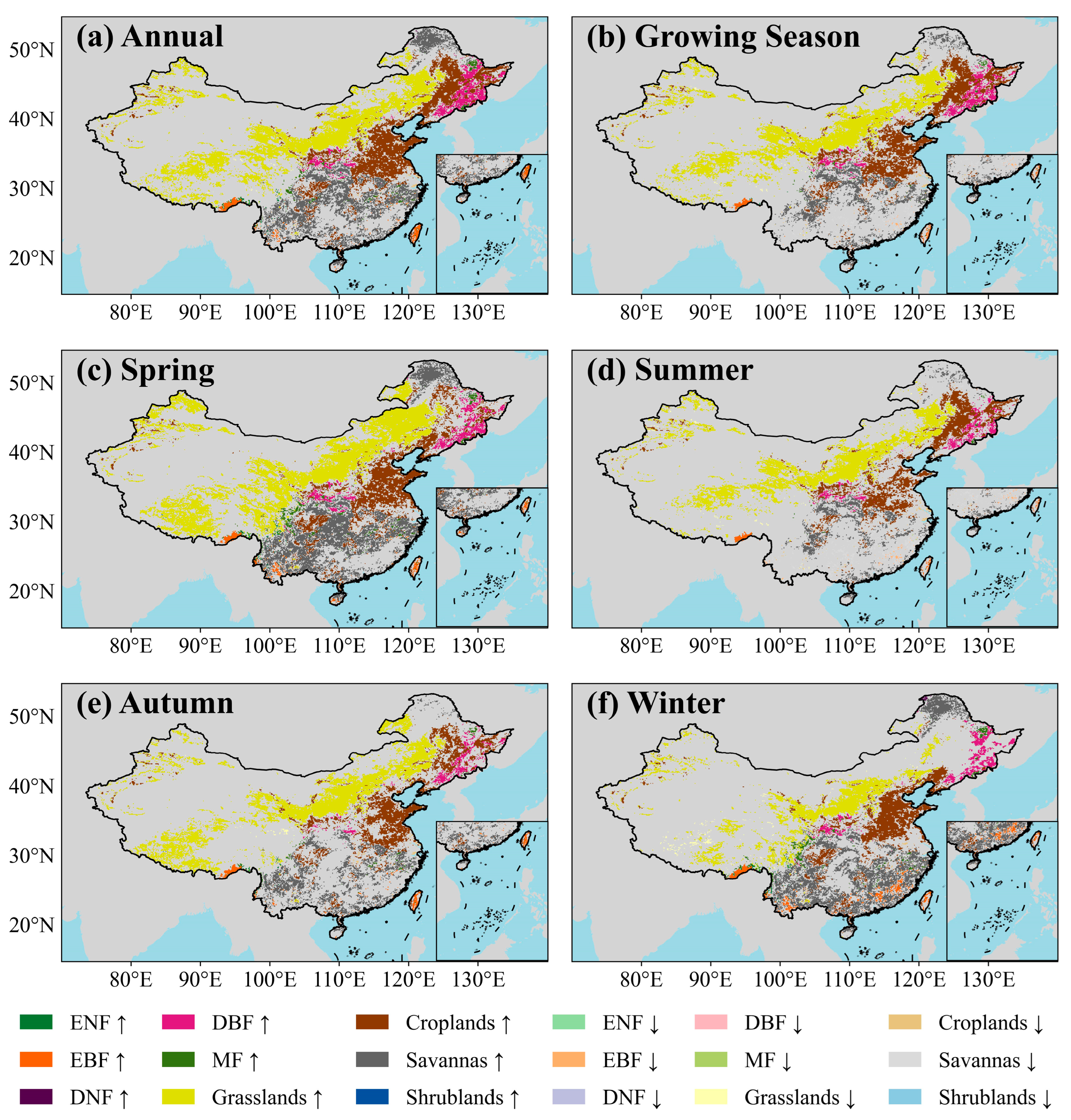

3.2. Spatio−Temporal Trends of GPP Under Different Vegetation Types

3.3. Attribution of Spatio−Temporal Variations in GPP

4. Discussion

4.1. Combined Effects of Vegetation and Climatic Factors on GPP

4.2. Combined Effects of Human Activity and Landscape Fragmentation on GPP

4.3. Implications for Ecosystem Management and Climate Adaptation

4.4. Limitations and Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beer, C.; Reichstein, M.; Tomelleri, E.; Ciais, P.; Jung, M.; Carvalhais, N.; Rödenbeck, C.; Arain, M.A.; Baldocchi, D.; Bonan, G.B.; et al. Terrestrial Gross Carbon Dioxide Uptake: Global Distribution and Covariation with Climate. Science 2010, 329, 834–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapin, F.S.; Matson, P.A.; Mooney, H. Principles of Terrestrial Ecosystem Eology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-4419-9503-2. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4811–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, D.; Stephens, B.B.; Fisher, J.B. Effect of Increasing CO2 on the Terrestrial Carbon Cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.; Evans, T.P.; Richards, K.R. National Forest Carbon Inventories: Policy Needs and Assessment Capacity. Clim. Change 2009, 93, 69–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadell, J.G.; Mooney, H.A.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Berry, J.A.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Field, C.B.; Gower, S.T.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Hunt, J.E.; Jackson, R.B.; et al. Commentary: Carbon Metabolism of the Terrestrial Biosphere: A Multitechnique Approach for Improved Understanding. Ecosystems 2000, 3, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anav, A.; Friedlingstein, P.; Beer, C.; Ciais, P.; Harper, A.; Jones, C.; Murray-Tortarolo, G.; Papale, D.; Parazoo, N.C.; Peylin, P.; et al. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Terrestrial Gross Primary Production: A Review. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 785–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Running, S.W. Drought-Induced Reduction in Global Terrestrial Net Primary Production from 2000 Through 2009. Science 2010, 329, 940–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ciais, P.; Viovy, N.; Demarty, J. Growing Season Extension and Its Impact on Terrestrial Carbon Cycle in the Northern Hemisphere over the Past 2 Decades. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 2007, 21, GB3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Nan, H.; Huntingford, C.; Ciais, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Peng, S.; Ahlström, A.; Canadell, J.G.; Cong, N.; et al. Evidence for a Weakening Relationship between Interannual Temperature Variability and Northern Vegetation Activity. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.; Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, G.; Chen, Z.; He, H.; Guo, W.; et al. Severe Summer Heatwave and Drought Strongly Reduced Carbon Uptake in Southern China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Tan, K.; Nan, H.; Ciais, P.; Fang, J.; Wang, T.; Vuichard, N.; Zhu, B. Impacts of Climate and CO2 Changes on the Vegetation Growth and Carbon Balance of Qinghai–Tibetan Grasslands over the Past Five Decades. Glob. Planet. Change 2012, 98–99, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X. Three Decades of Gross Primary Production (GPP) in China: Variations, Trends, Attributions, and Prediction Inferred from Multiple Datasets and Time Series Modeling. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, H.; Piao, S. Estimation of Gross Primary Production in China (1982–2010) with Multiple Ecosystem Models. Ecol. Model. 2016, 324, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Mo, X.; Hu, S.; Liu, S. Contributions of Climate Change, Elevated Atmospheric CO2 and Human Activities to ET and GPP Trends in the Three-North Region of China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 295, 108183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, C.; Zhang, K.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Q. Spatial–Temporal Variability of Terrestrial Vegetation Productivity in the Yangtze River Basin during 2000–2009. