MarsTerrNet: A U-Shaped Dual-Backbone Framework with Feature-Guided Loss for Martian Terrain Segmentation

Highlights

- A dual-backbone deep learning framework (MarsTerrNet) combining PRB and Swin Transformer achieves superior robustness and accuracy in Martian terrain segmentation.

- A feature-guided loss is introduced to encode geological relations and reduce confusion among visually similar terrain types.

- The proposed framework enhances geological interpretation of Martian surfaces and improves the consistency of terrain segmentation results.

- The method supports future planetary surface analysis and autonomous rover navigation on Mars.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background on Martian Terrain Perception

1.2. Mars Semantic Segmentation Methods

1.3. Hybrid CNN–Transformer Architectures for Mars Segmentation

1.4. Summary of Limitations and Our Contributions

- We design a dual-backbone architecture, named MarsTerrNet, which integrates CNN-based backbone and Swin Transformer to jointly capture fine-grained color, texture, and structural cues, while simultaneously modeling global contextual relationships.

- We propose a feature-guided loss function that explicitly encourages the model to capture structured dependencies among terrains, thereby enhancing the separability of highly correlated terrain classes and improving prediction robustness and efficiency.

- We introduce MarsTerr2024, an extended dataset to support model training. Experimental results demonstrate that our model achieves best performance on this dataset, confirming its effectiveness and reliability for Martian terrain segmentation.

