A New Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) Retrieval Algorithm for Spaceborne L-Band Brightness Temperature (TB) Data

Highlights

- A novel L-band sea ice concentration retrieval algorithm has been developed, which systematically quantifies and constrains four key uncertainties—particularly the Diurnal Amplitude Variation (DAV) signal associated with sea ice freeze–thaw cycles.

- DAV exhibits the most pronounced effect on the precision of the sea ice concentration retrieval algorithm; constraining all four key uncertainties together achieves a further reduction in RMSE to 7.42%.

- The novel L-band sea ice concentration retrieval algorithm consistently demonstrates high agreement with SSM/I, ship-based SIC data, and SAR SIC, supporting its reliability under various validation scenarios.

- Integrating the DAV signal into future retrieval models can enhance the understanding of sea ice freeze–thaw processes and improve ice-atmosphere interaction studies in climate modeling and data assimilation.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data

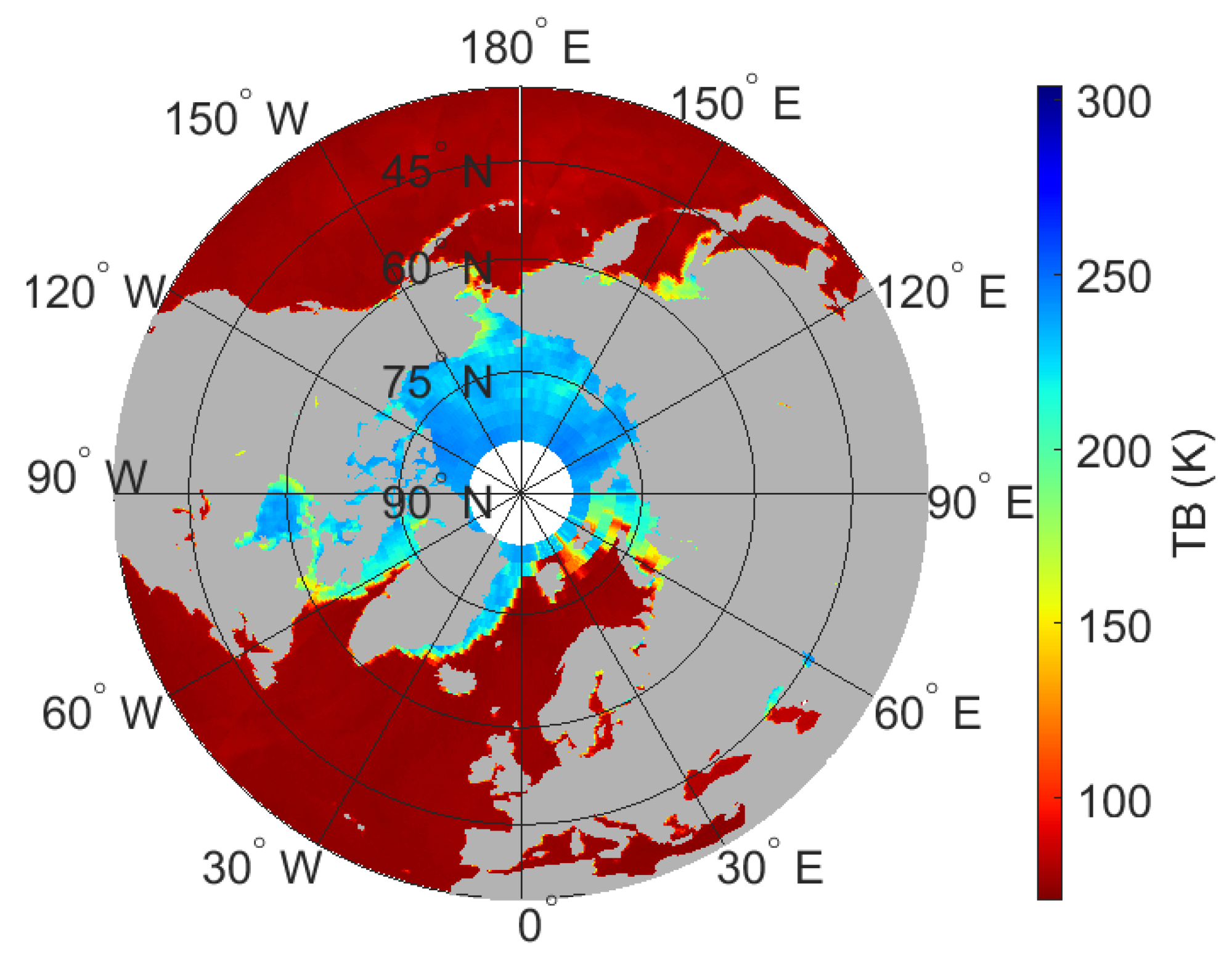

2.1. Core Input: SMAP L-Band Brightness Temperature

2.2. Constraint and Endmember Definition: ERA5 Reanalysis

2.3. Primary Reference: SSM/I-SSMIS Sea Ice Concentration

2.4. Independent Validation Data

- (1)

- Ship-Based Observations: Visual SIC estimates from the ICEWatch/ASSIST program (https://cryo.met.no/en/icewatch) (accessed on 25 February 2025) [55] provide in situ point measurements within an approximate 1 km radius of the vessel. Observers use integer values from 0 to 10 to describe the sea ice conditions, corresponding to SIC ranging from open water (0%) to consolidated ice (100%). Following the method of Beitsch et al. [56], each daily ship record is matched to the nearest satellite grid cell for comparison, offering a ground-truth perspective.

- (2)

- High-Resolution SAR SIC: This study has been conducted using E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information, specifically the SAR sea ice concentration (SIC) product; https://doi.org/10.48670/mds-00344 (accessed on 24 November 2025) [57]. The 1 km resolution Arctic Ocean High-Resolution Sea Ice L4 product, which blends Sentinel-1 and RCM SAR imagery and GCOM-W AMSR2 microwave radiometer data using deep learning methods, provides a spatially detailed reference. For a fair comparison at the SMAP scale, all 1 km pixels within a given SMAP grid cell are averaged to produce a single, co-located reference SIC value for validation against both the new L-band and resampled SSM/I SIC.

