Post-Fire Restauration in Mediterranean Watersheds: Coupling WiMMed Modeling with LiDAR–Landsat Vegetation Recovery

Highlights

- Hydrological model–LiDAR integration captured post-fire hydrology changes.

- Runoff increased after wildfires but decreased as vegetation recovered.

- A Priority Post-Fire Restoration Index (PPRI) is proposed.

- Remote sensing–hydrological model integration improved pre- and post-fire simulations.

- The PPRI helps to optimize post-fire restoration interventions.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Vegetation Data

2.3. Remote Sensing Data Acquisition and Processing

2.4. Trends in Canopy Height and Cover Recovery After Fire

2.5. Hydrological Model

2.6. Long-Term Post-Fire Restoration Priorities

| Priority Post-fire Restoration Index = α × Runoff + β × flow accumulation + µ × distance to drainage network+ γ × slope + δ × erodibility factor k + ε × lithology + η × Lidar | (1) |

3. Results

3.1. Post-Fire Hydrological Processes

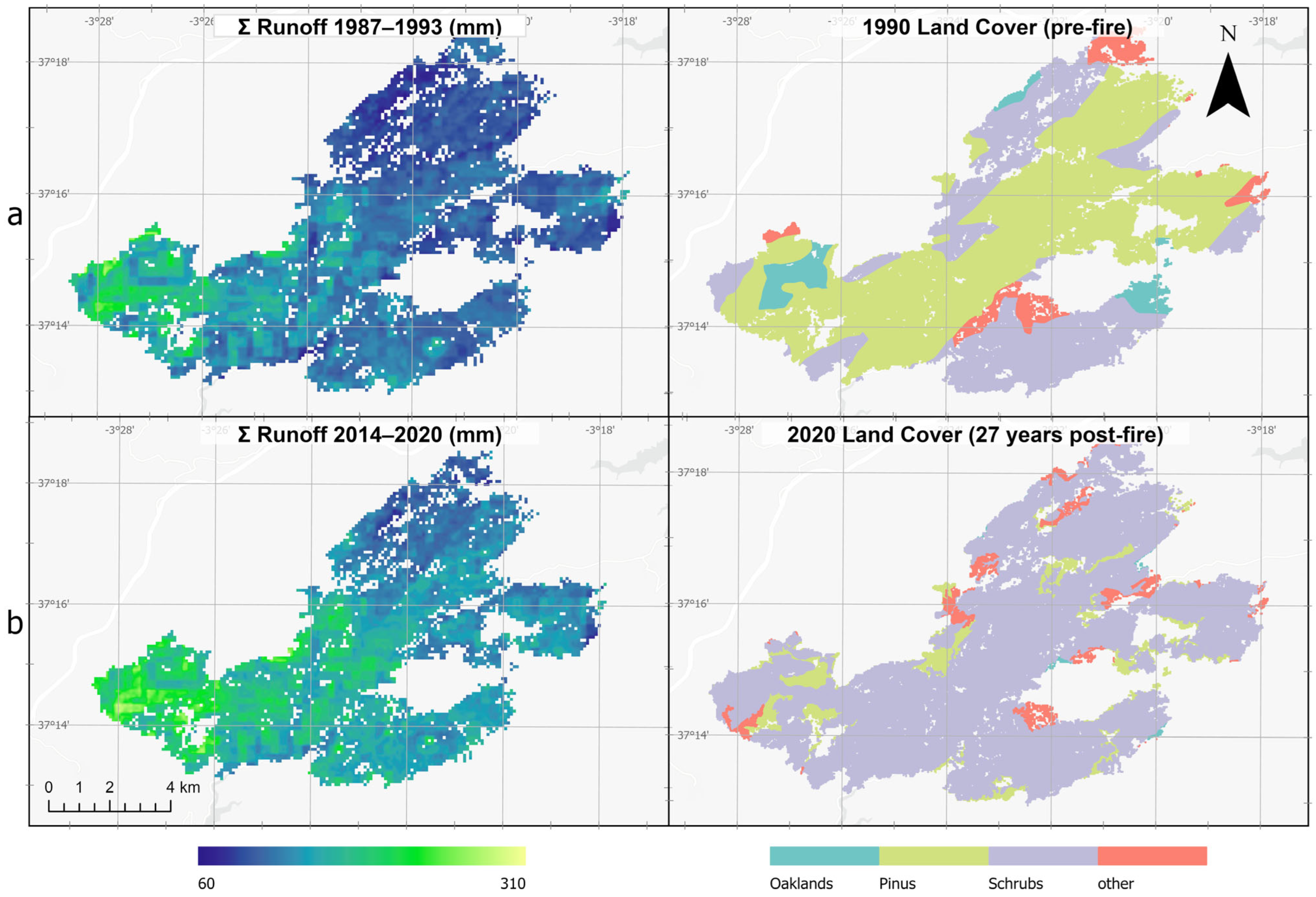

3.2. Post-Fire Runoff Map

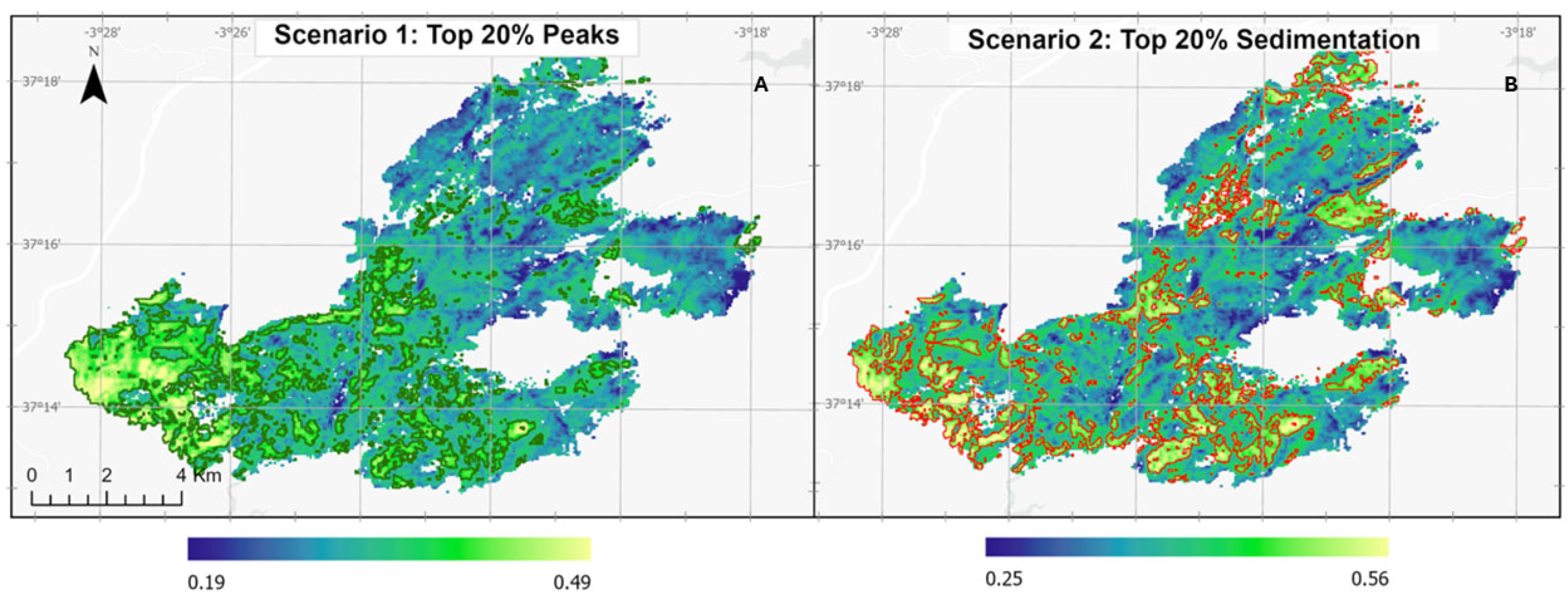

3.3. Priority Post-Fire Restoration Index

4. Discussion

4.1. Hydrological Responses Under Post-Fire Conditions

4.2. Integration of Remote Sensing and Field Data for Improved Simulations

4.3. Identification of Priority Areas for Restoration and Management

4.4. Broader Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WiMMed | Watershed Integrated Management in Mediterranean Environments |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| PPRI | Priority Post-Fire Restoration Index |