2. Method

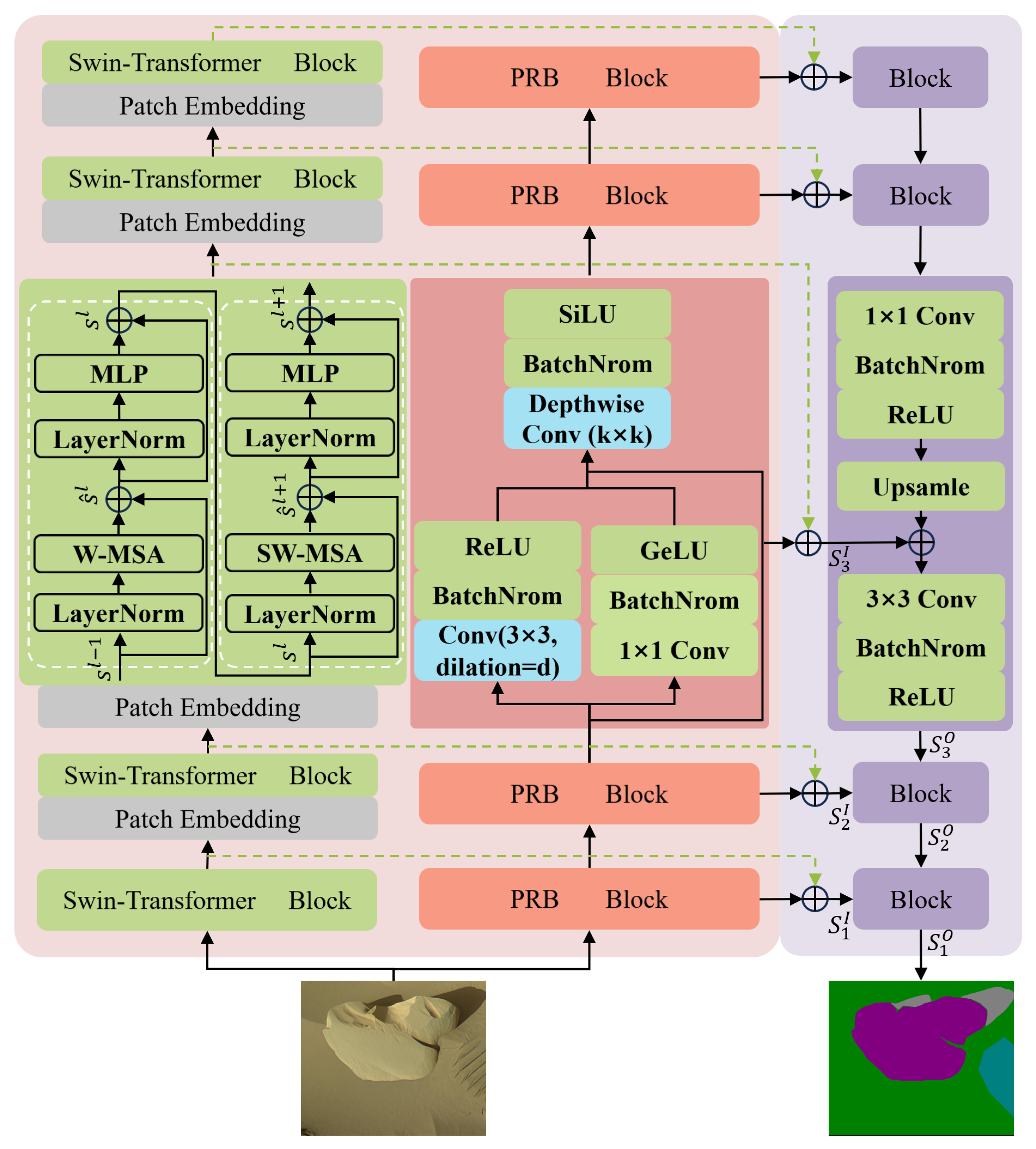

2.1. Overall Framework

2.2. CNN-Based Backbone

2.3. Swin Transformer Backbone

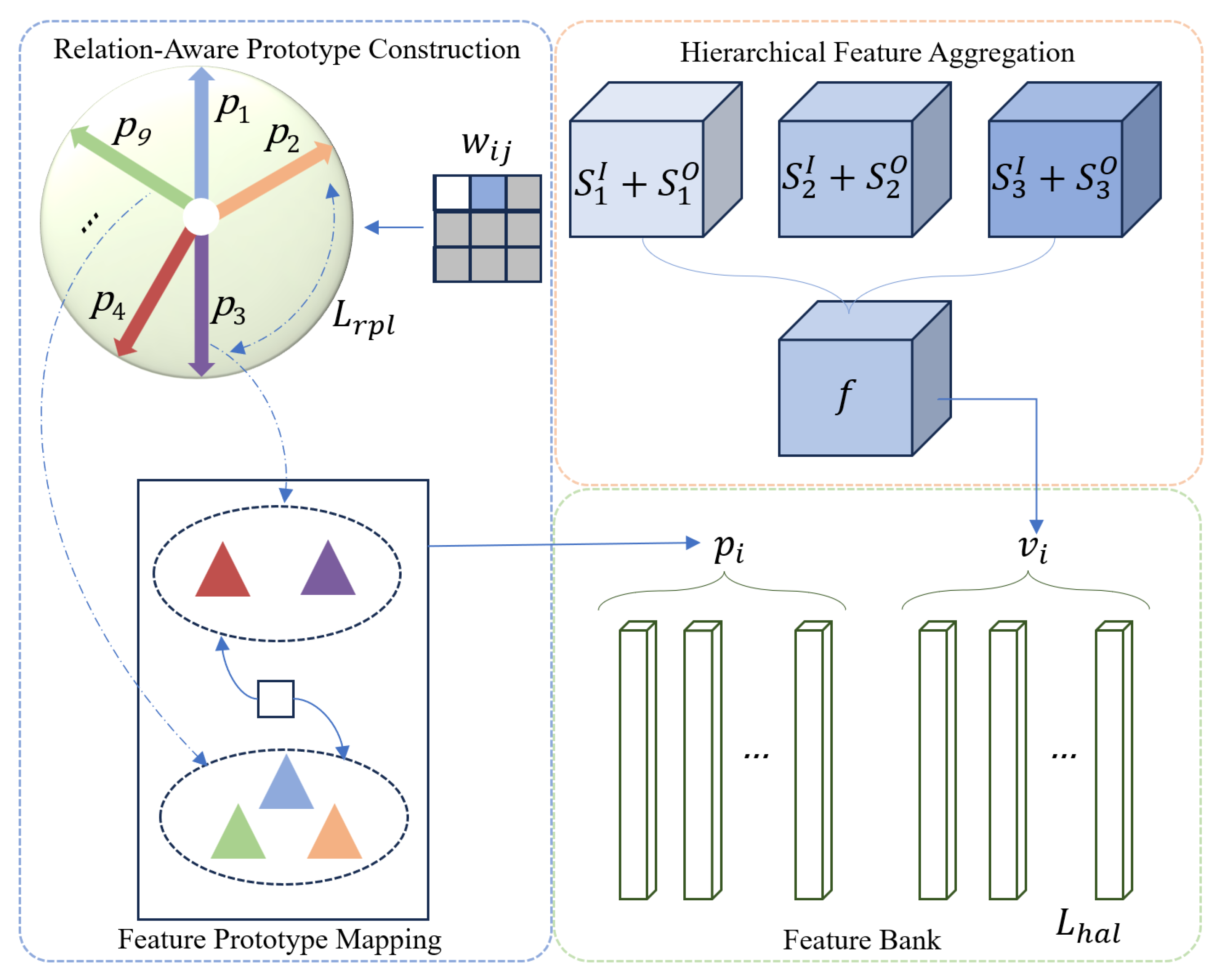

2.4. Feature-Guided Loss Function

3. Results

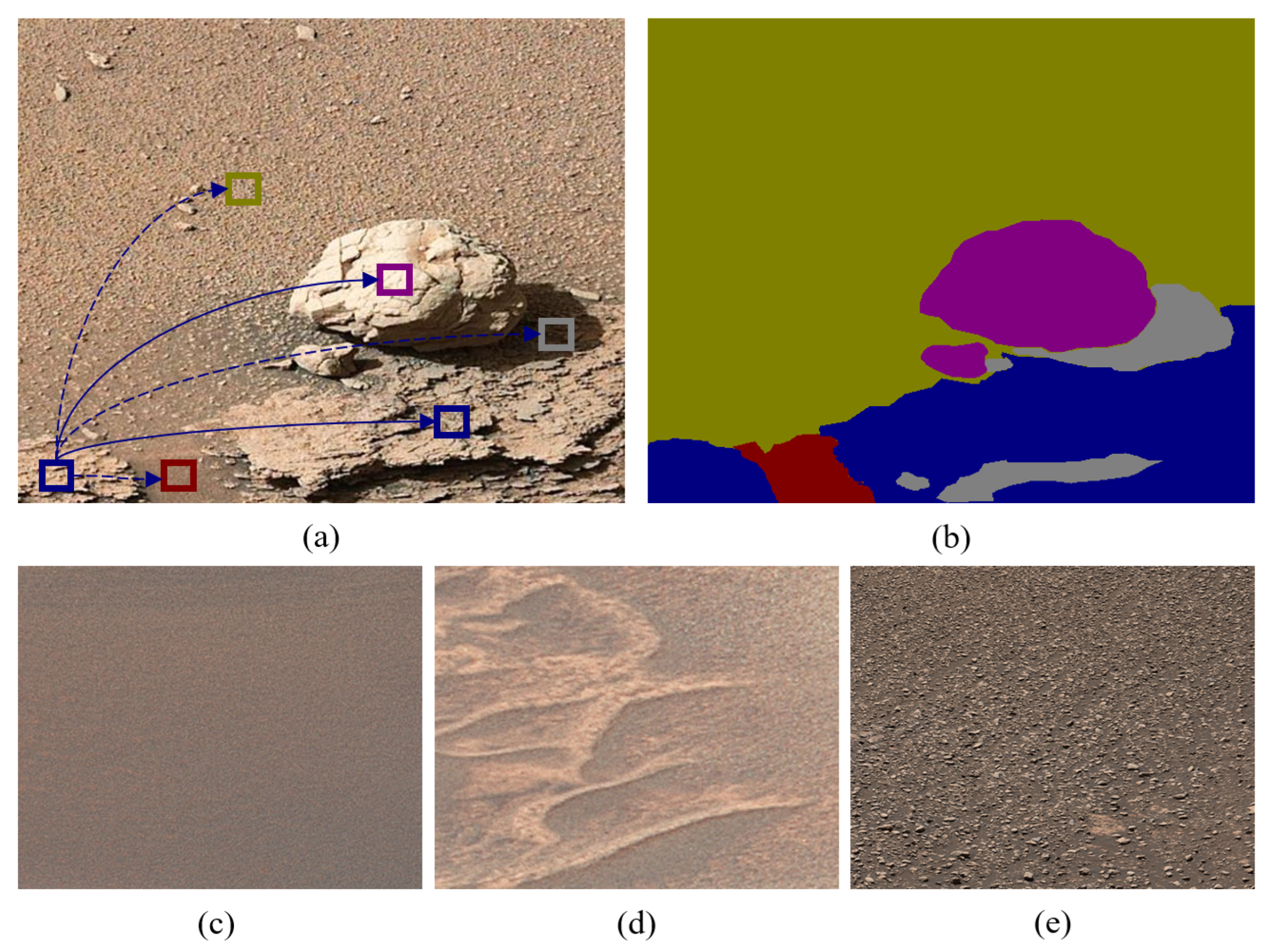

3.1. Datasets and Experimental Setting

3.2. Training Details

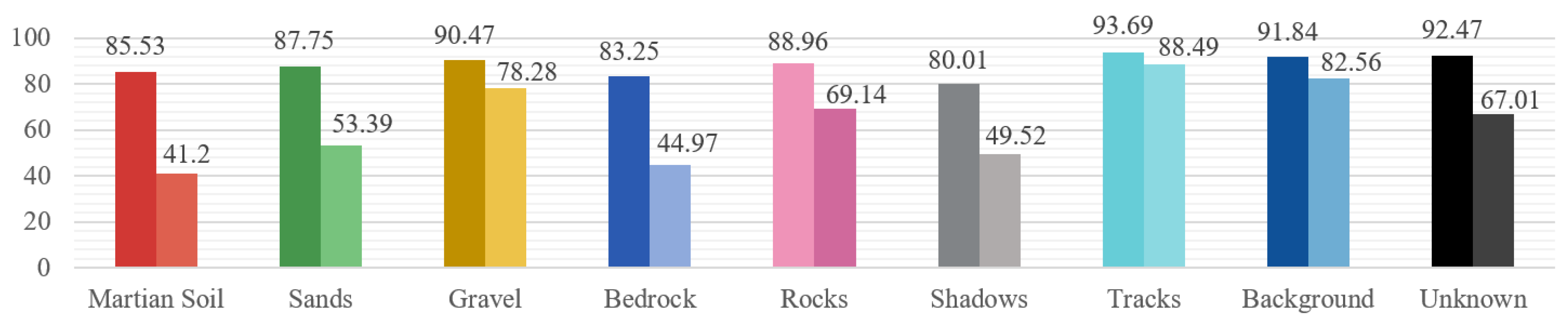

3.3. Ablation Studies

3.4. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golombek, M.P.; Trussell, A.; Williams, N.; Charalambous, C.; Abarca, H.; Warner, N.H.; Deahn, M.; Trautman, M.; Crocco, R.; Grant, J.A.; et al. Rock Size-Frequency Distributions at the InSight Landing Site, Mars. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2021EA001959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viúdez-Moreiras, D.; Newman, C.; De la Torre, M.; Martínez, G.; Guzewich, S.; Lemmon, M.; Pla-García, J.; Smith, M.; Harri, A.M.; Genzer, M.; et al. Effects of the MY34/2018 global dust storm as measured by MSL REMS in Gale crater. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2019, 124, 1899–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlmann, B.L.; Edwards, C.S. Mineralogy of the Martian surface. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2014, 42, 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siljeström, S.; Czaja, A.D.; Corpolongo, A.; Berger, E.L.; Li, A.Y.; Cardarelli, E.; Abbey, W.; Asher, S.A.; Beegle, L.W.; Benison, K.C.; et al. Evidence of Sulfate-Rich Fluid Alteration in Jezero Crater Floor, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2024, 129, e2023JE007989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burl, M.C.; Thompson, D.R.; de Granville, C.; Bornstein, B.J. Rockster: Onboard rock segmentation through edge regrouping. J. Aerosp. Inf. Syst. 2016, 13, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Z.; Ling, Z.; Cao, X.; Guo, K.; Yan, F. Autonomous Martian rock image classification based on transfer deep learning methods. Earth Sci. Inform. 2020, 13, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickel, V.T.; Conway, S.J.; Tesson, P.A.; Manconi, A.; Loew, S.; Mall, U. Deep learning-driven detection and mapping of rockfalls on Mars. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2020, 13, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bampis, L.; Gasteratos, A.; Boukas, E. CNN-based novelty detection for terrestrial and extra-terrestrial autonomous exploration. IET Cyber-Syst. Robot. 