Multi-Sensor Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance via Perez–Ineichen and Deep Neural Networks

Highlights

- The combination of the Perez–Ineichen (PI) model with a Deep Neural Network (DNN) for accurate urban solar irradiance (USI) prediction in Wuhan using high-resolution Sentinel-2 data.

- Spectral-band selection and attention mechanism techniques are utilized to enhance the accuracy of solar irradiance prediction.

- Comprehensive error analysis is conducted to identify the limitations of irradiance predictions particularly under cloud-affected conditions and to propose directions for future improvements.

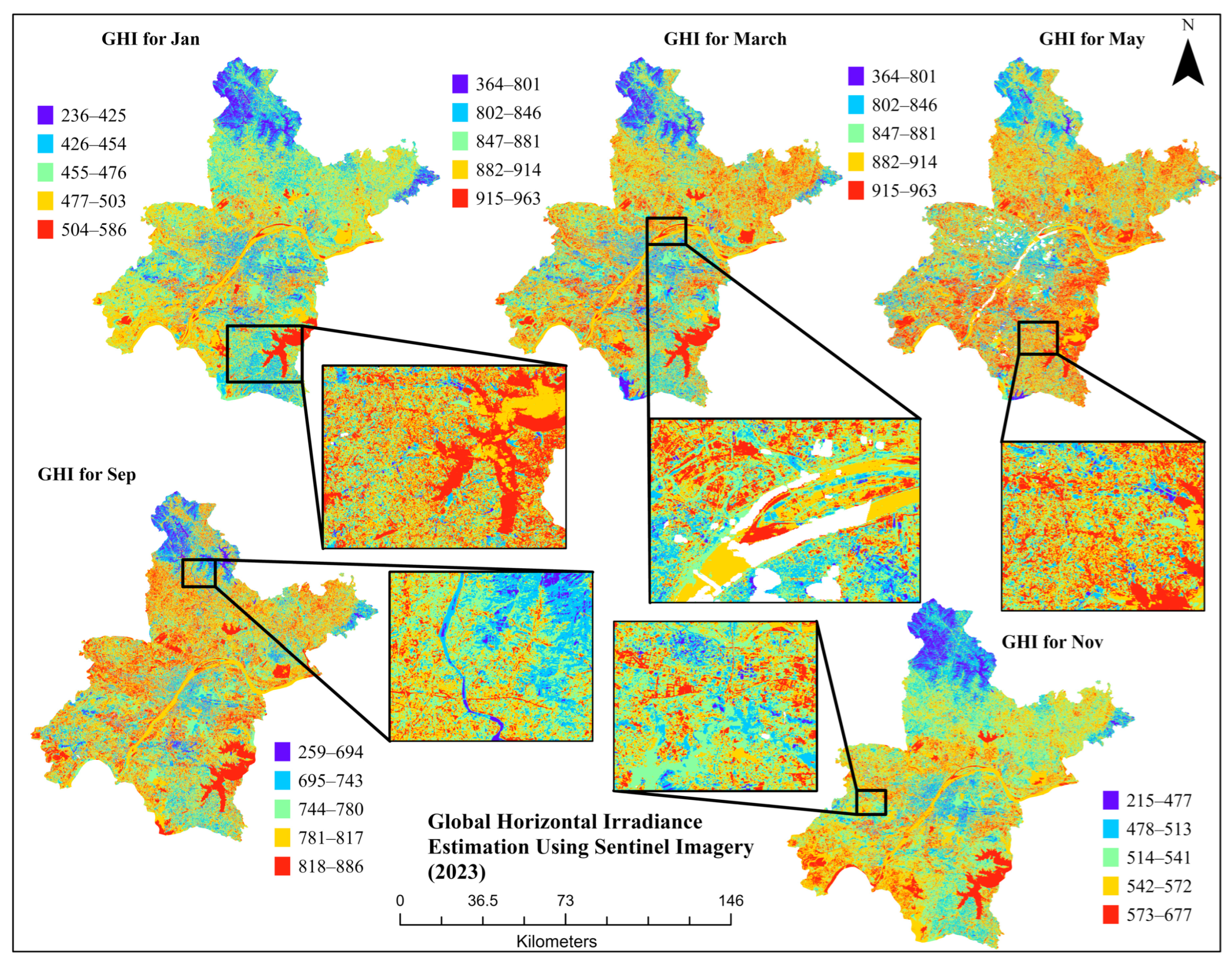

- Validation using hyperspectral imagery: Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) and Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) maps produced by the model are compared with reference hyperspectral GHI maps derived from Sentinel-2 imagery to assess accuracy and reliability.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The combination of PI with DNN for accurate USI predictions in Wuhan, utilizing high-resolution Sentinel-2 data.

