Spectral Characterization of Nine Urban Tree Species in Southern Wisconsin

Highlights

- Incorporating first derivatives of hyperspectral data and vegetation indices in a random forest model achieved the highest predictive performance (80.4%).

- The red-edge and shortwave infrared 1 (SWIR 1) regions provided the most influential variables for the random forest classification.

- While hyperspectral reflectance features aid species discrimination, they do not capture all variability, and adding non-spectral variables may improve accuracy.

- Targeted reductions—such as excluding spectral reflectance when first derivatives and vegetation indices already capture key variation—may improve accuracy and reduce computational cost.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

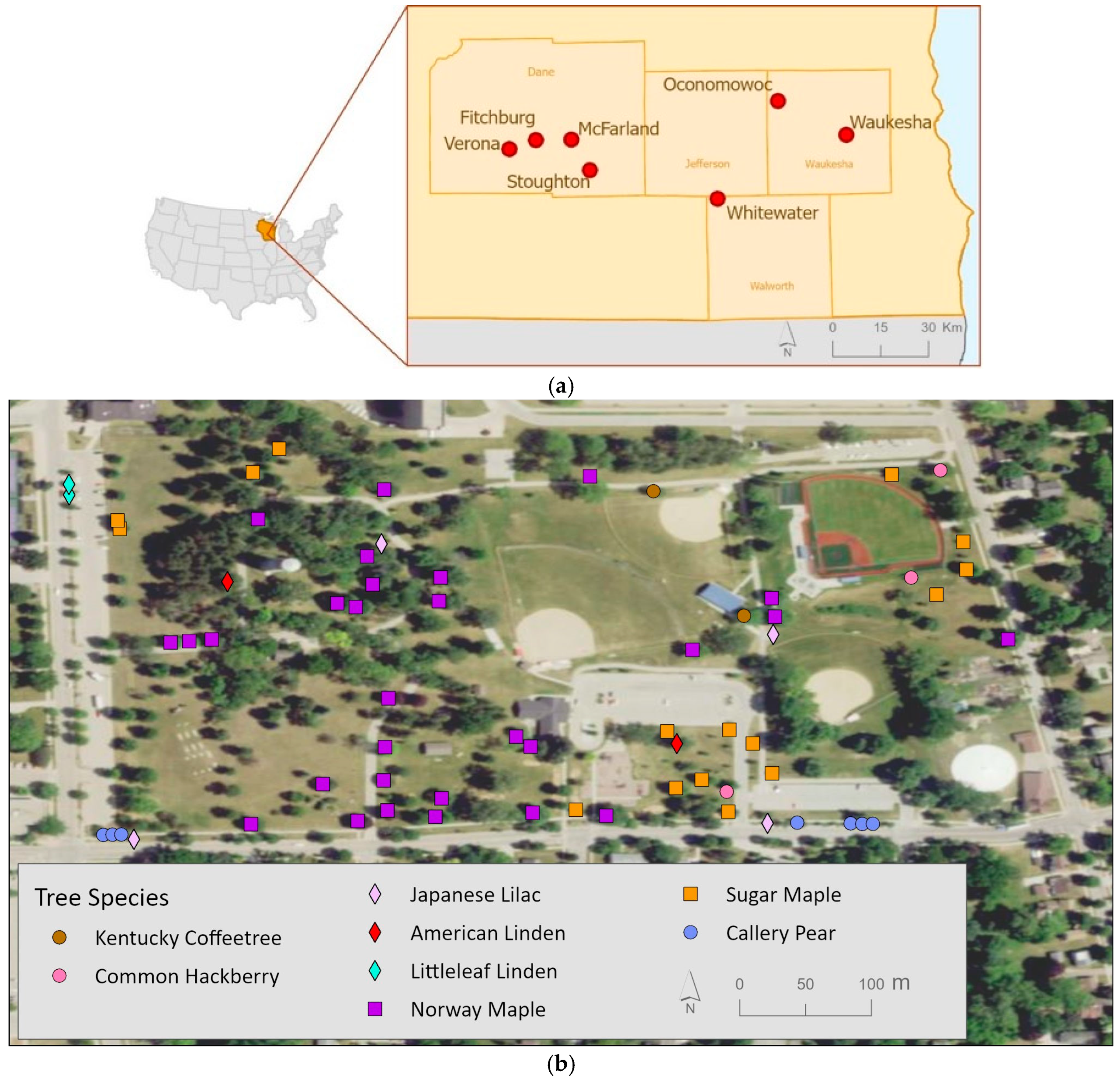

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Field Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.3. Spectral Features Extraction and Selection