References

- Mansoor, S.; Farooq, I.; Kachroo, M.; Mahmoud, A.; Fawzy, M.; Popescu, S.; Ahmad, P. Elevation in wildfire frequencies with respect to the climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazeni, S.; Cerdà, A. The impacts of forest fires on watershed hydrological response. A review. Trees For. People 2024, 18, 100707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Leal, M.; Bergonse, R.; Canadas, M.J.; Novais, A.; Oliveira, S.; Santos, J.L. Recent trends in fire regimes and associated territorial features in a fire-prone Mediterranean region. Fire 2023, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pelayo, O.; Prats, S.A.; van den Elsen, E.; Malvar, M.C.; Ritsema, C.; Bautista, S.; Keizer, J.J. The effects of wildfire frequency on post-fire soil surface water dynamics. Eur. J. For. Res. 2024, 143, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ahn, S.; Kim, T.; Im, S. Post-fire impacts of vegetation burning on soil properties and water repellency in a pine forest, South Korea. Forests 2021, 12, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.; Sheridan, G.; Lane, P.; Nyman, P.; Haydon, S. Wildfire effects on water quality in forest catchments: A review with implications for water supply. J. Hydrol. 2011, 396, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.; Bendick, R.; Hyde, K.; Gabet, E. Frequency–magnitude distribution of debris flows compiled from global data, and comparison with post-fire debris flows in the western US. Geomorphology 2013, 191, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana-Soto, A.; García, M.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J. Assessing post-fire forest structure recovery by combining LiDAR data and Landsat time series in Mediterranean pine forests. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf 2022, 108, 102754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Pereira, E.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M. Post-fire regeneration dynamics of heterogeneous Mediterranean ecosystems using Landsat and ALS data. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 1001, 180435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarley, T.R.; Kolden, C.A.; Vaillant, N.; Hudak, A.; Smith, A.; Wing, B.; Kreitler, J. Multi-temporal LiDAR and Landsat quantification of fire-induced changes to forest structure. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 191, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemeyer, R.; Bladon, K.; Woodsmith, R.D. Long-term hydrologic recovery after wildfire and post-fire forest management in the interior Pacific Northwest. Hydrol. Process. 2020, 34, 1182–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, E.W.; Wagenbrenner, J.W.; Zhang, L. Wildfire and hydrological processes. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36, e14640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J.; Millares Valenzuela, A.; Moreno Llorca, R. Outputs of the WiMMed Hydrological Model for Sierra Nevada (Spain). 2023. Available online: https://produccioncientifica.ugr.es/documentos/668fc432b9e7c03b01bd615b?lang=en (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Egüen, M.; Aguilar, C.; Herrero, J.; Millares, A.; Polo, M.J. On the influence of cell size in physically based distributed hydrological modelling to assess extreme values in water resource planning. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1573–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebel, B.A.; Shephard, Z.M.; Walvoord, M.A.; Murphy, S.F.; Partridge, T.F.; Perkins, K.S. Modeling post-wildfire hydrologic response: Review and future directions for applications of physically based distributed simulation. Earth’s Future 2023, 11, e2022EF003038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, C.H.; Benson, N.C. Landscape assessment (LA). In FIREMON: Fire Effects Monitoring and Inventory System; Lutes, D.C., Keane, R.E., Caratti, J.F., Key, C.H., Benson, N.C., Sutherland, S., Gangi, L.J., Eds.; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2006; Volume 164, p. LA-1-55. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Clemente, R.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Gitas, I.Z. Monitoring post-fire regeneration in Mediterranean ecosystems by employing multitemporal satellite imagery. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andalucía, J. Sistema de Información Sobre el Patrimonio Natural de Andalucía. 2021. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/portal/landing-page-%C3%ADndice/-/asset_publisher/zX2ouZa4r1Rf/content/sistema-de-informaci-c3-b3n-sobre-el-patrimonio-natural-de-andaluc-c3-ada-sipna-/20151 (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- PNOA. Available online: https://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/home (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Isenburg, M. LAStools; Rapidlasso GmbH: Gilching, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, J.; Auty, D.; Coops, N.; Tompalski, P.; Goodbody, T.; Meador, A.; Achim, A. lidR: An R package for analysis of Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 251, 112061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schowengerdt, R.A. Techniques for Image Processing and Classifications in Remote Sensing; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soenen, S.A.; Peddle, D.R.; Coburn, C.A. SCS+ C: A modified sun-canopy-sensor topographic correction in forested terrain. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 2148–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K.J.; Kirkby, M.J. A physically based, variable contributing area model of basin hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1979, 24, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, L.N.; Lee, G. Investigating the Relationship Between Topographic Variables and Wildfire Burn Severity. Geographies 2025, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REDIAM. Available online: https://portalrediam.cica.es/caracterizacion_vegetacion/sipna.html (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Moreno, I.; Millares, A.; Herrero, J.; Losada, M.A.; Aguilar, C.; Polo, M.J. WiM-Med, un modelo de gestión hidrológica a escala de cuenca. IV Congreso Andaluz de Desarrollo Sostenible/VIII Congreso Andaluz de Ciencias Ambientales. (Calibrated for the Guadalfeo basin, Andalusia). 2009. Available online: https://digibug.ugr.es/bitstream/handle/10481/62222/Moreno_2009_Ambientalia.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Inbar, A.; Lado, M.; Sternberg, M.; Tenau, H.; Ben-Hur, M. Forest fire effects on soil chemical and physicochemical properties, infiltration, runoff, and erosion in a semiarid Mediterranean region. Geoderma 2014, 221, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.L. Decision making with the analytic hierarchy process. Int. J. Serv. Sci. 2008, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, W.; Qian, M.; Zha, E.; Shi, X. A Multi-Objective Framework for Regional Ecological Planning: Restoration Prioritization Analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3670–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, P.K.; Campagne, C.S.; Ganteaume, A. Post-fire Recovery Dynamics and Resilience of Ecosystem Services Capacity in Mediterranean-Type Ecosystems. Ecosystems 2024, 27, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermitão, T.; Gouveia, C.M.; Bastos, A.; Russo, A.C. Recovery following recurrent fires across Mediterranean ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, P.; Cerdà, A.; Úbeda, X.; Mataix-Solera, J.; Rein, G. (Eds.); Fire Effects on Soil Properties; CSIRO Publishing: Camberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, A.G.; Bautista, S.; Llovet, J.; Bellot, J. Post-fire hydrological and erosional responses of a Mediterranean landscpe: Seven years of catchment-scale dynamics. Catena 2007, 71, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, R.; Rulli, M.C.; Bocchiola, D. Transient catchment hydrology after wildfires in a Mediterranean basin: Runoff, sediment and woody debris. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakesby, R.A.; Doerr, S.H. Wildfire as a hydrological and geomorphological agent. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2006, 74, 269–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Doerr, S.H. The effect of ash and needle cover on surface runoff and erosion in the immediate post-fire period. Catena 2008, 74, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, N.R.; Coops, N.C.; Culvenor, D.S. Development of a simulation model to predict LiDAR interception in forested environments. Remote Sens. Environ. 2007, 111, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Dunkerley, D.; Lopez-Vicente, M.; Shi, Z.H.; Wu, G.L. Trade-off between surface runoff and soil erosion during the implementation of ecological restoration programs in semiarid regions: A meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 712, 136477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Singer, M.J.; Dahlgren, R.A.; Tate, K.W. Hydrology in a California oak woodland watershed: A 17-year study. J. Hydrol. 2000, 240, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortesa, J.; Latron, J.; García-Comendador, J.; Company, J.; Estrany, J. Runoff and soil moisture as driving factors in suspended sediment transport of a small mid-mountain Mediterranean catchment. Geomorphology 2020, 368, 107349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, G.; Alamanos, A.; Maris, F. Evaluating post-fire erosion and flood protection techniques: A narrative review of applications. GeoHazards 2023, 4, 380–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Borja, M.E. Efficiency of postfire hillslope management strategies: Gaps of knowledge. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 21, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Shao, Q.; Fan, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, J.; He, J. Assessment of restoration degree and restoration potential of key ecosystem-regulating services in the three-river headwaters region based on vegetation coverage. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, J.; Millares, A.; Aguilar, C.; Egüen, M.; Losada, M.A. Coupling spatial and time scales in the hydrological modelling of mediterranean regions: WiMMed. In CUNY Academic Works, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Hydroinformatics HIC 2014, New York, NY, 17–21 August 2014; City University of New York (CUNY): New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- ITGE-Junta de Andalucía. Atlas Hidrogeológico de Andalucía; IGME: Madrid, Spain, 1998; 216p, ISBN 84-7840-351-5. Available online: https://web.igme.es/actividadesigme/lineas/HidroyCA/publica/libros1_HR/libro110/lib110.htm (accessed on 11 January 2025).