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 7, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Han, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, F. Divergent Impacts of Droughts on Vegetation Phenology and Productivity in the Yungui Plateau, Southwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Peng, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Liu, H.; Ma, Y.; Ding, Y.; et al. The Impacts of Climate Change on Water Resources and Agriculture in China. Nature 2010, 467, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yue, X.; Wang, B.; Tian, C.; Lu, X.; Zhu, J.; Cao, Y. Distinguishing the Main Climatic Drivers to the Variability of Gross Primary Productivity at Global FLUXNET Sites. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18, 124007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Lomas, M.; Beer, C.; Liu, H.; Fang, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Huang, Y.; Muraoka, H.; Son, Y.; et al. Contribution of Climate Change and Rising CO2 to Terrestrial Carbon Balance in East Asia: A Multi-Model Analysis. Glob. Planet. Change 2011, 75, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Elagib, N.A.; Ribbe, L.; Schneider, K. Spatio-Temporal Variations in Climate, Primary Productivity and Efficiency of Water and Carbon Use of the Land Cover Types in Sudan and Ethiopia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 790–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Pan, Y.; Yang, X.; Song, G. Comprehensive Analysis of the Impact of Climatic Changes on Chinese Terrestrial Net Primary Productivity. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 3253–3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Unger, N.; Zheng, Y. Distinguishing the Drivers of Trends in Land Carbon Fluxes and Plant Volatile Emissions over the Past 3 Decades. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 11931–11948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciais, P.; Reichstein, M.; Viovy, N.; Granier, A.; Ogée, J.; Allard, V.; Aubinet, M.; Buchmann, N.; Bernhofer, C.; Carrara, A.; et al. Europe-Wide Reduction in Primary Productivity Caused by the Heat and Drought in 2003. Nature 2005, 437, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Tian, H.; Wu, X.; Gao, Z.; Feng, Y.; Piao, S.; Lv, N.; Pan, N.; Fu, B. Accelerated Increase in Vegetation Carbon Sequestration in China after 2010: A Turning Point Resulting from Climate and Human Interaction. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 5848–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, J.; Qamer, F.M.; Latif, A.; Paul, P.K. Quantifying the Impacts of Anthropogenic Activities and Climate Variations on Vegetation Productivity Changes in China from 1985 to 2015. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, W.; Li, M.; Li, N.; Shi, Z.; Dong, J.; Xiao, X. Urbanization Expands the Fluctuating Difference in Gross Primary Productivity between Urban and Rural Areas from 2000 to 2018 in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 901, 166490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Liang, H.; Ma, Y.; Xue, G.; He, J. The Impacts of Climate and Human Activities on Grassland Productivity Variation in China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Ma, W.; Zhuang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, S.; Xu, J.; Long, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhang, Z. The Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Alpine Vegetation and Permafrost in the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Gang, C.; Shen, Y. Quantifying the Contributions of Climate Change and Human Activities to Vegetation Dynamic in China Based on Multiple Indices. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapley, L.S. A Value for n-Person Games. In Contributions to the Theory of Games, Volume II; Kuhn, H.W., Tucker, A.W., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1953; pp. 307–318. ISBN 978-1-4008-8197-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.; Yue, X.; Dai, H.; Geng, G.; Yuan, W.; Chen, J.; Shen, G.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, J.; Liao, H. Recovery of Ecosystem Productivity in China Due to the Clean Air Action Plan. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 1233–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Lutsko, N.J.; Dufour, A.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, X.; van Dijk, A.I.J.M.; Miralles, D.G. High-Resolution (1 Km) Köppen-Geiger Maps for 1901–2099 Based on Constrained CMIP6 Projections. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, N.; Tian, J.; Kong, D.; Liu, C. A Daily and 500m Coupled Evapotranspiration and Gross Primary Production Product across China during 2000–2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 5463–5488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, L.; Fan, J.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, X. Assessing and Improving the High Uncertainty of Global Gross Primary Productivity Products Based on Deep Learning under Extreme Climatic Conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulla-Menashe, D.; Friedl, M.A. User Guide to Collection 6 MODIS Land Cover (MCD12Q1 and MCD12C1) Product; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bajgain, R.; Xiao, X.; Basara, J.; Wagle, P.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mahan, H. Assessing Agricultural Drought in Summer over Oklahoma Mesonet Sites Using the Water-Related Vegetation Index from MODIS. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, K.; Tang, W.; Lu, H.; Qin, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, X. The First High-Resolution Meteorological Forcing Dataset for Land Process Studies over China. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wu, S.; Zhang, K.; Wan, M.; Wang, R. A New Global Grid-Based Weighted Mean Temperature Model Considering Vertical Nonlinear Variation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 2529–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, B.; Yan, N.; Zhu, W.; Feng, X. An Improved Satellite-Based Approach for Estimating Vapor Pressure Deficit from MODIS Data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 12256–12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Yin, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, J. Use of General Regression Neural Networks for Generating the GLASS Leaf Area Index Product from Time-Series MODIS Surface Reflectance. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Liang, S.; Jiang, B. Evaluation of Four Long Time-Series Global Leaf Area Index Products. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2017, 246, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, J.; Park, T.; Liu, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Yin, G.; Zhao, J.; Fan, W.; Yang, L.; Knyazikhin, Y.; et al. An Integrated Method for Validating Long-Term Leaf Area Index Products Using Global Networks of Site-Based Measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ran, M.; Xia, H.; Deng, M. Evaluating Vertical Accuracies of Open-Source Digital Elevation Models over Multiple Sites in China Using GPS Control Points. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, E.W.; Fisher, K.; Robinson, N.; Sampson, D.; Duncan, A.; Royte, L. The March of the Human Footprint. EcoEvoRxiv Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hao, J.-Q.; Dai, Z.-Z.; Haider, S.; Chang, S.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Duan, J.; Ren, G.-X. Spatial-Temporal Characteristics of Cropland Distribution and Its Landscape Fragmentation in China. Farming Syst. 2024, 2, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Non-Parametric Tests against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, P.A.P.; Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods. Int. Stat. Rev. 1973, 41, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the Regression Coefficient Based on Kendall’s Tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 324, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theil, H. A Rank-Invariant Method of Linear and Polynomial Regression Analysis. Proc. R. Neth. Acad. Sci. 1950, 53, 386–392. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, H. Exploring the Impact of Natural and Human Activities on Vegetation Changes: An Integrated Analysis Framework Based on Trend Analysis and Machine Learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 124092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, F.; Liu, F. SHAP-Powered Insights into Short-Term Drought Dynamics Disturbed by Diurnal Temperature Range across China. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 316, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Xu, Y.; Pi, J.; Li, Y.; Ke, C.; Zhan, W.; Chen, J. Widespread Sensitivity of Vegetation to the Transition from Normal Droughts to Flash Droughts. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL114321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Kojadinovic, I.; Marichal, J.-L. Axiomatic Characterizations of Probabilistic and Cardinal-Probabilistic Interaction Indices. Games Econ. Behav. 2006, 55, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabisch, M.; Roubens, M. An Axiomatic Approach to the Concept of Interaction among Players in Cooperative Games. Int. J. Game Theory 1999, 28, 547–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Xue, Y.; Pan, N.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, H.; Zhang, F. Exploring the Spatiotemporal Alterations in China’s GPP Based on the DTEC Model. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Qiao, C.; Du, L.; Tang, E.; Wu, H.; Shi, G.; Xue, B.; Wang, Y.; Lucas-Borja, M.E. Drought in the Middle Growing Season Inhibited Carbon Uptake More Critical in an Anthropogenic Shrub Ecosystem of Northwest China. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 353, 110060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Shen, M.; Du, M.; He, H.; Li, Y.; Luo, W.; Ma, M.; et al. Spatiotemporal Pattern of Gross Primary Productivity and Its Covariation with Climate in China over the Last Thirty Years. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Buttlar, J.; Zscheischler, J.; Rammig, A.; Sippel, S.; Reichstein, M.; Knohl, A.; Jung, M.; Menzer, O.; Arain, M.A.; Buchmann, N.; et al. Impacts of Droughts and Extreme-Temperature Events on Gross Primary Production and Ecosystem Respiration: A Systematic Assessment across Ecosystems and Climate Zones. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 1293–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.-F.; Fu, Y.-S. Effect of Growing Season Length on Gross Primary Productivity Increased in the Jinsha River Watershed. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtae108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Cao, Y.; Tian, J.; Ren, B. Increased Contribution of Extended Vegetation Growing Season to Boreal Terrestrial Ecosystem GPP Enhancement. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, S.; Gu, Z.; Li, W.; Cui, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, S. Estimating GPP in China Using Different Site-Level Datasets, Vegetation Classification and Vegetation Indices. Ecol. Process. 2025, 14, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Xu, Y.; Longo, M.; Keller, M.; Knox, R.G.; Koven, C.D.; Fisher, R.A. Assessing Impacts of Selective Logging on Water, Energy, and Carbon Budgets and Ecosystem Dynamics in Amazon Forests Using the Functionally Assembled Terrestrial Ecosystem Simulator. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 4999–5023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Jin, C.; Dong, J.; Zhou, S.; Wagle, P.; Joiner, J.; Guanter, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; et al. Consistency between Sun-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Gross Primary Production of Vegetation in North America. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 183, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Du, S.; Liu, L.; Jing, X. Investigating the Performance of Red and Far-Red SIF for Monitoring GPP of Alpine Meadow Ecosystems. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shen, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, S.; Liang, S.; Chen, J.M.; Ju, W.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, W. Improved Estimate of Global Gross Primary Production for Reproducing Its Long-Term Variation, 1982–2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 2725–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yang, G.; Fang, K.; Wang, G.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhou, G.; Yang, Y. Leaf Area Rather Than Photosynthetic Rate Determines the Response of Ecosystem Productivity to Experimental Warming in an Alpine Steppe. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2019, 124, 2277–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.M.; Ju, W.; Migliavacca, M.; El-Madany, T.S. Sensitivity of Estimated Total Canopy SIF Emission to Remotely Sensed LAI and BRDF Products. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021, 9795837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, L. Effects of Low Temperature on the Relationship between Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence and Gross Primary Productivity across Different Plant Function Types. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.N.; Stark, S.C.; Taylor, T.C.; Ferreira, M.L.; de Oliveira, E.; Restrepo-Coupe, N.; Chen, S.; Woodcock, T.; dos Santos, D.B.; Alves, L.F.; et al. Seasonal and Drought-Related Changes in Leaf Area Profiles Depend on Height and Light Environment in an Amazon Forest. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1284–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Pacheco-Labrador, J.; Migliavacca, M.; Miralles, D.; Hoek van Dijke, A.; Reichstein, M.; Forkel, M.; Zhang, W.; Frankenberg, C.; Panwar, A.; et al. Widespread and Complex Drought Effects on Vegetation Physiology Inferred from Space. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Prentice, I.C.; Gentine, P.; Makowski, D.; Bastos, A.; Luo, X.; Green, J.K.; Stoy, P.C.; Yang, H.; et al. Atmospheric Dryness Reduces Photosynthesis along a Large Range of Soil Water Deficits. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Peng, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Dou, T.; Chen, J.; Wu, X. SIF-Based GPP Is a Useful Index for Assessing Impacts of Drought on Vegetation: An Example of a Mega-Drought in Yunnan Province, China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, M.; Cescatti, A.; Duveiller, G. Sun-Induced Fluorescence as a Proxy for Primary Productivity across Vegetation Types and Climates. Biogeosciences 2022, 19, 4833–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gudmundsson, L.; Hauser, M.; Qin, D.; Li, S.; Seneviratne, S.I. Soil Moisture Dominates Dryness Stress on Ecosystem Production Globally. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, J.; Liu, Q.; Huete, A.; Li, L. Effects of Forest Canopy Vertical Stratification on the Estimation of Gross Primary Production by Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Decoupling and Insensitivity of Greenness and Gross Primary Productivity Across Aridity Gradients in China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Lessa Derci Augustynczik, A.; Havlík, P.; Boere, E.; Ermolieva, T.; Fricko, O.; Di Fulvio, F.; Gusti, M.; Krisztin, T.; Lauri, P.; et al. Enhanced Agricultural Carbon Sinks Provide Benefits for Farmers and the Climate. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Zhou, H.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Q.; Hu, S. Distinguishing the Main Climatic Drivers of Terrestrial Vegetation Carbon Dynamics in Pan-Arctic Ecosystems. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B.; Doney, S.C. Climate, Ecosystems, and Planetary Futures: The Challenge to Predict Life in Earth System Models. Science 2018, 359, eaam8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hari, M.; Tyagi, B. Terrestrial Carbon Cycle: Tipping Edge of Climate Change between the Atmosphere and Biosphere Ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Atmos. 2022, 2, 867–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Y. Human Activities Unevenly Disturbed Climatic Impacts on Vegetation Dynamics across Natural-Anthropogenic-Integrated Ecosystem Types in China. Habitat Int. 2025, 162, 103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.; Zhao, J.; Guo, X.; Ying, H.; Deng, G.; Rihan, W.; Wang, S. Vegetation Productivity Dynamics in Response to Climate Change and Human Activities under Different Topography and Land Cover in Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; He, X.; Wang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Xiang, H.; Yu, H.; Man, W.; Jia, M.; Ren, C.; Zheng, H. Diverse Policies Leading to Contrasting Impacts on Land Cover and Ecosystem Services in Northeast China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 117961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Peng, C.; Li, W.; Tian, L.