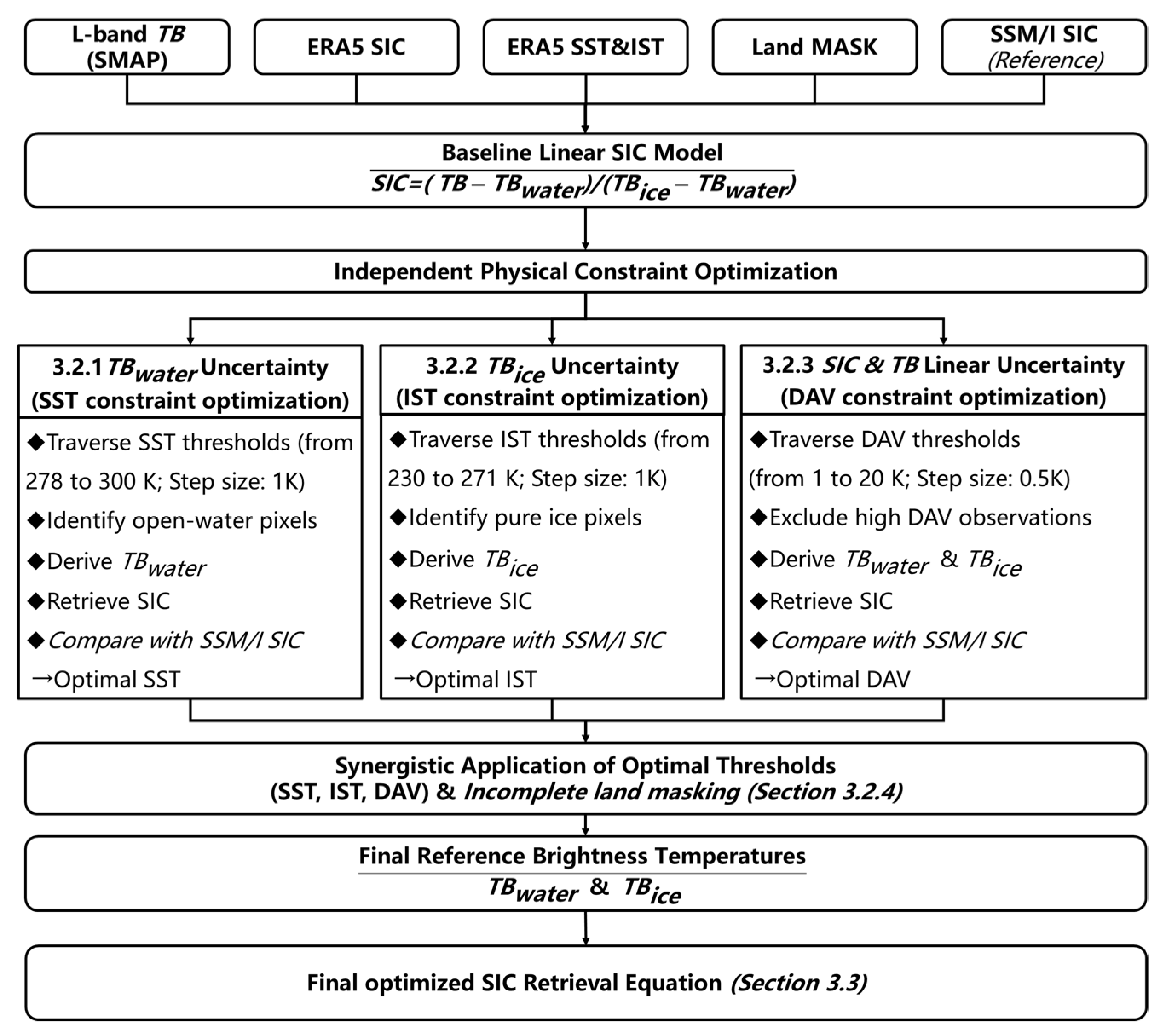

3. Methods

3.1. Single-Channel Algorithm

3.2. Parameter Calibration and Uncertainty Minimization for SIC Retrieval

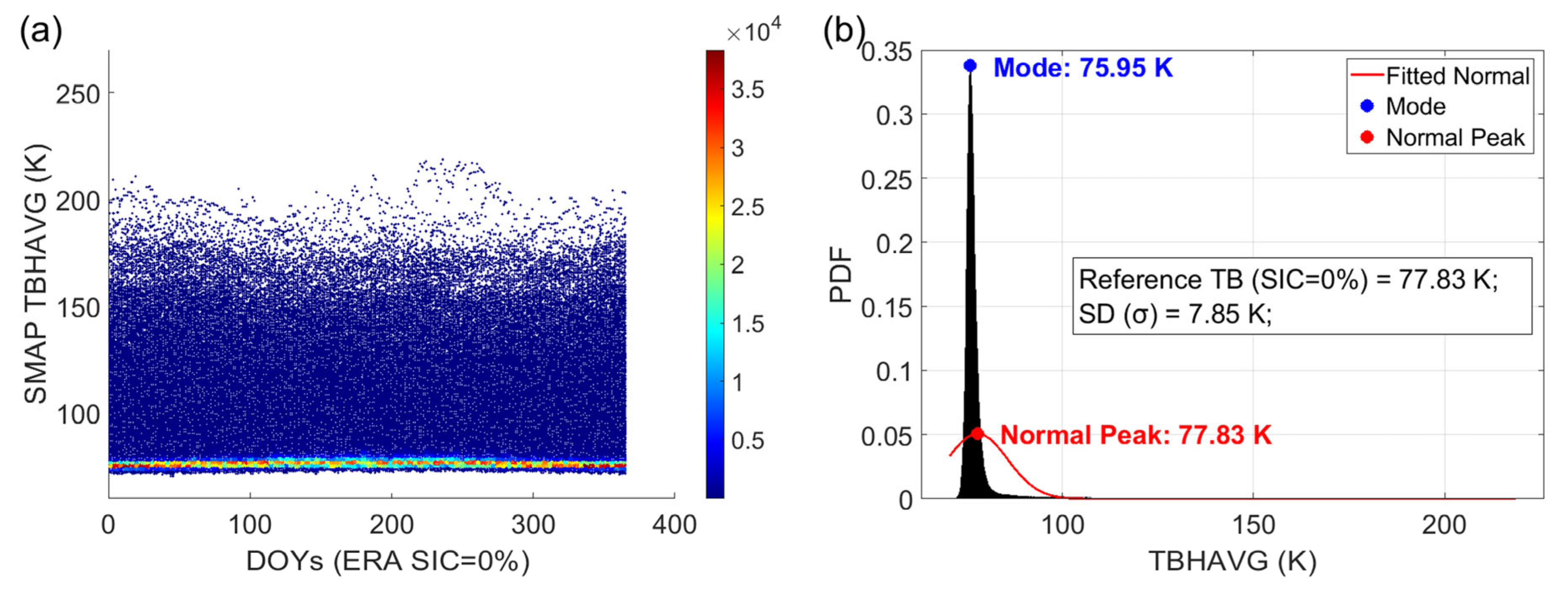

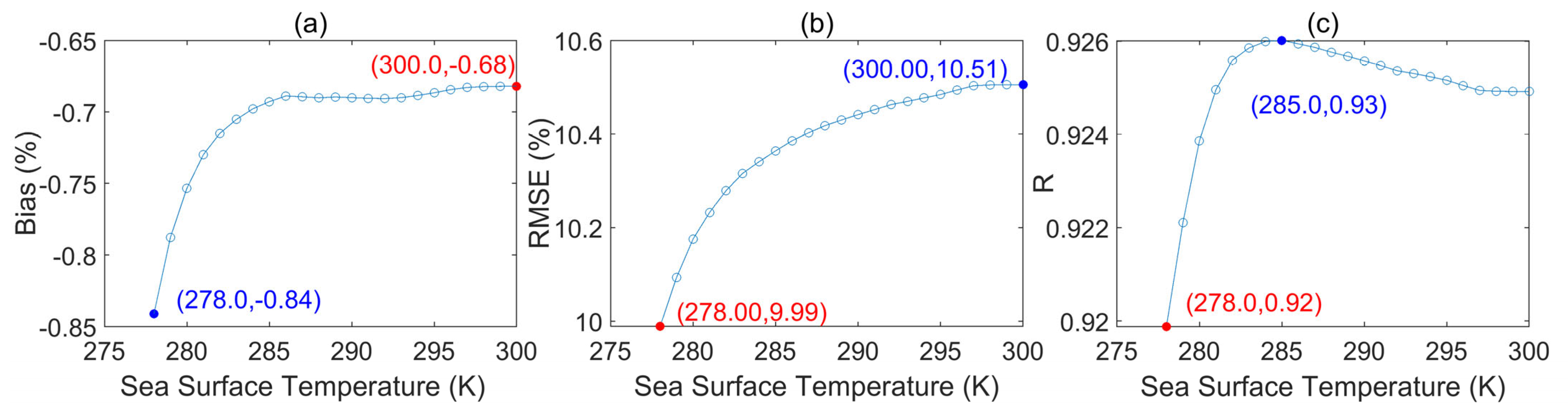

3.2.1. Seawater Reference TB (TBwater) and Uncertainty Optimization

3.2.2. Sea Ice Reference TB (TBice) and Uncertainty Optimization

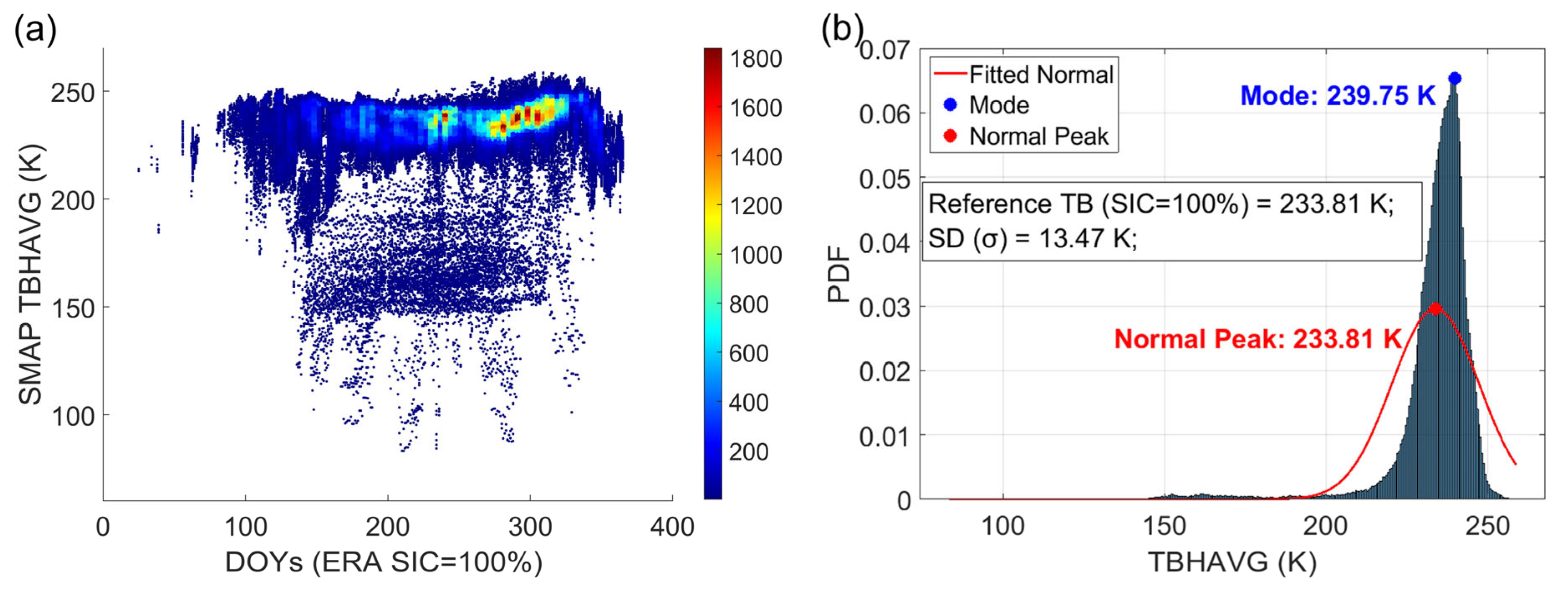

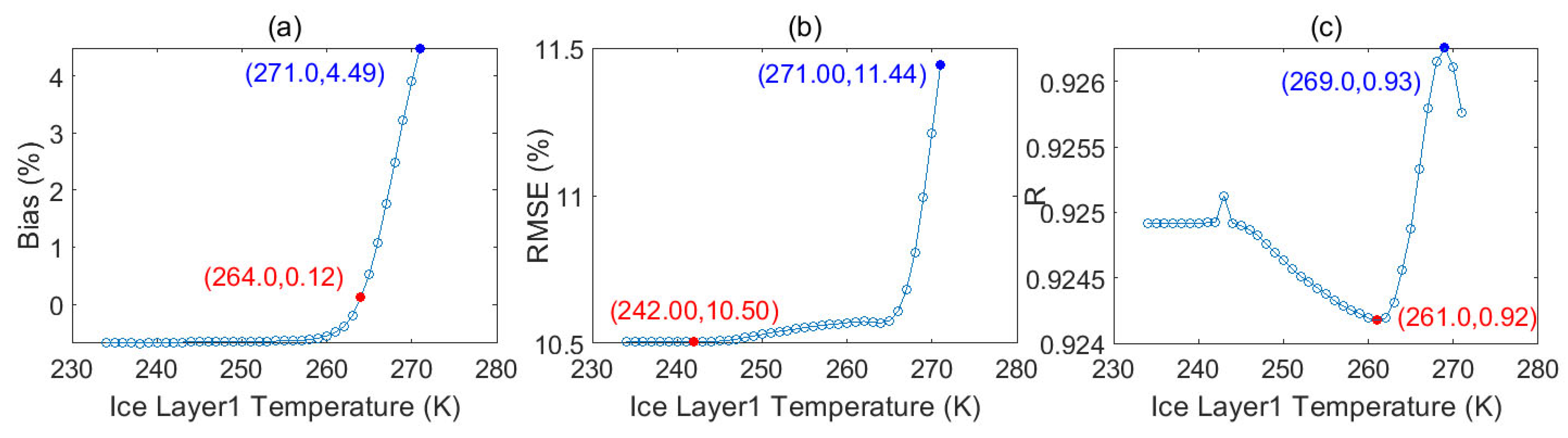

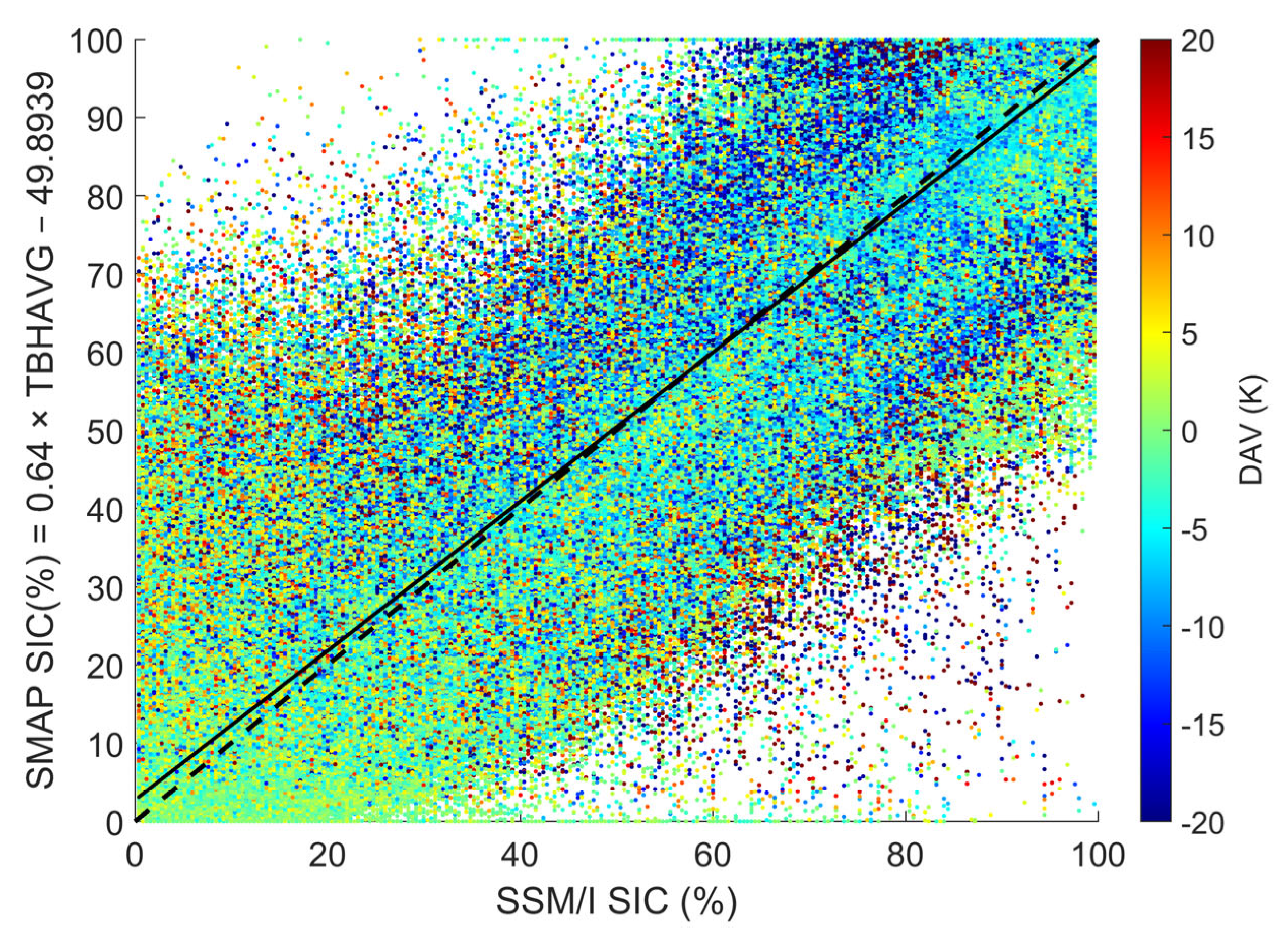

3.2.3. Establishing and Optimizing the Linear Relationship Between SIC and TB

3.2.4. Additional Uncertainty from Spatial Resolution and Land Masking

3.3. Final Reference TB and SIC Retrieval Algorithm

3.4. Justification for Using Single Horizontal Polarized TB as Core Input

4. Results

