1. Introduction

Nowadays, coastal areas are vulnerable environments typically subject to nourishing procedures, breakwaters, groins, or nature-based reef solutions to mitigate the shoreline retreat. Performing a coastal survey means dealing with a dynamic environment that can, at the same time, be threatened by sea storms and flood risk. This context highlights the need to establish a monitoring procedure [

1] that maintains adequate accuracy in relation to the phenomena to be observed, while also being rapid, flexible, and applicable even after extreme weather events that may have drastically changed the scenario.

In this context, the widespread use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for small and medium extent territorial surveys [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] is related primarily to their flexibility in terms of object scale and survey goals, providing high spatial and temporal resolution while being more time and cost effective than airborne-based [

7,

8,

9,

10] or ground-based solutions [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. A UAV system can be equipped with different sensors [

17]: an RGB camera and LiDAR (light detection and ranging) sensor are both able to capture the object geometry. Moreover, the LiDAR survey and processing are usually faster than the one performed by photogrammetry with an RGB camera, and they also benefit from the LiDAR sensor’s ability to penetrate the canopy and collect ground points thanks to the multi-echo technology. Whereas using direct georeferencing for the RGB camera is not mandatory and can lead to vertical bias due to incorrect sensor calibration [

18], direct georeferencing is mandatory for the LiDAR survey and processing. In other words, integrating and optimizing the GNSS (global navigation satellite system) and IMU (inertial measurement unit) data collected by the vehicle during flight provides accurate position and attitude information to the range data collected by the laser-scanning mechanism [

19,

20]. Specifically, GNSS data can be retrieved using relative positioning techniques [

21,

22,

23,

24], which are based on computing the baseline vector between the master station, with well-known coordinates, and the rover device. While post-processed kinematic (PPK) procedures compute the trajectory afterwards, real-time kinematic (RTK) and network real-time kinematic (NRTK) are real-time correction modes that use, respectively, a remote master station or data provided by a network of remote stations (e.g., the nearest station or a virtual reference station—VRS).

A great number of studies have investigated the potential and limitations of UAV-RGB surveys, evaluating the influence of flight patterns [

25,

26] or the integration of accurate camera locations [

27,

28,

29], to minimize the use of GCPs (ground control points) and enhance the final output. Instead, less research has focused on the accuracy of UAV-LiDAR surveying and processing, despite the commercialization in recent years of consumer-grade UAV-LiDAR systems, which has progressively increased their use. In this context, the following studies need to be highlighted:

Kamp et al. [

30] evaluated the uncertainties linked to airborne and UAV-based LiDAR surveys. They focused on the relative reconstruction, examining how system, flight, processing, and site characteristics affect the reconstruction and emphasizing the importance of accounting for these uncertainties to avoid incorrect change-detection estimates in multi-epoch surveys.

Bartmiński et al. [

31] evaluated the repeatability of final digital terrain models (DTMs) produced using different UAV-LiDAR systems. However, the impact of trajectory correction was not considered in their comparison.

Mandlburger et al. [

32] compared the performance of a survey-grade UAV-LiDAR system with that of a consumer-grade system (i.e., the DJI “Zenmuse L1”). They also attempted to improve strip adjustment using alternative methods compared with the optimization implemented in the proprietary software.

Pöppl et al. [

33] proposed a novel approach for LiDAR processing (airborne- or UAV-based), integrating plane-based LiDAR features with raw IMU data and pre-processed GNSS data, optionally allowing the joint processing of multiple dataset. This approach is presented as an alternative to the standard procedure, which consists of an initial Kalman filter-based integration of GNSS/IMU data followed by strip adjustment.

Kersten et al. [

34] investigated the accuracy of the DJI “Matrice 300 RTK” vehicle equipped with both the DJI “Zenmuse P1” and “Zenmuse L1” sensors, using different flight and scanning configurations.

Štroner et al. [

35] analyzed the accuracy of a UAV-LiDAR point cloud using highly reflective targets. They subsequently attempted to reduce georeferencing errors using different types of transformations (translation or roto-translation).

Dreier et al. [

36] investigated the quality of UAV-LiDAR point clouds in terms of noise, precision, accuracy, and the influence of the reference base station used.

Cao et al. [

37] proposed a method for integrating UAV-LiDAR and USV-SBES (unmanned surface vehicle—single beam echosounder) data to produce a continuous topo-bathymetric model, then analyzing its accuracy along GNSS transects.

The common ground among these studies is the limited possibility for quality control [

38] of LiDAR data processing and outputs. Photogrammetric processing is inherently redundant because it relies on homologous points and typically integrates absolute measurements (e.g., GCPs or capture locations). In contrast, LiDAR data lack inherent redundancy, and the error associated with each measurement depends on an error budget related to the complexity of the system (GNSS, IMU, LiDAR) [

39]. All these works present different approaches and perspectives for evaluating the performance of UAV-LiDAR systems. However, in most cases, the base station used for trajectory estimation is not explicitly described, even though it can strongly influence the results.

Although real-time GNSS corrections help maintain the planned flight trajectory, the corresponding positional data are generally not recommended for final processing due to potential temporary signal outages or degradations during the survey. Alternatively, trajectory post-processing can be performed using GNSS observations acquired from temporary, virtual, or permanent stations. Given these alternatives, this work aims to quantify how the GNSS base station type (temporary, permanent, or VRS) and its distance from the survey site affect UAV-LiDAR direct georeferencing accuracy, and to assess whether integrating vertical ground control points (vGCPs) can mitigate vertical errors induced by suboptimal base stations. The comparison is carried out both on the estimated trajectories and on the final outputs. In this way, it is possible to evaluate how trajectory miscalculations can lead to accuracy loss by comparing the LiDAR-derived digital terrain model (DTM) with reference data (target network or photogrammetric digital surface model—DSM). Statistical and spatial analyses of the differences are performed using custom QGIS tools developed for this study that allow simpler and faster comparisons between targets, DEMs (digital elevation models), and SBET (smoothed best estimate of trajectory) files. These tests are conducted in a specific study area: a coastal environment that is periodically monitored. Their evaluation makes it possible to identify the best solution for preserving both the relative and absolute reconstruction of the model, while also highlighting possible alternative approaches along with their expected uncertainties. Although this research is based on a specific case study and the results cannot be valid for all possible situations, these tests contribute to providing a clearer overview of the options available to users performing this type of processing with a consumer-grade UAV system and closed-source proprietary software.

In the following sections, the survey and processing steps are first documented (

Section 2), followed by an overview of the test results (

Section 3) and a discussion of these results (

Section 4), highlighting the main strengths and limitations of each station type used in this study site.