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, G.; Mu, X.; et al. Multiple Afforestation Programs Accelerate the Greenness in the ‘Three North’ Region of China from 1982 to 2013. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Cheng, Y.; Hong, P.; Ma, J.; Yao, L.; Jiang, B.; Xu, X.; Wu, C. Impact of Fragmentation on Carbon Uptake in Subtropical Forest Landscapes in Zhejiang Province, China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, B.; Seyoum, G. Human Interventions Have Enhanced the Net Ecosystem Productivity of Farmland in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Niu, S.; Ciais, P.; Janssens, I.A.; Chen, J.; Ammann, C.; Arain, A.; Blanken, P.D.; Cescatti, A.; Bonal, D.; et al. Joint Control of Terrestrial Gross Primary Productivity by Plant Phenology and Physiology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2788–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, J.B.; Huntzinger, D.N.; Schwalm, C.R.; Sitch, S. Modeling the Terrestrial Biosphere. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2014, 39, 91–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Effects of Changing Scale on Landscape Pattern Analysis: Scaling Relations. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; O’Neill, R.V.; Gardner, R.H.; Milne, B.T. Effects of Changing Spatial Scale on the Analysis of Landscape Pattern. Landsc. Ecol. 1989, 3, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Schwalm, C.; Migliavacca, M.; Walther, S.; Camps-Valls, G.; Koirala, S.; Anthoni, P.; Besnard, S.; Bodesheim, P.; Carvalhais, N.; et al. Scaling Carbon Fluxes from Eddy Covariance Sites to Globe: Synthesis and Evaluation of the FLUXCOM Approach. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1343–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shen, W.; Sun, W.; Tueller, P.T. Empirical Patterns of the Effects of Changing Scale on Landscape Metrics. Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 17, 761–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-S.; Piao, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ciais, P.; Zhou, L.; Li, L.Z.X.; Myneni, R.B.; Yin, Y.; Zeng, H. Afforestation in China Cools Local Land Surface Temperature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 2915–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, E.W.; Jaiteh, M.; Levy, M.A.; Redford, K.H.; Wannebo, A.V.; Woolmer, G. The Human Footprint and the Last of the Wild: The Human Footprint Is a Global Map of Human Influence on the Land Surface, Which Suggests That Human Beings Are Stewards of Nature, Whether We like It or Not. BioScience 2002, 52, 891–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, O.; Sanderson, E.W.; Magrach, A.; Allan, J.R.; Beher, J.; Jones, K.R.; Possingham, H.P.; Laurance, W.F.; Wood, P.; Fekete, B.M.; et al. Global Terrestrial Human Footprint Maps for 1993 and 2009. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Diao, Y.; Lai, J.; Huang, L.; Wang, A.; Wu, J.; Liu, Y.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, R.; Fei, W.; et al. Impacts of Climate Change, Human Activities, and Their Interactions on China’s Gross Primary Productivity. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020275

Diao Y, Lai J, Huang L, Wang A, Wu J, Liu Y, Shen L, Zhang Y, Cai R, Fei W, et al. Impacts of Climate Change, Human Activities, and Their Interactions on China’s Gross Primary Productivity. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020275

Chicago/Turabian StyleDiao, Yiwei, Jie Lai, Lijun Huang, Anzhi Wang, Jiabing Wu, Yage Liu, Lidu Shen, Yuan Zhang, Rongrong Cai, Wenli Fei, and et al. 2026. "Impacts of Climate Change, Human Activities, and Their Interactions on China’s Gross Primary Productivity" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020275

APA StyleDiao, Y., Lai, J., Huang, L., Wang, A., Wu, J., Liu, Y., Shen, L., Zhang, Y., Cai, R., Fei, W., & Zhou, H. (2026). Impacts of Climate Change, Human Activities, and Their Interactions on China’s Gross Primary Productivity. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 275. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020275