2.4. Random Forest and Accuracy Assessment

3. Results

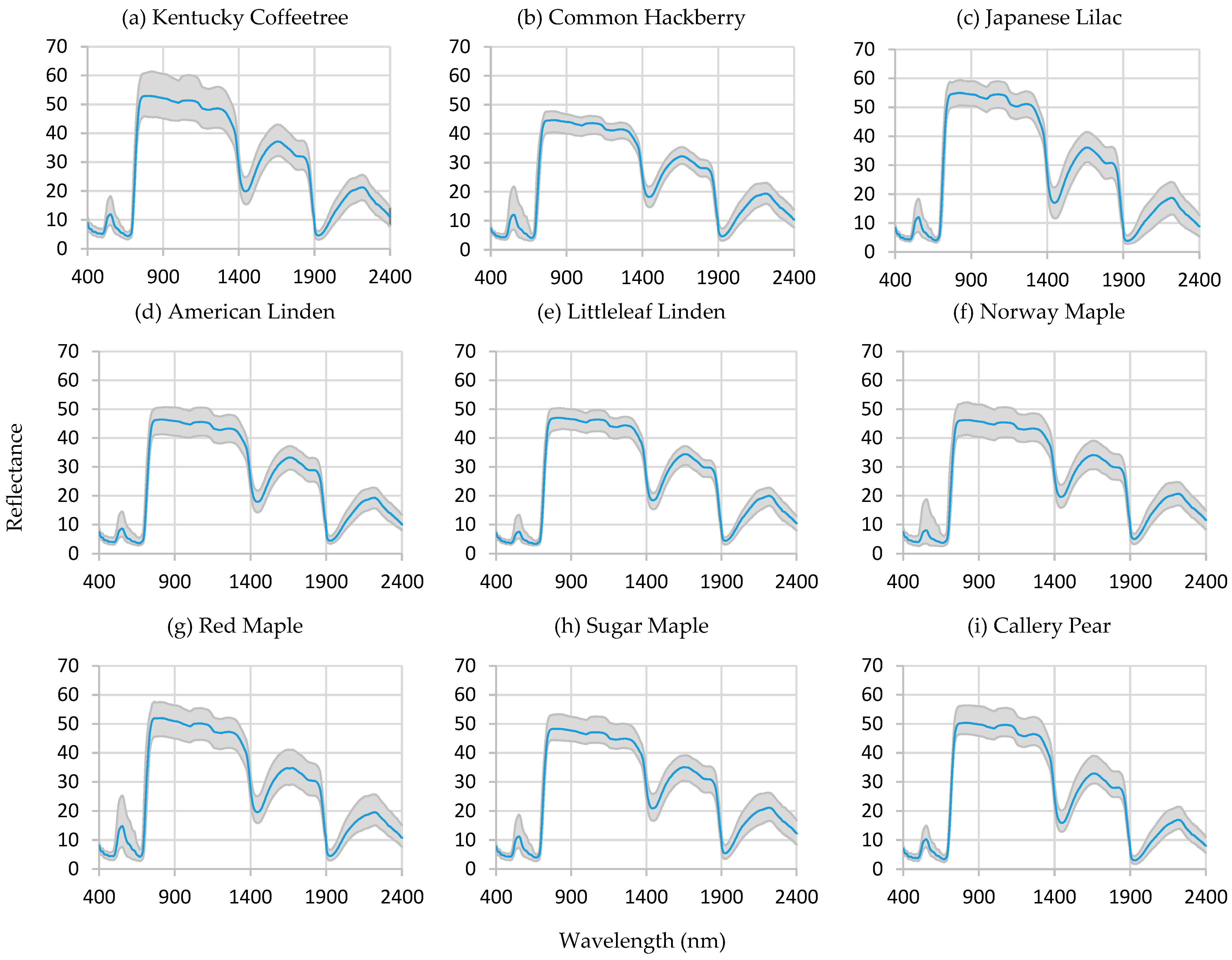

3.1. Spectral Reflectance

3.2. Vegetation Indices

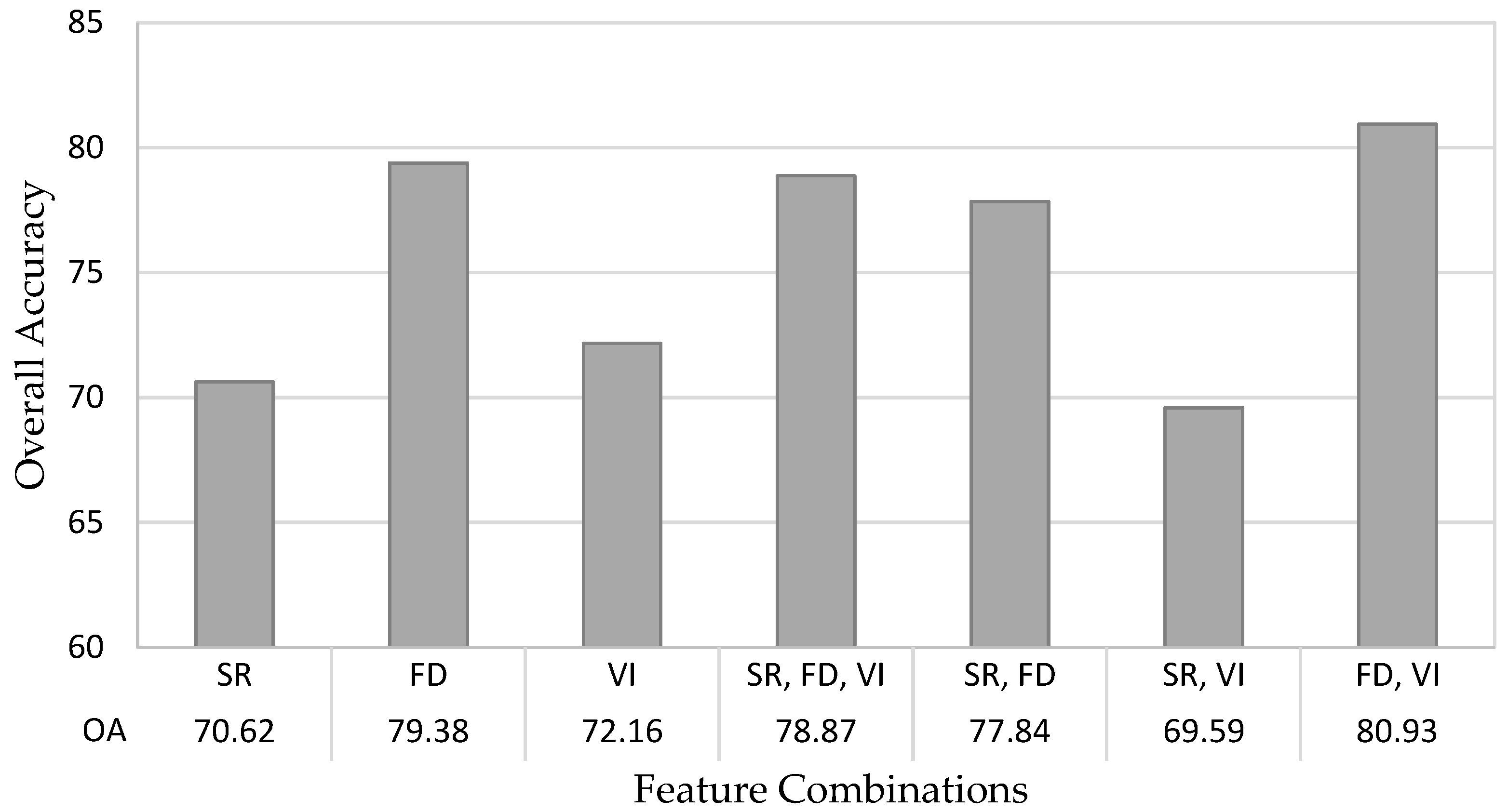

3.3. Random Forest Accuracy

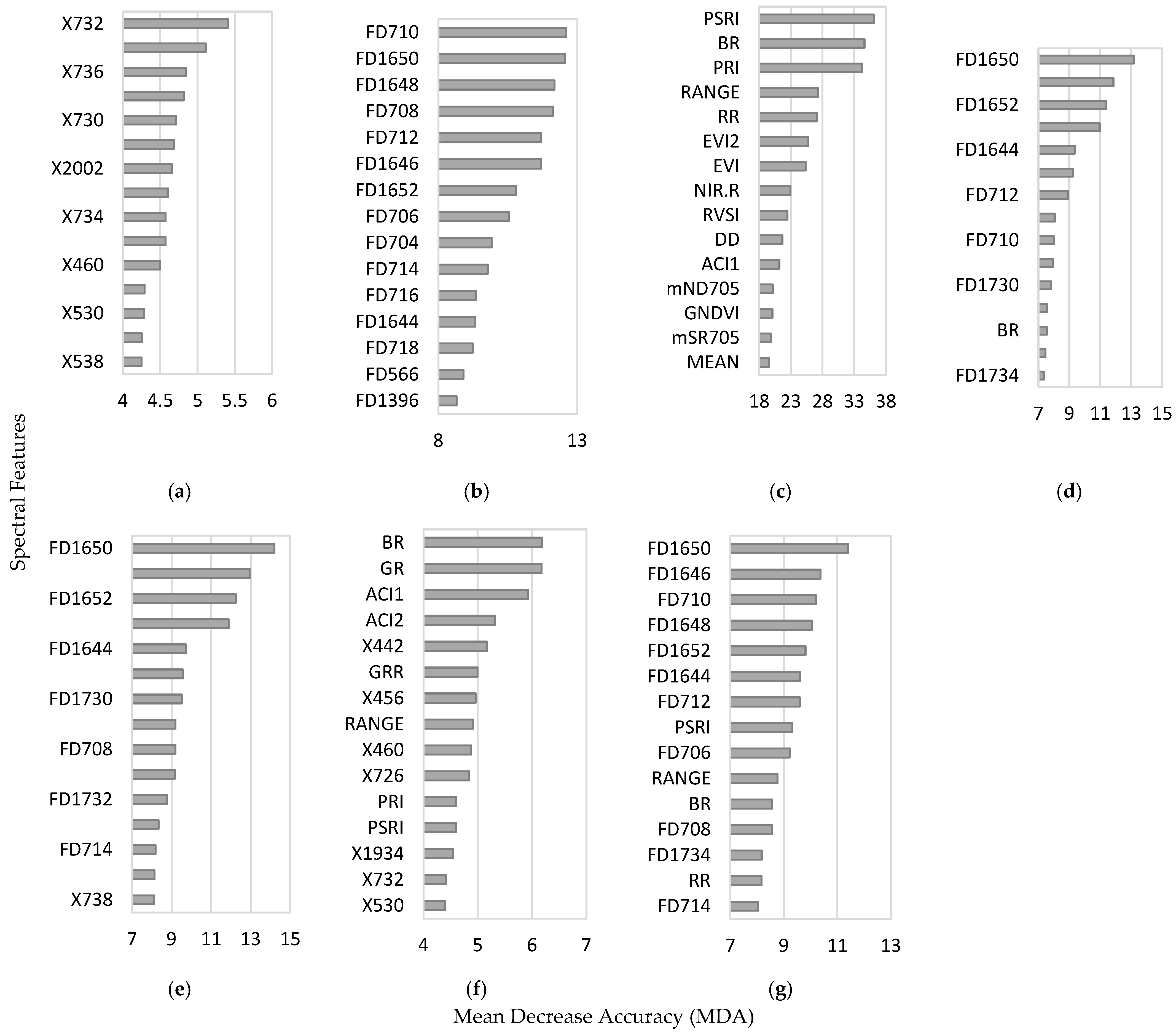

3.4. Variable of Importance

4. Discussion

4.1. On the Spectral Curves

4.2. On the Features of Random Forest Models

4.3. On the Accuracy of Leaf Level Classification

4.4. On Species-Specific Classification Performance

4.5. On the Variables of Importance

4.6. Generality, Limitations, and Recommendations for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACI1 | Anthocyanin content index I |

| ACI2 | Anthocyanin content index II |

| AL | American linden |

| ARVI | Atmospherically resistant vegetation index |

| AVIRIS | Airborne visible/infrared imaging spectrometer |

| AVIRIS-NG | AVIRIS-next generation |

| BDD | Backward divided difference |

| BR | Blue ratio |

| CART | Classification and regression trees |

| CDA | Canonical discriminant analysis |