4.1. SIC Retrieval Results with Stepwise Uncertainty Treatments

4.1.1. Raw SIC Retrieval Without Any Uncertainty Mitigation

4.1.2. SIC Retrieval After Removing Only the Uncertainties of TBwater

4.1.3. SIC Retrieval After Removing Only the Uncertainties of TBicer

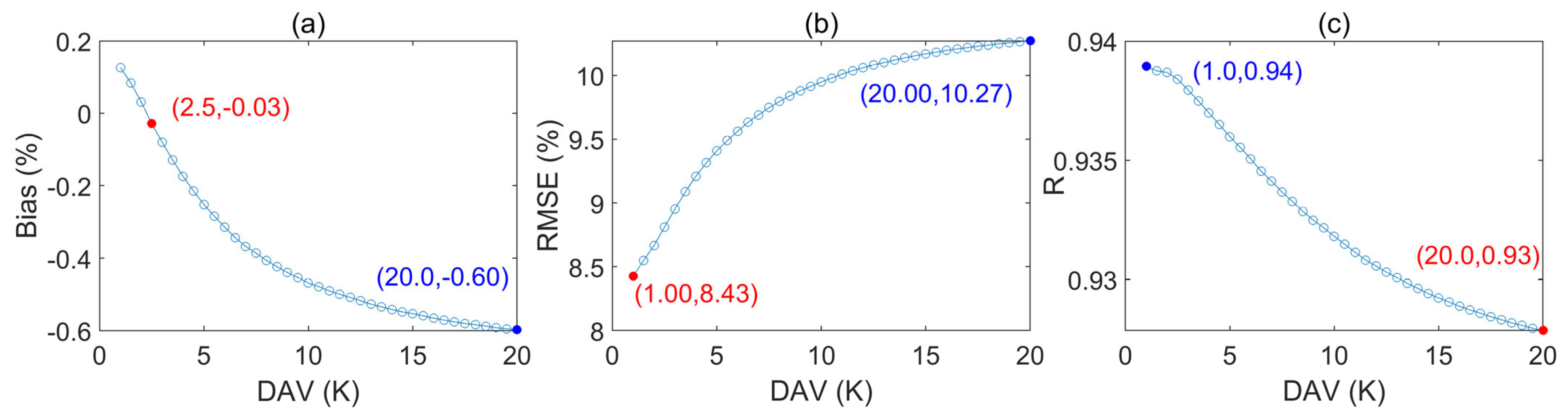

4.1.4. SIC Retrieval After Removing Only the Uncertainties of DAV Signals Caused by Sea Ice Freeze–Thaw

4.1.5. SIC Retrieval After Removing Only the Uncertainties of Incomplete Land Masking

4.1.6. Final SIC Retrieval After Removing Uncertainties of TBwater, TBice, DAV, and Incomplete Land Masking

4.1.7. Stepwise Optimization and Error Reduction

4.2. Monthly Tests for Algorithm Robustness Assessment

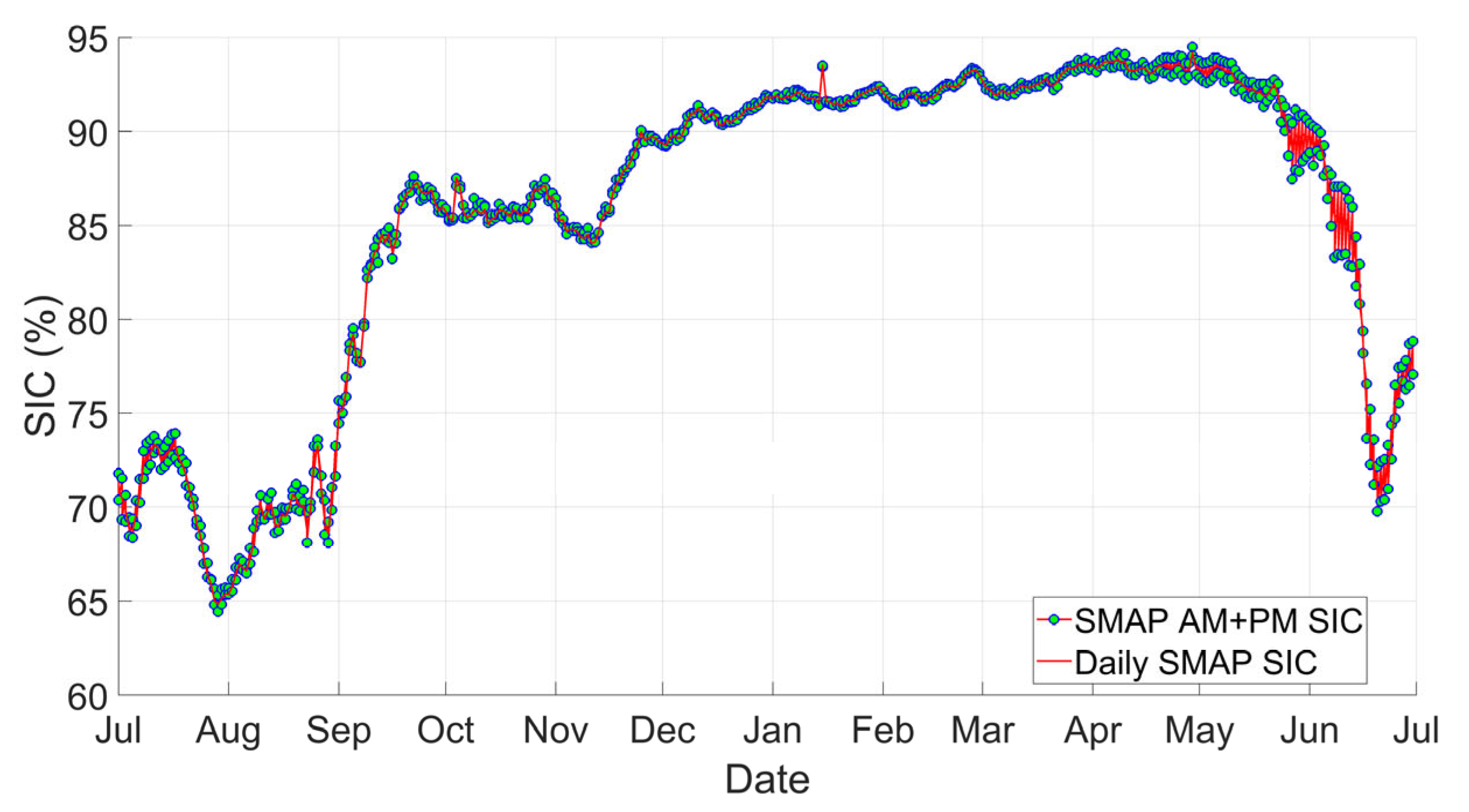

4.3. Seasonal Variability of New L-Band Algorithm SIC and SSM/I SIC