- Spectral-band selection and attention mechanism methods are utilized to aid in improved solar irradiance prediction.

- Error analysis is being performed to understand the shortcomings of irradiance predictions, especially under cloud conditions, and offers future improvement methodologies.

- Validation via hyperspectral imagery: Global Horizontal Irradiance (GHI) and Direct Normal Irradiance (DNI) maps produced by model outputs compare with genuine hyperspectral GHI maps from Sentinel-2 imagery for accuracy and reliability of model predictions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Atmospheric and Geospatial Data Acquisition

2.2. Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance

2.3. Preprocessing

2.4. Clear-Sky Index Estimation

2.5. Deep Neural Network-Based Solar Irradiance Estimation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Deep Neural Networks for Solar Irradiance Estimation

3.2. Comparing Performance in Clear-Sky and Cloudy Conditions

3.3. Error Analysis

3.4. Solar Irradiance Estimation Using Sentinel-2 Imagery

3.5. Validation of GHI and DNI Estimates Using Hyperspectral Imagery

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Dataset | Type | Coverage | Temporal Frequency | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-2 | Multispectral | Large (100+ km2) | Every 5 days | Main dataset for GHI/DNI modeling |

| EnMAP | Hyperspectral | Small (30 km width) | Single date | High-quality reference (validation) |

| Parameter | Access Date | Dataset |

|---|---|---|

| NDVI, Solar Geometry, Albedo | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | https://www.enmap.org/ |

| Aerosol Index | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | Sentinel-5P NRTI L3 Aerosol Index (COPERNICUS/S5P/NRTI/L3_AER_AI) |

| Solar Azimuth | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | Sentinel-5P NRTI L3 Aerosol Index (COPERNICUS/S5P/NRTI/L3_AER_AI) |

| Solar Zenith Angle | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | Sentinel-5P NRTI L3 Aerosol Index (COPERNICUS/S5P/NRTI/L3_AER_AI) |

| Air Temperature | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | ERA5 Daily Aggregates (ECMWF/ERA5/DAY) |

| Cloud Mask | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | Sentinel-2 Surface Reflectance (COPERNICUS/S2_SR) |

| Clear Sky Index | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | Sentinel-2 Surface Reflectance (COPERNICUS/S2_SR) |

| Atmospheric data | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | https://nsrdb.nrel.gov |

| All spectral bands | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | COPERNICUS/S2_SR_HARMONIZED |

| Altitude (Elevation) | Accessed on 18 June 2024 | SRTM Digital Elevation Model (USGS/SRTMGL1_003) |

| District | Air Temperature (°C) | Altitude (m) | Latitude DD:DD | Longitude DD:DD | Cloud Probability % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hannan | 18.2 | 25 | 30.28 | 114.01 | 47 |

| Caidian | 18.2 | 17 | 30.64 | 113.93 | 10 |

| Dongxihu | 18.3 | 21 | 30.64 | 114.11 | 40 |

| Hanyang | 18.3 | 23 | 30.56 | 114.19 | 21 |

| Hongshan | 28.3 | 15 | 30.64 | 114.55 | 5 |

| Huangpi | 27.6 | 18 | 30.82 | 114.47 | 5 |

| Jianghan | 18.3 | 16 | 30.60 | 114.27 | 4 |

| Jiangxia | 26.5 | 16 | 30.20 | 114.47 | 4 |

| Qiaokou | 18.3 | 17 | 30.58 | 114.21 | 17 |

| Qingshan | 28.4 | 22 | 30.64 | 114.37 | 8 |

| Wuchang | 26.2 | 20 | 30.56 | 114.37 | 8 |

| Xinzhou | 28.3 | 16 | 30.74 | 114.73 | 6 |

| Jiangan | 8.3 | 19 | 30.64 | 114.29 | 26 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| All Bands | Standard Scaler |

| Selected Bands | Standard Scaler |

| GHI and DNI | Min-Max Scaler |

| Test Size | 0.2 |

| Random State | 42.0 |

| Dense Layer 1 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 256 neurons, activation = |

| Dropout 1 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 0.4 |

| Dense Layer 2 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 128 neurons, activation = |

| Dropout 2 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 0.3 |

| Dense Layer 3 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 128 neurons, activation = |