2. Materials and Methods

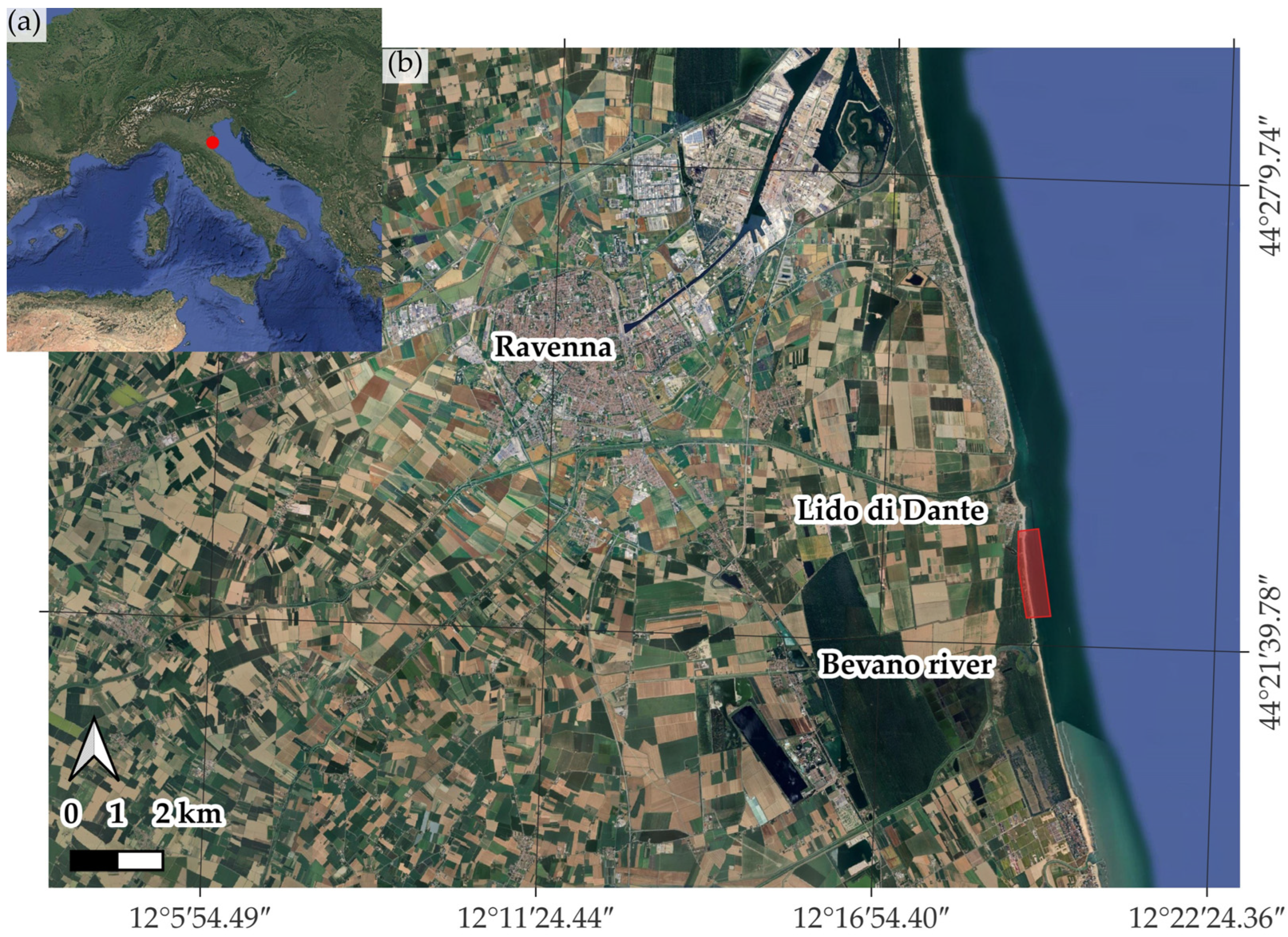

2.1. Study Site

The data used in this work were collected in a coastal area near the mouth of the Bevano River (Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy). This area is part of a nature reserve that, like the entire Adriatic coast in the Emilia-Romagna region [

40,

41,

42], is threatened by coastal erosion and flooding, and has been designated as the study area (

Figure 1) for the European project “LIFE NatuReef” [

43]. The goal of this project is to restore biogenic reefs, specifically using oysters (

Ostrea edulis) and sabellariid worms (

Sabellaria spinulosa), to both mitigate coastal erosion and enhance the marine ecosystem.

2.2. Ground Control Points Collection

To be used as ground control points (GCPs) for photogrammetric processing, 18 targets (

Figure 2) were distributed across the survey area in a homogeneous and redundant manner. In cases where morphological constraints or vegetation obstruction prevented the placement of circular plywood targets (diameter of 50 cm, with a black and white pattern), alternative solutions such as pins or square plastic targets (10 × 10 cm, with a black and white pattern) were employed on top of available wooden elements. The pins were permanently installed to serve as reference points for future monitoring purposes.

The positions of the targets were measured using a STONEX “S900A” GNSS receiver in NRTK-VRS mode [

44]. Each solution was averaged over 60 epochs with an assigned precision assessment: the final solutions have an average and maximum horizontal standard deviation (SD) of respectively 0.7 cm and 1.2 cm, and an average and maximum vertical SD of respectively 0.9 cm and 1.2 cm. The collected target coordinates, framed in the official Italian reference system RDN2008, are projected in UTM zone 33, and the orthometric heights are computed using the software ConvER2021 [

45] and the geoid model ITALGEO2005 [

46]. It is important to underline that further processing and comparison between the GNSS data and UAV data are conducted within the projected cartographic system while retaining the ellipsoidal height. This approach ensures compatibility across datasets from different sources. When required, final outputs can be shifted by applying the estimated mean geoid undulation of approximately 39.04 m.

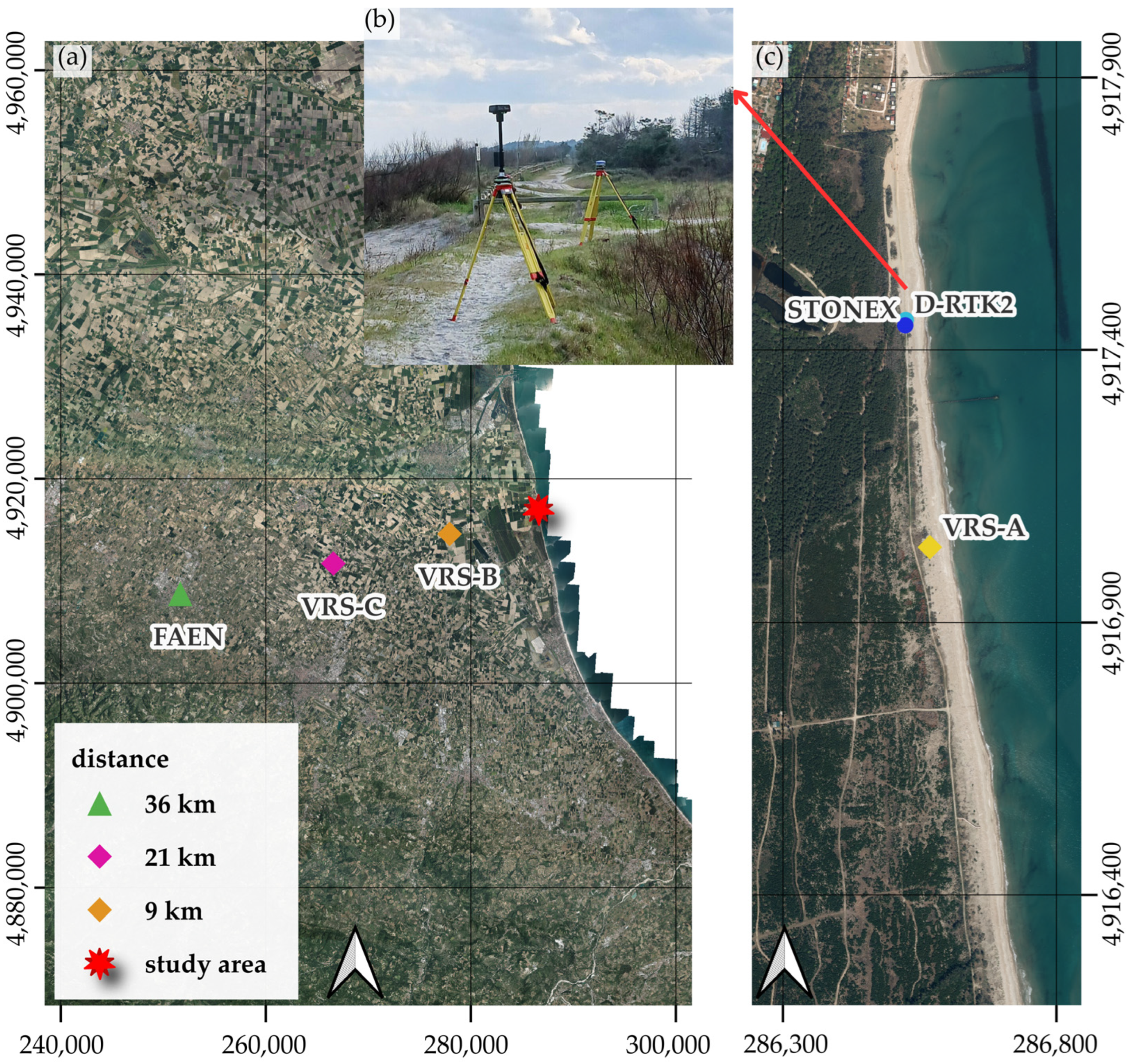

2.3. GNSS Observation Data: Native and Third-Party Base Stations

In this work the UAV-LiDAR processing was performed using different base stations located at various distances from the study site (

Table 1,

Figure 3):

- (i)

D-RTK2 and STONEX are two temporary base stations installed on the site using a tripod, with the first serving as the system’s native base station.