4.4. Validation Against Ship-Based SIC Observations

4.5. Validation Against SAR SIC Observations

5. Discussion

5.1. Linking DAV Signal to the Sea-Ice Surface Freeze–Thaw Process

5.2. Advantage of DAV Signal

5.3. Application and Limitations of ERA5 SIC in Endmember Definition

5.4. Challenges in Obtaining Validation Data

5.5. Impact of Sea Ice Thickness

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Compared to SSM/I SIC, DAV has the most significant influence on the accuracy of the SIC retrieval algorithm. By eliminating the uncertainties of DAV caused by sea ice freeze–thaw processes, RMSE decreases from 10.51% to 8.43%, and R improves from 0.92 to 0.94. Bias value also decreases from −0.68% to 0.12%. After eliminating four uncertainties, a retrieval algorithm for SIC is established under ideal conditions. RMSE further reduces to 7.42% (approximately a 3% reduction). Besides, the difference between the algorithm and SSM/I SIC in winter is much smaller than that in summer. R values mostly exceed 0.9 for twelve months, RMSE is mostly below 10%, and Bias is mostly less than 5%. Consequently, both datasets reveal a high degree of consistency in capturing seasonal trends of sea ice contraction and expansion.

- (2)

- Compared to ship-based SIC data, the algorithm shows high accuracy and consistency, especially under low SIC conditions, even outperforming SSM/I. Bias, RMSE, and MAE are approximately 2%, 2%, and 2% higher than those of SSM/I SIC. The differences mainly appear in the Greenland Sea, while other areas show consistency.

- (3)