| CH | Common hackberry |

| CI1 | Chlorophyll index I |

| CI2 | Chlorophyll index II |

| CP | Callery pear |

| DBH | Diameter at breast height |

| DD | Double difference vegetation index |

| EO | Earth observing |

| EVI | Enhanced vegetation index |

| EVI2 | 2-band enhanced vegetation index |

| FD | First derivative |

| GARI | Green atmospherically resistant vegetation index |

| GNDVI | Green normalized difference vegetation index |

| GR | Green ratio |

| GRR | Green-red difference index |

| IPVI | Infrared percentage vegetation index |

| JL | Japanese lilac |

| KC | Kentucky coffeetree |

| KNN | K-nearest neighbor |

| LC-RP Pro | Leaf clip and reflectance probe |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| LL | Littleleaf linden |

| MDA | Mean decrease in accuracy |

| MEAN | Average reflectance between 690 nm and 740 nm |

| MEDI | Median reflectance between 690 nm and 740 nm |

| mND705 | Modified normalized difference index |

| MNF | Minimum noise fraction |

| MSI | Multispectral instrument |

| mSR705 | Modified simple ratio |

| NDRE | Normalized difference red-edge index |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| NIR-R | Infrared–Red Difference index |

| NM | Norway maple |

| OA | Overall accuracy |

| OOB | Out-of-bag |

| PA | Producer’s accuracy |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PRI | Photochemical reflectance index |

| PRISMA | PRecursore IperSpettrale della Missione Applicativa |

| PSI | Plant stress index |

| PSRI | Plant senescence reflectance index |

| PSSR1 | Pigment-specific simple ratio I |

| PSSR2 | Pigment-specific simple ratio II |

| R1 | Ratio vegetation stress index I |

| R2 | Ratio vegetation stress index II |

| R3 | Ratio vegetation stress index III |

| RENVI | Red-edge normalized difference vegetation index |

| RF | Random forest |

| RM | Red maple |

| RR | Red ratio |

| RVI | Ratio vegetation index |

| RVSI | Red-edge vegetation stress index |

| SM | Sugar maple |

| SR | Spectral reflectance |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| SWIR | Shortwave infrared |