- (ii)

VRS-A, VRS-B, and VRS-C are three virtual reference stations [

47] located respectively on the site, 9 km away, and 21 km away, computed by HxGN SmartNet [

48].

- (iii)

FAEN is a permanent base station of the HxGN SmartNet [

48], located 36 km away.

2.4. UAV Survey

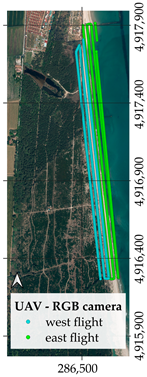

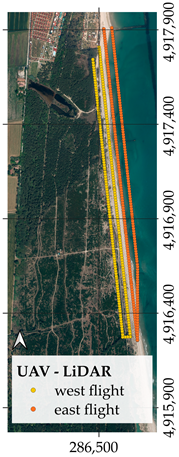

The DJI “Matrice 300 RTK” UAV, carrying first the DJI “Zenmuse P1” payload (RGB camera) and then the DJI “Zenmuse L1” payload (LiDAR sensor), was used to cover the entire area of interest.

Before executing the planned flights, the UAV and its own base station “D-RTK2” were both linked to the ground station (GS). The base station was assigned the coordinates collected in the field using the STONEX “S900A” GNSS receiver in NRTK-VRS mode. This setup enables real-time correction of the UAV’s position during the flight and simultaneously stores data that are already georeferenced in the national datum RDN2008.

Due to the limited battery endurance of the UAV, acquisition of the entire area was divided into four flights, two for each sensor. To exploit the low tide of the day and maintain coherence in the dynamic foreshore area, each sensor survey was split into two parallel flights covering the eastern and western portions of the area, respectively.

2.4.1. RGB Camera and Photogrammetric Processing

The DJI “Matrice 300 RTK” UAV, carrying the DJI “Zenmuse P1” payload (RGB camera), was used to collect about 1262 pictures (

Table 2) at a fixed flight height of approximately 45 m, due to flight constraints on the area. A forward and side overlap of 80% and 60%, respectively. The survey, carried out through two planned flights using the DJI Pilot [

49] platform, started at 13:02 (GMT) and ended at 13:47 (GMT) on 11 March 2025.

The images collected by the P1 payload are processed using the photogrammetric software Agisoft Metashape [

50], following these steps:

The capture locations, collected in the geographic system RDN2008 with ellipsoidal height, are converted by the software convER2021 into the projected cartographic system RDN2008/UTM33, retaining the ellipsoidal height. The images and their new metadata are imported into Metashape to be processed together.

Tie point detection is performed at the original image resolution, with a reduced processing time thanks to the use of a coarse-to-fine strategy (generic preselection) and the use of known capture locations (source reference preselection).

A first computation of the external and internal orientation parameters is carried out using both the tie point positions (image CRS—coordinate reference system) and the capture locations (absolute CRS).

The bundle-adjustment is refined using the known GCP locations (both in the image and absolute CRS) and the camera calibration parameters (f, cx, cy, k1, k2, p1, p2) are optimized.

Poor-quality tie points (with a reprojection error greater than 0.5 pixels) are progressively removed, and the camera calibration parameters (f, cx, cy, k1, k2, p1, p2, b1, b2) are further optimized.

The residual errors of both GCPs (Q03, D12, D11, D10, D09, D07, D06, D05) and Check Points (D15, D14, D13, D04, D03, D01, CS09, CS07, CR1) are evaluated. The GCPs exhibit an RMSE of about 2.8 cm and a maximum error of about 4.4 cm (D07); the check points show an RMSE of about 3.5 cm and a maximum error of 5.9 cm (D14).

Dense image matching is performed at high resolution (1/4 of the original image resolution) with mild filtering.

The dense point cloud is filtered by removing low-quality points. Points with a confidence score ≥ 3 are retained in the dune area, while those ≥5 are retained in the shore zone.

A DSM is generated by interpolating the filtered dense point cloud (ground sampling distance—GSD = 1.66 cm).

An orthomosaic is generated using an average blending mode and the DSM as the reference surface (GSD = 0.83 cm).

2.4.2. LiDAR Sensor and Data Processing

The DJI “Matrice 300 RTK” UAV, carrying the DJI “Zenmuse L1” payload (LiDAR sensor), was used to collect the range data (

Table 3) at a fixed flight height of about 45 m, due to flight constraints over the area. Moreover, the survey was conducted with a side overlap of 20% and a simultaneous collection of pictures, ensuring both strip relative adjustment and point cloud coloring. The survey was carried out by two planned flights using the DJI Pilot software, which started at 14:04 (GMT) and ended at 14:51 (GMT) on 11 March 2025.

UAV-LiDAR systems are composed of cooperative components: each device has its own uncertainties, along with errors related to their cooperation. In summary, the total error budget associated with a UAV-LiDAR system consists of the following [

19,

20,

39]:

Trajectory positioning errors (e.g., number of satellites, satellite geometry, signal blockage, distance of the GNSS base station, incorrect measurement of the base location or antenna offset).

Trajectory orientation errors (e.g., IMU performance).

Scanning mechanism errors (e.g., system design, measurement method, scanning angle, beam divergence).

Lever-arm errors (i.e., the errors related to the vector between the GNSS antenna and the IMU, usually measured by the manufacturer).

Bore-sight errors (i.e., the errors related to the parameters that compute the relative orientation between the IMU and the scanning mechanism, usually determined by a calibration procedure).

GNSS/IMU cooperation is essential because the high rate of inertial measurements can smooth some short-term GNSS-related errors, such as weak satellite geometry or temporary loss of GNSS signal. At the same time GNSS observations can minimize possible systematic IMU-related errors. In contrast to ALS (airborne laser scanning), unmanned vehicles usually fly at a shorter distance (about 50–120 m) and have a shorter lever arm, [

32] allowing for the adaption of lower accuracy IMU and laser scanner, while the GNSS unit remains of considerable importance.

Table 4 lists the accuracy provided by the manufacturer for each unit and for the entire system used in this work. This type of system is easy to use because sensor calibration is performed by the manufacturer and the proprietary software is designed to read, manage, and optimize the sensor data to generate the final LiDAR point cloud and related derived products. This means that the user has limited data accessibility, as the collected information is typically processed internally without user intervention. However, one aspect where the user retains some control is the selection of the GNSS base station [

51] used for trajectory relative positioning correction.