| Dropout 3 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 0.3 |

| Dense Layer 4 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 64 neurons, activation = |

| Dropout 4 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 0.2 |

| Dense Layer 5 (input all bands; input selected bands) | 32 neurons, activation = |

| Output Layer | 1 neuron, activation = linear |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Loss Function | MSE |

| Metrics | MAE |

| Epochs | 100.0 |

| Batch Size | 32.0 |

References

- Kim, J.; Kim, E.; Jung, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Kim, S. Improved Surface Solar Irradiation Estimation Using Satellite Data and Feature Engineering. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, J.M.; Sun, X.; Gueymard, C.A.; Acord, B.; Wang, P.; Engerer, N.A. BRIGHT-SUN: A Globally Applicable 1-Min Irradiance Clear-Sky Detection Model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 121, 109706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, C.; Xie, Y.; Li, M. Global and Direct Solar Irradiance Estimation Using Deep Learning and Selected Spectral Satellite Images. Appl. Energy 2023, 352, 121979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Sun, F.; Wang, H. Correct and Remap Solar Radiation and Photovoltaic Power in China Based on Machine Learning Models. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, J.; Ai, B.; Tomoyama, G.; Sakurai, N.; Fujiwara, Y.; Hoshi, T. The Structure of Health Factors among Community-dwelling Elderly People. City Res. 2003, 81, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mendyl, A.; Mabasa, B.; Bouzghiba, H.; Weidinger, T. Calibration and Validation of Global Horizontal Irradiance Clear Sky Models against McClear Clear Sky Model in Morocco. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.E.; Hasenauer, H.; White, M.A. Simultaneous Estimation of Daily Solar Radiation and Humidity from Observed Temperature and Precipitation: An Application over Complex Terrain in Austria. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2000, 104, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barancsuk, L.; Groma, V.; Günter, D.; Osán, J.; Hartmann, B. Estimation of Solar Irradiance Using a Neural Network Based on the Combination of Sky Camera Images and Meteorological Data. Energies 2024, 17, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapakis, R.; Charalambides, A.G. Enhanced Values of Global Irradiance Due to the Presence of Clouds in Eastern Mediterranean. Renew. Energy 2014, 62, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguarda, A.; Giacosa, G.; Alonso-Suárez, R.; Abal, G. Performance of the Site-Adapted CAMS Database and Locally Adjusted Cloud Index Models for Estimating Global Solar Horizontal Irradiation over the Pampa Húmeda. Sol. Energy 2020, 199, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Oumbe, A.; Blanc, P.; Espinar, B.; Gesell, G.; Gschwind, B.; Klüser, L.; Lefèvre, M.; Saboret, L.; Schroedter-Homscheidt, M.; et al. Fast Radiative Transfer Parameterisation for Assessing the Surface Solar Irradiance: The Heliosat-4 Method. Meteorol. Z. 2017, 26, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre, M.; Oumbe, A.; Blanc, P.; Espinar, B.; Gschwind, B.; Qu, Z.; Wald, L.; Schroedter-Homscheidt, M.; Hoyer-Klick, C.; Arola, A.; et al. McClear: A New Model Estimating Downwelling Solar Radiation at Ground Level in Clear-Sky Conditions. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2013, 6, 2403–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, M. Improved Turbidity Estimation from Local Meteorological Data for Solar Resourcing and Forecasting Applications. Renew. Energy 2022, 189, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Lv, T.; Dong, J.; Yang, J.; Lin, Z.; Li, S. Nowcasting of Surface Solar Irradiance Based on Cloud Optical Thickness from GOES-16. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, R.W.; Dagestad, K.F.; Ineichen, P.; Schroedter-Homscheidt, M.; Cros, S.; Dumortier, D.; Kuhlemann, R.; Olseth, J.A.; Piernavieja, G.; Reise, C.; et al. Rethinking Satellite-Based Solar Irradiance Modelling: The SOLIS Clear-Sky Module. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 91, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Yu, Q. Estimating Half-Hourly Solar Radiation over the Continental United States Using GOES-16 Data with Iterative Random Forest. Renew. Energy 2021, 178, 916–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmit, T.J.; Lindstrom, S.S.; Gerth, J.J.; Gunshor, M.M. Applications of the 16 Spectral Bands on the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI). J. Oper. Meteorol. 