| UA | User’s accuracy |

| UAVs | Unmanned aerial vehicles |

| VARI | Visible atmospherically resistant index |

| VI | Vegetation indices |

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; (ST/ESA/SER.A/420); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/assets/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Rasoolzadeh, R.; Mobarghaee Dinan, N.; Esmaeilzadeh, H.; Rashidi, Y.; Sadeghi, S.M.M. Assessment of air pollution removal by urban trees based on the i-Tree Eco Model: The case of Tehran, Iran. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 2142–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, É.; Illés, G.; Borovics, A. Green infrastructure for climate change mitigation: Assessment of carbon sequestration and storage in the urban forests of Budapest, Hungary. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbig, W.; Loheid, S.P.; Schuster, W.; Scharenbroch, B.; Coville, R.; Kruegler, J.; Avery, W.; Haefner, R.; Nowak, D. Quantifying the stormwater runoff volume reduction benefits of urban street tree canopy. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Li, S.; Xing, X.; Zhou, X.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Li, Y. Cooling benefits of urban tree canopy: A systematic review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, G.S.; Quinn, J.W.; Neckerman, K.M.; Perzanowski, M.S.; Rundle, A. Children living in areas with more street trees have lower prevalence of asthma. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2008, 62, 647–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Xu, W.; Tang, J.; Jiang, X. Correlation analysis of lung cancer and urban spatial factor: Based on survey in Shanghai. J. Thorac. Dis. 2016, 8, 2626–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, D.A.; Vanos, J.K.; Kenny, N.A.; Brown, R.D. The relationship between neighbourhood tree canopy cover and heat-related ambulance calls during extreme heat events in Toronto, Canada. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016, 20, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Sullivan, W.C.; Chang, P.J.; Chang, C.Y. Does awareness affect the restorative function and perception of street trees? Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, K.M.M.; Kaltenbach, A.; Szabo, A.; Bogar, S.; Nieto, F.J.; Malecki, K.M. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental health: Evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 3453–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, G.H.; Michael, Y.L.; Butry, D.T.; Sullivan, A.D.; Chase, J.M. Urban trees and the risk of poor birth outcomes. Health Place 2011, 17, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, A.D.; Unger, D.R.; Parks, C.L. Modeling energy savings from urban shade trees: An assessment of the CITYgreen® energy conservation module. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, R.; Landry, S. A comparative analysis of high spatial resolution IKONOS and WorldView-2 imagery for mapping urban tree species. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 124, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immitzer, M.; Atzberger, C.; Koukal, T. Tree species classification with random forest using very high spatial resolution 8-band WorldView-2 satellite data. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2661–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangi, E.; D’Amico, G.; Francini, S.; Giannetti, F.; Lasserre, B.; Marchetti, M.; Chirici, G. The new hyperspectral satellite PRISMA: Imagery for Forest Types Discrimination. Sensors 2021, 21, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puletti, N.; Camarretta, N.; Corona, P. Evaluating EO1-Hyperion capability for mapping conifer and broadleaved forests. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2016, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hati, J.P.; Samanta, S.; Chaube, N.R.; Misra, A.; Giri, S.; Pramanick, N.; Gupta, K.; Majumdar, S.D.; Chanda, A.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; et al. Mangrove classification using airborne hyperspectral AVIRIS-NG and comparing with other spaceborne hyperspectral and multispectral data. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2021, 24, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramanik, S.; Deep, N.R.; Behera, M.D.; Bhattacharya, B.K.; Dash, J. Species-level classification of mangrove forest using AVIRIS-NG hyperspectral imagery. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 14, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, M.; Roth, K.; Roberts, D. Identifying Santa Barbara’s urban tree species from AVIRIS imagery using canonical discriminant analysis. Remote Sens. Lett. 2013, 4, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, L.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Qi, Y.; Wang, S. UAV hyperspectral remote sensing image classification: A systematic review. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 3099–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, L.E.C.; Sothe, C.; Feitosa, R.Q.; De Almeida, C.M.; Schimalski, M.B.; Borges Oliveira, D.A. Multi-task fully convolutional network for tree species mapping in dense forests using small training hyperspectral data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 179, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Peng, Q.; Wong, M.S.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Ng, K.T.K.; Kwok, C.Y.T.; Hui, K.K.W. Characterizing and classifying urban tree species using bi-monthly terrestrial hyperspectral images in Hong Kong. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 177, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, M.; Bookhagen, B.; Roberts, D.A. Urban tree species mapping using hyperspectral and lidar data fusion. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 14, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, M.; Sugumaran, R. Seasonal effect of tree species classification in an urban environment using hyperspectral data, LiDAR, and an object-oriented approach. Sensors 2008, 8, 3020–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Coops, N.C.; Aven, N.W.; Pang, Y. Mapping urban tree species using integrated airborne hyperspectral and LiDAR remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 200, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yel, S.G.; Tunc Gormus, E. Exploiting hyperspectral and multispectral images in the detection of tree species: A review. Front. Remote Sens. 2023, 4, 1136289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Dai, Z.; Fang, P.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L. A Review: Tree species classification based on remote sensing data and classic deep learning-based methods. Forests 2024, 15, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sothe, C.; Dalponte, M.; Almeida, C.M.d.; Schimalski, M.B.; Lima, C.L.; Liesenberg, V.; Miyoshi, G.T.; Tommaselli, A.M.G. Tree species classification in a highly diverse subtropical forest integrating UAV-based photogrammetric point cloud and hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lu, D.; Li, G.; Chen, E. Classification of land cover, forest, and tree species classes with ZiYuan-3 multispectral and stereo data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, O.; Honkavaara, E.; Tuominen, S.; Viljanen, N.; Hakala, T.; Yu, X.; Hyyppä, J.; Saari, H.; Pölönen, I.; Imai, N.N.; et al. Individual tree detection and classification with UAV-based photogrammetric point clouds and hyperspectral imaging. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabat-Tomala, A.; Raczko, E.; Zagajewski, B. Comparison of support vector machine and random forest algorithms for invasive and expansive species classification using airborne hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/whitewatercitywisconsin,waukeshacitywisconsin,mcfarlandvillagewisconsin,veronacitywisconsin,fitchburgcitywisconsin,WI/PST045221 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Summary of Monthly Normals (1991–2020). Station: Waukesha WWTP, WI. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/services/data/v1?dataset=normals-monthly-1991-2020&startDate=0001-01-01&endDate=9996-12-31&stations=USC00478937&format=pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Didan, K.; Miura, T. Development of a two-band enhanced vegetation index without a blue band. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 112, 3833–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Surfus, J.S. Assessing leaf pigment content and activity with a reflectometer. New Phytol. 1999, 143, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, Y.J.; Tanre, D. Atmospherically resistant vegetation index (ARVI) for EOS-MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1992, 30, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.N. Multi-Temporal Analysis of Community-Scale Vegetation Stress with Imaging Spectroscopy. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Waser, L.T.; Küchler, M.; Jütte, K.; Stampfer, T. Evaluating the potential of WorldView-2 data to classify tree species and different levels of Ash mortality. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 4515–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datt, B. Visible/near-infrared reflectance and chlorophyll content in Eucalyptus leaves. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1999, 20, 2741–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.J. Red and photographic infrared linear combinations for monitoring vegetation. Remote Sens. Environ. 1979, 8, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.D.; Slater, P.N.; Pinter, P.J. Discrimination of growth and water stress in wheat by various vegetation indices through clear and turbid atmospheres. Remote Sens. Environ. 1983, 13, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Q.; Huete, A. A feedback-based modification of the NDVI to minimize canopy background and atmospheric noise. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Merzlyak, M.N. Use of a green channel in remote sensing of global vegetation from EOS-MODIS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Signature analysis of leaf reflectance spectra: Algorithm development for remote sensing of chlorophyll. J. Plant Physiol. 1996, 148, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel, M.F.; Chamard, P.C.; Guenegou, M.; Lerhun, J.; Levasseur, J.; Togola, M. Utilisation des bandes spectrales du vert et du rouge pour une meilleure évaluation des formations végétales actives. In Télédétection et Cartographie; AUPELF-UREF: Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 1991; pp. 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Crippen, R. Calculating the vegetation index faster. Remote Sens. Environ. 1990, 34, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, D.A.; Gamon, J.A. Relationships between leaf pigment content and spectral reflectance across a wide range of species, leaf structures and developmental stages. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 81, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.M.; Clarke, T.R.; Richards, S.E.; Colaizzi, P.D.; Haberland, J.; Kostrzewski, M.; Waller, P.; Choi, C.; Riley, E.; Thompson, T.; et al. Coincident detection of crop water stress, nitrogen status, and canopy density using ground-based multispectral data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Precision Agriculture, Bloomington, MN, USA, 16–19 July 2000; Available online: https://www.tucson.ars.ag.gov/unit/publications/PDFfiles/1356.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Rouse, J.; Haas, R.; Schell, J.; Deering, D. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. In Proceedings of the Goddard Space Flight Center 3d ERTS-1 Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 10–14 December 1973; NASA: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 1974; Volume 1, pp. 309–317. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19740022614.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Gamon, J.A.; Serrano, L.; Surfus, J.S. The photochemical reflectance index: An optical indicator of photosynthetic radiation use efficiency across species, functional types, and nutrient levels. Oecologia 1997, 112, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamon, J.A.; Peñuelas, J.; Field, C.B. A narrow-waveband spectral index that tracks diurnal changes in photosynthetic efficiency. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 41, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, G.A. Quantifying chlorophylls and carotenoids at leaf and canopy scales: An evaluation of some hyperspectral approaches. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 66, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Rakitin, V.Y. Non-destructive optical detection of pigment changes during leaf senescence and fruit ripening. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 106, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.A.; Miller, R.L. Early detection of plant stress by digital imaging within narrow stress-sensitive wavebands. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 50, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, C.F. Derivation of leaf area index from quality of light on the forest floor. Ecology 1969, 50, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.; Merzlyak, M.N. Spectral reflectance changes associated with autumn senescence of Aesculus hippocastanum L. and Acer platanoides L. leaves. Spectral features and relation to chlorophyll estimation. J. Plant Physiol. 1994, 143, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitelson, A.A.; Kaufman, Y.J.; Stark, R.; Rundquist, D. Novel algorithms for remote estimation of vegetation fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 80, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.L.; Roberts, D.A. Species-level differences in hyperspectral metrics among tropical rainforest trees as determined by a tree-based classifier. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 1820–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschler, J.; Atzberger, C.; Immitzer, M. Individual tree crown segmentation and classification of 13 tree species using airborne hyperspectral data. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozgeris, G.; Juodkienė, V.; Jonikavičius, D.; Straigytė, L.; Gadal, S.; Ouerghemmi, W. Ultra-light aircraft-based hyperspectral and colour-infrared imaging to identify deciduous tree species in an urban environment. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Leng, W.; Liu, K.; Liu, L.; He, Z.; Zhu, Y. Object-based mangrove species classification using unmanned aerial vehicle hyperspectral images and digital surface models. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquemoud, S.; Ustin, S.L. Leaf Optical Properties: A Handbook of Practical and Theoretical Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brabant, C.; Alvarez-Vanhard, E.; Laribi, A.; Morin, G.; Thanh Nguyen, K.; Thomas, A.; Houet, T. Comparison of Hyperspectral Techniques for Urban Tree Diversity Classification. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, O.; Skidmore, A.K. Red-edge shift and biochemical content in grass canopies. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2007, 62, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalponte, M.; Ørka, H.O.; Gobakken, T.; Gianelle, D.; Næsset, E. Tree Species Classification in Boreal Forests with Hyperspectral Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 2632–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Skidmore, A.K.; Wang, T.; Holzwarth, S.; Heiden, U.; Pinnel, N.; Zhu, X.; Heurich, M. Tree species classification using plant functional traits from LiDAR and hyperspectral data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2018, 73, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartling, S.; Sagan, V.; Maimaitijiang, M. Urban tree species classification using UAV-based multi-sensor data fusion and machine learning. GIScience Remote Sens. 2021, 58, 1250–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Common Name | Abbreviation | Scientific Name | Trees Sampled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kentucky Coffeetree | KC | Gymnocladus dioica | 57 |