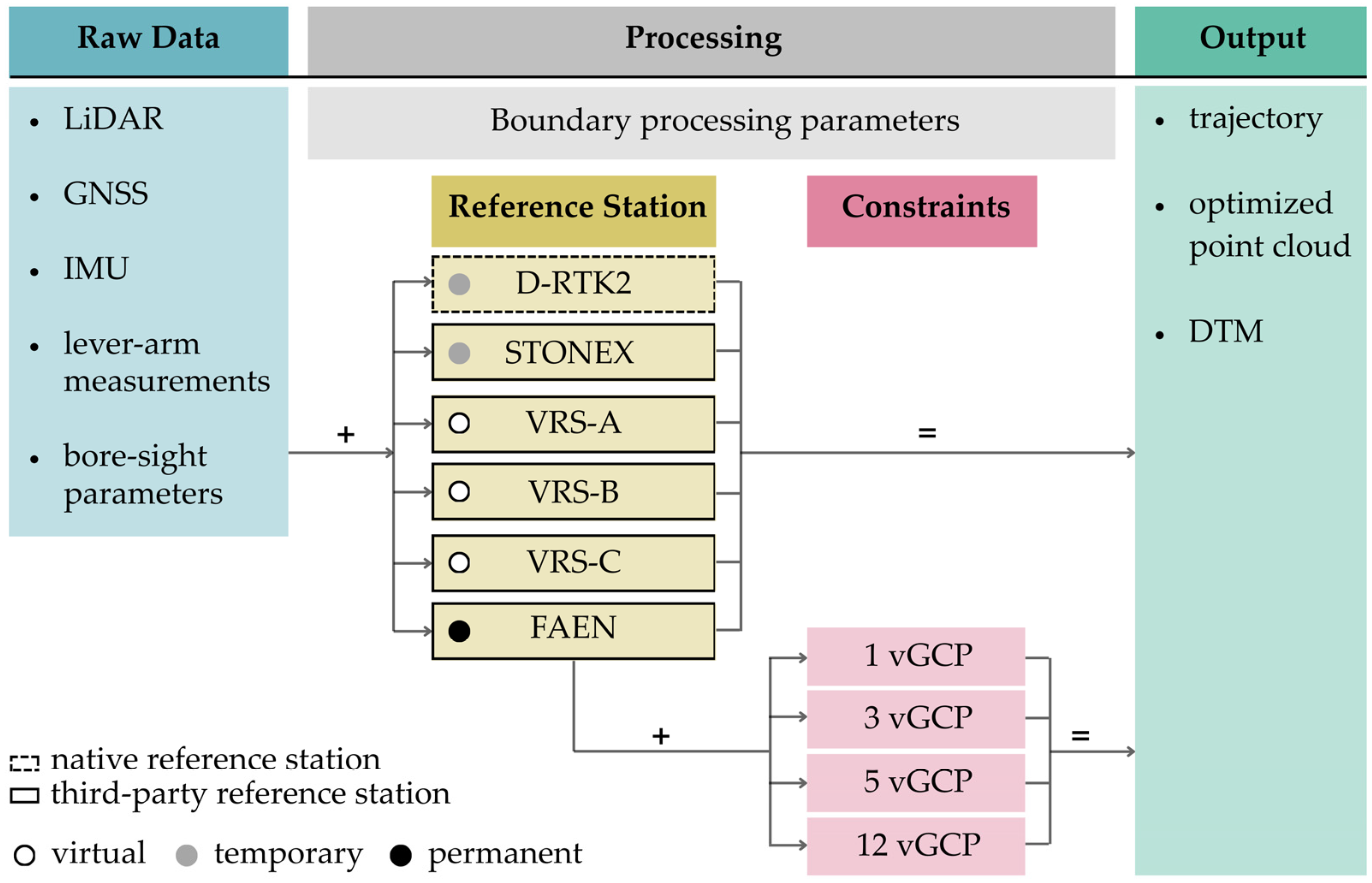

The LiDAR processing workflow is schematized in

Figure 4. On the left are the raw data stored on the UAV microSD card after the survey (LiDAR range data, GNSS observations, IMU data, lever-arm measurements, bore-sight parameters). On the right are the final outputs (trajectory, optimized point cloud, digital terrain model). In the middle there are the possible processing implementations, including boundary processing parameters combined with the choice of the GNSS base station and the integration of elevation constraints. The different LiDAR processing tests are performed via the proprietary software DJI Terra [

52], using the same processing settings (

Table 5).

While maintaining the same boundary processing parameters, it is possible to influence the results by varying the GNSS base station and/or applying elevation constraints. Since GNSS observation files recorded in real-time may contain missing data, it is reasonable to process the original observation files stored at the base station. In this work, six different base stations are adopted (

Figure 4): (1) the native D-RTK2 station (2) the temporary STONEX base station; (3) the VRS-A located in proximity of the site; (4) the VRS-B located about 9 km away; (5) the VRS-C located about 21 km away; (6) the FAEN permanent station, located 36 km away. In addition, four tests are performed on the FAEN base station, introducing 1, 3, 5, and 12 vGCPs, respectively.

It is important to note that DJI Terra software does not currently support the use of an antenna calibration file [

52] capable of integrating the PCV (phase center variation) into the relative trajectory processing. Let “Δ

P,ARP” denote the vertical distance between the station point on the tripod and the ARP (antenna reference point), and “Δ

ARP,R” the vertical distance between the ARP and the mean phase center. The position of the base stations is then computed as follows:

- -

D-RTK2: (lat, lon, h) coordinates computed in NRTK-VRS mode + ΔP,ARP + ΔARP,R.

- -

STONEX: (lat, lon, h) coordinates computed in NRTK-VRS mode + ΔARP,R.

- -

VRS-A, VRS-B, VRS-C, and FAEN: (lat, lon, h) coordinates provided by HxGN SmartNet + ΔARP,R.

Despite these limitations, the user’s interaction with DJI Terra software allows for two types of considerations:

2.5. Comparison Method

All the final data (target coordinates, photogrammetric DSM, UAV-LiDAR trajectories, and LiDAR DTMs) need to be compared to evaluate the performance and trends of each test. In particular, three different levels of comparison are performed (

Figure 5): (i) the elevation difference between check points (CPs) and LiDAR DTM values; (ii) the elevation difference between the LiDAR DTM and the photogrammetric DSM values; (iii) the East, North, and height differences between the trajectories. For each comparison, one set of data is defined as the reference value and the other as the compared data. In this context, the error is defined as the difference between the compared and the reference value.

The statistics computed for each test are:

- (i)

Mean: the arithmetic mean of the difference values.

- (ii)

MAE (mean absolute error): the average of the absolute errors.

- (iii)

RMSE (root mean square error): the square root of the average squared errors.

- (iv)

SD (standard deviation): standard deviation computed on the entire population of errors.

All these statistics are relevant for understanding the behavior of each test: the mean shows how the errors are compensated, while the SD indicates how they are distributed around the mean. Moreover, while the RMSE describes the coherence of the compared model with the predictive one, a similarity between the mean and MAE may indicate a possible systematic bias in the compared model.

Moreover, for each of these analyses, a python script compatible with QGIS has been created (see

Supplementary Materials):

- -

PT2DEM: This algorithm enables a Point-to-DEM comparison.

It compares multiple DEMs against a reference vector point layer. This analysis evaluates the elevation values at the point locations (E, N). Finally, it generates a statistical report (mean, MAE, RMSE, SD, max, min) and a shapefile containing the computed values attached to the point layer, enabling an assessment on the spatial distribution of the differences.

- -

DEM2DEM: This algorithm enables a DEM-to-DEM comparison.

It compares multiple DEMs against a reference DEM. Finally, it generates a statistical report (mean, MAE, RMSE, SD, max, min), a graphical report (difference-frequency), and a difference raster for each compared DEM. Optionally, a polygon mask and a cut-off value can be used to filter the difference values.

- -

T2T: This algorithm enables a Trajectory-to-Trajectory comparison.

It processes the DJI Terra SBET trajectories to compute the trajectory differences (East, North, height, planimetric, absolute) relative to a reference trajectory. Finally, it generates a statistical report (mean, MAE, RMSE, SD, max, min), a graphical report (time-difference), and a shapefile containing the average differences along each compared track, enabling an evaluation of the spatial distribution of the differences.

3. Results

3.1. Point-to-DEM

The Point-to-DEM comparison can serve as an initial assessment to evaluate the overall impact of the GNSS base station choice on the final output, although it relates only to the vertical component. Moreover, summing the assumed uncertainties linked to both the targets and LiDAR DTM (of about 3.5 and 5.0 cm, respectively), the error associated with the point-to-DEM difference results in σPT2DEM = ±6 cm, which sets the threshold for negligible differences in the evaluation.

The estimation of elevation differences between the check points (CPs) and the compared LiDAR DTMs at the (E, N) point locations reveals three distinct trends (

Table 6):

- (i)

The GNSS base stations located in the area and mounted on a tripod show the best performance, with lower RMSE and SD values (approximately 3.6/2.4 cm and 2.3/2.4 cm, respectively). Moreover, the bias, if present, is minor (−2.7 cm for the native base station).

- (ii)

The three VRSs show similar trends, and do not appear, at least in this first comparison, to be influenced by their distance from the site. Compared with the physical base stations located in the area, they exhibit higher RMSE values (ranging from 5.5 to 6.3 cm) and bias (ranging from −4.3 to −5.4 cm), along with larger errors (ranging from −9.7 to −12.0 cm).

- (iii)

The FAEN permanent base station, which is the most distant one, shows the worst statistics, with a bias of −11.0 cm, an RMSE of 11.9 cm, and maximal errors reaching approximately −19.8 cm.

As expected, while the distant base station shows the worst statistics, the temporary base stations situated in the area exhibit the most consistent outcomes, although they may introduce bias due to uncertainties in the base station position estimation. Though the three VRS stations show good statistics, their behavior requires further evaluation. For example, assessing trajectory variations with respect to the GNSS base station selection is essential to understand the distribution of errors.