2018, 06, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ren, J.; Pu, Y.; Wang, P. Solar Energy Potential Assessment: A Framework to Integrate Geographic, Technological, and Economic Indices for a Potential Analysis. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Weng, J.; Kang, Q.; Li, J. Reconstruction of High-Resolution Solar Spectral Irradiance Based on Residual Channel Attention Networks. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajith, M.; Martínez-Ramón, M. Deep Learning Based Solar Radiation Micro Forecast by Fusion of Infrared Cloud Images and Radiation Data. Appl. Energy 2021, 294, 117014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, G.; Gueymard, C.; Galdino, J.B.; de Castro Vilela, O.; Fraidenraich, N. Solar Irradiance Time Series Derived from High-Quality Measurements, Satellite-Based Models, and Reanalyses at a near-Equatorial Site in Brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 117, 109478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Yu, Q. High-Spatiotemporal-Resolution Estimation of Solar Energy Component in the United States Using a New Satellite-Based Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikofski, M.M.; Hansen, C.W.; Holmgren, W.F.; Kimball, G.M. Use of Measured Aerosol Optical Depth and Precipitable Water to Model Clear Sky Irradiance. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 44th Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC 2017), Washington, DC, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liang, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, M. Estimation of High-Resolution Solar Irradiance Data Using Optimized Semi-Empirical Satellite Method and GOES-16 Imagery. Sol. Energy 2022, 241, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, W.; Gueymard, C.A.; Hong, T.; Kleissl, J.; Huang, J.; Perez, M.J.; Perez, R.; Bright, J.M.; Xia, X.; et al. A Review of Solar Forecasting, Its Dependence on Atmospheric Sciences and Implications for Grid Integration: Towards Carbon Neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalasingham, S.; Deo, R.C.; Raj, N.; Casillas-Perez, D.; Salcedo-Sanz, S. Generating High Spatial and Temporal Surface Albedo with Multispectral-Wavemix and Temporal-Shift Heatmaps. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagli, G.M.; Yang, D.; Gandhi, O.; Srinivasan, D. Can We Justify Producing Univariate Machine-Learning Forecasts with Satellite-Derived Solar Irradiance? Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Li, M.; Coimbra, C.F.M. Sun-Tracking Imaging System for Intra-Hour DNI Forecasts. Renew. Energy 2016, 96, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooriyaarachchi, V.; Wijeratne, L.O.H.; Waczak, J.; Patra, R.; Lary, D.J.; Zhang, Y. Enhancing Hyperlocal Wavelength-Resolved Solar Irradiance Estimation Using Remote Sensing and Machine Learning. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.W.; Shu, H.; Tariq, A.; Naz, I.; Ahmad, M.N.; Quddoos, A.; Javid, K.; Mustafa, F.; Aeman, H. Monitoring Landuse Change in Uchhali and Khabeki Wetland Lakes, Pakistan Using Remote Sensing Data. Gondwana Res. 2024, 129, 252–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; Adelodun, A.A.; Kim, K.H. Solar Energy: Potential and Future Prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 82, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Virguez, E.; Shan, R.; Tian, J.; Gao, S.; Patiño-Echeverri, D. High-Resolution Data Shows China’s Wind and Solar Energy Resources Are Enough to Support a 2050 Decarbonized Electricity System. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 117996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.W.; Shu, H.; Naz, I.; Quddoos, A.; Yaseen, A.; Gulshad, K.; Alarifi, S.S. Machine Learning-Based Wetland Vulnerability Assessment in the Sindh Province Ramsar Site Using Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koonce, B. EfficientNet. In Convolutional Neural Networks with Swift Tensorflow; Apress: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, R.W.; Shu, H.; Yaseen, A. Monitoring the Population Change and Urban Growth of Four Major Pakistan Cities through Spatial Analysis of Open Source Data. Ann. GIS 2023, 29, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M.; Lahn, F.; Buytaert, W.; Pebesma, E. Open and Scalable Analytics of Large Earth Observation Datasets: From Scenes to Multidimensional Arrays Using SciDB and GDAL. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 138, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilkov, A.; Krotkov, N.; Bandel, M.; Jethva, H.; Haffner, D.; Fasnacht, Z.; Torres, O.; Ahn, C.; Joiner, J. Absorbing Aerosol Effects on Hyperspectral Surface and Underwater UV Irradiances from OMI Measurements and Radiative Transfer Computations. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxevanaki, E.; Kosmopoulos, P.G.; Sotiropoulou, R.E.P.; Vigkos, S.; Kaskaoutis, D.G. Effects of Aerosols and Clouds on Solar Energy Production from Bifacial Solar Park in Kozani, NW Greece. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrashekar, G.; Sahin, F. A Survey on Feature Selection Methods. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2014, 40, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Hussain, S.; Pricope, N.G.; Arshad, S.; Tariq, A.; Feng, L.; Mubeen, M.; Aslam, R.W.; Fnais, M.S.; Li, W.; et al. Seasonal Dynamics in Land Surface Temperature in Response to Land Use Land Cover Changes Using Google Earth Engine. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 17983–17997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, L.; Aslam, R.W.; Naz, I.; Kucher, D.E.; Afzal, Z.; Raza, D.; Zulqarnain, R.M.; Said, Y. Multisensor Remote Sensing and Advanced Image Processing for Integrated Assessment of Geological Structure and Environmental Dynamics. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 16844–16857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, P.; Aslam, R.W.; Quddoos, A.; Rebouh, N.Y.; Ahmad, M.N.; Zulqarnain, R.M.; Abbas, Q.; Said, Y. Multisensor Data Fusion for Quantifying Agricultural Fire Impacts on Air Quality and Environmental Degradation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 15318–15333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Naz, I.; Quddoos, A.; Zafar, Z.; Gan, M.; Aslam, M.; Hussain, Z.K.; Soufan, W.; Almutairi, K.F. Exploring Rangeland Dynamics in Punjab, Pakistan: Integrating LULC, LST, and Remote Sensing for Ecosystem Analysis (2000–2020). Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 98, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, D.; Mohajeri, N.; Scartezzini, J.-L. A Machine Learning Methodology for Estimating Roof-Top Photovoltaic Solar Energy Potential in Switzerland. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Future Buildings & Districts Sustainability from Nano to Urban Scale, Cisbat, Lausanne, Switzerland, 9–11 September 2015; pp. 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, N.; Qin, J.; Yang, K.; Sun, J. A Simple and Efficient Algorithm to Estimate Daily Global Solar Radiation from Geostationary Satellite Data. Energy 2011, 36, 3179–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Qin, W. A Comprehensive Research on the Global All-Sky Surface Solar Radiation and Its Driving Factors during 1980–2019. Atmos. Res. 2022, 265, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notton, G.; Voyant, C.; Fouilloy, A.; Duchaud, J.L.; Nivet, M.L. Some Applications of ANN to Solar Radiation Estimation and Forecasting for Energy Applications. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Othman, A.; Ouni, A.; Besbes, M. Deep Learning-Based Estimation of PV Power Plant Potential under Climate Change: A Case Study of El Akarit, Tunisia. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2020, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Zhong, G.; Yu, H. A Review on the Attention Mechanism of Deep Learning. Neurocomputing 2021, 452, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, M.; Xie, Y.; Lopez, A.; Habte, A.; Maclaurin, G.; Shelby, J. The National Solar Radiation Data Base (NSRDB). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, B.; Luppino, L.T.; Boström, T.; Anfinsen, S.N. Random Forest Regression for Improved Mapping of Solar Irradiance at High Latitudes. Sol. Energy 2020, 198, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingye, T.; Saleem, N.; Aslam, R.W.; Sajjad, A.; Naz, I.; Tariq, A.; Alzahrani, H. Assessment of Urban Environmental Quality by Socioeconomic and Environmental Variables Using Open-Source Datasets. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 2526–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Districts | DNN-A (Wm2) | DNN-S (Wm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (nRMSE%) | MBE (nMBE%) | RMSE (nRMSE%) | MBE (nMBE%) | |