| Common Hackberry | CH | Celtis occidentalis | 55 |

| Japanese Lilac | JL | Syringa reticulata | 82 |

| American Linden | AL | Tilia americana | 85 |

| Littleleaf Linden | LL | Tilia Cordata | 73 |

| Norway Maple | NM | Acer platanoides | 91 |

| Red Maple | RM | Acer rubrum | 70 |

| Sugar Maple | SM | Acer saccharum | 75 |

| Callery Pear | CP | Pyrus calleryana | 73 |

| Spectral Index | Formula | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 2-Band Enhanced Vegetation Index | [34] | |

| Anthocyanin Content Index I | [35] | |

| Anthocyanin Content Index II | [35] | |

| Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index | [36] | |

| Average Reflectance Between 690 nm and 740 nm | [37] | |

| Blue Ratio | [38] | |

| Chlorophyll Index I | [39] | |

| Chlorophyll Index II | [39] | |

| Infrared–Red Difference Index | [40] | |

| Double Difference Vegetation Index | [41] | |

| Enhanced Vegetation Index | [42] | |

| Green Atmospherically Resistant Vegetation Index | [43] | |

| Green Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [44] | |

| Green Ratio | [38] | |

| Green-Red Difference Index | [45] | |

| Infrared Percentage Vegetation Index | [46] | |

| Median Reflectance between 690 nm and 740 nm | [37] | |

| Modified Normalized Difference Index | [47] | |

| Modified Simple Ratio | [47] | |

| Normalized Difference Red-Edge Index | [48] | |

| Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [49] | |

| Photochemical Reflectance Index | [50,51] | |

| Pigment Specific Simple Ratio I | [52] | |

| Pigment Specific Simple Ratio II | [52] | |

| Plant Senescence Reflectance Index | [53] | |

| Plant Stress Index | [54] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Index | [55] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Stress Index I | [54] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Stress Index II | [54] | |