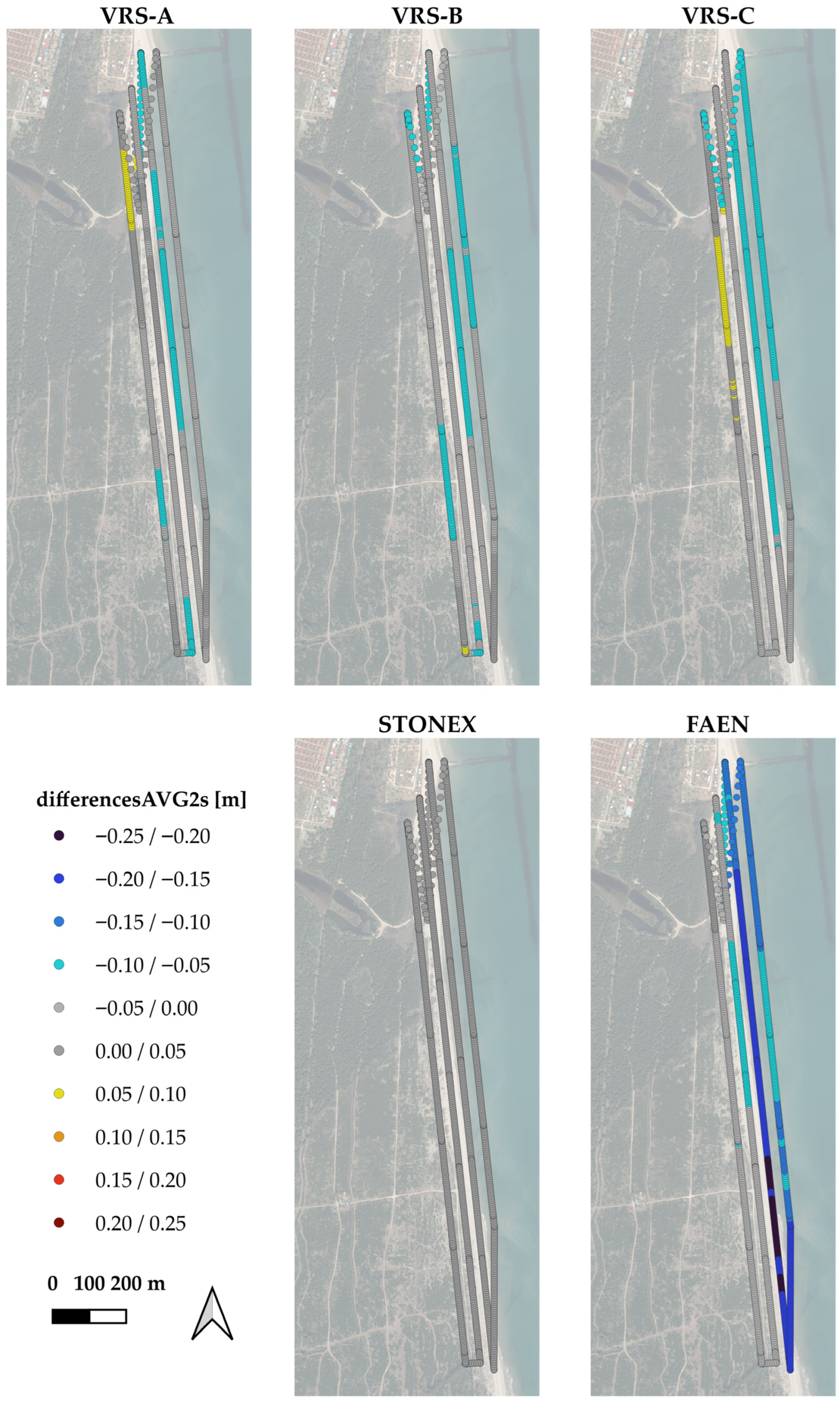

3.2. Trajectory-to-Trajectory

The trajectory difference can identify errors not only in the vertical component (h), but also in the horizontal components (E, N). In this context, the reference model is defined as the one obtained using the native base station (D-RTK2), while all third-party base stations (STONEX, VRS-A, VRS-B, VRS-C, FAEN) are treated as compared models. Moreover, summing the uncertainties linked to the GNSS data (of about 3.5 cm) the error associated with the trajectory difference results in σT2T = ±5.0 cm, establishing the threshold for negligible differences in the test evaluation.

While the differences along the planimetric components (E, N) do not show significant variations in relation to the GNSS base station used (

Table 7 and

Table 8) with RMSE values ranging approximately between 1.0 and 2.2 cm, the elevation component (h) is the most affected by changes in the GNSS base station (

Table 9). Moreover, the T2T function can average the high-rate difference values over a defined interval, enabling the visualization of the spatial distribution of errors. In this work, the averaging interval is set to 2 s, and the color ramp reflects the error associated with the trajectory difference (σ

T2T = ±5.0 cm), where negligible differences are shown in grey.

The statistical and spatial distribution of the errors along the h component reveals three distinct trends (

Table 9,

Figure 6):

- (i)

The temporary base station placed in the area on a tripod is the most consistent relative to the native base station, with an RMSE of about 2.3 cm and a low bias of 2.2 cm. In fact, the grey color is spread along the entire track highlighting strong agreement between the two models.

- (ii)

The three VRSs show good performance, with RMSE between 3.4 and 5.1 cm and a bias ranging between −1.7 cm and −3.3 cm, both increasing with the distance from the site. However, they also exhibit sporadic larger errors ranging from 5.2 to 8.4 cm and from −7.4 to −9.8 cm, spatially visible in yellow and light blue, respectively.

- (iii)

The FAEN permanent base station, the most distant one, exhibits the worst performance, with an RMSE of 11.1 cm, a wider distribution of the differences (SD of 6.7 cm), the highest bias (~−8.9 cm), and the largest differences (~−20.6 cm). Spatially, it shows a wider range of random errors, spanning from −5.0 cm to −20.0 cm (from light blue to black).

As expected, the temporary base station situated in the area shows the most consistent outcome, while the more distant base station exhibits the worst statistics and differences. Moreover, the three VRSs, despite showing good statistics, exhibit random deviations above the negligible threshold, highlighting worse performance compared to physical base stations.

It is therefore important to assess how these differences in trajectory estimation affect the final output, with a DEM-to-DEM comparison, especially since the most significant trajectory differences relate to the height component and are randomly distributed.

3.3. DEM-to-DEM

The difference between the photogrammetric DSM and the compared LiDAR DTMs can show how the trajectory-related errors affect the elevation component of the final output. Moreover, summing the uncertainties linked to both LiDAR DTM and photogrammetric DSM (of about 5.0 cm) the error associated with the DEM difference results in σDEM2DEM = ±7.0 cm, establishing the threshold for negligible differences in the test evaluation.

It is important to underline that for a better statistical evaluation of the errors, a cut-off needs to be applied, to minimize the effect of outliers related to vegetation in the DSM. In this work a cut-off of 4σ