- Compared with ship measurements, the L-band and SSM/I satellites show slightly worse validation against SAR, with Bias, RMSE, and MAE about 2%, 1%, and 2% higher, respectively. Over Greenland, there may be localized overestimation, but most areas are underestimated.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lei, R.; Tian-Kunze, X.; Leppäranta, M.; Wang, J.; Kaleschke, L.; Zhang, Z. Changes in summer sea ice, albedo, and portioning of surface solar radiation in the Pacific sector of Arctic Ocean during 1982–2009. J. Geophys. Res. 2016, 121, 5470–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopsch, S.; Cohen, J.; Dethloff, K. Analysis of a link between fall Arctic sea ice concentration and atmospheric patterns in the following winter. Tellus A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 2012, 64, 18624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodetskaya, I.V.; Cane, M.A.; Tremblay, L.B.; Kaplan, A. The effects of sea-ice and land-snow concentrations on planetary albedo from the earth radiation budget experiment. Atmos. Ocean 2006, 44, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, W.N.; Hovelsrud, G.K.; van Oort, B.E.H.; Key, J.R.; Kovacs, K.M.; Michel, C.; Haas, C.; Granskog, M.A.; Gerland, S.; Perovich, D.K.; et al. Arctic sea ice in transformation: A review of recent observed changes and impacts on biology and human activity. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 185–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struthers, H.; Ekman, A.M.L.; Glantz, P.; Iversen, T.; Kirkevåg, A.; Mårtensson, E.M.; Seland, Ø.; Nilsson, E.D. The effect of sea ice loss on sea salt aerosol concentrations and the radiative balance in the Arctic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 3459–3477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, E.G. Passive microwave remote sensing of the earth from space—A review. Proc. IEEE 1982, 70, 728–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyasu, K. Remote sensing of the earth by microwaves. Proc. IEEE 1974, 62, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, E.G.; Stacey, J.M.; Barath, F.T. The Seasat scanning multichannel microwave radiometer (SMMR): Instrument description and performance. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 1980, 5, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comiso, J.C. Enhanced Sea Ice Concentrations and Ice Extents from AMSR-E Data. J. Remote Sens. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 29, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalieri, D.J.; Gloersen, P.; Campbell, W.J. Determination of sea ice parameters with the NIMBUS 7 SMMR. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1984, 89, 5355–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comiso, J.C. Characteristics of Arctic winter sea ice from satellite multispectral microwave observations. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1986, 91, 975–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, L.T. Retrieval of Sea Ice Concentration by Means of Microwave Radiometry. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, T.; Cavalieri, D.J. An enhancement of the NASA Team sea ice algorithm. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2000, 38, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreen, G.; Kaleschke, L.; Heygster, G.C. Sea ice remote sensing using AMSR-E 89-GHz channels. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Pang, X.; Ji, Q. Daily sea ice concentration product based on brightness temperature data of FY-3D MWRI in the Arctic. Big Earth Data 2022, 6, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Kern, S.; Qu, M.; Ji, Q.; Fan, P.; Liu, Y. Sea Ice Concentration Derived From FY-3D MWRI and Its Accuracy Assessment. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4300418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonboe, R.T.; Nandan, V.; Mäkynen, M.; Pedersen, L.T.; Kern, S.; Lavergne, T.; Øelund, J.; Dybkjær, G.; Saldo, R.; Huntemann, M. Simulated Geophysical Noise in Sea Ice Concentration Estimates of Open Water and Snow-Covered Sea Ice. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 1309–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Scarlat, R.; Heygster, G.; Spreen, G. Reducing Weather Influences on an 89 GHz Sea Ice Concentration Algorithm in the Arctic Using Retrievals from an Optimal Estimation Method. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2022, 127, e2019JC015912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, T.; Sørensen, A.M.; Kern, S.; Tonboe, R.; Notz, D.; Aaboe, S.; Bell, L.; Dybkjær, G.; Eastwood, S.; Gabarro, C.; et al. Version 2 of the EUMETSAT OSI SAF and ESA CCI sea-ice concentration climate data records. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 49–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Scott, K.A.; Clausi, D.A. Sea Ice Concentration Estimation during Freeze-Up from SAR Imagery Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, C.L.V.; Scott, K.A. Estimating Sea Ice Concentration From SAR: Training Convolutional Neural Networks with Passive Microwave Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 57, 4735–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, J.; Kim, H.-c.; Lee, S.; Crawford, M.M. Deep learning based retrieval algorithm for Arctic sea ice concentration from AMSR2 passive microwave and MODIS optical data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.; Pedersen, L.T.; Tonboe, R.T.; Kern, S.; Heygster, G.; Lavergne, T.; Sørensen, A.; Saldo, R.; Dybkjær, G.; Brucker, L.; et al. Inter-comparison and evaluation of sea ice algorithms: Towards further identification of challenges and optimal approach using passive microwave observations. Cryosphere 2015, 9, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.; Johannessen, O.M.; Pedersen, L.T.; Tonboe, R.T. Retrieval of Arctic Sea Ice Parameters by Satellite Passive Microwave Sensors: A Comparison of Eleven Sea Ice Concentration Algorithms. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2014, 52, 7233–7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattsov, V.M.; Ryabinin, V.E.; Overland, J.E.; Serreze, M.C.; Visbeck, M.; Walsh, J.E.; Meier, W.; Zhang, X. Arctic sea-ice change: A grand challenge of climate science. J. Glaciol. 2010, 56, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, S.; Lavergne, T.; Notz, D.; Pedersen, L.T.; Tonboe, R. Satellite passive microwave sea-ice concentration data set inter-comparison for Arctic summer conditions. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 2469–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, S.; Lavergne, T.; Notz, D.; Pedersen, L.T.; Tonboe, R.T.; Saldo, R.; Sørensen, A.M. Satellite passive microwave sea-ice concentration data set intercomparison: Closed ice and ship-based observations. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 3261–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietsche, S.; Alonso-Balmaseda, M.; Rosnay, P.; Zuo, H.; Tian-Kunze, X.; Kaleschke, L. Thin Arctic sea ice in L-band observations and an ocean reanalysis. Cryosphere 2018, 12, 2051–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Balmaseda, M.A.; Tietsche, S.; Mogensen, K.; Mayer, M. The ECMWF operational ensemble reanalysis–analysis system for ocean and sea ice: A description of the system and assessment. Ocean Sci. 2019, 15, 779–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.D.; Donlon, C.J.; Martin, M.J.; McCulloch, M.E. OSTIA: An operational, high resolution, real time, global sea surface temperature analysis system. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2007-Europe, Aberdeen, UK, 18–21 June 2007; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fichefet, T.; Maqueda, M.A.M. Sensitivity of a global sea ice model to the treatment of ice thermodynamics and dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1997, 102, 12609–12646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosnay, P.; Browne, P.; de Boisséson, E.; Fairbairn, D.; Hirahara, Y.; Ochi, K.; Schepers, D.; Weston, P.; Zuo, H.; Alonso-Balmaseda, M.; et al. Coupled data assimilation at ECMWF: Current status, challenges and future developments. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 148, 2672–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarro, C.; Turiel, A.; Elosegui, P.; Pla-Resina, J.A.; Portabella, M. New methodology to estimate Arctic sea ice concentration from SMOS combining brightness temperature differences in a maximum-likelihood estimator. Cryosphere 2017, 11, 1987–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P.; Heygster, G. Retrieving Ice Concentration From SMOS. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2011, 8, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, L.; Prigent, C.; Aires, F.; Boutin, J.; Heygster, G.; Tonboe, R.T.; Roquet, H.; Jimenez, C.; Donlon, C. Expected Performances of the Copernicus Imaging Microwave Radiometer (CIMR) for an All-Weather and High Spatial Resolution Estimation of Ocean and Sea Ice Parameters. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2018, 123, 7564–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, S.; Tonboe, R.T.; Kern, S.; Schyberg, H. Improved retrieval of sea ice total concentration from spaceborne passive microwave observations using numerical weather prediction model fields: An intercomparison of nine algorithms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 104, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikainen, M.; Winebrenner, D.P. The physical basis for sea ice remote sensing. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 1992, 68, 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, W.B., III; Perovich, D.K.; Gow, A.J.; Weeks, W.F.; Drinkwater, M.R. Physical properties of sea ice relevant to remote sensing. Geophys. Monogr. Ser. 1992, 68, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Semmens, K.A.; Ramage, J.M. Recent changes in spring snowmelt timing in the Yukon River basin detected by passive microwave satellite data. Cryosphere 2013, 7, 905–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lv, S.; Guo, Y.; Bai, H.; Dorjsuren, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, J. Advantage of Diurnal Amplitude Variation (DAV) of Brightness Temperature in Revealing the Land-Atmosphere Interaction Over the Region of Frozen and Thawed Soil in the Northern Hemisphere During the Cold Wave Movements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2025, 52, e2024GL114485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Zhao, T.; Hu, Y.; Wen, J. Assessing the Freeze–Thaw Dynamics with the Diurnal Amplitude Variations Algorithm Utilizing NEON Soil Temperature Profiles. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 7904–7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, S.E.; Jacobs, J.M. Enhanced Identification of Snow Melt and Refreeze Events From Passive Microwave Brightness Temperature Using Air Temperature. Water Resour. Res. 2019, 55, 3248–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vant, M.R.; Ramseier, R.O.; Makios, V. The complex-dielectric constant of sea ice at frequencies in the range 0.1–40 GHz. J. Appl. Phys. 1978, 49, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entekhabi, D.; Njoku, E.G.; O’Neill, P.E.; Kellogg, K.H.; Crow, W.T.; Edelstein, W.N.; Entin, J.K.; Goodman, S.D.; Jackson, T.J.; Johnson, J.; et al. The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) Mission. Proc. IEEE 2010, 98, 704–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Dunbar, R.S.; Derksen, C.; Colliander, A.; Kim, Y.; Kimball, J.S. SMAP L3 Radiometer Global and Northern Hemisphere Daily 36 km EASE-Grid Freeze/Thaw State; Version 3; NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2020. Available online: https://nsidc.org/sites/default/files/spl3ftp-v003-userguide_0.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- Dunbar, S.; Xu, X.; Colliander, A.; Derksen, C.; Kimball, J.; Kim, Y. Algorithm Theoretical Basis Document (ATBD) SMAP Level 3 Radiometer Freeze/Thaw Data Products (L3_FT_P and L3_FT_P_E); California Institute of Technology: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, W.M.; Tonboe, R.T.; Stroeve, J. Mapping of sea ice in 1975 and 1976 using the NIMBUS-6 Scanning Microwave Spectrometer (SCAMS). Remote Sens. Environ. 2025, 328, 114815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, W.M.; Tonboe, R.T.; Stroeve, J. Mapping of sea ice concentration using the NASA NIMBUS 5 Electrically Scanning Microwave Radiometer data from 1972–1977. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1940 to Present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) [Data Set] 2023. Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-single-levels?tab=overview (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- DiGirolamo, N.; Parkinson, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Gloersen, P.; Zwally, H. Sea Ice Concentrations from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS Passive Microwave Data, Version 2; NASA National Snow and Ice Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center: Boulder, CO, USA, 2022.