- Herrero, J.; Aguilar, C.; Millares, A.; Polo, M.J. WiMMed MANUAL DE USUARIO V 2.0; Grupo de Dinámica Fluvial e Hidrología, Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, Spain; Grupo de Dinámica de Flujos Ambientales Centro Andaluz de Medio Ambiente (CEAMA), Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Runoff | Sediments |

|---|---|---|

| Runoff (mm) | 0.30 | 0.22 |

| Flow accumulation (mm) | 0.19 | 0.18 |

| Distance to drainage network (m) | 0.11 | 0.14 |

| Slope (%) | 0.15 | 0.17 |

| Lithology | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| Erodibility factor K | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| LiDAR | 0.10 | 0.03 |

| CR | 0.002 | 0.015 |

| Category | SED | PEAKS |

|---|---|---|

| High | 682.61 (10.06) | 308.45 (4.55) |

| Low | 1376.48 (20.29) | 1559.37 (22.98) |

| Middle | 4647.88 (68.50) | 4860.74 (71.64) |

| Very High | 24.93 (0.37) | 12.96 (0.19) |

| Very Low | 52.92 (0.78) | 43.29 (0.64) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Velasco Pereira, E.A.; Navarro Cerrillo, R.M. Post-Fire Restauration in Mediterranean Watersheds: Coupling WiMMed Modeling with LiDAR–Landsat Vegetation Recovery. Remote Sens. 2026, 18, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010026

Velasco Pereira EA, Navarro Cerrillo RM. Post-Fire Restauration in Mediterranean Watersheds: Coupling WiMMed Modeling with LiDAR–Landsat Vegetation Recovery. Remote Sensing. 2026; 18(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelasco Pereira, Edward A., and Rafael Mª Navarro Cerrillo. 2026. "Post-Fire Restauration in Mediterranean Watersheds: Coupling WiMMed Modeling with LiDAR–Landsat Vegetation Recovery" Remote Sensing 18, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010026

APA StyleVelasco Pereira, E. A., & Navarro Cerrillo, R. M. (2026). Post-Fire Restauration in Mediterranean Watersheds: Coupling WiMMed Modeling with LiDAR–Landsat Vegetation Recovery. Remote Sensing, 18(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs18010026