DEM2DEM (±28.0 cm) is applied for the statistics (

Table 10), and the dark blue color (

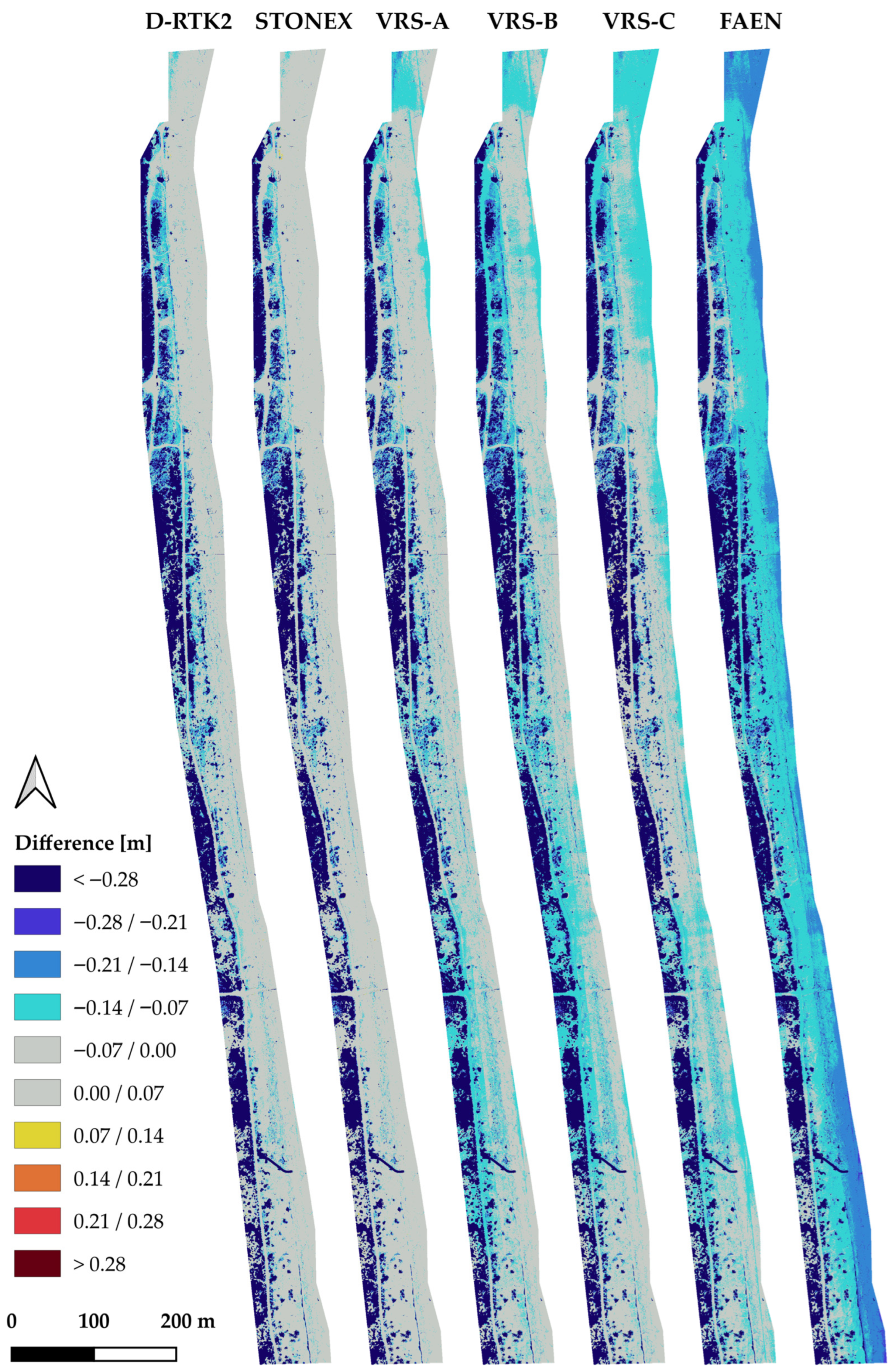

Figure 7) highlights the outlier areas characterized by vegetation and anthropic features.

In this work, as with the Point-to-DEM and Trajectory-to-Trajectory comparisons, the statistical and spatial distribution of the errors reveal three trends (

Table 10,

Figure 7):

- (i)

The GNSS base stations located in the area, mounted on a tripod, show the best performance, with RMSE between 6.0 and 7.1 cm, and a bias between −3.3 and −5.4 cm. In fact, the spatial distribution of errors shows a great coherence between these compared models and the photogrammetric one, with a widespread grey color on the beach and road areas.

- (ii)

The three VRSs have an RMSE ranging between 7.9 and 8.8 cm, and a bias between −6.6 and −7.6 cm. Statistically, they show a similar trend, and it does not appear to be related to the distance from the site. However, the spatial distribution of the differences exhibits an increasing non-negligible error (light blue) associated with increasing distance, showing no clear spatial correlation.

- (iii)

The FAEN permanent base station, which is the most distant one, shows the worst statistics, with an RMSE of about 12.6 cm and a bias of about −11.6 cm. In fact, the spatial distribution of the differences shows the largest deviations, ranging from −7.0 to 14.0 cm (light blue) and from −14.0 to 21.0 cm (medium blue), randomly distributed.

Coastal surveys require an accuracy level appropriate to the phenomena being analyzed. Sub-10cm accuracy may be required to support hydrodynamic analyses, coastal erosion modeling, and change detection. Moreover, it is important to consider both the accuracy of the relative reconstruction of model portions and the absolute georeferencing. As seen in all the comparisons, the temporary base stations located in the area may introduce bias linked to the estimation of the base position, but they remain the preferred options, exhibiting the most consistent statistics and a coherent spatial distribution of the differences. The use of VRS is logistically advantageous as it removes the need to deploy a physical base station in the area, but in this case it leads to outcomes with unacceptable accuracy and non-negligible errors, randomly distributed. This indicates that VRS may not meet the requirements of coastal monitoring, as they exhibit a random accuracy loss in the relative reconstruction of the model. The use of permanent stations with well-known positions can be an asset for monitoring purposes, but when the nearest station is farther than the suggested limit [

53] (>15 km), it leads to statistical and spatial issues. These stations may exhibit a loss in both relative reconstruction and absolute georeferencing, both essential for coastal monitoring. However, it is important to note that the accuracy loss related to the use of VRS or distant stations is mainly linked to the height component. Although it is not constant, it may be mitigated using elevation constraints.

3.4. Integration of Vertical Ground Control Points

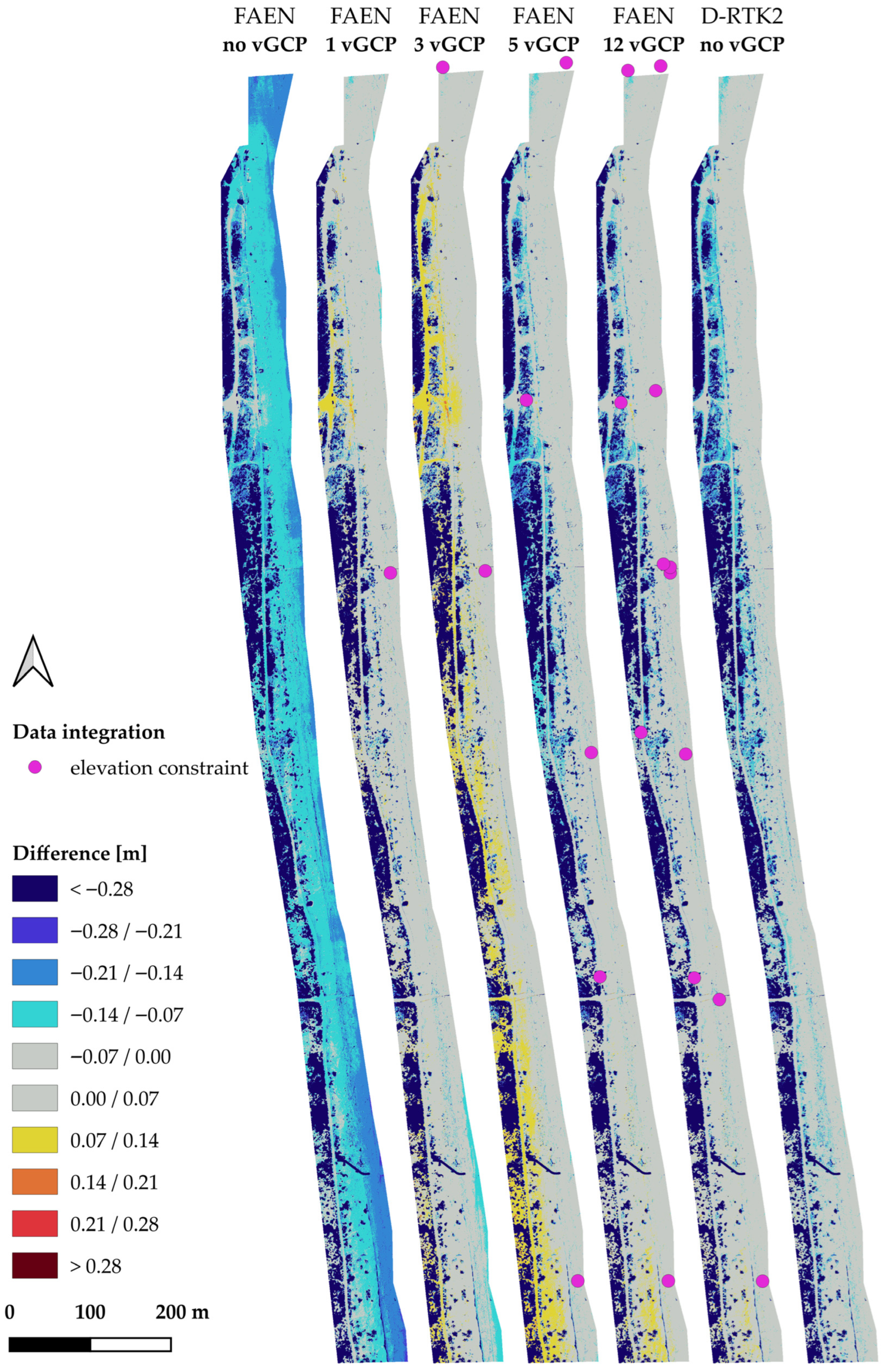

The LiDAR processing performed in this work allows for the integration of vertical ground control points (vGCPs). For this reason, four additional tests are performed to evaluate whether and how the vertical errors can be minimized. These tests use the FAEN base station (i.e., the station that has produced the poorest outcomes) and attempt to minimize the errors using 1, 3, 5, and 12 vGCPs, respectively. Specifically, the points must belong to the ground level, and they are selected as follows: 1 point in the center, 3 points spatially distributed along the study area, 5 points distributed along the area and alternating between the west and east sides, and all 12 points collected homogeneously on the area.