- Comiso, J.C.; Meier, W.N.; Gersten, R. Variability and trends in the A rctic S ea ice cover: Results from different techniques. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 6883–6900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Eisenman, I. Observed Antarctic sea ice expansion reproduced in a climate model after correcting biases in sea ice drift velocity. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alekseeva, T.; Tikhonov, V.; Frolov, S.; Repina, I.; Raev, M.; Sokolova, J.; Sharkov, E.; Afanasieva, E.; Serovetnikov, S. Comparison of Arctic Sea Ice concentrations from the NASA team, ASI, and VASIA2 algorithms with summer and winter ship data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, H.-C. Evaluation of summer passive microwave sea ice concentrations in the Chukchi Sea based on KOMPSAT-5 SAR and numerical weather prediction data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 209, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, J.; Delamere, J.; Heil, P. The Ice Watch Manual; University of Alaska Fairbanks: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2020; Available online: https://cryo.met.no/en/icewatch (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Beitsch, A.; Kern, S.; Kaleschke, L. Comparison of SSM/I and AMSR-E Sea Ice Concentrations with ASPeCt Ship Observations Around Antarctica. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 1985–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arctic Ocean—High Resolution Sea Ice Information L4. E.U. Copernicus Marine Service Information (CMEMS). Marine Data Store (MDS). Available online: https://data.marine.copernicus.eu/product/SEAICE_ARC_PHY_AUTO_L4_MYNRT_011_024/description (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Cavalieri, D.J.; Parkinson, C.L.; Gloersen, P.; Comiso, J.C.; Zwally, H.J. Deriving long-term time series of sea ice cover from satellite passive-microwave multisensor data sets. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1999, 104, 15803–15814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaß, N.; Kaleschke, L. Improving passive microwave sea ice concentration algorithms for coastal areas: Applications to the Baltic Sea. Tellus A 2010, 62, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narumalani, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jensen, J.R. Application of remote sensing and geographic information systems to the delineation and analysis of riparian buffer zones. Aquat. Bot. 1997, 58, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reul, N.; Tenerelli, J.; Chapron, B.; Vandemark, D.; Quilfen, Y.; Kerr, Y. SMOS satellite L-band radiometer: A new capability for ocean surface remote sensing in hurricanes. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2012, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, K.R.; Elachi, C.; Ulaby, F.T. Microwave remote sensing from space. Proc. IEEE 2005, 73, 970–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Vihma, T.; Zhou, M.; Yu, L.; Uotila, P.; Sein, D.V. Impacts of strong wind events on sea ice and water mass properties in Antarctic coastal polynyas. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 3505–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Q.; Wang, K. Recent changes in pan-Antarctic region surface snowmelt detected by AMSR-E and AMSR2. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 3811–3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, S.; Liang, Q.; Wang, K. Global snowmelt onset reflects climate variability: Insights from spaceborne radiometer observations. J. Clim. 2022, 35, 2945–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkynen, M.; Similä, M. AMSR2 Thin Ice Detection Algorithm for the Arctic Winter Conditions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 4303718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Product | Spatial Resolution | Primary Role in This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core input | |||

| L-band TB (Twice a day for high-latitude areas) | SMAP SPL3FTP (Version 3) | 36 km | Primary input for SIC retrieval and DAV calculation. |

| Constraint & Endmember definition | |||

| ERA5 SIC, SST, IST (Hourly) | ERA5 (ECMWF) | 0.25° | Define pure water (SIC = 0%) and pure ice (SIC = 100%) endmember regions; quantify impacts of warm water (SST) and extremely low temperature conditions of ice (0–7 cm layer ice temperature). |

| Reference for optimization and evaluation | |||

| SSM/I SIC (Daily) | SSM/I-SSMIS (NASA Team, Version 2) | 25 km | Primary reference for algorithm threshold determination, optimization, and performance evaluation. |

| Independent validation | |||

| Ship-based SIC(Hourly) | ICEWatch/ASSIST Program | Point observation | In situ validation source. |

| SAR SIC (Daily) | Arctic Ocean—High Resolution Sea Ice Information L4 | 1 km | High-resolution reference for validation. |

| Group | Δμ (K) | RSD (Seawater) | RSD (Sea Ice) | CNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBH | 155.98 | 10.09 | 5.76 | 10.00 |

| PD | 24.13 | 3.51 | 24.11 | 6.51 |

| PR | 0.30 | 6.06 | 33.33 | 13.42 |

| Group | Δμ (K) | RSD (Seawater) | RSD (Sea Ice) | CNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBH | 160 | 1.62 | 2.78 | 23.94 |

| PD | 24.77 | 1.86 | 20.24 | 8.54 |

| PR | 0.31 | 2.94 | 33.33 | 21.93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; Lv, S.; Li, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, J. A New Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) Retrieval Algorithm for Spaceborne L-Band Brightness Temperature (TB) Data. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020265

Hu Y, Lv S, Li Z, Zeng Y, Li X, Zhang Y, Wen J. A New Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) Retrieval Algorithm for Spaceborne L-Band Brightness Temperature (TB) Data. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(2):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020265

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Yin, Shaoning Lv, Zhijin Li, Yijian Zeng, Xiehui Li, Yijun Zhang, and Jun Wen. 2026. "A New Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) Retrieval Algorithm for Spaceborne L-Band Brightness Temperature (TB) Data" Remote Sensing 18, no. 2: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020265

APA StyleHu, Y., Lv, S., Li, Z., Zeng, Y., Li, X., Zhang, Y., & Wen, J. (2026). A New Sea Ice Concentration (SIC) Retrieval Algorithm for Spaceborne L-Band Brightness Temperature (TB) Data. Remote Sensing, 18(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18020265