| Hannan * | 87 (34.6) | −18 (−7.0) | 122 (48.8) | 7 (2.9) |

| Caidian | 84 (33.6) | −5 (−2.1) | 97 (38.7) | 18 (7.4) |

| Dongxihu | 83 (33.5) | 0 (0.2) | 100 (40.0) | 30 (11.9) |

| Hanyang | 116 (46.3) | −57 (−22.5) | 96 (38.2) | −32 (−12.6) |

| Hongshan | 107 (40.5) | −23 (−8.8) | 88 (33.6) | −17 (−6.3) |

| Huangpi | 82 (32.1) | −14 (−5.4) | 88 (34.8) | 16 (6.2) |

| Jianghan | 148 (58.6) | 60 (23.6) | 111 (43.8) | −27 (−10.5) |

| Jiangxia | 106 (40.6) | −32 (−12.2) | 105 (40.3) | −13 (−5.1) |

| Qiaokou | 106 (42.4) | 12 (4.6) | 123 (49.3) | 48 (19.2) |

| Qingshan * | 70 (26.5) | −17 (−6.4) | 91 (34.5) | −4 (−1.6) |

| Wuchang | 106 (40.5) | −28 (−10.5) | 131 (49.8) | −46 (−17.5) |

| Xinzhou | 85 (32.1) | −38 (−14.3) | 69 (26.1) | 11 (4.0) |

| Jiangan | 101 (40.0) | −27 (−10.7) | 115 (45.8) | −1 (−0.4) |

| All | 93 (36.0) | −20 (−7.7) | 95 (37.0) | 5 (2.1) |

| Districts | DNN-S (Wm2) | DNN-A (Wm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE (nRMSE%) | MBE (nMBE%) | RMSE (nRMSE%) | MBE (nMBE%) | |

| Hannan | 72 (15.5) | 2 (0.4) | 127 (27.5) | −55 (−11.8) |

| Caidian | 64 (13.9) | 8 (1.7) | 117 (25.3) | −52 (−11.2) |

| Dongxihu | 65 (14.3) | 14 (3.1) | 118 (25.7) | −46 (−10.1) |

| Hanyang * | 59 (12.8) | −7 (−1.6) | 129 (28.2) | −60 (−13.1) |

| Hongshan | 67 (14.3) | −2 (−0.5) | 113 (24.1) | −62 (−13.1) |

| Huangpi | 78 (17.0) | 4 (0.8) | 120 (25.9) | −54 (−11.6) |

| Jianghan | 81 (17.7) | 8 (1.8) | 119 (25.9) | −74 (−16.1) |

| Jiangxia | 69 (14.8) | −11 (−2.3) | 118 (25.1) | −58 (−12.5) |

| Qiaokou | 70 (15.5) | 21 (4.6) | 124 (27.3) | −43 (−9.4) |

| Qingshan | 85 (18.2) | −19 (−4.2) | 103 (22.0) | −50 (−10.8) |

| Wuchang | 78 (16.7) | −19 (−4.1) | 143 (30.6) | −91 (−19.4) |

| Xinzhou | 77 (16.4) | −22 (−4.8) | 119 (25.4) | −66 (−14.2) |

| Jiangan | 88 (19.4) | 30 (6.7) | 99 (21.8) | −45 (−9.9) |

| All | 73 (15.6) | −3 (−0.65) | 118 (25.5) | −57 (−12.2) |

| Condition | DNN-A (W/m2) RMSE (nRMSE), MBE (nMBE) | DNN-S (W/m2) RMSE (nRMSE), MBE (nMBE) | Best Result * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clear-Sky * | 95 (28.4), −24.5 (15.5) | 89 (27.9), 0.8 (−0.4) | DNN-S (89) |

| Cloudy-Sky | 106 (42.6), −30.3 (18.3) | 103 (41.1), −3.1 (4.9) | DNN-S (103) |

| All-Sky | 95 (36.0), −19.9 (10.8) | 92 (31.4), 5.4 (0.1) | DNN-S (92) |

| Condition | DNN-A (W/m2) RMSE (nRMSE), MBE (nMBE) | DNN-S (W/m2) RMSE (nRMSE), MBE (nMBE) | Best Result * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clear-Sky | 107 (12.25), −62.3 (5.1) | 69 (10.54), −12.3 (5.0) * | DNN-S (69) |

| Cloudy-Sky | 124 (14.67), −67.5 (3.5) | 87 (16.26), −8.9 (6.5) * | DNN-S (87) |

| All-Sky | 118 (14.69), −56.6 (3.8) | 72 (15.30), −3.0 (5.9) | DNN-S (72) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hussain, Z.K.; Jiang, C.; Aslam, R.W. Multi-Sensor Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance via Perez–Ineichen and Deep Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010033

Hussain ZK, Jiang C, Aslam RW. Multi-Sensor Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance via Perez–Ineichen and Deep Neural Networks. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010033

Chicago/Turabian StyleHussain, Zeenat Khadim, Congshi Jiang, and Rana Waqar Aslam. 2026. "Multi-Sensor Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance via Perez–Ineichen and Deep Neural Networks" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010033

APA StyleHussain, Z. K., Jiang, C., & Aslam, R. W. (2026). Multi-Sensor Hybrid Modeling of Urban Solar Irradiance via Perez–Ineichen and Deep Neural Networks. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010033