2021, 3, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3431–3440. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinarayanan, V.; Kendall, A.; Cipolla, R. Segnet: A deep convolutional encoder-decoder architecture for image segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Furlán, F.; Rubio, E.; Sossa, H.; Ponce, V. Rock detection in a Mars-like environment using a CNN. In Proceedings of the Pattern Recognition: 11th Mexican Conference, MCPR 2019, Querétaro, Mexico, 26–29 June 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. Automated crater detection on Mars using deep learning. Planet. Space Sci. 2019, 170, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogohara, K.; Gichu, R. Automated segmentation of textured dust storms on mars remote sensing images using an encoder-decoder type convolutional neural network. Comput. Geosci. 2022, 160, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 2–7 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021), Red Hook, NY, USA, 6–14 December 2021; Volume 34, pp. 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Cao, J.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Localvit: Bringing locality to vision transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.05707. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, X.; Tian, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Shen, C. Conditional positional encodings for vision transformers. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.10882. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Yao, M.; Xiao, X.; Cui, H. A hybrid attention semantic segmentation network for unstructured terrain on Mars. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 204, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wei, L.; Zheng, D.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. MarsNet: Automated rock segmentation with transformers for Tianwen-1 mission. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yao, M.; Xiao, X.; Xiong, Y. Rockformer: A u-shaped transformer network for martian rock segmentation. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yao, M.; Liu, H.; Yang, H.; Fu, Y. Marsformer: Martian rock semantic segmentation with transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 4600612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yuan, J.; Niu, X.; Zha, K.; Ma, W. RockSeg: A Novel Semantic Segmentation Network Based on a Hybrid Framework Combining a Convolutional Neural Network and Transformer for Deep Space Rock Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wan, G.; Li, W.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Cong, D.; Liu, L. EDR-TransUnet: Integrating Enhanced Dual Relation-Attention with Transformer U-Net For Multi-scale Rock Segmentation on Mars. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4601416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zheng, T.; Xue, C.; Zhou, L. SegMarsViT: Lightweight mars terrain segmentation network for autonomous driving in planetary exploration. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yao, M.; Cui, H.; Fu, Y. Light4Mars: A lightweight transformer model for semantic segmentation on unstructured environment like Mars. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 214, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zi, S.; Song, R.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Du, Q. A stepwise domain adaptive segmentation network with covariate shift alleviation for remote sensing imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Swan, R.M.; Atha, D.; Leopold, H.A.; Gildner, M.; Oij, S.; Chiu, C.; Ono, M. Ai4mars: A dataset for terrain-aware autonomous driving on mars. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1982–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fraeman, A.A.; Edgar, L.A.; Rampe, E.B.; Thompson, L.M.; Frydenvang, J.; Fedo, C.M.; Catalano, J.G.; Dietrich, W.E.; Gabriel, T.S.; Vasavada, A.; et al. Evidence for a diagenetic origin of Vera Rubin ridge, Gale crater, Mars: Summary and synthesis of Curiosity’s exploration campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2020, 125, e2020JE006527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Sutter, B.; McAdam, A.; Lewis, J.; Franz, H.; Archer, P.; Chou, L.; Eigenbrode, J.; Knudson, C.; Stern, J.; et al. Environmental changes recorded in sedimentary rocks in the clay-sulfate transition region in Gale Crater, Mars: Results from the Sample Analysis at Mars-Evolved Gas Analysis instrument onboard the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity Rover. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2024, 129, e2024JE008587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K.A.; Fox, V.K.; Bryk, A.; Dietrich, W.; Fedo, C.; Edgar, L.; Thorpe, M.T.; Williams, A.J.; Wong, G.M.; Dehouck, E.; et al. The Curiosity rover’s exploration of Glen Torridon, Gale crater, Mars: An overview of the campaign and scientific results. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2023, 128, e2022JE007185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, Y.; Lv, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Mo, L. Automated rock detection from Mars rover image via Y-shaped dual-task network with depth-aware spatial attention mechanism. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, J.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Jia, J. Pyramid scene parsing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2881–2890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Bao, Y.; Fang, Z.; Lu, H. Dual attention network for scene segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, J. Unet 3+: A full-scale connected unet for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 1055–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, B.; Wisniewski, M.; Rana, Z.A.; Zhao, Y. Rock segmentation in the navigation vision of the planetary rovers. Mathematics 2021, 9, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtehaz, N.; Rahman, M.S. MultiResUNet: Rethinking the U-Net architecture for multimodal biomedical image segmentation. Neural Netw. 2020, 121, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lu, J.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Feng, J.; Xiang, T.; Torr, P.H.; et al. Rethinking semantic segmentation from a sequence-to-sequence perspective with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 6881–6890. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. Transunet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-unet: Unet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 205–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Cao, P.; Wang, J.; Zaiane, O.R. Uctransnet: Rethinking the skip connections in u-net from a channel-wise perspective with transformer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Online, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 2441–2449. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Backbone Type | Architecture Type | Performance-Driven/ Efficiency-Oriented |