| Ratio Vegetation Stress Index III | [54] | |

| Red-Edge Normalized Difference Vegetation Index | [56] | |

| Red-edge Vegetation Stress Index | [37] | |

| Red Ratio | [38] | |

| Reflectance Range between 690 nm and 740 nm | [37] | |

| Visible Atmospherically Resistant Index | [57] |

| Model Features | Model Designation | Number of Features |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral reflectance | SR | 977 |

| First derivative | FD | 976 |

| Vegetation indices | VI | 35 |

| Spectral reflectance, first derivative, vegetation indices | SR-FD-VI | 1988 |

| Spectral reflectance, first derivative | SR-FD | 1953 |

| Spectral reflectance, vegetation indices | SR-VI | 1012 |

| First derivative, vegetation indices | FD-VI | 1011 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 85.7 |

| CH | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 71.4 |

| AL | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 55.6 |

| JL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 82.1 |

| LL | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 68.4 |

| NM | 0 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 34 | 61.8 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 91.7 |

| SM | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 15 | 1 | 23 | 65.2 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 17 | 23 | 73.9 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 70.6 | 62.5 | 60.0 | 95.8 | 61.9 | 77.8 | 52.4 | 68.2 | 81.0 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 100 |

| CH | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 78.6 |

| AL | 0 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 27 | 66.7 |

| JL | 4 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 28 | 82.1 |

| LL | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 73.3 |

| NM | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 22 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 32 | 68.8 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 95.5 |

| SM | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 20 | 85.0 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 24 | 79.2 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 70.6 | 68.8 | 72.0 | 95.8 | 52.4 | 81.5 | 100 | 77.3 | 90.5 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 94.1 |

| CH | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 81.3 |

| AL | 0 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 23 | 65.2 |

| JL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 26 | 84.6 |

| LL | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 68.4 |

| NM | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 34 | 73.5 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 81.3 |

| SM | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 24 | 70.8 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 19 | 84.2 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 94.1 | 81.3 | 60.0 | 91.7 | 61.9 | 92.6 | 61.9 | 77.3 | 76.2 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 13 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 15 | 86.7 |

| CH | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 76.9 |

| AL | 0 | 2 | 17 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 65.4 |

| JL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 88.0 |

| LL | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 76.5 |

| NM | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 65.7 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 95.0 |

| SM | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 21 | 76.2 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 22 | 86.4 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 76.5 | 62.5 | 68.0 | 91.7 | 61.9 | 85.2 | 90.5 | 72.7 | 90.5 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 87.5 |

| CH | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 76.9 |

| AL | 0 | 2 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 24 | 62.5 |

| JL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 88.0 |

| LL | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 68.4 |

| NM | 0 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 36 | 63.9 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 95.0 |

| SM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 0 | 19 | 84.2 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 22 | 86.4 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 82.4 | 62.5 | 60.0 | 91.7 | 61.9 | 85.2 | 90.5 | 72.7 | 90.5 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 13 | 84.6 |

| CH | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 78.6 |

| AL | 1 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 27 | 55.6 |

| JL | 2 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 28 | 78.6 |

| LL | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 65.0 |

| NM | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 33 | 66.7 |

| RM | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 83.3 |

| SM | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 15 | 0 | 24 | 62.5 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 17 | 23 | 73.9 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 64.7 | 68.8 | 60.0 | 91.7 | 61.9 | 81.5 | 47.6 | 68.2 | 81.0 |

| KC | CH | AL | JL | LL | NM | RM | SM | CP | Total | UA% | |

| KC | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1.00 |

| CH | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 84.6 |

| AL | 0 | 2 | 18 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 28 | 64.3 |

| JL | 4 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 28 | 82.1 |

| LL | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 84.6 |

| NM | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 24 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 68.6 |

| RM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 22 | 95.5 |

| SM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 19 | 89.5 |

| CP | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 24 | 79.2 |

| Total | 17 | 16 | 25 | 24 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 194 | |

| PA% | 70.6 | 68.8 | 72.0 | 95.8 | 52.4 | 88.9 | 1.00 | 77.3 | 90.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Duchesne, R.R.; Krebs, A.; Seuser, M. Spectral Characterization of Nine Urban Tree Species in Southern Wisconsin. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010099

Duchesne RR, Krebs A, Seuser M. Spectral Characterization of Nine Urban Tree Species in Southern Wisconsin. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuchesne, Rocio R., Alex Krebs, and Madelyn Seuser. 2026. "Spectral Characterization of Nine Urban Tree Species in Southern Wisconsin" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010099

APA StyleDuchesne, R. R., Krebs, A., & Seuser, M. (2026). Spectral Characterization of Nine Urban Tree Species in Southern Wisconsin. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010099