Statistically, all tests show substantial improvement (

Table 11), with an RMSE ranging between 5.6 and 6.9 cm (close to the 7.1 cm of the native model), and a bias ranging between −0.6 and 2.5 cm (compared with −5.4 cm for the native model). However, the spatial distribution of the differences reveals a different behavior (

Figure 8):

- (i)

The use of a single vGCP drastically reduces the vertical bias related to the distance of the GNSS base station used for the PPK, although some areas still show residual errors.

- (ii)

The use of three aligned vGCPs shows strong coherence on the side where the points are placed; however, it causes a deviation on the opposite side (area without constraints).

- (iii)

The use of five vGCPs, alternately placed across the object, yields a strong improvement in the agreement over the beach and road areas, although some small zones still exhibit dissimilarities.

- (iv)

The use of all the available vGCPs (12), alternately placed across the object, minimizes the vertical errors most effectively.

Although the computed trajectory remains the same, the use of only a single elevation constraint significantly enhances the elevation component of the final output. Nevertheless, the use of multiple, spatially distributed constraints may provide a better representation of the scene, minimizing not only the presence of bias but also the influence of random errors on the scene. In fact, a wider spatial distribution of points provides stronger constraints across different portions of the study area. Moreover, statistically, the use of constraints brings the final model closer to the photogrammetric output, since both are processed using the same network of GCPs, whereas the native output remains uncorrelated with the photogrammetric output and may be affected by bias related to the computation of the antenna offset and base station coordinates.

4. Discussion

Coastal environments are vulnerable areas that require protection and monitoring. They represent complex scenarios, as they are dynamic environments also threatened by sea storms and flood risk. Therefore, it is important to plan a monitoring program that is rapid, adaptable to potential changes, and still provides adequate accuracy in relation to the phenomena being analyzed.

In this context, UAV-LiDAR systems have proven to be a significant asset in providing high-resolution 3D representation of coastal environments. These systems require the use of a direct georeferencing procedure, in which the UAV trajectory can be estimated using relative positioning techniques (RTK, NRTK, PPK). However, the choice of the GNSS base station used for trajectory correction can significantly affect the accuracy of the final output. Given these factors, different tests were performed using the same UAV-LiDAR data acquired by the DJI “Matrice 300 RTK” equipped with the L1 payload over a coastal area near Ravenna (Emilia-Romagna, Italy). Six base station configurations were tested:

- (i)

Two base stations temporarily deployed on site using a tripod (one of them is the UAV’s native station)

- (ii)

Three VRSs located respectively on the site, 9 km away, and 21 km away.

- (iii)

One permanent base station located 36 km away.

To evaluate their performance among these alternatives (temporary, permanent, virtual), as well as their dependence on distance from the site, three different levels of comparison were performed: (i) an elevation difference between the check points (CPs) and LiDAR DTM values; (ii) an elevation difference between the LiDAR DTM and the photogrammetric DSM values; (iii) East, North, height differences between the trajectories.

In the following sections, the main findings will be discussed, beginning with the influence of each type of station (temporary, virtual, and permanent), followed by study limitations and a comparison with related works.

4.1. Temporary Stations—Native vs. Third-Party

There are some complex scenarios (e.g., high vegetation, rapid elevation changes, large extent) in which the use of the native base station is not favorable, due to difficulty in maintaining a stable connection throughout the entire flight duration (for both UAV-GS and GS-base links). Consequently, it is important to assess the use of an alternative third-party base station for trajectory post-processing.

Overall, the results of this study show greater coherence when using temporary base stations compared with the other two alternatives (on-site VRS or a distant permanent station), due to reduced baseline errors. When comparing the trajectories, the STONEX station (temporary third-party base station) is the most consistent with the native trajectory. This similarity in the estimated trajectory also leads to a comparable result in the comparison between the LiDAR DTMs and the photogrammetric DSM: these results exhibit an RMSE of about 6.0/7.1 cm and a mean value of about −3.3/−5.4 cm. These biases between the photogrammetric and LiDAR datasets are compatible with the uncertainties associated with the estimation of the base coordinates. However, the use of temporarily deployed base stations on site remains the best option for this study site, despite the uncertainties linked to a temporary configuration.

4.2. Virtual Reference Stations—Strengths and Limitations

The use of virtual reference stations for environmental surveys can be a key element. In fact, it does not require any physical deployment in the study area, making this procedure highly convenient for rapid surveys, even in complex and inaccessible scenarios. Despite the practical ease of using VRS, the results have shown a loss of accuracy compared with temporarily deployed base stations.

When comparing the trajectories, the East and North components can be neglected, while the height component is the most affected. This comparison shows random deviations with respect to the native trajectory, mainly expressed by a wider range of min-max values, between −7.4 cm and 7.2 cm for VRS-A located within the study site. This type of error affects the final model reconstruction. In fact, when compared with the photogrammetric model, a bias of −6.6 cm is observed, partially caused by uncertainty in the base coordinates. In addition, spatially, a random distribution of errors can be seen, with deviations exceeding the 7 cm threshold. In this case, the impact of the trajectory misestimation compromises not only the absolute georeferencing of the model but also the relative height reconstruction, making it unsuitable for coastal monitoring, where overall consistency is required.

4.3. Permanent Base Station—The Impact of the Distance

The use of permanent base stations located near the study area is ideally the best option for monitoring purposes. This configuration enables processing with the same station coordinates for each epoch, thus avoiding the uncertainty associated with estimating them independently at each epoch. However, this option is often not feasible, as permanent base stations may be located far from the survey site.

In this study area, the permanent base station (FAEN) is about 36 km away, which is greater than the maximum baseline recommended in the literature and by the software [

54] (15 km). Using such a base station is not ideal, but in some cases it may be the only option available, as it is the closest to the site.

The results show that using a base station at such a distance can affect the trajectory estimation and, ultimately, the output elevation model. When comparing the output trajectory to the native one, the East and North components can be neglected, while the height component is the most affected. In the height component, two effects can be observed. First, the mean value shows a bias of about −8.9 cm. Second, the error distribution is random, which is reflected in a higher standard deviation and a broader range of min-max values (from −20.6 cm to 4.7 cm). When comparing the LiDAR DTM with the photogrammetric DSM, the results show a bias of −11.6 cm and a retained random error distribution, with deviations ranging from about −7.0 to −21.0 cm. This behavior highlights a loss of accuracy not only in the absolute georeferencing but also in the relative reconstruction of the model.

4.4. Vertical Error Mitigation Through vGCPs

The integration of vertical ground control points (vGCPs) into LiDAR processing is in most cases not a feasible solution, considering the usually low resolution of the LiDAR point cloud and the difficulty of accurately collimating targets. Likely due to this limitation, DJI Terra software only allows the integration of vertical constraints, which are coordinates with known elevation values.

The integration of vertical constraints can be a valuable tool for minimizing the elevation errors present in LiDAR processing. As described above, this type of elevation error has two main trends: a vertical bias and a random error distribution. While the use of a single constraint may be able to remove the vertical bias, an occasional presence of errors may still be observed.