|---|---|---|---|

| HASS [20] | CNN + Attention | Sequential Hybrid | Per.-driven |

| MarsNet [21] | CNN + Transformer | Sequential Hybrid | |

| RockFormer [22] | U-Net + Transformer | Replacement Hybrid | |

| MarsFormer [23] | U-Net + Transformer | Replacement Hybrid | |

| RockSeg [24] | U-Net - Based | - | |

| EDR-TransUnet [25] | U-Net + Transformer | Sequential Hybrid | |

| SegMarsViT [26] | U-Net + Transformer | Replacement Hybrid | Eff.-oriented |

| Light4Mars [27] | U-Net + Transformer | Replacement Hybrid |

| Datasets | Year | Classes | Annotated Images | Image Size | Sulfate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mars32K | 2018 | - | 32,000 | × | |

| AI4Mars-MSL | 2021 | 4 | 17,030 | × | |

| MSL-Seg | 2022 | 9 | 4155 | × | |

| MarsScapes | 2022 | 8 | 195 | 1230~12,062 × 472~1649 | × |

| MarsData-V2 | 2023 | 2 | 8390 | × | |

| MarsTerr2024 | - | 9 | 6000 | ✓ |

| Modules | Acc | Pre | Rec | F1 | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-34 +Transformer | 73.85 | 72.47 | 71.43 | 71.95 | 58.43 |

| ResNet-34 + Swin Transformer | 75.17 | 75.24 | 73.82 | 74.52 | 60.54 |

| PRB + Transformer | 76.45 | 75.01 | 75.44 | 75.22 | 61.21 |

| PRB + Swin Transformer | 78.23 | 76.62 | 77.83 | 77.22 | 63.76 |

| + | Acc | Pre | Rec | F1 | mIoU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | 78.23 | 76.62 | 77.83 | 77.22 | 63.76 |

| ✓ | - | 82.36 | 80.51 | 81.27 | 80.90 | 65.37 |

| - | ✓ | 80.87 | 77.64 | 80.11 | 78.84 | 64.06 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 85.63 | 82.62 | 84.63 | 83.61 | 67.83 |

| Acc | Pre | Rec | F1 | mIoU | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 84.05 | 83.54 | 83.06 | 83.23 | 68.05 |

| 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 86.46 | 84.59 | 81.15 | 82.81 | 68.41 |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 88.32 | 86.91 | 85.38 | 86.14 | 71.82 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 85.93 | 84.54 | 84.35 | 84.44 | 70.68 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 83.79 | 82.44 | 83.73 | 83.08 | 68.57 |

| 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 82.56 | 80.32 | 81.29 | 80.80 | 65.49 |

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 83.12 | 81.86 | 82.95 | 82.40 | 66.32 |

| Setting | Martian Soil | Sands | Gravel | Bedrock | Rocks | Shadows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/o + | 37.69 | 50.73 | 75.91 | 39.18 | 67.93 | 45.26 |

| w/ + | 41.20 () | 53.39 () | 78.28 () | 44.97 () | 69.14 () | 49.52 () |

| Model | Acc | F1 Score | mIoU |

|---|---|---|---|

| SegFormer [17] | 67.45 () | 60.31 () | 47.16 () |

| MarsNet [21] | 75.64 () | 72.93 () | 57.41 () |

| MarsTerrNet | 78.23 () | 76.52 () | 62.87 () |

| Model | Method | Acc | mIoU | Pre | Rec | F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based | FCN [9] | 65.47 | 41.58 | 63.27 | 47.42 | 54.23 |

| PSP-Net [35] | 66.89 | 42.06 | 64.09 | 50.52 | 56.49 | |

| DeepLabv3+ [36] | 68.44 | 44.25 | 66.95 | 53.68 | 58.34 | |

| DANet [37] | 69.73 | 46.72 | 67.56 | 53.59 | 59.76 | |

| U-Net-based | U-Net [11] | 70.09 | 43.65 | 72.17 | 48.36 | 57.92 |

| U-Net3+ [38] | 72.39 | 45.26 | 71.85 | 50.34 | 59.18 | |

| NI-U-Net++ [39] | 71.67 | 50.28 | 70.82 | 55.29 | 62.08 | |

| MultiResUnet [40] | 73.54 | 48.39 | 76.77 | 53.79 | 63.26 | |

| Transformer-based | SETR [41] | 74.53 | 52.25 | 73.21 | 63.29 | 67.87 |

| SegFormer [17] | 76.42 | 56.36 | 75.69 | 66.59 | 70.89 | |

| U-shaped Transformer-based | TransUnet [42] | 78.44 | 56.19 | 76.25 | 70.53 | 73.28 |

| Swin-Unet [43] | 79.05 | 58.74 | 77.89 | 74.53 | 76.18 | |

| SwinUpperNet [29] | 80.12 | 61.86 | 79.38 | 78.11 | 78.75 | |

| UCT-TransNet [44] | 60.68 | 62.29 | 80.53 | 81.95 | 81.20 | |

| MarsNet [21] | 81.83 | 63.08 | 83.17 | 77.36 | 80.12 | |

| MarsTerrNet | 84.05 | 66.32 | 81.86 | 82.95 | 82.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Zhou, K.; Wang, J.; Bi, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W.; Qu, G.; Li, C.; Qiu, H. MarsTerrNet: A U-Shaped Dual-Backbone Framework with Feature-Guided Loss for Martian Terrain Segmentation. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010035

Wang R, Sun J, Zhou K, Wang J, Bi J, Zhang Q, Wang W, Qu G, Li C, Qiu H. MarsTerrNet: A U-Shaped Dual-Backbone Framework with Feature-Guided Loss for Martian Terrain Segmentation. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Rui, Jimin Sun, Kefa Zhou, Jinlin Wang, Jiantao Bi, Qing Zhang, Wei Wang, Guangjun Qu, Chao Li, and Heshun Qiu. 2026. "MarsTerrNet: A U-Shaped Dual-Backbone Framework with Feature-Guided Loss for Martian Terrain Segmentation" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010035

APA StyleWang, R., Sun, J., Zhou, K., Wang, J., Bi, J., Zhang, Q., Wang, W., Qu, G., Li, C., & Qiu, H. (2026). MarsTerrNet: A U-Shaped Dual-Backbone Framework with Feature-Guided Loss for Martian Terrain Segmentation. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010035