The test evaluating constraint integration was performed using the worst-case scenario (FAEN—distant permanent station), integrating 1, 3, 5, and 12 vGCPs, respectively. Statistically, all tests show an improvement, reducing the bias from −11.6 cm to approximately −0.6/2.5 cm. However, the visual distribution of the errors shows that not all tests have an overall consistency along the study site. In fact, the spatial arrangement of the constraints may not be sufficient to reduce the stochastic nature of the deviations. For example, when using a single vGCP, small portions with higher errors (up to 7 cm) remain, and using 3 vGCPs aligned along the eastern part leads to a loss of consistency in the western area (up to 7 cm).

In addition, these tests appear to perform statistically better than using the native temporary base station without vGCPs. It is clear that using vGCPs in LiDAR processing makes it more consistent with the photogrammetric DSM, which is also georeferenced using the same GCPs. LiDAR has no inherent redundancy, and the final error budget can easily be affected by additional bias and uncertainties. For example, temporarily deployed base stations can introduce residual biases in the output, such as uncertainties linked to the base coordinates and the antenna phase center. This makes the deployment of targets advantageous, as they can serve both as constraints to mitigate residual biases and as final quality control for LiDAR-derived outputs. The coastal environment may not be ideal for this purpose, as it is highly dynamic. However, other environmental settings may be more suitable for building a permanent network of stable points that can be used to minimize residual vertical deviations and correctly georeference multi-temporal data.

4.5. Study Limitations

Firstly, the results refer to a specific study area, specifically a coastal environment located at the edge of the CORS (continuously operating reference station) network. For this reason, it would be valuable to evaluate the use of VRS under different CORS network geometries and to assess the use of closer permanent stations, since the nearest station in this study exceeded the theoretical 15 km baseline limit.

Secondly, using consumer-grade system with related proprietary closed-source software does not allow open accessibility for integrating data collected by each unit (GNSS, IMU, bore-sight). The manufacturer is responsible for system calibration, and the user may be unable to assess sensor miscalibration. For these tests, it is assumed that the error associated with the choice of the GNSS base station is more significant than the error arising from system calibration.

Finally, it appears that the software used does not include ANTEX files. This means that it does not automatically recognize the antenna type. The user must manually enter not only the antenna height but also the mean antenna offset. Consequently, trajectory processing does not account for phase center variation, which can lead to errors arising from antenna geometry and satellite configuration during the survey. However, it is notable that this issue is not explicitly highlighted in similar studies or documentation. This highlights a broader issue regarding the transparency of the LiDAR processing workflow: while the system and processing are easy to use, users may introduce errors due to limited understanding of how the processing procedure is implemented.

4.6. Comparison with Related Works

Both Bartmiński et al. [

31] and Kersten et al. [

34] use the same UAV-LiDAR system as this study, though showing different performance. They do not clearly state which base station was used for data processing, making a direct comparison with this work difficult. Instead, it is useful to compare the current results with the analysis conducted by Dreier et al. [

36]. Although the scenario, equipment, and comparison procedure differ, Dreier et al. investigated, as in this work, the use of different base stations for UAV-LiDAR direct georeferencing. Their first test involved processing a single UAV-LiDAR strip at a flight height of 10 m, using a base station on a pillar (baseline = 1 km), two VRSs (baselines of 1 and 2 km), and a CORS station (baseline = 16 km). Comparing the target coordinates with a TLS (terrestrial laser scanning) reference, they obtained statistically similar results for all stations, supporting the use of all alternatives. By contrast, their second test, based on processing a multi-strip acquired at a flight height of 25 m, processed using a VRS, yielded results more comparable to those of this study: a mean absolute error of about 4.3 cm (vs. 4.7 cm for VRS-A) and a maximum error of about 8 cm (vs. 10 cm for VRS-A). This supports the idea that the use of virtual reference stations may warrant further investigation, particularly regarding the geometry of the CORS network. In this context, it could be valuable to investigate not only the final output but also the computed trajectories, as in the present work. Moreover, another notable similarity between these two studies is the presence of bias in all tests, mainly related to the height component. As suggested in Dreier et al., the present work supports the validity of using vertical constraints to minimize this bias, although the distribution of constraints may sometimes be insufficient to maintain overall consistency.

In this context, correctly registering point clouds is essential for reliable change detection analysis and to avoid misestimating volume changes [

30]. One possible approach is the rigid co-registration of point clouds based on reference areas [

17], or a non-rigid co-registration performed through the joint processing of multiple dataset, as proposed by Pöppl et al. [

33]. However, these procedures may not be effective in dynamic environments lacking stable areas between survey epochs. Instead, Štroner et al. [

35] tried to minimize the georeferencing error in the point cloud through transformations computed from a network of highly reflective targets. In their case, the point cloud was not affected by rotational errors but only by biases along the axes, which could be removed via translation. This procedure is similar to that adopted in this study, although the vertical ground control points (vGCPs) only correct the height component, which is the most affected when using suboptimal base stations. In other words, both Štroner et al. and the present study focus on errors linked to GNSS-related uncertainties and their minimization through additional surveyed constraints. However, this makes the procedure slower and less applicable in inaccessible scenarios. For monitoring purposes it may be more appropriate in the future to investigate the UAV-LiDAR stability across multi-epoch surveys, using a permanent base station to reduce georeferencing biases.

Finally, it is not possible to make a direct comparison with the work of Cao et al. [

37], because the type of base station used is not indicated. However, their work is based on integrating UAV-LiDAR and USV-SBES data to create a continuous topo-bathymetric model. This objective highlights the importance of achieving both relative and absolute data consistency and underscores the relevance of the present work, which seeks to reduce GNSS-related errors prior to subsequent processing. In fact, minimizing these uncertainties enables improved performance in key coastal monitoring tasks (e.g., integration with SBES data, change detection analysis, and coastal erosion modeling).

5. Conclusions

UAV-LiDAR system requires the use of a direct georeferencing procedure, in which the UAV trajectory can be estimated using relative positioning techniques (RTK, NRTK, PPK). Using a consumer-grade system and related proprietary software limit user control over data integration (GNSS, IMU, LiDAR). However, the user can influence the final result, varying the GNSS base station for the trajectory correction.

In this work, it has been analyzed how the GNSS base station type (temporary, permanent, or VRS) and its distance from the survey site affects UAV-LiDAR direct georeferencing accuracy, and whether integrating vertical ground control points (vGCPs) can mitigate vertical deviations induced by suboptimal base stations. The comparison is carried out using novel QGIS tools (PT2DEM, DEM2DEM, T2T), comparing both estimated trajectories and the final outputs. In this way, it is possible to evaluate how trajectory miscalculations can lead to accuracy loss by comparing the LiDAR DTM with reference data (target network or photogrammetric DSM).

In this specific coastal environment, the results show a greater coherence when using temporarily deployed base stations, although they can be influenced by uncertainties of the base coordinates. The use of VRS is convenient especially for inaccessible scenarios, while they may contain both uncertainties linked to the base coordinates and a wider range of random errors, compromising the accuracy in the relative height reconstruction. In contrast, a permanent base station will avoid the uncertainty associated with estimating its coordinates independently at each epoch. However, a near permanent station is not always available, and the use of distant solutions, outside the recommended baseline limit (15 km), leads both to a loss in the absolute georeferencing (presence of a vertical bias) and in the relative reconstruction (wider random error distribution). In this context, while the use of a single constraint can remove the vertical bias, an occasional presence of errors may still be observed. In fact, the spatial arrangement of the constraints may not be sufficient to reduce the random noise of the deviations.

To ensure correct hydrodynamic understanding, coastal erosion modelling and change detection evaluation, coastal monitoring may require both accuracy in the relative reconstruction of the model and the absolute georeferencing. Having a clear overview of the alternatives available on a specific site can help plan a more efficient monitoring procedure in relation to the phenomena being observed, while at the same time be aware of the possible alternatives with linked uncertainties. These alternatives may be adopted, for example, for post storm assessment, characterized usually by not fully accessible areas. The open question remains the overall consistency over a multi-epoch survey. In literature, usually the data are relatively roto-translated, using stable areas or matching points. However, dealing with a coastal environment may not be ideal for both the procedure, since it is a highly dynamic environment and finding stable portions is not easy. This issue may drive further investigation into a broader use of permanent stations or VRSs for environmental monitoring purposes, also quantifying the uncertainties linked to the CORS geometry, the antenna type and the processing pipeline.